1. Introduction

Swales [

1] stated that the abstract is both a summary and a ‘purified’ reflection of the entire article, while Bhatia refers to the informative function of abstracts, claiming that they present “a faithful and accurate summary, which is representative of the whole article” [

2] (p. 82). However, in addition to being informative, abstracts have a significant role in promoting research reports. Hyland [

3], for example, maintains that it provides a decision making point for readers to judge whether the entire article merits further attention or not. Many academic writers therefore try to “persuade their readers to read the whole article by their effective selection of rhetorical features” [

4] (p. 163). Martı́n-Martı́n notes that “abstracts constitute, after the paper’s title, the reader’s first encounter with the text”, [

5] (p. 5) pointing out that “there are few scholarly journals that do not require an abstract to be sent together with the original paper” [

6] (p. 26). In general, unlike their accompanying articles, abstracts are freely available online, while many articles written in languages other than English also have English abstracts. Thus, being able to compose effective abstracts is critical for academic writers, and studying the language of abstracts is of significant value.

The literature also reveals that novice writers still have difficulty constructing well-structured abstracts that are appropriate to the norms set by their scientific community. For instance, Busch-Lauer found some linguistic and structural inadequacies in abstracts by Germans writing in English, which “may hamper the general readability for the scientific community” [

7] (p. 769). Similarly, Ren and Li reported student writers’ “incomplete appropriation to disciplinary practices” [

4] (p. 165). Some student writers even had a “limitation” in their abstracts, which can be viewed as a sign of their insecurity or weakness as novice writers. Therefore, just like other sections of a research paper, studies regarding abstracts are required to raise novice writers’ awareness by providing them with more rhetorical knowledge and guidelines to design better structured abstracts for their research articles.

One conventional method for examining language use, rhetoric, and text organization is move analysis. Moves are categories of functional roles in communication—in the present case, academic writing. For example, when writers express their ideas about what is missing in the previous literature, the purpose is probably to show that their study is going to fill this gap. Thus, we can identify these instances and mark them as

gap-move. Previous studies have designed different move schemes for different sections of research articles in different fields. These schemes are composed of a number of moves and submoves (or

steps). To illustrate, Stoller and Robinson [

8] identified three major moves in methodology sections of research articles in the field of chemistry; namely,

Move 1: Describe materials;

Move 2: Describe experimental methods; and

Move 3: Describe numerical methods. In addition to these major moves, they included two submoves for Move 2, namely

procedures and

instrumentation. These five categories were enough to tag the methodology sections of their sample of articles and analyze their rhetorical structures (for an informative summary on move analysis, see also Cortes [

9], p. 35). Once a piece of text is tagged for moves, its rhetorical structure can be described, and comparisons with other texts can be made.

Previous studies have analyzed moves from four perspectives:

range,

amount,

organization, and

linguistic features. The majority of move-analysis studies have explored the issue of

range (essentiality), or how necessary a move is. For example, they ask how many introduction sections out of one hundred contain background information about the study (

background-move), or how many abstracts out of one hundred present the results (

results-move). An arbitrary cut-off point is set to assign a category for each move; for example, if a move occurs in 60% or more of the particular section in different articles, then it can be labeled

conventional, or if less,

optional [

10]. At the time of the present paper, eight studies had investigated the issue of essentiality in applied linguistics (AL) abstracts, using the same or comparable frameworks. Thus, in the present paper, we tabulate the results from these previous studies alongside with our findings to present the general picture.

Some studies also focused on

amount (

length) of moves in sections, for example, asking what percentage of texts on average is allocated for discussing the weaknesses of the study (

limitation-move). The total can be calculated based on frequency counts of move-tags or the number of words within a move-tag. For example, Ren and Li [

4] argued that the importance attached to a move is concomitant with the length devoted to it. One of their findings was that abstracts written by students in AL allotted more words to the introduction move, whereas abstracts from published research articles had more words in the results move. They interpreted this difference as indicating that deficiencies in student studies created insecurity about their results. However, most previous studies have ignored this important variable of

amount (length) for moves. The present study also strives to fill this gap.

Because almost all studies emphasize a connection between move analyses and materials development for teaching,

organization of move categories in a paper or section, how moves are sequenced, is also a critical part of move-analysis approaches. Salager-Meyer [

11] (as cited in Hyland [

12]) asserts that a well-structured abstract should involve all four structural units (

introduction-methods-results-conclusions) in a linear order. But is this really so? Do they follow an order that is promoted by teaching materials or expected by schemes for move analyses? Where do writers locate suggestions for future studies in their discussions (

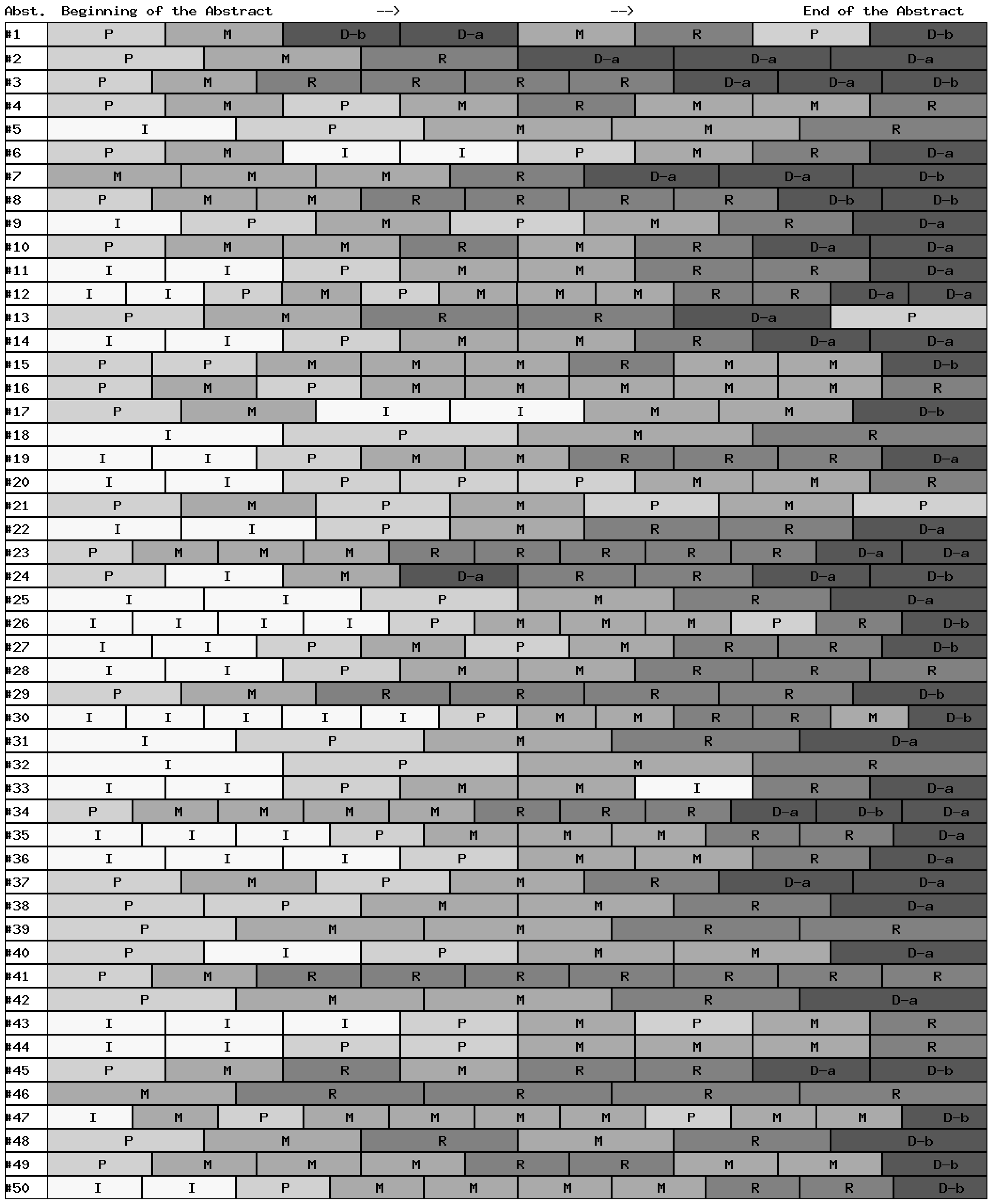

future studies move)? Previous studies presented these organizational patterns in a non-systematic way, such as discussions of several patterns that are observed most frequently. The present study attempts to offer an innovative visual chart that visualizes move organization in the whole sample of 50 abstracts, as presented in the third section below. In addition, we undertake more systematic counts of move patterns.

Lastly, again for the ultimate reason of developing teaching materials, many previous studies also examined certain lexical features. What kinds of grammar structures, vocabulary, tense, modals, formulaic expressions and similar other language features are used to realize these moves? For example, what kinds of verbs or terms do authors use when describing the statistics used in the study (

numerical methods move)? Which tenses do authors use when describing procedures in methods sections (

procedure-move)? To illustrate, Hyland and Tse, comparing abstracts written by novice and expert writers for use of the evaluative

that in abstracts, showed that both novice and expert writers tend to use the

that construction quite frequently “to mark their main argument, to summarize the purposes of the research and to express a stance on the reliability of the information presented” [

13] (p. 137). However, analyzing linguistic features within each move category is beyond the scope of the present study.

In addition to descriptions, comparisons of the move features described above can be made between move types, native and non-native English (or novice and expert) users, between different languages, across disciplines, and different points in time. Studies comparing novice and expert writers include Amnuai and Wannaruk [

14], Busch-Lauer [

7], Ren and Li [

4], Samar, Talebzadeh, Kiany, and Akbari [

15], and Tseng [

16]. To illustrate, using the framework of Hyland [

12], Ren and Li [

4] compared the essentiality of rhetorical moves in abstracts written by expert and novice writers, and found that while student writers include all five moves in their abstracts, experts often included only three of them, namely

purpose-method-results, ignoring the

introduction and

discussion moves. They concluded that experts do this in order to emphasize the persuasive, rather than informative role of abstracts. The present study, however, does not distinguish between native and non-native writers, and accepts all writers as

expert users since they are published in the

English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Journal.

Other studies, such as Alharbi and Swales [

17] and Martı́n-Martı́n [

6], have focused on comparing text organization in English and other languages. For example, Martı́n-Martı́n [

6] compared social sciences abstracts in English and Spanish. Based on his four-move scheme, he found that 86% of articles in English involved the results move but only 41% in Spanish. In the present study, however, we only focused on AL abstracts in English.

Comparisons have also been made across disciplines, for example Ghasemi and Alavi [

18], Hyland [

12], Li and Pramoolsook [

19], Pho [

20], and Saeeaw and Tangkiengsirisin [

21]. Min [

22] compared the verb tenses of humanities and social sciences (HSS), and natural sciences and technology (NST) research abstracts. The results indicated that tense choices were not significantly different, with the present tense being most prevalent. In addition, both disciplines showed a clear preference for the present perfect tense when referring to more than a single study and for the past tense when expressing reference to the author’s own study. As mentioned earlier, the present study focuses only on abstracts from AL research articles.

Some studies have investigated whether text organization changes diachronically, such as Hyland [

12], Hyland [

3], Okamura and Shaw [

23], and the present paper. While the abstracts we selected do not represent diachronic data, through comparisons with previous studies, there is a diachronic dimension regarding

essentiality.

There has been a considerable amount of research on language use in AL abstracts (e.g., [

4,

12,

16,

20,

21,

24,

25]). However, no study has aggregated findings from previous studies into a readable table. The present study does this in the third section below.

The journal English for Specific Purposes (ESP) is highly regarded in the field of AL, providing a rich source of data for move analysis studies, which may mean that its writers are more conscious about the rhetorical organization of their articles. The present paper reports a study of the distribution and arrangement of move patterns in ESP journal abstracts published between 2011 and 2013. The current study sought to answer the following research questions:

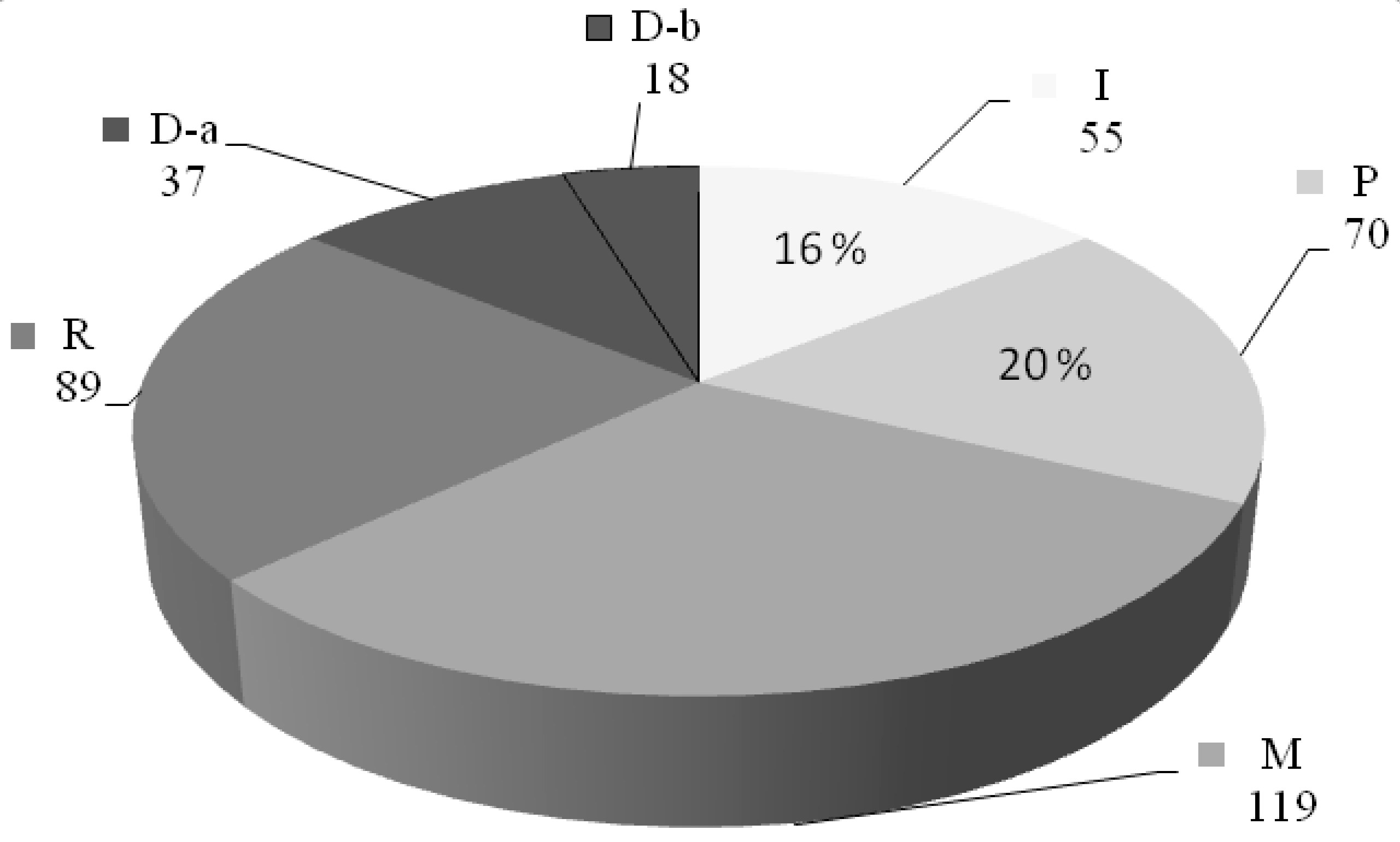

What is the range of the moves in AL abstracts? That is, what percentage of abstracts contain the target move (essentiality of a move)?

What is the amount of moves with respect to other moves in AL abstracts? That is, how much space is allotted for each move in the abstract (length; percentage of data for each move-tag)?

How are moves organized in AL abstracts? That is, how well do moves follow the typical order of introduction-methods-results-discussion (sequence, linearity)? What are the frequent move sequences (patterns)?

4. Conclusions

Although this study examined the move structures of 50 abstracts from a single AL journal, ESP, results were consistent with previous studies using data from a variety of AL journals. Thus, despite this relevant limitation in journal variety, our data seems representative of the language of AL abstracts. While space constraints prevented us from discussing the key linguistic structures within these moves, we believe linguistic realizations of moves deserve a separate detailed discussion using a much larger corpus than the ones in the present and previous studies.

The findings of the present and previous studies show that authors discuss results, purpose, and methodology in their abstracts more than implications of the findings or background information. Authors are well aware of the fact that they need to use the allowed space economically. Background information about the topic is the first to be omitted by writers in AL, and thus it seems to be the only move in the optional category, being disregarded in more than half of the sampled abstracts. Overall, purpose, methodology, results, and implications of results are conventional, appearing in most AL abstracts. However, many writers avoid an informative discussion of their results. This frugality in interpreting the outcome of their studies not only allows them to save space but may also enable them to stimulate curiosity in the reader.

Writers in AL follow the typical introduction-(purpose)-methods-results-discussion order but with many deviations. For example, although the background move occurs in less than half of the abstracts, it is the most frequent move in the first sentence. Similarly, while closing the abstracts, writers mostly preferred discussing the implications of their findings. Thus, more than half of the abstracts follow a linear order, even if there are omissions of moves, while others do not follow the order due to iteration or deviant locations of moves.

AL writers often combine the methodology with the purpose or results of their study within the same sentence. It is no surprise that the methodology move also takes the largest space in abstracts. The strategy of combining moves in a single sentence probably prevents choppiness and helps force more information into an inherently limited space.

As noted, the findings of the present study are consistent with the majority of previous studies in this line of inquiry. These congruous findings of move organizations and linguistic realizations could be of great use to teach novice writers how to write an abstract. Future studies should make this connection between the findings of move analyses and teaching materials for academic writing. Consequently, studying the effects of data-informed teaching materials on novice writers is another important research avenue. To this end, a larger corpus of move-tagged abstracts seems necessary to understand linguistic structures related to moves in abstracts that are sufficient to create teaching materials. However, move annotation is a labor-intensive undertaking so automatizing it is vital. One such attempt is a move-tagging software program named AntMover [

27] (Version 1.0.0, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan), although it is yet to be effectively utilized in move analyses; i.e., no studies cited in this paper used it. For such an automatic move-coding program to be realized, it is vital to compile hand-coded training materials with a standardized scheme, which requires co-operation between researchers doing hand-analysis and software developers.