1. Introduction

The dominance of English in the publishing world has had a decisive impact on the dissemination of information and innovation across cultures, with the resulting risk of a standardization of scientific conceptualization and domain loss, where an increasing number of fields can no longer be expressed in any language other than English. Awareness of this risk has developed lately in the field of academic discourse analysis [

1,

2,

3] and various leads have been offered to counter the exclusion of non-English speakers, who tend to be considered as “peripheral writers” [

4,

5]. However, the dominance of English does not only impact scientific and academic discourse, but also the whole range of professional and technical texts grouped under specialized discourse.

This paper advocates engaging in the practice of dynamic translation [

6] to keep non-English specialized language alive. In a dynamic perspective, translation transfers information and knowledge from a source to a target culture so as to make it understandable by the reader while respecting its original specificity. Based on the intercultural and interlinguistic transfer of specialized metaphor, it is argued that a reflective practice of translation offers an effective means of identifying the various cultural voices in a field of research. The evaluation of alternatives which underpin a translation choice is used as a magnifying glass for the observation of cultural gaps or divides within globalized fields of knowledge.

Essays written by master’s students

1 on specialized translation, commenting on their own translations, provide rich material to identify examples of conflicting views of the world in emerging and controversial fields. The trainee translators combine contextual knowledge and corpus observation to offer solutions to transfer the meaning of specialized concepts. Their commentaries open perspectives for understanding ethical dilemmas which underpin their translation choices, especially lexical choices, and the conditions under which a reflective practice of translation helps to develop writers’ awareness of the consequences of their choices [

7] (p. 141). Below, we will show, using two specific examples, how the transfer of metaphor from one culture to another and the resulting variations in both words and meaning reveal conflicting epistemological patterns which characterize the field under study.

Section 1 introduces the proposal of dynamic translation as a practice to keep non-English specialized languages alive in the context of English dominance.

Section 2 sets the scene by discussing the specific impact that domain loss can have on specialized varieties of language, the potential role of translation on domain loss and the issue of metaphor. It is argued that the practice and analysis of translation provide an appropriate approach for a better understanding of languages for specific purposes (LSP) and for raising the awareness of domain loss and epistemicide. In

Section 3, students’ reports on their translation choices provide material for two case studies of the transfer of specialized metaphors and the impact of this transfer.

Section 4 shows to what extent the study of the translation process leads to an understanding of domain loss and thereby gives the means to counteract it.

3. Two Case Studies: “Shadow Banking” and “Human Branding”

Students’ reports on their translation and the related terminological exploration provide useful material to better understand the impact of a translation decision when dealing with metaphor’s intercultural transfer. In this specialized translation master’s program, reports are written as a part of the master’s dissertation in translation. They describe and comment on a year-long research process. At the beginning of the year, the students choose a specialized field. They explore common issues and “situated activities” which define the discourse community [

13], by relying on the compilation of a comparable corpus of the domain’s textual productions. Using this corpus and with the help of experts in the field, they select the most representative terms and study, intra and interlinguistically, their specific meaning as well as their contextual environment. The collected data are entered in the Artes terminology database [

26]. A tree diagram is built to represent the semantic links connecting the node terms. This conceptual and linguistic exploration provides the information required for the translation of a specialized document in the chosen field. The deliverables include the terminology records, the tree diagram, the translation and also a commentary on information retrieval, exploration of terminological knowledge and translation decisions.

Students’ commentaries of their decision regarding the transfer of two specialized metaphors from English to French provided the basis for further analysis in this paper of the alternatives and the resulting linguistic and ethical issues. The first student explored the expanding domain of “shadow banking”. While she was fully aware of the problem of finding a plausible equivalent in French for “shadow banking”, she did not go much further than listing some alternatives. Further research was required for the present paper in order to assess the impact of these alternatives, described below. This was not the case with the second student who fully explored the consequences of choices to translate the concept of “human branding” and provided extracts of her correspondence with an expert in the field. Consequently, while the first case study only uses the student’s report as a starting point, the second study summarizes and comments on the student’s analysis of her own choice.

3.1. The Case of “Shadow Banking”

The study given below is based on the student’s identification of the alternatives for the translation in French of the English term “shadow banking”. This identification enabled us to further explore the origins of the term and the impact of its transfer into another language. Following a brief presentation of the concept, a general press database is used to provide a diachronic analysis of the emergence of the term in English and in French. Evidence is then given of the variants in the French translation. The term is finally studied as a lexically productive metaphor, which leads to an assessment of the consequences of the translation choices.

3.1.1. The Concept and Its Emergence

This is how the IMF (International Monetary Fund) defined the concept of “shadow banking” in 2013:

“The shadow banking system can broadly be described as credit intermediation that involves entities and activities (fully or partially) outside the regular banking system or non-bank credit intermediation in short.”

These unregulated financial activities have very often been accused of being partly responsible for the global economic crisis, which spread from the USA as from 2008. This is what Laura Kodress, assistant director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, writes in an IMF publication, in 2013:

“If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and acts like a duck, then it is a duck—or so the saying goes. But what about an institution that looks like a bank and acts like a bank? Often it is not a bank—it is a shadow bank. Shadow banking, in fact, symbolizes one of the many failings of financial system leading up to the global crisis”.

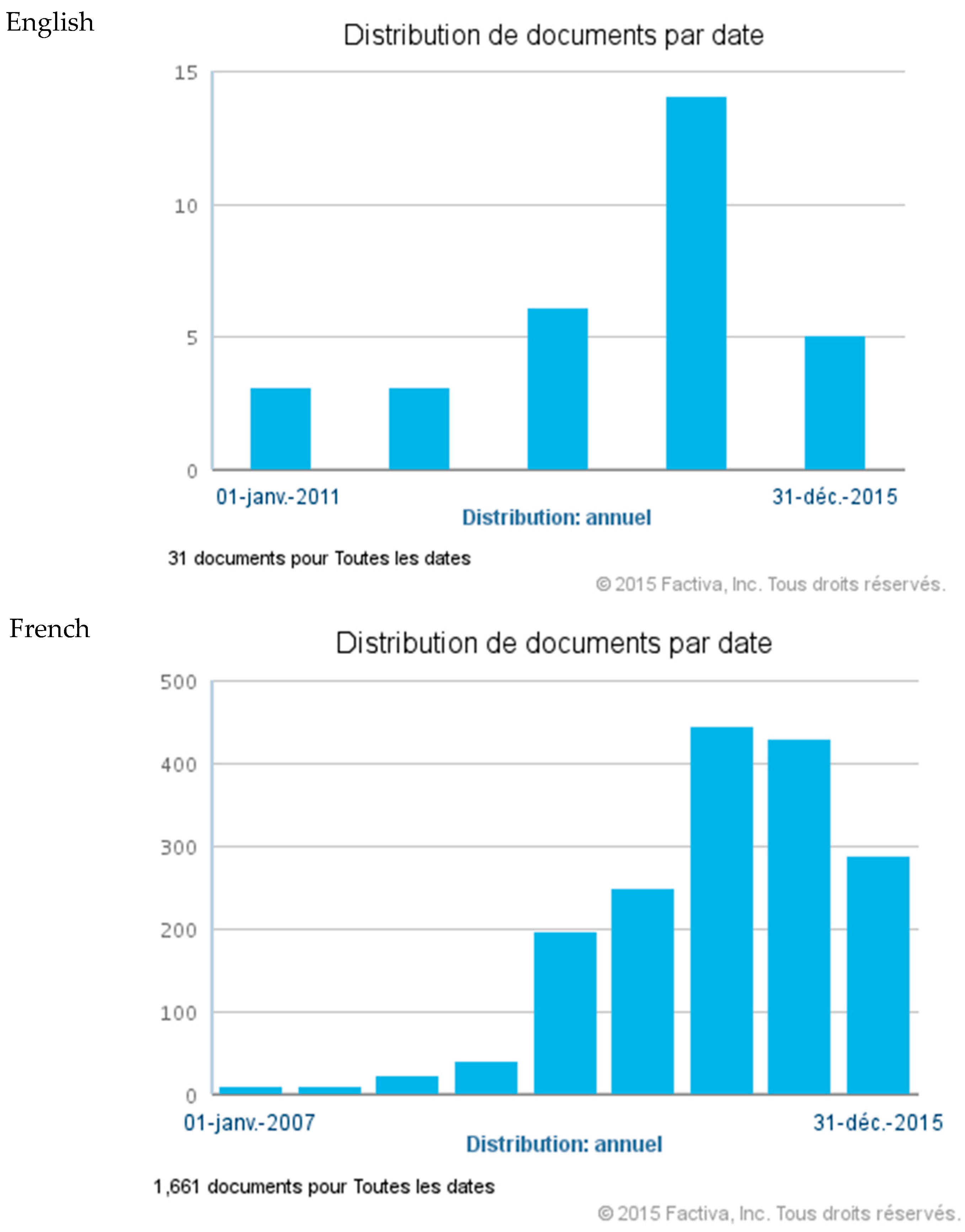

In her report, the student describes the context of the term’s emergence in relation with the 2008 global economic crisis and offers several examples of uses of this term in various contexts, in the general and specialized press and by the financial institutions. To better understand the conditions of emergence of this neologism, and for the purpose of this paper, the press database Factiva was used to offer a more systematic statistical and diachronic comparative approach. Factiva database provides economic and financial information from 36,000 sources, 200 countries and 28 languages. The figures given below show diachronic charts extracted from it. Selecting English-language sources combined with the term “shadow banking” with no date limit produces a selection of 27,624 documents. In contrast, selecting French sources featuring the term “shadow banking” (in English) with no date limit produces a selection of 1661 documents.

Figure 1 shows that, while the term “shadow banking” appeared in the English language economic literature 30 years ago, it experienced a spectacular rise in 2007, just preceding the start of the latest global economic crisis. The term first appears in the French press in 2007 and its use rises in 2011, reflecting the delay between the start of the crisis in the USA and the full extent of its impact in Europe.

3.1.2. “Shadow Banking” in French

As shown in

Figure 1, the diachronic distribution of the term shows that the use of the term “shadow banking”, borrowed from English, is obviously much more recent in French than in English; it has recently undergone a spectacular rise, in the last seven years, starting from 2009 in English, and 2011 in French. The French press also uses several French alternatives to the English term: “

banque de l’ombre”, “

banque parallèle”, and “

finance de l’ombre” as in the following examples, taken from the daily newspaper “Libération”:

Eg. 1 75,000 milliards. C'est, en milliards de dollars, le poids de la finance de l'ombre, plus communément appelé shadow banking et qui a continué de grossir en 2013 de 5000 milliards de dollars (3950 milliards d'euros), selon le Conseil de stabilité financière (FSB).

Eg. 2 Enfin, le développement d'un «système bancaire parallèle» (shadow banking system) constitué de fonds divers a permis d'échapper aux règles de capital puisque ces fonds n'étaient pas soumis en pratique à des contraintes réglementaires et de surveillance.

Eg. 3 Le Fondo sociale di cooperazione europea (FSCE) possédait toutes les qualités de la banque de l'ombre: un sigle trompeur, un statut hybride (quelque part entre Milan et Paris), une remarquable capacité à jongler entre les différents paradis fiscaux.

An alternative to the literal translation of “shadow” by “

ombre” is the use of “

fantôme” (ghost) as in “

banque fantôme”. This title taken from the French daily economic newspaper Les Echos is an interesting example, all the more so as the concept of “shadow”, replaced here in favor of the term “

fantôme”, is however inserted in the sentence by a reference to a French idiomatic expression “

n’être plus que l’ombre de soi-même”:

Eg. 4 “Dexia, l’étrange destin d’une banque fantôme” followed by: “Quatre ans après sa faillite retentissante, l'ancien géant bancaire franco-belge n'est plus que l'ombre de lui-même»

While there is not much quantitative difference between the use of these variants in the general press, the French economic specialized press tends to predominantly borrow the English term, as shown by a query in the economic press database Factiva, with a result of 1606 occurrences for “shadow banking”, as opposed to 49 for “banque de l’ombre” and 64 for “banque parallèle”.

3.1.3. “Shadow Banking” as a Metaphor

These variations around the themes of light, shadow and ghost shed light on the strong metaphorical power of the image of “shadow banking” due to the double meaning of “shadow”.

The literal meaning of shadow is “a dark shape that appears on a surface when someone or something moves between the surface and a source of light” (Merriam-Webster). This meaning may lead to somber connotations of a hidden, possibly dangerous reality, where light is opposed to darkness, as in the “dark side of the force”. “Shadow” may also refer to a reflected image or a copy. Thus, “shadow” in politics, as in “shadow cabinet”, refers to the fact that every minister of the government is “shadowed” or “marked” by a member of the opposition.

“Shadow banking” belongs to a productive and complex metaphorical network, and refers to the essential contrast between light and darkness [

27], thus representing adequately the delicate balance between visible and invisible, regulated and unregulated banking activities.

Furthermore, the study of the English term in context shows that the term “shadow banking” and its co-occurring lexical network (e.g., “dark pool”, “soup”, “black hole”) are based on the “mapping” [

28] from the field of astronomy and exoplanets to the field of emerging forms of globalized economy. Here are two examples of this intertextual phenomenon:

Eg. 5 “A further layer of complexity and uncontrollability is added by what Yves Smith, founder of the influential Naked Capitalism financial Web site, has called “the heart of darkness”: the shadow banking system, or black hole of unregulated (and unregulatable) financial innovations, including bank conduits (such as structured investment vehicles), repos, credit default swaps, etc. The system is so opaque and risk-permeated that any restraints imposed threaten to destabilize the whole financial house of cards.” John Bellamy Foster and Hannah Holleman in The Monthly Review 2010 Vol. 62 Issue 1 3

Eg. 6 “The United-States:” primitive soup” of the financial turmoil

The rising US trade deficit and the build-up of United States of America's foreign debt have become to the world economy what a black hole is to the universe. In a black hole, the entire structure and behavior of matter changes. So, too, is the case with its economic counterpart.” Thurow, L. C., and Tyson, L. D. A. (1987). The economic black hole. Foreign Policy, 3–21.

This mapping transfers the mixed negative and positive connotations related with exoplanets and black holes: an invisible and therefore fascinating and scary new world. Consequently, “shadow banking”, in the English context, appears as either a natural evolution of the economy or a potentially dangerous drift of capitalism towards an unknown world. To that extent, the term effectively represents the uncertainties born from the globalized economy. One might even suggest that this invisible world is related to the famous and controversial “invisible hand” of the economy [

29] that is Adam Smith’s “un-observable market force that helps the demand and supply of goods in a free market to reach equilibrium automatically.” This very optimistic vision of the free market has also given rise to the much darker vision of an international and invisible financial conspiracy, a vision often tainted with anti-Semitism [

30]. The

Figure 2 below offers a representation of this mapping phenomenon:

The mapping phenomenon follows a process where the economic world borrows a lexical network from astronomy to express the development of a financial mechanism.

3.1.4. The Impact of the Translation Process in the Target Culture

Considering this very productive metaphorical “swarming” process [

19], the preference for the direct loan of the English term “shadow banking” by the French press has a double impact. Because it is unable to convey the original connotations attached to the English term, this choice sterilizes the imaging potential of the metaphor and its textualizing productivity. It also leaves the French reader with the impression that these new economic and financial phenomena are imported and imposed by the world of Anglo-Saxon capitalism in a process which cannot be opposed or discussed. By imposing a foreign term, the translation brings in another world which cannot be fully deciphered.

In so doing, it prevents the reader from developing a new knowledge in a specific “kind of territorial expansion”, which could be called “epistemicide” [

1] (p. 154). The alternatives offered by the French translations of the term and more specifically the colligation “

de l’ombre” do not offer the same balance, since they convey the clearly negative connotation of the hidden and threatening presence of a “man behind the scene” (in French, “

l’homme de l’ombre” or “

éminence grise”) or even a “ghost”. Therefore, the translator faces a frustrating choice between using the dramatizing and strictly negative French equivalents (“

finance de l’ombre”, “

banque fantôme”) or borrowing the English term and thus depriving the French reader of developing his/her own understanding of the term and its connotations. This unsatisfying alternative may be considered as an illustration of the danger of “register atrophy” or “slow impoverishment of the language’s lexical and stylistic resources through under-use” described by Gunnarsson regarding Swedish academic discourse ([

31] quoted by [

9]).

The student who studied this domain chose to sidestep this dilemma by using the infrequently attested but more neutral “système bancaire parallèle”, which she judged more appropriate for the institutional text she had decided to translate. While this choice implies the loss of the evocative and connotational power of the metaphor, it is coherent with her analysis of the genre.

3.2. The Case of “Human Branding”

“Shadow banking” is only one of many examples of the issues raised by the transfer of metaphor in specialized languages. Another case in point, presented by a different trainee translator, is the study of the concepts of “human brand” and “human branding” as opposed to “product brand” and “product branding”.

3.2.1. “Human Brand” and “Human Branding” as a Metaphorical Concept

The term “human brand” belongs to the Anglo-Saxon marketing world and refers to people who are turned into brands. They may be celebrities who “employ branding techniques such as managing, trademarking and licensing their names, launching their own product lines and agreeing to product endorsements to enhance their perceived value and brand equity.” [

32]. Therefore, these celebrities can be considered and treated as brands. “Human brand” may also designate ordinary individuals who self-market themselves as brands in order to attract prospective employers [

33].

While “human brand” only refers to humans in the world of marketing, “human branding” belongs to two separate worlds. In the field of anthropology, it refers to “the process in which a mark is burned into the skin of a living person, resulting in permanent scarification” [

34]. In the field of marketing it refers to the above mentioned strategy which turns a human being into a brand. It may take the meaning of a process in which “people can position themselves to be successful in any career pursuit” [

35]. In the subfield of political branding, it designates a marketing process based on the “value as a brand of a person who is well-known and subject to explicit marketing communications efforts” [

36].

Considering that the original meaning of “brand” and “branding” refers to the use of a piece of burning wood to mark property, the meaning of “brand” and “human branding” in the field of marketing can be considered as the result of a metaphorical mapping process, based on a common seme of belonging, identity and differentiation. The concept of branding has been transferred from the fields of anthropology and agriculture to the fields of marketing and management.

3.2.2. Transferring “Human Brand” and “Human Branding” into French

This polysemy cannot easily be transferred to French. First, the noun “human brand” cannot be translated literally by “marque humaine” since this French term refers to a type of brand connected with sustainable or “humane” development, as can be seen in this extract of a recent publication on management counseling [

37] (p. 103):

“On assiste en effet à une montée en puissance de nouvelles dimensions: «être perçue comme une marque humaine (…); attentionnée (…); respectueuse (…); sincère (…); sympathique (…)»”

The case of “human branding” is even more difficult since French marketing LSP has borrowed the English term “branding” to refer to a marketing strategy based on a brand, rather than using the French term “marquage” which only reflects the traditional meaning of marking ownership. Therefore, the term “marquage humain” (for “human branding”) strictly refers to physical branding of the skin as an artistic or masochistic act, and cannot be extended to the field of marketing. Neither the term “branding” nor “human branding” in the field of marketing have a French equivalent, an absence which might be interpreted as the sign of a cultural resistance to considering a human being as the equivalent of a product.

In this context, the trainee translator faced the alternative of either borrowing the English term or creating a new term. Queries on the web and in the student’s collected corpus showed that, contrary to what was the case for “shadow banking”, the English “human brand” or “human branding” were not used in a French textual environment. Studying her corpus with a concordancer, the trainee translator noticed that the term “

marque” was often part of another complex term formed on the pattern of “

marque-x”: “

marque-produit”, “

marque-entreprise”, “

marque-gamme”,

etc. These terms refer to the result of the transformation of an entity (product, company, range) into a brand. Therefore the student hit on the solution of transforming the pattern adjective + noun of “human brand” into the noun-noun pattern such as “

marque-x”, with x referring to a person. She had in fact identified a paradigm in French, and was thus able to add to this paradigm. The confirmation came from a systematic interrogation of the corpus using this regular expression. This interrogation resulted in the identification of several occurrences of “

marque-célébrité”, all coming from an essay written by a French expert who had coined this term to refer to a brand connected with an institution or a person [

38]. Consulted by email, the expert pointed to the recent extension in France of the concept of brand to human people and organizations

. Therefore, the student chose to use the term “marque-célébrité” despite the fact that it had so far only been used by one author. However, this solution could not apply to the translation of “human branding” as a process, since the term ”branding” has not been translated but transferred into French.

3.2.3. The Impact of the Translation Process on the Target Culture

While the translation of “human brand” as “marque-célébrité” expresses the connection between the worlds of anthropology and marketing through the common seme of belonging and differentiation, this is not the case with the borrowed term “human branding”.

Borrowing the English term also stops any kind of “swarming” metaphorical phenomenon likely to produce a semantic network of related concepts around the core concept of “marque”. To that extent, it could be said that the use of the term “branding” in the French LSP of marketing prevents this field from developing its own conceptual mapping, thus creating dependence on the Anglo-Saxon conceptual world.

4. Cultural Transfer of Metaphor and Domain Loss in Specialized Languages

This paper has shown how a reflective practice of translation can contribute to an exploration of the interaction between lexico-semantic variations, specialized terminology, cultural transfer and domain loss. The case of the translation of specialized metaphor was chosen as a vantage point to identify cultural gaps in globalized fields of knowledge, here economics and marketing, and to enable a better assessment of the nature of the ethical stakes behind a translation choice.

The analysis of the problems raised by the translation of specialized metaphor highlights the potential productivity of the semantic ambiguity created by the mapping process and the meeting of two conceptual worlds, as shown for instance in the case of “shadow banking”, based on a conceptual transfer from the field of “black holes” in astronomy to the emerging financial system of “shadow banking” in economy. This ambiguity leaves space for connotations and interpretation, which confers to the metaphor a rhetorical role comparable with the pivotal role of “shell nouns” [

39] or “signaling nouns” [

40] in scientific argumentation. Just as this type of noun (e.g., “this fact…”,

“the idea that…”) encapsulates and reclassifies the part of text it refers to, by offering clues for interpreting given portions of texts, the conceptual metaphor encapsulates ideas and phenomena into one image. In turn, the understanding of the metaphorical term requires an interpretation by the reader, which relies on cultural connotations.

Therefore, borrowing a metaphorical term from another culture reduces this space of interpretation, thus depriving the target culture of the possibility of assimilating and criticizing this new concept. It appears that the translation of a metaphorical term, in a given text and culture, should aim at preserving this ambiguity by transferring the partly empty semantic space created by the metaphoric mapping. The observation of the transfer process and the resulting alternatives also shows that the translation decision must take into account the semantic and lexical network created around the metaphor (e.g., “dark pool”, “soup”). As a result, the choice of borrowing the term from the dominant language results in the suppression of the metaphor’s imaging, conceptualizing and textualizing power. To that extent, the linguistic transfer becomes a tool of domination and disempowerment. Because the French reader is confronted with the foreign term of “shadow banking” which cannot be connected with its semantic origin, the term gives no space for interpretation. Besides, since the core term of “shadow” cannot be connected to a lexical network in French, the French LSP of finance is unable to develop a new terminological field, which results in potential loss of a specific native view or voice on this subject, i.e., a “domain loss”, paving the way for an epistemicidal phenomenon where French culture no longer has the means to conceptualize and modify this new field of knowledge.

In the case of “human brand” and “human branding”, the translator faces the absence of both the concepts and the terms in the target language. Therefore, the choice is between borrowing the English term or coining a new one. As shown in the case study, literally translating the English terms is impossible for linguistic reasons. While “brand” can easily be translated by “marque”, its combination with the adjective “humaine” as in “marque humaine” may lead to a misunderstanding, due to the polysemy of the French adjective. The proposed term “marque-célébrité” is a compromise since it takes into account the French reluctance to consider humans as brands but it gives a restrictive interpretation of the polysemous “human brand”.

In the case of “human branding”, the use, in the language of marketing, of a term borrowed from English for the core concept of “branding” stops the formation of a lexical network around the potential equivalent “marquage”, only used in French for scarification. The implications of this case study are twofold: the transfer of a single core concept, here “branding”, deprives the French actors of the field from developing their own epistemological approach. The creation of a new term, here “marque-célébrité” involves taking the responsibility of naturalizing a concept and its ethical implications in a culture which might not be ready for it.

With all their differences, both case studies and the translation choices they involve show that lexical choices impact the development of specialized languages other than English. While borrowing terms from other languages has been a historical factor involving creativity, importing terms from a dominant culture can have counter effects on this productivity since it deprives the new terms from the connotations which enrich them in their original context and also hinders the development of a new metaphorical network in discourse. Therefore, translators, scientists and technical writers should be aware of the implications of their lexical choices. The translation decision requires a combined assessment of the discourse community, the communicative intention and more generally Malinowski’s “context of situation” and “context of culture” [

41]. Learning to translate implies developing an awareness of global issues and the way they can orientate discourse communities’ textual processes. It should also enhance recognition of the translator’s and the writer’s responsibility in the creation of new terms in specialized languages and in setting opportunities within other cultures to express their view on a new concept.