Abstract

The editorial policies of science journals have an impact on access to scientific knowledge. One of the most effective ways to share knowledge with the entire society is to offer it free of charge. Considering the international recognition of Scopus and Web of Science, this study analyses 28 scientific journals in the field of communication that are indexed under the “Communication” category in both databases in order to review their editorial decisions regarding the dissemination of articles they publish. By taking a descriptive approach, the authors have examined the inner workings and design, as well as aspects related to ethics and transparency, as key components of this policy. The findings indicate that most journals are influenced by digital publishing platforms and that various features examined in this study are offered by these platforms by default. This is especially true in terms of design, which simultaneously enables yet influences each journal’s editorial policy. Together with the need for financial support and adequate human resources, this situation makes it difficult to implement an editorial policy free of external encroachment. This article concludes by emphasising the importance of establishing editorial policies that promote open access as a standard practice, thereby reinforcing the democratisation of access to scientific knowledge. It is recommended to strengthen institutional support for journals operating under the diamond model, promote their visibility and thematic specialisation, enhance technical and visual aspects, and clearly articulate ethical commitments within their editorial policies. In short, this analysis provides a comprehensive overview of both strengths and areas of improvement, offering recommendations to help these journals optimise their contribution to the global academic ecosystem.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, Latin America has experienced remarkable growth in scientific production in the field of communication, largely driven by its network of universities, policies that encourage open access, and a long-standing commitment from public administrations (Babini, 2019; Barranquero Carretero & Ángel Botero, 2015). Science journals play a key role in this growth, as they are not only channels for disseminating research but they also serve as venues for bringing together academic communities (Gonzalez-Pardo et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Benito et al., 2023). In addition, they play an essential role in academic promotion and in developing the prestige and reputation of authors (Baiget & Torres-Salinas, 2013; Delgado et al., 2007). However, this development has not been consistent, nor has it been without challenges for the editorial teams of journals that act as gatekeepers for the success of publications.

Despite an increased number of journals, in addition to more variety and scope, their international presence remains limited (Higuchi et al., 2024; SCImago, 2025). Numerous studies indicate that communication journals in Latin America are still underrepresented in databases such as Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). In fact, less than 5% of the communication journals in this region are indexed in these databases (Arroyave-Cabrera & González-Pardo, 2022; Demeter et al., 2022). Among other factors, this situation is a reflection of evaluation criteria that are still strongly linked to bibliometric and linguistic parameters that prioritise production in English and in countries in the northern hemisphere (Asubiaro et al., 2024; Beigel, 2014).

In this framework, the analysis of editorial policies is seen as a way to improve the understanding of the structure, orientation, and ethical commitment of journals, regardless of their visibility in the main bibliometric indicators. Editorial policies define the principles, procedures, and responsibilities of everyone involved in the science publishing process (Sánchez-Tarragó et al., 2016). These refer to statements made by journals on key issues such as the type of research they accept, the access model, submission guidelines for authors, peer review criteria, and the use of publishing technology (Demeter et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Benito et al., 2023). In Latin America, the dominance of the diamond open access model, which has no costs associated with publication or access, is a distinctive feature of the region’s publishing ecosystem (Uribe Tirado, 2023). The principle of free access on which the diamond model is based is supported by universities, cooperative networks such as SciELO and RedALyC, and, most importantly, by an academic ethic that views science as a public asset (Aguado-Guadalupe et al., 2022; Tur-Viñes, 2023). However, the unique features of this model have not been considered relevant by international evaluation systems, resulting in a lack of visibility for both the journals and the scientific literature published therein (Asubiaro et al., 2024).

Despite various types of support available to develop publishing, funding shortages and difficulties in recruiting editorial staff, as well as deficiencies in technological infrastructure, limit the ability of many journals to establish editorial policies that meet the standards of Scopus and WoS (Gonzalez-Pardo et al., 2020; Ortega-Mohedano et al., 2023). In this regard, there has been a clear trend toward embracing editorial policies that are in line with international standards in an effort to improve the indexing and visibility of these journals (Gonzalez-Pardo et al., 2020). This has encouraged the inclusion of aspects related to ethical commitment and transparency in scientific publication (Hernández-Ruiz, 2016). In fact, it is increasingly commonplace for editorial policies to include a declaration of conflicts of interest, the disclosure of funding sources, copyright management, and the incorporation of anti-plagiarism software (Demeter et al., 2022; Segado-Boj et al., 2024).

Moreover, examining editorial policies is an effective way of understanding how journals approach the challenge of becoming international. Although most of the publications in the Latin American region are affiliated with institutions in their respective countries, there is a perceived openness to accepting articles in other languages—mainly English—and to internationalising review panels, editorial boards, and scientific committees (Rodríguez-Benito et al., 2023). However, in terms of structure and of who is involved in these journals, at the end of the day, this openness does not result in either diversification or internationalisation of authorship, as production is still concentrated in a few universities in the region (Arroyave-Cabrera & González-Pardo, 2022; Gonzalez-Pardo et al., 2020).

Another key aspect in the development of these journals is the need for specialisation among editorial teams. Many operate with limited staff, no apparent editorial training, and with conditions that have come to be known as academic volunteering (Gonzalez-Pardo et al., 2020). Undoubtedly, this has a direct impact on the quality of the journals, and it even presents the following paradox: There is a perception that the journals which contribute most to the dissemination of scientific knowledge due to having open access are, at the same time, those that face the greatest difficulties in being recognised as quality journals according to today’s prevailing criteria (Aguado-López et al., 2024; Uribe Tirado, 2023).

Consequently, expanding knowledge regarding the leading science communication journals in Latin America, based on the categories and classifications established in the field of communication by the main international databases—Scopus and WoS—is aimed at improving the journals themselves, as well as the networks and communities that develop around them. Therefore, the present analysis aims to identify best practices and areas for improvement, with the aim of contributing to a fair, open, and contextualised view of the publishing ecosystem in relation to the dominant rationale (Piñuel Raigada et al., 2016; Waisbord, 2014). Reviewing editorial policies provides insight into the strategies used by journals to meet current indexing and visibility requirements, in addition to enabling issues of interest regarding the editorial management processes to be identified.

2. Objectives and Methodology

The overall objective of this study is to explore the editorial policies of science communication journals in Latin America, indexed in Scopus and WoS, to identify the different strategies they have adopted. The full list of journals included in this study can be found in Appendix A. In addition, the following specific objectives are set forth:

- OE 1: Assess the degree to which these journals are in line with editorial quality criteria.

- OE 2: Identify and describe the basic features of editorial identity.

- OE 3: Analyse the features of the journals’ websites.

In order to address the objectives set out in this research, this study is grounded in content analysis as the primary methodological approach. Through the application of this methodology, data were systematically collected. The findings derived from this process are presented in detail in the Results Section. This method is considered “a research technique designed to formulate, based on certain data, reproducible and valid conclusions that can be applied to their context”, Krippendorff (2002, p. 28). To conduct the survey, an ad hoc coding system was developed for data collection. This instrument was configured as a spreadsheet in which eighty-three features of each journal were reviewed and divided into six blocks, as shown in the summarised version provided in Table 1; a detailed explanation of the instrument can be found in Appendix B.

Table 1.

Summarised version of the coding system.

The coding system is based on the guidelines outlined in the document Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing (COPE, 2022), as well as on the criteria set out in Content Policy and Selection for Scopus (Elsevier, 2024) and Journal Evaluation Process and Selection Criteria for WoS (Clarivate, 2024).

This work is based on information available to the public on each journal’s website. Thus, further information can be accessed upon registration. However, this feature is beyond the scope of the present study.

All three authors participated in the data collection. To verify the data collected, this process was conducted three times, and any doubtful cases were discussed until an agreement was reached. The present research has verified the degree of reliability of content analysis when applied by diverse coders, which guarantees the reliability of the technique and ensures comparable results regardless of the evaluator. As pointed out by Wimmer and Dominick (1996, p. 144), “If content analysis is to be objective, its measurement and procedures must be reliable. […] Reliability is present when repeated measures of the same material lead to similar conclusions or decisions”. To achieve this aim, different coders must reach a high level of agreement in their analysis of the different categories.

Krippendorff’s (2002, pp. 197–199) Alpha Index was used to review the agreement reached among all the coders based on the level of measurement of the variables addressed. In other words, we refer to the variables that require interpretation by the coder. The results yielded scores above 0.9 for the three coders, indicating a high degree of internal consistency of the indicators among the variables evaluated. The coding and analysis work was conducted during January, February, and March of 2025.

Finally, the target population consists of the 28 science communication journals from Latin American countries indexed in Scopus and WoS. These databases were selected due to their selective nature and because they include scientific journals that are regarded as the most prestigious at the international level (Singh et al., 2021). To this end, lists from both databases were downloaded in May of 2025 from JCR and SJR, respectively. It should be noted that the journal entitled European Political and Law Discourse was not included in this study because, although it is listed as a Paraguayan1 journal following the latest update of Scopus, the periodical is from the Czech Republic. In this study, the association between journals and nations is determined by the country of the publishing institution. The consolidated list of journals is based on data from WoS for 2023 and Scopus for 2024, which are the most recent available at the time of conducting the research.

3. Results

The results provide an overview of the state of science communication journals in Latin America that are indexed in WoS and Scopus. These are organised into different blocks by grouping together the 83 items reviewed as follows: identification; platform; visibility; open access, ethics and transparency; social media; design and editorial identity. Moreover, it should be noted that most of the twenty-eight journals that make up the sample are also present in other categories, both in Scopus and WoS. However, in the present study, regarding issues of journal visibility, only information related to the communication category was considered. The results presented below are based on the analysis of the 28 scientific communication journals included in this study. These journals are indexed in the Scopus and WoS databases: 22 are indexed in Scopus and 13 in WoS. A total of seven journals are indexed in both databases.

3.1. Identification

In terms of publisher identifiers, all the journals analysed have an ISSN (International Standard Serial Number), which is registered on the ISSN Portal2, in line with standard practice for periodical publications. These identifiers are available in both print and electronic formats and, in all cases, are active according to the information on the ISSN Portal. On the other hand, the DOI (Digital Object Identifier) has not been universally adopted, although its use is now quite significant, appearing in 85.71% (n = 24) of the journals.

Regarding institutional dependence and publishing models, most of the journals analysed (85.71%, n = 24) have links to universities, which is the most common situation. A total of 58.33% (n = 14) said they were part of specific academic units, such as faculties, departments, or specific areas. The rest were divided between higher education centres and professional associations (two journals in each category). In terms of publishing management, nearly all the journals are managed by one governing body (96.30%). The exception is the Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social Disertaciones, which uses a co-publishing model involving universities in Colombia, Venezuela, and Spain3.

As shown in Figure 1, the geographic distribution of the journals shows a strong concentration in Brazil, which accounts for 46.43% of the total (n = 13). Chile ranks second with four journals (14.29%), while Argentina and Colombia have three publications each (10.71%). Peru has two journals (7.14%), while Uruguay, Ecuador, and Mexico complete the sample with one journal each (3.57%).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the science journals analysed.

In terms of chronology, the journals were launched between 1972 and 2012, with a significant increase during the first decade of the 21st century (2000–2009), when 13 journals were published (46.43% of the total). This growth coincides with factors such as the global expansion of internet access and the development of specialised technology for scientific publishing4.

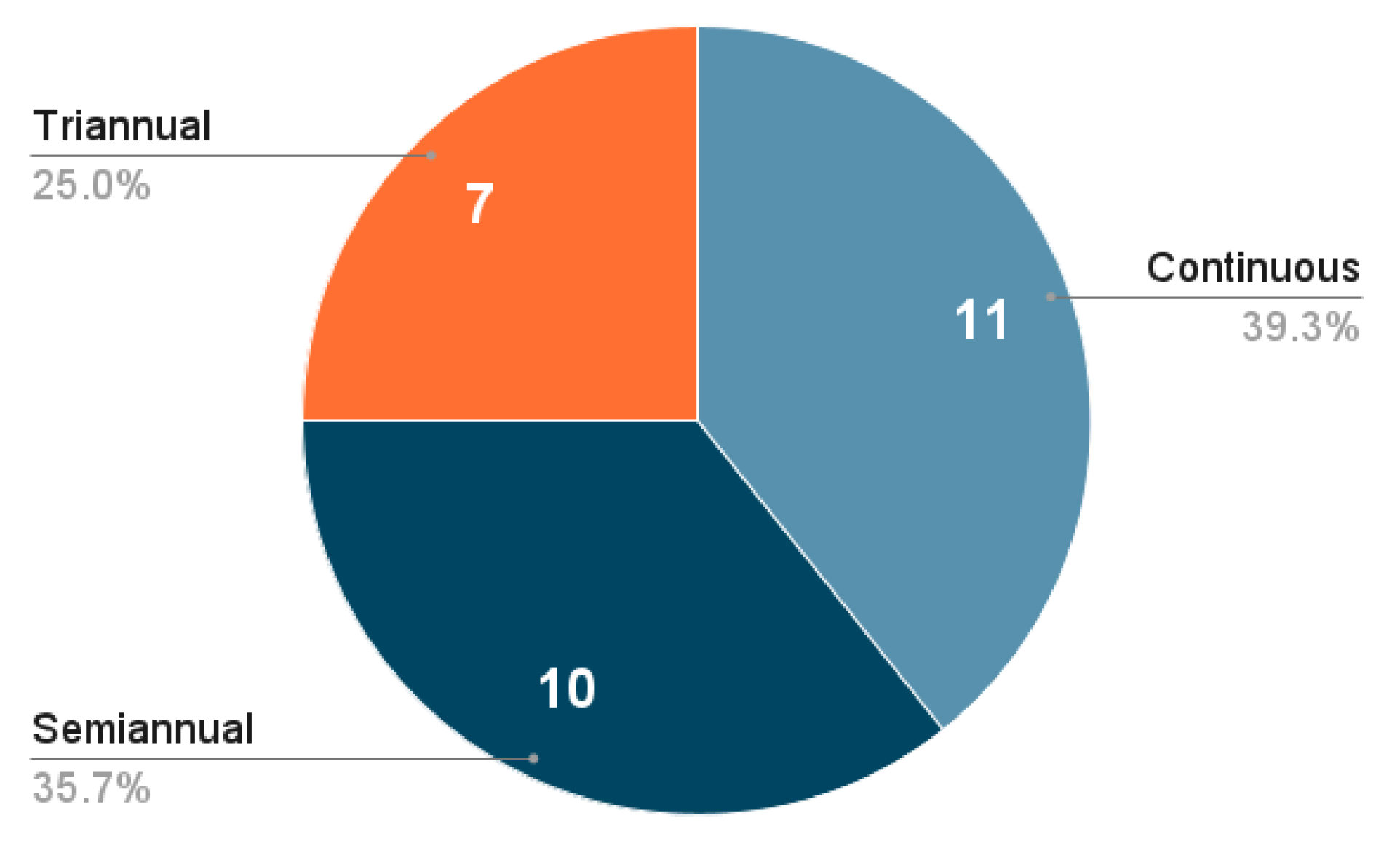

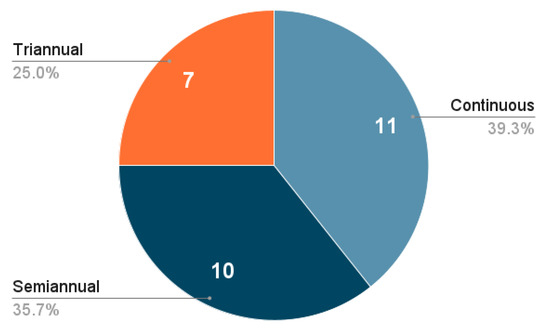

According to Figure 2, the analysis of frequency reveals three main models5 among the journals in the sample. Continuous publication is the most common, accounting for 39.29% (n = 11), followed by biannual (35.71%, n = 10) and triannual publication (25%, n = 7). It should be noted that all journals that currently use the continuous publication model have recently migrated from traditional systems such as biannual or triannual publication. This transition is clearly documented in the information sections of the journals and reflects deliberate publishing strategies.

Figure 2.

Frequency of journal publication.

A large variety of topics are addressed, with a total of 68 themes listed in the various descriptions provided by the journals regarding their content. As previously mentioned, it should be noted that even though all the journals are indexed in the “communication” category in the Scopus and WoS databases6, they also include associated topics from other fields of knowledge that correspond to other categories. For example, the category of “linguistic studies” covers twelve subject areas ranging from theoretical approaches to linguistics to practical applications related to translation. Likewise, the category of “information and documentation” includes seven themes covering areas such as library science, documentation, and archiving.

3.2. Platform

The examination of publishing platforms confirms the hegemony of Open Journal Systems (OJS), which is used by 96.43% of the journals analysed (27 out of 28). Only one Brazilian journal uses an alternative technological platform based on WordPress for its website, together with ScholarOne for editorial workflow, and SciELO Brazil as an access point for articles and the digital repository. Table 2 shows that a wide variety of OJS versions are in use: while 92.86% use 3.x versions, especially 3.3.x (57.14%, n = 16), some journals continue to use obsolete versions such as 2.x (7.14%, n = 2).

Table 2.

Versions of OJS identified in the sample.

Regarding the web interfaces of the journals, there is a clear commitment to multilingual accessibility, as they transcend the language of the country of origin. Of the journals analysed, the most common language configuration is trilingual, including Spanish, English, and Portuguese, which are present in 64.29% of the cases (n = 18). To a lesser extent, bilingual versions were identified (17.86%, n = 5), as well as platforms offering four languages (10.71%, n = 3), and sometimes even five (3.57%, n = 1), in addition to a single case that uses only English (3.57%, n = 1). English stands out for being universally embraced (100%), serving as the lingua franca of academia. As for regional languages, Spanish appears on 92.86% of the platforms (n = 26), while Portuguese is used on 75% (n = 21). This linguistic distribution varies by country: 91.67% of Brazilian magazines include Spanish versions, while 73.33% of publications in Spanish-speaking countries include Portuguese. Languages such as French and Italian are more limited, appearing in only two and three magazines, respectively.

On the other hand, editorial policies regarding acceptable languages reflect patterns similar to those observed in web interfaces, yet with certain differences. The most common policy is to accept articles in three languages (39.29%, n = 11), followed by two languages (28.57%, n = 8). Less frequent options include accepting articles in four languages (17.86%, n = 5) and a single language (14.29%, n = 4). The combination of Spanish, English, and Portuguese is the most widespread, appearing in a total of 13 journals (46.43%). However, unlike web platforms where English has been universally embraced, no single language reaches 100% in this area. Spanish leads with 89.29% (n = 25), followed by English (71.43%, n = 20) and Portuguese (67.86%, n = 19). In addition, five journals accept articles in French (17.86%).

Regarding display, all the journals use PDF as their standard format to publish articles. Some of them (25%, n = 7) complement this option with HTML versions, and one journal incorporates the EPUB format.

In terms of resources and tools available, there is considerable diversity on the publishing platforms analysed. Statistics that measure the access and use of the articles is the most widely used complementary service, which is present in half the journals examined (50%, n = 14). In terms of measuring academic and social impact, there is a balance between traditional and alternative metrics. The latter, alternative metrics, which gauge the social impact outside the academic realm, are used in 17.86% of cases (n = 5), while traditional metrics are employed in 21.43% (n = 6). Two specific journals stand out in their implementation of innovative technology: firstly, Comunicación y Sociedad, which uses an AI-based conversational assistant to facilitate interaction with users; and secondly, Discursos Fotográficos, which uses the VLibras suite7 to automatically translate content into sign language, thereby making a significant improvement in accessibility for deaf people.

3.3. Visibility

Focusing on visibility issues, and as shown in Table 3, it was found that most of the journals studied (96.43%, n = 27) provide information on their web platforms regarding indexing. Regarding the visibility of the main output of science publishing, one aspect bears mentioning. Even though all the publications use an open access model, two journals are not registered in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). Moreover, the use of Latindex is also widespread, while Dialnet is employed by 67.86% (n = 19) of the journals, and only the Brazilian journals were not present. In terms of the Scopus and WoS databases, various levels of participation have been observed: 78.57% (n = 22) of the journals analysed are indexed in Scopus, while WoS is considerably lower at 46.43% (n = 13). Only seven journals appear simultaneously in both databases, representing 25% of the sample, and all publications in WoS are included in the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI).

Table 3.

Indexing of the journals in the sample.

In terms of quartile positioning, there is a noticeable concentration in the lower quartiles (Q3–Q4) with regard to both indexation systems8. Of the journals indexed in Scopus, 77.27% (18 out of 22) are ranked in these quartiles, while the remaining 18.18% (4 journals) are in Q2. This trend is even more striking in WoS, where 92.31% of publications (12 out of 13) are in the third and fourth quartiles, and only 1 journal is in the top rankings (Q2). A direct comparison between the seven journals in both databases reveals discrepancies: four are higher in Scopus than in WoS, while three are ranked the same in both databases.

The process of incorporating journals into these databases also differs: Scopus maintained a steady pace from 2007 to 2019, with one addition in 2024, and a record number of journals included in a single year (five journals in 2019); WoS, on the other hand, added a staggering 84.62% (n = 11) in 2020, while the remaining two were added in 2021 and 2023.

3.4. Open Access, Ethics, and Transparency

All the journals examined operate under an open access model, with no evidence of hybrid or subscriber-based strategies. In terms of the open access model used, an overwhelming majority of 96.43% (n = 27) prefer the diamond model, which is free of charge for both readers and authors. Only one journal follows the paywall model, which requires authors to pay APCs, or Article Processing Charges. As mentioned in the previous section, one aspect bears mentioning: Even though all the journals adhere to open access principles, two of them are not registered in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

As for types of licences, Creative Commons is used by all the journals to regulate the rights of use and distribution of published content. However, there is some diversity in the specific variations of licences selected. The one known as CC BY can be reused without limit, as long as the original authorship is acknowledged. It is the most common within the sample, used by 46.43% (n = 13) of the journals. However, several publications prefer other licences, even though they impose additional restrictions. These include the following: CC BY-NC is used by seven journals (25%) but is not for commercial use; CC BY-NC-ND, used by three journals (10.71%), which does not allow content modification; CC BY-NC-SA is used by four journals (14.29%), but it requires derivative works to be shared under the same licence; and CC BY-ND, which is used by only one journal (3.57%), allows commercial use but not modifications.

As for digital preservation systems, all editorial policies specifically mention having instruments designed to ensure the long-term preservation of published content. Although the technical protocols used for this purpose are not always specified, a commitment to preservation appears to be a common feature of all the publications included in the sample.

Furthermore, most journals include a section on ethical information in their editorial policies. Specifically, 82.14% (n = 23) have a specific area where they detail the rules and principles related to publication ethics.

Regarding the use of artificial intelligence, only a minority of the journals address this issue in their editorial policies. Notably, 21.43% (n = 6) explicitly mention the use of AI by providing guidelines on how it should be applied, through statements such as “The use of AI tools should be explicitly stated by the authors in the manuscript, in the methodological section, detailing which tool was used and for what purpose” in the case of Dixit, or “If generative artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of the article, authors must disclose this information—detailing how it was used—in the Comments to the Editor section at the time of manuscript submission” in the case of Cuadernos.info. The use of these guidelines is limited to authors, as transparency in the use of these tools during the writing and editing of manuscripts is important.

In terms of privacy, nearly all the journals analysed show a high level of commitment to personal data protection. In total, 92.86% (n = 26) of the periodicals include specific sections in their editorial policies explaining how they manage and protect the data of authors, reviewers, and readers, with only two journals failing to provide any information in this regard.

The use of unique identifiers for authors is also a widespread practice among the journals studied. Thus, of all the journals, the same figure of 92.86% (n = 26) implement this resource and, in all cases, they choose ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID) for this purpose. By contrast, as for the identification of institutions, coverage is limited. In fact, of the entire sample, the ROR (Research Organization Registry) identifier appears in only three journals (10.71%).

Regarding the dates of the editorial process, there is diversity in the approaches taken in each case. The majority (64.29%, n = 18) report the dates when the articles are received, accepted, and published. Three journals offer more detail by including additional phases, such as the date of peer review or submission for blind review. However, in some cases, information is limited: One journal only mentions the dates when articles are received and accepted; three only indicate the date of publication on their website but not in the PDFs; and two provide no information about dates related to the editorial process.

Journals that refer to the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) in their policies show a strong commitment to ethics in science publishing. Of all the journals, 75% (n = 21) specifically mention compliance with the principles and guidelines of COPE, highlighting their adherence to recommendations related to academic integrity, uncovering malpractice, and resolving ethical conflicts. This aspect is addressed through statements such as “The Revista de Comunicación adheres to international norms and codes of ethics established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (Code of Conduct and Best Practices Guidelines for Journal Editors, COPE)”, as found in Revista de Comunicación; or “The journal Comunicación y Sociedad observes ethical codes for reviewers, authors, and editors based on the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), established in 1997 and with over 12,000 members worldwide, available at publicationethics.org”, as stated by Comunicación y Sociedad. By contrast, the remaining 25% (n = 7) make no reference to this organisation in their policies, although this does not necessarily imply an absence of ethical criteria in their work. It bears mentioning that none of the journals included in the sample are listed as official members of COPE.

The use of anti-plagiarism software is another widespread practice among the journals analysed. In their editorial policies, a total of 64.29% (n = 18) specifically mention the implementation of such tools as part of the review and quality control process. On the other hand, the remaining 35.71% (n = 10) make no direct reference to the use of these programmes in their guidelines. However, as with COPE, this does not necessarily mean that anti-plagiarism software is not used in the editorial processes of these journals.

As for the requirements related to authorship, data availability, conflicts of interest, and funding, implementation varies among the journals. Only 25% (n = 7) indicate that the contributions of individual authors should be detailed as part of the editorial process. The disclosure of research data appears in 46.43% (n = 13) of the policies, while 50% (n = 14) include a statement in their policies related to conflicts of interest. Finally, the most frequently mentioned aspect is the identification of funding sources, which is required by 67.86% (n = 19) of the periodicals. Although many journals claim to follow the general ethical guidelines recommended by COPE, the specific indication of these practices in the editorial guidelines varies considerably among them.

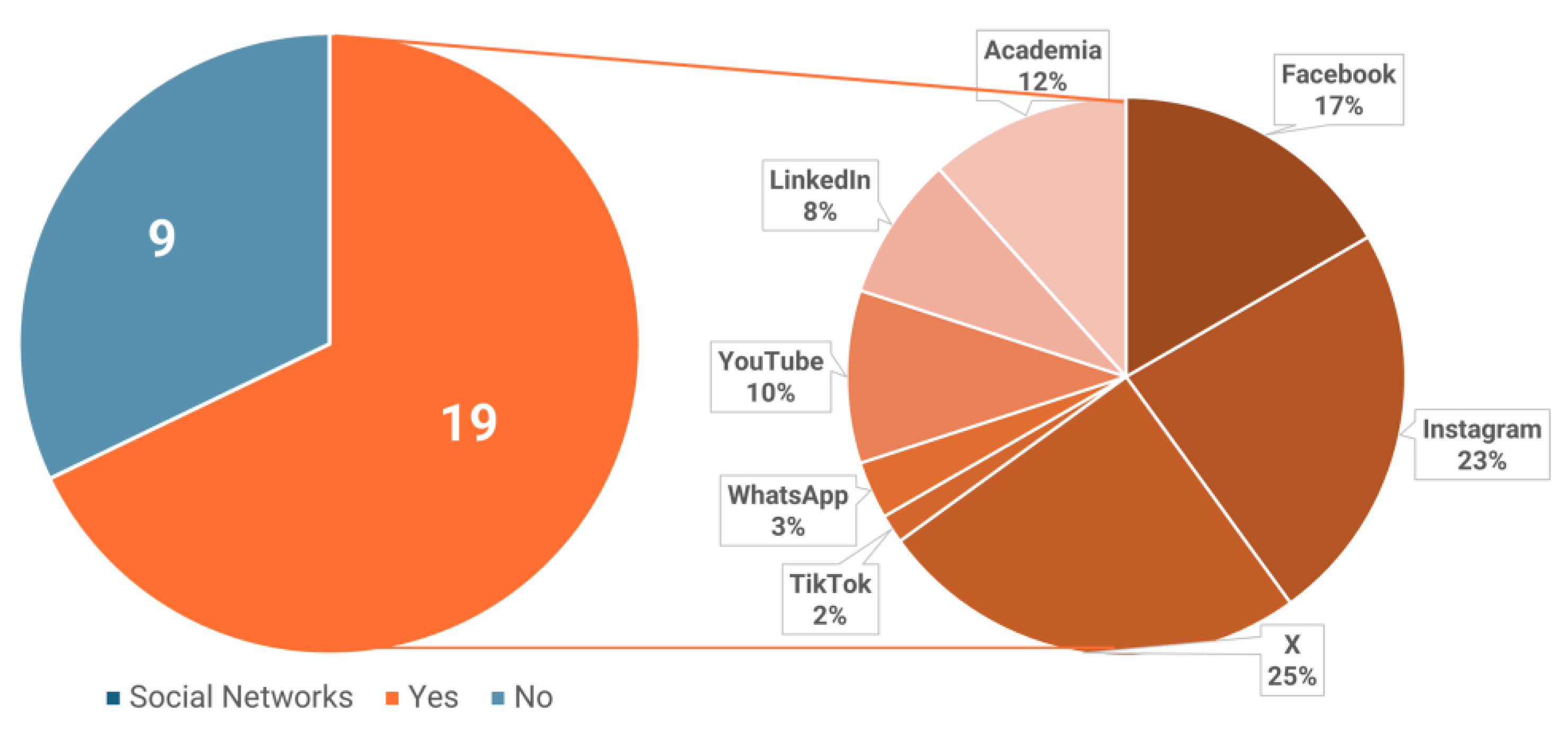

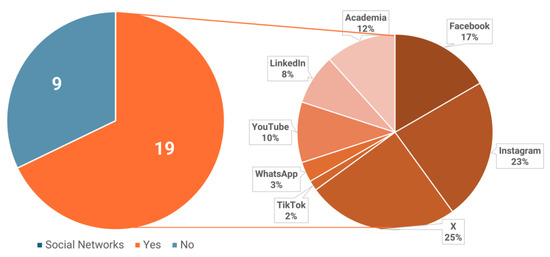

3.5. Social Media

In terms of being present on social media, a total of 67.86% (n = 19) have active profiles on at least one platform, which means that 32.14% (n = 9) have no presence whatsoever on these sites. Figure 3 illustrates clearly that, among generalist platforms, X (formerly Twitter) dominates and is used by 53.57% (n = 15), followed by Instagram (50%, n = 14) and Facebook (35.71%, n = 10). Other platforms such as YouTube and WhatsApp are used modestly by the journals, with six and two journals, respectively, and TikTok is only used by one periodical. On the other hand, specialised social media platforms have a lower rate of use: Academia.edu and LinkedIn are used by seven (n = 25%) and five journals (n = 17.86%), respectively.

Figure 3.

Journals with social media accounts (left) and the distribution of social media among journals with accounts (right).

3.6. Design and Editorial Identity

The practice of including specific covers for each issue is widespread among the journals analysed. In total, 85.71% of the periodicals (n = 24) use this graphic resource as part of their visual identity.

Regarding the use of a graphic mark, 71.43% (n = 20) of the journals incorporate this feature. However, its implementation varies depending on the format: 64.29% (n = 18) include it in the web version, while 46.43% (n = 13) use it in the PDF files of the articles. Only 39.29% (n = 11) use it in both formats consistently, which reflects a lower level of visual uniformity among platforms.

As for using the colour line as a graphic resource, the analysis shows that 78.57% of the journals (n = 22) use this feature in their editorial design. There is a trend toward the use of cool tones, specifically blues, which account for 28.57% (n = 8), followed by greens, comprising 14.28% (n = 4). Red and black are used equally at a rate of 10.71% (n = 3). Other colours, such as brown, and combinations of red and purple, are less common and appear in only one journal. It also bears mentioning that two journals choose to vary their colour palette in every issue they publish.

A typographical analysis of the web versions of the journals reveals the use of 14 different variants, with a clear preference for fonts in the sans serif category. The most common is Noto Sans, which is used by 39.28% (n = 11) of the periodicals, followed by Noto Serif in nine cases (32.14%), and Montserrat (sans serif) in seven (25%). In terms of the number of fonts used, nearly half of the journals (46.42%, n = 13) use a single typeface, while the rest (53.57%, n = 15) use a combination of two. The most notable are Noto Sans (n = 11), Noto Serif (n = 9), and Montserrat (n = 7), although seven fonts were discovered in one individual publication, which indicates that using a diversity of fonts is unusual. On the other hand, PDF files are quite varied, with 37 different typefaces and no well-defined combination of patterns. Again, the Serif fonts are most prevalent, especially Garamond and Times New Roman, both of which are used in 17.85% (n = 5) of the cases, followed by Calibri (14.28%, n = 4). Only in two cases is Times New Roman used more than once, and one journal used 21 of the 37 fonts, which indicates more variation in the typographical criteria of the PDF format.

Although most periodicals adhere to what might be called typographic unity in the PDF format (n = 23), no clear patterns can be observed in the combinations, and in none of the cases analysed is there typographic consistency between the web and PDF formats. In other words, the journals do not use the same typefaces in both formats.

Lastly, regarding the use of templates for preparing manuscripts, only 25% of the journals analysed (n = 7) provide the authors with templates that can be edited. Regarding the use of predefined graphic styles, it was also observed that in 25% (n = 7) of the journals, instructions were provided to authors.

4. Discussion

Compliance with quality standards among the sample of journals is largely ensured by the fact that they are indexed in the Scopus and WoS databases. However, after reviewing the results of the research at hand, what is clear is that areas of improvement continue to exist, which must be addressed in order for these periodicals to adapt to current practices and trends. Based on the findings, the implications of the need for improvement are discussed, and strategies are proposed for optimising the performance and quality of these journals.

The universal adoption of the ISSN system contrasts with the partial implementation of the DOI, despite its advantages as a strong identifier (J. Liu, 2021; Zhu et al., 2019). This suggests that although these journals meet the basic identification requirements9, they are not yet taking full advantage of the tools that promote the location and visibility of the content they publish. The minimal use of DOIs could be related to the associated costs for the journals. Consequently, institutional policies that finance or enable their use are recommended, especially for newly emerging periodicals.

The prevalence of journals linked to universities reinforces the crucial and decisive role of these institutions in disseminating knowledge and, more specifically, in their support of open access journals with no associated costs, or the so-called diamond model. Thus, there is a clear need for institutional support for these publications (Tur-Viñes, 2023). Moreover, it is also important to consider that, without broader infrastructural and financial support, editorial projects risk being fragile and overly dependent on local dynamics.

In terms of geographical distribution, Brazil stands out as the leader due to its size. The presence of other countries in the region is limited, as Central America’s participation is scarce, and there is only one Mexican journal. Moreover, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Uruguay are absent. This raises questions about the unequal visibility of regional scientific output. Consequently, it is necessary to explore whether this is due to public research policy issues or other types of barriers. In this regard, the limited role of the co-editing model bears mentioning, even though it was present in only one journal. This suggests opportunities for collaboration that pool resources and broaden the publishing scope, although it also poses challenges related to editorial coordination and reaching a consensus on national criteria (Repiso et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Yunta & Giménez-Toledo, 2013).

In terms of the thematic scope of the journals, the diversity reflects the interdisciplinary nature of the publications and of communication as a discipline (Fernández-Quijada et al., 2013), which is also reinforced by their visibility in other categories of Scopus and WoS. However, this thematic breadth—while a strength from the perspective of epistemic diversity—may paradoxically work against these journals in terms of indexation and international recognition. As J. Y. Liu (2014) observes, journals that do not conform to conventional thematic paradigms, particularly those focused on local or interdisciplinary issues, tend to be systematically underrepresented in major international indexing systems.

In terms of frequency, continuous publication has surpassed traditional models such as biannual, quarterly, etc., suggesting a shift in the pace of academic publishing. Furthermore, there is evidence that this strategy is intentional, as stated by the journals themselves, as these periodicals are moving toward an innovative publishing model. The likely purpose of this move is to increase the visibility of scientific output that is published, thereby reducing the time it takes to disseminate the results.

By focusing on the discussion regarding which publishing platforms are used by the journals in the sample, the hegemony of OJS is evident, which reinforces its prominence as the benchmark platform. While this predominance reflects the accessibility and community-driven nature of OJS development, it also carries important implications for how editorial policies are structured and operationalized. The platform’s modular architecture and default configurations facilitate editorial workflows and also actively shape them, influencing key aspects such as the peer review process, metadata standards, licencing options, and indexing practices. In this sense, the platform functions as a technological framework that configures both the procedural and normative dimensions of scholarly publishing. Moreover, some of the journals still use outdated versions (7.14%), which implies security and compatibility risks10. These risks should not be understood merely as technical shortcomings but as reflections of deeper structural limitations, particularly in terms of institutional support and technical training. Consequently, both the choice and the version of the platform used are not neutral elements; rather, they play a causal role in shaping how editorial policies are designed, updated, and sustained.

In terms of languages, there is a multilingual panorama, both on the journals’ websites and in the scientific articles they publish. This situation reflects editorial strategies aimed at making the journals more international through the use of English, yet with a focus on regional contexts, which vary between Spanish and Portuguese in the sample.

Regarding the process of submitting articles, this review shows that PDF is the preferred format. Naturally, this is related to the criteria of technical accessibility and the presentation of content in standardised formats required by Scopus and WoS. However, this is not likely to impede the growth of other formats such as HTML or EPUB, which address the need to make digital content easier to read (Rovira et al., 2007).

The use of innovative tools is limited to a chatbot and a sign language interpreter, suggesting that these types of resources are not considered useful, despite current trends that promote a wider range of options. Furthermore, the modest presence of features offering information on the impact of articles bears mentioning, both in terms of traditional and alternative metrics. This is a reasonably viable area of improvement given the availability of plugins in OJS, as well as accessibility to the API (Application Programming Interface) of third-party tools.

As for indexing and visibility, the prominent role given to this area stands out, with 27 of the 28 journals offering space for this purpose, which highlights the importance of this issue in relation to the quality and reputation of the publications.

In terms of visibility, the presence of the journals in Scopus is notable, in contrast to less representation in WoS, as well as the concentration in lower quartiles (Q3–Q4) in both databases. This situation highlights the challenge facing these journals in terms of gaining visibility for their publications and international competitiveness, which mainly indicates the need to attract quality research capable of increasing the interest in these periodicals. This is also related to the modest positioning of the journals, as reflected by the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) in Scopus and the Journal Impact Factor (JIF) in Web of Science—both used as citation-based reference indicators—whose values can be consulted in Appendix A. It can reasonably be inferred that journals not included in these databases would display even lower citation metrics. To do so, useful strategies would include increased topic specialisation and the establishment of collaborative networks between journals. In terms of quartile positioning, it is striking that none of the journals are in the first quartile, and only a few are in the second, which reinforces the idea mentioned above. Furthermore, in the specific case of WoS, all journals are indexed through ESCI, which reflects their nature as emerging periodicals in the international ecosystem. This limited representation is not merely a question of attracting high-quality research but also reflects the epistemic hierarchies embedded in global indexing systems, which often privilege Euro-American academic axis publication models (Ekdale et al., 2022).

When it comes to open access and the method used for its implementation, there is no doubt that the journals in the sample are committed to offering open, high-quality science information. All the periodicals are available in open access format, and nearly all of them use the diamond model for this purpose, except for one, which highlights the need for institutional support in order to guarantee the long-term sustainability of the journals. However, although the adoption of the diamond open access model among these journals demonstrates a strong commitment to equitable knowledge dissemination, this structural openness does not automatically translate into greater visibility and scientific impact. As Fuchs & Sandoval (2013) demonstrate, diamond OA journals remain significantly underrepresented in major indexing systems such as Scopus and Web of Science, which limits their international visibility.

Regarding ethical issues, there is a widespread interest among journals in including this type of guidance within their policies, as evidenced by broad adherence to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). However, this commitment does not always translate into clear and consistent implementation. There are notable disparities in the requirements and presentation of information related to funding sources, conflicts of interest declarations, author contributions, and the dissemination of research data. While some journals provide detailed forms and specific guidelines for each of these elements, others merely mention them in a generic manner. This lack of consistency may undermine transparency, reproducibility, and trust in editorial processes. Therefore, it is recommended that these criteria be explicitly stated in the author guidelines documents.

In relation to emerging technological practices, the treatment of AI usage in the preparation and submission of manuscripts stands out as a particularly relevant and increasingly important issue in editorial policies (Kousha & Thelwall, 2024). Nevertheless, its presence in the journals analysed remains limited and uneven. Only a minority explicitly mention the use of generative AI tools, and among those that do, there is variation in where such information must be disclosed (e.g., within the manuscript, the methodological section, or in comments to the editor), as well as in the level of detail required. This lack of standardisation hampers a clear assessment of the level of technological transparency demanded from authors. Related to these issues, the widespread use of anti-plagiarism software is seen as a strength, reflecting concern for academic integrity (Hernández-Ruiz, 2016). A more consistent alignment with shared standards would be desirable to ensure the ethical and responsible use of such technologies in academic publishing.

The limited use of specialised social media compared to generalist platforms highlights the focus on dissemination, which, however, neglects the role of the former in building scientific communities (Mondragón del Ángel & Canchola-Magdaleno, 2024; Viera Savigne et al., 2024). Thus, increasing the presence on specialised social media can be a valuable tool for giving greater visibility to journals and the scientific output they publish.

Although there is a general commitment to developing a visual identity, significant disparities in its implementation may compromise both the communicative coherence and the ability of journals to position themselves within the scientific ecosystem. The widespread use of differentiated covers for each issue appears to reflect a strategy of personalization aimed at highlighting the uniqueness of each edition. This contributes to reinforcing the distinctive character of the publication and facilitates its identification by readers. Moreover, it can enhance the journal’s professional image and visibility across indexing platforms, academic social networks, and institutional repositories.

However, the lack of consistency in key graphic elements—such as logos, institutional seals, or visual marks—between the website and the PDF version reveals a weakness in integrated visual identity management. This inconsistency hinders cross-platform recognition and weakens the journal’s ability to establish a strong editorial brand. In the context of content saturation, visual coherence is essential to attract attention and retain audience engagement.

The same issue applies to typographic choices. While websites tend to use a limited and consistent set of fonts, the PDF versions show more variability, indicating the absence of unified editorial design policies. This type of fragmentation affects the aesthetic quality of the editorial product and its perception as a rigorous academic publication, reducing its potential impact on readers and prospective contributors. Font selection appears to be influenced by technical constraints of the publishing platforms, as evidenced by the high prevalence of the Noto font family, used in 67.85% of the sample (19 out of 28 journals).

In addition, the limited availability of flexible and editable templates forces editorial teams to carry out numerous manual adjustments, which increases the time and effort required during the production process. Improving visual and typographic coherence should be understood as a strategic action that directly enhances editorial efficiency, reader experience, institutional recognition, and the journal’s ability to project prestige, attract authors, and build audience loyalty.

5. Limitations and Further Lines of Research

While this study offers a detailed analysis of editorial policy, certain limitations present opportunities for future lines of research. Thus, by taking a comparative perspective and expanding the sample to other regions, parallels could be drawn between different publishing strategies aimed at adaptation to international assessment standards. In this regard, previous research has highlighted the usefulness of comparative approaches, an example of which is the study carried out by Beigel (2014) and Demeter et al. (2022). Similarly, broadening the scope of the sample to include other databases with a strong regional presence would provide a more representative view of the Latin American publishing ecosystem. This would be especially true regarding journals not indexed in Scopus or WoS, which is in line with studies such as those of Gonzalez-Pardo et al. (2020) and Uribe Tirado (2023).

Future research could employ interviews or questionnaires with editorial teams to gain more nuanced insights into the internal dynamics and strategic decisions of scientific journals. This type of approach, as previously undertaken by Fonseca-Mora et al. (2014), would offer direct access to the perspectives of those responsible for editorial management. In addition, it would help address one of the main limitations of the present study, which is its exclusive reliance on publicly available web content, by providing complementary first-hand information that is not accessible through online sources alone.

6. Conclusions

The inclusion of science journals in databases such as Scopus and Web of Science is a decisive factor for enhancing the visibility and international reach of academic research. Against this backdrop, the present study has examined the editorial policies of communication journals published in Latin America, which are indexed on these platforms. According to the findings, although the mere presence of these journals on these indexing systems implies being acknowledged as high-quality periodicals, there are still areas of improvement worthy of consideration. It should also be noted that indexation does not in itself resolve the structural limitations of the journals in terms of international academic exchange. This broader perspective, initially raised in the introduction, frames the relevance of assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the indexed journals analysed here.

The analysis carried out provides an overview of the current situation of these journals, confirming a certain degree of assumed compliance with editorial criteria due to their presence in Scopus and WoS. Likewise, it is advisable to go beyond the formal adherence to principles such as those recommended by COPE. This can be performed by displaying a specific statement of ethical commitments and practices aimed at transparency, which are key factors in reinforcing trust in editorial procedures.

The findings related to website functionality and the development of an editorial identity imply that action must be taken to enhance these areas. Improving these aspects will not only meet quality requirements but will also help to optimise the user experience and consolidate the role of these journals as effective vehicles for science communication.

Finally, the importance of institutional support has been underscored, especially in an environment where most of these journals operate by using the diamond model, which means they do not have direct monetary financing. Given the context, it is essential to recognise the commitment and work of the editorial teams, as they are the ones who are responsible for sustaining and developing these initiatives and for positioning themselves as key players in the region’s scientific ecosystem.

At the same time, the predominance of open access—particularly through the diamond model—invites reflection on its advantages and limitations in the Latin American context. While open access maximises the visibility and circulation of research without imposing costs on authors, it also faces challenges of financial sustainability and operational fragility. By contrast, publishing models with associated costs—whether based on subscriptions or APC—may provide greater economic stability, though often at the expense of accessibility and dissemination. This tension underscores the need to critically assess how open access can be further strengthened so that its benefits outweigh its limitations and contribute to the growth and international projection of Latin American scholarly publishing. In this scenario, the role of universities—the main publishing institutions in the region—is crucial for ensuring the continuity and consolidation of these journals. Therefore, the hybrid nature of the communication field presents an opportunity to foster inter-institutional collaboration that will strengthen the sustainability of the Latin American publishing system.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/publications13030039/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; methodology, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; software, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; validation, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; formal analysis, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; investigation, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; resources, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; data curation, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; visualisation, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; supervision, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M.; project administration, F.S.-P., M.B.-C., and B.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The translation was funded by the High-Performance Research Group INECO (Innovation, Education and Communication) at Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (URJC, Spain).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CC BY | Creative Commons Attribution |

| CC BY-NC | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial |

| CC BY-NC-ND | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives |

| CC BY-NC-SA | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike |

| CC BY-ND | Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives |

| COPE | Committee on Publication Ethics |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| EPUB | Electronic Publication |

| ESCI | Emerging Sources Citation Index |

| HTML | HyperText Markup Language |

| ISSN | International Standard Serial Number |

| JCR | Journal Citation Reports |

| OJS | Open Journal Systems |

| ORCID | Open Researcher and Contributor ID |

| Portable Document Format | |

| RedALyC | Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal |

| ROR | Research Organization Registry |

| SciELO | Scientific Electronic Library Online |

| SJR | SCImago Journal Rank |

| WoS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

The following appendix provides a list of the journals included in the study, indicating their publisher’s country as well as their inclusion in the Scopus and WoS databases.

Table A1.

Journals included in the study.

Table A1.

Journals included in the study.

| Journal | Country | Scopus | SJR | WoS | JIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social “Disertaciones” | Colombia | Yes | 0.133 | No | N/A |

| Austral Comunicación | Argentina | Yes | 0.130 | Yes | 0.1 |

| Brazilian Journalism Research | Brazil | Yes | 0.336 | Yes | 0.5 |

| Caracol | Brazil | Yes | 0.103 | No | N/A |

| Chasqui | Ecuador | No | N/A | Yes | 0.1 |

| Cogency | Chile | Yes | 0.124 | No | N/A |

| Comunicação, Mídia e Consumo | Brazil | Yes | 0.110 | No | N/A |

| Comunicación y Medios | Chile | Yes | 0.195 | Yes | 0.2 |

| Comunicación y Sociedad | Mexico | Yes | 0.237 | Yes | 0.4 |

| Contratexto | Peru | Yes | 0.209 | No | N/A |

| Cuadernos.info | Chile | Yes | 0.328 | Yes | 0.7 |

| Discursos Fotográficos | Brazil | Yes | 0.102 | No | N/A |

| Dixit | Uruguay | No | N/A | Yes | 0.2 |

| Estudios de Teoría Literaria | Argentina | Yes | 0.110 | No | N/A |

| Infodesign | Brazil | Yes | 0.186 | No | N/A |

| Informação & Sociedade | Brazil | Yes | 0.104 | No | N/A |

| Interface | Brazil | Yes | 0.298 | No | N/A |

| Palabra Clave | Colombia | Yes | 0.206 | Yes | 1.1 |

| Perspectivas de la Comunicación | Chile | No | N/A | Yes | 0.3 |

| Perspectivas em Ciencia da Informaçao | Brazil | Yes | 0.173 | No | N/A |

| Questión | Argentina | No | N/A | Yes | 0.1 |

| Revista Comunicação Midiática | Brazil | No | N/A | Yes | <0.1 |

| Revista de Comunicación | Peru | Yes | 0.362 | Yes | 1.3 |

| Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios del Discurso | Brazil | Yes | 0.126 | No | N/A |

| Revista Mediação | Brazil | No | N/A | Yes | <0.1 |

| Signo y Pensamiento | Colombia | Yes | 0.113 | No | N/A |

| Texto Livre | Brazil | Yes | 0.221 | No | N/A |

| Transinformação | Brazil | Yes | 0.208 | No | N/A |

Appendix B

The following appendix contains the coding system developed for data collection.

Table A2.

Coding system.

Table A2.

Coding system.

| Item | Response | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | ||

| ISSN | 0: does not have a DOI; 1: has a DOI | The ISSN is verified through the International ISSN Portal |

| DOI | 0: published in co-publication; 1: published in co-publication | DOIs are checked using the Resolve a DOI Name11 from the DOI Foundation |

| Co-publication | Indicate the type of entity that publishes the journal | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Type of entity | Indicate the type of secondary entity that publishes the journal | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Type of secondary entity | Indicate the name of the publisher | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed. When sufficient information is available, the dependent entity is indicated—for example, faculties or departments in the case of universities |

| Publisher | Indicate the name of the country | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Country | Indicate the publication frequency of the journal | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Publication frequency | Indicate the subject area(s) covered by the journal | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Subject area | Indicate the year the journal was founded | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Year of establishment | Indicate the type of entity that publishes the journal | The information published on the journal’s website and on Dialnet and Latindex is reviewed |

| Platform | ||

| Platform in Spanish | 0: the website does not have a Spanish version; 1: the website has a Spanish version | The website is reviewed |

| Platform in French | 0: the website does not have a French version; 1: the website has a French version | The website is reviewed |

| Platform in English | 0: the website does not have an English version; 1: the website has an English version | The website is reviewed |

| Platform in Italian | 0: the website does not have an Italian version; 1: the website has an Italian version | The website is reviewed |

| Platform in Portuguese | 0: the website does not have a Portuguese version; 1: the website has a Portuguese version | The website is reviewed |

| Articles in Spanish | 0: the journal does not accept articles in Spanish; 1: the journal accepts articles in Spanish | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Articles in French | 0: the journal does not accept articles in French; 1: the journal accepts articles in French | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Articles in English | 0: the journal does not accept articles in English; 1: the journal accepts articles in English | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Articles in Portuguese | 0: the journal does not accept articles in Portuguese; 1: the journal accepts articles in Portuguese | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Editorial manager | Indicate the editorial management software | The website and its code are reviewed |

| OJS version | Indicate the OJS version | If OJS is used, the website’s code is examined |

| OJS implementation year | Indicate the publication year of the OJS version | The date table published by the Public Knowledge Project is used as a reference |

| Web article | 0: no web version is available for each article; 1: a web version is available for each article | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| HTML article | 0: no HTML version is available for each article; 1: an HTML version is available for each article | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| PDF article | 0: no PDF version is available for each article; 1: a PDF version is available for each article | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| EPUB article | 0: no EPUB version is available for each article; 1: an EPUB version is available for each article | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Usage statistics | 0: article-level usage statistics are not provided; 1: article-level usage statistics are provided | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Impact metrics | 0: article-level impact metrics are not provided; 1: article-level impact metrics are provided | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Altmetrics | 0: article-level alternative metrics are not provided; 1: article-level alternative impact metrics are provided | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Tools (other) | 0: no other tools are provided; 1: other tools are provided | The article pages in the latest and penultimate issues are reviewed. If tools are found, this is noted in the observations |

| Visibility | ||

| Indexing information | 0: no information is provided about the journal’s indexing; 1: information is provided about the journal’s indexing | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| DOAJ | 0: the journal is not indexed in DOAJ; 1: the journal is indexed in DOAJ | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed and checked against DOAJ12 |

| Latindex | 0: the journal is not indexed in Latindex; 1: the journal is indexed in Latindex | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed and checked against Latindex13 |

| Dialnet | 0: the journal is not indexed in Dialnet; 1: the journal is indexed in Dialnet | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed and checked against Dialnet14 |

| Scopus/SJR | 0: the journal is not indexed in Scopus/SJR; 1: the journal is indexed in Scopus/SJR | Data obtained from the initial download in SJR |

| Scopus/SJR—year | Indicate the year in which it was included in Scopus/SJR | Data obtained from the initial download in SJR |

| Scopus/SJR—quartile | Indicate the quartile in SJR | Data obtained from the initial download in SJR |

| WoS/JCR | 0: the journal is not indexed in WoS/JCR; 1: the journal is indexed in WoS/JCR | Data obtained from the initial download in JCR |

| WoS/JCR—year | Indicate the year in which it was included in WoS/JCR | Data obtained from the initial download in JCR |

| WoS/JCR—quartile | Indicate the quartile in JCR | Data obtained from the initial download in JCR |

| WoS/JCR—index | Indicate the index in JCR | Data obtained from the initial download in JCR |

| Open access, ethics, and transparency | ||

| Open access | 0: the journal is not open access; 1: the journal is open access | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Open access route | Indicate the open access route under which the journal is published | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Licence | Indicate the licence under which the journal is published | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Preservation | 0: no information is provided about self-archiving and digital preservation; 1: information is provided about self-archiving and digital preservation | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Privacy | 0: no privacy statement is provided; 1: a privacy statement is provided | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Author identifier | 0: no author identifier is provided at the article level; 1: an author identifier is provided at the article level | The use of identifiers such as ORCID15 is verified. The article pages in the latest and penultimate issues and the PDF versions are reviewed |

| Institution identifier | 0: no institution identifier is provided at the article level; 1: an institution identifier is provided at the article level | The use of identifiers such as ROR16 is verified. The article pages in the latest and penultimate issues and the PDF versions are reviewed |

| Dates | Indicate the dates that are provided at the article level | The editorial process dates mentioned in the published article are identified (e.g., submission date, review date, acceptance date, etc.) |

| Ethical information | 0: no ethical information is provided; 1: ethical information is provided | The article pages in the latest and penultimate issues and the PDF versions are reviewed |

| COPE—member | 0: not a member of COPE; 1: member of COPE | The information published on the journal’s website and the COPE website17 is reviewed |

| COPE—principles | 0: does not adhere to COPE principles; 1: adheres to COPE principles | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Authorship | 0: author contribution statement is not required; 1: author contribution statement is required | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Data | 0: data sharing is not required; 1: data sharing is required | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Conflicts of interest | 0: disclosure of conflicts of interest is not required; 1: disclosure of conflicts of interest is required | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Funding | 0: disclosure of funding sources is not required; 1: disclosure of funding sources is required | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| AI-related information | 0: no information is provided regarding the use of AI; 1: information is provided regarding the use of AI | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Plagiarism detection software | 0: no information is provided about the use of plagiarism detection software; 1: information is provided about the use of plagiarism detection software | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Social media | ||

| Social media | 0: does not use social media; 1: uses social media | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed |

| Academia.edu | 0: does not have a profile on Academia.edu; 1: has a profile on Academia.edu | The information published on the journal’s website and on Academia.edu is reviewed |

| 0: does not have a profile on Facebook; 1: has a profile on Facebook | The information published on the journal’s website and on Facebook is reviewed | |

| 0: does not have a profile on Instagram; 1: has a profile on Instagram | The information published on the journal’s website and on Instagram is reviewed | |

| 0: does not have a profile on LinkedIn; 1: has a profile on LinkedIn | The information published on the journal’s website and on LinkedIn is reviewed | |

| ResearchGate | 0: does not have a profile on ResearchGate; 1: has a profile on ResearchGate | The information published on the journal’s website and on ResearchGate is reviewed |

| TikTok | 0: does not have a profile on TikTok; 1: has a profile on TikTok | The information published on the journal’s website and on Academia.edu is reviewed |

| 0: does not have a profile on WhatsApp; 1: has a profile on WhatsApp | The information published on the journal’s website and on WhatsApp is reviewed | |

| X (formerly Twitter) | 0: does not have a profile on X; 1: has a profile on X | The information published on the journal’s website and on X is reviewed |

| YouTube | 0: does not have a profile on YouTube; 1: has a profile on YouTube | The information published on the journal’s website and on YouTube is reviewed |

| Other social media | 0: no other social media are provided; 1: other social media are provided | The information published on the journal’s website is reviewed. If other social media are found, this is noted in the observations |

| Design and editorial identity | ||

| Cover page | 0: no cover is provided for each issue; 1: a cover is provided for each issue | The two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Graphic identity | 0: the journal does not have a graphic identity; 1: the journal has a graphic identity | The journal’s website is reviewed |

| Article-level graphic identity | 0: the graphic identity appears in the articles; 1: the graphic identity does not appear in the articles | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Colour scheme | Indicate the colour scheme using a hexadecimal code | The ColorZilla tool18 is used to obtain the hexadecimal code |

| Website layout type | Indicate the font type(s) used on the website | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed using the What the Font tool19 |

| PDF layout type | Indicate the font type(s) used in the PDF version of the articles | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed using Adobe Acrobat Pro |

| Typographic consistency | 0: no typographic consistency; 1: typographic consistency | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Typographic unity | 0: no typographic unity; 1: typographic unity | The article pages in the two most recent issues are reviewed |

| Graphic style | 0: no predefined graphic style is offered; 1: a predefined graphic style is offered | The journal’s website is reviewed |

| Template | 0: no article template is offered; 1: an article template is offered | The journal’s website is reviewed |

Notes

| 1 | The journal’s website indicates a change in publisher. We have reviewed the site, and the governing body is from the Czech Republic. |

| 2 | https://portal.issn.org/ (accessed on 13 April 2025). |

| 3 | This journal is jointly published by the Universidad del Rosario (Colombia), the Universidad de los Andes (Venezuela), and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain). |

| 4 | The first version of Open Journal Systems (OJS) appeared in 2001. |

| 5 | “Continuous publication” refers to the model in which articles are published individually throughout the year as soon as they are ready, without being grouped into discrete issues. “Biannual publication” refers to two issues per year (semiannual), and “triannual publication” refers to three issues per year. |

| 6 | Scopus and WoS use the term “Communication” to name the category. |

| 7 | https://www.gov.br/governodigital/pt-br/acessibilidade-e-usuario/vlibras (accessed on 11 April 2025). |

| 8 | For this study, the position in the communication category was used as a reference. |

| 9 | The ISSN is not a requirement for becoming a periodical publication, but it is a requirement for being included in various scientific information resources, such as the Scopus and WoS databases. |

| 10 | https://pkp.sfu.ca/software/ojs/download/archive/ (accessed on 11 April 2025). |

| 11 | https://dx.doi.org/ (accessed on 11 April 2025). |

| 12 | https://doaj.org/ (accessed on 13 April 2025). |

| 13 | https://www.latindex.org/ (accessed on 12 April 2025). |

| 14 | https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ (accessed on 10 April 2025). |

| 15 | https://orcid.org/ (accessed on 12 April 2025). |

| 16 | https://ror.org/ (accessed on 12 April 2025). |

| 17 | https://members.publicationethics.org/members (accessed on 10 April 2025). |

| 18 | https://www.colorzilla.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2025). |

| 19 | https://what-the-font.adsmediaextensions.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2025). |

References

- Aguado-Guadalupe, G., Herrero-Curiel, E., & de Oliveira Lucas, E. R. (2022). Dinámicas de la producción científica española en las revistas de comunicación en WoS. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 45(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-López, E., Becerril-García, A., & Godínez-Larios, S. (2024). Asociarse o perecer la colaboración funcional en las ciencias sociales latinoamericanas. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 161, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave-Cabrera, J., & González-Pardo, R. (2022). Investigación bibliométrica de comunicación en revistas científicas en América Latina (2009–2018). Comunicar, 30(70), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asubiaro, T., Onaolapo, S., & Mills, D. (2024). Regional disparities in Web of Science and Scopus journal coverage. Scientometrics, 129(3), 1469–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babini, D. (2019). La comunicación científica en América Latina es abierta, colaborativa y no comercial. Desafíos para las revistas. Palabra Clave, 8(2), e065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiget, T., & Torres-Salinas, D. (2013). Informe APEI sobre publicación en revistas científicas. Asociación Profesional de Especialistas en Información. Available online: https://www.apei.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/InformeAPEI-Publicacionescientificas.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Barranquero Carretero, A., & Ángel Botero, A. M. (2015). La producción académica sobre comunicación, desarrollo y cambio social en las revistas científicas de América Latina. Signo y Pensamiento, 34(67), 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, F. (2014). Publishing from the periphery: Structural heterogeneity and segmented circuits. The evaluation of scientific publications for tenure in Argentina’s CONICET. Current Sociology, 62(5), 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. (2024). Journal evaluation process and selection criteria. Clarivate. Available online: https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/web-of-science-core-collection/editorial-selection-process/journal-evaluation-process-selection-criteria/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- COPE. (2022). Principles of transparency and best practice in scholarly publishing. COPE; DOAJ; OASPA; WAME. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E., Torres-Salinas, D., & Roldán, A. (2007). El fraude en la ciencia: Reflexiones a partir del caso Hwang. Profesional de la Información, 16(2), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demeter, M., Goyanes, M., Navarro, F., Mihalik, J., & Mellado, C. (2022). Rethinking de-westernization in communication studies: The Ibero-American movement in international publishing. International Journal of Communication, 16, 3027–3046. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/18485 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Ekdale, B., Rinaldi, A., Ashfaquzzaman, M., Khanjani, M., Matanji, F., Stoldt, R., & Tully, M. (2022). Geographic disparities in knowledge production: A big data analysis of peer-reviewed communication publications from 1990 to 2019. International Journal of Communication, 16, 28. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/18386 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Elsevier. (2024). Content policy and selection. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/content/content-policy-and-selection (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Fernández-Quijada, D., Masip, P., & Bergillos, I. (2013). El precio de la internacionalidad: La dualidad en los patrones de publicación de los investigadores españoles en comunicación. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 36(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Mora, M. C., Tur-Viñes, V., & Gutiérrez-San Miguel, B. (2014). Ética y revistas científicas españolas de comunicación, educación y psicología: La percepción editora. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 37(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C., & Sandoval, M. (2013). The diamond model of open access publishing: Why policy makers, scholars, universities, libraries, labour unions and the publishing world need to take non-commercial, non-profit open access serious. TripleC: Communication. Capitalism & Critique, 11(2), 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Pardo, R., Repiso, R., & Arroyave-Cabrera, J. (2020). Revistas iberoamericanas de comunicación a través de las bases de datos Latindex, Dialnet, DOAJ, Scopus, AHCI, SSCI, REDIB, MIAR, ESCI y Google Scholar Metrics. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 43(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ruiz, A. (2016). La política editorial antifraude de las revistas científicas españolas e iberoamericanas del JCR en ciencias sociales. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 24(48), 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, A., Pujol-Cols, L., Bispo, M. de S., Gentilin, M., & Mongrut, S. (2024). Revistas académicas latinoamericanas: Relevancia, desafíos y estrategias de desarrollo. FACES. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales, 31, 64. Available online: https://eco.mdp.edu.ar/revistas/index.php/faces/article/view/245 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Kousha, K., & Thelwall, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence to support publishing and peer review: A summary and review. Learned Publishing, 37(1), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2002). Metodología de análisis de contenido. Teoría y práctica. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. (2021). Digital Object Identifier (DOI) and DOI services: An overview. Libri, 71(4), 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]