Abstract

This paper examines how journal-, article-, and author-related factors influence citation counts in the business field using 236 journal articles collected from an AACSB medium research output business school in the Middle East between 2017 and 2021. Results from association tests demonstrated that journal rank and format, the subfield of the article, and author prestige are significantly related to the number of citations. Results from CHAID further demonstrated the presence of an interaction/joint effect among variables; in particular: (1) articles published in Q1 WoS journals that are also authored/co-authored by prestige authors resulted in the highest number of citations; (2) articles published in Q2–Q3 WoS journals that also belonged to the business and management domain resulted in an average number of citations, and (3) articles published in Q4 or unranked journals in WoS also ranked Q3–Q4 or unranked in Scimago resulted in the lowest number of citations. These results provide theoretical implications and practical recommendations for faculty and business schools interested in enhancing their scholarly impact and rankings.

1. Introduction

The number of citations, which refers to the number of times a paper is cited by other papers, has become a key measure of scholarly performance in recent years for both individual faculty and institutions alike [1]. Faculty appointments, merit, and promotion decisions across most universities and institutional units are becoming increasingly contingent on the number of citations generated by individual faculty members as a measure of their scholarly productivity and impact [2,3], thus making citations a key success factor in today’s academic career path development. Additionally, most, if not all, university rankings used by major agencies and platforms (e.g., QS, Times Higher Education [THE]), whether at the overall institutional or the subject-matter level, including business and economics subjects or business school rankings, tend to be based at least partially on the average number of citations generated per faculty member or per paper from an institution. This further makes the number of citations of primary importance for the institution’s ranking and prestige in general and for business subject/school ranking in particular [4,5].

Additionally, many accreditation bodies increasingly rely on citations to gauge the intellectual contribution, scholarly impact, and visibility of their member/accredited institutions [6]. The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), which, in addition to the European Quality Improvement System (EQUIS), is one of the leading business school accreditation agencies worldwide, clearly requires in Standard 8 that institutions must demonstrate the impact of their scholarly activities, with citation counts mentioned as an example of evidencing the academic/scholarly impact of member institutions/business schools [7]. This further emphasizes the importance of citations in today’s academic realm and specifically in the business field [6].

Given the growing importance of citation counts and the number of citations in today’s academic practices, many studies across various fields, including business [8,9,10,11,12] have aimed to identify the factors that drive citations in their respective disciplines and specifically in the business context/subject. Most of these studies concur on the three groups or types of factors that can impact citations, i.e., journal-related, article-related, and author-related characteristics [6]. The former is largely associated with the characteristics of the publication venue, including the journal quality and the reputation of the publisher. Article-related is associated with the intrinsic characteristics of the article itself, including variables such as the novelty of the idea/research plot, the clarity of writing, the length of the article, and the number of references. Finally, author-related factors are associated with the characteristics of the author(s), including the number of authors and collaboration scheme, authors’ reputation, and authors’ country and institutional affiliation. To date, however, these studies still show two main limitations.

First, existing studies have focused on a specific domain or subfield of business rather than examining papers across a broad range of business topics or subfields. This includes Management, Operations Research, MIS, Marketing, and, more recently, Management Education [4,6,9,11,13,14]. In each of these studies, a selection of a limited number of journals (typically highly ranked journals) in the discipline under consideration is used to identify the articles that are further analyzed to comprehend the factors that affect the number of citations in this case [11]. As such, the results from these studies cannot be extrapolated to the entire business field in general. Additionally, the fact that the articles analyzed are all taken from highly ranked journals, each in their respective discipline, limits the possibility of upholding the effects of some of the variables that drive citations, such as journal ranking or quality. Accordingly, calls have been made in recent years [3,6] for the need to start with a collection of articles published by a selected pool of business faculty members rather than specific journals or subfields and examine which of these articles are most likely to be cited based on the determinants or predictors identified in the literature. This would allow for better testing for all the predictors of citations (namely, the ranking or quality of the journal in which the article is published) while also expanding the analysis to different subfields and domains of business articles/journals, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of citation counts and the number of citations across the business subject/field.

Second, most, if not all, of the studies have relied primarily on association and regression techniques to examine how the different predictor variables considered in these studies affect citation counts in the considered articles/journals [4,6,9,11,14]. These former techniques are useful to single out the significance of each of the above-mentioned predictors and understand how each of these predictors influences the number of citations. However, they do not allow for testing or understanding how different predictors interact in determining the prospective number of citations for an article, as doing so would require performing a two-by-two or even higher level of interactions between every pair or multiple variables in the analysis/regression model. This would render the analysis very complex and cumbersome [15,16]. Accordingly, advanced forms of multivariate analysis techniques are required in order to examine how the different predictor variables identified in those previous papers work or combine together in predicting citation counts in the business subject or field specifically. For example, to understand if an economics article published in a highly-ranked journal by a low-prestige author is more likely to generate higher citations than a finance article published in a mid-ranked journal by high-prestige authors.

Given the gaps outlined above, this study will collect and analyze journal articles published by full-time tenure-track faculty at the Adnan Kassar School of Business (AKSOB) at the Lebanese American University between 2017 and 2021. AKSOB is an AACSB medium research output institution currently ranked in the top 351–400 and 301–400 in the subject of “business and management” and “business and economics” in QS and THE, respectively. It comprises six departments that touch upon all the subfields of business: economics, accounting and finance, marketing, management, information technology and operation management, and hospitality and tourism. This makes AKSOB a representative example to study as the papers included in our sample are expected to cover the different subfields in business and span across different types and levels of journals. This is as opposed to considering a top research business school whose faculty publish only in top journals, thus preventing testing how journal ranking or prestige might impact citation counts. Moreover, AKSOB, being AACSB accredited and showcasing in major business subject rankings, serves as a stand-in for many of the business schools worldwide that are also AACSB accredited and wished to maintain their accreditation and improve their positioning in the ranking game through enhancing the scholarly impact and citations of their research output and publications.

The selected papers in this study will be analyzed based on three groups or types of citation prediction variables, as mentioned earlier and as will be discussed in detail next in the literature section, namely journal-related, article-related, and author-related characteristics/variables. Association techniques and Chi-square automatic interaction detection (CHAID) analysis are used to examine the relationships between these variables and the number of citations received by a paper. The former will help obtain a sense of the significant association between each of the predictors and citation counts/number of citations, while the latter will serve to further corroborate and expand on the previous findings by highlighting how those significant associations interact in determining citation counts. CHAID follows a decision tree approach starting from our initial sample of papers (initial node), further splitting/branching out the initial sample in terms of the criterion variable or variable of interest, which in this case is the number of citations, into additional sub-samples (sub-nodes) based on the predictor variables (i.e., the three groups of variables mentioned earlier). The most significant predictor (splitting) variable will be used to come up with the first-level sub-nodes, followed by the second most significant variable to further split up those first-level sub-nodes into second-level sub-nodes, and so on until the process of node formation ends when there are no more significant relations between the number of citations and the remaining predictor variables [17,18]. In this way, CHAID works in a similar fashion as regression analysis in that it uses the different predictor variables to make predictions about the number of citations, except that it allows for the detection of interaction between the variables while doing that [19], which makes it more suitable in the context of this study.

In doing so, the present study provides theoretical implications in examining how different predictors of business citations interact to explain the number of citations across business in general rather than in one specific sub-discipline, whereas again, existing papers thus far have only looked at the direct effect of these variables on citations and have been limited to only a handful of top journals in one specific domain/subfield of business. Thus, our study helps expand our understanding of and shed more light on the drivers of citation counts in the business field in general. It also provides practical implications by providing guidelines and recommendations for medium-level business schools in general and their faculty in terms of how they can improve the number of citations from their prospective publications and subsequently enhance their career paths (for individual faculty members) as well as scholarly impact and standing when it comes to both accreditations and ranking (for schools).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Citation Prediction Studies in the Business Literature

Judge et al. [4] were among the first to examine citation predictors in business, more specifically in the management subfield. Using articles published in what the authors [4] identified to be the top journals in management (which totaled 21 in this case) over a five-year period (1990–1994), they found that the most significant variable affecting the number of citations was the journal prestige in terms of the journal impact factor (IF), followed by the number of references included in a paper, then the paper content; more specifically, the paper’s novelty measured in terms of the extent to which a paper introduced a novel idea or built on an existing idea (as opposed to refining an existing one); and finally, the prestige of the authors and the authors’ institution. The former was measured in terms of the highest number of total papers published in the top 21 journals identified earlier by any of the authors on a paper; the latter was calculated on a scale from 1 to 5 based on the Gourman Report quality rating of US universities with the score for the author at the highest rated school in each article was used. While the advantage of the Gourman Report, in this case, is its comprehensiveness, “as the U.S. News and QS World Report annual surveys—do not rate virtually every university, as does the Gourman Report” [4]; however, it does not include universities outside the US—in this case, a midpoint rating of 3 was assigned for international universities’ prestige—which is considered the main limitation of Judge et al.’s study.

More recent studies have been conducted across other business disciplines while expanding on Judge et al.’s [4] determinants and identifying three types or levels of citation predictors: journal-, article-, and author-related characteristics or variables [4,6,9,11]. For instance, in the operations/management science subfield, Mingers and Xu [9] examined the number of citations across six operations journals over one year (1990). The journals selected represented different status levels and qualities to be able to account for the effect of the journal choice on citations. The results, in this case, revealed that the strongest citation predictor is the journal itself, with papers published in Management Science, European Journal of Operations Research, and Operations Research yielding the most citations; the second strongest predictor was paper-related, with theoretical and empirical papers generating more citations than other types of papers, i.e., case study and viewpoint papers. One explanation for this is that theoretical and empirical papers, in this case, can be perceived as more novel, including new or expanding on existing ideas as compared to the latter (case study and viewpoints); and lastly, the number of pages (which is another article-related variable) was also found to affect citations but to a lesser extent than the former two variables. However, unlike Judge et al. [4], Mingers and Xu [9] found that author prestige (measured in terms of the number of publications of the first or sole author on a paper), institutional prestige (recorded in terms of the Times Higher Education (THE) rank also of the institution of the first or sole author), as well as the regional affiliation of the first/sole author (summarized in three groups: US, UK, and the rest of the world), did not have an effect on citation prediction. Regional affiliation in Mingers and Xu’s paper would serve as another proxy for institution prestige in this case.

Grover et al. [2] examined the determinants of citations in management and information system (MIS) papers published in the three most prominent journals in the subfield in terms of their impact factor over the period of 1990–2008. Their choice to limit their study to those three MIS journals was to control for the influence of journal quality on citation counts, with the results revealing that author-related variables, namely author prestige/recognition, measured in this case in terms of the h-index of the highly cited author on a paper were the strongest predictor of citation, followed by the article-related variable of the number of references, which in this case was used instead of the number of pages as longer papers tend to include more information and eventually more references; and finally, the novelty of the paper was once again a significant predictor of citation counts [2].

Similar to Grover et al. [2], Stremersch et al. [11] examined the number of citations across papers published between the period of 1990 and 2002 in the most prominent marketing journals this time, where again the choice of only top journals in the marketing subfield in terms of their impact factor limited the influence of journal quality and ranking on citation counts. However, unlike the aforementioned studies, Stremersch et al. [11] used awards as well as the subject area (identifying 19 trendy subject areas in marketing, in this case) as a substitute for paper novelty when examining the influence of paper-related variables on citations in their respective study, with their results revealing that author-related variables of author’s prestige and school’s ranking measured in terms of the number of publications of the most published author in the top-three marketing journals considered above, as well as the average school ranking in Financial Times across all authors of an article, had the strongest influence on citation counts; this was followed by subject area with topics such as relationship marketing, e-commerce, and service quality exerting a significant positive impact on citations; and lastly, awards earning and paper length were also significant to a lesser extent in this case. Worth noting as well that Stremersch et al. [11] and, unlike Grover et al. [2], did not consider the number of references, instead using paper length (number of pages) as a substitute for the former in their study.

Lastly and most recently, Hwang et al. [6] examined citation predictions in the even more narrow subfield of management education. Using articles published in seven such journals identified by the authors [6] over a five-year period from 2006–2010, the results obtained revealed that the number of references was the only significant article-related variable in this case and the strongest predictor of citation counts among all considered variables. The number of references acted as a proxy for the quality/novelty of and the amount of information included in an article in this case. The second strongest predictor was the journal prestige measured in terms of the journal’s h-index. Moreover, finally, author-related variables of author prestige and author affiliation prestige were also significant, albeit to a lesser extent, with the former measured in terms of the h-index of the highest cited author on a paper while the latter was gauged using a citation-based measure for the institution/affiliation prestige of the first author. Worth noting that among the variables that were found to be non-significant in Hwang et al.’s study was the number of co-authors and the regional affiliation of the first author. The non-significant effect of the former (number of authors) was most likely proxied for by the author prestige/h-index of the most cited author, as having more authors on a paper will eventually increase the possibility of achieving a higher authors prestige or h-index through the extra number of people who are involved. The latter (regional affiliation) was most likely substituted for by the effect of institutional prestige, as most reputed universities are often located in the western part of the world [6].

2.2. Choice of Citation Predictor Variables

Based on the above review, journal-, article-, and author-related variables were also used in the present study to examine the determinants of citation counts across the entire business field.

More specifically, three variables were used to measure journal characteristics, namely Scimago quartiles rank and WoS quartiles rank, as well as publication format, that is, whether the journal is open or closed access. Quartiles rather than journal impact factors (IF) or h-index were used to measure journal prestige as quartiles provide a more standardized way to compare journals across different business subfields. Journals in different subfields might exhibit different circulation and reach and might thus vary in terms of their citation behavior and their h-index/IF, making them a less credible measure [3,20]. Additionally, quartiles tend to be more static over time compared to the h-index and impact factor, as they often change from year to year [6]. As such, knowing that our sample of articles in this study was collected over a five-year period, the use of quartiles would also ensure consistency in the way we measure journal quality and prestige over time. Finally, both Scimago and WoS ranks were used in this case, as previous studies [21] have shown discrepancies in the quartiles’ ranking of journals across both listings. So using both measures would ensure a more comprehensive representation of journals’ ranking and, ultimately, better results in terms of understanding the effect of journal prestige on business citation counts. Journal ranking, again, is considered to be a key driver of citation counts in general and in business in specific, whereas top-ranked or top-quartile journals are known for their challenging review process and often incur a high desk rejection rate. Thus, publishing in such journals can add credibility to a paper, and citing such papers would, in turn, add credibility to the citing paper and might eventually lead to higher citations [12]. The publication format again relates to whether a journal is published open or closed access. While the format of publication of a journal was not examined in the business literature, there is strong evidence in other fields, particularly medicine, science, and engineering, that papers published in open-access journals are cited more often than those published in non-open access due to the visibility and accessibility of research [22]. In the business field, one could counter-argue that most of the open-access journals are usually low-ranked or low-quartile [23,24], but this positive spillover on the number of citations might be wired out by the low credibility and the status of the business journal in this case. Thus, incorporating this latter variable in our study will help shed further light on that regard.

Two variables were used to measure article characteristics: article length, which refers to the article’s number of pages, and the business domain or subfield of an article. Article length is believed to be a proxy of article quality, in particular in the social sciences and business fields, where longer articles tend to be the norm for many journals and publishers [6]. Extensive articles tend to incorporate complete information about a topic, more novel ideas, and more supporting evidence in terms of tables, figures, references, and appendices. This adds to the credibility of a published manuscript and, subsequently, the likelihood of that manuscript being cited [11,25]. As for the business domain, different domains or subfields of a paper may engender different citation behavior and citation counts depending on the number of journals available in each subfield, the volume of papers published within different subfields, and the scope of topics and subject areas that might be included. Evidence suggests that smaller fields that touch on limited topics tend to include fewer citations than more extensive and general fields [3,26]. In this study, we classified journals across three broad domains: business and management, economics and econometrics, and interdisciplinary papers. On the one hand, this simple categorization was used to keep the analysis simple in light of the broad range of topics covered in our sample (see Appendix A Table A1); on the other, the former two categories were adopted by Scimago for their grouping of scientific publications by subject area with business and management encompassing the different topics within business, such as MIS, Accounting, Operations, Marketing, Management, and Hospitality and Tourism, except for economics, while economics and econometrics were mainly limited to economics topics (https://www.scimagojr.com/ (accessed on 3 August 2022)). This is also more or less the same grouping used by QS and THE subject ranking, with business and management set apart from economics (i.e., in QS) and with the former encompassing all of the topics mentioned above. The third category (interdisciplinary) was used to categorize all other papers outside the business and economics topics intertwined with other fields, such as environment, energy, health, and transportation.

Lastly, four variables were used to measure author characteristics: author’s prestige and regional affiliation, number of authors, and international collaboration. Author prestige was measured in terms of the h-index of the most cited author/co-author on a paper, which represents a better measure of scholarly reputation than merely the number of papers or number of citations. h-index combines productivity (number of papers produced) and impact (number of citations) together in a single number, with both productivity and impact required for a high h-index. Neither a few highly cited papers nor a long list of papers with only a handful of citations will yield a high h-index [2,27]. Evidence shows that publications written by well-known authors who have achieved prominence and prestige in their field of study tend to be considered more credible sources by other authors; as such, prestigious authors tend to achieve more readability for and citations from their publications than the less prestigious ones [2,3]. Furthermore, regional affiliation was measured in terms of the geographic region where the first author or first author’s institution is based. It is a common understanding that some regions are privileged with adequate financial support, and therefore, institutions in those regions profit from generating better and more credible research [28,29]. Thus, regional affiliation served in this case as a stand-in for institutional prestige and is categorized in this study into eight groups or regions: Middle East, Africa, Asia/Pacific, Western Europe, Central Europe, North America, and Latin America. This closely replicates the geographic grouping used by the Scimago website to categorize the regional affiliation of the different journals listed in its database (see https://www.scimagojr.com/ (accessed on 3 August 2022)). Additionally, only the regional affiliation of the first author was used, as it is the best way to characterize an article’s author profile, given that in the business subject, the first author is the one who usually initiates and commits to the most research effort into an article [6]. Finally, the number of co-authors was simply the total number of authors listed on a paper. International collaboration refers to having at least one of the authors affiliated with an institution outside of Lebanon, as again, the context of this study is from faculty at the Lebanese American University. This, along with evidence, in this case, supporting the fact that papers that involve more authors, as well as international collaboration among authors from different countries, tend to have greater quality and credibility. Consequently, this tends to achieve greater impact and citation behavior [1], which makes the use of these two variables in this case further justified.

Accordingly and based on the above review, the present paper aims to examine and answer the following research questions:

RQ1: Which of the above nine variables relating to journal, author, and article characteristics are significantly associated with business citation counts?

RQ2: How do the above variables interact or work together in influencing citation counts in the business field?

RQ3: How can business faculty and, in general, business schools use the results from the above two questions to improve the number of citations from their prospective publications and to enhance their scholarly impact and ranking, respectively?

3. Methodology and Sample

The papers used in the present study were collected from full-time tenure track faculty at the Adnan Kassar School of Business (AKSOB) at the Lebanese American University between 2017 and 2021. In this case, the five-year time period allowed adequate time for published articles to develop citation patterns, with other studies also adopting similar approach (i.e., using a five-year period for analyzing citation counts; see [6]). Moreover, although the present study was written in August 2022, we stopped our analysis in 2021 as the latest papers published in 2022 do not permit an ample time horizon to generate sufficient citations to be included in the present study (see [11] for similar reasoning). Google Scholar and Harzing Publish or Perish software (the latter for when faculty did not have a Google Scholar profile, which was quite rare) were used to identify and build our dataset, whereas only theoretical and empirical journal articles were retained in this case. We, therefore, removed any conference papers, books, and book chapters, as well as viewpoint, book review, and case study documents, in order to control the influence that the different types of publications might have on citation counts and, subsequently, curb any possible bias in our analysis. This is due to the fact that most conference papers, case studies, and textbooks were not listed in Scimago and WoS, while viewpoints and book reviews generated very low citations in this case, and with similar screening procedure suggested and used by previous citation prediction studies as well [2,9].

All papers were then analyzed in terms of the nine predictor variables introduced earlier as well as in terms of their citation counts/number of citations. More specifically, Scimago and WOS quartiles’ ranks were extracted from the most recent listings (published in 2022 for 2021) in both platforms, whereas Scimago was accessed freely through their website, and WoS was accessed through the Lebanese American University paid subscription. Publication format (open or closed access) was determined by visiting the journal website to verify whether the journal charges authors for mandatory article publication fee (APF) with all the journal articles freely available. Article length or number of pages was derived directly from the article’s first page, while the business subfield or domain was extracted from Scimago website by inspecting the subject area(s) assigned to each journal. If the journal belonged to business and management subject area, it was assigned to this former (business and management), regardless of the subject category in which it was further clustered (for e.g., marketing, hospitality, finance, HR, Strategy and MIS). The same reasoning was applied for economics and econometrics; only when a journal belonged to both subject areas: business and management, as well as economics and econometrics in Scimago, we further analyzed the title of the article and checked whether that faculty belonged to the economics department or non-economics department at AKSOB to decide how to list that article (again, as either Business and Management or Economics and Econometrics). Lastly, if the article belonged to any subject area other than Business and Management and Economics and Econometrics, it was listed as interdisciplinary. Furthermore, the number of authors, the regional affiliation of the first author, and international collaboration were also determined from the information available on the article’s first page, while the h-index of the highly cited author was derived from Google Scholar (or Harzing Publish or Perish when an author could not be located on Google Scholar) by looking up each author and co-author on every article and using the h-index metrics of the highly cited author in this case. Lastly, citation counts or the number of citations for each article was derived from Harzing Publish or Perish using per-year citation (i.e., average annual citation) rather than total cites to adjust for the time period in this case, given that earlier papers tend to generate more cumulative citations than more recent ones; this would allow us to compare article citations on equal grounds with previous papers using similar procedures for accounting for time period [6,11].

In total, 236 theoretical and empirical papers were identified and used for the present study (see Appendix A Table A1 for a full listing of the papers for indicative purposes). Moreover, Table 1 provides summary statistics of the full sample (all 236 articles) in terms of the nine predictor variables considered in this study as well as their citation counts (average annual citations). Out of the 236 papers, 8% (N = 18) were open access as opposed to 92% (N = 218) non-open access. Moreover, 50% (N = 119) were published in Q1 journals in Scimago as opposed to 28% (N = 66) in Q1 journals in WoS. On the other extreme, 6% (N = 14) were unranked in Scimago as opposed to 37% (N = 87) unranked in WoS. The average length of all articles was 17 pages with a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 55 pages, and 73% (N = 171) of the papers were in the domain of business and management, 12% (N = 28) in economics and econometrics, while 16% (N = 37) were interdisciplinary. The average number of authors on each paper was 3, ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 20, with 52% (N = 123) involving international collaboration. Lastly, in 81% of the papers (N =192) the regional affiliation of the first author was the Middle East, followed by North America (8% or N = 19). For the remaining 11% (N = 25), it was almost equally split between Western Europe and Asia/Pacific. The average h-index of the most cited author/co-author on each paper was 21, with a minimum of 3 and a maximum h-index score of 84.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

4. Analysis of Results

4.1. Results from Association Tests

Association tests, specifically, Spearman correlation, Kruskal–Wallis, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Mann–Whitney U, and independent t-tests [15] were first used in SPSS v. 26 [30] to examine the relationship among each of the nine predictor variables considered in this study as well as the number of citations (again measured per year or as the average annual citation received by each paper in our sample).

More specifically for the journal-related variables (Table 2), results of the Mann–Whitney U test revealed that publication format is significantly associated with citation (Z = −3.712; p < 0.05) with open access journals in this case showing fewer citations compared to non-open access ones. Likewise, results of the Kruskal–Wallis tests also revealed a significant association between each of the Scimago and WOS quartiles’ rank and citation counts (Kruskal–Wallis H = 51.371; p < 0.05 and Kruskal–Wallis H = 66.665; p < 0.05, respectively). In particular, papers published in Q1 journals in Scimago generated significantly higher citations than the ones published in other quartiles (Q2 down to unranked). Papers published in Q2 journals in Scimago generated higher citations than those published in their lower Scimago counterparts (Q3 and below) and those that were unranked. As for all other papers published in Scimago (Q3 and Q4) and the unranked ones, they yielded the same number of citations with no advantage in this case for those published in Q3 compared to Q4 or unranked. As for the WoS, only papers published in Q1 generated higher citation counts compared to their lower-ranked counterparts (papers published in Q2, Q3, and Q4 in WoS or unraked ones), with the latter showing no differences among each other when it came to the number of citations (see Table 2). It is worth noting that Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis were used because at least one of the groups in the above-mentioned variables (i.e., publication format and Scimago and WoS rank) had less than 20 observations, thus helping overcome the small-sample-size issue for these groups and producing more reliable and robust significance scores in this case [15].

Table 2.

Results of association tests between journal-related variables and number of citations.

For article-related variables (Table 3), Spearman and ANOVA test results revealed that paper length or the number of pages is not significantly associated with citation counts, while the business domain or the subfield to which the article belongs is significantly associated (F = 5.355; p < 0.05). ANOVA post-hoc test results further showed that articles published in Business and Management generated a significantly higher number of citations compared to those in economics and econometrics or interdisciplinary papers, with these last two categories showing no significant difference in terms of citations (see Table 3). The Spearman rather than the Pearson test was used to test for the relationship between paper length and the number of citations, as this former (Spearman) is more robust to possible deviations in normality with the number of citations variable in this case exhibiting large (>3 in absolute value) skewness and kurtosis scores (see Table 1).

Table 3.

Results of association tests between article-related variables and number of citations.

As for author-related variables (Table 4), results from Spearman and Kruskal–Wallis, in addition to the independent t-test, revealed that author prestige was the only variable that was significantly associated with the numbers of citations (Spearman’s r = 0.397; p < 0.05), suggesting that the higher the h-index of the most cited author on an article is, the higher is the number of citations; regional affiliation of the first author, number of authors, and international collaboration showed no significant associations with citations in this case. Again, the reason for using Kruskal–Wallis and Spearman, in this case, was the small size (N < 20) for some of the groups under regional affiliation as well as the most likely deviation from normality for the number of citations variable implied from its high skewness and kurtosis scores, respectively (Table 1).

Table 4.

Results of association tests between author-related variables and number of citations.

4.2. Results from CHAID Analysis

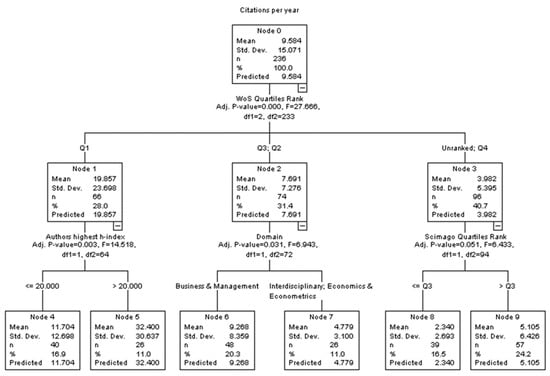

Finally, Chi-square automatic interaction detection (CHAID) was also performed in SPSS v.26 to further examine how those different prediction variables (more specifically, the ones that were found to be significant) interact or work together in predicting and determining citation counts. Again, CHAID allowed for splitting or branching out our initial sample of 236 papers into different sub-nodes in terms of citation counts (which is the criterion/dependent or variable of interest in this case), based on the most significant (i.e., strongest) predictor down to the least significant one, with the branching eventually stopping when no further significant predictors could be identified [19]. In this case, the stopping criteria for the CHAID analysis in SPSS were set at 50 observations for parent nodes (before the division of any (sub)sample) and 20 for child nodes (after the division of any (sub)sample) while the alpha significance level for predictor eligibility for splitting nodes was set at 10%; these two criteria allowed us to achieve an optimal branching (i.e., the maximum number of significant nodes), given our relatively small sample size, while ensuring no node has fewer than 20 observations, as to ensure representation and actionability for each node in this case [17,18]. Figure 1 shows the results from the CHAID analysis with the model/tree yielding an R-square of 0.672, meaning that 67.2% of the times or 67.2% of the variability in the citations can be explained by the CHAID analysis, where in particular:

Figure 1.

Results of CHAID analysis with all nodes splitting significantly at p ≤ 0.05.

- ₋

- The first node, or split, revealed that WoS quartiles rank is the best predictor of citation counts in this case, with papers published in Q1 journals in WoS generating on average 19.9 citations per year as opposed to 7.7 and 4 citations for those ranked Q2–Q3 and Q4-unranked in WoS, respectively;

- ₋

- The second node or split further revealed that: (1) for papers published in Q1 WoS, the next best predictor or splitting criteria, in this case, is the author’s reputation, whereas Q1 papers with one of the authors having h-index > 20 resulted in roughly 32.4 citations per year on average as opposed to 11.7 citations for the same Q1 papers when all authors had h-index ≤ 20. Conversely, (2) for Q2–Q3 papers in WoS, the next best predictor was the domain or subfield to which the article belonged, where the same Q2 or Q3 paper generated 9.3 citations per year on average if it were in the business and management domain as opposed to 4.8 if it were in economics and econometrics or an interdisciplinary paper. Lastly, (3) for Q4-unranked papers in WoS, the next best predictor was the Scimago quartiles rank, but Q4 or unranked papers in WoS that are ranked Q2 or Q1 in Scimago generated an average of 5.1 citations as opposed to 2.3 if they were ranked Q3 or below or unranked in Scimago (see Figure 1).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

The present paper aimed to enhance our understanding of the factors that affect citation counts/the number of citations in the business field by using 236 journal articles published by faculty at the Adnan Kassar School of Business between 2017 and 2021. The articles were analyzed using association tests and CHAID analysis according to nine citation predictor variables identified from the previous literature that relate to the characteristics of the journal where the article was published, the characteristics of the article itself, as well as the characteristics of the author(s) of the article. The purpose is to determine the extent to which each of these predictors is associated with citation counts among the selected articles, but most importantly, to determine how those different predictors interact or work together in influencing citation counts. In doing so, the results from the present study provide both theoretical and practical implications.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, the results first confirmed the significant relationship between journal rank and the number of citations received by a business paper. These results were further expanded and built on limited findings with regard to journal rank from previous citation papers in the business literature [6,9,11]. These were confined to only a few top journals within a specific subfield or domain in business (e.g., marketing, management, MIS), thus failing to examine the effect of journal rank on citation counts properly. Stremersch et al. [11] and Grover et al. [2], in their review of marketing and MIS articles, respectively, considered only the top-five marketing and top-three MIS journals in their analyses and did not examine for the effect of journal rank in this case. On the other hand, while Judge et al. [4] expanded their sample/analysis to include the top-21 management journals, they did not examine their quartile rank (as they were most likely all top quartile or Q1 in this case), so they used journal h-index as a proxy for journal rank or prestige, which is known to be dynamic. This challenges the longevity and robustness of their findings with respect to the relationship between journal h-index (as a proxy for journal prestige) and citations. Again, in this specific case, we established two findings. First, we were able to establish that Scimago and WoS quartiles rank are better measures of journal rank and prestige as they are more stable and represent a standardized way to compare business journals across time and domains. Second, we also confirmed the significant influence that these two ranks (Scimago and WoS) exert on citation counts across our sample of papers collected from different business domains, further extrapolating these results to the entire business field.

Results also upheld the significant relationship between author prestige, business domain, and publication format on one hand and citation counts on the other hand. Regarding author prestige, while the influence this has on the number of citations has already been confirmed in all of the previous studies [4,6,9,11], this has been performed within one specific business domain or subfield. The current findings are important in further demonstrating that author prestige is not constrained to one specific domain but rather spans the entire business subject. The prominence and reputation of the authors on a business paper, in general, can add to the credibility of that paper and to that paper being cited more frequently, especially given the intertwinement that exists between many of the business sub-disciplines. It is not, therefore, uncommon for a paper in one domain of business (e.g., marketing) to be cited by a paper in another domain (e.g., management or MIS) [11,25]. The results on the significant link found between the business domain and citation counts in the present study clearly revealed that papers published in business and management (including all topics/subject areas in business, e.g., marketing, management, accounting, MIS, and hospitality, except for economics) are more likely to generate higher citations than those published in economics and econometrics or interdisciplinary ones. All of the previously reviewed studies on business citations have failed to investigate and capture this type of relationship, given that each of these papers was conducted within one specific subfield. A plausible explanation for our results could be again the intertwinement between the various business and management topics leading to citations in one field being cited in another to achieve a higher level of circulation and reach. Economics, on the other hand, is less linked to typical business topics, with economics departments often housed separately from a business school (e.g., in the school of arts and science), as such they tend to receive fewer cross-citations or citations compared to papers published in business and management. Another plausible explanation as to why interdisciplinary papers receive fewer citations than business and management papers has to do with credibility: while previous studies have argued that people who publish on interdisciplinary topics or in interdisciplinary journals are usually less well-versed in other fields than in their own, their work can be regarded as less credible by scholars in the interdisciplinary field [3].

The significant relationship found between publication format (whether the journal is open access) and citations have not been tested or examined before in existing citation papers in the social sciences in general and in business specifically. This could be because with the exception of the MDPI open publisher, which has launched many business journals in recent years, open-access journals are not as common in the social sciences and business as they are in other fields such as medicine and science, and the few existing open-access journals in social sciences and business tend to fall under the stigma of predatory journals. Additionally, social science and business researchers typically do not have the funding support that their medicine and their sciences counterpart enjoy to pay open access fees, further explaining why this variable has received little attention in the social sciences and the business literature specifically. However, the present study has also demonstrated that open-access journals in business received fewer citations than their closed-access counterparts. While this can be counterintuitive, many studies in medicine, science and engineering have demonstrated the opposite [11,22,23]. One plausible explanation could be related to the issue of credibility. Given the current weak adoption and proliferation of open-access model/journals in business, with most of the current open-access journals (again, except for MDPI) being relatively lower ranked, scholars tend to restrain from citing open-access papers in their studies. This explains the low number of citations found for open-access journals in our study. It is also worth noting that we found the publication format as not significant in the results from the CHAID analysis. This is because only 18 papers in our sample were open access, which was not enough to generate or produce an additional sub-node, as a minimum of 20 papers was selected as the splitting criteria in our analysis. As the business field evolves, it would be interesting to retest publication type/open access again in future research to see how the perception of open-access journals in the business field and its implications for citation prediction and count might change in the future.

Lastly and most importantly, our results further revealed the existence of an interaction/joint effect in the way the different predictor variables used in this study influence citation counts and the number of citations in the business field, clearly showing that journal ranking, more specifically the WoS quartiles rank, need to be combined with author prestige, business domain, and Scimago quartiles rank to better understand the prospect for a given paper to generate and achieve high citations. In particular, results from the present study demonstrated that among Q1 papers in WoS, those that also included an author with a high prestige or h-index > 20 generated the highest number of citations per year (32.4). On the other hand, among Q2–Q3 papers in WoS, those belonging to the field of business and management generated the highest number of citations per year (9.3). Lastly, among Q4-unranked WoS papers, those that were concurrently ranked Q1–Q2 in Scimago were associated with the highest number of citations (5.1). These results highlight the need for further citation studies in general and in the business field, in particular, to start examining interaction effects when examining prediction citations, as this can allow a better understanding of the complexity of the citation mechanism and provide greater comprehension of citation prediction and count in the business field.

5.2. Practical Implications

In addition to the above theoretical implications, results from the present study can also be used to provide practical implications and guidelines for faculty and business schools in general and for medium research output business schools and their faculty, especially on how to improve their citations. This helps enhance their career paths (for individual faculty) and their institutional ranking (for business schools). In particular, based on the results from the present study, the first recommendation for business faculty, in general, and in medium business schools, in particular, would be to aim for Q1 papers in WoS while at the same time ensuring to have at least one author with an h-index greater than 20. The combination of these two criteria was shown to generate the highest number of citations per year (32.4). In this case, one way for faculty whose h-index falls below that threshold (20) to meet the above recommendation would be through collaboration by initiating or further nurturing their collaboration network by way of inviting other scholars on their papers or working on papers of other scholars. In this case, it does not matter if these scholars are colleagues at the same institution or even country, as regional affiliations were found not to affect citations, provided the scholars are well-established and -recognized (have an h-index > 20) within the business field.

The second recommendation would be that if faculty cannot publish in WoS Q1 journals and must instead publish in Q2–Q3 journals in WoS, they should avoid interdisciplinary papers and instead target Q2 or Q3 WoS journals that are in the business and management domain, which were shown to yield the highest citation counts per year among WoS journals (9.3). For faculty in economics, their best option is to go after Q1 in WoS. They could also try to publish in WOS Q2–Q3 Business and Management rather than economics journals, given that the former (business and management journals) seem to benefit from citation spillover effects among the different topics in business and from a wider circulation than papers published in economics journals. Lastly, if faculty cannot also publish in Q2–Q3 WoS journals, they must at least make sure that the venue they target is ranked Q1 or Q2 in Scopus, as this can increase their number of annual citations from 2.3 (if their paper is in a journal that is not Q1/Q2 in Scimago) to 5.1 (if it was Q1 or Q2 in Scimago).

Likewise, school and university administrators can make use of our results and recommendations to develop incentive schemes and revise their promotion and merit criteria in a way that would incentivize their faculty to pursue Q1 papers in WoS and to seek international and local collaboration with top-notch authors in their fields. This will optimize the number of citations over time and improve the school and institutional ranking. One way to do that, for instance, is by providing monetary awards and course release inducements for their faculty who are able to co-author Q1 WoS publications with well-established business scholars who have achieved an h-index above 20. Additionally, school administrators can set up joint platforms or research clusters within their business schools to encourage joint publications internally, especially among their economics and other business faculty. This further motivates the economics faculty to target business and management journals whenever possible, benefiting from the wider circulation and citations that business journals seem to generate compared to economics within the business subject/field. Lastly, business schools and school administrators need to pair WOS quartiles with Scimago quartiles in their research guidelines in order to ensure that faculty are aware of the need to publish in journals ranked concurrently across both systems. This will ensure that the majority of faculty, which usually cannot go after Q1, Q2, or Q3 in WoS, understand the importance of having their papers ranked in at least the first two tiers (Q1 and Q2) of Scimago to ensure a minimum number or threshold of citations.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Lastly, while the present paper contributes to our understanding of citation prediction in the business field, it is not without limitations. Most importantly, the results from the present paper are based on papers published by one school and from a relatively small sample size, and as such, the results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to all business schools. More papers are needed in that regard to collect more data with larger samples from other business schools with different research statuses and across different countries that would allow further extrapolation and corroboration of the findings from the present study. Second, given that the present paper was conducted across the entire business field, specific variables related to paper content apart from the number of pages could not be used to better gauge the quality of a paper and further understand the effect this might have on citations. Future papers might try to come up with a way to assess paper content and thoroughness across business domains, for instance, through identifying and using a set of methodology-related criteria, which would allow a better understanding of the article-related factors in influencing business citations in this case. Third, the present study only considered theoretical and empirical journal articles. Further studies might include all types of intellectual contributions and publications to further examine how the different types of publications might also influence or moderate the relationships in terms of citation count predictions found in the present study. Finally, with many authors in recent years warning about excessive use by scholars in general and in the business field specifically [31,32] of self-citations and cross-citations by their institutional colleagues as a means to improve citations, the use of citation counts, in general, is becoming a dubious way to gauge the true value or impact of a publication. Thus, further studies might consider instead excluding self and institution citations when examining the drivers of business citations, which would subsequently help better understand the determinants of scholarly impact for faculty and business schools alike.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to all sections of this paper, namely conceptualization, methodology, empirical analysis and results, and conclusion/discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors upon request. It can be further replicated using the information provided in Appendix A Table A1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Indicative list of the 236 articles based on their citation counts/rank.

Table A1.

Indicative list of the 236 articles based on their citation counts/rank.

| Rank | Publications | Number of Citations Per Year |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | El-Kassar, A.N. and Singh S.K. [33] | 146.33 |

| 2 | Itani, O.S. and Hollebeek, S.D. [34] | 70 |

| 3 | Singh, S.K. and El-Kassar, A.N. [35] | 66.33 |

| 4 | Yunis, M., Tarhini, A., and El-Kassar, A.N. [36] | 63.75 |

| 5 | Singh, S.K., Chen, J., Del Giudice, M., and El-Kassar, A.N. [37] | 57 |

| 6 | Itani, O.S., El-Kassar, A.N., and Loureiro, S.M.C. [38] | 56.67 |

| 7 | Jizi, M. [39] | 54.2 |

| 8 | Dabbous, A. and Tarhini, A. [40] | 54 |

| 9 | Farah, M.F., Hasni, M.J.S., and Abbas, A.K. [41] | 47.25 |

| 10 | Assaker, G. [42] | 44.5 |

| 11 | Ismail, H.N., Iqbal, A., and Nasr, L. [43] | 42 |

| 12 | Itani, O.S., Agnihotri, R., and Dingus, R. [44] | 40.4 |

| 13 | Farah, M.F., Ramadan, Z.B., and Harb, D.H. [45] | 31.33 |

| 14 | Herrera, A.M., Karaki, M.B., Rangaraju, S.K. [46] | 30.67 |

| 15 | Hallak, R., Assaker, G., O’Connor, P., and Lee, C. [47] | 30 |

| 16 | Agnihotri, R., Trainor, K.J., Itani, O.S., Rodriguez, M. [48] | 28 |

| 17 | Itani, O.S., El-Haddad, R., and Kalra, A. [49] | 27 |

| 18 | Assaker, G. and O’Connor, P. [50] | 26 |

| 19 | Abosag, I., Ramadan, Z.B., Baker, T., and Jin, Z. [51] | 25.5 |

| 20 | Yunis, M., El-Kassar, A.N., and Tarhini, A. [52] | 24.8 |

| 21 | Agnihotri, R., Gabler, CB., Itani, O.S., Jaramillo, F., and Krush, M.T. [53] | 24.4 |

| 22 | O’Connor, P. and Assaker, G. [54] | 24 |

| 23 | ElGammal, W., El-Kassar, A.N., and Messarra, L.C. [55] | 23.5 |

| 24 | Mrad, M. and Cui, C.C. [56] | 23 |

| 25 | Hallak, R., Assaker, G., and El-Haddad, R. [57] | 22.75 |

| 26 | Arayssi, M., Jizi, M., and Tabaja, H.H. [58] | 22.67 |

| 27 | Harakeh, M., ElGammal, W., and Matar, G. [59] | 20.67 |

| 28 | Assaker, G., O’Connor, P., and El-Haddad, R. [60] | 20.5 |

| 29 | Itani, O.S., Krush, M.T., Agnihotri, R., and Trainor, K.J. [61] | 20 |

| 30 | Dabbous, A. and Tarhini, A. [62] | 19.67 |

| 31 | Ramadan, Z., Farah, M.F., and El Essrawi, L. [63] | 18 |

| 32 | Mrad, M., Majdalani, J., Cui, C.C., and El Khansa, Z. [64] | 18 |

| 33 | Itani, O.S., Goad, E.A., and Jaramillo, F. [65] | 16.33 |

| 34 | Itani, O.S., Jaramillo, F., and Paesbrugghe, B. [66] | 16 |

| 35 | Kim, S., Morgan, A., and Assaker, G. [67] | 15 |

| 36 | Farah, M.F. [68] | 14.6 |

| 37 | Dah, M.A. and Frye, M.B. [69] | 14.6 |

| 38 | Jizi, M. and Nehme, R. [70] | 14.5 |

| 39 | Ismail, H.N., and Rishani, M. [71] | 13.5 |

| 40 | Ramadan, Z.B., Farah, M.F., and Mrad, M. [72] | 13.4 |

| 41 | Assaker, G., Hallak, R., and El-Haddad, R. [73] | 13 |

| 42 | Alnakhli, H., Singh, R., Agnihotri, R., Itani, O.S. [74] | 13 |

| 43 | Itani, O.S., Jaramillo, F., and Chonko, L. [75] | 13 |

| 44 | Lythreatis, S., Singh, A.K., and El-Kassar, A.N. [76] | 13 |

| 45 | Awada, M., Srour, F.J., and Srour, I.M. [77] | 13 |

| 46 | Cui, C.C., Mrad, M., and Hogg, M.K. [78] | 12.75 |

| 47 | Ferreira, A.I., Mach, M., Martinez, L.F., Brewster, C., Dagher, G. [79] | 12.67 |

| 48 | Fakih, A., Haimoun, N., and Kassem, M., [80] | 12.5 |

| 49 | Farah, M.F. and Ramadan, Z.B. [81] | 12 |

| 50 | Eslami, H., Najem, S., Abi Ghanem, D., and Ahmad, A. [82] | 12 |

| 51 | Balozian, P. and Leidner, D. [83] | 12 |

| 52 | Farah, M.F. and Ramadan, Z.B. [84] | 11.8 |

| 53 | El-Kassar, A.N., Yunis, M., and El-Khalil, R. [85] | 10.8 |

| 54 | Sreih, J.F., Lussier, R.N., and Sonfield, M.C. [86] | 10.67 |

| 55 | Balozian, P., Leidner, D., and Warkentin, M. [87] | 10.67 |

| 56 | Ismail, H.N. and Gali. N. [88] | 10.6 |

| 57 | Assaker, G. [89] | 10.5 |

| 58 | Assaker, G., Hallak, R., and O’Connor, P. [90] | 10.5 |

| 59 | Freling, T.H., Yang, Z., Saini, R., Itani, O.S., and Abualsamh, R.R. [91] | 10.5 |

| 60 | ElGammal, W., Yassine, N., Fakih, K., and El-Kassar, A.N. [92] | 10.5 |

| 61 | Ramadan, Z.B., Farah, M.F., and Kassab, D. [93] | 10.33 |

| 62 | El-Kassar, A.N., Makki, D., and Gonzalez-Perez, M.A. [94] | 10 |

| 63 | Al-Dah, B., Dah, M., and Jizi, M. [95] | 10 |

| 64 | Nieroda, M.E., Mrad, M., and Solomon M.R. [96] | 9.5 |

| 65 | Arayssi, M. and Jizi, M. [97] | 9.25 |

| 66 | Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., and Marrouch, W. [98] | 9.25 |

| 67 | Abosedra, S., Arayssi, M., Sita, B.B., and Mutshinda, C. [99] | 9 |

| 68 | Farah, M.F. [100] | 8.8 |

| 69 | Karaki, M.B. [101] | 8.75 |

| 70 | Harakeh, M., Lee, E., and Walker, M. [102] | 8.67 |

| 71 | Singh, G.G., Hilmi, N., Bernhardt, J.R., Cisneros Montemayor, A.M. [103] | 8.67 |

| 72 | Mansour-Ichrakieh, L. and Zeaiter, H. [104] | 8.33 |

| 73 | Farah, M.F. and Shahzad, M.F. [105] | 8 |

| 74 | Mrad, M. and Cui, C.C. [106] | 8 |

| 75 | AlZaghrini, N., Srour, F.J., and Srour, I. [107] | 8 |

| 76 | Brown, G., Essex, S., Assaker, G., and Smith, A. [108] | 7.8 |

| 77 | Ramadan, Z.B. [109] | 7.67 |

| 78 | Ramadan, Z.B. [110] | 7.67 |

| 79 | Alsalman, Z.N. and Karaki, M.B. [111] | 7.67 |

| 80 | Herrera, A.M., Karaki, M.B., and Rangaraju, S.K. [112] | 7.6 |

| 81 | Brown, G., Assaker, G., and Reis, A. [113] | 7.5 |

| 82 | Ramadan, Z., Farah, M.F., and Dukenjian, A. [114] | 7.5 |

| 83 | Farah, M.F. [115] | 7.5 |

| 84 | Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., and Marrouch, W. [116] | 7.5 |

| 85 | Coutts, A., Daoud, A., Fakih, A., Marrouch, W., and Reinsberg, B. [117] | 7.33 |

| 86 | Jizi, M. and Nehme, R. [118] | 7.2 |

| 87 | El-Haddad, R., Karkoulian, S., and Nehme, R. [119] | 7 |

| 88 | Ramadan, Z.B. [120] | 7 |

| 89 | Ramadan, Z.B., Abosag, I., and Zabkar, V. [121] | 7 |

| 90 | Antounian, C., Dah, M.A., and Harakeh, M. [122] | 7 |

| 91 | Harakeh, M. [123] | 7 |

| 92 | El-Kassar, A.N., Messarra, L.C., and El-Khalil, R. [124] | 6.8 |

| 93 | Srour, F.J., Srour, I., and Lattouf, M.G. [125] | 6.8 |

| 94 | Srour, F.J., Agatz, N., and Oppen, J. [126] | 6.75 |

| 95 | Mrad, M., Farah, M.F., and Haddad, S. [127] | 6.67 |

| 96 | Chedrawi, C., Howayeck, P., and Tarhini, A. [128] | 6.67 |

| 97 | Lam, V.W.Y, Chavanich, S., Djoundourian, S., Dupont, S. [129] | 6.67 |

| 98 | Mrad, M. [130] | 6.5 |

| 99 | El-Kassar, A.N., ElGammal, W., and Fahed-Sreih, J. [131] | 6.25 |

| 100 | El-Khalil, R. and El-Kassar, A.N. [132] | 6.25 |

| 101 | Itani, O.S. and Hollebeek, L.D. [133] | 6 |

| 102 | Itani, O.S. and Chaker, N.N. [134] | 6 |

| 103 | Ramadan, Z.B., Farah, M.F., and Bou Saada, R. [135] | 6 |

| 104 | Farah, M.F. and Mehdi, N.I. [136] | 6 |

| 105 | Liu, Y., Abi Aad, A., Maalouf, J.T., and Abou Hamdan, O. [137] | 6 |

| 106 | Aoun Barakat, K., Dabbous, A., and Tarhini, A. [138] | 6 |

| 107 | Al-Shaer, H. and Harakeh, M. [139] | 6 |

| 108 | Dah, M.A., Jizi, M., and Kebbe, R. [140] | 6 |

| 109 | Barakat, A. and Fakih, A. [141] | 6 |

| 110 | Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., and Marrouch, W. [142] | 6 |

| 111 | Dah, M.A. and Jizi, M. [143] | 5.75 |

| 112 | Ramadan, Z.B. [144] | 5.67 |

| 113 | Ismail, H.N., Karkoulian, S., and Kertechian, S. [145] | 5.67 |

| 114 | Arayssi, M., Fakih, A., and Haimoun, N. [146] | 5.67 |

| 115 | Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., and Marrouch, W. [147] | 5.67 |

| 116 | Cao, X., Ouyang, T., Balozian, P., and Zhang, S. [148] | 5.5 |

| 117 | Kiomjian, D., Srour, I., and Srour, F.J. [149] | 5.5 |

| 118 | Abdallah, A. A.-N. and Abdallah, W. [150] | 5.33 |

| 119 | Mach, M., Ferreira, A.I., Martinez, L.F., Lisowskaia, A. [151] | 5.25 |

| 120 | Azadeh, A., Ahmadzadeh, K., and Eslami, H. [152] | 5 |

| 121 | Bandaly, D.C. and Hassan, H.F. [153] | 5 |

| 122 | El-Kassar, A.N., Yunis, M., Alsagheer, A., Tarhini, A., and Ishizaka, A. [154] | 5 |

| 123 | Harakeh, M., Lee, E., and Walker, M. [155] | 5 |

| 124 | Hilmi, N., Djoundourian, S., Shahin, W., and Safa, A. [156] | 5 |

| 125 | Ramadan, Z.B. [157] | 4.8 |

| 126 | Tarhini, A., Yunis, M., and El-Kassar, A.N. [158] | 4.75 |

| 127 | Tarhini, A., Tarhini, J., and Tarhini, A. [159] | 4.67 |

| 128 | Nehme, R. [160] | 4.6 |

| 129 | Ghazalian, P.L. and Fakih, A. [161] | 4.6 |

| 130 | Maalouf, J.T., Combs, J., Gillis, W.E., and Perryman, A. [162] | 4.5 |

| 131 | Harakeh, M., Matar, G., and Sayour, N. [163] | 4.5 |

| 132 | Jizi, M. and Dixon, R. [164] | 4.4 |

| 133 | Arayssi, M. and Fakih, A. [165] | 4.4 |

| 134 | Karkoulian, S., Srour, F.J., and Messarra, L.C. [166] | 4.33 |

| 135 | Abi Aad, A. and Combs, J.G. [167] | 4 |

| 136 | Fares, J., Chung, K.S.K., Passey, M., Longman, J., and Valentijn, P.P. [168] | 4 |

| 137 | Ismail, H.N., El Irani, M., and Kertechian, K.S. [169] | 4 |

| 138 | Tarhini, A., Balozain, P., and Srour, F.J. [170] | 4 |

| 139 | Tarhini, A., Danach, K., and Harfouche, A. [171] | 4 |

| 140 | Arayssi, M., Fakih, A., and Kassem, M. [172] | 4 |

| 141 | Karaki, M.B. [173] | 4 |

| 142 | Marrouch, W. and Mourad, J. [174] | 4 |

| 143 | Djoundourian, S.S. [175] | 4 |

| 144 | Haj Youssef, M., Hussein, H., and Christodoulou, I. [176] | 3.67 |

| 145 | Fakih, A. and Marrouch, W. [177] | 3.67 |

| 146 | Schröder, M. [178] | 3.6 |

| 147 | Maalouf, J.T., Abi Aad, A., and El Masri, K. [179] | 3.5 |

| 148 | Jaafar, R., Pereira, V., Saab, S.S., and El-Kassar, A.N. [21] | 3.5 |

| 149 | Ladki, S. and Mazeh, R. [180] | 3.4 |

| 150 | Sayour, N. [181] | 3.33 |

| 151 | Karaki, M.B. [182] | 3.25 |

| 152 | Fahed-Sreih, J. and EL-Kassar, A.N. [183] | 3.2 |

| 153 | El-Haddad, R. [184] | 3 |

| 154 | Itani, O.S., Kalra, A., Chaker, N.N., and Singh, R. [185] | 3 |

| 155 | Farah, M.F., Ramadan, Z.B., and Kanso, J. [186] | 3 |

| 156 | Ramadan, Z.B., Farah, M.F., and Daouk, S. [187] | 3 |

| 157 | Fares, J., Chung, K.S.K., and Abbasi, A. [188] | 3 |

| 158 | Hussein, H.H. and Haj Youssef, M. [189] | 3 |

| 159 | Srour, F.J., Kiomjian, D., and Srour, I.M. [190] | 3 |

| 160 | Abdallah, A. A.-N., Abdallah, W., and Salama, F.M. [191] | 3 |

| 161 | Nehme, R. and Jizi, M. [192] | 3 |

| 162 | Abosedra, S., Laopodis, N.T., and Fakih, A. [193] | 3 |

| 163 | Bitar, N., Chakrabarti, A., and Zeaiter, H. [194] | 3 |

| 164 | Haj Youssef, M. and Teng, D. [195] | 2.75 |

| 165 | Nehme, R., AlKhoury, C., and Al Mutawa, A. [196] | 2.67 |

| 166 | Hilmi, N., Osborn, D., Acar, S., Bambridge, T. [197] | 2.67 |

| 167 | Gabler, C.B., Agnihotri, R., and Itani, O.S. [198] | 2.6 |

| 168 | Simendinger, E., El-Kassar, A.N., Gonzalez-Perez, M.A., and Crawford, J. [199] | 2.6 |

| 169 | Arayssi, M. and Fakih, A. [200] | 2.6 |

| 170 | Itani, O.S. [201] | 2.5 |

| 171 | Ramadan, Z.B. and Farah, M.F. [202] | 2.5 |

| 172 | Haj Youssef, M., Hussein, H.M., and Awada, H. [203] | 2.5 |

| 173 | El-Kassar, A.N., Ishizaka, A., Temouri, Y., Al Sagheer, A., and Vaz, D. [204] | 2.5 |

| 174 | Ramadan, Z.B. and Farah, M.F. [205] | 2.4 |

| 175 | Haj Youssef, M., and Christodoulou, I. [206] | 2.4 |

| 176 | Alnakhli, H., Inyang, A.E., and Itani O.S. [207] | 2 |

| 177 | Ramadan, Z.B. and Nsouli, N.Z. [208] | 2 |

| 178 | Farah, M.F., Ramadan, Z.B., and Shatila, L. [209] | 2 |

| 179 | Naveed, M., Farah, M.F., and Hasni, M.J.S. [210] | 2 |

| 180 | Haj Youssef, M. and Teng, D. [211] | 2 |

| 181 | Srour, F.J. and Karkoulian, S. [212] | 2 |

| 182 | Balozian, P., Leidner, D., and Xue, B. [213] | 2 |

| 183 | Abdallah, A. A.-N., Abdallah, W., and Saad, M. [214] | 2 |

| 184 | Dah, M., Jizi, M., and Sbeity, S. [215] | 2 |

| 185 | Abosedra, S., Fakih, A., Ghosh, S., and Kanjilal, K. [216] | 2 |

| 186 | Karaki, M.B. [217] | 2 |

| 187 | Fakih, A., Ghazalian, P., and Ghazzawi, N. [218] | 2 |

| 188 | Smith, A., Brown, G., and Assaker, G. [219] | 1.8 |

| 189 | Fahed-Sreih, J. and El-Kassar, A.N. [220] | 1.75 |

| 190 | Fakih, A. [221] | 1.75 |

| 191 | Fox, R. and Schröder, M. [222] | 1.75 |

| 192 | Haj Youssef, M. and Christodoulou, I. [223] | 1.6 |

| 193 | Haj Youssef, M. and Christodoulou, I [224] | 1.6 |

| 194 | Elsiefy, E. and ElGammal, W. [225] | 1.6 |

| 195 | Abosedra, S. and Fakih, A. [226] | 1.6 |

| 196 | El-Kassar, A.N., ElGammal, W., Trabelsi, S., and Kchouri, B. [227] | 1.5 |

| 197 | Gilsinan, J.F., Fisher, J.E., Islam, M., Ordower, H.M., and Shahin, W. [228] | 1.5 |

| 198 | Abdallah, A. A.-N. and Abdallah, W. [229] | 1.4 |

| 199 | Haj Youssef, M. and Christodoulou, I [230] | 1.25 |

| 200 | Bandaly, D.C., Shanker, L., and Şatır, A. [231] | 1.25 |

| 201 | Azadeh, A., Kalantari, M., Ahmadi, G., Eslami, H. [232] | 1 |

| 202 | Fares, J. and Chung, K.S.K. [233] | 1 |

| 203 | Moukaddem, A.B., Azzam, N.J., and El-Kassar, A.N. [234] | 1 |

| 204 | Ginzarly, M. and Srour, J.F. [235] | 1 |

| 205 | Nehme, R., Michael, A., and Kozah, A.E. [236] | 1 |

| 206 | Nehme, R., Michael, A., and Haslam, J. [237] | 1 |

| 207 | Fakih, A. and Ghazalian, P.L. [238] | 1 |

| 208 | Marrouch, W. and Sayour, N. [239] | 1 |

| 209 | Zeaiter, H. and Kassem, M. [240] | 1 |

| 210 | Djoundourian, S.S. [241] | 1 |

| 211 | He, A. and Sayour, N. [242] | 1 |

| 212 | Engle-Warnick, J., Laszlo, S., and Sayour, N. [243] | 1 |

| 213 | Bazi, G., El Khoury, J., and Srour, F.J. [244] | 0.8 |

| 214 | Aintablian, S., El-Khoury, W., and M’Chirgui, Z. [245] | 0.8 |

| 215 | Toukan, A. [246] | 0.8 |

| 216 | Ladki, S. and Bachir, N. [247] | 0.75 |

| 217 | Haj Youssef, M. and Christodoulou, I. [248]) | 0.6 |

| 218 | Ladki, S., Abimanyu, A., and Kesserwan, L. [249] | 0.5 |

| 219 | ElGammal, W. and Gharzeddine, M. [250] | 0.5 |

| 220 | Ramadan, Z.B. and Mrad, M. [251] | 0.4 |

| 221 | Aintablian, S. and El-Khoury, W. [252] | 0.4 |

| 222 | Kertechian, S.K., Karkoulian, S., Ismail, H.N., and Nassif, P. [253] | 0.33 |

| 223 | Dah, B.A., Dah, M.A., and Zantout, M.H. [254] | 0.2 |

| 224 | Hasni, M.J.S., Farah, M.F., and Adeel, I. [255] | 0 |

| 225 | Fahed-Sreih, J. and Khalife, J. [256] | 0 |

| 226 | Abi Aad, A., Andrews, M.C., Maalouf, J.T., Kacmar, K.C., and Valle, M. [257] | 0 |

| 227 | Armache, J., Ismail, H.N., and Armache, G.D. [258] | 0 |

| 228 | Haj Youssef, M. and Teng, D. [259] | 0 |

| 229 | Kertechian, S.K., Karkoulian, S., Ismail, H.N., and Aad Makhoul, S.S. [260] | 0 |

| 230 | Xue, B., Warkentin, M., Mutchler, L.M., and Balozian, P. [261] | 0 |

| 231 | Fakih, K. [262] | 0 |

| 232 | Abdallah, A. A.-N., Abdallah, W., and Saad, M. [263] | 0 |

| 233 | Jizi, M., Nehme, R., and Melhem, C. [264] | 0 |

| 234 | Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., Marrouch, W., and Matar, G. [265] | 0 |

| 235 | Islam, M., Gilsinan, J., Shahin, W., and Fisher, J. [266] | 0 |

| 236 | Schröder, M. [267] | 0 |

References

- Paphawasit, B.; Wudhikarn, R. Investigating Patterns of Research Collaboration and Citations in Science and Technology: A Case of Chiang Mai University. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Raman, R.; Stubblefield, A. What Affects Citation Counts in MIS Research Articles? An Empirical Investigation. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2014, 34, 1435–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahamtan, I.; Safipour Afshar, A.; Ahamdzadeh, K. Factors affecting number of citations: A comprehensive review of the literature. Scientometrics 2016, 107, 1195–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Cable, D.M.; Colbert, A.E.; Rynes, S.L. What Causes a Management Article to Be Cited: Article, Author, or Journal? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, D. Pressure for Relevancy at Top-Tier Business Schools. J. Manag. Inq. 2005, 14, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.; Arbaugh, J.B.; Bento, R.F.; Asarta, C.J.; Fornaciari, C.J. What causes a Business and Management Education article to be cited: Article, author, or journal? Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACSB Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Guiding Principles and Standards 2020. Tampa, FL: AACSB. Available online: https://www.aacsb.edu/educators/accreditation/business-accreditation/aacsb-business-accreditation-standards (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Bai, X.; Zhang, F.; Lee, I. Predicting the citations of scholarly paper. J. Informetr. 2019, 13, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; Xu, F. The drivers of citations in management science journals. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 205, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheili, F.; Khasseh, A.A.; Mokhtari, H.; Sadeghi, M. Factors Affecting the Number of Citations: A Mixed Method Study. J. Scientometr. Res. 2022, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremersch, S.; Camacho, N.; Vanneste, S.; Verniers, I. Unraveling scientific impact: Citation types in marketing journals. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaminfirooz, M.; Ardali, F.R. Identifying the Factors Affecting Papers’ Citability in the Field of Medicine: An Evidence-based Approach Using 200 Highly and Lowly-cited Papers. Acta Inform. Med. 2018, 26, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Shapiro, D.L.; Antonacopoulou, E.P.; Cummings, T.G. Scholarly impact: A pluralist conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Chen, C.R.; Fung, H.-G. Pedigree or Placement? An Analysis of Research Productivity in Finance. Financ. Rev. 2009, 44, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.P.; Burns, R. Business Research Methods and Statistics Using SPSS; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, J.; Turrisi, R. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Pérez, F.M.; Bethencourt-Cejas, M. CHAID algorithm as an appropriate analytical method for tourism market segmentation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, M.; Stamenković, M. CHAID Decision Tree: Methodological Frame and Application. Economic Themes 2016, 54, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Hastak, M. Segmentation approaches in data-mining: A comparison of RFM, CHAID, and logistic regression. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Houston, M.B. The Impact of Article Method Type and Subject Area on Article Citations and Reference Diversity in JM, JMR, and JCR. Mark. Lett. 2001, 12, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, R.; Pereira, V.; Saab, S.S.; El-Kassar, A.-N. Which journal ranking list? A case study in business and economics. EuroMed J. Bus. 2020, 16, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRyalat, S.A.; Saleh, M.; Alaqraa, M.; Alfukaha, A.; Alkayed, Y.; Abaza, M.; Abu Saa, H.; Alshamiry, M. The impact of the open-access status on journal indices: A review of medical journals. F1000Research 2019, 8, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koler-Povh, T.; Južnič, P.; Turk, G. Impact of open access on citation of scholarly publications in the field of civil engineering. Scientometrics 2014, 98, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langham-Putrow, A.; Bakker, C.; Riegelman, A. Is the open access citation advantage real? A systematic review of the citation of open access and subscription-based articles. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Leydesdorff, L.; Wang, J. How to improve the prediction based on citation impact percentiles for years shortly after the publication date? J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögårde, P.; Didegah, F. The association between topic growth and citation impact of research publications. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 1903–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcsák, Z. Researcher Performance in Scopus Articles (RPSA) as a New Scientometric Model of Scientific Output: Tested in Business Area of V4 Countries. Publications 2021, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padial, A.A.; Nabout, J.C.; Siqueira, T.; Bini, L.M.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. Weak evidence for determinants of citation frequency in ecological articles. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, F.M.; Gamel, S.A. Predicting the impact of no. Of authors on no. Of citations of research publications based on neural networks. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPSS User’s Manual (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Documentation. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/ibm-spss-statistics-26-documentation (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Fraser, K.; Deng, X.; Bruno, F.; Rashid, T.A. Should academic research be relevant and useful to practitioners? The contrasting difference between three applied disciplines. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.; Sheehy, B. Abundant Publications but Minuscule Impact: The Irrelevance of Academic Accounting Research on Practice and the Profession. Publications 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.-N.; Singh, S.K. Green innovation and organizational performance: The influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]