Abstract

Background: Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has been proposed as an effective alternative method for the adjunctive treatment of all classes of oral infections. The multifactorial nature of its mechanism of action correlates with various influencing factors, involving parameters concerning both the photosensitizer and the light delivery system. This study aims to critically evaluate the recorded parameters of aPDT applications that use lasers as the light source in randomized clinical trials in dentistry. Methods: PubMed and Cochrane search engines were used to identify human clinical trials of aPDT therapy in dentistry. After applying specific keywords, additional filters, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the initial number of 7744 articles was reduced to 38. Results: Almost one-half of the articles presented incomplete parameters, whilst the others had different protocols, even with the same photosensitizer and for the same field of application. Conclusions: No safe recommendation for aPDT protocols can be extrapolated for clinical use. Further research investigations should be performed with clear protocols, so that standardization for their potential dental applications can be achieved.

1. Introduction

The discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928 was one of the scientific highlights of the last century. In the 1940s, antibiotics had been introduced to the market and in the 1980s, pharmaceutical companies were declaring the “end” of infectious diseases. Unfortunately, microorganisms remained, and the extensive and inappropriate use of antibiotics gradually led to the development of pervasive antimicrobial resistance. Since the efficacies of antibiotics decreases and the end of the “antibiotic era” gets closer, efforts to discover new ways to eradicate microorganisms and eliminate multidrug resistance phenomena are evolving. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) therefore serves as a promising approach [1].

Photodynamic therapy is a non-thermal photochemical reaction that involves the excitation of a non-toxic dye (photosensitizer-PS) by light at an appropriate wavelength, to produce a long-lived triplet state that can interact with molecular oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen (1O2), which can damage biomolecules, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids [2]. Each of the above-mentioned components (photosensitizer, light and oxygen) are harmless by themselves, but in combination lead to lethal cytotoxic ROS that can selectively destroy cells [3]. This therapy affects the target tissue, which is exposed both to a light source and photosensitizer simultaneously. It shows a dual selectivity, which is based on the different concentrations of the photosensitizer used between normal and target tissue, and also on the spatial confinement of the light only in the target [4].

Photosensitizers are usually organic aromatic molecules with delocalised π electrons, where a central chromophore is covalently bonded to auxiliary substituent branches, which contribute to further electron delocalisation. In this manner, the absorption spectrum of the photosensitizer moiety is modified [5]. They should absorb light at the red or near-infrared wavelengths (600–800 nm). Shorter wavelengths (i.e., those <600 nm) have less penetration and longer wavelengths (i.e., >800 nm) do not have sufficient inherent photonic energy to interact with and induce photodynamic reactions [6].

The source of light must coincide with the absorption maximum of each photosensitizer used. Devices that can be employed include broad-spectrum lamps, light-emitting diodes (LED) or lasers. Amongst these, lasers have specific properties, which render them superior to the other sources. Monochromaticity is a unique and inherent characteristic that provides the laser with the possibility to interact with the photosensitizer by accurately matching its peak absorption. This results in less excess energy and tissue heating, which is sub-optimal in delivering the PDT reaction, when compared to the effects of broad bandwidth devices [7].

The main advantages of PDT are the wide spectrum of antimicrobial action; treatment outcomes are independent of the antibiotic resistance pattern, minimal damage to host tissue, the absence of photo-resistant strains of microorganisms after multiple treatments, a lack of mutagenicity, and minimally invasive and low-cost therapies [8].

Photodynamic therapy has been widely applied for cancer therapy in general medicine. Notwithstanding this, today the interest for antimicrobial PDT has increased in view of the consequences experienced with antibiotic overuse [8]. Several acronyms exist to describe this therapy and in order to avoid any confusion with photodynamic therapy applied for tumour treatments, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) is the most suitable term for antimicrobial purposes [9], as applied in dentistry.

The use of aPDT in dentistry can be readily justified, since the oral cavity is heavily populated with microorganisms, organised within biofilm structures that may show extremely high resistance to conventional antimicrobial agents [1]. Additionally, the uncontrolled systemic use of antibiotics has led to highly resistant microorganisms [10]. Thus, the investigation of an alternative potential treatment for local infections, such as photodynamic therapy, is mandated [11].

The mechanism of action of aPDT can be explained in the following manner: the ground electronic state of the photosensitizer is a singlet state, since it has two electrons paired with opposite spins within its external molecular orbital (highest occupied molecular orbital—HOMO). When the photosensitizer absorbs the appropriate quantum energy from a light source, one of these two electrons is excited to a higher-energy orbital (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital—LUMO). This is termed the first excited singlet-state [12]. To absorb a photon, the energy of the incident photon should be equal or higher than the HOMO–LUMO energy gap and the excess of energy is released through vibrational relaxation; on return to its ground state, the photosensitizer emits the absorbed energy as fluorescence, or produces heat by internal conversion, which is a non-radiative and rapid (less than a nanosecond) process in which electron spins remain the same [8]. Alternatively, the excited singlet-state photosensitizer can undergo a process known as “intersystem crossing” to form a more stable, first excited triplet state. Again, this process is non-radiative and involves a change in spin for the excited electron, so the photosensitizer now has two unpaired but parallel electrons [13]. This endures for <10 ns [8], and the excited triplet state has a lifetime of microseconds [2], so there is sufficient time to induce photochemical reactions. The triplet state also has a lower energy than the excited singlet state [1].

If there is no molecular oxygen (O2) available, the triplet state photosensitizer can eventually return to the ground state through internal or external fluorescence or phosphorescence [13]. However, in the presence of O2, the triplet excited state photosensitizer can participate in chemical reactions and provide photodynamic therapy. Indeed, there are two types of these reactions—Type I and Type II [2]. In Type I, hydrogen and electron transfers take place between the triplet excited state of the photosensitizer and other molecules, predominantly O2. With these chemical reactions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, that are very active and harmful towards many target cells [13]. These ROS predominantly consist of superoxide anion (O2●−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (●OH), and singlet oxygen (1O2) [2]. However, the converse, Type II reaction is much simpler, and involves energy transfer between the triplet state photosensitizer and O2. This results in the formation of ground state photosensitizer and 1O2 [2].

Singlet oxygen and ●OH radical can readily pass through cell membranes and are the most highly reactive ROS species. In view of this, only molecules that are closely located to their site of generation can be affected by photodynamic therapy [6]. Additionally, the lifetime of singlet oxygen (1O2) is very limited, depending on the surrounding solvent present [14], thus its action radius is approximately 10–55 nm [12]. Hence, the most important factor that influences the outcome of photodynamic therapy is the subcellular localisation of the photosensitizer which drives the process.

In general, the efficiency of the treatment can be affected by the following factors [6]:

- As noted above, the sub-cellular localisation of the photosensitizer. Within the target cell, the photosensitizer may affect lysosomes, mitochondria, the plasma membrane, Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum. Most of the photosensitizers localise within mitochondria, where apoptosis is provoked via mitochondrial damage; lysosomes accumulate photosensitizers with more aggregation. The photosensitizer Foscan (a chlorin named m-tetrahydroxyphenylchlorin) may target the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum [6]. However, the plasma membrane is rarely noted as a site of photosensitizer accumulation [10].

- The chemical characteristics of the photosensitizer. The different physiology of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria can affect the degree of binding of different photosensitizers. Indeed, Gram-positive bacteria can efficiently bind to cationic, neutral and anionic photosensitizers, while only cationic ones can bind to Gram-negative bacteria [15].

- The concentration of the photosensitizer applied. High concentrations of photosensitizer can be naturally cytotoxic in a non-illuminated state, and obstruct light transmission into tissue target sites [16].

- The blood serum content. The presence of serum in the medium can decrease the effectiveness of the therapy, in view of probable chemical and physicochemical interactions between such agents and selected serum biomolecules [17].

- The incubation time, also known as equilibration time, of the photosensitizer at target sites. This should ideally commence shortly prior to illumination (of a ca. a few minutes’ duration), since this favours localisation into the microorganisms, and does not allow penetration into host cells (this process requires many hours to occur) [18].

- The phenotype of the target cell. It is known that different tissue types have differential light optical properties of light (i.e., absorption and scattering) [6].

An understanding of the mode of action of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, and a knowledge of the structure of the target host tissue is essential. This should facilitate determination of the correct choice of photosensitizer (type, concentration, incubation time, etc.), and the correct light source (kind, power, illumination time, energy, spot size, distance from the target, technique applied, etc.) in order to produce a standardized protocol.

In the scientific literature, a variety of reports exist regarding the use of aPDT in dentistry. This technique has been tested in the treatment of periodontitis, peri-implantitis, endodontic conditions, dental caries and candida disinfection, wound healing and oral lichen planus (OLP). For the latter, photodynamic therapy has been suggested as an alternative treatment based on the inflammatory pathogenesis of OLP and the immunomodulatory effect of aPDT [19].

However, until now there is no consensus regarding the protocol to be applied. The aim of this study is to critically evaluate, by a systematic review of randomized clinical trials, the recorded parameters of laser aPDT applications in clinical dentistry and oral health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

An electronic search was conducted relating to aPDT applications in all fields of dentistry from 10 March until 20 March. Databases used were PubMed and Cochrane, with the following MeSH terms, keywords and their combinations: (1) (PDT OR aPDT OR photodynamic) AND laser; and (2) photodynamic AND (periodontitis OR peri-implantitis OR endodontic OR caries OR candida OR oral lichen OR halitosis).

After applying the additional filters (published within the last 10 years, only randomized clinical trials in humans, and only English language reports), the preliminary number of 7744 articles was reduced to 390.

Titles and abstracts of the above articles were independently screened by two reviewers via application of the following criteria. In case of any disagreements arising, these were satisfactorily resolved by discussions.

Inclusion criteria:

- laser used as light source;

- negative control group;

- at least 10 samples/patients per group;

- only randomized controlled clinical trials;

- correct combinations of photosensitizer (PS) and the laser source employed;

- a minimum of a 6 month follow-up for periodontitis/peri-implantitis articles.

Exclusion criteria:

- duplicates or studies with the same ethical approval number;

- tumours, general medical applications, aPDT form not used as a therapy;

- LED or lamps used as light sources;

- no negative control group;

- low sample/patients sizes (less than 10 per group);

- no randomized controlled clinical trials or pilot studies;

- erroneous combinations of photosensitizer and laser employed;

- for periodontitis/peri-implantitis articles:

- ➢

- <6 month follow-up

- ➢

- aPDT used as a monotherapy (without scaling and root planning—SRP)

After screening and implementation of the eligibility criteria, a total of 38 articles were retained. These concerned a range of different aspects of application fields in dentistry. Specifically, the number of articles per field was found to be:

- periodontitis: 17

- peri-implantitis: 4

- endodontics: 5

- caries disinfection: 5

- candida disinfection: 2

- halitosis: 1

- oral lichen planus (OLP): 3

- healing of pericoronitis: 1

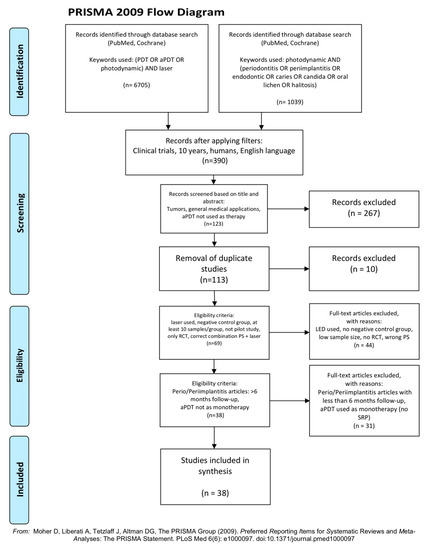

In accordance with the PRISMA statement [20], details of the selection criteria are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow-chart of selected criteria for the included article reports [20].

2.2. Data Extraction

Having reached a consensus regarding the selection of included articles, the two reviewers involved subsequently extracted data regarding:

- Citation (first author and publication year);

- Type of study/number of samples/pocket depth (only for periodontitis and peri-implantitis articles);

- Test/control groups;

- Laser and photosensitizer used (PS concentration);

- aPDT protocol/number of sessions involved;

- Follow-up;

- Outcome.

2.3. Quality Assessment

Subsequent to data extraction, articles were further evaluated by assessing their risk of bias assessment. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [21] was modified according to the requirements of this systematic review.

The risk of bias was determined according to the number of “yes” or “no” responses to the parameters provided below, which were allocated to each study:

- Randomization?

- Sample size calculation and required sample numbers included?

- Baseline situation similar to that of the test group?

- Blinding?

- Parameters of laser use described appropriately, and associated calculations correct?

- Power meter used?

- Numerical results available (statistics)?

- No missing outcome data?

- All samples/patients completed the follow-up evaluation?

- Correct interpretation of data acquired?

The classification was performed according to the total number of “yes” answers to the above questions. For the current study, the degree of bias was computed according to the score limits provided below:

- High risk: 0–4

- Moderate risk: 5–7

- Low risk: 8–10

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcome

The primary goal of this systematic review was to evaluate the studies explored with sufficient and reproducible parameter descriptions, and also analyse their aPDT protocols.

The parameters missing from the studies with incomplete protocols are also briefly noted.

3.2. Data Presentation

The extrapolated data evaluated for each dental research field are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Key: TBO—Toluidine Blue, MB—Methylene Blue, ICG—Indocyanine Green.

Table 1.

Studies of aPDT in periodontitis.

Table 2.

Studies of aPDT in periimplantitis.

Table 3.

Studies of aPDT in endodontics.

Table 4.

Studies aPDT in caries disinfection.

Table 5.

Studies with aPDT on Candida and halitosis.

Table 6.

Studies with aPDT in Oral Lichen Planus.

Table 7.

Study of aPDT in healing pericoronitis.

3.3. Quality Assessment Presentation

The risk of bias of the included studies is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Risk of bias assessment results.

In total, 21/38 of the articles (55.3%) showed a low risk of bias, with two articles [6,31] scoring 10/10, eleven [24,26,28,29,38,43,44,49,51,52,55] scoring 9/10, and eight [23,25,34,35,37,46,48,50] scoring 8/10.

Respectively, 17/38 of the articles (44.7%) showed a moderate risk of bias, with ten articles [22,27,32,33,39,42,47,53,58,59] scoring 7/10, and seven [30,40,41,45,54,56,57] scoring 6/10.

Overall, the mean ± standard error (SEM) Cochrane risk of bias score parameter was 7.76 ± 0.20 out of a perfect, optimal value of 10.

Apart from the correct description of the aPDT protocol, the most common negative answers concerned (a) use of a power meter, and (b) the sample size power calculation and required sampling numbers included.

3.4. Analysis of Data

Regarding the primary outcome, 22/38 articles (57.9%) presented an appropriate and sufficient description of the aPDT protocol used.

Specifically, for each dental research field, studies were allocated as:

- 8/17 in periodontitis [22,24,26,28,29,31,36,38];

- 2/4 in peri-implantitis [39,41];

- 4/5 in endodontics [43,44,46,47];

- 5/5 in caries disinfection [48,49,50,51,52];

- 0/2 in candida disinfection;

- 1/1 in halitosis [55];

- 2/3 in OLP [56,58];

- 0/1 in healing pericoronitis.

From these studies, 16/22 showed a low risk of bias, whilst 6/22 showed a moderate risk level.

The analysis of the aPDT protocols have been performed for each photosensitizer used, as listed in Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12:

Table 9.

Studies with methylene blue (MB). * Values predominantly applied.

Table 10.

Studies with toluidine blue (TBO).

Table 11.

Single study with indocyanine green (ICG).

Table 12.

Single study with polyethyleneimine and chlorin(e6) conjugate (PEI-ce6).

For investigations with incomplete parameter descriptions, 16/38 present the following deficiencies, as noted from Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7:

- incubation time: 2/16 (12.5%);

- power: 4/16 (25%);

- tip or spot size: 13/16 (81.2%);

- fluence value incorrectly calculated (i.e., either the tip or energy applied is erroneous): 2/16 (12.5%).

4. Discussion

Data analysis of the publications reviewed revealed a considerable variety in the report of parameters concerning the use of aPDT treatments in different dental fields. This is in accordance with Parker et al. [60], and points out the necessity to adopt clear information on the materials and methods. We then considered studies with an appropriate description of aPDT protocols, specifically those which indicated, or allowed us to calculate, the following parameters: power, irradiation time, total energy delivered, tip diameter or spot size at target tissue, any movement and speed of movement, the photosensitizer used, its applied concentration, its incubation time, and finally protocols available for washing it away or not prior to illumination. The ideal reporting of an aPDT protocol is indicated in Table 13.

Table 13.

Ideal reporting required for aPDT treatment regimen parameters.

An important aspect to be considered is the use of a power meter prior to the illumination process. Indeed, the laser should be calibrated in order for investigators to obtain precise parameters to record, so that a standardised protocol can be provided [61]. In this review, only 6/38 [29,31,36,51,52,55] articles used a power meter (Table 8).

With regard to the treatment outcomes observed in the surveyed investigations, only 2/38 studies showed negative results when expressed relative to those of their corresponding control groups. The remainder of the investigations showed either positive (22/38) or indifferent (14/38) result outcomes when compared to results acquired for their corresponding control groups. This heterogeneity can be mainly attributed to the different protocols applied (i.e., either laser or photosensitizer parameters, as described above). Moreover, other factors that should be considered are the complex pocket or root canal architecture, unknown total volume irradiation of the photosensitizer, and the variable numbers of treatment sessions employed by investigators.

4.1. aPDT Components

As noted in the introduction, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy is based on the combination of three components: the photosensitizer nature, light and O2 [2]. Basic information available on each of these considerations is further analysed below.

4.1.1. Photosensitizers

The vast majority of articles used methylene blue (MB) as the photosensitizer, which has an absorption band located at 660 nm. It is a cationic and hydrophilic compound, i.e., an amphipathic molecule (one that combines both polar and non-polar moieties), which has a low molecular mass [3]. In view of its charge, it can bind to the lipopolysaccharides of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and also to the teichuronic acid residues of the outer membrane of Gram-positive bacteria [7].

Another popular photosensitizer is toluidine blue (TBO), with an absorption band centred at 635 nm [7]. It is a blue colouring agent also with amphipathic characteristics, but with a positive charge and a hydrophilic portion [62]. In view of its charge, it can bind both to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [7], as documented above.

The other photosensitizer used in studies included in this review is indocyanine green (ICG). It is a green colouring agent, with anionic charge, and also has amphiphilic characteristics; indeed, its polycyclic components are lipophilic [9]. It has an absorption band with a maximum at 810 nm (although this precise value is critically dependent on the dissolution medium employed), its concentration and extent of binding to blood plasma proteins [7]. Notably, its mechanism of action is predominately based on photothermal (80%) rather than photochemical (20%) processes [63].

The final photosensitizer included is the chlorin(e6) conjugate of polyethyleneimine (PEI-ce6). It is a polycationic macromolecule, and its treatment efficacy is dependent on the molecular size (smaller values lead to greater diffusion into cells), and the cationic charge (the higher the charge, the more effective it is). As expected, its absorption spectrum in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum is the same as that of the free chlorin(e6) conjugating agent with absorption maxima located at 400 and 670 nm [64,65].

Unfortunately, studies with curcumin, 5-aminolevulinic acid, rose Bengal and erythrosine used as photosensitizers have not been included, since they failed to meet the inclusion criteria of this review. To date, there are no published human clinical trials using 5-aminolevulinic acid, rose Bengal and erythrosine as photosensitizers in the dental fields. Notwithstanding, for curcumin, there are recent human clinical trials that reported using LEDs as the light source, and with promising results obtained [66,67,68,69,70,71].

4.1.2. Light Diffusion

Light distribution depends on the shape of the beam [72]; thus, diffusor tips, as used in the included studies [22,33,40,41,42,46], are preferable since they lead to a three-dimensional illumination [73]. As Garcez et al. pointed out, the use of a conventional tip inside the root canal will lead to ROS generation in the middle of the canal, and not inside the dentin walls, where most of the microorganisms are located [74].

Furthermore, the optical properties of the target tissue play a crucial role regarding the diffusion of light. As noted in [72], these can be identified as (a) different refraction and scattering indexes when light passes through differing media, as previously noted for trans-gingival use [75]; (b) competitive light absorbers; and (c) unevenly distributed absorbers, since the photosensitizer can lead to local “cold spots” as far as the applied irradiance is concerned [72].

Regarding the use of trans-gingival as an aPDT, as applied in studies [36,38] evaluated here, such a therapy may be considered a novel approach, and this approach appears to be able to bypass the limitation of light in accessing complex target areas, such as root furcations or deep periodontal pockets [76,77]. It is known that the penetration depth of the 660 nm wavelength is 3–3.5 mm, while that for the range of 800–900 nm is 6–6.5 mm [76]. However, it is essential to consider that light attenuation occurs within gingival tissue. Specifically, for red light at a depth of 3 mm inside the gingival tissue, there is a 50% loss of intensity [75].

With regard to the competitive host absorbers of light, such as haemoglobin and a wide range of other proteins, it is mandatory to consider that their presence can decrease the effectiveness of the therapy applied [17,78]. Therefore, the outcome should be carefully evaluated when the aPDT technique is applied immediately after the SRP or pocket debridement, as was indeed the case in the majority of the studies included here for periodontitis and peri-implantitis treatment (13/21). Respectively, in endodontic therapy, the root canals should be dried prior to application of the photosensitizer. The photosensitizers used within a confined space, i.e., a root canal or a periodontal pocket, are investigated at a precise, pre-calculated concentration. If, for any reason, this space is not “dry”, the photosensitizer may not achieve the concentration required for its optimal activity.

Higher concentrations of photosensitizer applied can lead to limitations in its ability to absorb light, either by the “photobleaching” phenomenon [79], or alternatively the “optical shielding” effect [6]. The former occurs when ROS generated chemically react with the photosensitizer, as noted above, and hence circumvents any further photosensitization process [79]. The latter refers to the blocking of light in view of high superficial absorption, and prevention of the light from reaching deeper tissue layers [74].

The above mentioned three photosensitizers (MB, TBO and ICG) can be considered to be ROS-scavenging antioxidant molecules [79].

4.1.3. Oxygen

Sufficient oxygenation of the target tissue is crucial for inducing and propagating the direct oxidative damage of microorganisms [80]; in deep and less oxygenated areas, such as in root canals, there is an O2 deficiency. To surmount this hurdle, firstly ICG, with its photothermal action, can be used to enhance the elimination of microorganisms, although thermal damage to surrounding tissues should be taken into consideration [81]. Secondly, pre-treatment of root canals with H2O2 has been suggested. This will enhance O2 availability in this environment and allow an improved penetration of the photosensitizer inside microbial biofilms, a process leading to a higher level of antimicrobial effectiveness [74].

4.2. Healing

The healing of tissues is known to be improved following photodynamic therapy, rendering this treatment regimen a valuable choice for wounds or other infections. An additional consideration is that in many local infections, the photosensitizer is topically administered to the infected area, and the delivered light diffuses and scatters well beyond the actual area of interest. This light can exert a substantial secondary therapeutic beneficial effect in stimulating healing and repair within the surrounding tissues by a process known as photobiomodulation (PBM) [18]. Even if the whole of the photosensitizer dye solution cannot be activated, the benefits offered by PBM are invaluable [76].

4.3. Clinical Aspects

The most investigated and effective photosensitizer is methylene blue; indeed, it was applied in a total of 29 out of the 38 studies included in the present review applied MB as the photosensitizer. Nevertheless, ICG is a very promising agent, since it is activated by an 810 nm laser, which can penetrate deeper into tissues, and therefore, trans-tissue illumination is possible. In addition, in view of its additional photothermal actions (80%), applications inside root canals, where oxygen is limited, are preferential.

However, to date there is no ideal PS available, and hence clinicians should bear in mind the following characteristics before making their choice [13]:

- Selectivity for prokaryotic cells over eukaryotes, so that collateral damage to healthy tissue is minimised;

- Short incubation time, so that binding selectivity is achieved;

- High quantum yields for photochemical reactions and low quantum yields for photobleaching;

- High extinction coefficient, which demonstrates the ability of a molecule to absorb light at a specific wavelength (usually at the maximum absorption band) [8];

- Possess cationic charge and therefore be effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms;

- Ability to kill multiple kinds of microorganisms at low concentrations and at low light fluences;

- Low side effects, such as photosensitivity and pain;

- Low dark toxicity without applied illumination;

As far as the light dose is concerned, it should be noted that high fluence irradiation will lead to the depletion of molecular oxygen into the tissue, and this will give rise to an impairment of therapy efficacy [13].

From the included studies with appropriate and sufficient description of the aPDT protocol applied (Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12), the authors suggest that the power and incubation time of PS should not exceed 200 mW and 5 min, respectively (only two studies [56,58] used a 10 min duration with coupled TBO) and that the irradiation time should not be less than 30 s.

All the above have the prerequisite that the clinician has understood the mechanism of action of photodynamic therapy and its influencing factors outlined in the introduction section, and can therefore select the correct combinations of the photosensitizers and lasers for upcoming dental treatments.

5. Conclusions

Photodynamic therapy has been acknowledged to effectively eliminate microorganisms and enhance tissue healing processes. The scope of this systematic review was to critically appraise the recorded aPDT protocols in current clinical trials featuring this form of therapy. Almost half of the articles presented incomplete parameters, whilst the remainder had differential protocols, even with the same photosensitizer and for the same field of application. Consequently, no safe recommendation on aPDT protocols can be extrapolated for clinical use at this point in time.

Unfortunately, light dosimetry is still not widely embraced in clinical aPDT. The main reason for this may be that the effects and benefits of photomedicine are multifactorial, and that the high levels of mathematics, physics and optical technologies are not easily incorporated into clinical practices and their research investigations.

For future directions, more research studies should be performed with clear, validated protocols, so that standardisation in a range of dental applications may be achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M. and E.A.; methodology, V.M. and E.A.; validation, V.M., E.A. and S.P.; formal analysis, V.M.; investigation, V.M. and E.A.; resources, V.M.; data curation, V.M. and E.A.; writing-original draft preparation, V.M.; writing-review and editing, E.A., S.P., M.C., E.L. and M.G.; statistical analysis, M.G.; visualization, V.M.; supervision, E.L. and M.G.; project administration, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- St. Denis, T.G.; Dai, T.; Izikson, L.; Astrakas, C.; Anderson, R.R.; Hamblin, M.R.; Tegos, G.P. All you need is light, antimicrobial photoinactivation as an evolving and emerging discovery strategy against infectious disease. Virulence 2011, 2, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Diaz, M.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Use of fluorescent probes for ROS to tease apart Type I and Type II photochemical pathways in photodynamic therapy. Methods 2016, 109, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera, E.T.; Dias, H.B.; Corbi, S.C.T.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Bernardi, A.C.A.; Bagnato, V.S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Rastelli, A.N.S. The application of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) in dentistry: A critical review. Laser Phys. 2016, 26, 12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, E.; Hynninen, P. Research advances in the use of tetrapyrrolic photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2004, 73, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, M.; Byrne, M.; Gattrell, M. Phenothiazinium-based photobactericidal materials. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2006, 84, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castano, A.P.; Demidova, T.N.; Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: Part one—Photosensitizers, photochemistry and cellular localization. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2004, 1, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, D.; Aoki, A.; Chiniforush, N. Light source Chapter 14.6. In Lasers in Dentistry-Current Concepts, 1st ed.; Coluzzi, D., Parker, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 309. ISBN 978-3-319-51944-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sellera, F.; Nascimento, C.; Ribeiro, M. Photodynamic Therapy in Veterinary Medicine: From Basics to Clinical Practice, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-45007-0. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. The use of diffuse laser photonic energy and indocyanine green photosensitiser as an adjunct to periodontal therapy. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 215, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. Photodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy in the General Dental Practice (Introduction). J. Laser Dent. 2009, 17, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Konopka, K.; Goslinski, T. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Hamblin, M. Antimicrobial Photosensitizers: Drug Discovery under the Spotlight. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 2159–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, P.; Kearns, D. Remarkable solvent effects on the lifetime of 1Δg oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 1029–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Kishen, A. Uptake pathways of anionic and cationic photosensitizers into bacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2009, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuzumi, S.; Ohkubo, K.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Pandey, R.; Zhan, R.; Kadish, K. Metal Bacteriochlorins Which Act as Dual Singlet Oxygen and Superoxide Generators. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 2738–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R.; Hasan, T. Photodynamic therapy: A new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004, 3, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, M.; Maisch, T.; Nonell, S.; Plaetzer, K.; Almeida, A.; Tegos, G.P.; Hamblin, M.R. Photoantimicrobials—Are we afraid of the light? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e49–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, H.; Ozcakir-Tomruk, C.; Tanalp, J.; Yilmaz, S. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry: A literature review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Savović, J.; Page, M.; Elbers, R.; Sterne, J. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Gaspirc, B.; Sculean, A. Clinical and microbiological effects of multiple applications of antibacterial photodynamic therapy in periodontal maintenance patients. A randomized controlled clinical study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, K.; Pavaskar, R.; Cappetta, E.; Drew, H. Effectiveness of Adjunctive Use of Low-Level Laser Therapy and Photodynamic Therapy After Scaling and Root Planing in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2019, 39, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Dehn, C.; Hinze, A.V.; Frentzen, M.; Meister, J. Indocyanine green-based adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for treating chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara Andere, N.M.R.; dos Santos, N.C.C.; Araujo, C.F.; Mathias, I.F.; Rossato, A.; de Marco, A.C.; Santamaria, M.; Jardini, M.A.N.; Santamaria, M.P. Evaluation of the local effect of nonsurgical periodontal treatment with and without systemic antibiotic and photodynamic therapy in generalized aggressive periodontitis. A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 24, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoro, L.H.; Assem, N.Z.; Longo, M.; Alves, M.L.F.; Duque, C.; Stipp, R.N.; Vizoto, N.L.; Garcia, V.G. Treatment of periodontitis in smokers with multiple sessions of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy or systemic antibiotics: A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 22, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segarra-Vidal, M.; Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Vallés, L.S.; López-Roldán, A.; Mauricio, M.D.; Aldasoro, M.; Alpiste-Illueca, F.; Vila, J.M. Effects of photodynamic therapy in periodontal treatment: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabenski, L.; Moder, D.; Cieplik, F.; Schenke, F.; Hiller, K.A.; Buchalla, W.; Schmalz, G.; Christgau, M. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy vs. local minocycline in addition to non-surgical therapy of deep periodontal pockets: A controlled randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 2253–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz Andrade, P.V.; Euzebio Alves, V.T.; de Carvalho, V.F.; De Franco Rodrigues, M.; Pannuti, C.M.; Holzhausen, M.; De Micheli, G.; Conde, M.C. Photodynamic therapy decrease immune-inflammatory mediators levels during periodontal maintenance. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurska, A.; Dolinska, E.; Pietruska, M.; Pietruski, J.K.; Dymicka, V.; Kemona, H.; Arweiler, N.B.; Milewski, R.; Sculean, A. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal treatment in conjunction with either systemic administration of amoxicillin and metronidazole or additional photodynamic therapy on the concentration of matrix metalloproteinases 8 and 9 in gingival crevicular fluid in patients with aggressive periodontitis. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.F.; Andrade, P.V.C.; Rodrigues, M.F.; Hirata, M.H.; Hirata, R.D.C.; Pannuti, C.M.; De Micheli, G.; Conde, M.C. Antimicrobial photodynamic effect to treat residual pockets in periodontal patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwaeli, H.A.; Al-Khateeb, S.N.; Al-Sadi, A. Long-term clinical effect of adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in periodontal treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Campanile, V.S.; Giannopoulou, C.; Campanile, G.; Cancela, J.A.; Mombelli, A. Single or repeated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as adjunct to ultrasonic debridement in residual periodontal pockets: Clinical, microbiological, and local biological effects. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsy, J.; Prasanth, C.S.; Baiju, K.V.; Prasanthila, J.; Subhash, N. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchesi, V.H.; Pimentel, S.P.; Kolbe, M.F.; Ribeiro, F.V.; Casarin, R.C.; Nociti, F.H.; Sallum, E.A.; Casati, M.Z. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of class II furcation: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balata, M.L.; de Andrade, L.P.; Santos, D.B.N.; Cavalcanti, A.N.; Tunes, U.d.R.; Ribeiro, E.d.P.; Bittencourt, S. Photodynamic therapy associated with full-mouth ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of severe chronic periodontitis: A randomized-controlled clinical trial. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2013, 21, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappuyns, I.; Cionca, N.; Wick, P.; Giannopoulou, C.; Mombelli, A. Treatment of residual pockets with photodynamic therapy, diode laser, or deep scaling. A randomized, split-mouth controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noro Filho, G.A.; Casarin, R.C.V.; Casati, M.Z.; Giovani, E.M. PDT in non-surgical treatment of periodontitis in HIV patients: A split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 2012, 44, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaker, A.M.; ArRejaie, A.S.; Alrabiah, M.; Al-Aali, K.A.; Mokeem, S.; Alasqah, M.N.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in open flap debridement in the treatment of peri-implantitis: A randomized controlled trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduljabbar, T. Effect of mechanical debridement with and without adjunct antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of peri-implant diseases in prediabetic patients. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 17, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, U.; Nardi, G.M.; Libotte, F.; Sabatini, S.; Palaia, G.; Grassi, F.R. The antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of peri-implantitis. Int. J. Dent. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Schär, D.; Wicki, B.; Eick, S.; Ramseier, C.A.; Arweiler, N.B.; Sculean, A.; Salvi, G.E. Anti-infective therapy of peri-implantitis with adjunctive local drug delivery or photodynamic therapy: 12-month outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2014, 25, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.S.; Vilas-Boas, L.; Tawil, P.Z. The effects of photodynamic therapy on postoperative pain in teeth with necrotic pulps. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miranda, R.G.; Colombo, A.P.V. Clinical and microbiological effectiveness of photodynamic therapy on primary endodontic infections: A 6-month randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcez, A.S.; Arantes-Neto, J.G.; Sellera, D.P.; Fregnani, E.R. Effects of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy and surgical endodontic treatment on the bacterial load reduction and periapical lesion healing. Three years follow up. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2015, 12, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurič, I.B.; Plečko, V.; Pandurić, D.G.; Anić, I. The antimicrobial effectiveness of photodynamic therapy used as an addition to the conventional endodontic re-treatment: A clinical study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2014, 11, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcez, A.S.; Nuñez, S.C.; Hamblin, M.R.; Suzuki, H.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photodynamic therapy associated with conventional endodontic treatment in patients with antibiotic-resistant microflora: A preliminary report. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1463–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, L.V.G.L.; Curylofo-Zotti, F.A.; Borsatto, M.C.; de Souza Salvador, S.L.; Valério, R.A.; Souza-Gabriel, A.E.; Corona, S.A.M. Influence of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in carious lesion. Randomized split-mouth clinical trial in primary molars. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargrizan, M.; Fekrazad, R.; Goudarzi, N.; Goudarzi, N. Effects of antibacterial photodynamic therapy on salivary mutans streptococci in 5- to 6-year-olds with severe early childhood caries. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornellas, P.O.; Antunes, L.S.; Motta, P.C.; Mendonça, C.; Póvoa, H.; Fontes, K.; Iorio, N.; Antunes, L.A.A. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as an Adjunct for Clinical Partial Removal of Deciduous Carious Tissue: A Minimally Invasive Approach. Photochem. Photobiol. 2018, 94, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Oliveira, C.; Longo, P.; Aranha, A.; Ramalho, K.; Mayer, M.; de Paula Eduardo, C. Randomized in vivo evaluation of photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy on deciduous carious dentin. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 108003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camila de Almelda, B.G.; Luz, M.A.; Simionato MR, L.; Ramalho, K.M.; Imparato, J.C.; Pinheiro, S.L. Clinical use of photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy for the treatment of deep carious lesions. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 088003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroozi, B.; Zomorodian, K.; Lavaee, F.; Zare Shahrabadi, Z.; Mardani, M. Comparison of the efficacy of indocyanine green-mediated photodynamic therapy and nystatin therapy in treatment of denture stomatitis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Senna, A.M.; Vieira, M.M.F.; Machado-de-Sena, R.M.; Bertolin, A.O.; Núñez, S.C.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photodynamic inactivation of Candida ssp. on denture stomatitis. A clinical trial involving palatal mucosa and prosthesis disinfection. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 22, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa da Mota, A.C.; França, C.M.; Prates, R.; Deana, A.M.; Costa Santos, L.; Lopes Garcia, R.; Leal Gonçalves, M.L.; Mesquita Ferrari, R.A.; Porta Santos Fernandes, K.; Kalil Bussadori, S. Effect of photodynamic therapy for the treatment of halitosis in adolescents—A controlled, microbiological, clinical trial. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, S.; Rehman, N.; Alrahlah, A.; Alamri, W.R.; Vohra, F. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy or low level laser therapy against steroid therapy in the treatment of erosive-atrophic oral lichen planus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, D.; Moussa, E.; Alnouaem, M. Evaluation of photodynamic therapy in treatment of oral erosive lichen planus in comparison with topically applied corticosteroids. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jajarm, H.H.; Falaki, F.; Sanatkhani, M.; Ahmadzadeh, M.; Ahrari, F.; Shafaee, H. A comparative study of toluidine blue-mediated photodynamic therapy versus topical corticosteroids in the treatment of erosive-atrophic oral lichen planus: A randomized clinical controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1475–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, C.N.; Keskin Tunc, S.; Erten, R.; Usumez, A. Clinical and histological evaluation of the efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy used in addition to antibiotic therapy in pericoronitis treatment. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M.; Anagnostaki, E.; Bordin-Aykroyd, S.; Lynch, E. Systematic Review of Delivery Parameters Used in Dental Photobiomodulation Therapy. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimofte, A.; Finlay, J.; Ong, Y.; Zhu, T. A quality assurance program for clinical PDT. In Optical Methods for Tumor Treatment and Detection: Mechanisms and Techniques in Photodynamic Therapy XXVII, 1st ed.; Kessel, D., Hassan, T., Eds.; SPIE Proceedings: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2018; p. 10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiniforush, N.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Shahabi, S.; Bahador, A. Clinical approach of high technology techniques for control and elimination of endodontic microbiota. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 6, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzavi, A.; Chinipardaz, Z.; Mousavi, M.; Fekrazad, R.; Moslemi, N.; Azaripour, A.; Bagherpasand, O.; Chiniforush, N. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using diode laser activated indocyanine green as an adjunct in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2016, 14, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegos, G.; Anbe, M.; Yang, C.; Demidova, T.; Satti, M.; Mroz, P.; Janjua, S.; Gad, F.; Hamblin, M. Protease-Stable Polycationic Photosensitizer Conjugates between Polyethyleneimine and Chlorin(e6) for Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Photoinactivation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostryukova, L.; Prozorovskiy, V.; Medvedeva, N.; Ipatova, O. Comparison of a new nanoform of the photosensitizer chlorin e6, based on plant phospholipids, with its free form. FEBS Open Biol. 2018, 8, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanaga, C.; Miessi, D.; Nuernberg, M.; Claudio, M.; Garcia, V.; Theodoro, L. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) with curcumin and LED, as an enhancement to scaling and root planing in the treatment of residual pockets in diabetic patients: A randomized and controlled split-mouth clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci Donato, H.; Pratavieira, S.; Grecco, C.; Brugnera-Júnior, A.; Bagnato, V.; Kurachi, C. Clinical Comparison of Two Photosensitizers for Oral Cavity Decontamination. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhóca, V.; Esteban Florez, F.; Corrêa, T.; Paolillo, F.; de Souza, C.; Bagnato, V. Oral Decontamination of Orthodontic Patients Using Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Blue-Light Irradiation and Curcumin Associated with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschoal, M.; Moura, C.; Jeremias, F.; Souza, J.; Bagnato, V.; Giusti, J.; Santos-Pinto, L. Longitudinal effect of curcumin-photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy in adolescents during fixed orthodontic treatment: A single-blind randomized clinical trial study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.; Paolillo, F.; Parmesano, T.; Fontana, C.; Bagnato, V. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy with Blue Light and Curcumin as Mouth Rinse for Oral Disinfection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, N.; Fontana, C.; Gerbi, M.; Bagnato, V. Overall-Mouth Disinfection by Photodynamic Therapy Using Curcumin. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2012, 30, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterenborg, H.; van Veen, R.; Aans, J.B.; Amelink, A.; Robinson, D.J. Light Dosimetry for Photodynamic Therapy: Basic Concepts. In Handbook of Photomedicine, 1st ed.; Hamblin, M., Huang, Y., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; p. 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, C.P.; Garcez, A.S.; Núñez, S.C.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Hamblin, M.R. Real-time evaluation of two light delivery systems for photodynamic disinfection of Candida albicans biofilm in curved root canals. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, A.S.; Hamblin, M.R. Methylene Blue and Hydrogen Peroxide for Photodynamic Inactivation in Root Canal—A New Protocol for Use in Endodontics. Eur. Endod. J. 2017, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, L.H.; Simões Ribeiro, M.; Kato, I.T.; Núñez, S.C.; Prates, R.A. Evaluation of red light scattering in gingival tissue—In vivo study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzler, J.-S.; Böcher, S.; Frankenberger, R.; Braun, A. Feasibility of transgingival laser irradiation for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 28, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y.; Hayashi, J.I.; Fujimura, T.; Iwamura, Y.; Yamamoto, G.; Nishida, E.; Ohno, T.; Okada, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. New irradiation method with indocyanine green-loaded nanospheres for inactivating periodontal pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, J.C. Light Dosimetry for Photodynamic Therapy: Basic Concepts. In Handbook of Photomedicine, 1st ed.; Hamblin, M., Huang, Y., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; p. 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chiang, L.; Hamblin, M. Photodynamic therapy with fullerenesin vivo: Reality or a dream? Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 1813–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareliotis, G.; Liossi, S.; Makropoulou, M. Assessment of singlet oxygen dosimetry concepts in photodynamic therapy through computational modeling. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekrazad, R.; Khoei, F.; Hakimiha, N.; Bahador, A. Photoelimination of Streptococcus mutans with two methods of photodynamic and photothermal therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2013, 10, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).