Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

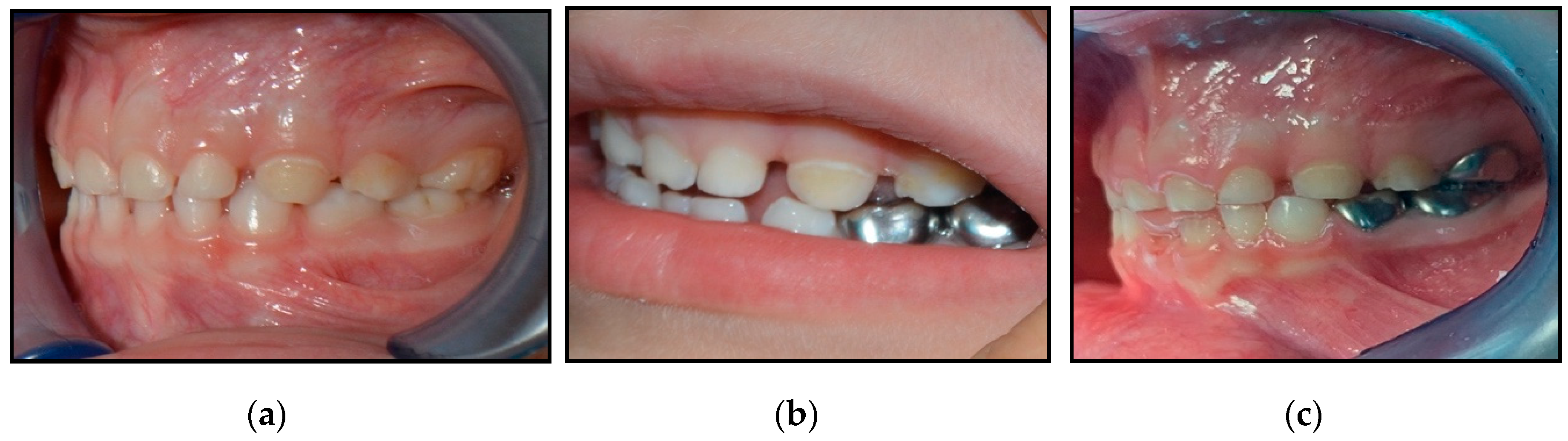

3.1. Description of the Hall Technique

3.2. Indications and Contraindications of the Hall Technique

3.3. Advantages of the Hall Technique

3.4. Concerns of the Hall Technique

3.5. Hall Technique Versus Traditional Crown Preparation

Success Versus Failure

3.6. Hall Technique Versus Other Restorations or Non-Restorative Approach

3.6.1. Success Versus Failure

3.6.2. Cost-Effectiveness

3.7. Preference and Acceptability of the Hall Technique

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | complete caries excavation and compomer restoration |

| ECC | early childhood caries |

| GDPs | general dental practitioners |

| GIC | glass ionomer cement |

| HT | Hall technique |

| NRCC | non-restorative cavity control |

| NRCT | nonrestorative caries treatment |

| OVDs | occlusal vertical dimensions |

| PMCs | preformed metal crowns |

| SSCs | stainless steel crowns |

| TMJ | temporomandibular joint |

References

- Gaidhane, A.M.; Patil, M.; Khatib, N.; Zodpey, S.; Zahiruddin, Q.S. Prevalence and determinant of early childhood caries among the children attending the Anganwadis of Wardha district, India. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2013, 24, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Congiu, G.; Campus, G.; Luglie, P.F. Early childhood caries (ECC) prevalence and background factors: A review. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2014, 12, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.I.; Lim, S.; Sohn, W.; Willem, J.M. Determinants of early childhood caries in low-income African American young children. Pediatr. Dent. 2008, 30, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- SIGN. Preventing Dental Caries in Children at High Caries Risk: Targeted Prevention of Dental Caries in the Permanent Teeth of 6–16 Year Olds Presenting for Dental Care. Available online: https://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item2491/2234.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Macpherson, L.M.; Pine, C.M.; Tochel, C.; Burnside, G.; Hosey, M.T.; Adair, P. Factors influencing referral of children for dental extractions under general and local anaesthesia. Community Dent. Health 2005, 22, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, I.; Hiraishi, N.; Duangthip, D.; Mei, M.; Lo, E.; Chu, C. Clinical Trials of Silver Diamine Fluoride in Arresting Caries among Children: A Systematic Review. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2016, 1, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tickle, M.K.; Milsom, K.M.; King, D.; Kearney-Mitchell, P.; Blinkhorn, A. The fate of the carious primary teeth of children who regularly attend the general dental service [comment]. Br. Dent. J. 2002, 192, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotland’s National Dental Inspection Programme 2003. Available online: http://www.dundee.ac.uk/ndip/index.htm (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- O’Brien, M. Children’s Dental Health in the United Kingdom. Available online: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/3045748 (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Milsom, K.; Tickle, M.; Blinkhorn, A. Dental pain and dental treatment of young children attending the general dental service. Br. Dent. J. 2002, 192, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayle, S. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry. Stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. Faculty of Dental Surgery, Royal College of Surgeons. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 1999, 9, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, A.G.; Pilkington, L.; Milsom, K.M.; Blinkhorn, A.S.; Tickle, M. General dental practitioners’ views on the use of stainless steel crowns to restore primary molars. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 199, 453–455; discussion 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, N.P.; Evans, D.J.; Stirrups, D.R. Sealing caries in primary molars: Randomized controlled trial—5-year results. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, N.P.; Stirrups, D.R.; Evans, D.J.; Hall, N.; Leggate, M. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice: A retrospective analysis. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 200, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, E.A. How ‘clean’ must a cavity be before restoration? Caries Res. 2004, 38, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddell, A.; Locker, D. Changes in levels of dental anxiety as a function of dental experience. Behav. Modif. 2000, 24, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggal, M.S.; Nooh, A.; High, A. Response of the primary pulp to inflammation: A review of the Leeds studies and challenges for the future. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2002, 3, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Torabzadeh, H.; Asgary, S. Indirect pulp therapy in a symptomatic mature molar using calcium enriched mixture cement. J. Conserv. Dent. 2013, 16, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts, D.; Lamont, T.; Innes, N.P.; Kidd, E.; Clarkson, J.E. Operative caries management in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, N.P.; Evans, D.J.; Hall, N. The Hall Technique for managing carious primary molars. Dent. Update 2009, 36, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.W., Jr.; Sarver, D.M. Contemporary Orthodontics, 4th ed.; Mosby, Elsevier Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2007; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, N.P.; Evans, D.J.; Stirrups, D.R. The Hall Technique; a randomized controlled clinical trial of a novel method of managing carious primary molars in general dental practice: Acceptability of the technique and outcomes at 23 months. BMC Oral Health 2007, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, A. The Hall technique is an effective treatment option for carious primary molar teeth. Evid.-Based Dent. 2008, 9, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.H.; Fontana, M.; LaQuia, A.; Jeffrey, A.P.; Jeffrey, A.D. The success of stainless steel crowns placed with the Hall technique. JADA 2014, 145, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Krois, J.; Robertson, M.; Splieth, C.; Santamaria, R.; Innes, N. Cost-effectiveness of the Hall Technique in a Randomized Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 98, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendicke, F.; Stolpe, M.; Innes, N.P. Conventional treatment, Hall Technique or immediate pulpotomy for carious primary molars: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, J.A.; Feigal, R.J.; Till, M.J.; Hodges, J.S. Parental attitudes on restorative materials as factors influencing current use in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr. Dent. 2009, 31, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van der Zee, V.; van Amerongen, W.E. Short communication: Influence of preformed metal crowns (Hall technique) on the occlusal vertical dimension in the primary dentition. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2010, 11, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, E.H.; Baker, I.M. The skeletodental adaptations in deep bite correction. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1991, 100, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sehaibany, F.; White, G. Posterior bite raising effect on the length of the ramus of the mandible in primary anterior crossbite: Case report. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 1996, 21, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, F. TMD and occlusion part II. Damned if we don’t? Functional occlusal problems: TMD epidemiology in a wider context. Br. Dent. J. 2007, 202, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, F.; Abdelazeem, N.; Salah, I.; Mirghani, Y.; Wong, F. A randomized clinical trial comparing Hall vs. conventional technique in placing preformed metal crowns from Sudan. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.P.; Sheiham, A. A clinical comparison of non-traumatic methods of treating dental caries. Int. Dent. J. 1994, 44, 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, N.S.; Coll, J.A.; Kuwabara, A.; Shelton, P. Success rates of formocresol pulpotomy and indirect pulp therapy in the treatment of deep dentinal caries in primary teeth. Pediatr. Dent. 2000, 22, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, C.C.; Baratieri, L.N.; Perdigao, J.; Baratieri, N.; Ritter, A. A clinical, radiographic, and scanning electron microscopic evaluation of adhesive restorations on carious dentin in primary teeth. Quintessence Int. Dent. J. 1999, 30, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.I.; Evans, D.J.P.; Blackwell, A. Partial caries removal and cariostatic materials in carious primary molar teeth: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 197, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, B.; Dummer, P.; Dunstan, F. How long do fillings last? Evid.-Based Dent. 2002, 3, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, B.L.; Evans, D.J. Restoration of class II cavities in primary molar teeth with conventional and resin modified glass ionomer cements: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2007, 8, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, R.M.; Innes, N.P.; Machiulskiene, V.; Evans, D.J.; Splieth, C.H. Caries Management Strategies for Primary Molars. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, M.; Silva, L.; Ferreira, D.; Barja-Fidalgo, F.; Fonseca-Gonçalves, A. Aesthetic perception, acceptability and satisfaction in the treatment of caries lesions with silver diamine fluoride: A scoping review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 29, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Petrou, S.; Carswell, C.; Moher, D.; Greenberg, D.; Augustovski, F.; Briggs, A.; Mauskopf, J.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013, 25, f1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Krois, J.; Splieth, C.; Innes, N.; Robertson, M.; Schmoeckel, J.; Santamaria, R. Cost-effectiveness of managing cavitated primary molar caries lesions: A randomized trial in Germany. J. Dent. 2018, 78, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, R.; Holmgren, C.; Mulder, J.; Lama, D.; Walker, D.; van Palenstein Helderman, W. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for arresting caries treatment. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumans, C.; Veerkamp, J.; Aartman, I.H. Dental anxiety and behavioural problems: What is their influence on the treatment plan? Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2004, 5, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- van Bochove, J.A.; van Amerongen, W.E. The influence of restorative treatment approaches and the use of local analgesia, on the children’s discomfort. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2006, 6, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, R.; Innes, N.; Machiulskiene, V.; Evans, D.; Alkilzy, M.; Splieth, C. Acceptability of different caries management methods for primary molars in a RCT. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 25, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindelan, S.; Day, P.; Nichol, R.; Willmott, N.; Fayle, S. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008, 18, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G. A Change in Practice Protocol: Preformed Metal Crowns for Treating Non-Infected Carious Primary Molars in a General Practice Setting; A Service Evaluation. Prim. Dent. J. 2015, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.A.; Bark, J.E.; Sherriff, A.; Macpherson, L.M.; Cairns, A. Use of the ‘Hall technique’ for management of carious primary molars among Scottish general dental practitioners. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 12, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.I. Short communication: A pan-European comparison of the management of carious primary molar teeth by postgraduates in paediatric dentistry. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, Y.; Janal, M.; Hamilton, D.; Niederman, R. Parental perceptions and acceptance of silver diamine fluoride staining. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 510–518.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indications of the Hall Technique |

|---|

|

| Contraindications of the Hall Technique |

| Advantages of the Hall Technique |

|---|

|

| Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Success |

|

| Minor Failure |

|

| Major Failure |

|

| Caries Management Approaches | Success Rate | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Hall Technique | 94.5% [32] | 1 year [32] |

| 97% [24] | 15 months [24] | |

| 73.4% [14] | 3 years [14] | |

| 94% [24] | 53 months [24] | |

| 67.6% [14] | 5 years [14] | |

| Traditional Crown Preparation | 96% [32] | 1 year [32] |

| Composite | 78% [37] | 3 years [37] |

| Glass Ionomer | 65% [37] | 3 years [37] |

| 32% [37] | 5 years [37] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altoukhi, D.H.; El-Housseiny, A.A. Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8010011

Altoukhi DH, El-Housseiny AA. Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature. Dentistry Journal. 2020; 8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltoukhi, Doua H., and Azza A. El-Housseiny. 2020. "Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature" Dentistry Journal 8, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8010011

APA StyleAltoukhi, D. H., & El-Housseiny, A. A. (2020). Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature. Dentistry Journal, 8(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8010011