Intentional Tooth Replantation: Current Evidence and Future Research Directions for Case Selection, Extraction Approaches, and Post-Operative Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

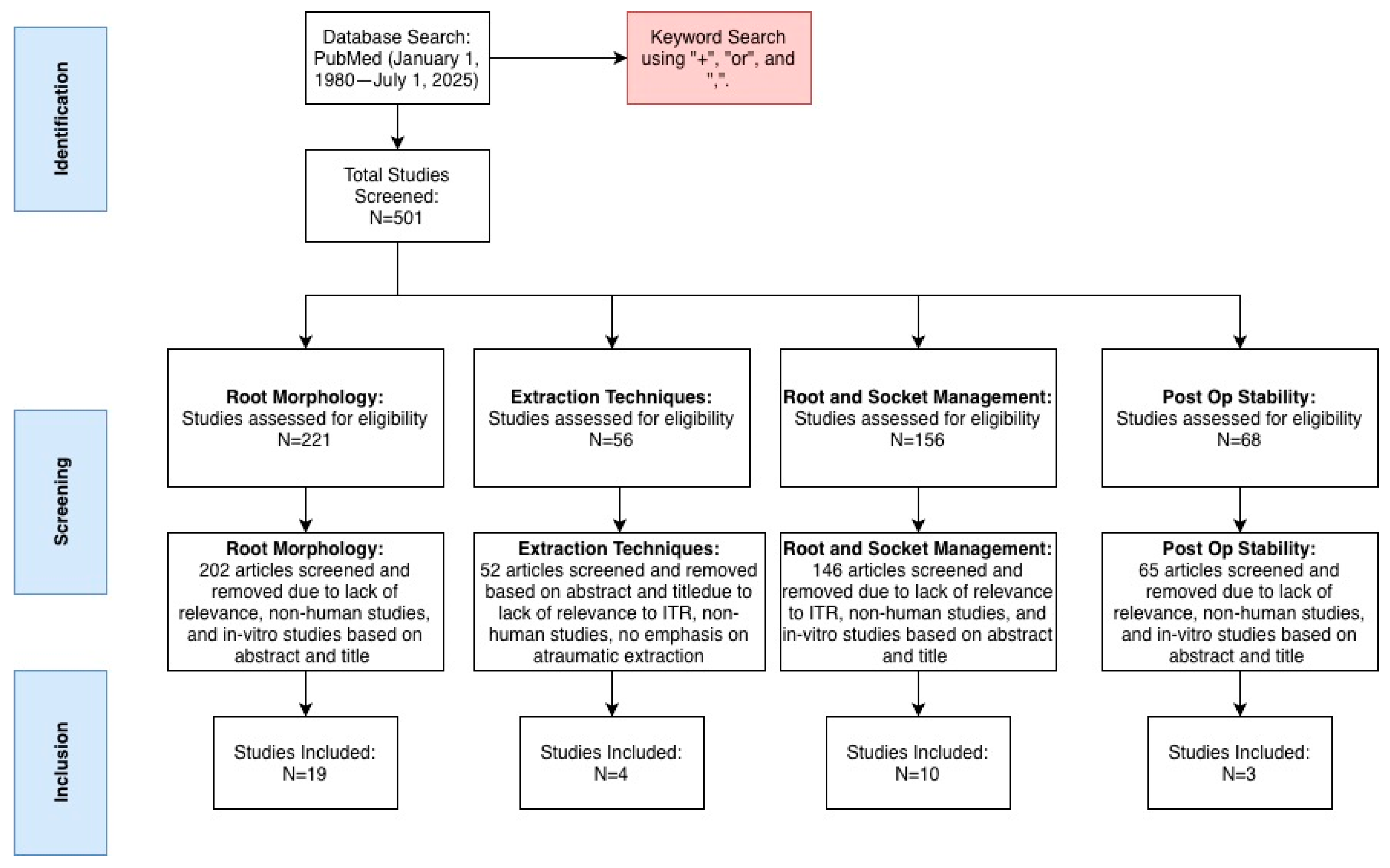

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Keywords: intentional tooth replantation, tooth auto transplantation, apicoectomy, endodontic microsurgery, extraction, flap elevation, sectioning, socket management, furcation management, root surface treatment, interradicular bone preservation

- Time period: 1 January 1980–1 July 2025

- Articles, more specifically case reports and human clinical trials/case studies, that pertained to root anatomy, root canal anatomy, oral surgery techniques, atraumatic extraction techniques, geographical discrepancies in root systems, PDL preservation, and splinting

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Articles in languages other than English

- Animal studies and in vitro studies

- Studies that were not related to the topic at hand (for example, avulsed teeth due to trauma were excluded when discussing post op stability)

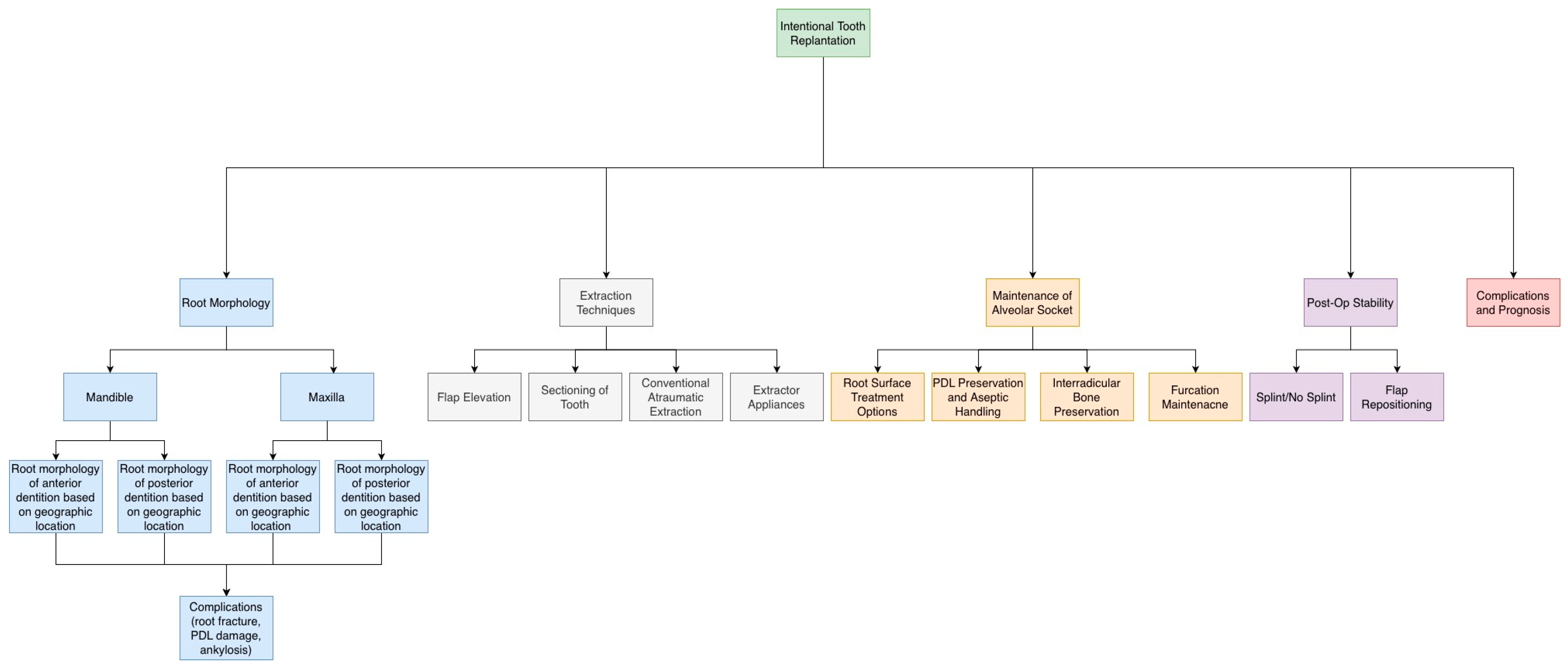

3. Morphological Variations in Root and Root Canal Systems

4. Extraction Techniques and Their Limitations Within ITR

5. Cleaning and Debridement of Root and Socket

6. Postoperative Stability

7. Complications and Prognosis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Z.; Huang, D.; Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Qiu, L.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Expert consensus on intentional tooth replantation. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainkar, A. A Systematic Review of the Survival of Teeth Intentionally Replanted with a Modern Technique and Cost-effectiveness Compared with Single-tooth Implants. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1963–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Ling, J.; Bian, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Ye, L.; et al. Expert consensus on difficulty assessment of endodontic therapy. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotino, G.; Abella Sans, F.; Bastos, J.V.; Nagendrababu, V. Effectiveness of intentional replantation in managing teeth with apical periodontitis: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Arx, T. Apical surgery: A review of current techniques and outcome. Saudi Dent. J. 2011, 23, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öğütlü, F.; Karaca, İ. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Apical Surgery: A Clinical Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2018, 17, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.E.; Kim, J.; Wu, Y.; Alzwaideh, R.; McGowan, R.; Sigurdsson, A. Outcomes of primary root canal therapy: An updated systematic review of longitudinal clinical studies published between 2003 and 2020. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.W.; Gutmann, J.L.; Solomon, E.S.; Rakusin, H. A clinical radiographic retrospective assessment of the success rate of single-visit root canal treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2004, 37, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Lee, S. Survival rate of a C-shaped canal after intentional tooth replantation: A study of 41 cases. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1320–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indications for Replantation and Recommended Techniques—American Association of Endodontists. Available online: https://www.aae.org/specialty/indications-replantation-recommended-techniques/ (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Plotino, G.; Abella Sans, F.; Duggal, M.S.; Grande, N.M.; Krastl, G.; Nagendrababu, V.; Gambarini, G. European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: Surgical Extrusion, Intentional Replantation and Tooth Autotransplantation. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, B.D. Intentional Replantation Techniques: A Critical Review. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertucci, F.J. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 58, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, C.A.; Marceliano-Alves, M.F.; Gomes, I.L.; Provenzano, J.C.; Alves, F.R.F. Natural canal deviation and dentin thickness of mesial root canals of mandibular first molars assessed by microcomputed tomography. Braz. Dent. J. 2024, 35, e245648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcić, A.; Jukić, S.; Brzović, V.; Miletić, I.; Pelivan, I.; Anić, I. Prevalence of root dilaceration in adult dental patients in Croatia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 102, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miloglu, O.; Cakici, F.; Caglayan, F.; Yilmaz, A.B.; Demirkaya, F. The prevalence of root dilacerations in a Turkish population. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2010, 15, e441–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebi, S.; Razavian, A.; Maddahi, N.; Asheghi, B.; Zangooei Booshehri, M. Evaluation of Root Dilaceration in Permanent Anterior and Canine Teeth in the Southern Subpopulation of Iran Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. J. Dent. 2023, 24, 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Pei, F.; Liu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, T.; Gu, Y. A micro–computed tomographic analysis of the root canal systems in the permanent mandibular incisors in a Chinese population. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Dai, Y.; Yan, Z.; You, Y.; Wu, B.; Lu, B. Morphological analysis of anterior permanent dentition in a Chinese population using cone-beam computed tomography. Head Face Med. 2023, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.; Sudhanva, M.E.; Rangappa, A.; Rangaswamy, V.; Murthy, C.S.; Kumar, N.N. Radicular Dentin Thickness and Root Canal Morphology of Mandibular Incisors in Indian Subpopulation Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography. Cureus 2024, 16, e73355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kinani, M.A.A.; Al-Shameri, B.H.H.; Al-Hamzi, M.A.A.; Al-Kholani, A.I.; Alnesairy, A.M.; Saber, N.H.; Issa, A.A.A. Root and canal morphology of permanent maxillary and mandibular canines in a sample of Yemeni population using cone-beam computed tomography. J. Clin. Res. Rep. 2024, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoye, C.I.; Jafarzadeh, H. Dilaceration among Nigerians: Prevalence, distribution, and its relationship with trauma. Dent. Traumatol. 2009, 25, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, C.M.R.; Rabelo, L.E.G.; Estrela, C.R.A.; Guedes, O.A.; Silva, B.S.F.; Estrela, C. Evaluation of Apical Root Morphology of Maxillary Incisors Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Brazilian Subpopulation: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2021, 15, ZC23–ZC26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah Hasan, H.; Al-Talabani, S.Z.; Hamad Ali, S.; Yalda, F.A.; Chawshli, O.F.; Kolemen, A.; Elgizawy, A.E.S.; Mostafa, O.Y. Prevalence and distribution pattern of dilacerated tooth among orthodontic patients using cone-beam computed tomography: A prospective multicenter study. Int. J. Orthod. Rehabil. 2023, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sheikh, H.M.; Al Ankily, M.; Shamel, M.; Massieh, C.M. Facial teeth dimensions and crown–root ratio in Egyptian population: Cross-sectional CBCT analysis. Al-Azhar J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 28, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llena, C.; Fernandez, J.; Ortolani, P.S.; Forner, L. Cone-beam computed tomography analysis of root and canal morphology of mandibular premolars in a Spanish population. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2014, 44, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsypremila, G.; Vinothkumar, T.S.; Kandaswamy, D. Anatomic symmetry of root and root canal morphology of posterior teeth in Indian subpopulation using cone beam computed tomography: A retrospective study. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 9, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheghi, B.; Sahebi, S.; Zangooei Booshehri, M.; Sheybanifard, F. Evaluation of Root Dilaceration by Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Iranian South Subpopulation: Permanent Molars. J. Dent. 2022, 23, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Fan, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Gu, Y. A micro-computed tomographic study of the anatomic danger zone in mesial roots of permanent mandibular first and second molars. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataer, M.; Abulizi, A.; Jumatai, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. C-shaped canal configuration in mandibular second molars of a selected Uyghur adults in Xinjiang: Prevalence, correlation, and differences of root canal configuration using cone-beam computed tomography. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano-Caldera, M.; Mejia-Cardona, J.L.; Blanco-Uribe, M.P.; Chaverra-Mesa, E.C.; Rodríguez-Lezama, D.; Parra-Sánchez, J.H. Fused roots of maxillary molars: Characterization and prevalence in a Latin American sub-population: A cone beam computed tomography study. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2019, 44, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, L.; Yang, D. Analysis of Root Canal Curvature and Root Canal Morphology of Maxillary Posterior Teeth in Guizhou, China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e928758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Ren, J.; Zou, L. CBCT evaluation of root canal morphology and anatomical relationship of root of maxillary second premolar to maxillary sinus in a western Chinese population. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narendar, R.; Balakrishnan, G.; Kavin, T.; Venkataraman, S.; Altaf, S.K.; Gokulanathan, S. Incidence of Risk and Complications Associated with Orthodontic Therapeutic Extraction. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2017, 9, S201–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Q. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation: A review of current evidence on anatomical factors and a decision tree. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Han, J.J. Risk factors for inferior alveolar nerve injury associated with implant surgery: An observational study. J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 20, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muska, E.; Walter, C.; Knight, A.; Taneja, P.; Bulsara, Y.; Hahn, M.; Desai, M.; Dietrich, T. Atraumatic vertical tooth extraction: A proof of principle clinical study of a novel system. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 116, e303–e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.P.; Kurylo, M.P.; Fong, T.K.; Lee, S.S.; Wagner, H.D.; Ryder, M.I.; Marshall, G.W. The biomechanical characteristics of the bone-periodontal ligament-cementum complex. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6635–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.; Bulsara, Y.; Gorecki, P.; Dietrich, T. Minimally invasive vertical versus conventional tooth extraction: An interrupted time series study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanami, M.; Sugaya, T.; Gama, H.; Tsukuda, N.; Tanaka, S.; Kato, H. Periodontal healing after replantation of intentionally rotated teeth with healthy and denuded root surfaces. Dent. Traumatol. 2001, 17, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Arora, S.A.; Chhina, S.; Mathur, R.K. Bicuspidization—A case report. J. Dent. Spec. 2019, 7, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.J.; Shaikh, S.S.; Shaikh, S.Y.; Hussain, M.A. Inter radicular bone dimensions in primary stability of immediate molar implants—A cone beam computed tomography retrospective analysis. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, E. Clinical Outcomes after Intentional Replantation of Periodontally Involved Teeth. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, M.; Di Spirito, F.; Martina, S.; Sangiovanni, G.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Iandolo, A. Intentional Replantation of Single-Rooted and Multi-Rooted Teeth: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, B.; Demiralp, B.; Güncü, G.N.; Uyanik, M.O.; Cağlayan, F. Intentional replantation of a hopeless tooth with the combination of platelet rich plasma, bioactive glass graft material and non-resorbable membrane: A case report. Dent. Traumatol. 2007, 23, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, Y.; Yao, Q.T.; Wu, Y.H.; Li, S.H. Intentional replantation as the treatment of left mandibular second premolar refractory periapical periodontitis: A case report. Open Dent. J. 2024, 18, e18742106283909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.K.; Jibhkate, N.G.; Redij, S.A. Intentional replantation of failed root canal treated tooth. J. Interdiscip. Dent. 2024, 14, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Papanikolaou, N.; Coulthard, P.; Worthington, H.V. Enamel matrix derivative (Emdogain(R)) for periodontal tissue regeneration in intrabony defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD003875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, D.; Goyal, A.; Gauba, K. Delayed replantation of avulsed tooth with 15-hours extra-oral time: 3-year follow-up. Singap. Dent. J. 2014, 35, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Yan, W.; Yan, J.; Tong, W.; Chen, W.; Lin, Y. LPCGF and EDTA conditioning of the root surface promotes the adhesion, growth, migration and differentiation of periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Pires, M.D.; Baruwa, A.O.; Martins, J.N.R.; Ginjeira, A. Intentional replantation of severely compromised teeth. G. Ital. Di Endod. 2022, 36, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; Talebzadeh, B. Intentional replantation of a molar with several endodontic complications. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvivedi, A.; Murthy, S.I.; Akkulugari, V.; Ali, H. Surgical and visual outcomes of flap repositioning for various flap-related pathologies post laser in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK). Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzanich, D.; Rizzo, G.; Silva, R.M. Saving Natural Teeth: Intentional Replantation—Protocol and Case Series. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 2119–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Geographic Location | Number of Teeth Examined | Root Morphology Characteristics | Number of Roots | Mean Root Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malčić et al., 2006 [15] | Croatia | 12,392 | Central Incisor: 1.7% dilacerated Lateral Incisor: 0% dilacerated Canine: 1.2% dilacerated | All mandibular anterior dentition had 1 root | Not reported |

| Miloglu et al., 2010 [16] | Turkey | 6386 | Central Incisor: 0% dilacerated Lateral Incisor: 0% dilacerated Canine: 1.3% dilacerated | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sahebi et al., 2023 [17] | Iran | 1537 | Central Incisors: 4.9% dilacerated Lateral Incisors: 2.7% dilacerated Canine: 9.7% dilacerated Most frequent direction of dilaceration were distal, buccal, mesial, and lingual in that order 92.4% of dilacerations were mild (20–40°) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Tang et al., 2023 [18] Chen et al., 2023 [19] | China | 106 [18] 4309 [19] | No dilaceration data reported. Mandibular canines and lateral incisors displayed root furcation:

| All incisors presented with one root | Central Incisor: 12.37 ± 1.24 mm Lateral Incisor: 11.09 ± 0.88 mm [15] Right Central Incisor: 12.22 ± 1.20 mm Left Central Incisor: 12.19 ±1.16 mm Right Lateral Incisor: 13.40 ± 1.27 mm Left Lateral Incisor: 13.36 ± 1.24 mm Right Canine: 15.40 ± 1.70 mm Left Canine: 15.55 ± 1.70 mm |

| Krishnan et al., 2024 [20] | India | 400 | Central Incisors: 3.5% distally curved, 0.5% buccally curved Lateral Incisors: 2.5% distally curved, 2% buccally curved, 0.5% mesially curved | Central Incisors: 100% one root Lateral Incisors: 100% one root | Central Incisors: 12.769 ± 1.128 mm Lateral Incisors: 13.044 ± 1.235 mm |

| Abdulsalam Ali Al-kinani et al., 2024 [21] | Yemen | 192 | Not reported | 1.5% of canines had 2 roots (♂) 2.5% of canines had 2 roots in (♀) | One rooted canine (♂): 16.2 ± 1.6 mm Two rooted canine (♂): 11.8 ± 2.3 mm lingual and buccal root One rooted canine (♀): 14.8 ± 2.2 mm Two rooted canine (♀): 13.3 ± 0.4 mm |

| Study | Geographic Location | Number of Teeth Examined | Root Morphology Characteristics | Number of Roots | Mean Root Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Udoye et al., 2009 [22] | Nigeria | 706 | Central Incisor: 0% dilacerated Lateral Incisor: 2.5% dilacerated Canine: 0% dilacerated * Females had greater predilections to dilacerations | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bernardes et al., 2021 [23] | Brazil | 400 | Apical root morphology central Incisor: 6.5% short, 49.5% blunt (rhomboid), 9.5% curved, 34.5% pipette shaped Apical root morphology lateral incisor: 2.5% short, 23.5% blunt (rhomboid), 55.5% curved, 18.5% pipette shaped [23] | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sahebi et al., 2023 [17] | Iran | 1537 | Central Incisor: 1.5% dilacerated Lateral Incisor: 7.1% dilacerated Canine: 9.8% dilacerated

| Not reported | Not reported |

| Chen et al., 2023 [19] | China | 4309 | No furcation observed in maxillary anterior teeth. | All maxillary anterior teeth had 1 root | Right Central Incisor: 13.39 ± 1.69 mm Left Central Incisor: 13.32 ± 1.74 mm Right Lateral Incisor: 13.48 ± 1.54 mm Left Lateral Incisor: 13.32 ± 1.74 mm Right Canine: 16.78 ± 1.94 mm Left Canine: 16.54 ± 2.11 mm |

| Hasan et al., 2023 [24] | Iraq | 389 patients where full dentition was examined | Central Incisor: 14.1% dilacerated, 100% of dilaceration was in apical 1/3 Lateral Incisor: 40.2% dilacerated, 67.5% of dilaceration was in apical 1/3, 32.5% in middle third Canine: 26.1% dilacerated, 100% of dilaceration in apical 1/3 | Not reported | Not reported |

| El Sheikh et al., 2025 [25] | Egypt | 600 patients where full dentition was examined | Not reported | Not reported | Right Canine: ♂: 14.28 ± 0.388 mm ♀: 13.98 ± 0.356 mm Left Canine: ♂: 14.05 ± 0.366 mm ♀: 14.03 ± 0.368 mm Left Lateral Incisor: ♂: 12.02 ± 0.215 mm ♀: 12.05 ± 0.184 mm Right Lateral Incisor: ♂: 12.32 ± 0.220 mm ♀: 12.17 ± 0.163 mm Right Central Incisor: ♂: 14.11 ± 0.465 mm ♀: 14.05 ± 0.384 mm Left Central Incisor: ♂: 14.37 ± 0.585 mm ♀: 13.94 ± 0.392 mm |

| Study | Geographic Location | Number of Teeth Examined | Root Morphology Characteristics | Number of Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llena et al., 2014 [26] | Spain | 126 | Mean length of first and second premolar roots in males was 16.05 mm and 14.91 mm in females (significant difference) First premolar: 34.2% had no root angulation, 9.6% had buccal angulation, 12.3% had lingual angulation, 13.7% had mesial angulation, and 30.1% had distal angulation Second premolar: 45.3% had no root angulation, 22.6% had buccal angulation, 7.5% had lingual angulation, 7.5% had mesial angulation, 7.0% had distal angulation | All mandibular premolars were single rooted |

| Felsypremila et al., 2015 [27] | India | 3015 | Bilateral anatomic symmetry was seen in 96.1% of mandibular first premolars 98.3% of mandibular second premolars had bilateral anatomic symmetry Bilateral anatomic symmetry was seen in 78.6% of mandibular first molars 82.1% of mandibular second molars had bilateral anatomic symmetry | Mandibular first premolar: 2% had 2 roots, 98% had 1 root Mandibular second premolar: 99.7% had 1 root, 0.3% had 2 roots Mandibular first molar: 5.7% had 3 roots, 93.6% had 2 roots, 0.7% had 1 root Mandibular second molar: 2.5% had 3 roots, 88.8% had 2 roots, and 8.7% had 1 root |

| Asheghi et al., 2022 [28] | Iran | 472 | 20.0% of mandibular first molars had dilaceration 15.3% of mandibular second molars had dilaceration | Not reported |

| Hasan et al., 2023 [24] | Iraq | 389 patients where full dentition was examined | First premolar: 0.0% dilaceration Second premolar: 6.8% dilaceration First molar: 6.8% dilaceration Second molar: 6.8% Second molars had 66.7% of dilacerations occurring in middle 1/3 and 33.3% in the apical 1/3 | Not reported |

| Tang et al., 2025 [29] | China | 110 | Average root length of 3 rooted first molars: 9.17 ± 1.40 mm Average root length of 2 rooted first molars: 9.68 ± 1.31 mm Average root length of 2 rooted second molars: 8.85 ± 1.37 mm All mesial roots curved severely (81.8%) or moderately (18.2%) towards the furcation side No straight roots observed All mesial roots except one exhibited distal concavities Mesial concavities only observed in 76.0% of first molars and 60% of second molars | 67% of mandibular first molars had 2 roots 33% of mandibular first molars had 3 roots 100% of mandibular second molars had 2 roots |

| Pataer et al., 2025 [30] | China | 1748 patients, specifically looking at patients with C-shape canal morphology | 12.8% of second molars had two separate divergent/parallel roots with clear trabeculae between them 40.5% of second molars had two separate converging roots with clear trabeculae between them Longitudinal grooves mainly located on the lingual surface | 10.2% of mandibular second molars had 1 root 34.7% of mandibular second molars had 2 roots 52.1% of mandibular second molars had 3 roots 3.0% of mandibular second molars had 4 roots |

| Study | Geographic Location | Number of Teeth Examined | Root Morphology Characteristics | Number of Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miloglu et al., 2010 [16] | Turkey | 6386 | First Premolar: 3.2% root dilaceration Second Premolar: 5.1% root dilaceration First Molar: 6.7% root dilaceration Second molar: 5.4% root dilaceration | Not reported |

| Felsypremila et al., 2015 [27] | India | 3015 | Tooth anatomic symmetry was seen in 81.5% of maxillary first premolars and 81.5% of maxillary second premolars Tooth anatomic symmetry was seen in 77.5% of mandibular first molars and 70.8% of mandibular second molars | Maxillary first premolar: 51.2% had 2 roots, 48.8% had 1 root Maxillary second premolar: 90.6% had 1 root, 9.4% had 2 roots Maxillary first molar: 0.5% had 4 roots, 96.8% had 3 roots, 2.7% had 2 roots Maxillary second molar: 1.1% had 4 roots, 80.3% had 3 roots, 8.9% had 2 roots, and 9.7% had 1 root |

| Marcano-Caldera et al., 2019 [31] | Colombia | 1359 CBCT scans | 43.2% of maxillary molars presented with some type of radicular fusion Root fusion was observed in 23.3% of first maxillary molars, 57.7% of second maxillary molars Type 3 fusion (DB root fused with palatal root) was most common in first maxillary molars Type 6 fusion (P, MB, and DB roots fused as a cone shaped root) was most common in second maxillary molars | Not reported |

| Qiao et al., 2021 [32] | China | 274 | Mean curvature of maxillary second premolar was higher than that of first premolar. All premolars had moderate curvature (5–20°) in mesiodistal and buccolingual directions MB1 and MB2 of maxillary first molars and MB2 of maxillary second molars showed severe bending (>20°) in mesiodistal directions | Not reported |

| Yan et al., 2021 [33] | China | 1118 | 56.4% if maxillary second premolars were curved. 44.2% of maxillary second premolars were moderately curved (10–25°) mesiodistally and 12.2% were severely curved mesiodistally (>25°) 29.5% of maxillary second premolars were also moderately curved buccopalatally and 11.4% were severely curved buccopalatally The mean distance from the root tip to the floor of the maxillary sinus was 2.47 ± 3.45 mm | 94.2% of maxillary second premolars had 1 root 5.8% of maxillary second premolars had 2 roots |

| Hasan et al., 2023 [24] | Iraq | 389 patients where full dentition was examined | First premolar: 6.5% dilaceration Second premolar: 0% dilaceration First molar: 0% dilaceration Second molar: 13.1% Second molars had 66.7% of dilacerations occurring in middle 1/3 and 33.3% in the apical 1/3 | Not reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shah, R.M.; Manders, T.; Romanos, G. Intentional Tooth Replantation: Current Evidence and Future Research Directions for Case Selection, Extraction Approaches, and Post-Operative Management. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010059

Shah RM, Manders T, Romanos G. Intentional Tooth Replantation: Current Evidence and Future Research Directions for Case Selection, Extraction Approaches, and Post-Operative Management. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Rahul Minesh, Thomas Manders, and Georgios Romanos. 2026. "Intentional Tooth Replantation: Current Evidence and Future Research Directions for Case Selection, Extraction Approaches, and Post-Operative Management" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010059

APA StyleShah, R. M., Manders, T., & Romanos, G. (2026). Intentional Tooth Replantation: Current Evidence and Future Research Directions for Case Selection, Extraction Approaches, and Post-Operative Management. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010059