From Thermal Springs to Saline Solutions: A Scoping Review of Salt-Based Oral Healthcare Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

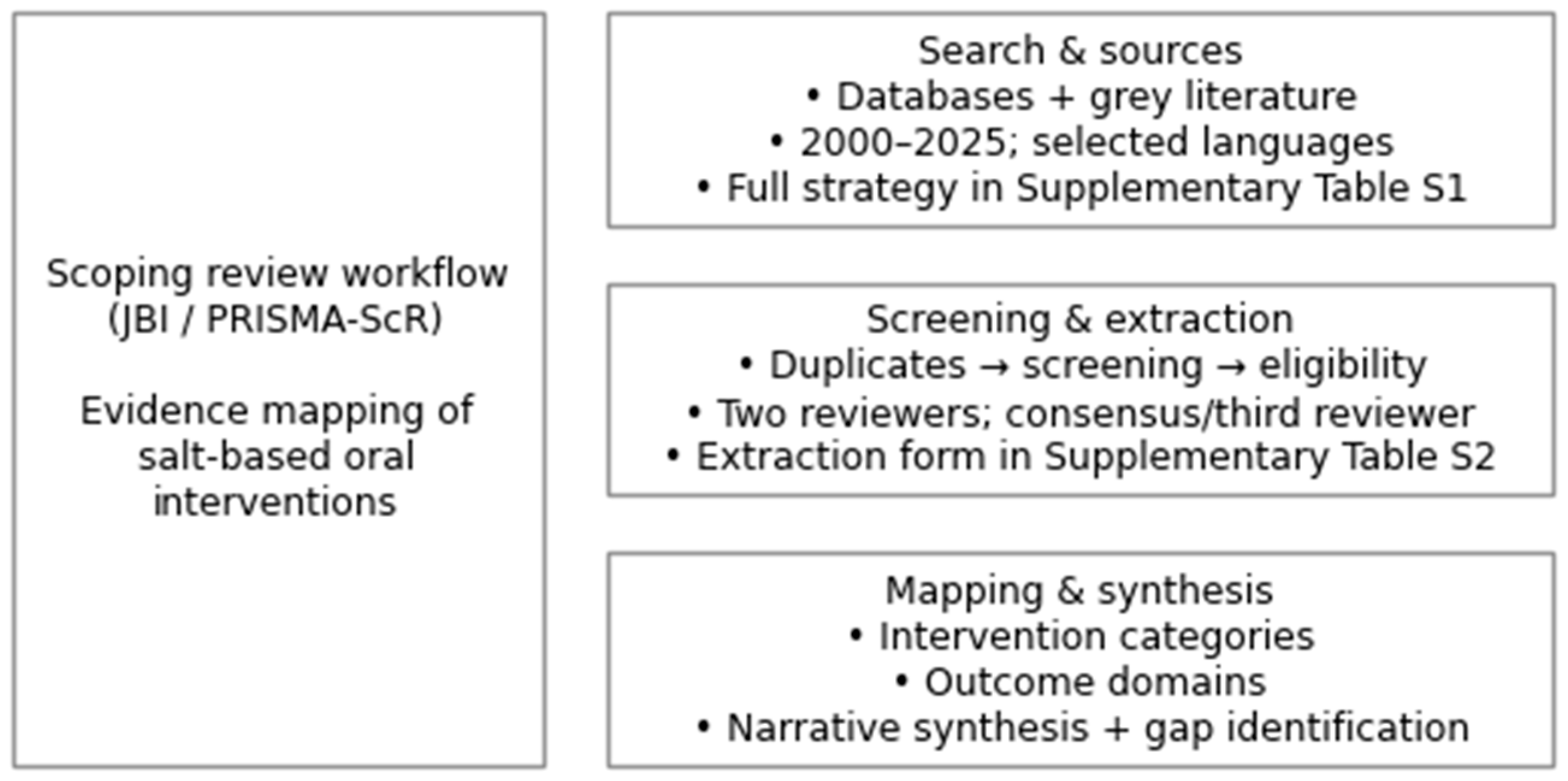

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

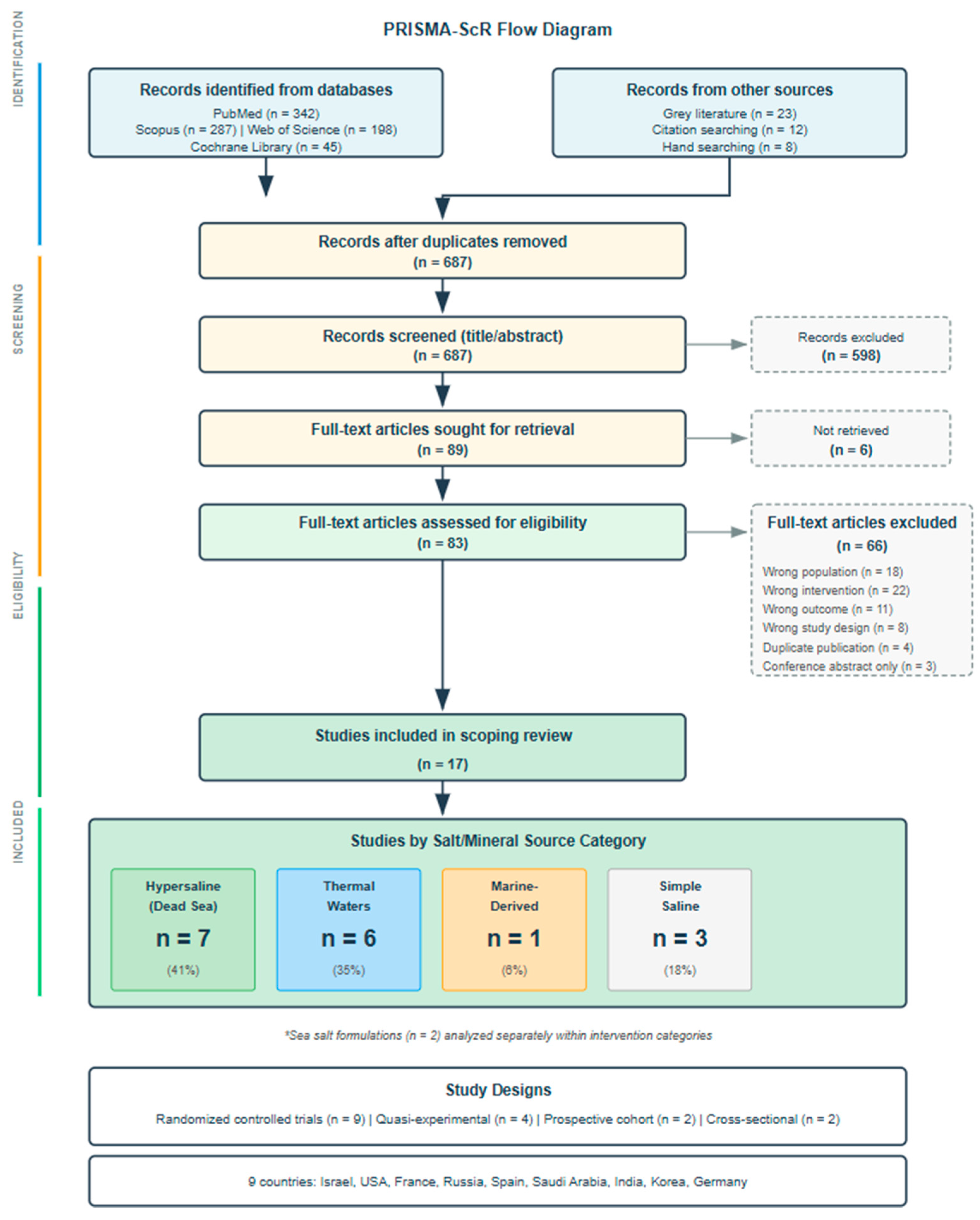

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

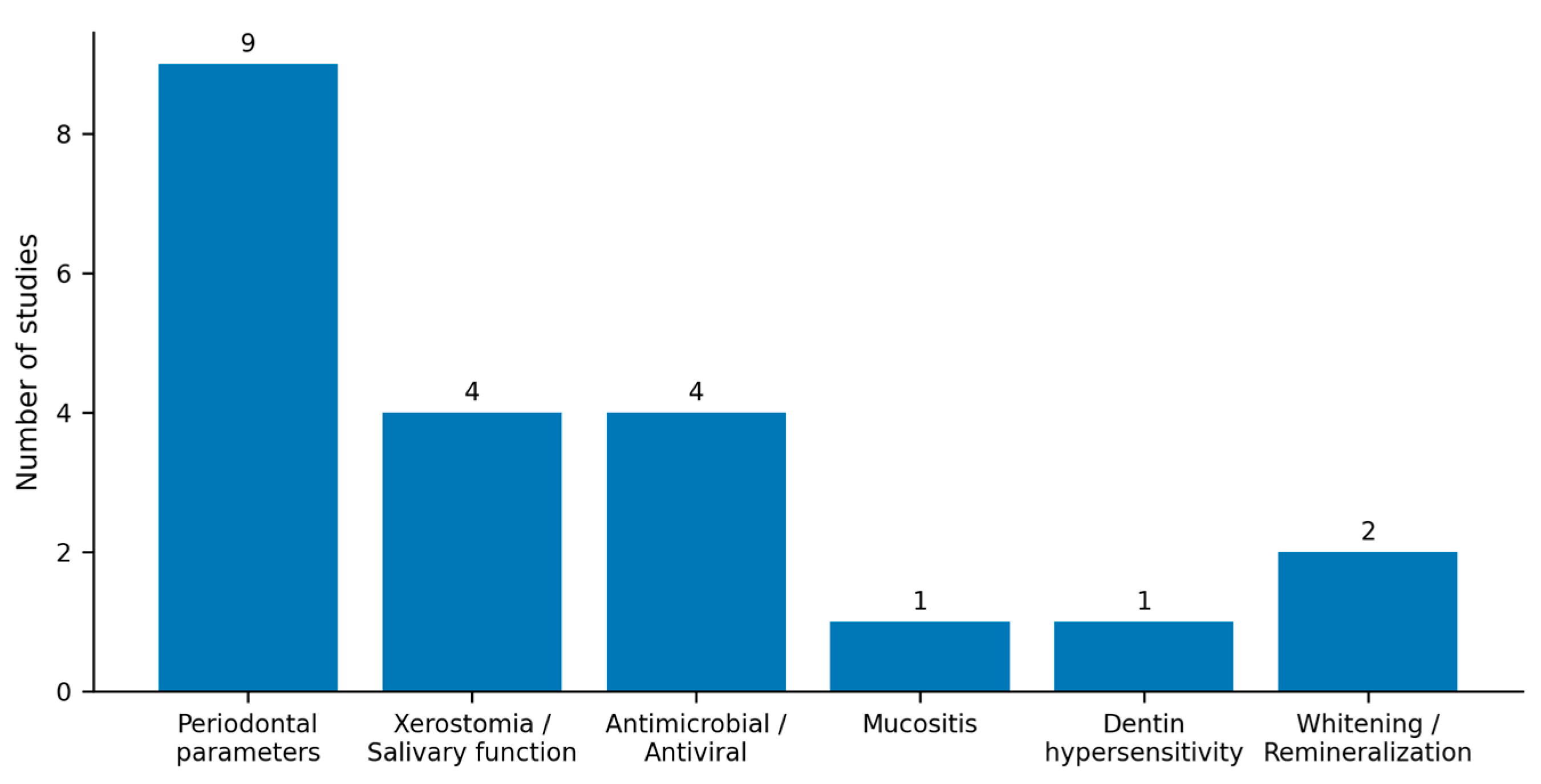

3.2. Outcomes and Comparators

3.3. Findings by Intervention Category

3.3.1. Hypersaline Dead Sea Derivatives

3.3.2. Thermal Mineral Waters

3.3.3. Simple Saline Solutions

3.3.4. Marine-Derived and Sea Salt Formulations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BI | Bleeding Index |

| CMC | Carboxymethylcellulose |

| DH | Dentin Hypersensitivity |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr Virus |

| HCMV | Human Cytomegalovirus |

| HSV-1 | Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| MGI | Modified Gingival Index |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| OHIP-14 | Oral Health Impact Profile 14 |

| OMD | Oral Mucosal Disease |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Oliveira, T.A.S.; Santiago, M.B.; Santos, V.H.P.; Silva, E.O.; Martins, C.H.G.; Crotti, A.E.M. Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils against Oral Pathogens. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.C.; Charles, C.H.; Qaqish, J.G.; Galustians, H.J.; Zhao, Q.; Kumar, L.D. Comparative effectiveness of an essential oil mouthrinse and dental floss in controlling interproximal gingivitis and plaque. Am. J. Dent. 2002, 15, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farah, C.S.; McIntosh, L.; McCullough, M.J. Mouthwashes. Aust. Prescr. 2009, 32, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.O.; Vasconcelos, C.C.; Lopes, A.J.; Cartágenes, M.S.; Filho, A.K.; do Nascimento, F.R.; Ramos, R.M.; Pires, E.R.; de Andrade, M.S.; Rocha, F.A.; et al. Candida infections and therapeutic strategies: Mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescos, R.; Ashworth, A.; Cutler, C.; Brookes, Z.L.S.; Belfield, L.; Rodiles, A.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Farnham, G.; Liddle, L.; Burleigh, M.; et al. Effects of Chlorhexidine mouthwash on the oral microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, V.; Haydar, S.M.; Pearl, V.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Ahluwalia, A. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 55, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Zarkadoulia, E.; Rafailidis, P.I. The therapeutic effect of balneotherapy: Evaluation of the evidence from randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.; Glenny, A.M.; Worthington, H.V.; Littlewood, A.; Clarkson, J.E.; McCabe, M.G. Interventions for preventing oral mucositis in patients with cancer receiving treatment: Oral cryotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, CD011552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumgalz, B.; Bury, R.; Treiner, C. Thermochemistry of natural hypersaline water sys-tems using the Dead Sea as a case. J. Solut. Chem. 1990, 19, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishcha, P.; Gertman, I.; Starobinets, B. Surface and Subsurface Heatwaves in the Hypersaline Dead Sea Caused by Severe Dust Intrusion. Hydrology 2025, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.F.; Michel, M.G.; Nadan, J.; Nowzari, H. The street children of Manila are affected by early-in-life periodontal infection: Description of a treatment modality: Sea salt. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim (1993) 2013, 30, 6–13, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.M. Bacterial responses to osmotic challenges. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015, 145, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, L.D.; den Hartog, G.; Ernst, P.B.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative stress resulting from helicobacter pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Isotopic composition of geothermal water and steam discharges. In Application of Geochemistry in Geothermal Reservoir Development; D’Amore, F., Ed.; UNITAR/UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, R.O.; Truesdell, A.H. An empirical Na-K-Ca geothermometer for natural waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1973, 37, 1255–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghersetich, I.; Freedman, D.; Lotti, T. Balneology today. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2000, 14, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurich, N.; Anastasia, M.K.; Grender, J.; Sagel, P. Tooth color change and tolerability evaluation of a hydrogen peroxide whitening strip compared to a strip, paste, and rinse regimen containing plant-based oils and Dead Sea salt. Am. J. Dent. 2023, 36, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Nowzari, H.; Wilder-Smith, P. Effects of mouthwash on oral cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus type-1. Adv. Clin. Med. Res. 2022, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowzari, H.; Tuan, M.C.; Jorgensen, M.; Michel, M.G.; Michel, J.F. Dead sea salt solution: Composition, lack of cytotoxicity and in vitro efficacy against oral leukotoxins, endotoxins and glucan sucrose. Insights Biol. Med. 2022, 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.; Ajdaharian, J. Effects of a novel mouthwash on plaque presence and gingival health. Dentistry 2017, 7, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Guirado, J.L.; Fernández Domínguez, M.; Aragoneses, J.M.; Martínez González, J.M.; Fernández-Boderau, E.; Garcés-Villalá, M.A.; Romanos, G.E.; Delgado-Ruiz, R. Evaluation of new seawater-based mouthrinse versus chlorhexidine 0.2% reducing plaque and gingivitis indexes. A randomized controlled pilot study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdaharian, J.; Takesh, T.; Anbarani, A.; Ho, J.; Wilder-Smith, P. Effects of a Novel Mouthwash on Dental Remineralization. Dentistry 2017, 7, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matceyevsky, D.; Hahoshen, N.Y.; Vexler, A.; Noam, A.; Khafif, A.; Ben-Yosef, R. Assessing the effectiveness of Dead Sea products as prophylactic agents for acute radiochemotherapy-induced skin and mucosal toxicity in patients with head and neck cancers: A phase 2 study. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 9, 439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.; Couto, P.; Viana, A.; Silva, F.; Correia, M.J. Unravelling the benefits of thermal waters enhancing oral health: A pilot study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpöz, E.; Çankaya, H.; Güneri, P.; Epstein, J.B.; Boyacioglu, H.; Kabasakal, Y.; Ocakci, P.T. Impact of Buccotherm® on xerostomia: A single blind study. Spec. Care Dent. 2015, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrinjar, I.; Vucicevic Boras, V.; Bakale, I.; Andabak Rogulj, A.; Brailo, V.; Vidovic Juras, D.; Alajbeg, I.; Vrdoljak, D.V. Comparison between three different saliva substitutes in patients with hyposalivation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumassian, M.G.; Toumassian, S.; Satygo, E.A. The effectiveness of oral hygiene products based on Castéra-Verduzan thermal water in patients with post-COVID syndrome. Clin. Dent. 2022, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novozhilova, N.; Andreeva, E.; Polyakova, M.; Makeeva, I.; Sokhova, I.; Doroshina, V.; Zaytsev, A.; Babina, K. Antigingivitis, Desensitizing, and Antiplaque Effects of Alkaline Toothpastes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.R.; Veras, K.; Hernández, M.; Hou, W.; Hong, H.; Romanos, G.E. Anti-inflammatory effect of salt water and chlorhexidine 0.12% mouthrinse after periodontal surgery: A randomized prospective clinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 4349–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravinth, V.; Aswath Narayanan, M.B.; Ramesh Kumar, S.G.; Selvamary, A.L.; Sujatha, A. Comparative evaluation of salt water rinse with chlorhexidine against oral microbes: A school-based randomized controlled trial. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2017, 35, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamdem, G.S.J.N.; Toukam, M.; Ntep, D.B.N.; Kwedi, K.G.G.; Brian, N.Z.; Fokam, S.T.; Messanga, C.B. Comparison of the effect of saline mouthwash versus chlorhexidine on oral flora. Adv. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 6, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.; Tovar, E.; Zlatnik, T.; Karunanayake, C. Efficacy of a rinse containing sea salt and lysozyme on biofilm and gingival health in a group of young adults: A pilot study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 15, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Signorini, L.; Saini, R.; Scacco, S.; Gnoni, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; De Vito, D.; Santacroce, L.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Efficacy of Sea Salt-Based Mouthwash and Xylitol in Improving Oral Hygiene among Adolescent Population: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, A.; Karagülle, M.; Bender, T.; Karagülle, M. Balneotherapy in Osteoarthritis: Facts, Fiction and Gaps in Knowledge. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 9, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti, S.; Luciano, M.A.; Megna, M.; Annunziata, M.C.; Napolitano, M.; Patruno, C.; Scala, E.; Colicchio, R.; Pagliuca, C.; Salvatore, P.; et al. The Role of Thermal Water in Chronic Skin Diseases Management: A Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, A.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Boers, M.; Cardoso, J.R.; Lambeck, J.; de Bie, R.; de Vet, H.C. Balneotherapy for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagülle, M.; Karagülle, M.Z.; Karagülle, O.; Dönmez, A.; Turan, M. A 10-day course of SPA therapy is beneficial for people with severe knee osteoarthritis. A 24-week randomised, controlled pilot study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seite, S. Thermal waters as cosmeceuticals: La Roche-Posay thermal spring water example. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 6, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lile, I.E.; Hajaj, T.; Veja, I.; Hosszu, T.; Vaida, L.L.; Todor, L.; Stana, O.; Popovici, R.-A.; Marian, D. Comparative Evaluation of Natural Mouthrinses and Chlorhexidine in Dental Plaque Management: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Water Type | Study Design | Population/Sample | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HYPERSALINE WATER STUDIES (DEAD SEA REGION) | |||||||

| Gurich et al. [19] | Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | Parallel-group double-blind RCT | 50 adults (18–62 years) | Natural whitening regimen with Dead Sea salt-based products (strips, toothpaste, mouthwash) | Conventional peroxide-based whitening system | Objective tooth color assessment at 7, 10, and 14 days | No significant whitening with Dead Sea regimen; conventional peroxide-based treatment achieved measurable color improvement. |

| Nowzari et al., 2022a [20] | Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | Double-blind controlled trial | 30 adults (25–35 years) with gingivitis and detectable oral viruses | Oral rinse containing Dead Sea salts used twice daily over 8-week period | Control rinse (distilled water) | Salivary detection of herpes viruses (HSV-1, HCMV, EBV) | Significant reduction of HSV-1, HCMV, and EBV viral loads vs. control (p < 0.001). |

| Nowzari et al., 2022b [21] | Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | Laboratory efficacy study | Mouse fibroblast cell cultures | Dead Sea salt solution exposure at therapeutic concentrations | Standard culture conditions | Cell viability and bacterial toxin neutralization | No cytotoxicity; significant reduction of leukotoxin (−84%), endotoxin (−40%), and glucan enzyme (−90%). |

| Rodriguez & Ajdaharian [22] | Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | Three-arm controlled trial | 10 healthy volunteers | Commercial Dead Sea salt mouthwash (Oral Essentials brand) | Active control (chlorhexidine) and negative control (no rinse) | Standard periodontal indices (plaque, gingivitis, bleeding) | Dead Sea and chlorhexidine rinses equally reduced periodontal inflammation vs. no rinse; no significant difference between active treatments |

| Calvo-Guirado et al. [23] | Natural seawater (moderate salinity) | Crossover design RCT | 93 dental students (19–42 years) | Marine-derived oral rinse (SEA 4 Encias brand) | Reference standard (0.2% chlorhexidine) and neutral control (saline) | Periodontal clinical parameters over 4-week trial | Marine rinse reduced plaque and gingival inflammation more than chlorhexidine and saline controls. |

| Ajdaharian et al. [24] | Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | Crossover enamel study | 10 participants providing 300 tooth samples | Experimental sensitivity rinse with Dead Sea components and plant extracts | Commercial fluoride rinse (Sensodyne) and no-rinse control | Enamel surface microhardness recovery after demineralization | Dead Sea formulation showed no advantage; enamel remineralization was comparable across groups. |

| Matceyevsky et al. [25] | Hypersaline Dead Sea minerals | Prospective cohort study | 54 cancer patients receiving head/neck radiotherapy | Prophylactic Dead Sea mineral products (oral rinse + topical cream) | Conventional supportive care | Radiation-induced oral and skin mucositis severity grading | Dead Sea mineral therapy reduced severe mucositis incidence and prevented treatment interruptions vs. standard care. |

| THERMAL WATER STUDIES | |||||||

| Silva et al. [26] | Thermal sulfur water | Observational, longitudinal, comparative study | 90 thermalists randomly allocated to groups | Thermal sulfuric natural mineral water of Amarante Thermal baths via gargles and oral showers for 14 days | Saline solution | Plaque index, gingival bleeding index, periodontal probing depth, oral mucosa disease symptoms | Greater pain reduction in TW_TA vs. saline (35.5% vs. 28.9%); OMD symptoms improved in both groups. |

| Alpöz et al. [27] | Thermal water (Castéra-Verduzan, France) | Single-blind crossover study | 20 xerostomia patients (17 women, 3 men; age 43–75 years, mean 51.5) | Buccotherm® spray 6 times daily for 14 days | Placebo (diluted tea solution with similar appearance) | Subjective xerostomia symptoms via VAS (10 items including dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, speech) | No significant difference in overall xerostomia relief vs. placebo; placebo showed lower VAS scores for mastication, swallowing, and speech (p ≤ 0.006). |

| Skrinjar et al. [28] | Thermal water (Castéra-Verduzan, France) | Open-label randomized controlled trial | 60 drug-induced hyposalivation patients (45 women, 15 men; age 45–73 years, mean 64) | Buccotherm® spray (n = 30) vs. Xeros® mouthwash (n = 15) vs. marshmallow root (n = 15); 4 times daily for 2 weeks | Three-arm comparison | Quality of life (OHIP-14), dry mouth intensity (VAS) | Buccotherm® had the greatest QoL effect size (0.52); VAS scores improved similarly across treatments (p < 0.05). |

| Toumassian et al. [29] | Thermal water (Castéra-Verduzan, France) | Prospective comparative study | 80 post-COVID syndrome patients (dental students; mean age 21.5 years) | Group I (n = 46): Buccotherm® toothpaste + mouthwash; Group II (n = 34): toothpaste + mouthwash + spray 3x/day; 3-month duration | Between-group comparison (no placebo) | Salivation rate, viscosity, pH, mineralizing potential, calcium and magnesium concentration | Mineralizing potential increased in both groups (Group I: 1.31→2.27; Group II: 1.28→2.87, p < 0.05); Group II showed greater improvements in salivation rate and mineral concentration. |

| Novozhilova et al. [30] | Thermal water (Castéra-Verduzan, France) | Double-blind parallel-group RCT | 82 patients aged 20–25 years with gingivitis and dentin hypersensitivity | Toothpaste containing 46% Castéra-Verduzan thermal water (pH 8.8): Group TW (fluoride-free, n = 41) vs. Group TWF (with 1450 ppm NaF, n = 41); twice daily for 4 weeks | Between-group comparison | Modified Gingival Index, Bleeding Index, VAS and Schiff Scale for dentin hypersensitivity, Rustogi Modified Navy Plaque Index, salivary pH | Both groups showed improved gingival condition (MGI effect sizes: TW 0.99, TWF 1.71) and bleeding (BI: TW 3.17, TWF 2.64); dentin hypersensitivity decreased more in the TWF group (VAS effect size 3.28), while plaque index improved in both groups. |

| SIMPLE SALINE SOLUTION STUDIES | |||||||

| Collins et al. [31] | Simple saline solution (artificial) | Randomized prospective double-blind study | 37 chronic periodontitis patients | Saltwater mouth rinse following open flap debridement | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse | Gingival Index, post-operative pain, mouth rinse satisfaction, matrix metalloproteinase activity | GI decreased from baseline to weeks 1 and 12 in both groups, with no significant between-group differences; saltwater was as effective as chlorhexidine. |

| Aravinth et al. [32] | Simple saline solution (artificial) | School-based randomized controlled trial | School children | Salt water rinse | Chlorhexidine mouth rinse | Dental plaque and oral microbial count | Saltwater rinse was effective as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control, with antimicrobial effects comparable to chlorhexidine |

| Kamdem et al. [33] | Simple saline solutions (artificial) | Cross-over clinical trial | 10 participants (240 saliva samples) | Homemade saline solutions at different concentrations (2%, 5.8%, 23%) | 0.1% chlorhexidine | Oral flora reduction and duration of effect | Dose-dependent antibacterial effect: 3 h (2%), 5 h (5.8%, comparable to chlorhexidine), and 7 h (23%, poorly tolerated). |

| SEA SALT FORMULATION STUDIES | |||||||

| Hoover et al. [34] | Sea salt formulation | Pilot study | 30 dental students aged 20–26 years | Sea salt, xylitol, and lysozyme mouth rinse for 30 days | Standard oral hygiene only | Turesky plaque index, gingival bleeding on probing | Overall plaque and gingivitis reduction did not differ between groups. |

| Ballini et al. [35] | Sea salt formulation | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study | 20 healthy adolescents | Combined mouth rinse with sea salt, xylitol, lysozyme, and menthol (H2Ocean) | Placebo rinse (mint-flavored water) | Plaque index, S. mutans levels | Significant reduction of S. mutans levels vs. placebo |

| Intervention Category | Studies (n) | Participants (Total n) | Percentage Countries | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypersaline Dead Sea derivatives | 7 | 154 | 41% | Israel, USA |

| Thermal/mineral waters | 5 | 332 | 35% | France, Portugal, Turkey, Croatia, Russia |

| Marine-derived solutions | 1 | 93 | 6% | Spain |

| Simple saline solutions | 3 | 47 + NR | 18% | USA, Cameroon, India |

| Study Design | Selection Bias | Performance/Observer Bias | Attrition Bias | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-blind randomized controlled trials | Low | Low | Low-Moderate | Randomization and blinding reduce bias; small samples in some studies |

| Crossover randomized trials | Low-Moderate | Low-Moderate | Low | Potential carryover effects if washout is insufficient |

| Controlled clinical trials (non-randomized/three-arm) | Moderate | Moderate | Variable | Allocation not fully random; possible baseline differences |

| Open-label randomized trials | Low-Moderate | Moderate-High | Variable | Lack of blinding may influence subjective outcomes |

| Observational and cohort studies | Moderate-High | Moderate | Variable | Convenience sampling and confounding are possible |

| Laboratory efficacy studies | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Non-clinical outcomes; limited direct clinical applicability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ferrara, E.; Scaramuzzino, M.; Rapone, B.; Murmura, G.; Sinjari, B. From Thermal Springs to Saline Solutions: A Scoping Review of Salt-Based Oral Healthcare Interventions. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010032

Ferrara E, Scaramuzzino M, Rapone B, Murmura G, Sinjari B. From Thermal Springs to Saline Solutions: A Scoping Review of Salt-Based Oral Healthcare Interventions. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrara, Elisabetta, Manela Scaramuzzino, Biagio Rapone, Giovanna Murmura, and Bruna Sinjari. 2026. "From Thermal Springs to Saline Solutions: A Scoping Review of Salt-Based Oral Healthcare Interventions" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010032

APA StyleFerrara, E., Scaramuzzino, M., Rapone, B., Murmura, G., & Sinjari, B. (2026). From Thermal Springs to Saline Solutions: A Scoping Review of Salt-Based Oral Healthcare Interventions. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010032