CarieCheck: An mHealth App for Caries-Risk Self-Assessment—User-Perceived Usability and Quality in a Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

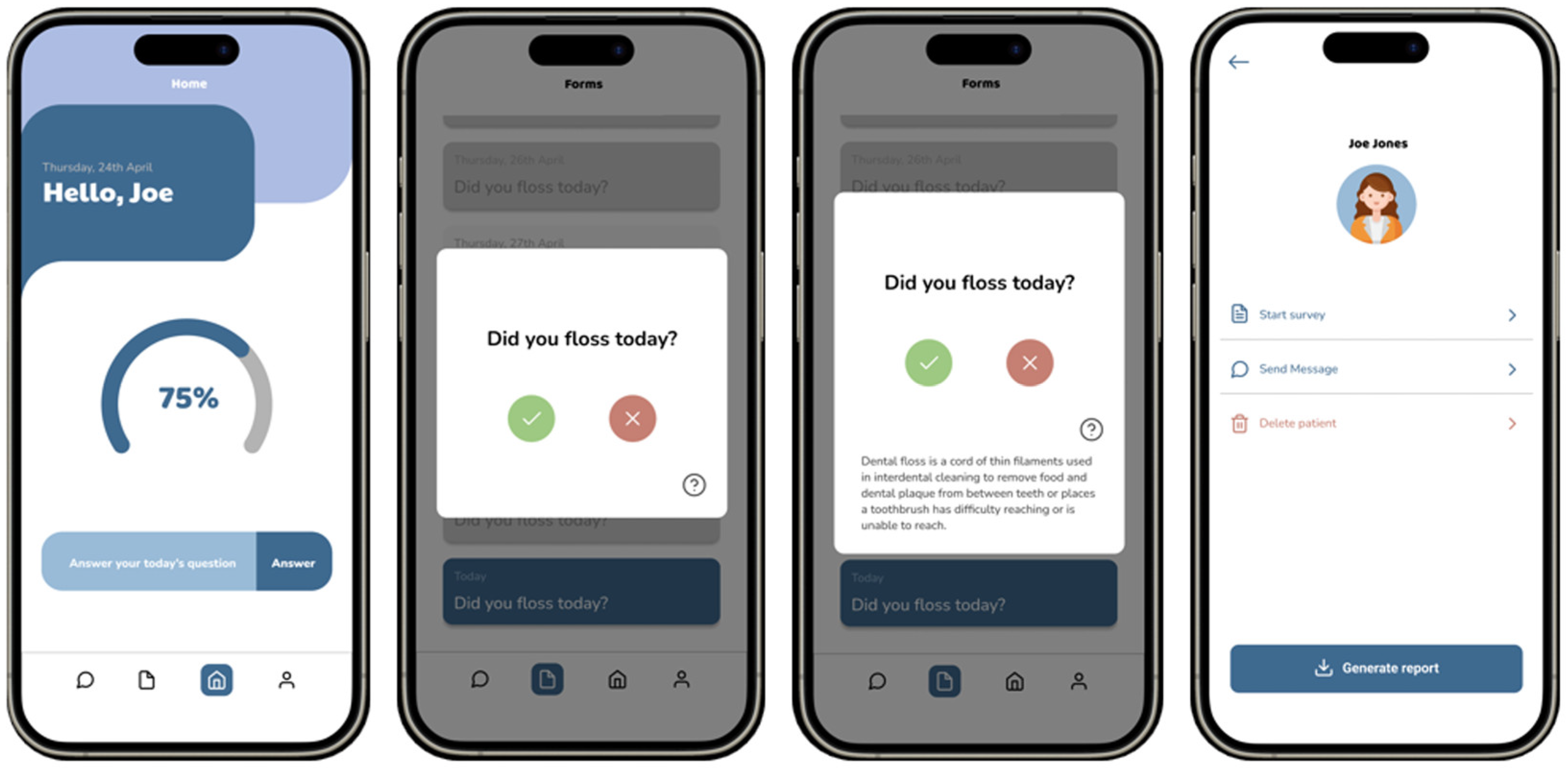

2.2. CarieCheck App

2.3. uMARS-PT Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Inclusion and Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of uMARS-PT Domains

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDPT | General Data Protection Regulation |

| MARS | Mobile App Rating Scale |

| uMARS-PT | User Mobile App Rating Scale—Version PT |

| N/A | Non-applicable |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Fontana, M.; Gonzalez-Cabezas, C. Evidence-Based Dentistry Caries Risk Assessment and Disease Management. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiulskiene, V.; Campus, G.; Carvalho, J.C.; Dige, I.; Ekstrand, K.R.; Jablonski-Momeni, A.; Maltz, M.; Manton, D.J.; Martignon, S.; Martinez-Mier, E.A.; et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujoel, P.P.; Hujoel, M.L.A.; Kotsakis, G.A. Personal oral hygiene and dental caries: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.; Cachinho, R.; Dionísio, T.; Nobre, M.; Júdice, A.; Simões, C.; Mendes, J.J. Oral Health and Dietary Habits Before and After COVID-19 Restrictions in a Portuguese Adult Population: An Observational Study. Life 2025, 15, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, B.; Engida, F.; Hanlon, C.; Prince, M.J.; Gallagher, J.E. Dental caries experience and associated factors in adults: A cross-sectional community survey within Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, J.E.; Sharma, P.; Stenhouse, L.; Green, D.; Laverty, D.; Dietrich, T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis—A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, S94–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak-Szymanik, A.; Wdowiak, A.; Szymanik, P.; Grocholewicz, K. Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease-Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghayo, H.A.; Palanyandi, C.E.; Ramphoma, K.J.; Maart, R. Oral health community engagement programs for rural communities: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsaras, G.; Gomez, J.; Hogan, R.; Ryan, M. Evaluation of a digital oral health intervention (Know Your OQ™) to enhance knowledge, attitudes and practices related to oral health. BDJ Open 2023, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mohanty, V.; Balappanavar, A.Y.; Chahar, P.; Rijhwani, K. Role of Digital Media in Promoting Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e28893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; International Telecommunication Union. Mobile Technologies for Oral Health: An Implementation Guide, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ed.; World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Istepanian, R.S.H. Mobile Health (m-Health) in Retrospect: The Known Unknowns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, J.Y.; Jo, S.R.; Cho, K.S.; Park, J.E.; Cho, J.W.; Jang, J.H. Effect of Oral Health Education Using a Mobile App (OHEMA) on the Oral Health and Swallowing-Related Quality of Life in Community-Based Integrated Care of the Elderly: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, E. The Relation Between eHealth Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väyrynen, E.; Hakola, S.; Keski-Salmi, A.; Jämsä, H.; Vainionpää, R.; Karki, S. The Use of Patient-Oriented Mobile Phone Apps in Oral Health: Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e46143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Santo, K.; Wong, G.; Sohn, W.; Spallek, H.; Chow, C.; Irving, M. Mobile Apps for Dental Caries Prevention: Systematic Search and Quality Evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.E.; Davenport, T.A.; Wong, T.; Moon, H.-W.; Hickie, I.B.; LaMonica, H.M. Evaluating the quality and safety of health-related apps and e-tools: Adapting the Mobile App Rating Scale and developing a quality assurance protocol. Internet Interv. 2021, 24, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralha, S.R.; Bittencourt, O.N.d.S. Portuguese Translation and validation of the user rating scale for mobile applications in the health area (uMARS). Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e8912642056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, J.A.; Yu, X.; Stewart, A.L.; Hays, R.D. Guidelines for Designing and Evaluating Feasibility Pilot Studies. Med. Care 2022, 60, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunselman, A. A Brief Overview of Pilot Studies and Their Sample Size Justification. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 121, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennou, A.; Lecomte, T.; Potvin, S.; Riopel, G.; Vézina, C.; Villeneuve, M.; Abdel-Baki, A.; Khazaal, Y. A Mobile Health App (ChillTime) Promoting Emotion Regulation in Dual Disorders: Acceptability and Feasibility Pilot Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e37293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Wilson, H. Development and Validation of the User Version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Zelenko, O.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Mani, M. Mobile App Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of Health Mobile Apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst, Y.; Philippi, P.; Sander, L.B.; Schultchen, D.; Paganini, S.; Bardus, M.; Santo, K.; Knitza, J.; Machado, G.C.; Schoeppe, S.; et al. Validation of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, I.F.F.; Silva, L.S. Evaluation of mobile applications related to the nursing process. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2024, 33, e202300323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K.J.; Abdul Manaf, Z.; Fitri Mat Ludin, A.; Razalli, N.H.; Mohd Mokhtar, N.; Md Ali, S.H. Mobile Apps for Common Noncommunicable Disease Management: Systematic Search in App Stores and Evaluation Using the Mobile App Rating Scale. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e49055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, É.M.A.d.; Oliveira, S.C.d.; Alves, D.S. Quality assessment of mobile applications on postpartum hemorrhage management. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2023, 57, e202320263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lee, J. The Influence of UI Design Attributes and Users’ Uncertainty Avoidance on Stickiness of the Young Elderly Toward mHealth Applications. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrig, S.A.C.; Ueffing, D.; Opwis, K.; Brühlmann, F. Smartphone app aesthetics influence users’ experience and performance. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1113842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.Y.; McGrath, C.; Yiu, C.K.Y.; Lee, G.H.M. Apps for Promoting Children’s Oral Health: Systematic Search in App Stores and Quality Evaluation. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2022, 5, e28238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | n | % | Gender (n/%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| Students | 23 | 76.7 | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) |

| Professors/Collaborators | 2 | 6.7 | 0 | 2 |

| Dental interns | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 1 |

| Volunteer Dentist in Training | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 1 |

| Administrative Staff | 3 | 10.0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 30 | 100 | 18 (60) | 12 (40) |

| Item | Engagement Domain | n | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interest: Is the app interesting to use? Does it present information in an engaging way compared with similar apps? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.9 | 1.094 |

| 2 | Entertainment: Is the app fun or enjoyable to use? Does it include features that make it more entertaining than similar apps? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.59 | 0.983 |

| 3 | Customization: Does the app allow users to personalize settings and preferences (e.g., sound, content, notifications)? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.03 | 1.033 |

| 4 | Interactivity: Does the app allow user input, provide feedback, or include prompts (reminders, sharing options, notifications, etc.)? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.60 | 0.814 |

| 5 | Target Group: Is the app’s content (visuals, language, design) appropriate for the intended target group? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.43 | 0.679 |

| Functionality Domain | ||||||

| 6 | Performance: How accurately and quickly do the app’s features (functions) and components (buttons/menus) operate? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.57 | 0.626 |

| 7 | Ease of Use: How easy is it to learn how to use the app? How clear are the menu tabs, icons, and instructions? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.67 | 0.547 |

| 8 | Navigation: Is movement between screens logical and consistent? Does the app include all necessary links between sections? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 4.27 | 0.868 |

| 9 | Gestural Design: Do touch, tap, pinch, and scroll gestures make sense? Are they consistent across components and screens? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.53 | 0.626 |

| Aesthetics Domain | ||||||

| 10 | Layout: Are the arrangement and size of buttons, icons, menus, and on-screen content appropriate? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.57 | 0.626 |

| 11 | Graphics: What is the quality and resolution of the graphical elements used for buttons, icons, menus, and content? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.57 | 0.690 |

| 12 | Visual Appeal: How visually appealing is the app overall? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.20 | 0.664 |

| Information Quality Domain | ||||||

| 13 | Information Quality: Is the app content correct, well written, and relevant to the app’s purpose/topic? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.55 | 0.572 |

| 14 | Quantity of Information: Is the information provided complete and objective? | 20 | 1 | 5 | 4.10 | 1.012 |

| 15 | Visual Information: Are visual explanations of concepts (tables, graphs, images, videos, etc.) clear, logical, and accurate? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.54 | 0.637 |

| 16 | Credibility: Does the information appear to come from a reliable and trustworthy source? | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.50 | 0.638 |

| 17 | Recommendation: Would you recommend this app to people who could benefit from using it? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.90 | 1.094 |

| 18 | Intended Use: How often do you think you would use this app over the next 12 months if it were relevant to you? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.70 | 1.179 |

| Subjective Quality Domain | ||||||

| 19 | Would you pay for this app? | 30 | 1 | 5 | 2.30 | 1.055 |

| 20 | What is your overall star rating for the app? | 30 | 2 | 5 | 3.80 | 0.847 |

| Perceived Impact Domain | ||||||

| 21 | Awareness: This app increased my awareness of the importance of addressing my health-related habits and behaviors. | 30 | 2 | 5 | 4.03 | 0.718 |

| 22 | Knowledge: This app increased my knowledge or understanding regarding my health-related habits and behaviours. | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.73 | 0.944 |

| 23 | Attitudes: This app changed my attitudes in a way that improved my health-related habits and behaviours. | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.67 | 0.922 |

| 24 | Intention to Change: This app increased my intention or motivation to address my health-related habits and behaviours. | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.90 | 0.885 |

| 25 | Help Seeking: This app would encourage me to seek additional help to deal with my health-related habits and behaviors (if needed). | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.93 | 0.868 |

| 26 | Behaviour Change: Using this app will increase or decrease my health-related habits and behaviours. | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.83 | 0.950 |

| Domain | Items | Mean (Domain) | Qualitative Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | 1–5 | 3.71 | Acceptable/Moderate Quality |

| Functionality | 6–9 | 4.51 | Excellent Quality |

| Aesthetics | 10–12 | 4.45 | Excellent Quality |

| Information Quality | 13–18 | 4.22 | Excellent Quality |

| Subjective Quality | 19–20 | 3.05 | Acceptable/Moderate Quality |

| Perceived Impact | 21–26 | 3.85 | Acceptable/Moderate Quality |

| Overall MARS Score | 1–18 | 4.22 | Excellent Quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guerreiro, E.; Souza, G.; Mendes, J.J.; Manso, A.C.; Botelho, J. CarieCheck: An mHealth App for Caries-Risk Self-Assessment—User-Perceived Usability and Quality in a Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010031

Guerreiro E, Souza G, Mendes JJ, Manso AC, Botelho J. CarieCheck: An mHealth App for Caries-Risk Self-Assessment—User-Perceived Usability and Quality in a Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerreiro, Eduardo, Guilherme Souza, José João Mendes, Ana Cristina Manso, and João Botelho. 2026. "CarieCheck: An mHealth App for Caries-Risk Self-Assessment—User-Perceived Usability and Quality in a Pilot Study" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010031

APA StyleGuerreiro, E., Souza, G., Mendes, J. J., Manso, A. C., & Botelho, J. (2026). CarieCheck: An mHealth App for Caries-Risk Self-Assessment—User-Perceived Usability and Quality in a Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010031