Laser Therapy for Vascular Malformations of the Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

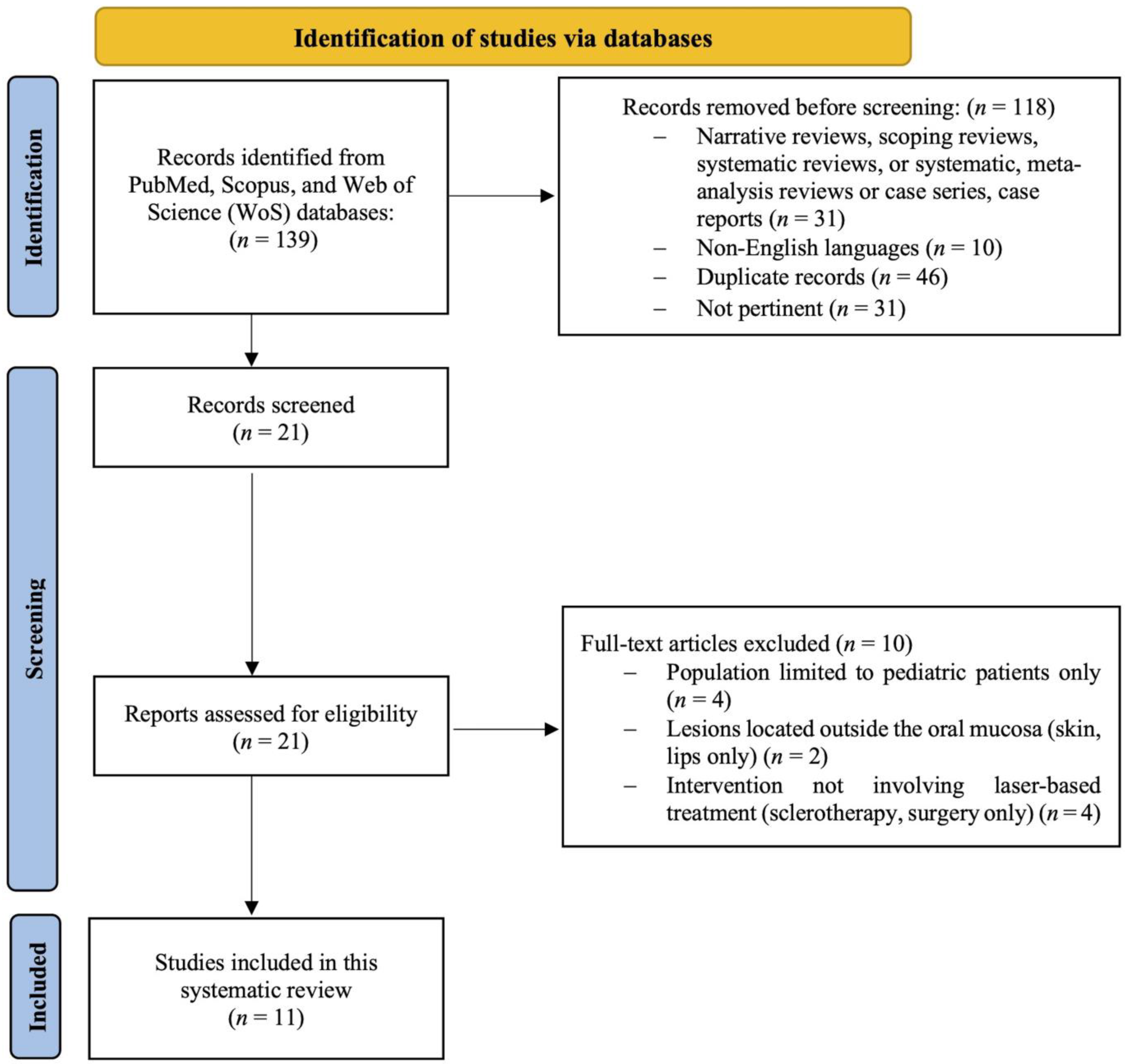

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol and Registration

2.2. Focused Questions

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias

3.2. Results of Syntheses

3.2.1. Nd:YAG Laser for Deep Lesions

3.2.2. Diode Laser for Low-Flow Malformations

3.2.3. KTP Laser for Small VMs

3.2.4. Er,Cr:YSGG and CO2 Lasers for Scar Reduction

3.2.5. Laser Forced Dehydration (LFD) for Low-Flow Lesions

3.2.6. Descriptive Data from Comparative Studies: Laser vs. Other Treatments

4. Discussion

4.1. Nd:YAG Laser

4.2. Diode Laser

4.3. Er,Cr:YSGG Laser

4.4. Carbon Dioxide Laser (CO2)

4.5. Potassium Titanyl Phosphate Laser (KTP)

4.6. Laser Versus Cold Scalpel and Sclerotherapy

4.7. Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CW | Continuous wave |

| Er,Cr:YSGG | Erbium, Chromium: Yttrium-Scandium-Gallium-Garnet. |

| FDIP | Forced dehydration with induced photocoagulation |

| ILP | Intralesional photocoagulation |

| KTP | Potassium titanyl phosphate |

| LT | Laser therapy |

| Nd:YAG | Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet. |

| NHLBI | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute |

| OVA | Oral vascular anomaly |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews |

| RR | Relative risk |

| RoB | Risk of bias |

| ROBINS-I V2 | Risk Of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—of Interventions, Version 2 |

| VLs | Venous lakes |

| VeMs | Vascular venous malformations |

| VMs | Vascular malformations |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Gobbo, M.; Guarda-Nardini, L. Laser Forced Dehydration of Benign Vascular Lesions of the Oral Cavity: A Valid Alternative to Surgical Techniques. Medicina 2024, 60, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Suzuki, H.; Takeuchi, J.; Komori, T. Effectiveness of Photocoagulation Using an Nd:YAG Laser for the Treatment of Vascular Malformations in the Oral Region. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadavid, A.M.H.; de Campos, W.G.; Aranha, A.C.C.; Lemos-Junior, C.A. Efficacy of Photocoagulation of Vascular Malformations in the Oral Mucosa Using Nd: YAG laser. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2018, 29, e614–e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, C.; Sacchetto, L.; Zanette, G.; Sivolella, S. Diode Laser to Treat Small Oral Vascular Malformations: Prospective Case Series Study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2018, 50, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nammour, S.; El Mobadder, M.; Namour, M.; Namour, A.; Arnabat-Dominguez, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Vanheusden, A.; Vescovi, P. Aesthetic Treatment Outcomes of Capillary Hemangioma, Venous Lake, and Venous Malformation of the Lip Using Different Surgical Procedures and Laser Wavelengths (Nd:YAG, Er,Cr:YSGG, CO2, and Diode 980 nm). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azma, E.; Razaghi, M. Laser Treatment of Oral and Maxillofacial Hemangioma. J. Lasers Med Sci. 2018, 9, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waner, M.; O, T. Lasers and Treatment of Congenital Vascular Lesions. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2022, 51, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, R.; Mezghani, N.; Kaleem, A.; Melville, J.C. Lasers and Nonsurgical Modalities. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 36, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosraviani, F.; Ehsani, S.; Fathi, M.; Saberi-Demneh, A. Therapeutic Effect of Laser on Pediatric Oral Soft Tissue Problems: A Systematic Literature Review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 1735–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tool. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I V2: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions. 2024. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/robins-i-v2 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Tempesta, A.; Dell’olio, F.; Siciliani, R.A.; Favia, G.; Capodiferro, S.; Limongelli, L. Targeted Diode Laser Therapy for Oral and Perioral Capillary-Venous Malformation in Pediatric Patients: A Prospective Study. Children 2023, 10, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungnirandr, A.; Nuntasunti, W.; Manuskiatti, W. Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminium Garnet Laser Treatment of Pediatric Venous Malformation in the Oral Cavity. Dermatol. Surg. 2016, 42, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, E.; Yumeen, S.; Tannous, Z. Acquired port-wine stains: A report of two cases and review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 22, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Caille, A.; Gissot, V.; Giraudeau, B.; Lengelle, C.; Bourgoin, H.; Largeau, B.; Leducq, S.; Maruani, A. Topical sirolimus solution for lingual microcystic lymphatic malformations in children and adults (TOPGUN): Study protocol for a multicenter, randomized, assessor-blinded, controlled, stepped-wedge clinical trial. Trials 2022, 23, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, N.G.; Kurian, N.; Kashyap, R.R.; Kini, R.; Rao, P.K.; Thomas, A. The star-crossed curse of childhood: A case of infantile hemangioma. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2019, 37, 209–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, D.A.F.; Ito, F.A.; de Lima, H.G.; Novais, J.D.; Novais, J.B.; Dallazen, E.; Takahama, A., Jr. Sclerotherapy for Extensive Vascular Malformation in the Tongue. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, e796–e799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.-W.; Ohe, J.-Y.; Jung, J. Usefulness of a Low-Dose Sclerosing Agent for the Treatment of Vascular Lesions in the Tongue. Cureus 2023, 15, e45323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitra, G.; Kayalvizhi, E.B.; Sivasankari, T.; Vishwanath, R. A new venture with sclerotherapy in an oral vascular lesion. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2014, 6, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, P.E.T.; Sánchez-Carpintero, I.; López-Gutiérrez, J.C. Preventive treatment with oral sirolimus and aspirin in a newborn with severe Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, D.C.; Carvas, M.; Adams, D.; Giannotti, M.; Gemperli, R. Successful Treatment of a Complex Vascular Malformation With Sirolimus and Surgical Resection. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2017, 39, e191–e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukawa, H.; Kono, M.; Hamada, H.; Okamoto, A.; Satomi, T.; Chikazu, D. Indications of Potassium Titanyl Phosphate Laser Therapy for Slow-Flow Vascular Malformations in Oral Region. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2017, 28, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Ohshiro, T.; Romeo, U.; Noguchi, T.; Maruoka, Y.; Gaimari, G.; Tomov, G.; Wada, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Ohshiro, T.; et al. Retrospective Study on Laser Treatment of Oral Vascular Lesions Using the “Leopard Technique”: The Multiple Spot Irradiation Technique with a Single-Pulsed Wave. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2018, 36, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limongelli, L.; Tempesta, A.; De Caro, A.; Maiorano, E.; Angelelli, G.; Capodiferro, S.; Favia, G. Diode Laser Photocoagulation of Intraoral and Perioral Venous Malformations After Tridimensional Staging by High Definition Ultrasonography. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivhare, P.; Haidry, N.; Sah, N.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.; Singh, A.; Penumatcha, M.R.; Subramanyam, S.; Caggiati, A. Comparative Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety of the Diode Laser (980 nm) and Sclerotherapy in the Treatment of Oral Vascular Malformations. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2022, 2022, 2785859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhoshi, M.; Qafmolla, A.; Gutknecht, N.; D’Amico, C.; Fiorillo, L. 980 nm Diode Laser for Treatment of Vascular Lesions in Oral District: A 5 Years Follow-Up Trial. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimlich, F.V.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Kato, C.d.N.A.d.O.; Silva, L.V.d.O.; Souza, L.N.; Ferreira, M.V.L.; Pinheiro, J.d.J.V.; Silva, T.A.; Abreu, L.G.; Mesquita, R.A. Experience with 808-nm diode laser in the treatment of 47 cases of oral vascular anomalies. Braz. Oral Res. 2024, 38, e025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Rehman, F.; Chaturvedy, V. Soft Tissue Applications of Er,Cr:YSGG Laser in Pediatric Dentistry. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2017, 10, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnaashari, M.; Roudsari, M.B.; Shirmardi, M.S. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Laser in Minor Oral Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Lasers Med Sci. 2023, 14, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Study design: including retrospective and prospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and randomized controlled trials | Abstracts of articles published in non-English languages |

| 10-year time frame (from 2014 to 2024) | Duplicate studies |

| Human participants diagnosed with VMs of the oral cavity, including adults and mixed-age populations, but not studies exclusively focused on pediatric patients | Book chapters, narrative, systematic, meta-analysis reviews, case series, or case reports |

| Interventions: Laser therapy for the excision of vascular malformation | Studies focused exclusively on pediatric populations were excluded to ensure homogeneity in lesion characteristics and treatment response |

| Outcome: Laser effectiveness and safety in the treatment of vascular lesions | - |

| Reference First Author et al. Year | A A1/A2/A3 | B B1/B2 | C | D1 (VA) | D2 | D3 | D4 (VA) | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall Risk-of-Bias Judgement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobbo et al., 2024 [1] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Asai et al., 2014 [2] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Cadavid et al., 2018 [3] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bacci et al., 2018 [4] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Nammour et al., 2020 [5] | PY | NA | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Abukawa et al., 2017 [24] | PY | NA | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Miyazaki et al., 2018 [25] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Limongelli et al., 2019 [26] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Shivhare et al., 2022 [27] | PY | NA | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bardhoshi et al., 2022 [28] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Heimlich et al., 2024 [29] | PN | PN | N | N (D1—VA) | / | To assess the intention-to-treat effect (the effect of assignment to an intervention strategy or comparator strategy) (D4—VA). |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| References (Authors, Year, and Publication Country) | N° of Patients (N° Woman) | Mean Age ± SD and/or Range (Years) | Lesion Size (n° of Lesions) | Treated Lesion Number | Anatomical Site (n° of Lesions) | N° of Lesions with Complete Healing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobbo et al., 2024 Italy [1] | 30 (16) | 67, range 41–86 | 2–25 mm | 30 | Tongue (4), gingiva (2), lip (19), palate (1), cheek (4) | N.R. |

| Asai et al., 2014 Japan [2] | 67 (44) | 50.0, range 7–89 | Group 1 <15 mm (56); Group 2 >15 mm (13) | 69 | Lip (33), tongue (25), buccal mucosa (6), gingiva (2), mouth floor (2), soft palate (1) | 62 of 69 |

| Cadavid et al., 2018 Brazil [3] | 93 (57) | 63.3, range 8–85 | Most lesions were <3 cm | 104 | Inferior lip (44), superior lip (15), tongue (13), palate (6), jugal mucosa (22), gum (3), retromolar trigone (1) | N.R. |

| Bacci et al., 2018 Italy [4] | 59 (28) | 53, range 30–73 | N.R. | 59 | Lip (18), tongue (15), alveolar mucosa (16), palate (7), gum (3) | 48 of 59 |

| Nammour et al., 2020 Belgium [5] | 143 (81) | 48, range 43–74 | 3–15 mm | 143 | N.R. | N.R. |

| Abukawa et al., 2017 Japan [24] | 26 (17) | 55.7 | <9 mm (13), 10–19 mm (19), 19–29 mm (4), >30 mm (2) | 38 | Tongue (13), lip (11), buccal mucosa (6), gingiva (3), masseter (3), floor of the mouth (1), palate (1) | N.R |

| Miyazaki et al., 2018 Japan [25] | 46 | N.R. | N.R. | 47 | Tongue (17), buccal mucosa (30), gingiva (0) | 36 of 47 |

| Limongelli et al., 2019 Italy [26] | 112 (52) | 42, N.R. | Group A (52) <1 cm; Group B1 (28) 1–3 cm and <5 mm depth; Group B2 (16) 1–3 cm and >5 mm depth; Group C1 (42) >3 cm and <5 mm depth; Group C2 (12) >3 cm and >5 mm depth. | 158 | Lower lip (32), upper lip (9), tongue (41), fornix (5), palate (12), cheek (46), perioral skin (13) | 100‰ (Group A); 93% (Group B1); 90% (Group B2); 88% (Group C1); 84% (Group C2) |

| Shivhare et al., 2022 India [27] | 40 (16) | N.R. | <1 cm (15), 1–2 cm (10), 2–3 cm (8), >3 cm (7) | 40 | Tongue (18), buccal mucosa (11), lower labial mucosa (6), upper labial mucosa (3), palate (2) | N.R. |

| Bardhoshi et al., 2022 Albania [28] | 60 (28) | N.R., range 10–80 | N.R. | 60 | N.R. | N.R. |

| Heimlich et al., 2024 Brazil [29] | 47 (17) | 57.4 (±14.9), range 7–81 | 2–20 mm | 47 | Lower lip (22), upper lip (13), tongue (7), buccal mucosa (4), alveolar ridge (1) | N.R. |

| Authors and Publication Year | Study Type and Objectives | Methods | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobbo et al., 2024 Italy [1] | Prospective observational study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of laser forced dehydration (LFD) on low-flow vascular lesions. | Lesions were treated using LFD and followed up at 3 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. In cases of incomplete healing at 3 weeks, an additional session was performed. Outcomes assessed included pain (NRS 0–10), analgesic requirement, bleeding, and scar formation. | Inclusion: pigmented, soft, non-pulsatile lesions with positive diascopy, accessible to laser. Exclusion: age < 18, pregnancy or breastfeeding, refusal to participate in 1-year follow-up. | Complete lesion regression was observed in all cases. One patient required a second session. No pain was reported (NRS = 0), and no analgesics were used. Minor bleeding occurred in one patient and a small scar in another. No recurrences were reported. | LFD proved to be effective and painless, often without anesthesia. Glass slides can minimize bleeding. Anatomical challenges may require multiple low-power sessions. |

| Asai et al., 2014 Japan [2] | Retrospective observational study assessing the clinical effectiveness of Nd:YAG laser photocoagulation for oral VMs. | Between 2004 and 2011, 67 patients were treated using 8–15 W Nd:YAG laser under local anesthesia. | Inclusion/Exclusion: N.R. | Deeper lesions required multiple sessions. External laser application alone yielded satisfactory results without clinical complications. | Nd:YAG laser was found effective and minimally invasive, with no significant adverse events. |

| Cadavid et al., 2018 Brazil [3] | Retrospective observational study evaluating the efficacy of Nd:YAG laser photocoagulation in treating oral and perioral VMs. | From 2006 to 2013, 93 patients were treated using 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser (400 µm fiber) under local anesthesia. | Inclusion/Exclusion: N.R. | No complications were recorded. Deep lesions required multiple treatment sessions. | Nd:YAG laser was effective and minimally invasive, with excellent aesthetic outcomes. Further studies are needed to confirm superiority over alternative methods. |

| Bacci et al., 2018 Italy [4] | Prospective observational study evaluating transmucosal diode laser treatment in patients with VeMs or VLs. | Fifty-nine patients with low-flow lesions were treated with 830 nm diode laser (1.6 W) and followed up at 7 days, 30 days, and 1 year. Pain was recorded daily for the first 7 days. | Exclusion: Pulsatile lesions, syndromic conditions, prior immunosuppressive therapy, extra-oral extension, or vascular tumors. | At 30 days, 52 patients showed excellent/good lesion reduction. Six required a second treatment. At 1 year, 48 achieved complete resolution; five experienced recurrence. | Diode laser is effective with reduced operative time and fewer complications. Lesions > 10 mm may require multiple sessions. |

| Nammour et al., 2020 Belgium [5] | Retrospective observational study evaluating scar quality, recurrence, and patient satisfaction across various laser treatments. | 143 patients with congenital hemangiomas or VMs were treated with Nd:YAG, diode (980 nm), Er,Cr:YSGG, or CO2 lasers. Follow-up was 12 months. | Inclusion: Patients with unaesthetic VL. Exclusion: Chronic diseases, diabetes, immunosuppression, concurrent tumors. | All lasers improved scar quality at 12 months. Er,Cr:YSGG and CO2 lasers had better results at 2 weeks. The highest level of patient satisfaction was reported with Er,Cr:YSGG. | Multiple laser types are effective. Er,Cr:YSGG yielded the best early aesthetic outcomes. |

| Abukawa et al., 2017 Japan [24] | Prospective observational study aimed to determine the resolution rate of slow-flow VMs and identify risk and prognostic factors linked to successful outcomes with potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser treatment. | Twenty-six patients underwent intralesional laser photocoagulation under local anesthesia, with a consistent KTP laser power of 2 watts. Outcomes were measured through clinical assessments and lesion size reduction observed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). | Inclusion Criteria: Patients with diagnosed venous or capillary malformations. Exclusion Criteria: Patients with hemangiomas, arteriovenous malformations, lymphatic malformations, those on anticoagulants, or those who did not undergo MRI. | Lesions treated with less than 400 joules responded effectively. However, buccal mucosal lesions and those treated with higher energy levels had a higher rate of complications like necrosis. | KTP laser therapy effectively treated slow-flow VMs smaller than 30 mm with minimal side effects. |

| Miyazaki et al., 2018 Japan [25] | Retrospective observational study assessing efficacy of Nd:YAG laser with multiple spot single-pulse technique. | 46 patients with 47 lesions treated with 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser; 24 lesions required combined intralesional therapy. | Inclusion/Exclusion: N.R. | Satisfactory outcomes in all cases; no serious adverse events like ulceration, bleeding, or scarring. | Nd:YAG laser is a safe, less invasive option for managing oral vascular lesions. |

| Limongelli et al., 2019 Italy [26] | Retrospective observational study to determine optimal diode laser settings for head and neck VMs. | 158 lesions categorized by size and depth, treated with 800 ± 10 nm diode laser using transmucosal, cutaneous, or intralesional photocoagulation. | Inclusion/Exclusion: N.R. | All lesions fully healed at 1 year. Larger/deeper lesions required up to 10 sessions. Mild-moderate postoperative pain occurred in 5–7% of cases. | Optimized laser parameters improved tolerance, healing time, and reduced complications. |

| Shivhare et al., 2022 India [27] | Prospective observational study comparing diode laser and sclerotherapy for oral VMs. | 40 patients randomly assigned to diode laser (980 nm) or sclerotherapy (3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate). Outcomes assessed using chi-square test. | Inclusion: Low-flow lesions confirmed by Doppler and CT angiogram. Exclusion: High-flow lesions or systemic anomalies. | Laser group had significantly fewer side effects and less pain. Recurrence was more frequent compared to sclerotherapy. | Both treatments are effective. Laser is better tolerated but may have higher recurrence. |

| Bardhoshi et al., 2022 Albania [28] | Retrospective observational study comparing diode laser and cold scalpel for VLs. | 60 patients treated between 2007–2012; 30 with 980 nm diode laser, 30 with scalpel surgery. Follow-up at 1, 6, and 12 months. | Inclusion/Exclusion: N.R. | Laser showed better outcomes in bleeding control, patient acceptance, and scar minimization. | Diode laser is effective across all age groups with superior hemostatic and aesthetic results. |

| Heimlich et al., 2024 Brazil [29] | Prospective observational study on diode laser photocoagulation (FDIP) in OVA. | 47 patients treated with 808 nm diode laser (4.5 W, pulsed mode). Follow-up assessed healing rate and recurrence. | Inclusion: Esthetic/functional concerns, superficial low-flow lesions. Exclusion: Previous treatments, systemic disease, or lack of follow-up. | Complete healing in 70.5% within 30 days. Edema occurred in 66%, and recurrence in 4.2%. | FDIP is effective and safe, often requiring only a single session with minimal adverse effects. |

| Authors and Year of Publication | Laser Type | Wavelength (nm) | Power Output (W) | Emission Mode | Sessions (Number of Lesions) | Cooling/Gel Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobbo et al., 2024 Italy [1] | Diode laser | 445 nm 970 nm | N.R. | Pulsed | N.R. | N.R. |

| Asai et al., 2014 Japan [2] | Nd:YAG laser | 1064 nm | 8–15 W | N.R. | 1 (62), 2 (5), 3 (1), 7 (1) | N.R. |

| Cadavid et al., 2018 Brazil [3] | Nd:YAG laser | 1064 nm | 3 W | Pulsed | N.R. | N.R. |

| Bacci et al., 2018 Italy [4] | Diode laser | 830 nm | 1.6 W | Continuous | 1 (46), 2 (6) | Physiological solution |

| Nammour et al., 2020 Belgium [5] | Nd:YAG, diode, Er,Cr:YSGG, CO2 | 1064 nm, 980 nm, 2790 nm, 10,600 nm | 2 W, 4 W, 0.25 W, 1 W | Pulsed: 320 μs Continuous Pulsed: 60 μs Continuous | N.R. (47) N.R. (32) N.R. (12) N.R. (52) | N.R. |

| Abukawa et al., 2017 Japan [24] | KTP laser | N.R. | 2 W | N.R. | Average 1.1 (N.R.) | N.R. |

| Miyazaki et al., 2018 Japan [25] | Nd:YAG laser | 1064 nm | 10 W | Pulsed: 20 ms | N.R. | N.R. |

| Limongelli et al., 2019 Italy [26] | Diode laser | 800 ± 10 nm | 8 W 12 W 13 W | Pulsed: 190 ms t-on and 250 ms t-off | 1(52), 2 (28), 3 (16), 5 (42), 10 (20) | Topic cryotherapy with ice packs |

| Shivhare et al., 2022 India [27] | Diode laser | 980 nm | 2–3 W | Continuous | 1 session (22), 2 session (11), 3 or >3 (7) | N.R. |

| Bardhoshi et al., 2022 Albania [28] | Diode laser | 980 nm | 3 W | Continuous | N.R. | N.R. |

| Heimlich et al., 2024 Brazil [29] | Diode laser | 800 ± 10 nm | 4.5 W | Pulsed: 25 ms | 1 session | N.R. |

| Authors and Year of Publication | Treated Lesion Number | Complete Healing | Aesthetic Outcome | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobbo et al., 2024 Italy [1] | 30 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Asai et al., 2014 Japan [2] | 69 | 62/69 | Good aesthetic outcomes | No major complications |

| Cadavid et al., 2018 Brazil [3] | 104 | N.R. | N.R. | Minimal side effects reported |

| Bacci et al., 2018 Italy [4] | 59 | 48/59 | Excellent cosmetic results | Minor discomfort |

| Nammour et al., 2020 Belgium [5] | 143 | N.R. | N.R. | No serious adverse effects |

| Abukawa et al., 2017 Japan [24] | 38 | N.R. | N.R. | No complications reported |

| Miyazaki et al., 2018 Japan [25] | 47 | 36/47 | High satisfaction rate | Mild postoperative pain |

| Limongelli et al., 2019 Italy [26] | 158 | Group A: 100%; Group B1: 93%; B2: 90%; C1: 88%; C2: 84% | Improved cosmetic appearance | No significant adverse events |

| Shivhare et al., 2022 India [27] | 40 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Bardhoshi et al., 2022 Albania [28] | 60 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Heimlich et al., 2024 Brazil [29] | 47 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellegrini, M.; Bosisio, M.; Pulicari, F.; Todea, C.D.; Spadari, F. Laser Therapy for Vascular Malformations of the Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090416

Pellegrini M, Bosisio M, Pulicari F, Todea CD, Spadari F. Laser Therapy for Vascular Malformations of the Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(9):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090416

Chicago/Turabian StylePellegrini, Matteo, Martina Bosisio, Federica Pulicari, Carmen Darinca Todea, and Francesco Spadari. 2025. "Laser Therapy for Vascular Malformations of the Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 9: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090416

APA StylePellegrini, M., Bosisio, M., Pulicari, F., Todea, C. D., & Spadari, F. (2025). Laser Therapy for Vascular Malformations of the Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal, 13(9), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090416