Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Versus Incremental Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

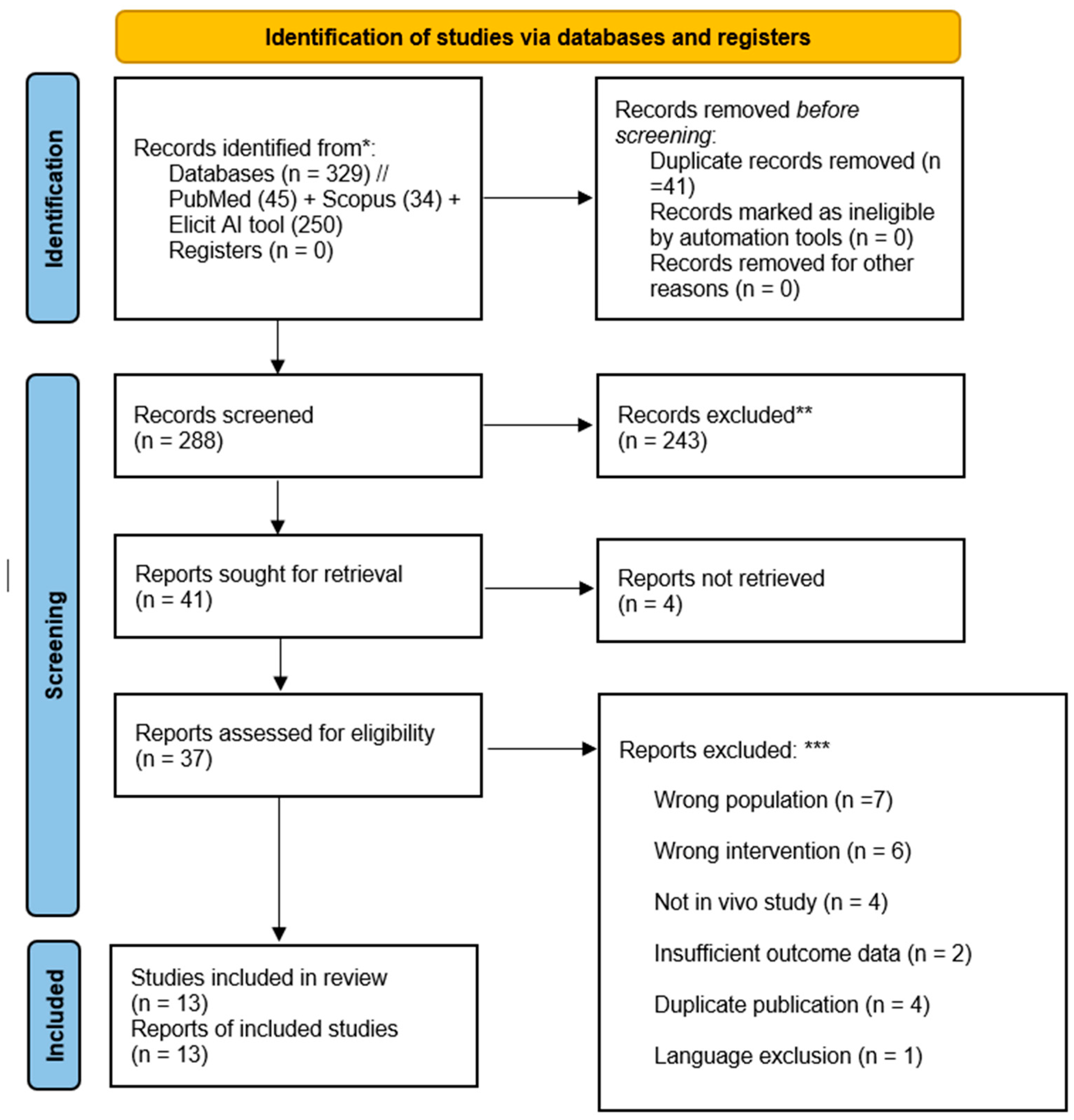

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Assessment of Reporting Bias and Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

- The remaining studies showed “some concerns” in one or more domains, most frequently in the randomization process (due to incomplete reporting on allocation procedures) and measurement of the outcome.

- One study had multiple domains with “some concerns” (randomization, outcome measurement, and selective reporting) but was not judged to have high risk in any domain [14].

| Study | Study Design | Sample Size | Follow-Up Period | Evaluation Criteria | Population Details | Intervention Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akman and Tosun, 2020 [11] | RCT, Prospective | 30 patients, 160 restorations | 12 months | Modified USPHS | Children aged 6–10, primary molars | Sonicfill, X-tra fil vs. Filtek Z550 |

| Banon et al., 2024 [12] | RCT, Split-mouth | 20 children, 96 molars | 24 months | USPHS-Ryge | Children aged 5–10, primary molars | ACTIVA BioACTIVE vs. Dyract eXtra |

| Deepika et al., 2022 [13] | RCT, Split-mouth | 50 children, 100 primary molars | 12 months | Modified USPHS | Children aged 5–9, primary molars | ACTIVA Bioactive vs. Beautifil flow Plus |

| Ehlers et al., 2019 [14] | RCT, Split-mouth | 32 children | 12 months | FDI | Children aged 4–9, primary molars | Venus Bulk Fill vs. Dyract eXtra |

| Gindri et al., 2022 [15] | RCT | 65 participants, 140 restorations | 12 months | FDI | Children aged 5.2–8.2, primary molars | Filtek Bulk Fill vs. Filtek Z350 XT |

| Cantekin and Gumus, 2014 [16] | RCT, Prospective | 20 children | 12 months | Modified Zurn and Seale | Children aged 5–7, primary molars | SDR flow vs. Aelite LS Posterior |

| Lardani et al., 2022 [17] | Split-mouth RCT | 45 children | 12 months | FDI | Children aged 5–9, primary molars | ACTIVA BioActive, SDR Bulk-fill |

| Lucchi et al., 2024 [18] | Retrospective study | 198 patients | 5 years | USPHS | Children aged 0–12, 673 restorations | Filtek Bulk-Fill Flow |

| Massa et al., 2022 [19] | RCT | 62 subjects, 144 primary molars | 18 months | FDI | Children aged 4.2–7.6, primary molars | Filtek Bulk Fill Posterior |

| Olegário et al., 2022 (1) [20] | RCT | 91 children | 12 months | Roeleveld | Children aged 3–8, primary molars | Filtek Bulk Fill |

| Olegário et al., 2022 (2) [21] | RCT | 93 children | 24 months | Roeleveld | Children aged 4–8, primary molars | Filtek Bulk Fill |

| Sarapultseva and Sarapultsev, 2019 [22] | Split-mouth RCT | 27 children | 24 months | Modified Ryge | Children aged 3–6, mandibular molars | SDR vs. Ceram-X mono |

| Öter et al. [8] | RCT, Split-mouth | 80 children | 12 months | Modified USPHS | Children aged 5.61–9.21, primary molars | Filtek Bulk-Fill vs. Filtek Z250 |

3.1. Study Characteristics and Overview

- Primary outcomes: retention, survival rate at 24 months, and marginal integrity.

- Secondary outcomes: postoperative sensitivity, aesthetic appearance, and secondary caries incidence (where reported).

3.2. Primary Clinical Outcomes

3.3. Secondary Clinical Outcomes

3.4. Procedural Outcomes

3.5. Failure Characteristics

3.6. Time-Based Success Analysis

3.7. Analysis by Cavity Classification

3.8. Other Factors

3.9. Analysis of Systematic Reviews with a Relevant Review Question

4. Discussion

- There was substantial heterogeneity in materials used (e.g., viscosity of bulk-fill), adhesive protocols, and evaluation criteria.

- Follow-up durations varied from 12 to 60 months, with relatively few studies extending beyond 2 years.

- Some studies paired bulk-fill and incremental composites with different adhesive systems, introducing potential confounding.

- Although a split-mouth design was employed in several studies, the possibility of cross-arch effects or intraoral variability may have influenced results.

- No meta-analysis was performed due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidance.

5. Conclusions

- Detailed analysis of failure modes and timing.

- Standardized documentation of composite and adhesive materials used.

- Systematic assessment of technique sensitivity across different operator skill levels.

- Transparent reporting of operator experience and training, ideally following CONSORT guidelines.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veloso, S.R.M.; Lemos, C.A.A.; de Moraes, S.L.D.; do Egito Vasconcelos, B.C.; Pellizzer, E.P.; de Melo Monteiro, G.Q. Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill and Conventional Resin Composite Restorations in Posterior Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2019, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.; Naka, O.; Mehta, S.B.; Banerji, S. The Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill versus the Incremental Layered Application of Direct Resin Composite Restorations: A Systematic Review. Evid. Based Dent. 2023, 24, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lei, H.; Liu, Y.; Xia, B. Clinical Evaluation of SonicFill Bulk Resin Technique in the Restoration of Proximal Deep Caries of Primary Molars: A Two-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Sotomayor, P.; Ortega, G.; Aguilar, J.; Ordóñez, P.; Rojas, M.; Vásquez, R. Dental Restoration Operative Time and Analysis of the Internal Gap of Conventional Resins (Incremental Technique) vs. Bulk Fill (Single-Increment Technique): In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2023, 15, e621–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganini, A.; Attin, T.; Tauböck, T.T. Margin Integrity of Bulk-Fill Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth. Materials 2020, 13, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, H.J.; Marovic, D.; Par, M.; Thieu, M.K.L.; Reseland, J.E.; Johnsen, G.F. Bulk Fill Composites Have Similar Performance to Conventional Dental Composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shazly, R.K.; El-Zayat, I.M.A.; Mohsen, M.M.A.; Labib, M.E.M. Clinical Evaluation of Self-Adhesive Bulk-Fill Composite Versus Conventional Nano-Hybrid Composite in Cervical Cavities-A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2025, 37, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oter, B.; Deniz, K.; Cehreli, S.B. Preliminary Data on Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Restorations in Primary Molars. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; AlKhalefah, A.S.; Alsaghirat, A.A.; Alburayh, R.A.; Alabdullah, N.A. Comparison between Different Bulk-Fill and Incremental Composite Materials Used for Class II Restorations in Primary and Permanent Teeth: In Vitro Assessments. Materials 2023, 16, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, H.; Tosun, G. Clinical Evaluation of Bulk-Fill Resins and Glass Ionomer Restorative Materials: A 1-Year Follow-up Randomized Clinical Trial in Children. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banon, R.; Vandenbulcke, J.; Van Acker, J.; Martens, L.; De Coster, P.; Rajasekharan, S. Two-Year Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation of ACTIVA BioACTIVE versus Compomer (Dyract® eXtra) in the Restoration of Class-2 Cavities of Primary Molars: A Non-Inferior Split-Mouth Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepika, U.; Sahoo, P.K.; Dash, J.K.; Baliarsingh, R.R.; Ray, P.; Sharma, G. Clinical Evaluation of Bioactive Resin-Modified Glass Ionomer and Giomer in Restoring Primary Molars: A Randomized, Parallel-Group, and Split-Mouth Controlled Clinical Study. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2022, 40, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, V.; Gran, K.; Callaway, A.; Azrak, B.; Ernst, C.-P. One-Year Clinical Performance of Flowable Bulk-Fill Composite vs Conventional Compomer Restorations in Primary Molars. J. Adhes. Dent. 2019, 21, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindri, L.D.; Cassol, I.P.; Fröhlich, T.T.; Rocha, R.d.O. One-Year Clinical Evaluation of Class II Bulk-Fill Restorations in Primary Molars: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Braz. Dent. J. 2022, 33, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantekin, K.; Gumus, H. In Vitro and Clinical Outcome of Sandwich Restorations with a Bulk-Fill Flowable Composite Liner for Pulpotomized Primary Teeth. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 38, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardani, L.; Derchi, G.; Marchio, V.; Carli, E. One-Year Clinical Performance of Activa™ Bioactive-Restorative Composite in Primary Molars. Children 2022, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, P.; Mazzoleni, S.; Parcianello, R.G.; Gatto, R.; Gracco, A.; Stellini, E.; Ludovichetti, F.S. Bulk-Flow Composites in Paediatric Dentistry: Long Term Survival of Posterior Restorations. A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, M.G.; Trentin, G.A.; Noal, F.C.; Franzon, R.; Lenzi, T.L.; de Araujo, F.B. Use of Bulk Fill Resin Composite and Universal Adhesive for Restoring Primary Teeth after Selective Carious Tissue Removal to Soft Dentin: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Dent. 2022, 35, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Olegário, I.C.; Bresolin, C.R.; Pássaro, A.L.; de Araujo, M.P.; Hesse, D.; Mendes, F.M.; Raggio, D.P. Stainless Steel Crown vs Bulk Fill Composites for the Restoration of Primary Molars Post-Pulpectomy: 1-Year Survival and Acceptance Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olegário, I.C.; Moro, B.L.P.; Tedesco, T.K.; Freitas, R.D.; Pássaro, A.L.; Garbim, J.R.; Oliveira, R.; Mendes, F.M.; Raggio, D.P. Use of Rubber Dam versus Cotton Roll Isolation on Composite Resin Restorations’ Survival in Primary Molars: 2-Year Results from a Non-Inferiority Clinical Trial. BMC Oral. Health 2022, 22, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarapultseva, M.; Sarapultsev, A. Flowable Bulk-Fill Materials Compared to Nano Ceramic Composites for Class I Cavities Restorations in Primary Molars: A Two-Year Prospective Case-Control Study. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amend, S.; Boutsiouki, C.; Bekes, K.; Kloukos, D.; Lygidakis, N.N.; Frankenberger, R.; Krämer, N. Clinical Effectiveness of Restorative Materials for the Restoration of Carious Primary Teeth without Pulp Therapy: A Systematic Review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 727–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendicke, F.; Göstemeyer, G.; Blunck, U.; Paris, S.; Hsu, L.-Y.; Tu, Y.-K. Directly Placed Restorative Materials: Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, R.; Mesinger, S.; Opdam, N.; Loomans, B.; Frankenberger, R.; Cadenaro, M.; Burgess, J.; Peschke, A.; Heintze, S.D.; Kühnisch, J. Revised FDI Criteria for Evaluating Direct and Indirect Dental Restorations-Recommendations for Its Clinical Use, Interpretation, and Reporting. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2023, 27, 2573–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durão, M.d.A.; Andrade, A.K.M.d; Santos, M.d.C.M.d.S.; Montes, M.A.J.R.; Monteiro, G.Q.d.M. Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Resin Composite Restorations Using the United States Public Health Service and Federation Dentaire Internationale Criteria: A 12-Month Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquillier, T.; Doméjean, S.; Le Clerc, J.; Chemla, F.; Gritsch, K.; Maurin, J.-C.; Millet, P.; Pérard, M.; Grosgogeat, B.; Dursun, E. The Use of FDI Criteria in Clinical Trials on Direct Dental Restorations: A Scoping Review. J. Dent. 2018, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (First Author, Year) | Postoperative Sensitivity | Aesthetic Evaluation | Secondary Caries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akman, 2020 [11] | Assessed at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months using modified USPHS criteria. No significant difference between materials; all received Alpha scores at all time points. | Evaluated at same intervals using modified USPHS criteria (color match, marginal discoloration, anatomical form). No significant differences; 100% Alpha scores for color match and anatomical form; Equia showed poorer marginal adaptation at 6 and 12 months. | Assessed at all intervals with modified USPHS criteria; 100% success for all groups, no secondary caries detected radiographically. |

| Banon, 2024 [12] | Assessed every 6 months up to 24 months using USPHS-Ryge criteria. No significant differences between materials. | Color match and marginal discoloration assessed every 6 months using USPHS-Ryge. ACTIVA had better color match (p = 0.002), but worse marginal discoloration (p = 0.0143); Dyract showed more color changes over 24 months. | Radiographic evaluation every 12 months; no significant difference between groups. Three Dyract and four ACTIVA restorations developed secondary caries. |

| Deepika, 2022 [13] | Evaluated immediately post-op, at 6 and 12 months. No sensitivity at 12 months; one case at 6 months. | Color match, marginal discoloration, marginal integrity, and anatomic form assessed using modified USPHS. At 12 months, significant differences in marginal discoloration (p = 0.04), marginal integrity (p < 0.001), and anatomic form (p = 0.02), favoring bioactive resin-modified glass ionomer. | Not explicitly listed; no complications (pain, swelling, fistula) at 12 months. |

| Ehlers, 2019 [14] | Baseline and 1 year using FDI criteria. No severe postoperative sensitivities or side effects; both materials clinically excellent. | Baseline and 1 year, FDI criteria (surface luster, staining, color match, translucency, anatomical form). Compomer had better color match and translucency; both materials clinically excellent. | Baseline and 1 year, FDI criteria (recurrence of caries). No secondary caries observed. |

| Gindri, 2022 [15] | Not specifically reported; FDI criteria include biological properties, but postoperative sensitivity was not singled out or discussed as a separate finding. | Assessed at baseline, 6, and 12 months using FDI criteria: surface gloss, surface staining, marginal staining, and anatomical form. No restoration required intervention due to aesthetic parameters; only minor changes observed over 12 months. | Evaluated at baseline, 6, and 12 months using FDI criteria (recurrence of caries). Only one restoration in each group failed due to recurrence of caries after one year; overall, secondary caries was rare. |

| Cantekin, 2014 [16] | Monitored via clinical history of pain reported by parents and children; no pain or symptoms reported at 6 and 12 months; not directly evaluated with scoring system. | Not specifically defined or quantified; aesthetic restorations mentioned but no detailed criteria or results provided. | Evaluated clinically and radiographically for pathological changes and radiolucency; 100% clinical success with no secondary caries at 6 and 12 months. |

| Lardani, 2022 [17] | 3, 6, and 12 months using FDI criteria (biological properties). Slight decrease in “clinically excellent” over time; no significant difference between materials or cavity classes (p = 0.16). | 3, 6, and 12 months, FDI criteria (surface luster, staining, color stability, translucency, anatomic form). Both materials worsened over time; no significant difference (p = 0.19–1). | 3, 6, and 12 months, FDI criteria. Slight decrease in “clinically excellent” restorations; no significant difference between groups. Failure rate at 12 months: 2.2% for both. |

| Lucchi, 2024 [18] | Not assessed long term; sensitivity excluded, as unreliable in pediatric patients. | Color and translucency not considered; marginal dyschromia evaluated visually and with mirror using modified USPHS. Lower incidence in second molars; after 5 years, 37% rated Bravo for superficial marginal dyschromia. | Visual and radiographic assessment with modified USPHS; lower incidence in second molars. After 5 years, 14% of first molars and 13% of second molars had secondary caries. |

| Massa, 2022 [19] | Not reported in the provided data. | Not reported in the provided data. | Not reported in the provided data. |

| Olegário, 2022 (Pulpectomy) [20] | Not directly evaluated as a clinical restoration parameter; parent/child acceptance questionnaire used; child self-assessment with Wong–Baker Faces Pain Scale immediately after treatment; no differences found between groups. | Not evaluated as a clinical restoration parameter; acceptance of appearance assessed by questionnaire; both stainless-steel crowns and bulk-fill composites well accepted by children and parents with no significant difference. | Included as a criterion for restoration success; failures in bulk-fill group related to bulk fracture leading to bacterial infiltration; secondary caries noted in dentin in isolation study; follow-up up to 24 months. |

| Olegário, 2022 (Isolation) [21] | Self-reported pain immediately after treatment (Wong–Baker Faces Pain Scale). No significant difference between groups. | Not a primary outcome; focus on restoration survival, cost, and patient behavior. | Secondary caries in dentine accounted for 25.37% of failures, after bulk fracture (52.24%). |

| Sarapultseva, 2019 [22] | Baseline, 6, 18, 24 months using modified Ryge criteria. No postoperative sensitivity at any point. | Color match, marginal discoloration, surface texture (modified Ryge). No significant differences; two Bravo scores for marginal discoloration in each group. | Baseline, 6, 18, 24 months using modified Ryge. No secondary caries in any restoration; minor difference (3.7%) at 24 months. |

| Oter, 2018 [8] | Baseline, 6 months, 1 year using modified USPHS. Sensitivity higher in bulk-fill at baseline (p < 0.05), resolved by 6 months; no difference at 6 or 12 months. | Color match, marginal discoloration, surface texture, anatomic form (modified USPHS). No significant differences at any interval. Bravo scores for marginal discoloration increased over time in both groups. | Baseline, 6 months, 1 year using modified USPHS. No secondary caries in any group at any time point. |

| Study Type | Focus | Population | Interventions | Comparator | Outcomes Measured | Follow-Up | AMSTAR-2 Rating | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Review | Bulk-fill vs. conventional composites | Primary teeth only | Bulk-fill composites | Conventional composites | Retention, survival, marginal adaptation (qualitative) | 12–84 months | Low | [23] |

| Network Meta-Analysis | Mixed dentition (primary + permanent teeth) | 8/36 studies in primary teeth | Bulk-fill composites | Conventional composites | Survival, failure modes | 24–48 months | Critically Low | [24] |

| Systematic Review | Bulk-fill vs. incremental composites in children | Pediatric, primary teeth only | Bulk-fill composites | Incremental composites | Retention, 2-year survival, marginal integrity, others | 12–60 months | Moderate | Present |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarapultseva, M.; Hu, D.; Sarapultsev, A. Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Versus Incremental Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Evidence. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070320

Sarapultseva M, Hu D, Sarapultsev A. Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Versus Incremental Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Evidence. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(7):320. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070320

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarapultseva, Maria, Desheng Hu, and Alexey Sarapultsev. 2025. "Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Versus Incremental Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Evidence" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 7: 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070320

APA StyleSarapultseva, M., Hu, D., & Sarapultsev, A. (2025). Clinical Performance of Bulk-Fill Versus Incremental Composite Restorations in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Evidence. Dentistry Journal, 13(7), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070320