The Treatment of Gingival Recessions in the Lower Anterior Region Associated with the Use/Absence of Lingual-Fixed Orthodontics Retainers: Three Case Reports Using the Laterally Closed Tunnel Technique and Parallel Incision Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

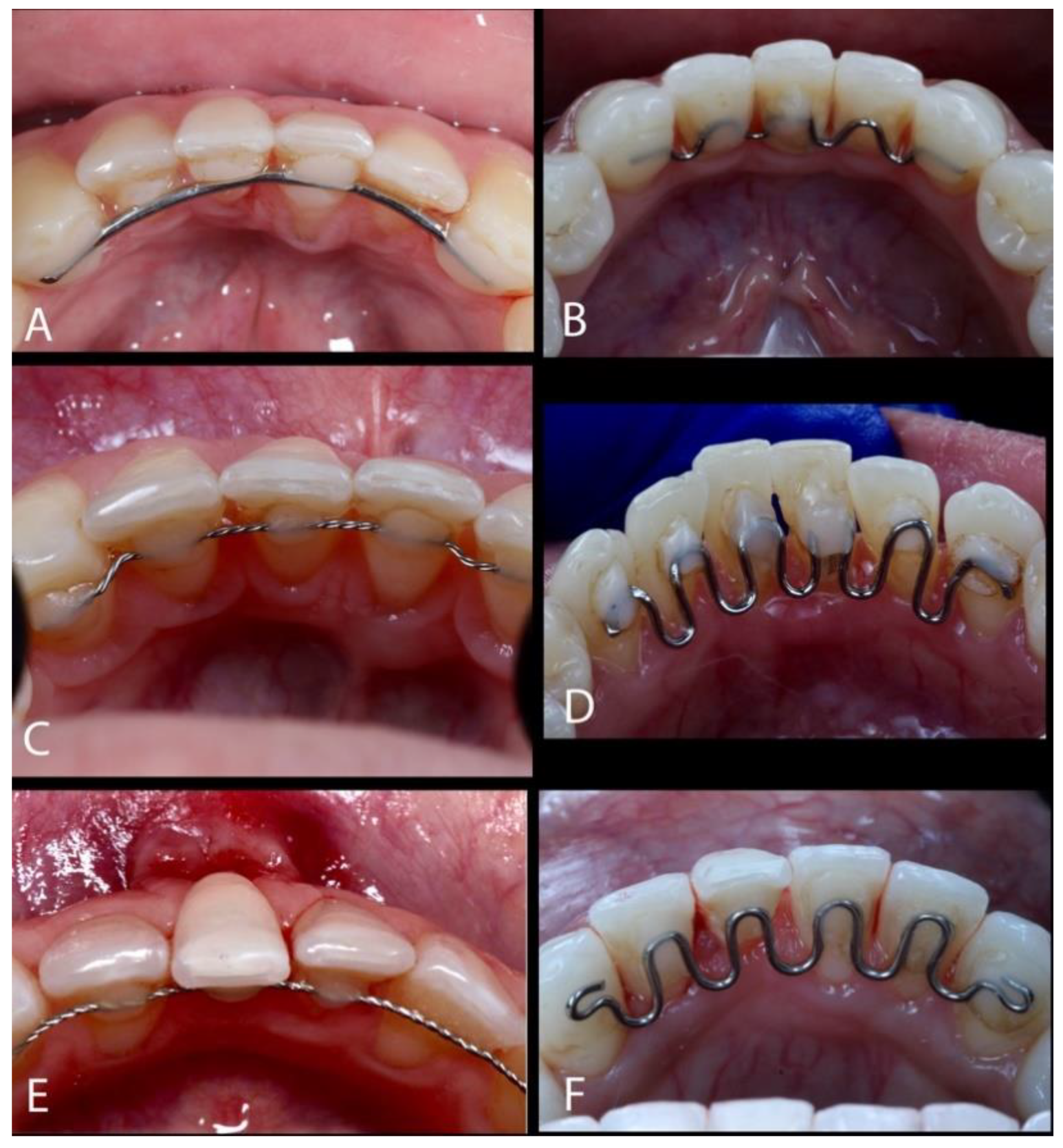

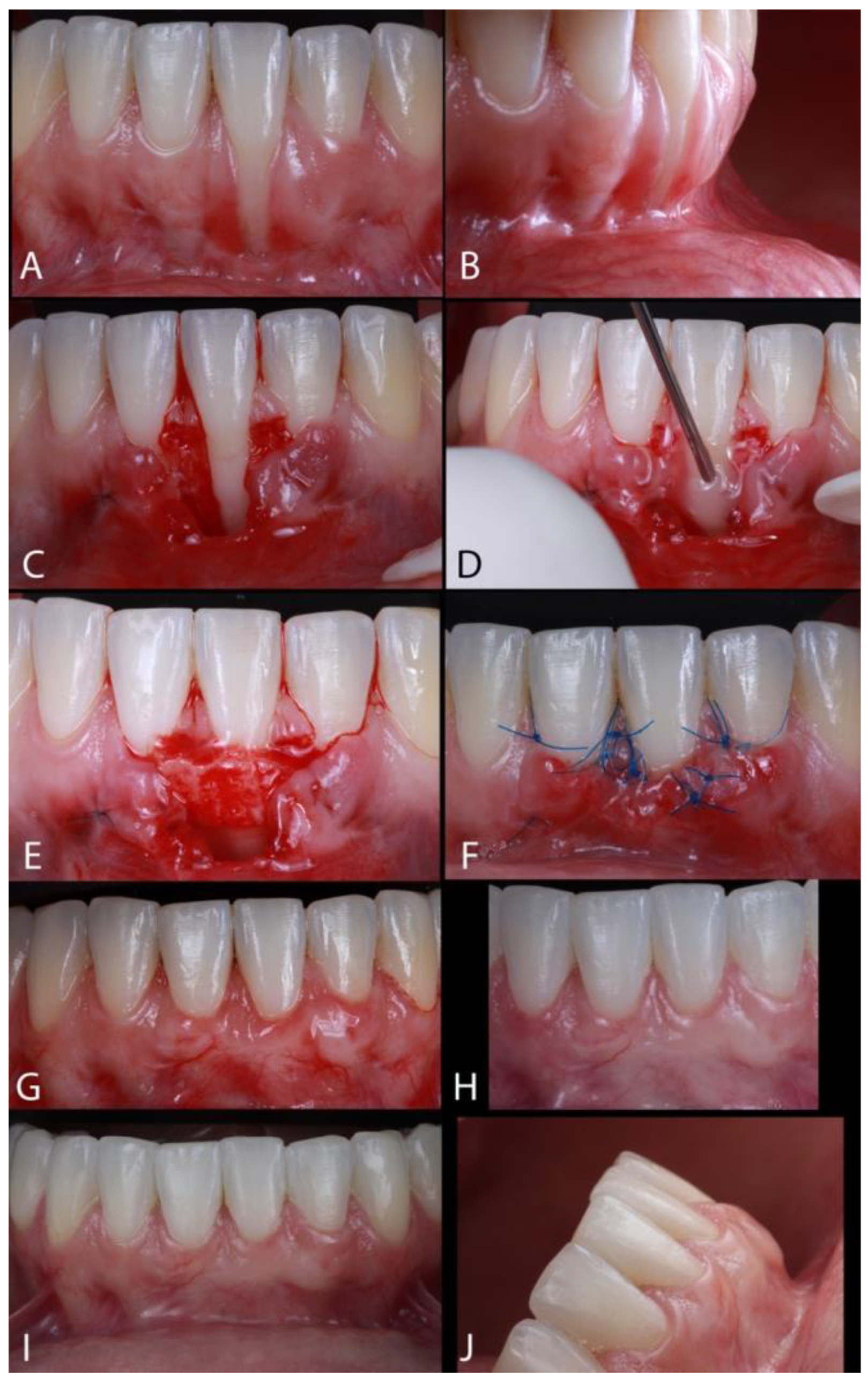

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Plain Language Summary

References

- Cortellini, P.; Bissada, N.F. Mucogingival conditions in the natural dentition: Narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. S1), S204–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troia, P.M.B.P.S.; Spuldaro, T.R.; Fonseca, P.A.B.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Presence of Gingival Recession or Noncarious Cervical Lesions on Teeth under Occlusal Trauma: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2021, 10, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, L.; Samorodnitzky-Naveh, G.R.; Machtei, E.E. The Association of Orthodontic Treatment and Fixed Retainers with Gingival Health. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambrone, L.; Tatakis, D.N. Periodontal soft tissue root coverage procedures: A systematic review from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86 (Suppl. S2), S8–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.S.; Gumber, B.; Makker, K.; Gupta, V.; Tewari, N.; Khanduja, P.; Yadan, R. Global prevalence of gingival recession: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2993–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassab, M.M.; Cohen, R.E. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 134, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juloski, J.; Glisić, B.; Vandevska-Radunovic, V. Long-term influence of fixed lingual retainers on the development of gingival recession: A retrospective, longitudinal cohort study. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, F.S.; Costa, R.S.A.; Moura, M.S.; Jardim, J.J.; Maltz, M.; Haas, A.N. Estimates and multivariable risk assessment of gingival recession in the population of adults from Porto Alegre, Brazil. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsoun, C.F.; Castro, F.; Farsoun, A.; Farsoun, J.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Gingival recession in canines orthodontically aligned: A narrative review. Int. J. Sci. Dent. 2023, 62, 100–121. [Google Scholar]

- Joss-Vassalli, I.; Grebenstein, C.; Topouzelis, N.; Sculean, A.; Katsaros, C. Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: A systematic review. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2010, 13, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djeu, G.; Hayes, C.; Zawaideh, S. Correlation Between Mandibular Central Incisor Proclination and Gingival Recession During Fixed Appliance Therapy. Angle. Orthod. 2002, 72, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.W.; Campbell, P.M.; Tadlock, L.P.; Boley, J.; Buschang, P.H. Prevalence of gingival recession after orthodontic tooth movements. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Venere, D. Correlation between parodontal indexes and orthodontic retainers: Prospective study in a group of 16 patients. Oral Implantol. 2017, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukiantchuki, M.A.; Hayacibara, R.M.; Ramos, A.L. Comparação de parâmetros periodontais após utilização de contenção ortodôntica com fio trançado e contenção modificada. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 2011, 16, 44.e1–44.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moghrabi, D.; Pandis, N.; Fleming, P.S. The effects of fixed and removable orthodontic retainers: A systematic review. Prog. Orthod. 2016, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farret, M.M.; Jamal Hassan Assaf, M.; Martinelli, E. Orthodontic treatment of a mandibular incisor fenestration resulting from a broken retainer. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2015, 148, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifakakis, I.; Pandis, N.; Eliades, T.; Makou, M.; Katsaros, C.; Bourauel, C. In-vitro assessment of the forces generated by lingual fixed retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2011, 139, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charavet, C.; Vives, F.; Aroca, S.; Dridi, S.M. “Wire Syndrome” Following Bonded Orthodontic Retainers: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Healthcare 2022, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, A.M.; Fudalej, P.S.; Renkema, A.; Kiekens, R.; Katsaros, C. Development of labial gingival recessions in orthodontically treated patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2013, 143, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas de Llano-Pérula, M.; Castro, A.B.; Danneels, M.; Schelfhout, A.; Teughels, W.; Willems, G. Risk factors for gingival recessions after orthodontic treatment: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 18, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaughnessy, T.G.; Proffit, W.R.; Samara, S.A. Inadvertent tooth movement with fixed lingual retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, V.T.G.; Kahn, S.; de Souza, A.B.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Deepithelialized Connective Tissue Graft and the Remaining Epithelial Content After Harvesting by the Harris Technique: A Histological and Morphometrical Case Series. Clin. Adv. Periodontics 2021, 11, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, A.T.; Menezes, C.C.; Kahn, S.; Fischer, R.G.; Figueredo, C.M.S.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Gingival recession treatment with enamel matrix derivative associated with coronally advanced flap and subepithelial connective tissue graft: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial with molecular evaluation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sculean, A.; Allen, E.P. The Laterally Closed Tunnel for the Treatment of Deep Isolated Mandibular Recessions: Surgical Technique and a Report of 24 Cases. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2018, 38, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, S.; Araujo, I.T.E.; Dias, A.T.; Souza, A.B.; Chambrone, L.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Histologic and histomorphometric analysis of connective tissue grafts harvested by the parallel incision method: A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing macro- and microsurgical approaches. Quint. Int. 2021, 52, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanini, M.; Mounssif, I.; Marzadori, M.; Mazzotti, C.; Mele, M.; Zucchelli, G. Vertically Coronally Advanced Flap (V-CAF) to Increase Vestibule Depth in Mandibular Incisors. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2021, 41, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, A.M.; Renkema, A.; Bronkhorst, E.; Katsaros, C. Long-term effectiveness of canine-to-canine bonded flexible spiral wire lingual retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthoped. 2011, 139, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.; Walladbegi, J.; Westerlund, A. Effects of fixed retainers on gingival recession—A 10-year retrospective study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennstrom, J.L.; Lindhe, J.; Sinclair, F.; Thilander, B. Some periodontal tissue reactions to orthodontic tooth movement in monkeys. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1987, 3, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.M.; Neiva, R. Periodontal Soft Tissue Non–Root Coverage Procedures: A Systematic Review from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, S56–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, M.; Marzadori, M.; Aroca, S.; Felice, P.; Sangiorgi, M.; Zucchelli, G. Decision making in root-coverage procedures for the esthetic outcome. Periodontol 2000 2018, 77, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavu, V.; Gutknecht, N.; Vasudevan, A.; Balaji, S.; Hilgers, R.; Franzen, R. Laterally closed tunnel technique with and without adjunctive photobiomodula-tion therapy for the management of isolated gingival recession—A randomized controlled assessor-blinded clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent-Bugnas, S.; Borie, G.; Charbit, Y. Treatment of multiple maxillary adjacent class i and ii gingival recessions with modified coronally advanced tunnel and a new xenogeneic acellular dermal matrix. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 30, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.; Sohail, A.; Ahmed, R. Complete root coverage in severe gingival recession with unfavorable prognosis using the tunneling technique. J. Adv. Periodontol. Imp. Dent. 2020, 12, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrushali, A.; David, W.; Jules, M. Treatment of a mandibular anterior lingual recession defect with minimally invasive laterally closed tunneling technique and sub-epithelial connective tissue graft. Int. Arch. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellver-Fernández, R.; Martínez-Rodriguez, A.; Gioia-Palavecino, C.; Caffesse, R.; Peñarrocha, M. Surgical treatment of localized gingival recessions using coronally advanced flaps with or without subepithelial connective tissue graft. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2016, 21, e222–e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, A.; Bourgeois, D.; Katsahian, S.; Mora, F.; Bouchard, P. Risk assessment for buccal gingival recession defects in an adult population. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imber, J.C.; Kasaj, A. Treatment of Gingival Recession: When and How? Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolantonio, M.; di Murro, C.; Cattabriga, A.; Cattabriga, M. Subpedicle connective tissue graft versus free gingival graft in the coverage of exposed root surfaces. A 5-year clinical study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997, 24, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.; Ramos, S.; Santos, N.B.M.; Borges, T.; Montero, J.; Correia, A.; Fernandes, G.V.O. A 3D digital analysis of the hard palate wound healing after free gingival graft harvest: A pilot study in short term. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellini, P.; Pini Prato, G. Coronally advanced flap and combination therapy for root coverage. Clinical strategies based on scientific evidence and clinical experience. Periodontol. 2000 2012, 59, 158–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dias, A.T.; Lopes, J.F.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. The Treatment of Gingival Recessions in the Lower Anterior Region Associated with the Use/Absence of Lingual-Fixed Orthodontics Retainers: Three Case Reports Using the Laterally Closed Tunnel Technique and Parallel Incision Methods. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13030093

Dias AT, Lopes JF, Fernandes JCH, Fernandes GVO. The Treatment of Gingival Recessions in the Lower Anterior Region Associated with the Use/Absence of Lingual-Fixed Orthodontics Retainers: Three Case Reports Using the Laterally Closed Tunnel Technique and Parallel Incision Methods. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(3):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13030093

Chicago/Turabian StyleDias, Alexandra Tavares, Jessica Figueiredo Lopes, Juliana Campos Hasse Fernandes, and Gustavo Vicentis Oliveira Fernandes. 2025. "The Treatment of Gingival Recessions in the Lower Anterior Region Associated with the Use/Absence of Lingual-Fixed Orthodontics Retainers: Three Case Reports Using the Laterally Closed Tunnel Technique and Parallel Incision Methods" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 3: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13030093

APA StyleDias, A. T., Lopes, J. F., Fernandes, J. C. H., & Fernandes, G. V. O. (2025). The Treatment of Gingival Recessions in the Lower Anterior Region Associated with the Use/Absence of Lingual-Fixed Orthodontics Retainers: Three Case Reports Using the Laterally Closed Tunnel Technique and Parallel Incision Methods. Dentistry Journal, 13(3), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13030093