Clinical and Histological Assessment of Knife-Edge Thread Implant Stability After Ridge Preservation Using Hydroxyapatite and Sugar Cross-Linked Collagen: Preliminary Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

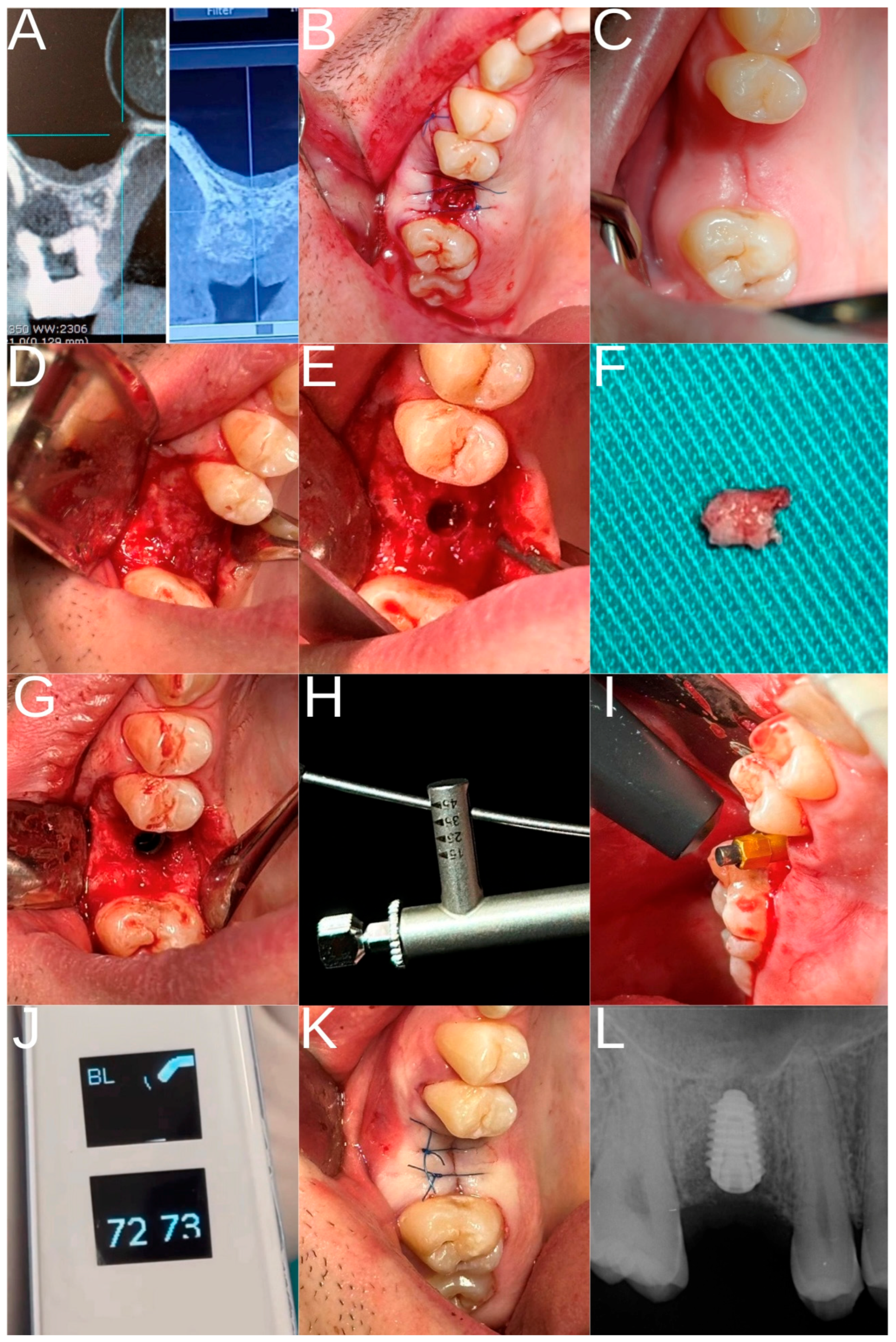

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Study Groups and Surgical Procedure

- Control group: patients who had undergone extraction of the maxillary first molar at least eight months earlier, allowing spontaneous alveolar ridge healing and implant placement.

- Experimental group: patients who had undergone extraction of the maxillary first molar followed by ARP with HSCC and implant placement.

2.4. Postoperative Care

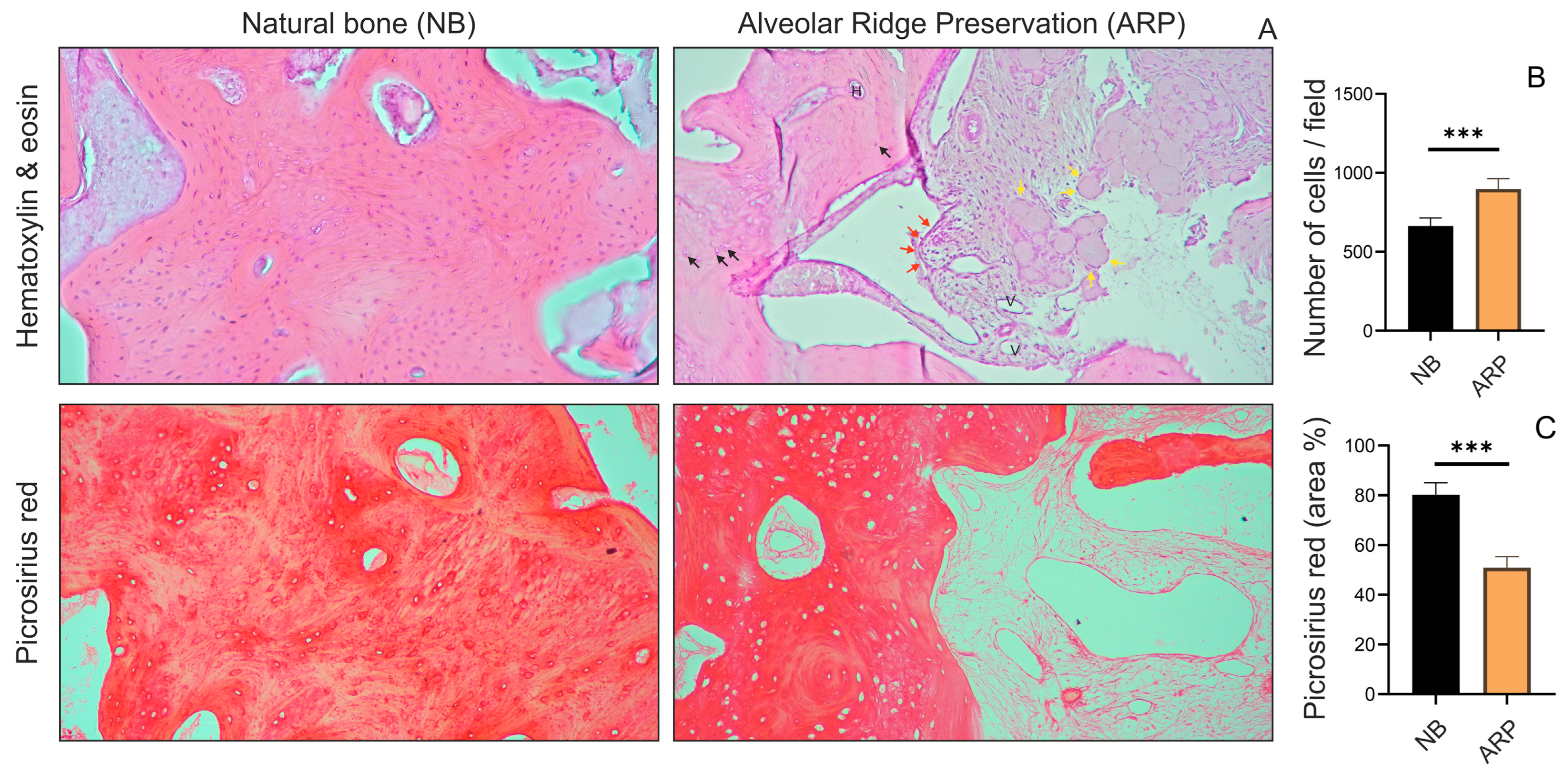

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

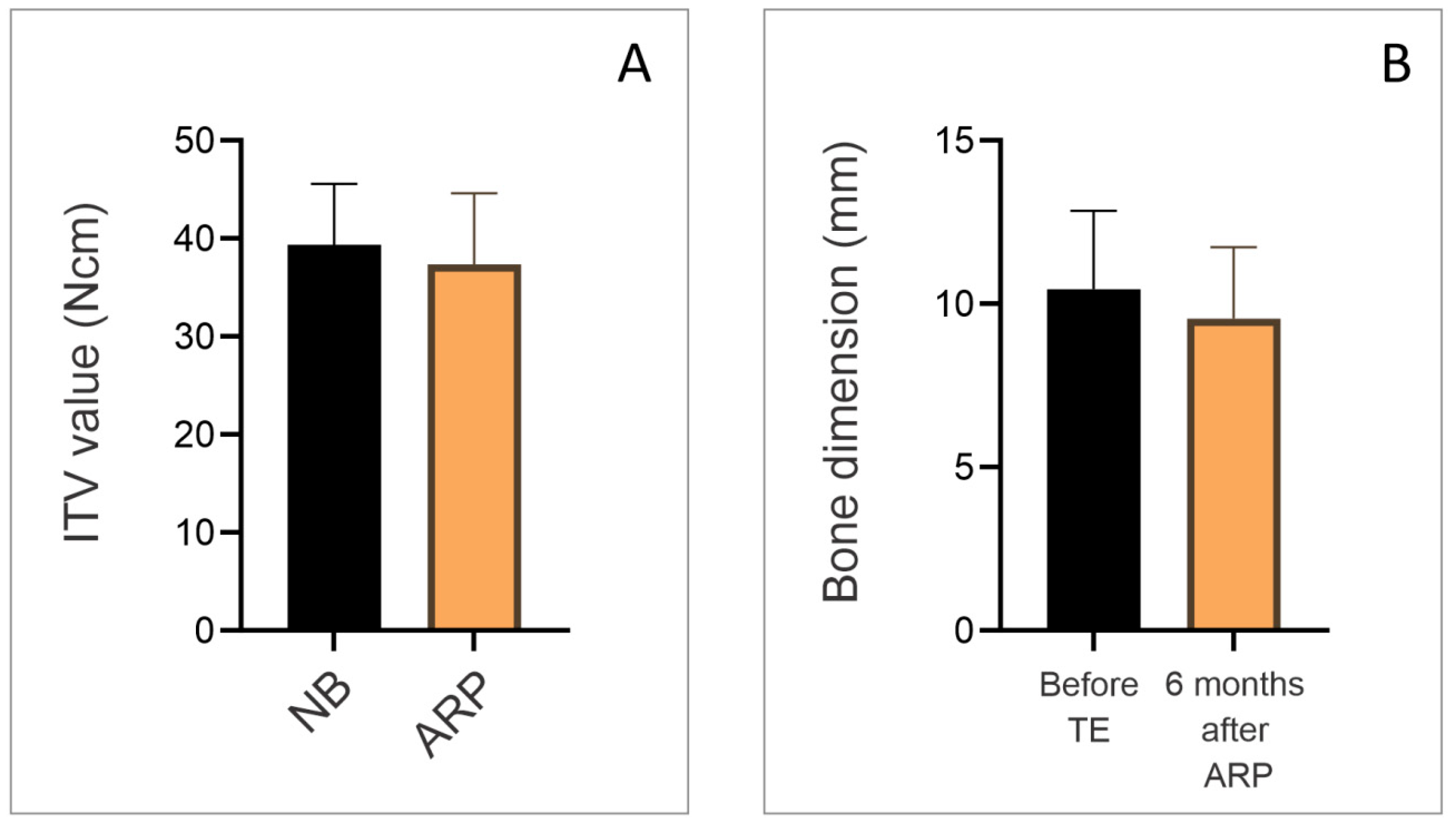

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- ARP with HSCC enables sufficient bone regeneration in terms of quantity and quality within 6 months;

- KTIs provide good primary stability and favorable ITV and ISQ values immediately after placement in the ARP area.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARP | Alveolar ridge preservation |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computer Tomography |

| ISQ | Implant stability quotient |

| ITV | Insertion torque value |

| NB | Natural bone |

| RFA | Resonance frequency analysis |

| KTI | Knife-thread implants |

| HSCC | Hydroxyapatite and sugar cross-linked collagen |

References

- Dardengo, C.d.S.; Fernandes, L.Q.P.; Capelli, J., Jr. Frequency of orthodontic extraction. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2016, 21, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehkalahti, M.M.; Ventä, I.; Valaste, M. Frequency and type of tooth extractions in adults vary by age: Register-based nationwide observations in 2012–2017. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathima, T.; Kumar, M.P.S. Evaluation of quality of life following dental extraction. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2022, 13, S102–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadebo, O.S.; Lawal, F.B.; Sulaiman, A.O.; Ajayi, D.M. Dental implant as an option for tooth replacement: The awareness of patients at a tertiary hospital in a developing country. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2014, 5, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.J.; Prihoda, T.J.; Mealey, B.L.; Lasho, D.J.; Noujeim, M.; Huynh-Ba, G. Evaluation of healing at molar extraction sites with and without ridge preservation: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Cha, J.-K.; Kim, C.-S. Alveolar ridge regeneration of damaged extraction sockets using deproteinized porcine versus bovine bone minerals: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2018, 20, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoonkitvanich, P.; Amornsettachai, P.; Panyayong, W.; Rokaya, D.; Vongsirichat, N.; Suphangul, S. Comparison of the stability of immediate dental implant placement in fresh molar extraction sockets in the maxilla and mandible: A controlled, prospective, non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 54, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Pujia, A.M.; Arcuri, C. Hyaluronic acid combined with ozone in dental practice. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barootchi, S.; Tavelli, L.; Majzoub, J.; Stefanini, M.; Wang, H.L.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Alveolar ridge preservation: Complications and cost-effectiveness. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 92, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, P.; De Rosa, G.; Manicone, P.F.; De Giorgi, A.; Cavalcanti, C.; Speranza, A.; Grassi, R.; D’Addona, A. Hard and soft tissue evaluation of alveolar ridge preservation compared to spontaneous healing: A retrospective clinical and volumetric analysis. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Hong, K.-J.; Ko, K.-A.; Cha, J.-K.; Gruber, R.; Lee, J.-S. Platelet-rich fibrin combined with a particulate bone substitute versus guided bone regeneration in the damaged extraction socket: An in vivo study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayürek, F.; Kadiroğlu, E.T.; Nergiz, Y.; Coşkun Akçay, N.; Tunik, S.; Ersöz Kanay, B.; Uysal, E. Combining platelet rich fibrin with different bone graft materials: Histopathological and immunohistochemical aspects of bone healing. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areewong, K.; Chantaramungkorn, M.; Khongkhunthian, P. Platelet-rich fibrin to preserve alveolar bone sockets following tooth extraction: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, H.; Guo, Y.; Heng, B.C.; Yang, Y.; Yao, W.; Jiang, S. A three-dimensional actively spreading bone repair material based on cell spheroids can facilitate the preservation of tooth extraction sockets. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1161192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisiguiña Salem, C.; Ruiz Delgado, E.; Crespo Reinoso, P.A.; Robalino, J.J. Alveolar ridge preservation: A review of concepts and controversies. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 14, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Couso-Queiruga, E.; Stuhr, S.; Chambrone, L. Long-term outcomes of post-extraction alveolar ridge preservation and reconstruction followed by delayed implant placement: A systematic review. Periodontol. 2000 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abundo, R.; Dellavia, C.P.B.; Canciani, E.; Daniele, M.; Dioguardi, M.; Zambelli, M.; Perelli, M.; Mastrangelo, F. Alveolar ridge preservation with a novel cross-linked collagen sponge: Histological findings from a case report. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashman, A.; Lopinto, J. Placement of implants into ridges grafted with bioplant HTR synthetic bone: Histological long-term case history reports. J. Oral Implantol. 2000, 26, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarian, J.; Shahrabi-Farahani, S.; Ferreira, C.F.; Stewart, C.W.; Luepke, P. Histological evaluation of alveolar ridge preservation using different bone grafts: Clinical study analysis Part II. J. Oral Implantol. 2024, 50, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beca-Campoy, T.; Sánchez-Labrador, L.; Blanco-Antona, L.A.; Cortés-Bretón Brinkmann, J.; Martínez-González, J.M. Alveolar ridge preservation with autogenous tooth graft: A histomorphometric analysis of 36 consecutive procedures. Ann. Anat. 2025, 258, 152375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.W.M.; van Oirschot, B.A.; Jansen, J.A.; van den Beucken, J.J. Innovative implant design for continuous implant stability: A mechanical and histological experimental study in the iliac crest of goats. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 122, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, A.; Barone, S.; Attanasio, F.; Salviati, M.; Cerra, M.G.; Calabria, E.; Bennardo, F.; Giudice, A. Effect of implant macro-design and magnetodynamic surgical preparation on primary implant stability: An in vitro investigation. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Vale Souza, J.P.; de Moraes Melo Neto, C.L.; Piacenza, L.T.; Freitas da Silva, E.V.; de Melo Moreno, A.L.; Penitente, P.A.; Brunetto, J.L.; dos Santos, D.M.; Goiato, M.C. Relation between insertion torque and implant stability quotient: A clinical study. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandini, N.; Kunusoth, R.; Alwala, A.M.; Prakash, R.; Sampreethi, S.; Katkuri, S. Cylindrical implant versus tapered implant: A comparative study. Cureus 2022, 14, e29675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara, S.; Lukosiunas, A.; Dolcini, G.A.; Kubilius, R. Fixed full arches supported by tapered implants with knife-edge thread design and nanostructured, calcium-incorporated surface: A short-term prospective clinical study. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4170537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makary, C.; Menhall, A.; Zammarie, C.; Lombardi, T.; Lee, S.Y.; Stacchi, C.; Park, K.B. Primary stability optimization by using fixtures with different thread depth according to bone density: A clinical prospective study on early loaded implants. Materials 2019, 12, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farronato, D.; Poncia, L.; Vidotto, M.; Maurino, V.; Romano, L. Implant surface variability between progressive knife-edge thread design and ISO thread with and without tapping area: A model analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Amer, M.; Al-Zordk, W.; Mansour, N. Clinical outcomes and implant stability changes associated with immediately loaded implants of two types inserted in the posterior maxilla. Mansoura J. Dent. 2024, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.; Agarwal, S.; Mittal, R.; Rout, S.; Upadhyay, M.; Prince, S.; Suzane, L.; Saini, C.; Gupta, S. Influence of thread geometry and bone density on stress distribution in dental implants: A finite element study. Cureus 2025, 17, e93413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S.; Namgung, C.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, Y.J. The influence of thread geometry on implant osseointegration under immediate loading: A literature review. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2014, 6, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wu, G.; Hunziker, E. The clinical significance of implant stability quotient measurements: A literature review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 10, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavetta, G.; Paderni, C.; Bavetta, G.; Randazzo, V.; Cavataio, A.; Seidita, F.; Khater, A.G.A.; Gehrke, S.A.; Tari, S.R.; Scarano, A. ISQ for assessing implant stability and monitoring healing: A prospective observational comparison between two devices. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansupakorn, A.; Khongkhunthian, P. Implant stability and clinical outcome after internal sinus floor elevation with or without alloplastic graft: A 1-year randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, D.; Lombardi, T.; Colombo, J.; Cervino, G.; Perinetti, G.; Di Lenarda, R.; Stacchi, C. Correlation between insertion torque and implant stability quotient in tapered implants with knife-edge thread design. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7201093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfaraz, H.; Johri, S.; Sucheta, P.; Rao, S. Relationship between insertion torque value and implant stability quotient and its influence on timing of implant loading. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2018, 18, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-C.; Koo, K.-T.; Li, L.; Lee, D.; Lee, Y.-M.; Seol, Y.-J.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, J. Clinical evaluation of implants placed within or beyond the boundaries of alveolar ridge preservation: A 10-week retrospective case series. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2025, 55, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, M.; Ghizzoni, M.; Cusaro, B.; Beretta, M.; Maiorana, C.; Souza, F.Á.; Poli, P.P. High insertion torque—Clinical implications and drawbacks: A scoping review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, P.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Lim, H.-K.; Jia, Q.; Jiang, H.-B.; Lee, E.-S. A six-year prospective comparative study of wide and standard diameter implants in the posterior jaws. Medicina 2021, 57, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raabe, C.; Monje, A.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Buser, D.; von Arx, T.; Chappuis, V. Long-term effectiveness of 6 mm micro-rough implants: A 4.6–18.2-year retrospective study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.R.; Desai, S.R.; Patel, J.R.; Alqhtani, N.R.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Heboyan, A.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Mustafa, M.; Karobari, M.I. Impact of implant diameter and thread design on biomechanics of short implants placed in D4 bone: A finite element analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.J.; Lim, H.C.; Lee, D.W. Alveolar ridge preservation using an open membrane approach for sockets with bone deficiency: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanovic, P.; Selakovic, D.; Vasiljevic, M.; Jovicic, N.U.; Milovanović, D.; Vasovic, M.; Rosic, G. Morphological characteristics of the nasopalatine canal and relationship with anterior maxillary bone: A CBCT study. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Guo, H.; Luo, G.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, C. Clinical applications of concentrated growth factor membrane for socket sealing in alveolar ridge preservation: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokovic, V.; Jung, R.; Feloutzis, A.; Todorovic, V.S.; Jurisic, M.; Hämmerle, C.H. Immediate vs. early loading of SLA implants in the posterior mandible: 5-year randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Ranieri, N.; Miranda, M.; Mehta, V.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G. Mini crestal sinus lift with grafting and simultaneous implant placement in severe maxillary conditions. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2024, 35, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.A.; Bassetti, R.G.; Bosshardt, D.D. The alveolar ridge splitting/expansion technique: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallecillo-Rivas, M.; Reyes-Botella, C.; Vallecillo, C.; Lisbona-González, M.J.; Vallecillo-Capilla, M.; Olmedo-Gaya, M.V. Comparison of implant stability between regenerated and non-regenerated bone: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Hua, Z. Clinical evaluation of maxillary sinus floor elevation with or without bone grafts: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2024, 20, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.M.; Hart, C.N.; Halbritter, S.A.; Morton, D.; Buser, D. Early loading of nonsubmerged titanium implants: 6-month results focusing on crestal bone changes and ISQ. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2009, 11, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltayan, S.; Pi-Anfruns, J.; Aghaloo, T.; Moy, P.K. Predictive value of RFA measurements in implant placement and loading. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, F.; Falter, M. Biomaterial Group Sahlgrenska Academy. In Osstell ISQ Scale Guidelines; Osstel: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016; p. 3. Available online: https://www.osstell.com/clinical-guidelines/the-osstell-isq-scale/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Rodrigo, D.; Aracil, L.; Martin, C.; Sanz, M. Diagnosis of implant stability and its impact on survival: Case series. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2010, 21, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliani, L.; Sennerby, L.; Petersson, A.; Verrocchi, D.; Volpe, S.; Andersson, P. Relationship between RFA and lateral displacement of implants: In vitro study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisi, P.; Carlesi, T.; Colagiovanni, M.; Perfetti, G. ISQ vs micromotion: Effect of bone density and torque. J. Osseointegr. Biomater. 2010, 1, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hicklin, S.P.; Schneebeli, E.; Chappuis, V.; Janner, S.F.M.; Buser, D. Osstell Implant Stability eBook; Osstel: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://criticaldental.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Osstell-Implant-Stability-eBook-The-Guide-to-Monitoring-Implant-Stability_smll.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Adel-Khattab, D.; Afifi, N.S.; Abu El Sadat, S.M.; Aboul-Fotouh, M.N.; Tarek, K.; Horowitz, R.A. Bone regeneration and graft resorption in sockets grafted with SCPC vs nongrafted sites. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2020, 50, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, S.; Kampleitner, C.; Sanz-Esporrin, J.; Lie, S.A.; Gruber, R.; Mustafa, K.; Sanz, M. Regeneration of alveolar defects in pigs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2024, 35, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludovichetti, F.S.; De Biagi, M.; Bacci, C.; Bressan, E.; Sivolella, S. Healing of human critical-size alveolar bone defects after cyst enucleation: A randomized pilot study with 12 months follow-up. Minerva Stomatol. 2018, 67, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veljkovic, L.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Rosic, G.; Selakovic, D.; Jovicic, N.; Stevanovic, M.; Milanovic, J.; Arnaut, A.; Vasiljevic, M.; Milanovic, P. Clinical and Histological Assessment of Knife-Edge Thread Implant Stability After Ridge Preservation Using Hydroxyapatite and Sugar Cross-Linked Collagen: Preliminary Report. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120585

Veljkovic L, Nedeljkovic M, Rosic G, Selakovic D, Jovicic N, Stevanovic M, Milanovic J, Arnaut A, Vasiljevic M, Milanovic P. Clinical and Histological Assessment of Knife-Edge Thread Implant Stability After Ridge Preservation Using Hydroxyapatite and Sugar Cross-Linked Collagen: Preliminary Report. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):585. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120585

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeljkovic, Lidija, Miljana Nedeljkovic, Gvozden Rosic, Dragica Selakovic, Nemanja Jovicic, Momir Stevanovic, Jovana Milanovic, Aleksandra Arnaut, Milica Vasiljevic, and Pavle Milanovic. 2025. "Clinical and Histological Assessment of Knife-Edge Thread Implant Stability After Ridge Preservation Using Hydroxyapatite and Sugar Cross-Linked Collagen: Preliminary Report" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120585

APA StyleVeljkovic, L., Nedeljkovic, M., Rosic, G., Selakovic, D., Jovicic, N., Stevanovic, M., Milanovic, J., Arnaut, A., Vasiljevic, M., & Milanovic, P. (2025). Clinical and Histological Assessment of Knife-Edge Thread Implant Stability After Ridge Preservation Using Hydroxyapatite and Sugar Cross-Linked Collagen: Preliminary Report. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120585