1. Introduction

Insufficient bone height in the posterior maxilla, often caused by alveolar resorption and sinus pneumatization, remains a major challenge for successful implant placement. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation (MSFA) is a predictable surgical technique that restores bone volume and enables implant rehabilitation in these cases [

1,

2]. While autogenous bone remains the “gold standard” because of its osteogenic, osteoconductive, and osteoinductive properties, drawbacks such as donor-site morbidity, unpredictable resorption, extended healing time, and limited availability have prompted the development of alternative grafting materials [

3,

4].

Strontium (Sr) is a natural trace element that shares chemical similarities with calcium and has been shown to enhance bone formation while inhibiting bone resorption [

5]. Strontium ranelate (SrR), a systemic dual-acting bone agent used in osteoporosis therapy, promotes osteoblast differentiation and suppresses osteoclast activity [

6,

7]. Experimental and clinical research has suggested that SrR may improve bone quality and implant osseointegration when incorporated into grafting protocols [

8]. However, limited evidence exists regarding its long-term effects in sinus floor augmentation procedures.

Knowledge gap and study rationale: Although short-term studies have indicated that SrR may enhance bone density and regeneration, few have examined its influence over a decade-long period or compared its performance against conventional sinus augmentation without pharmacological support. Furthermore, little is known about how SrR affects the mechanical quality of regenerated bone over extended periods.

Hypothesis: It was hypothesized that systemic administration of SrR following MSFA would enhance bone density and mechanical strength, leading to improved osseointegration compared with untreated controls.

Objective: The aim of this 10-year preliminary split-mouth study was to evaluate the effects of SrR on bone density, volume, and histological characteristics of grafted maxillary sinuses and to assess its potential as a pharmacological adjunct to traditional augmentation procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This was a prospective, 10-year preliminary split-mouth clinical study designed to evaluate the effects of systemic strontium ranelate (SrR) on bone regeneration following maxillary sinus floor augmentation (MSFA). The study was conducted at the Department of Oral Surgery, Apollonia University, Iași, Romania. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (Approval No.61/28 November 2023), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Patient Selection

Six patients (three women and three men; age range: 46–64 years; mean age: 55.3 years) presenting with bilateral partial edentulous in the posterior maxilla were included. Each patient had an alveolar ridge height of 3–5 mm adjacent to the sinus cavity. Exclusion criteria included metabolic bone disease, systemic osteoporosis, smoking, or medication affecting bone turnover.

2.3. Study Protocol

Each patient underwent two separate sinus augmentation procedures, spaced six months apart, using a split-mouth design. The first surgery was performed on the right maxillary sinus, followed by a six-month regimen of oral strontium ranelate (Osseor, Servier Pharma, Paris, France; 2 g/day). The contralateral sinus was treated without SrR administration and served as the control.

2.4. Surgical Procedure

A lateral window MSFA technique was employed in all cases. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was elevated, and the Schneiderian membrane was carefully reflected. The graft material (Bio-Oss®, Geistlich Pharma AG, Wolhusen, Switzerland; 1–2 mm granules) was mixed with autologous peripheral blood.

Antibiotic protocol: A single intravenous dose of 80 mg gentamicin was administered preoperatively as prophylaxis against infection. Gentamicin use was specific to this experimental protocol to ensure graft site sterility and is not part of standard MSFA practice.

Tetracycline administration: Tetracycline (1 g/day for three days before surgery) was prescribed to label newly formed bone, allowing histological identification of mineralization activity under fluorescence microscopy.

After graft placement, the lateral window was closed with a collagen membrane, and the flap was sutured. Postoperative care included amoxicillin/clavulanate (875/125 mg, twice daily for 5 days), chlorhexidine mouth rinses, and analgesics as needed.

2.5. Radiographic and Clinical Evaluation

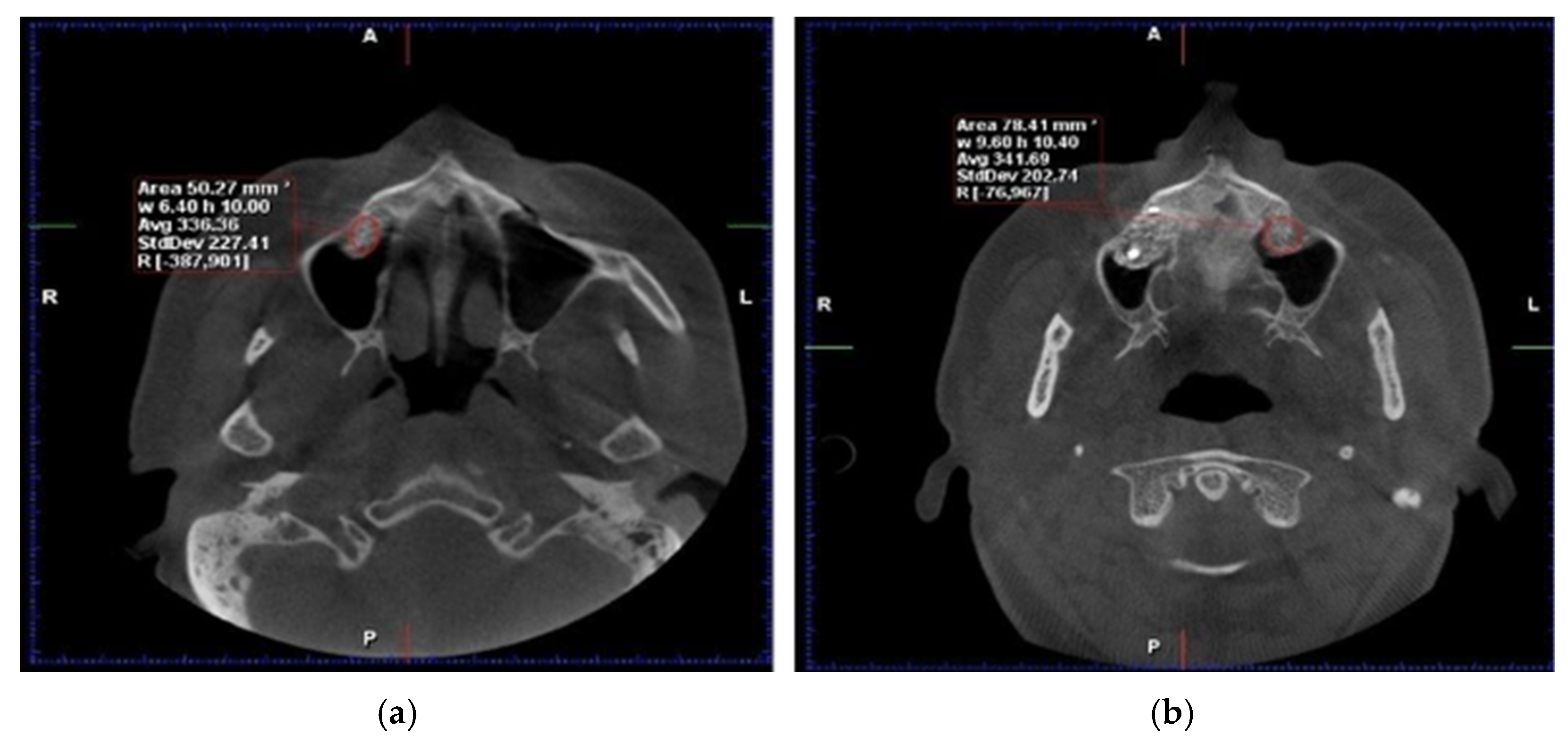

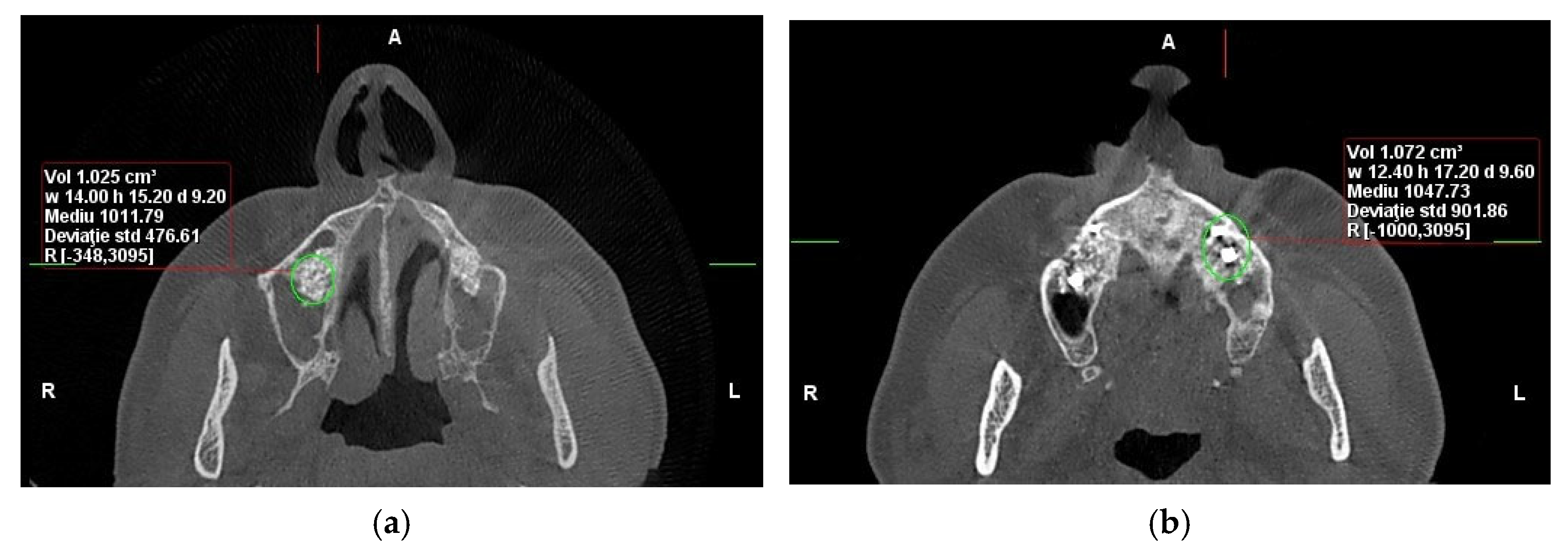

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans were obtained preoperatively, immediately postoperatively, and at 6 months to assess bone volume and density. After six months of healing, bone core biopsies were collected during implant site preparation, and dental implants (Tag Medical Ltd., Kibbutz Ga’aton, Israel) were placed. A follow-up evaluation was performed 10 years after implant placement to assess long-term outcomes, including implant survival and patient-reported satisfaction. The primary analysis in this study was based on imaging and biopsy results collected within the first six months. (

Figure 1). However, the 10-year follow-up data focused on long-term implant success and patient-reported outcomes rather than additional CBCT or biopsy examinations (

Figure 2).

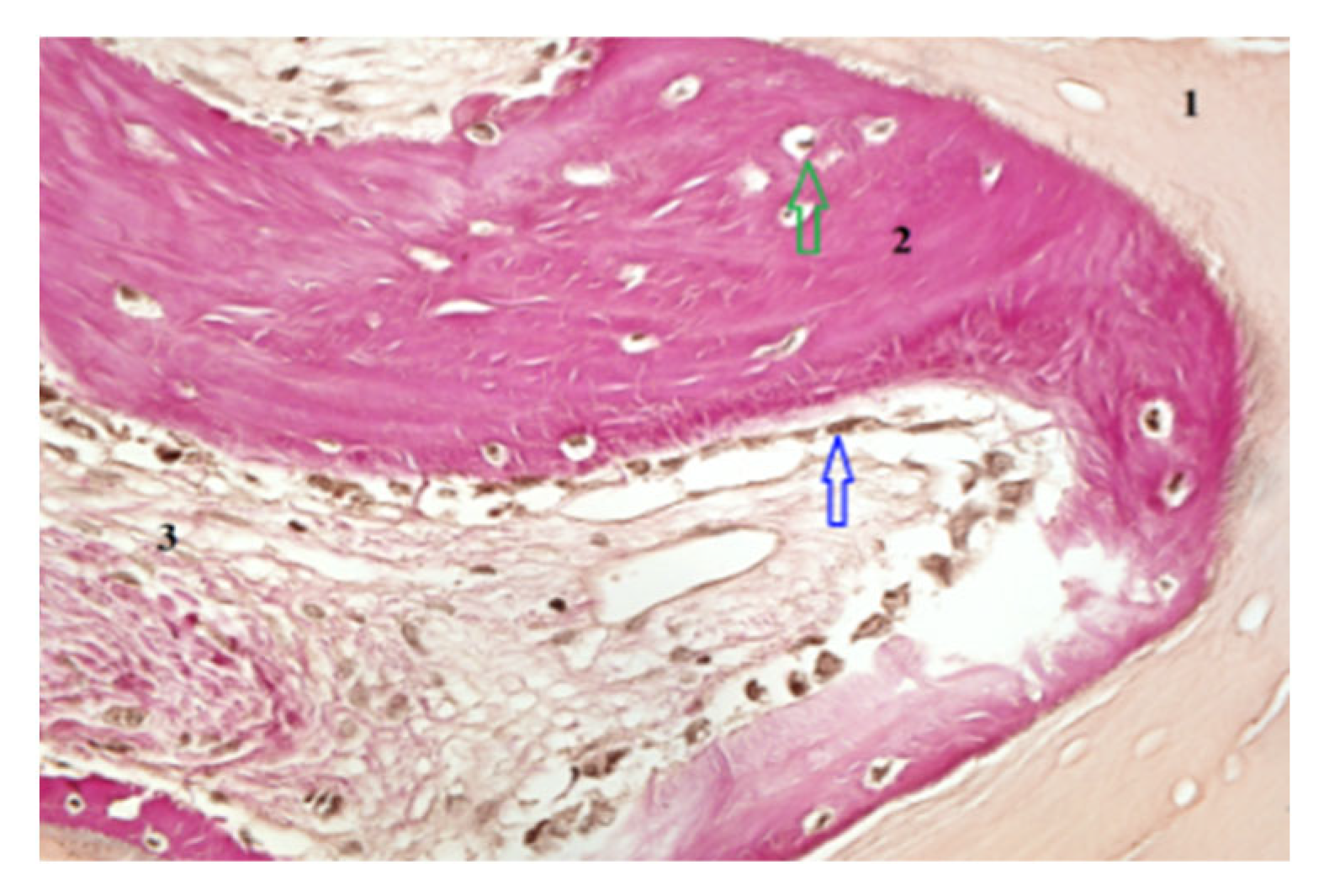

2.6. Histological and Mechanical Analysis

Biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, decalcified, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Von Gieson (VG) staining. Histomorphometric analysis quantified the percentage of newly formed bone, residual graft particles, and connective tissue using digital microscopy (Zeiss AxioObserver Z1, Viena Austria- Manufactur- Zeiss) and HistoQuest software version 7 (TissueGnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria). Mechanical properties were assessed by microindentation testing to determine bone hardness and elasticity. For histomorphometric analysis, representative areas of interest—newly formed bone, xenograft particles, and stromal tissue—were carefully outlined at a scale of 400/700 µm. Consistent criteria were applied across the entire patient group to demarcate the boundaries of newly formed bone, xenograft material, and stromal tissue. This ensured reproducibility and accuracy of the measurements for each tissue type (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics v27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data normality was verified with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Paired

t-tests were used for normally distributed data (bone density and hardness), while nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to non-normally distributed datasets (bone volume and histomorphometric ratios). Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05. Given the small sample size (

n = 6), both tests were used complementarily to ensure analytical robustness. (

Table 1)

3. Results

3.1. Postoperative Outcomes

All patients healed uneventfully following both augmentation procedures. Mild postoperative edema and discomfort were noted but resolved within several days. No cases of infection, sinus membrane perforation, or implant failure occurred during the 10-year observation period. All implants remained functionally stable and clinically successful.

3.2. Bone Density

At six months postoperatively, CBCT analysis revealed higher mean bone density in SrR-treated sites compared with untreated controls. Over the 10-year follow-up period, SrR-treated quadrants demonstrated a mean increase of 22.94% in bone density, whereas control quadrants showed a 12.51% increase.

The Hounsfield Unit (HU) values remained consistently higher in SrR sites throughout the follow-up period, confirming a sustained enhancement in mineralization (

Table 2).

At 10 years, 66.7% of SrR-treated sites demonstrated a continued increase in density compared with only 20% of controls.

These findings indicate that systemic SrR administration significantly improved bone density and mineral quality over time.

3.3. Bone Volume

At six months, bone volume measurements were similar between groups. After 10 years, a gradual decrease was observed in both, consistent with physiological remodeling.

The SrR-treated group exhibited a 13.32% mean reduction in bone volume, whereas the control group showed a 12.82% reduction (

Table 3).

Although SrR administration did not prevent volume loss, the rate of reduction was slightly lower in the treated sites, indicating partial preservation of grafted bone architecture.

3.4. Histological and Histomorphometric Findings

Histological examination revealed active osteogenesis in both SrR and control sites. However, SrR-treated specimens exhibited more mature lamellar bone, denser trabeculae, and reduced residual graft material.

Quantitative histomorphometry showed that SrR-treated samples contained 46–55% newly formed bone, 15–20% residual graft particles, and 25–30% connective tissue, compared with 35–42% new bone, 25–30% graft material, and 30–35% connective tissue in untreated controls.

The results indicate a higher degree of mineralization and bone maturation in the SrR group.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate these histological differences. Scale bars and tissue labels have been standardized to improve figure clarity.

3.5. Mechanical Properties

Microindentation tests demonstrated that SrR-treated bone exhibited superior hardness and elasticity compared with untreated bone. The mean hardness increase corresponded to improved bone microarchitecture and mineral integration. These results align with the higher bone density observed radiographically (

Table 4).

3.6. Explanation of Missing Data

In

Table 5, certain missing values (“?”) correspond to samples in which insufficient bone material was available for microindentation testing due to limited biopsy size. These instances have been clearly indicated in the table footnotes to ensure transparency.

4. Discussion

This 10-year split-mouth clinical study evaluated the long-term impact of systemic strontium ranelate (SrR) on bone regeneration following maxillary sinus floor augmentation (MSFA). The findings demonstrate that SrR enhanced bone density and mechanical strength of grafted bone but had a limited effect on long-term volume preservation. Although preliminary due to the small sample size, these results suggest that SrR may serve as a useful pharmacological adjunct for improving bone quality in implantology.

4.1. Interpretation of Main Findings

SrR administration produced a mean 22.9% increase in bone density compared with 12.5% in untreated sites, confirming the material’s osteogenic potential. Histological analyses further revealed a higher proportion of lamellar bone and reduced residual graft particles in SrR-treated specimens. The improved microhardness and elasticity observed align with SrR’s known dual mechanism—stimulating osteoblast differentiation while suppressing osteoclast activity [

6,

7].

Despite these benefits, SrR did not prevent the moderate bone volume reduction observed over the decade. This suggests that while SrR enhances the quality of regenerated bone, it may not significantly influence long-term quantity, which depends on broader biomechanical and remodeling processes.

Clinical Implications of Bone Density and Volume Changes

The observed increase in bone density in SrR-treated sites, particularly over the 10-year period, holds significant clinical implications for implantology. Bone density is a critical determinant of implant stability and osseointegration, especially in patients with compromised bone quality. This study’s results demonstrate that SrR can effectively improve bone density over a long period, suggesting its potential as an adjunct treatment to improve implant outcomes, particularly in maxillary sinus augmentations where bone deficiency is prevalent [

8,

9].

However, despite the positive effects on density, both groups exhibited a decrease in bone volume over time, indicating that bone resorption continues to occur even in the presence of SrR. This highlights the importance of bone volume preservation for long-term implant success. In clinical practice, bone volume loss may compromise implant placement, and SrR alone may not be sufficient to maintain volume over the long term. Adjunctive therapies that enhance bone volume and quality are therefore essential to optimize outcomes in these cases [

10].

However, while the SrR-treated group showed improvements in bone density, both groups (with and without SrR) exhibited similar reductions in bone volume over time. Thus, while SrR is beneficial for improving bone quality, its role in preserving bone volume over the long term appears limited. These findings underscore the need for complementary therapies to address bone volume loss, as suggested by Yan et al., who explored the use of bioactive materials alongside SrR for improved bone regeneration [

11].

4.2. Comparison with Contemporary Technques

Recent innovations in MSFA and ridge reconstruction highlight evolving strategies to minimize grafting and optimize healing.

Menchini-Fabris et al. (2020) proposed distal displacement of the anterior sinus wall as a minimally invasive alternative to the lateral approach, reducing the need for grafting materials [

12]. In contrast, the present study focuses on pharmacological enhancement of bone formation rather than surgical modification.

Cosola et al. (2022) demonstrated successful sinus elevation using absorbable collagen alone, underscoring a trend toward graft simplification [

13]. The SrR-based approach differs by augmenting osteogenesis biochemically rather than mechanically or by biomaterial reduction.

Crespi et al. (2021) described the split-crest technique for ridge expansion without sinus elevation [

14]. When viewed alongside such alternatives, SrR administration represents an adjunctive systemic strategy that could complement rather than replace these minimally invasive surgical methods.

Potential Adjunct Therapies to Prevent Bone Volume Loss

Several adjunct therapies have been proposed in recent years to address bone volume loss in sinus augmentation procedures. The combination of SrR with bone grafts, such as xenografts, allografts, or autografts, can potentially provide both structural support and biological stimulation to enhance bone regeneration. Additionally, the use of bioactive materials such as collagen scaffolds and chitosan has been shown to improve cellular attachment and osteogenesis in bone grafts, and combining these materials with SrR may enhance both bone volume and density [

15,

16]. Growth factors such as Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) have also demonstrated potential in accelerating bone healing and reducing bone resorption during the remodeling phase [

17].

Furthermore, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), particularly BMP-2 and BMP-7, have been shown to significantly promote bone formation and regeneration in areas of bone deficiency, suggesting that their combination with SrR could help overcome the limitations of SrR in maintaining bone volume [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Another promising adjunct therapy is the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are increasingly being used for their osteogenic potential in enhancing bone regeneration and healing [

23,

24]. Recent studies suggest that combining SrR with additional treatments may help prevent bone volume loss Aroni et al explored the potential of combining SrR with autografts, showing improved bone quality and implant success rates [

25].

4.3. Additional Biological Considerations

Systemic factors such as vitamin D status can markedly influence bone metabolism, mineralization, and implant osseointegration. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with delayed bone healing and lower implant stability. Although vitamin D levels were not evaluated in this study, their potential confounding effect warrants consideration in future investigations, as adequate vitamin D supplementation may synergize with SrR to enhance bone regeneration outcomes.

4.4. Study Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size (n = 6), which restricts statistical power and generalizability. Furthermore, the absence of quantitative clinical outcomes—such as implant survival rates, implant stability quotient (ISQ) measurements, and patient-reported satisfaction—prevents a comprehensive assessment of long-term functional success. Additionally, the observational design precludes causal inference, and the lack of vitamin D evaluation or standardized dietary control could have influenced the observed variability in bone density.

4.5. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Despite these constraints, the results suggest that systemic SrR may improve the quality of regenerated bone, which could translate to enhanced implant stability in patients with compromised bone. Future research should employ larger, multicenter randomized trials, incorporate detailed clinical outcomes, and explore combined interventions (e.g., SrR with vitamin D supplementation or biologically active graft materials). Longitudinal imaging and mechanical assessments will also be essential to confirm the durability of SrR’s effects beyond the 10-year window presented here.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this small preliminary study, the systemic administration of strontium ranelate (SrR) following maxillary sinus floor augmentation enhanced bone density and mechanical strength around dental implants without significantly affecting long-term bone volume preservation. These findings indicate that SrR may serve as a valuable pharmacological adjunct for improving bone quality and osseointegration in the posterior maxilla, particularly in patients with reduced bone density.

However, the restricted sample size (n = 6) and the absence of implant stability and patient-reported outcome data limit the generalizability of the results. Future multicenter studies with larger, more diverse populations—incorporating implant survival, stability measurements (ISQ), and quality-of-life indicators—are necessary to validate and expand upon these promising preliminary observations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.G. and E.D.; methodology, E.D.; software, E.D. and G.M.; validation, E.D., D.H. and G.M.; formal analysis, E.D. and D.H.; investigation, E.D., D.H. and G.M.; resources, M.G.; data curation, E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G.; visualization, E.D., D.H. and G.M.; supervision, E.D.; project administration, E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lutz, R.; Berger-Fink, S.; Stockmann, P.; Neukam, F.W.; Schlegel, K.A. Sinus floor augmentation with autogenous bone vs. a bovine-derived xenograft: A 5-year retrospective study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spin-Neto, R.; Stavropoulos, A.; Coletti, F.L.; Pereira, L.A.; Marcantonio, E., Jr.; Wenzel, A. Remodeling of cortical and corticocancellous fresh-frozen allogeneic block bone grafts: A radiographic and histomorphometric comparison to autologous bone grafts. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentleman, E.; Fredholm, Y.C.; Jell, G.; Lotfibakhshaiesh, N.; O’Donnell, M.D.; Hill, R.G.; Stevens, M.M. Effects of strontium-substituted bioactive glasses on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in vitro. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3949–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marie, P.J.; Felsenberg, D.; Brandi, M.L. How strontium ranelate prevents osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, P.J.; Roux, C.; Seeman, E.; Ortolani, S.; Badurski, J.E.; Spector, T.D.; Cannata, J.; Balogh, A.; Lemmel, E.M.; Pors-Nielsen, S.; et al. The effects of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.Z.; Offermanns, V.; Sillassen, M.; Almtoft, K.P.; Andersen, I.H.; Sørensen, S.; Jeppesen, C.S.; Kraft, D.C.; Bøttiger, J.; Rasse, M.; et al. Accelerated bone ingrowth by local delivery of strontium from surface-functionalized titanium implants. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5883–5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, D.; Beretta, M.; Bianchi, L. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin in bone regeneration and implantology. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.T.A.; Carvalho, J.L.P.; Paranhos, L.R.; Bernardino, I.M.; Moura, C.C.G.; Irie, M.S.; Soares, P.B.F. Use of platelet-rich fibrin for bone repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ressler, A. Chitosan-based biomaterials for bone tissue engineering—A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Escudero, N.D.; Mandalunis, P.M. Effect of strontium ranelate on bone remodeling. Actaodontol. Latinoam. 2012, 25, 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.D.; Ou, Y.J.; Lin, Y.J. Does the incorporation of strontium into calcium phosphate improve bone repair? A meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchini-Fabris, G.B.; Toti, P.; Crespi, G.; Covani, U.; Crespi, R. Distal displacement of the maxillary sinus anterior wall versus conventional sinus lift with lateral access: A 3-year retrospective CT study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosola, S.; Di Dino, B.; Traini, T.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, Y.M.; Marconcini, S.; Covani, U.; Vinci, R. Radiographic and histomorphologic evaluation of the maxillary bone after crestal mini-sinus lift using absorbable collagen. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, R.; Toti, P.; Covani, U.; Crespi, G.; Menchini-Fabris, G.B. Maxillary and mandibular split-crest technique with immediate implant placement: A 5-year CBCT study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2021, 36, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yang, R.; Cooper, P.R.; Khurshid, Z.; Shavandi, A.; Ratnayake, J. Bone grafts and bone substitutes in dentistry: A review of current trends and developments. Molecules 2021, 26, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkas, A.; Wilde, F.; Heufelder, M.; Winter, K.; Schramm, A. Autogenous bone grafts in oral implantology—Is it still a “gold standard”? A systematic review. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2017, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, M.; Born, G.; Chaaban, M.; Scherberich, A. Natural Polymeric Scaffolds in Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Donos, N.; Mardas, N.; Boora, P. Bone regeneration in implant dentistry: Which are the factors affecting outcomes? Periodontology 2000 2023, 91, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziejska, B.; Stępień, N.; Kolmas, J. The influence of strontium on bone tissue metabolism and its application in osteoporosis treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavelli, L.; Ravidà, A.; Barootchi, S.; Chambrone, L.; Giannobile, W.V. Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor: A systematic review of clinical findings in oral regenerative procedures. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2021, 21, 101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Peng, R.; Huang, F.; Hong, L.; Chen, W. Antibiotic-loaded bone substitutes therapy in the management of moderate to severe diabetic foot infection: A meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2023, 31, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukpaita, T.; Chirachanchai, S.; Pimkhaokham, A.; Ampornaramveth, R.S. Chitosan-Based Scaffold for Mineralized Tissues Regeneration. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpinde, M.R.; Pundkar, A.; Shrivastava, S.; Patel, H.; Chandanwale, R. A comprehensive review of platelet-rich plasma and its emerging role in accelerating bone healing. Cureus 2024, 16, e54122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giro, G.; Chambrone, L.; Goldstein, A.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Zenóbio, E.; Feres, M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Cassoni, A.; Shibli, J.A. Impact of osteoporosis in dental implants: A systematic review. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aroni, M.A.; Tampieri, A.; Berlutti, F.; Chiesa, R.; Iafisco, M.; Prati, C.; Martini, D. Loading Deproteinised Bovine Bone with Strontium Improves Bone Regeneration in Maxillary Sinus Augmentation: A Preclinical Study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).