1. Introduction

Sulfur hexafluoride, SF

6, is a colorless, nonflammable and highly inert gas with an extremely high global warming potential (GWP) [

1,

2]. Because of its excellent electric characteristics and high chemical stability, it is used as a dielectric medium in high-voltage circuit breakers, transformers, capacitors and many more industrial applications [

3]. Since the search for a replacement material that is less harmful to the environment or that is easier to dispose of has not yet been successful, the decomposition of sulfur hexafluoride remains a current field of research [

4,

5,

6].

The activation of SF

6 was first shown in the literature in 1900 by Moissan and Lebeau [

7]. They described the reaction between sulfur hexafluoride and hydrogen sulfide to sulfur and hydrogen fluoride. Furthermore, reactions with elemental sodium at 200 °C and several catalytic activations with nickel- or rhodium-complexes of SF

6 have been published [

4,

5,

8].

The reaction between SF

6 and sodium, dissolved in liquid ammonia, was reported in 1964 by Demitras and MacDiarmid; however, they were not able to identify the products [

9]. The reaction between SF

6 and caesium in liquid ammonia at −61 °C gave several good hints as to the formation of CsF and Cs

2S [

10].

During the reaction of ⅛ mol SF6 per 1 mol of Cs, they observed that the blue colour of the solution of Cs in NH3 disappeared. The weight of the products compared to the weight of the reactants showed a ratio close to 1.14. This would be the expected ratio for the postulated reaction according to Equation (1). Dissolving the white-appearing products in water and adding some HCl leads to the formation of H2S, which also represents an indication for the postulated reaction.

In the present work, the reaction between metals that dissolve in liquid ammonia at −60 °C and internal pressure and SF6 were investigated in detail.

2. Results and Discussion

The reactions between the alkali metals dissolved in liquid ammonia and SF

6 lead to the formation of the respective products (Equation (2)) that Demitras and MacDiarmid predicted for the reaction of Cs dissolved in NH

3 with SF

6.

The mono- or bivalent fluorides and sulfides could be obtained at −50 °C at reaction times ranging from nearly one to two and a half hours. The results are presented in the form of selected examples.

2.1. Alkali Metals (Li–Cs)

The conversion of SF

6 into alkali metal fluorides and the respective sulfides of the form M

IF and M

I2S took between 50 min for caesium (4.9 mmol) and 135 min for sodium (38 mmol). The reaction times and turnover rates for the reaction are shown in

Table 1. During the reaction the blue to bronze colors of the solutions changed slowly to a light brownish white. The reaction rates did not correspond to the trend of rising reactivity of the alkali metals from Li to Cs, and the influence of the liquid ammonia solvent is also not clear. A precise control of the SF

6 gas flow by a flowmeter was not carried out.

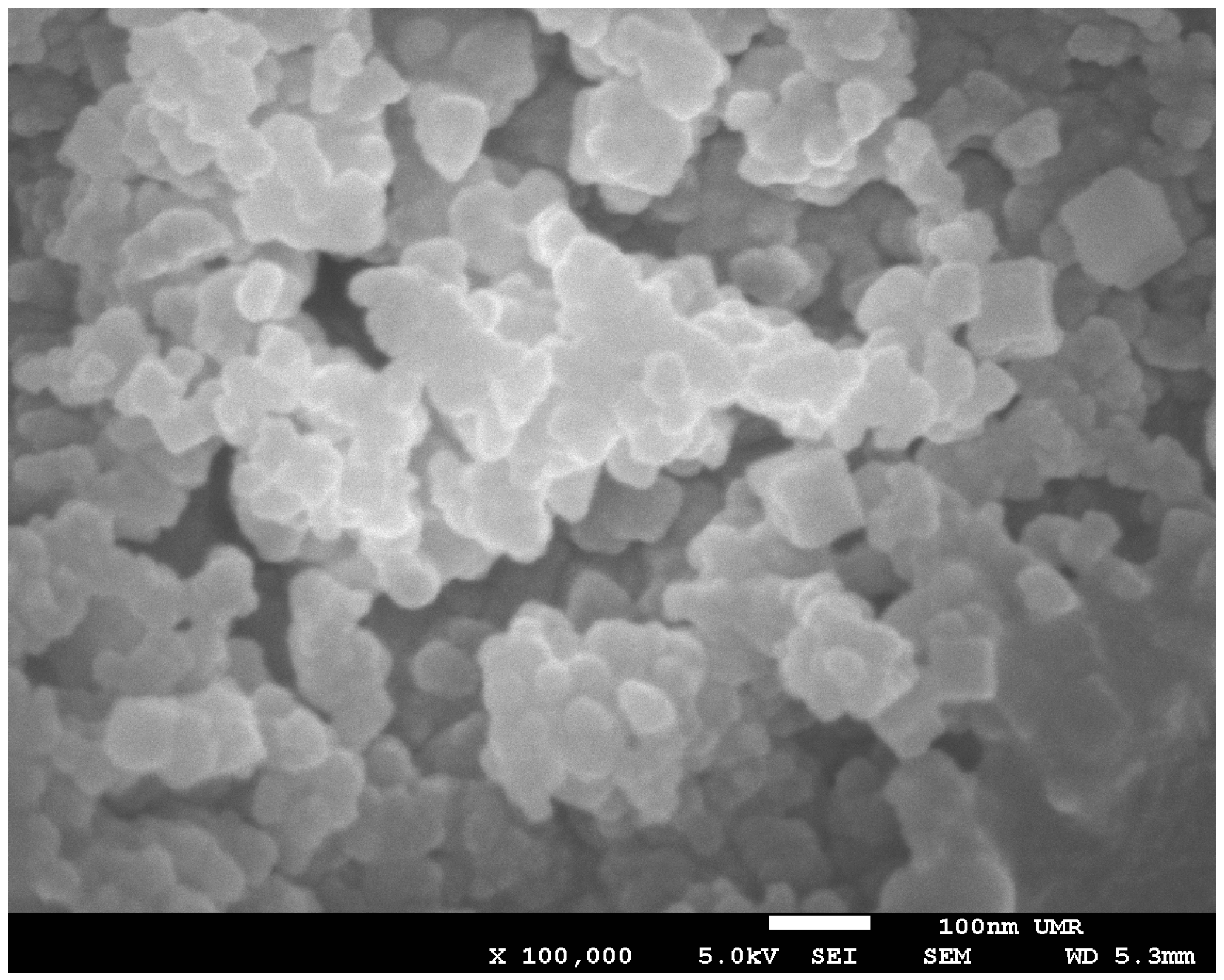

After slowly removing the liquid ammonia under vacuum, a dark white to light brown powder remained in the Schlenk vessel. The powders were dried under vacuum at room temperature, and a powder X-ray diffraction pattern was recorded. The patterns showed rather broad reflexes over a large 2θ-range. A possible explanation for the broad reflexes are the small particle sizes. Recording an image with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) showed small particles with a diameter around or below 100 nm. One of these images of the product of the reaction between SF

6 and sodium is shown in

Figure 1, and indicates a nano powder of NaF and Na

2S.

For a better crystallization of the samples, a few hundred milligrams of the reaction mixture were sealed in a borosilicate tube and annealed under vacuum at 450 °C for five days. After crystallization, all X-ray powder diffraction patterns clearly showed the formation of the respective alkali metal fluoride MIF. For sodium, potassium and rubidium, the characteristic reflections for the alkali metal sulfide MI2S were also observable. In some cases, the formation of the alkali metal amides as a byproduct was able to be shown by powder X-ray diffraction. For the reactions with lithium and caesium, the diffraction pattern only showed the formation of the respective fluoride and remnants of lithium metal. To prevent the formation of elemental sulfur, the powder was sealed into a borosilicate glass tube under vacuum (1.5 × 10−3 mbar) at a temperature gradient from 450 °C to room temperature. Because of its reactivity with glass, the products of the reaction between Li and SF6 were sealed in a tantalum tube. A sublimation of elemental sulfur could not be observed. Another proof was the release of H2S when immersed in diluted HCl, as shown by the blackening of moist Pb(CH3COO)2 paper.

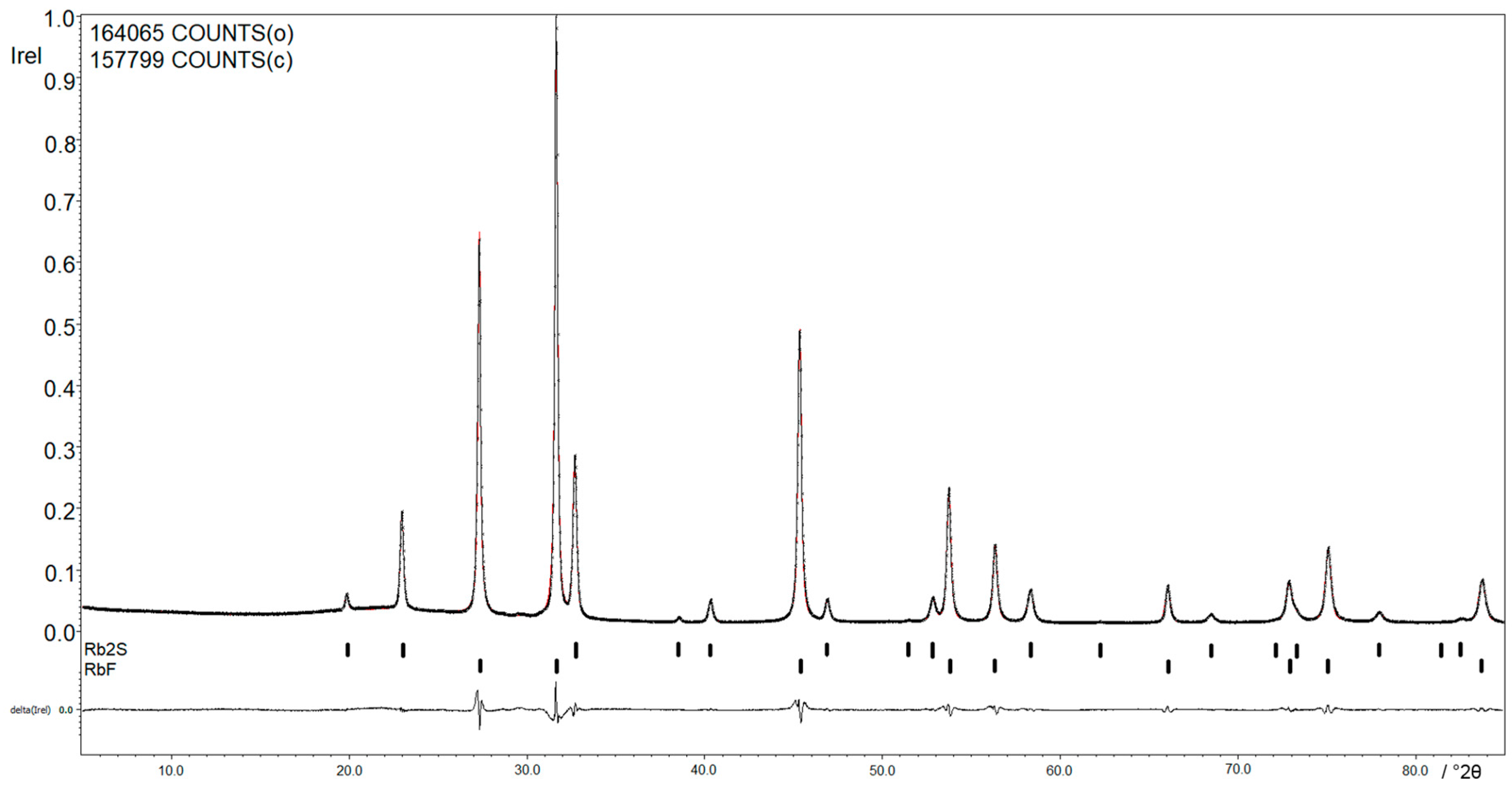

Figure 2 shows the X-ray powder diffraction pattern of the reaction between Rb and SF

6. The

Rietfeld refinement of the products, RbF and Rb

2S, shows a relation of RbF:Rb

2S of 88.0(1):12.0(1), which corresponds to the predicted value of 86:14. The lattice parameters are with

a = 5.6586(1) Å,

V = 181.187(4) Å

3 for RbF and

a = 7.7533(2) Å,

V = 466.080(8) Å

3 for Rb

2S in accordance with the results reported in the literature [

11,

12].

As should be expected, the ATR IR spectrum of the mixture of RbF and Rb

2S (

Figure S1) shows no bands in the range from 4000 to 400 cm

−1. An IR band of RbF should be observed at 376 cm

−1, so there is no IR activity expected in the measured region [

13]. The measured intensities between 2200 and 1900 cm

−1 are characteristic for the ATR diamond module.

2.2. Alkaline Earth and Rare Earth Metals (Sr, Ba, Eu, Yb)

The conversion of SF

6 into the fluorides and sulfides of the form M

IIF

2 and M

IIS with alkaline earth and rare earth metals took place for Ba, Sr and Eu, according to Equation (3). In the case of Yb, YbF

3 could also be obtained. The reaction times and turnover rates are shown in

Table 2.

As well as the products of the reaction with the alkali metals, the dried products of the reaction between alkaline earth and rare earth metals with SF6, were sealed in borosilicate glass tubes for the crystallization at 450 °C over five days in a single zone tube furnace. In the case of Sr, Ba and Eu, the X-ray powder diffraction patterns show the bivalent fluorides MIIF2 and sulfides MIIS. Additionally, byproducts, such as unreacted metal (Ba), amide that converts to nitride during the crystallization process (EuN), or silicon from the glass tube, could be obtained in some reactions. For ytterbium, the trivalent fluoride YbF3 could be observed next to YbN as a byproduct after crystallization, which suggests the formation of Yb(NH)2 as an intermediate. In all cases, it was not possible to detect elemental sulfur and the addition of diluted HCl lead to the formation of H2S.

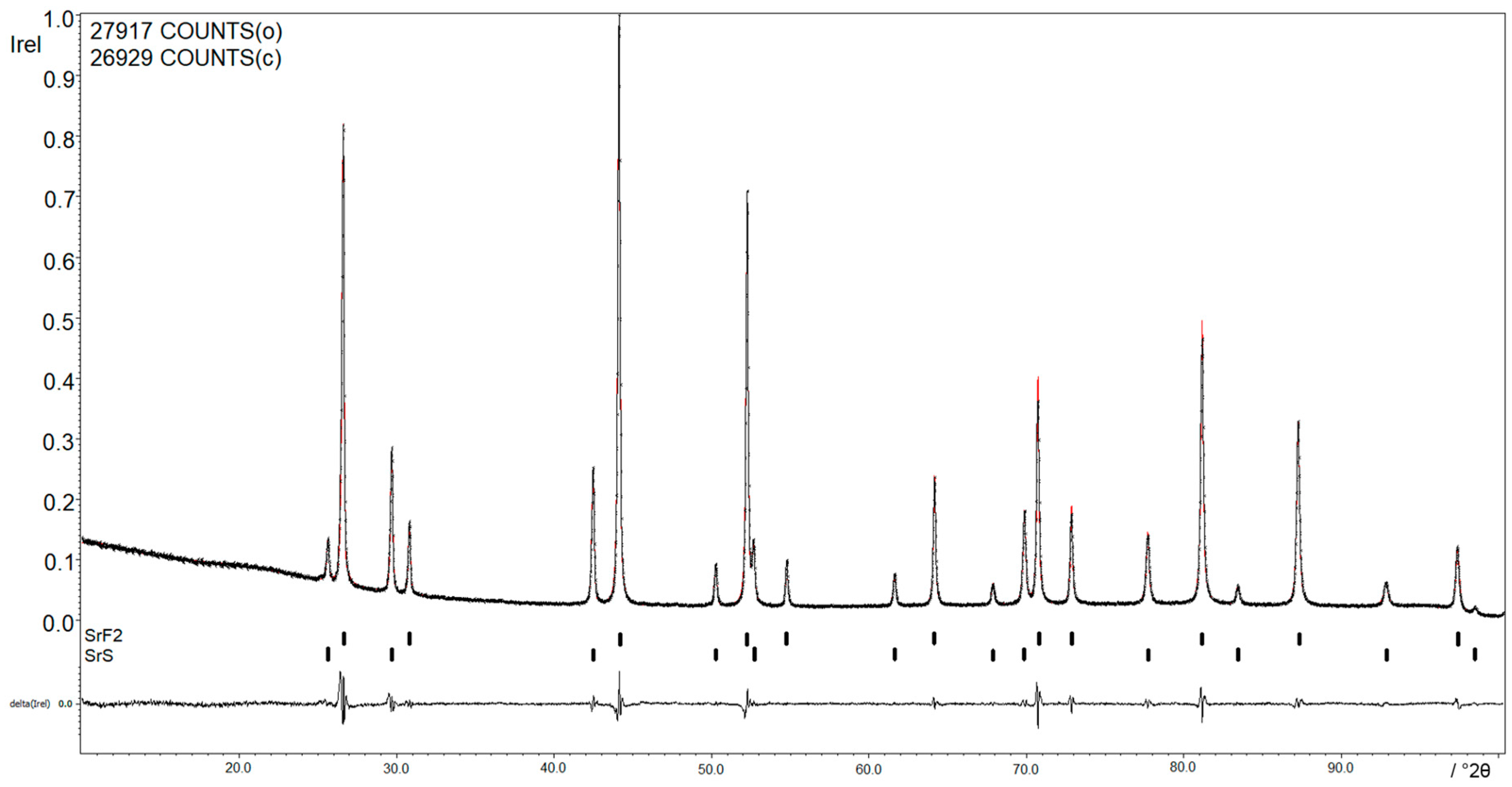

Figure 3 shows the X-ray powder diffraction pattern of the reaction between Sr and SF

6. The lattice parameters of

a = 5.8004(6) Å,

V = 195.156(3) Å

3 for SrF

2 and of

a = 6.0157(7) Å,

V = 217.642(3) Å

3 for SrS are in accordance with the results shown in the literature [

14,

15].

The ATR IR spectrum (

Figure S2) shows no bands in the range of 4000 to 400 cm

−1. An IR band of SrS should be observed at 185 cm

−1 and 280 cm

−1, so there is no IR activity expected in the measured region [

16]. The measured intensities between 2200 and 1900 cm

−1 are signals from the ATR diamond module (

Figure S2).

3. Conclusions

SF6 reacts readily at −50 °C with dissolved metals (Li–Cs, Sr, Ba, Eu) in liquid ammonia under normal pressure. The reaction leads to mono- or bivalent fluorides and sulfides (MIF, MI2S; MIIF2, MIIS) and, in some cases, byproducts like amides are formed. For Yb, the trivalent fluoride could also be obtained. The method described here represents an elegant and easy path for the decomposition of SF6, which can be realized for small and, conceivably, for industrial batch sizes. The reactions could offer an opportunity for an effective removal of the existing SF6-stocks.

4. Materials and Methods

All work was carried out excluding moisture and air in an atmosphere of dried and purified argon (5.0, Praxair, Düsseldorf, Germany) using high-vacuum glass lines and a glovebox (MBraun, Garching, Germany). Liquid ammonia (Gerling Holz & Co., 99.98%, Hamburg, Germany) was dried and stored over sodium (VWR, Germany) in a special high-vacuum glass line with a Hg pressure relief valve. Sulfur hexafluoride (Solvay, 99.9%, Hannover, Germany) was directly passed into the reaction vessel without any further treatment.

The alkali metals Li, Na, K (Merck, >99%, Darmstadt, Germany; Lab Chem Röttinger, >99%, Dinslaken, Germany; Merck 99%) and the alkali earth metals Sr and Ba (Onyxmet, 99%; Onyxmet 99.8%, Olsztyn, Poland) were used as supplied. Rb and Cs were distilled according to Hackspill in a borosilicate glass distillery, which was treated with hot aqua regia several times und flame-dried under vacuum before the distillation [

17]. Eu and Yb were extracted several times over a fritt with liquid ammonia in a special Schlenk vessel [

18]. All metals were stored in the glove box under argon in closed flasks.

All glass vessels were made of borosilicate glass, and were flame-dried several times under vacuum before use.

For the reactions, the Schlenk vessels were charged with an amount of metal shown in

Table 3. About 20–25 mL of the predried liquid ammonia was condensed at −78 °C (Isopropanol/CO

2-bath) onto the metal. An intense blue to metallic bronze color was obtained for the solution. Subsequently, because of the sublimation point of −63.8 °C for SF

6, the mixture was warmed to −50 °C by cooling the vessel with isopropanol and an Ultra-Low Refrigerated-Heating Circulator (Julabo FP 90, Seelbach, Germany). After 50–135 min, the blue colour of the solution disappeared and the liquid ammonia was removed slowly under vacuum.

4.1. Powder X-ray Diffraction

The powder X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded at room temperature with a STOE Stadi MP powder diffractometer (STOE, Darmstadt, Germany). The diffractometer used Cu Kα1 radiation, a Ge monochromator and a Mythen1K detector. The samples were powdered in a glovebox under argon atmosphere in agate mortars and sealed into borosilicate capillaries with a diameter of 0.3 mm, which were flame-dried several times under vacuum before utilization. All samples were charged in the glove box in a flame-dried ampoule (8 mm outer diameter, 1.5 mm wall thickness). A stopcock attached to the ground joint allowed transfer of the ampoule to a Schlenk line. The bottom of the ampoule was cooled with liquid nitrogen, and the ampoules were flame sealed under vacuum (1 × 10−3 mbar). These ampoules were annealed in a tube furnace for 5 days at 450 °C for better crystallization.

The evaluation of the powder X-ray patterns was carried out with the

WinXPOW software package and the ICDD powder diffraction file database [

19,

20]. Le Bail fitting and Rietveld refinement were done with JANA 2006 [

21].

4.2. IR Spectroscopy

The IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker alpha FT-IR-spectrometer (Bruker Optik GmbH, Rosenheim, Germany) using the ATR Diamond module with a resolution of 4 cm

−1. The spectrometer was located inside a glovebox under argon atmosphere. The spectra were processed with the

OPUS software package [

22].

4.3. SEM Imaging

The scanning electron microscopy images were recorded on a JEOL JIB 4610F (Jeol, Freising, Germany), dual beam FIB/SEM with a Schottky thermal files emission gun (acceleration voltage 0.2–30 kV, resolution 1.2 nm at 30 kV, 3.0 nm at 1 kV), a Gallion ion source (acceleration voltage 1–30 kV, resolution 5 nm at kV and a backscattered and secondary electron detector.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at

www.mdpi.com/2304-6740/5/4/68/s1, Figure S1: IR spectrum of RbF and Rb

2S measured on an ATR diamond module, Figure S2: IR spectrum of SrF

2 and SrS measured on an ATR diamond module.

Acknowledgments

Florian Kraus thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for a Heisenberg professorship. We thank Solvay for the donation of SF6 and Harms, Marburg, for the X-ray measurement time. For the SEM images we thank Michael Hellwig from the Center of material science of the Philipps-University Marburg.

Author Contributions

Holger Lars Deubner performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. Florian Kraus designed research and analyzed the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, 102nd ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 556–557. ISBN 3110177701. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, M.K.W.; Sze, N.D.; Wang, W.C.; Shia, G.; Goldman, A.; Murray, F.J.; Murcray, D.G.; Rinsland, C.G. Atmospheric sulfur hexafluoride: Sources, sinks and greenhouse warming. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 10499–10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, F.E.; Mani, E. Sulfur fluorides. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th ed.; Kroschwitz, J.I., Howe-Grant, B.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 428–442. [Google Scholar]

- Zámosta, L.; Braun, T.; Braun, B. S–F and S–C Activation of SF6 and SF5 Derivatives at Rhodium: Conversion of SF6 into H2S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2745–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holze, P.; Horn, B.; Limberg, C.; Matlachowski, C.; Mebs, S. Aktivierung von Schwefelhexafluorid an hoch reduzierten niedrig koordinierten Nickel-Distickstoff-Komplexen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2750–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, J.; Zhou, J.Z.; Xu, Z.P.; Li, Y.; Cao, T.; Zhao, J.; Ruan, X.; Liu, Q.; Qian, G. Decomposition of Potent Greenhouse Gas Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF6) by Kirchsteinite-dominant Stainless Steel Slag. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moissan, H.; Lebeau, P.C.R. Sur un nouveau corps gazeux: Le perfluorure de soufre SF6. Acad. Sci. Paris C. R. 1900, 130, 865–871. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen, H.C.; Riding, F.; Warhurst, E.J. The Reaction of Sulphur Hexafluoride with Sodium. Chem. Soc. 1953, 4168–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demitras, G.C.; MacDiarmid, A.G. The Low Temperature Reaction of Sulfur Hexafluoride with Solutions of Sodium. Inorg. Chem. 1964, 3, 1198–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewe, L.; Chang, C.; King, B. Sulfur Hexafluoride. Its reaction with Ammoniated Electrons and Its Use as a Matrix for Isolated Gold, Silver and Copper Atoms. Inorg. Chem. 1970, 9, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouillon, J.C.; Sebaoun, A. Le systéme eau-fluorine de rubidium. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1969, 36, 2604–2608. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria Pérez, D.; Vegas, A.; Muehle, C.; Jansen, M. High pressure experimental study on Rb2S: Antifluorit to Ni2In-type phase transitions. Acta Cryst. B 2011, 67, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sobdev, D.P.; Kaimov, D.N.; Sul’yanov, S.N.; Zhanorova, Z.J. Nanostructured crystals of fluorite phases Sr1 − xRxF2 + x (R are rare-earth elements) and their ordering. I. Crystal growth of Sr1 − xRxF2 + x (R = Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu). Crystallogr. Rep. 2009, 54, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Andreev, O.V.; Kartman, A.V.; Bamborov, V.G. Phase equilibria in the SrS–Ln2S3 systems (La = La, Nd, Gd). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 36, 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Koda, T. Optical Properties of Alkaline-Earth Chalcogenides, I Single Crystal Growth and Infrared Reflection Spectra Due to optical Phonons. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1982, 51, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackspill, L. Sur quelques propriétés des métaux alcalins. Helv. Chim. Acta 1928, 11, 1003–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassler, J.; Lagowski, J.J. The Chemistry of Non-Aqueous Solvents; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1966; Volume 1, p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- STOE WinXPOW, version 3.07; Stoe & Cie GmbH: Darmstadt, Germany, 2015.

- International Centre for Diffraction Data, PDF-2 2003 (Database); ICDD: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2003.

- Petricek, V.; Dusek, M.; Palatinus, L. Jana 2006–The Crystallographic Computing System; Institute of Physics: Praha, Czeck Republic, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OPUS, version 7.2; Bruker Optik GmbH: Ettlingen, Germany, 2012.

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).