1. Introduction

Under the dual pressures of energy shortage and environmental pollution today, thermoelectric materials, as a type of functional material that can directly convert thermal energy into electrical energy, are receiving increasing attention [

1,

2,

3]. Based on the Seebeck effect [

4] and the Peltier effect [

5], thermoelectric materials can directly convert medium and low-temperature waste heat used in Aiye Processing Equipment, such as industrial waste heat and automobile exhaust waste heat, into electrical energy, effectively improving energy utilization efficiency and reducing dependence on traditional fossil fuels [

6,

7,

8]. At the same time, thermoelectric refrigerators made using the Peltier effect have the advantages of small size, light weight, no mechanical moving parts, no noise, and no liquid or gaseous media, causing no pollution to the environment and being able to achieve precise temperature control. In addition, thermoelectric materials also have important applications in the aerospace field. For example, radioisotope thermoelectric generators provide a reliable power source for deep-space probes. Compared with traditional energy conversion technologies, thermoelectric materials have unique advantages such as no moving parts, high reliability, and low maintenance costs, providing a new way to solve energy and environmental problems and showing broad application prospects in many fields such as energy, electronics, and aerospace [

9,

10].

Oxide thermoelectric materials show diverse application potential due to their unique advantages [

11,

12]. Their excellent high-temperature stability and chemical inertness make them suitable for industrial waste heat recovery scenarios, which can directly convert medium and high-temperature waste heat emitted from iron and steel, chemical and other fields into electrical energy, reducing energy waste [

13,

14,

15]. The practical application of modern oxide thermoeletric materials is still limited by their characteristics and production technology. The key indicator of their thermoelectric performance, the dimensionless figure of merit ZT, is generally low [

16,

17]. The fundamental challenge stems from the strong coupling between the Seebeck coefficient, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity. For instance, enhancing electrical conductivity often compromises the Seebeck coefficient, while strategies to lower thermal conductivity can disrupt electron transport pathways. This interdependence makes the simultaneous optimization of all three parameters exceedingly difficult. As an important branch of oxide thermoelectric materials, indium oxide has significant characteristic advantages [

18,

19]. It is inherently an n-type semiconductor with a regular electron transport channel, and there are adjustable lattice gaps in its crystal structure, which provides a structural basis for optimizing thermoelectric performance through doping and defect engineering. Compared with traditional thermoelectric materials containing toxic elements such as lead and tellurium, indium oxide is non-toxic and has good environmental compatibility, conforming to the development trend of green materials. In addition, indium oxide has good chemical stability in the medium and low-temperature range, and is not prone to oxidation or phase change due to temperature fluctuations, making it suitable for more civil and industrial medium and low-temperature thermoelectric scenarios. The thermoelectric performance of pure indium oxide still has obvious shortcomings. Its intrinsic electrical conductivity is low, and electrons are easily affected by atomic scattering during transmission in the lattice, resulting in limited carrier mobility. At the same time, the lattice thermal conductivity of pure indium oxide is relatively high, and a large amount of thermal energy is transferred through lattice vibration, which cannot be effectively converted into electrical energy, ultimately making it difficult to improve the ZT value. In addition, indium oxide is relatively brittle, and cracks can easily form during the cutting and packaging processes of thermoelectric devices, adversely affecting their long-term service reliability. Previous studies have attempted to enhance performance through methods such as Mo doping [

17], Al doping [

14], and Bi doping [

15], achieving promising results.

Unlike traditional high-valence dopants, the trivalent rare-earth ion lanthanum (La

3+) exhibits a unique mode of interaction with the indium oxide (In

2O

3) lattice. When La

3+ substitutes for In

3+, it does not directly generate extra free electrons; instead, it induces the formation of oxygen vacancies to maintain charge neutrality. Notably, the identical stoichiometry of In

2O

3 and La

2O

3 makes the formation of these oxygen vacancies not readily explainable through simple compositional matching. These oxygen vacancies act as effective donors, releasing free electrons into the lattice to enhance electrical conductivity. This unique “La substitution-oxygen vacancy-electron injection” mechanism avoids the risk of excessive carrier concentration that often plagues high-valence doping. It enables gentle and precise tuning of carrier density, ensuring the material maintains a balanced relationship between electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient—two core parameters for optimizing thermoelectric power factor. La doping introduces dual innovations to reduce lattice thermal conductivity. First, the larger ionic radius of La

3+ compared to In

3+ causes moderate lattice distortion in the In

2O

3 structure. This distortion disrupts the regular transmission path of phonons (the main carriers of heat), enhancing scattering of medium-frequency phonons. Second, La’s unique 4f electron configuration creates local electric field perturbations in the lattice. These perturbations specifically target low-frequency phonons—an energy range that conventional defects struggle to scatter—further weakening heat transfer. This synergistic effect of lattice distortion and electric field perturbation represents an innovative approach to thermal transport, distinct from the single defect mechanism of traditional dopants. La’s strong chemical affinity for oxygen and inherent thermal stability bring key advantages to In

2O

3. After doping, La forms stable La-O-In bond networks within the In

2O

3 lattice, which inhibit oxygen desorption and lattice rearrangement at high temperatures. This prevents performance degradation caused by structural collapse or compositional changes—common issues in traditional oxide thermoelectrics like ZnO-based materials—even in long-term high-temperature air environments [

18,

19]. Additionally, La’s 4f electrons improve the material’s resistance to humidity and chemical corrosion, expanding its applicability beyond ideal lab conditions to harsh industrial scenarios such as waste heat recovery from flue gases or chemical reactors.

2. The Results and Discussions

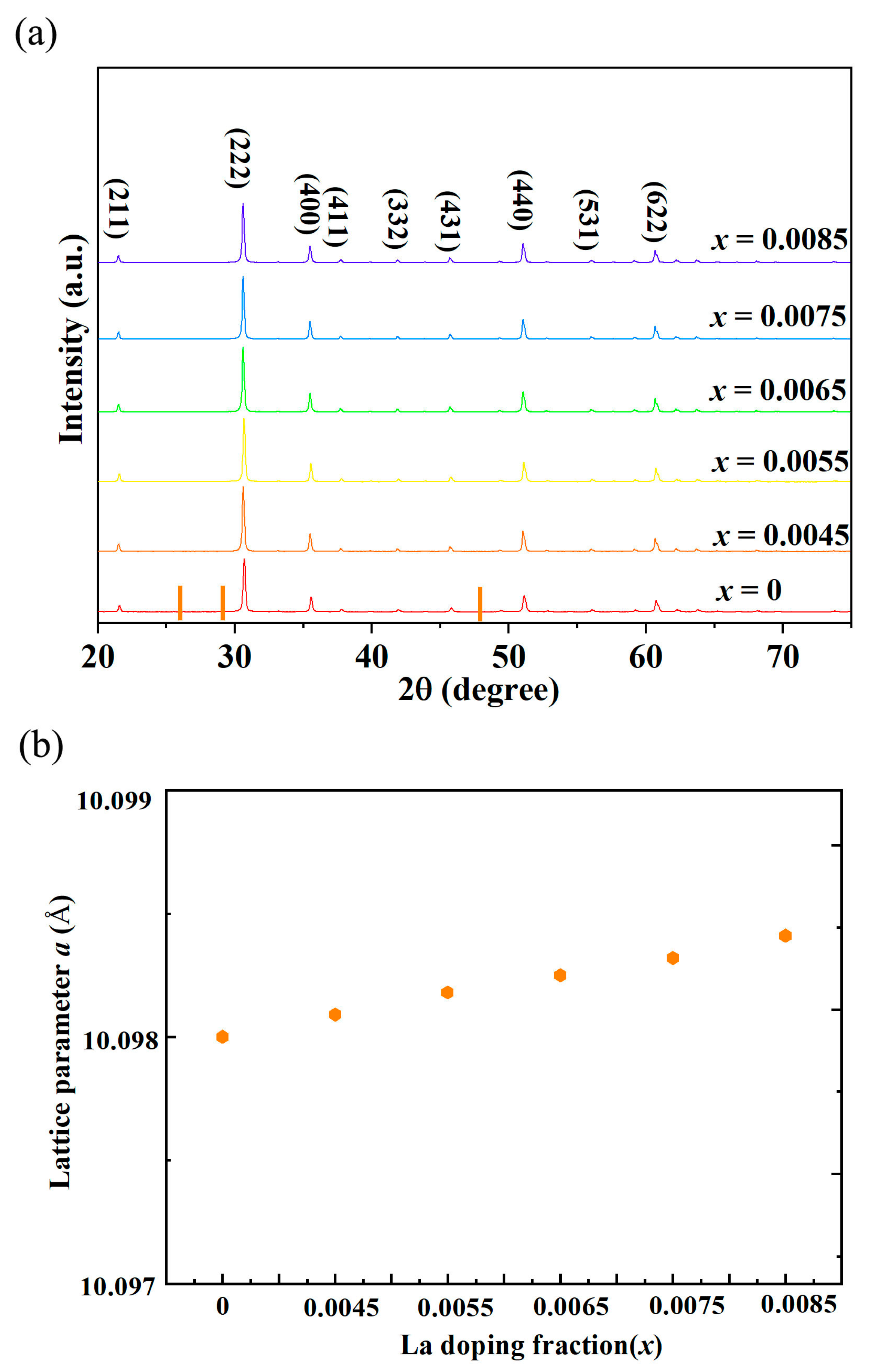

Figure 1 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of La-doped indium oxide (In

2O

3). The diffraction pattern shows only the characteristic peaks corresponding to the cubic bixbyite structure of pure In

2O

3. No extra peaks attributable to secondary phases, such as lanthanum oxide (La

2O

3) or other La-In-O compounds, are detected within the instrument’s detection limits. The increased lattice constants as shown in

Table 1 indicate the overall expansion of the lattice constant in the La-doped sample compared to the pure In

2O

3. The combination of these two observations—phase purity and lattice expansion—strongly suggests that the primary mechanism for La incorporation into the In

2O

3 structure is substitutional doping. This means La atoms have replaced In atoms at their regular crystallographic sites within the lattice. The underlying reason for the lattice expansion lies in the difference in ionic radii between the host cation (In

3+) and the dopant cation (La

3+) [

20,

21]. The ionic radius of In

3+ in a six-fold coordination (which is the common coordination in the bixbyite structure) is approximately 0.80 Å. The ionic radius of La

3+ in a six-fold coordination is approximately 1.032 Å. There is a significant size mismatch, with La

3+ being about 29% larger than In

3+. When these larger La

3+ ions replace the smaller In

3+ ions at the center of the coordination polyhedra, they push the surrounding oxygen ions outward. This local “pushing” effect, when replicated throughout the entire crystal lattice, results in a uniform expansion of the unit cell in all three dimensions, thereby increasing the overall lattice constant.

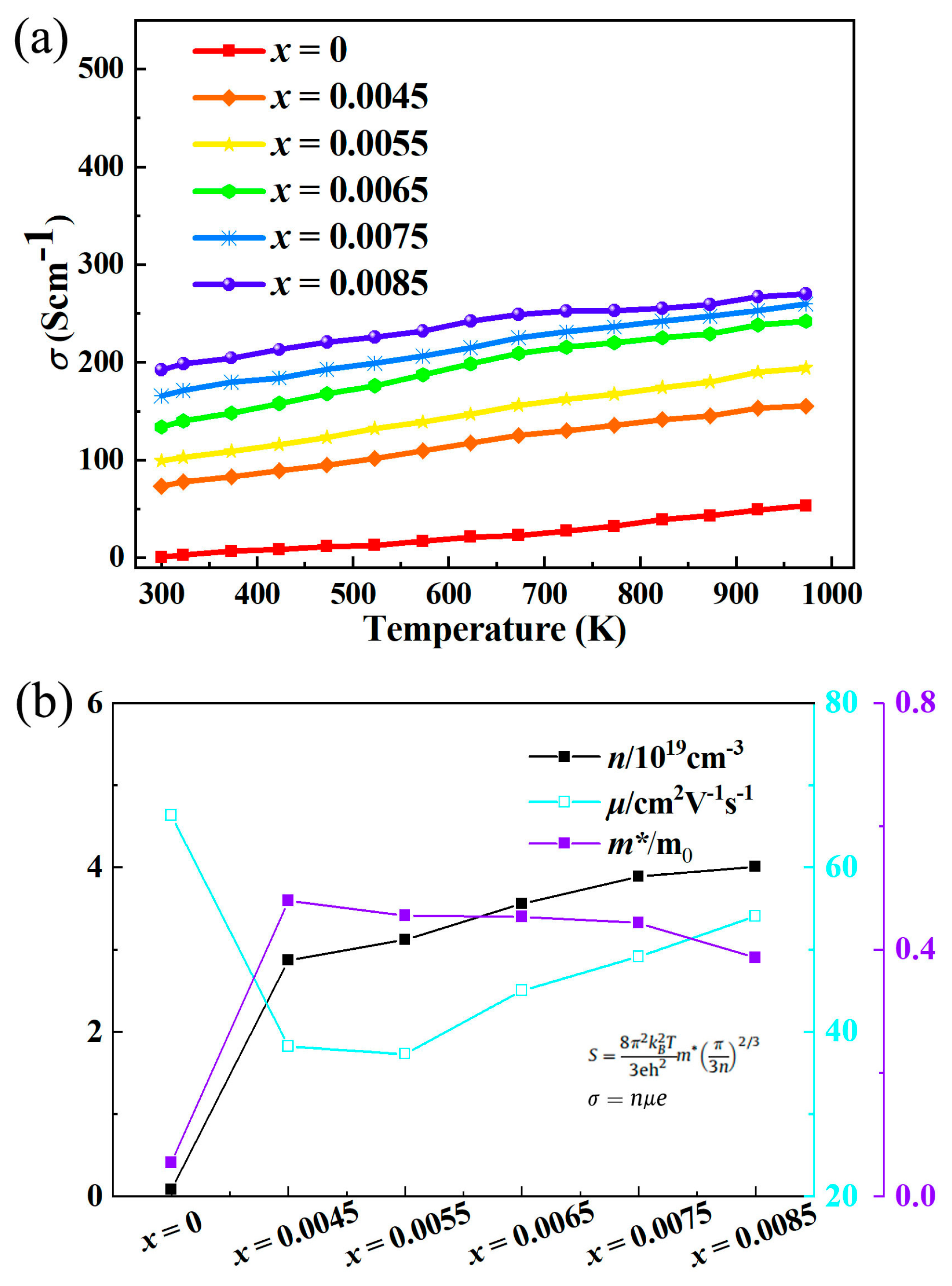

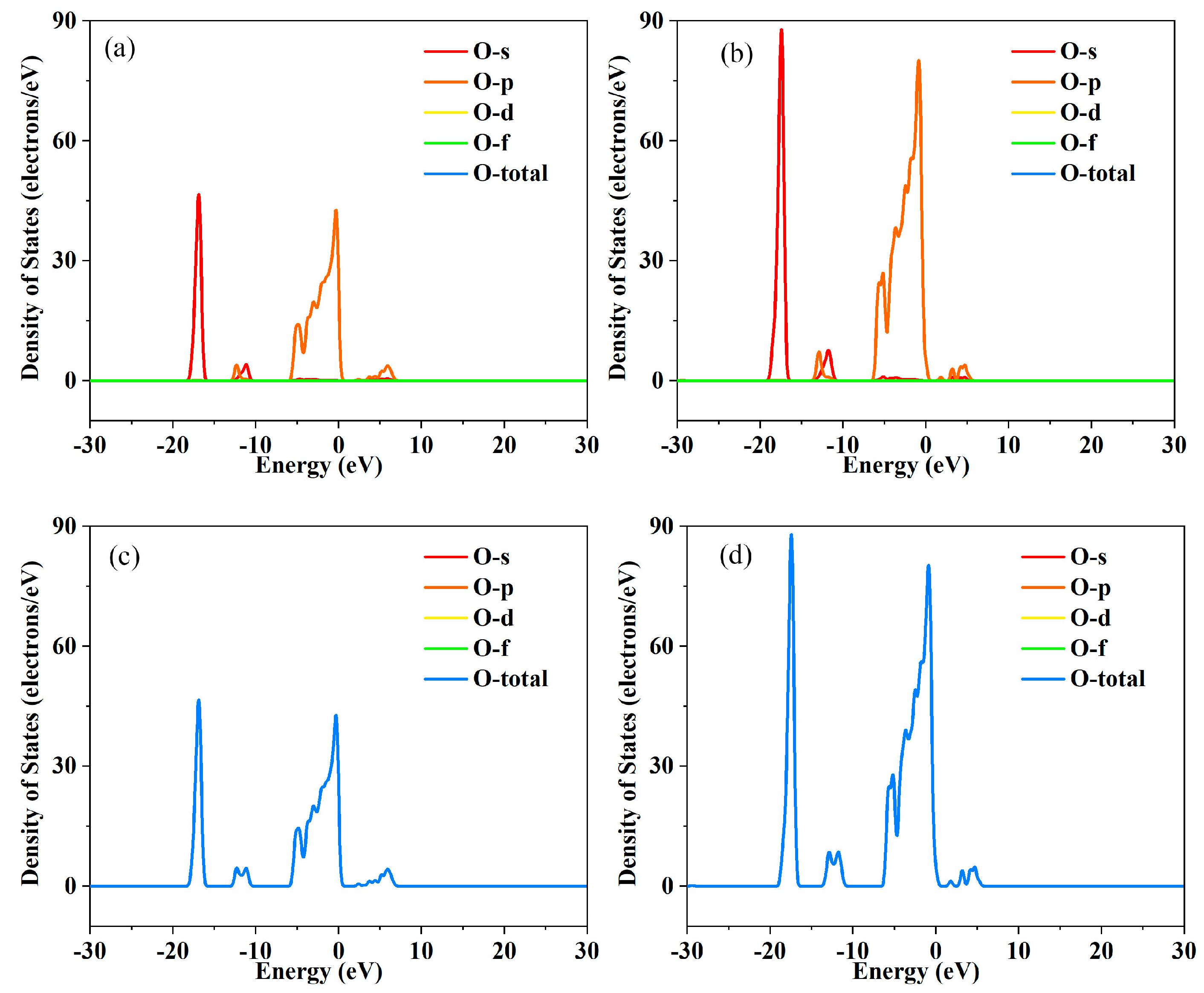

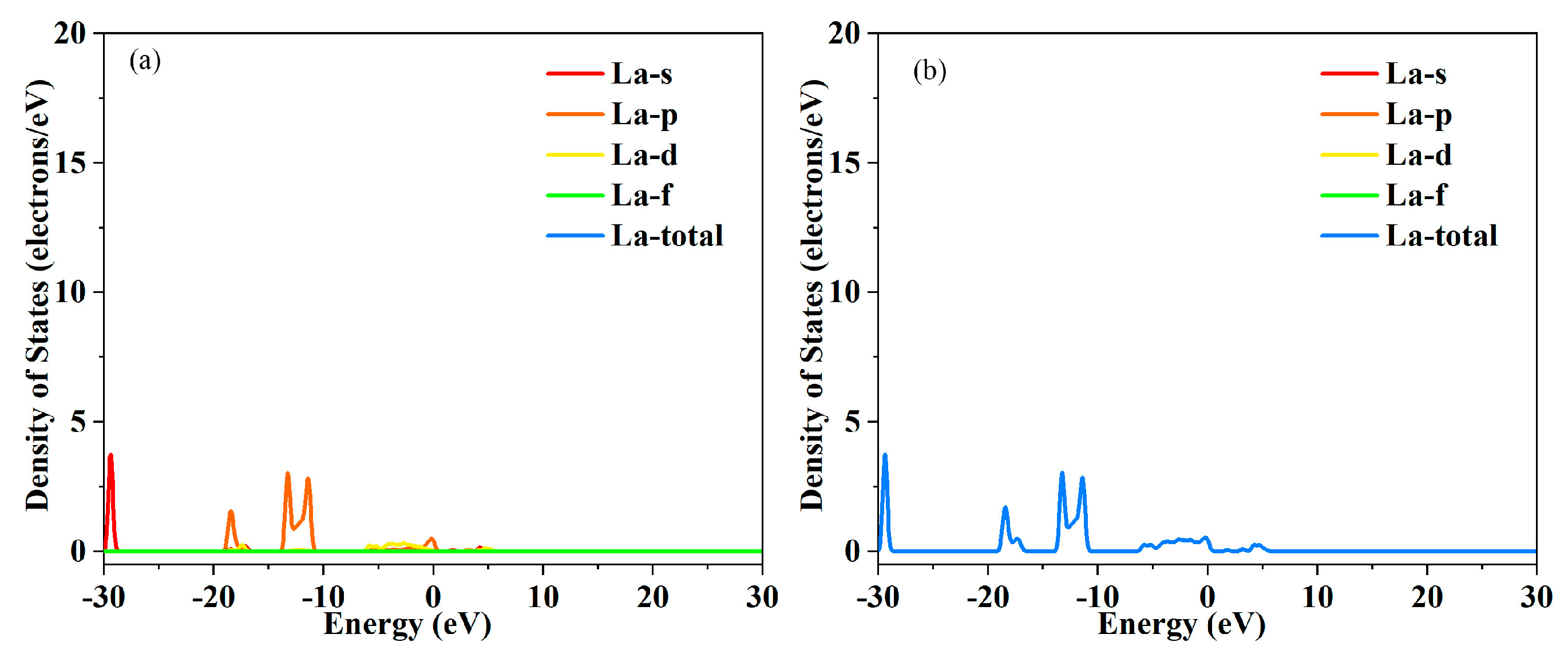

The most direct factor responsible for the enhanced electrical conductivity of La-doped In

2O

3 is the significant improvement of carrier concentration as shown in

Figure 2. In

2O

3 has a cubic bixbyite structure, where indium atoms primarily exist in the +3 oxidation state, and the intrinsic carrier concentration is governed by native defects such as oxygen vacancies. When La

3+ ions are doped into the In

2O

3 lattice, they tend to occupy the lattice sites of In

3+ due to the similar ionic radius (La

3+ ionic radius is 1.03 Å, In

3+ ionic radius is 0.80 Å). However, the valence state matching between La

3+ and In

3+ seems to not directly generate additional carriers, but the doping process induces the formation of a large number of oxygen vacancies to maintain the charge neutrality of the system. Oxygen vacancies in In

2O

3 are typical donor defects, which can release free electrons into the conduction band. The formation energy of oxygen vacancies decreases significantly after La doping, which promotes the spontaneous generation of oxygen vacancies during the material preparation process. Each oxygen vacancy can provide two free electrons, leading to a sharp increase in the electron concentration of the system [

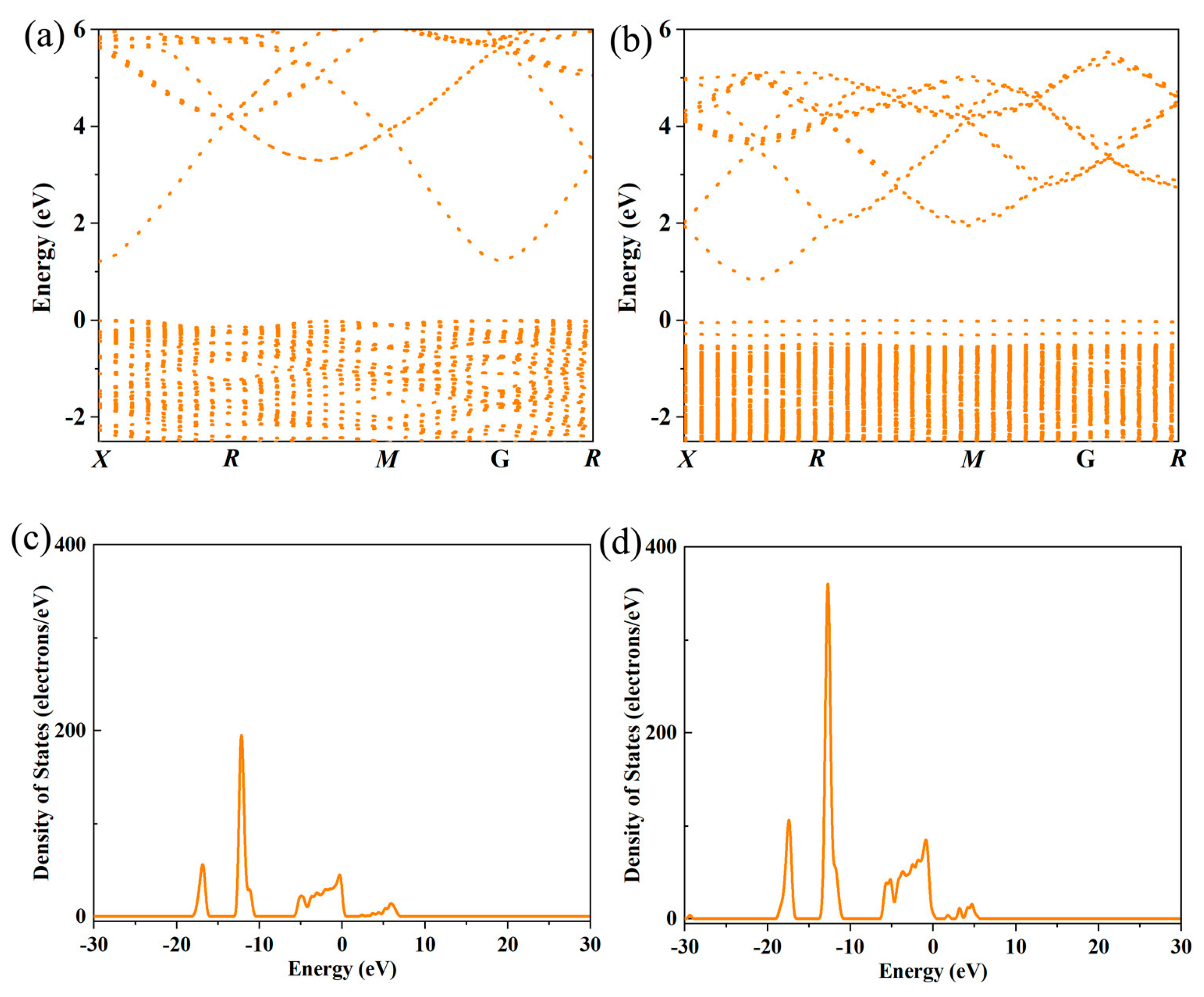

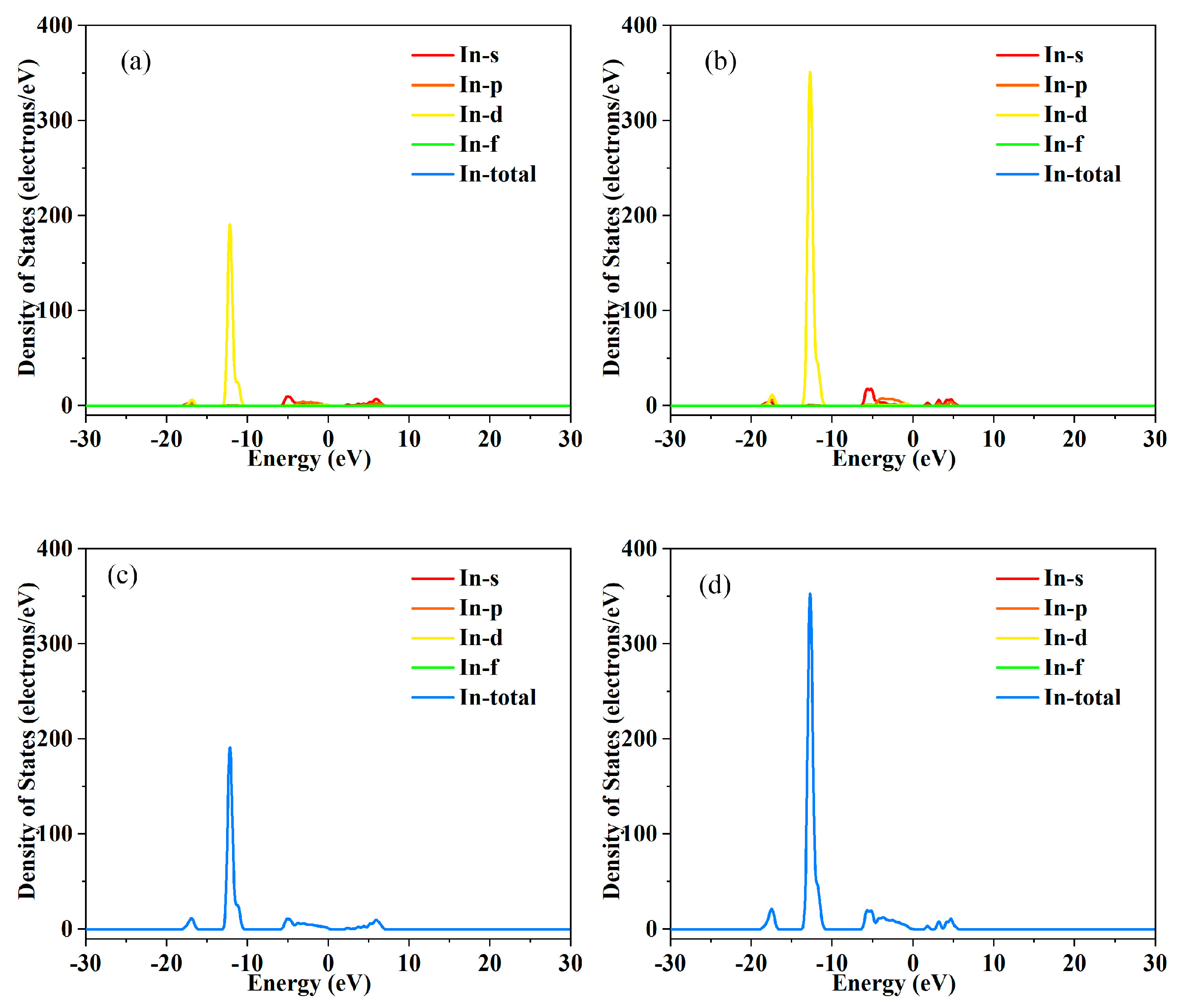

18]. Experimental data show that with the increase of La doping content (within the solid solubility range), the carrier concentration increases linearly, which is consistent with the variation trend of oxygen vacancy concentration. This significant increase in carrier concentration directly makes up for the negative impact of the slight decrease in mobility on electrical conductivity, becoming the dominant factor driving the increase in electrical conductivity. The electronic structure of La-doped In

2O

3 was calculated using the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) exchange-correlation functional based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) via the CASTEP module in Materials Studio. From a theoretical perspective, the GGA functional has an inherent limitation of systematically underestimating the band gap value when describing the electronic band structure of semiconductors and insulators. The core reason is that the ground-state energy functional of DFT cannot accurately describe the behavior of excited electrons near the conduction band minimum, leading to the underestimation of the conduction band minimum energy. Consequently, the calculated band gap is smaller than the experimentally measured value. For wide-band-gap semiconductors such as In

2O

3, the band gap value calculated by the GGA functional is usually only 1/3–1/2 of the experimental value. This deviation is a well-recognized common issue of this calculation method in academia. Although the calculated band gap value (1.12 eV) in this study is lower than the experimentally measured value of In

2O

3 (~3 eV), the calculation results still have important physical significance. The calculation results can accurately reflect the regulatory effect of La doping on the band structure of In

2O

3, such as the variation trend of the band gap after doping, the introduction position of impurity energy levels, and the dispersion characteristics of the valence band and conduction band. In addition, the increase in the density of states near the Fermi level caused by band convergence further enhances the contribution of carrier concentration to electrical conductivity. The convergence of multiple energy bands near the Fermi level makes more electronic states available for carrier occupation, which not only increases the number of effective carriers participating in conduction but also enhances the delocalization of electrons. This delocalization effect enables electrons to be more easily excited from the valence band to the conduction band, further increasing the actual carrier concentration involved in electrical transport. While La doping increases the carrier concentration, it causes a slight decrease in carrier mobility, but this decrease does not reverse the overall upward trend of electrical conductivity. The change in carrier mobility is mainly related to the scattering mechanism inside the material. After La doping, the lattice distortion of In

2O

3 increases. Due to the difference in ionic radius between La

3+ and In

3+, the introduction of La ions destroys the periodicity of the original lattice, leading to lattice defects such as lattice distortion and strain. These defects act as scattering centers for carriers, increasing the probability of carrier-lattice scattering during the transport process, thereby reducing the carrier mobility. In addition, the increase in carrier concentration also leads to an enhancement of carrier-carrier scattering. With the increase of free electron concentration, the interaction between electrons becomes more intense, which increases the collision probability between carriers. This carrier-carrier scattering further inhibits the movement of carriers, resulting in a decrease in mobility. However, the degree of mobility reduction is relatively mild, which is mainly due to the band convergence effect. Band convergence optimizes the electronic band structure of In

2O

3, making the band effective mass of carriers decrease. According to the relationship between mobility and effective mass (μ ∝ 1/m*, where m* is the effective mass of carriers), the decrease in effective mass helps to offset the scattering-induced mobility reduction. Therefore, the mobility of La-doped In

2O

3 only decreases slightly, and its negative impact on electrical conductivity is far less than the positive contribution of the significant increase in carrier concentration. The band convergence phenomenon after La doping is another key factor affecting the electrical conductivity of In

2O

3. The intrinsic band structure of In

2O

3 has multiple discrete energy bands, and only a small number of energy bands near the Fermi level participate in electronic transport. After La doping, the introduction of La 4f orbitals interacts with In 5s and 5p orbitals, adjusting the energy level positions of the original bands as shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. This interaction leads to the convergence of multiple energy bands near the Fermi level, forming a broader and more continuous energy band region. Band convergence directly increases the density of states near the Fermi level. A higher density of states means that there are more electronic states available for occupation at the same energy level, which not only promotes the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band but also enhances the carrier concentration. At the same time, the continuous energy band formed by convergence reduces the energy barrier for carrier transport. Carriers can move more smoothly between different energy bands, reducing the scattering probability during the transport process to a certain extent. The bandgap values obtained through first-principles calculations are as follows: ~1.12 eV for the undoped, ~0.86 eV for La doped. After doping with La, the density of electronic states at the bottom of the conduction band is significantly enhanced, and the energy required for valence band-conduction band transitions decreases, manifesting macroscopically as a contraction of the optical bandgap. The hybridization between La’s 4f orbitals and In’s 5s, 5p orbitals, as well as O’s 2p orbitals, forms new impurity energy levels in the forbidden band. These energy levels serve as an “intermediate bridge” for electronic transitions, effectively reducing the effective bandgap. For the maintenance of lattice charge neutrality, the key lies in the synergistic effect of ion valence adjustment and defect compensation. Specifically, when La

3+ ions substitute for In

3+ ions at the indium lattice sites, the formation of oxygen vacancies leads to the emergence of positively charged oxygen vacancies. To balance these excess positive charges, a portion of In

3+ ions in the lattice may be reduced to In

2+ ions with lower valence states. The decrease in the valence of partial indium ions provides sufficient negative charge compensation to offset the positive charges from oxygen vacancies. In addition, the band convergence optimizes the electronic structure of the material, improves the delocalization of electrons, and enhances the conductivity of the electronic system. This comprehensive effect of band convergence further promotes the improvement of electrical conductivity while increasing the carrier concentration.

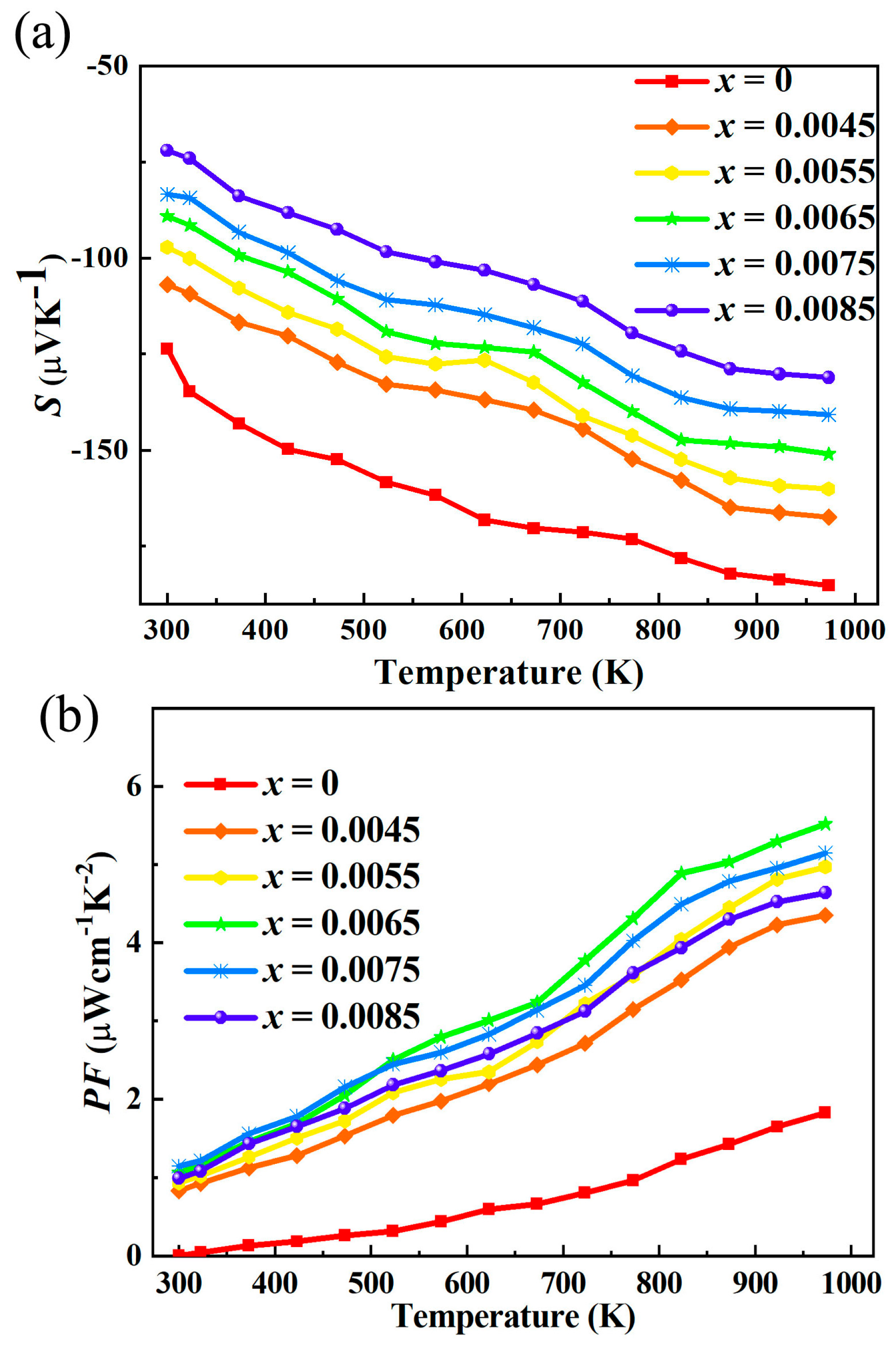

After La doping, the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient of indium oxide thermoelectric materials decreases significantly as shown in

Figure 7, which is essentially the result of the synergistic effect of changes in carrier concentration, electrical conductivity, and carrier mobility. First, carrier concentration increase is the core factor leading to the decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient. Pure indium oxide is a wide-bandgap semiconductor with relatively low intrinsic carrier concentration. When La

3+ (trivalent) is doped into the indium oxide lattice to replace In

3+ (trivalent), though the valence state is the same, La doping introduces additional free electrons due to lattice distortion and defect formation (e.g., oxygen vacancies induced by charge compensation). According to the Mott formula, the Seebeck coefficient (S) is inversely related to the logarithm of carrier concentration (n), i.e., S ∝ ln(1/n). As n increases, the probability of carriers (electrons) transitioning between energy levels near the Fermi level rises, reducing the energy difference that carriers need to absorb/release to move, thus lowering the absolute value of S. Second, electrical conductivity enhancement is closely associated with the change in Seebeck coefficient. Electrical conductivity (σ) follows the formula σ = neμ (where e is the electron charge, μ is carrier mobility). The increase in carrier concentration (n) directly contributes to higher σ. In thermoelectric materials, there is a trade-off between Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity: higher σ usually corresponds to lower |S|. This is because a higher number of carriers means more charge carriers participate in current transport, but each carrier carries less net energy (since the energy distribution of carriers becomes more uniform), weakening the thermoelectric potential difference (the physical origin of the Seebeck effect) and further reducing |S|. Third, carrier mobility reduction has a minor regulatory effect on the Seebeck coefficient. La ions have a larger ionic radius than In ions. After doping, La

3+ entering the In

2O

3 lattice causes severe lattice distortion, and the formed lattice defects (e.g., La-In antisite defects, oxygen vacancies) act as scattering centers for carriers. This scattering increases the collision probability of electrons during transport, leading to a decrease in carrier mobility (μ). Theoretically, lower μ would slightly increase |S| by reducing the number of high-energy carriers. However, in La-doped indium oxide, the increase in carrier concentration is much more significant than the decrease in mobility. Therefore, the dominant effect of n increase overwhelms the weak regulatory effect of μ decrease, resulting in an overall reduction in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient.

For La-doped indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials, the observed increase in power factor with the highest value of 5.52 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K), accompanied by a decreased absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient, enhanced electrical conductivity, elevated carrier concentration, reduced mobility, band convergence, and increased density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level, stems from the synergistic regulation of electronic structure and carrier transport properties by La doping. The power factor is determined by the combined effect of the Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity, with a strong dependence on their synergy. After La doping, the significant increase in electrical conductivity (driven by elevated carrier concentration) compensates for the loss caused by the decreased absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient. Although La doping causes a slight decrease in carrier mobility—due to lattice distortion from the ionic radius difference between La3+ and In3+, which increases phonon scattering and ionized impurity scattering of carriers—the substantial increase in carrier concentration far outweighs the negative impact of reduced mobility. Thus, the overall electrical conductivity of the material is significantly enhanced after doping. The Seebeck coefficient is closely related to the DOS near the Fermi level and carrier concentration. For degenerate semiconductors like In2O3, the Seebeck coefficient follows the Mott formula, which is inversely proportional to the logarithm of carrier concentration. The increase in carrier concentration after La doping shifts the Fermi level into the conduction band, reducing the relative energy difference between carriers and the Fermi level, thereby decreasing the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient. However, the band convergence effect induced by La doping mitigates the degree of reduction in the Seebeck coefficient. La doping regulates the band structure of In2O3, making multiple adjacent conduction bands converge near the Fermi level. This convergence increases the DOS near the Fermi level, which is beneficial for maintaining a moderate Seebeck coefficient. The synergistic effect of increased carrier concentration and elevated DOS results in a controlled decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient, rather than a drastic drop. However, the band convergence effect induced by La doping mitigates the degree of reduction in the Seebeck coefficient. La doping regulates the band structure of In2O3, making multiple adjacent conduction bands converge near the Fermi level. This convergence increases the DOS near the Fermi level, which is beneficial for maintaining a moderate Seebeck coefficient. The synergistic effect of increased carrier concentration and elevated DOS results in a controlled decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient, rather than a drastic drop. The band convergence and increased DOS near the Fermi level play a key role in this synergy. The elevated DOS enhances the contribution of each carrier to the Seebeck coefficient, preventing an excessive drop in S2. Meanwhile, the improved electrical conductivity (from higher carrier concentration) directly boosts the overall power factor. This synergistic regulation—where carrier concentration dominates conductivity enhancement, and band structure optimization mitigates Seebeck coefficient reduction—ultimately leads to a significant improvement in the power factor of La-doped In2O3.

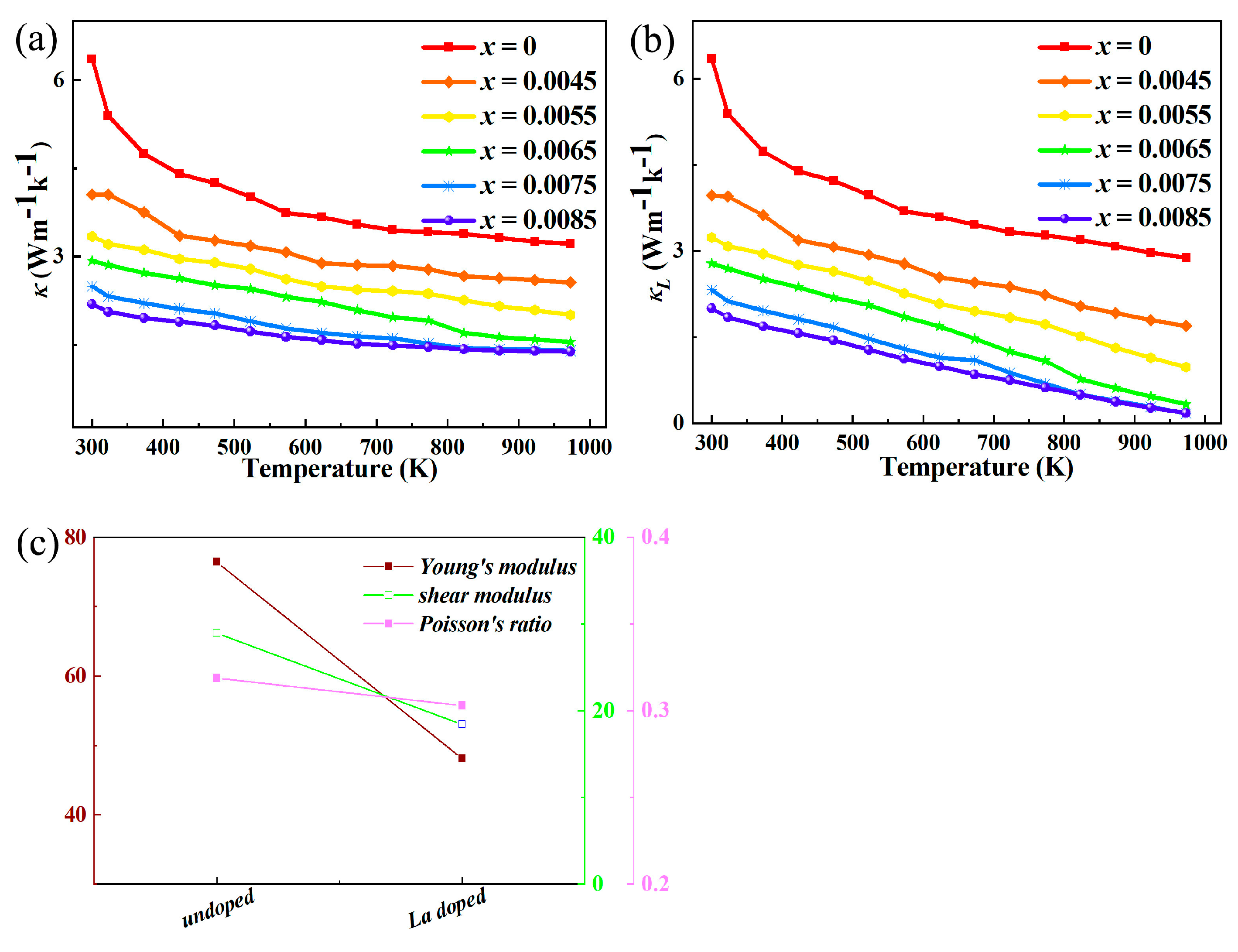

After La doping in indium oxide (In

2O

3), both the total thermal conductivity (κ) and the lattice thermal conductivity (κ

L) decrease as shown in

Figure 8. This can be attributed to several factors related to the introduction of La atoms into the In

2O

3 crystal structure. The primary reason for the decrease in lattice thermal conductivity is the enhanced scattering of phonons (lattice vibrations), which are the main carriers of heat in the lattice. La

3+ ions have a different ionic radius and mass compared to the In

3+ ions they replace. The significant mass difference between La and In atoms creates mass fluctuation fields within the crystal lattice. When phonons travel through the lattice, they are strongly scattered by these point defects (the La dopants), impeding the efficient propagation of heat and thus reducing κ

L. The difference in ionic radii between the dopant (La

3+) and the host cation (In

3+) creates local strain fields in the crystal structure. These strain fields act as additional scattering centers for phonons, further reducing the lattice thermal conductivity. The disorder caused by the random distribution of La and In atoms leads to alloy scattering of phonons. The reduction in lattice thermal conductivity (κ

L) is often the dominant factor in the decrease of the total thermal conductivity (κ) for these materials, especially if the electronic contribution (κ

e) does not increase drastically enough to offset the drop in κ

L. The observed changes in electrical properties are interconnected and stem from the fundamental action of La doping. La doping introduces point defects and mass disorder into the indium oxide lattice. Since La atoms have different atomic masses and radii compared to In atoms, they act as scattering centers for phonons. This intensifies phonon scattering, reducing the mean free path of phonons and thereby decreasing lattice thermal conductivity. The resultant mass contrast and strain fields significantly impede phonon propagation, contributing to the decline in lattice thermal conductivity. In La-doped In

2O

3, La

3+ (with a larger ionic radius) replaces In

3+, causing lattice distortion and weakening the original In-O chemical bonds. This bond weakening directly leads to a decrease in Young’s modulus. Meanwhile, Young’s modulus is closely related to phonon velocity (v). The reduction in E directly lowers the phonon propagation velocity in the lattice, laying the foundation for reduced lattice thermal conductivity. Young’s modulus reflects the stiffness of a material and the strength of interatomic bonding within the lattice. A higher Young’s modulus indicates stronger interatomic forces and a more rigid lattice structure, while a lower value signifies weaker interatomic bonding and increased lattice flexibility. A lower Young’s modulus increases lattice flexibility, making the lattice more prone to thermal vibrations (phonon–phonon scattering). This intensifies the umklapp scattering process between phonons, which is the main mechanism for limiting l

ph. Additionally, the lattice distortion caused by La doping introduces defects (e.g., substitutional atoms, lattice vacancies), and the reduced Young’s modulus enhances the interaction between these defects and phonons. The combined effect of stronger phonon–phonon scattering and defect–phonon scattering significantly shortens the phonon mean free path, further reducing κ

L. In La-doped In

2O

3, the weakened interatomic bonding (reflected by lower E) not only reduces Young’s modulus but also creates a more disordered lattice environment. This disorder synergistically amplifies phonon scattering and reduces phonon velocity, leading to a significant drop in κ

l. Since κ

l dominates total thermal conductivity in oxide thermoelectrics, the reduction in κ

l directly causes a decrease in total thermal conductivity. Thus, the decline in Young’s modulus acts as a bridge between structural distortion (from La doping) and thermal conductivity reduction, providing a critical mechanism for optimizing the thermoelectric performance of In

2O

3-based materials.

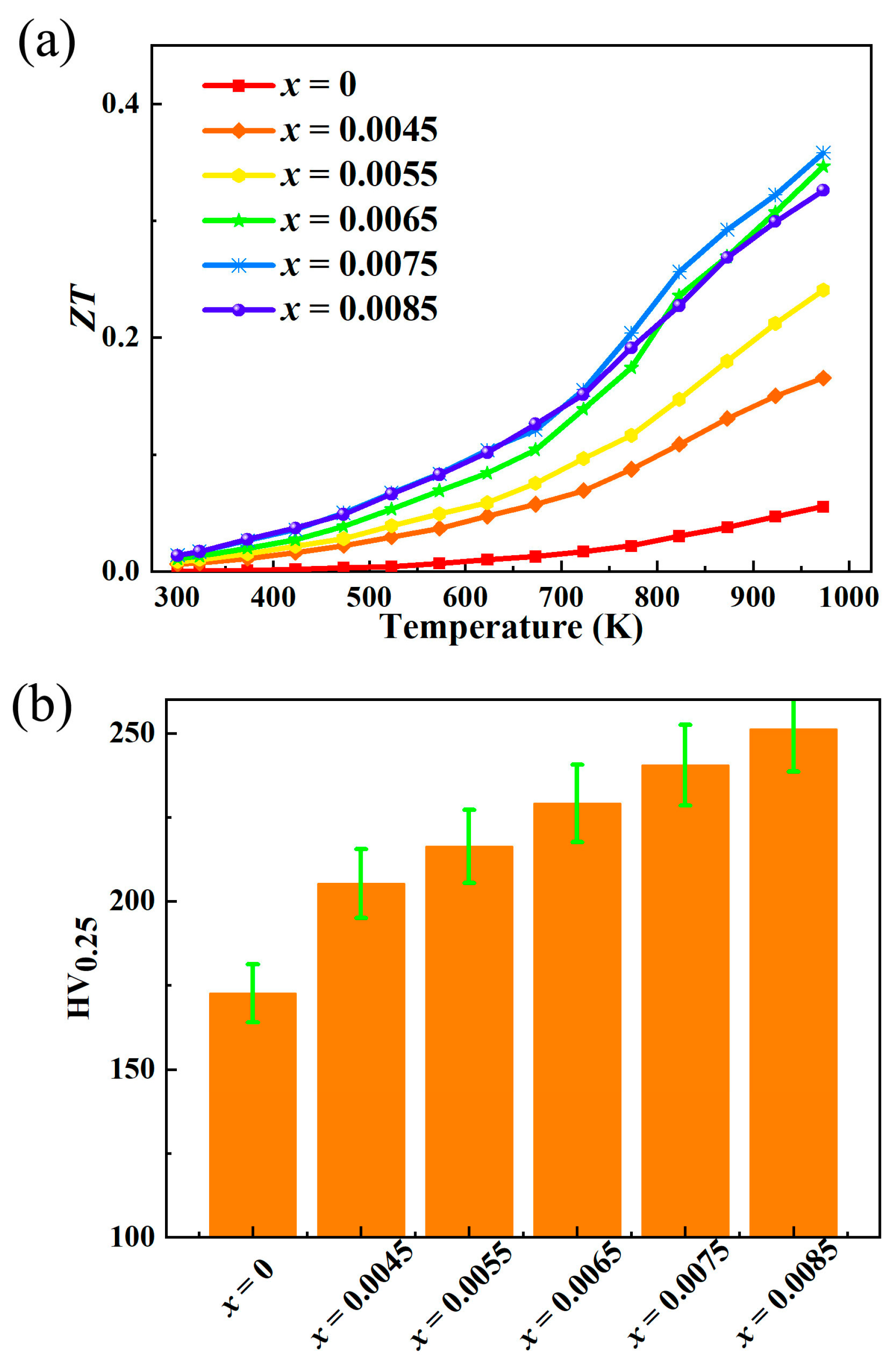

For La-doped indium oxide (In

2O

3) thermoelectric materials, the significant increase in ZT value as shown in

Figure 9a—from 0.055 to 0.358—stems from the synergistic optimization of electrical transport properties (enhanced power factor) and thermal transport properties (reduced total thermal conductivity and lattice thermal conductivity) by La doping. The highest ZT value reached 0.358, which is lower than 0.402 for Bi doping [

15], 0.42 for V doping [

22], and higher than 0.145 for Al doping [

14]. The power factor (PF = S

2σ) directly determines the electrical energy conversion capacity of thermoelectric materials, and its enhancement is a key driver of ZT value improvement. La doping optimizes the electrical transport properties of In

2O

3 through dual regulation of carrier concentration and electronic structure. La

3+ replaces In

3+ in the In

2O

3 lattice, and the charge compensation effect introduces a large number of free conduction electrons, significantly increasing the carrier concentration. Although the increase in carrier concentration leads to a moderate decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient (following the Mott formula for degenerate semiconductors), the substantial enhancement in electrical conductivity (σ = neμ, where n is carrier concentration, e is elementary charge, and μ is carrier mobility) far outweighs the loss caused by the reduced Seebeck coefficient. Meanwhile, La doping induces band convergence, increasing the density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level. This elevated DOS enhances the contribution of each carrier to the Seebeck coefficient, preventing an excessive drop in S

2. The synergistic effect of increased electrical conductivity and controlled Seebeck coefficient reduction results in a significant enhancement of the power factor, directly boosting the numerator of the ZT formula and laying the foundation for ZT value improvement. La doping causes lattice distortion: the ionic radius of La

3+ is larger than that of In

3+, leading to local lattice expansion and strain after substitution. This distortion increases phonon scattering—including phonon–phonon umklapp scattering and defect–phonon scattering—shortening the phonon mean free path. Additionally, the decrease in Young’s modulus (caused by weakened In-O chemical bonds after doping) reduces phonon propagation velocity (v ∝ √(E/ρ), where E is Young’s modulus and ρ is density). Since κ

l is proportional to the product of specific heat capacity, phonon velocity, and mean free path (κ

l ∝ C

vv l

ph), the combined effect of reduced phonon velocity and shortened mean free path leads to a significant drop in κ

l. Although the increase in carrier concentration slightly enhances κ

e, the dominant reduction in κ

l ultimately results in a decrease in total thermal conductivity, further optimizing the ZT value. The significant improvement in ZT value (from 0.055 to 0.358) is the result of the synergistic effect of power factor enhancement and thermal conductivity reduction, both of which are rooted in the structural and electronic regulation induced by La doping. On the one hand, La doping optimizes electronic transport: increasing carrier concentration to enhance electrical conductivity, and inducing band convergence to maintain a moderate Seebeck coefficient, thereby boosting the power factor. On the other hand, it suppresses thermal transport: lattice distortion and reduced Young’s modulus jointly reduce lattice thermal conductivity, and the dominant contribution of κ

l ensures a decrease in total thermal conductivity. This “promoting electricity and suppressing heat” regulation creates a positive cycle: the power factor enhancement increases the numerator of ZT, while the thermal conductivity reduction decreases the denominator. At the same time, the elevated carrier concentration (from doping) balances the trade-off between electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient, and the lattice distortion balances the relationship between mechanical properties (Young’s modulus) and thermal transport properties. The comprehensive effect of these factors ultimately leads to a six-fold increase in the ZT value of La-doped In

2O

3, significantly improving its thermoelectric energy conversion efficiency.

For La-doped indium oxide (In

2O

3) thermoelectric materials, the simultaneous enhancement of Vickers hardness as shown in

Figure 9b, electrical conductivity, and power factor—along with the reduction of Seebeck coefficient, total thermal conductivity, and lattice thermal conductivity—originates from the structural optimization and chemical bond regulation induced by La doping. The introduction of La modifies the lattice structure, interatomic bonding, and defect state of In

2O

3, which not only optimizes thermoelectric transport properties but also significantly improves mechanical hardness. In

2O

3 has a cubic bixbyite structure, where In

3+ ions are coordinated with oxygen atoms to form a stable lattice framework. The ionic radius of La

3+ (103 pm) is larger than that of In

3+ (80 pm). When La

3+ replaces In

3+ in the lattice, the mismatch in ionic radius causes local lattice expansion and distortion. This lattice distortion generates a uniform internal stress field in the material. During the Vickers hardness test, the external indentation force needs to overcome both the intrinsic interatomic bonding force and the resistance from the internal stress field. The superposition of these two resistances increases the difficulty of plastic deformation of the lattice, thereby enhancing the Vickers hardness. Meanwhile, the lattice distortion caused by doping is relatively uniform (without obvious crack formation), which avoids the degradation of mechanical properties and ensures that the hardness is effectively improved. Vickers hardness is closely related to the strength of interatomic chemical bonds in the material—stronger interatomic bonding leads to higher resistance to external deformation and thus higher hardness. La doping modifies the chemical bond characteristics of In

2O

3, enhancing the overall interatomic bonding strength. In the In

2O

3 lattice, In-O bonds are mainly ionic bonds with partial covalent characteristics. The electronegativity of La (1.10) is lower than that of In (1.78). When La replaces In, the electron cloud distribution around the oxygen atoms is rearranged. The stronger electron-donating ability of La

3+ enhances the ionic component of the La-O bond compared to the In-O bond. At the same time, the lattice distortion caused by doping increases the overlap degree of electron orbitals between adjacent atoms, enhancing the covalent characteristic of the chemical bonds. The synergistic enhancement of ionic and covalent components in the chemical bonds significantly improves the interatomic bonding strength of the material, laying a fundamental foundation for the increase in Vickers hardness. La doping introduces substitutional defects (La_In) into the In

2O

3 lattice, and the charge compensation effect generates additional free electrons to optimize thermoelectric transport properties. These substitutional defects also play a key role in enhancing hardness. Substitutional defects (La_In) act as “pinning points” in the lattice. During the plastic deformation process induced by indentation, the movement of dislocations is hindered by these defect sites. The interaction between dislocations and substitutional defects increases the energy required for dislocation slip, thereby inhibiting plastic deformation and improving hardness. Meanwhile, the uniform distribution of La_In defects avoids local stress concentration, which not only ensures the stability of mechanical properties but also promotes phonon scattering (contributing to the reduction of lattice thermal conductivity). This synergistic regulation of defects—optimizing both “mechanical hardness” and “thermal transport inhibition”—realizes the simultaneous improvement of mechanical and thermoelectric properties of La-doped In

2O

3.

3. Experimental Part

High-purity indium oxide (In2O3) and lanthanum oxide (La2O3) powders were chosen as raw materials. The powders underwent pre-treatment to guarantee uniformity prior to application. A planetary ball mill was utilized for mechanical alloying to fabricate La-doped In2O3 powder. In2O3 and La2O3 powders with stoichiometric ratios (LaxIn2−xO3, x = 0, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075, 0.0085), corresponding to the preset La doping concentration in molar proportion, were thoroughly blended and loaded into hardened steel jars together with appropriate grinding balls. The milling procedure was conducted under argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation, with intermittent cooling applied to avoid overheating. Subsequently, the mechanically alloyed powders were pressed into pellets and sintered via spark plasma sintering (SPS). Before sintering, the pellets were placed in graphite dies, and the SPS process was executed in an inert gas (argon) environment to minimize contamination. The weighed powder was placed into a ball milling tank for 10 h with the speed of 450 rpm and the ball/material ratio of 20:1, then anhydrous ethanol was added, and ball milling with a planetary ball mill (QM-2SP12, Nanjing University Instrument Factory, Nanjing, China) was carried out for 1 h with the speed of 300 rpm, followed by drying the obtained powder for more than 48 h at the temperature of 373 K. Then the obtained powder was placed into a quartz tube, which was filled with argon gas for protection, and sealed. It was placed in a muffle furnace and calcined at a high temperature of 1473 K for 8 h. The obtained sample was crushed and then discharge plasma sintering was performed at a temperature of 1273 K with 30 min of insulation and a pressure of 60 MPa. For the SPS process, the pellets were carefully positioned within specialized graphite molds. The entire sintering cycle was executed under a continuous flow of inert argon gas to maintain sample purity and minimize atmospheric contamination. The sintered bulk sample was a cylinder with a diameter of 20mm and a height of 13mm, which is then subjected to cutting tests. The mass of the samples (LaxIn2−xO3, x = 0, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075, 0.0085) was 28.55 g, 28.60 g, 28.61 g, 28.59 g, 28.57 g, 28.61 g, respectively. A diffractometer was used to characterize the phase structure of the bulk samples, and the equipment is a Bruker AXS D8 diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The diffraction analysis adopted Cu and rays with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å. Nickel plates were used as the substrate on the XRD sample stage with a diffraction angle range of 10–80°, a step size of 0.02°, a tube current of 20 mA, and a tube voltage of 40 kV. The electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient were tested using an electrical performance tester (ZEM-3, ULVAC KIKO, Tokyo, Japan). The carrier concentration and mobility at room temperature were measured by the van der Pauw method using the Hall-effect measurement system (HMS-5500, Ekopia, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The volume density was measured by the Archimedes method. The flash thermal conductivity tester used was LFA457 (Netzsch, Berlin, Germany), Germany, for thermal conductivity testing. And the specific heat capacity (Cp) was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC 404C, Netzsch, Berlin, Germany) under an inert atmosphere. All the specimens were polished with two parallel planes and the plane close to the central part was utilized for Vickers hardness (HV) measurement, which was conducted on Vickers hardness tester (HV-10008, Dongguan Guangtai Precision Instrument Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China) with a load of 25 g and a loading time of 15 s. Every sample was tested with 5 data points, and the average HV was used for characterizing mechanical properties. The uncertainty of the Vickers hardness is estimated to be within 5%. The uncertainty of the Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity measurements was 5%. The uncertainty of the thermal conductivity is estimated to be within 8%, considering the uncertainties regarding thermal diffusion coefficient, specific heat, and density. The combined uncertainty for all measurements involved in the calculation of ZT is less than 15%. The density functional calculation used here is the CASTEP software 8.0 package in the materials studio software 8.0, and the constructed 2 × 2 × 1 unit cell is calculated. The cut-off energy in plane wave expansion is 550 eV, the total energy is converged to less than 2.0 × 10−5 eV/atom. The maximum stress and maximum force were converged to less than 0.05 GPa and 0.3 eV/nm. The tolerance in the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation was set to 10−6 eV/atom.