Extending Hexagon-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks—Mn(II) and Gd(III) MOFs with Hexakis(4-(4-Carboxyphenyl)phenyl)benzene

Abstract

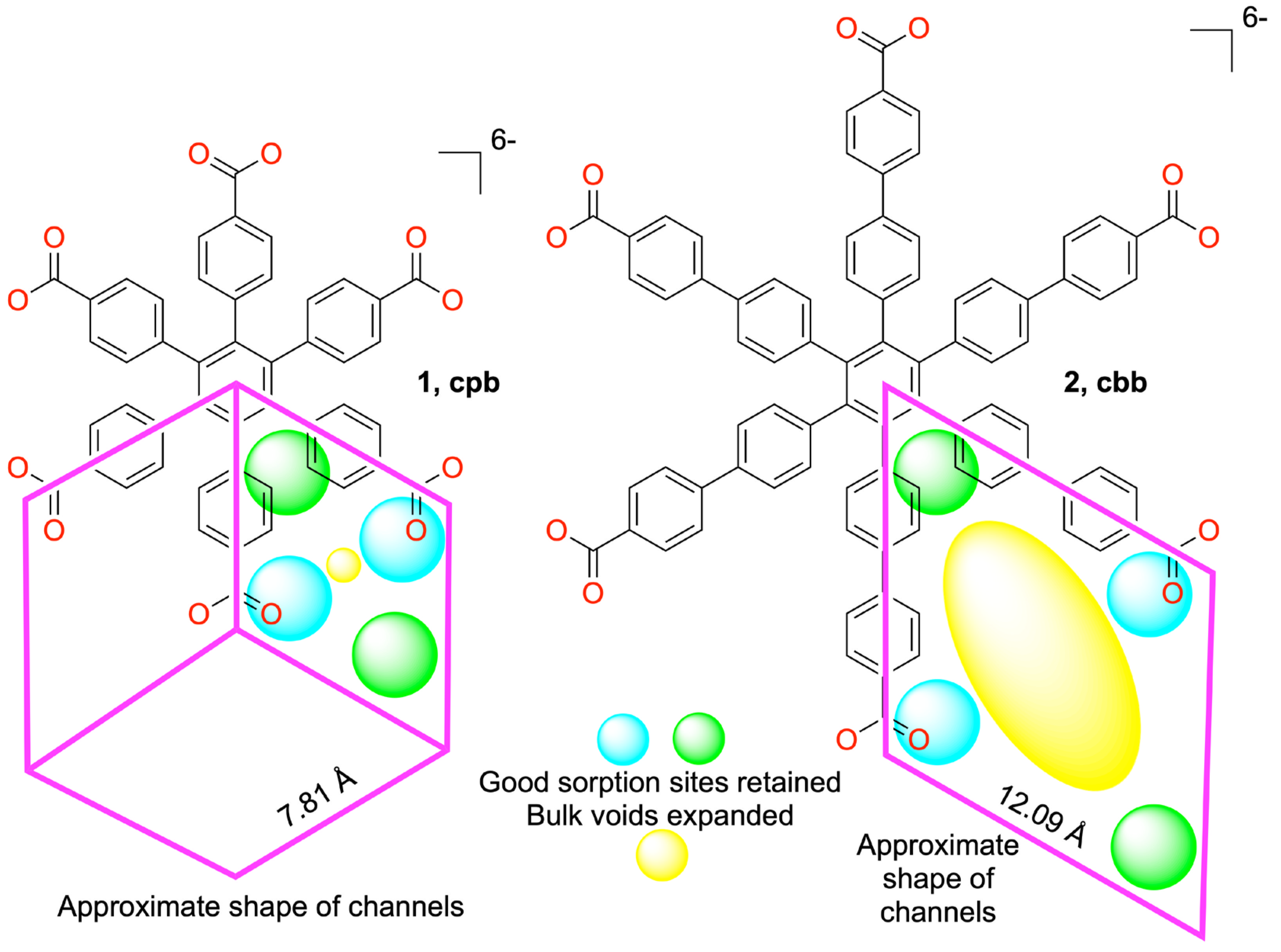

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

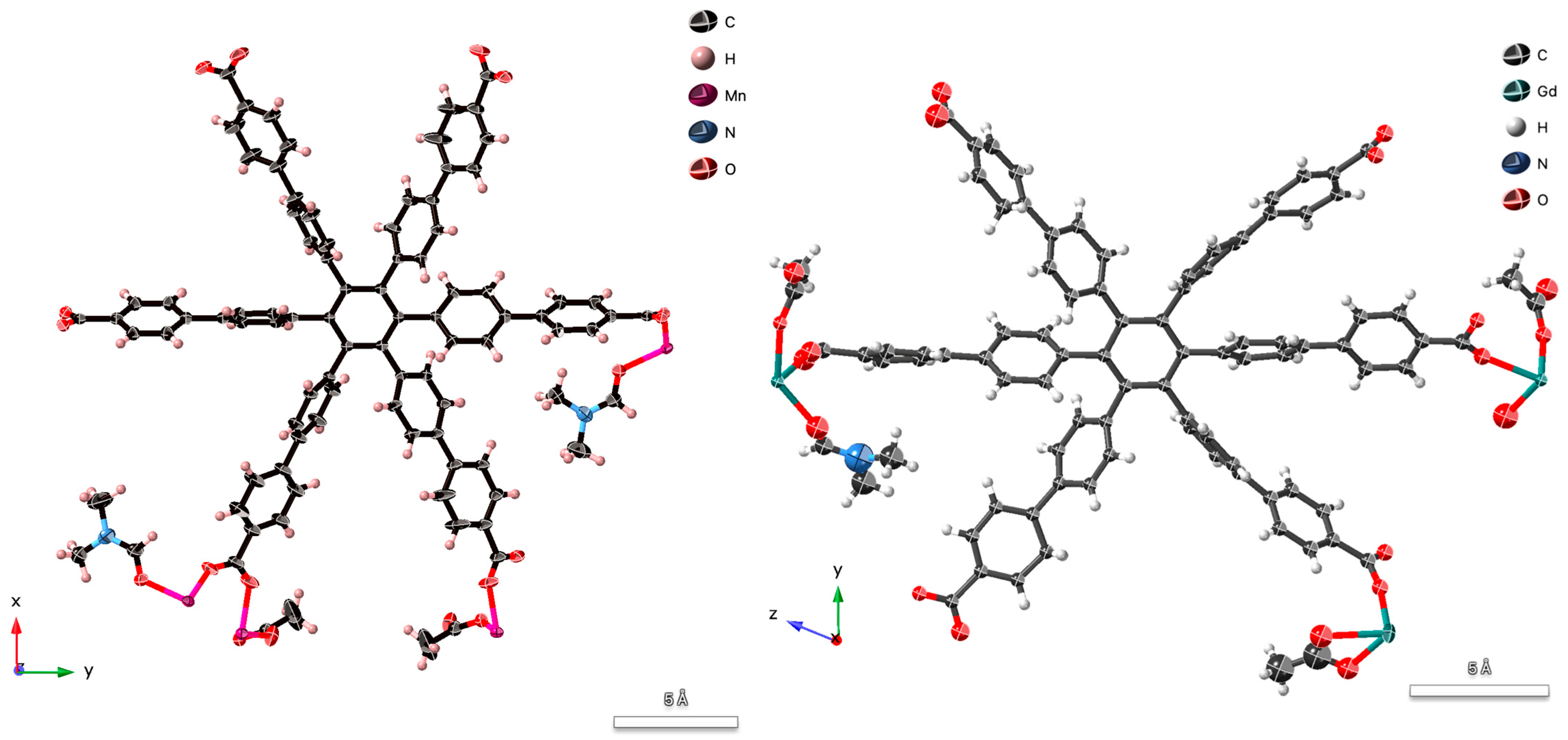

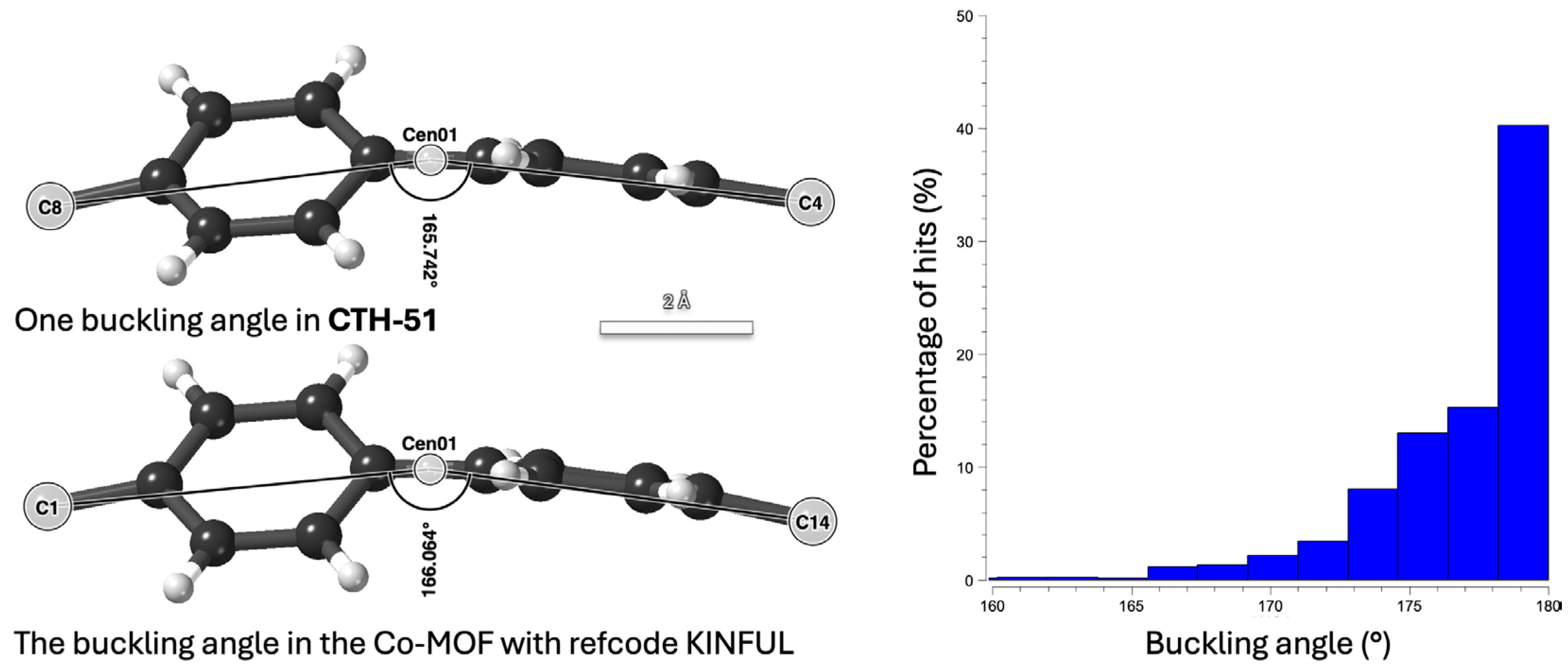

2.2. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

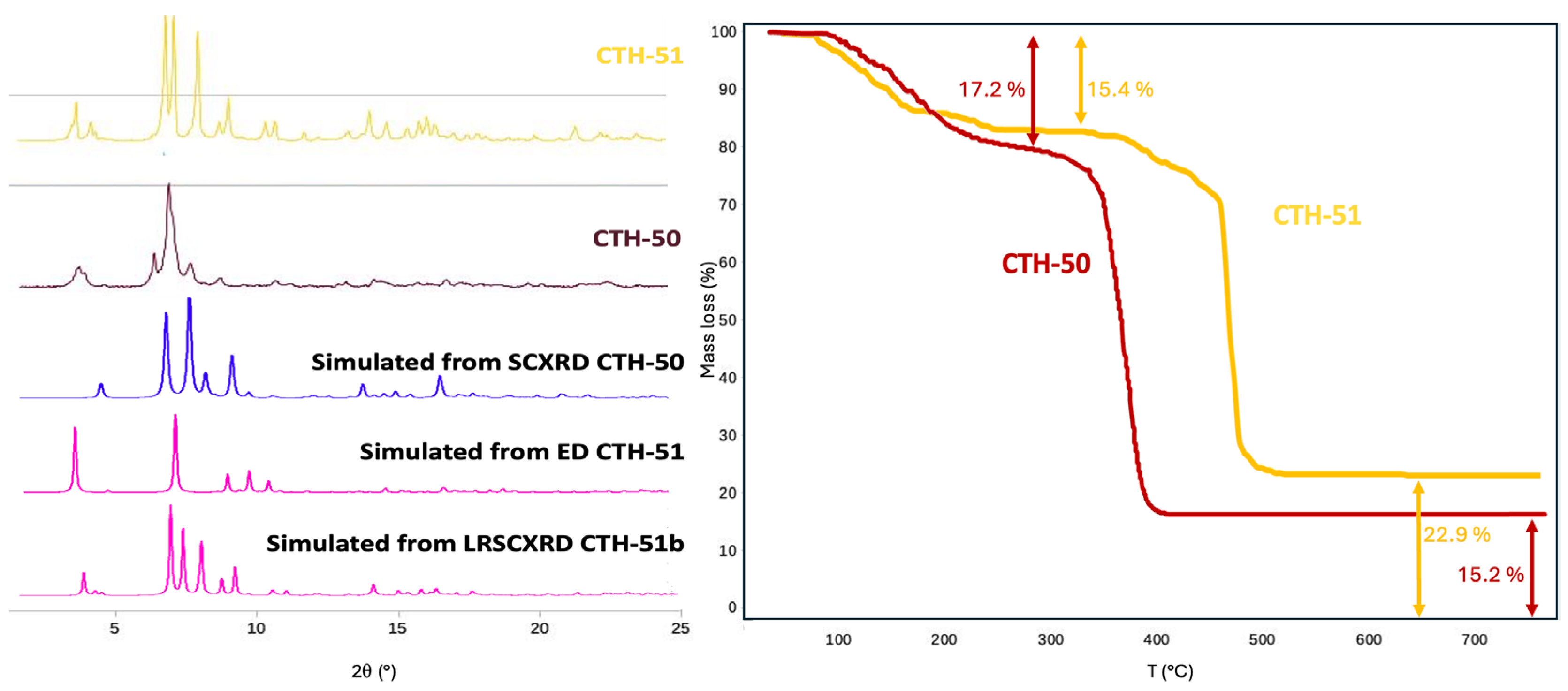

2.3. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.5. Gas Sorption Analysis

2.6. Network Topology Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopic (TEM) Analysis

3.3. Continuous-Rotation Electron Diffraction (cRED) Collection

3.4. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

3.5. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

3.6. Gas Adsorption Isotherms

3.7. Other Tools

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, G.M.; Li, H.L. Selective Binding and Removal of Guests in a Microporous Metal-Organic Framework. Nature 1995, 378, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 1999, 402, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, S.R.; Champness, N.R.; Chen, X.M.; Garcia-Martinez, J.; Kitagawa, S.; Öhrström, L.; O’Keeffe, M.; Suh, M.P.; Reedijk, J. Terminology of metal-organic frameworks and coordination polymers (IUPAC Recommendations 2013). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.L.; Fahy, K.M.; Morris, W.; Dravid, V.P.; Hernandez, B.; Farha, O.K. The Road Ahead for Metal–Organic Frameworks: Current Landscape, Challenges and Future Prospects. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmutzki, M.J.; Hanikel, N.; Yaghi, O.M. Secondary building units as the turning point in the development of the reticular chemistry of MOFs. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortín-Rubio, B.; Ghasempour, H.; Guillerm, V.; Morsali, A.; Juanhuix, J.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Net-Clipping: An Approach to Deduce the Topology of Metal–Organic Frameworks Built with Zigzag Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9135–9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortín-Rubio, B.; Rostoll-Berenguer, J.; Vila, C.; Proserpio, D.M.; Guillerm, V.; Juanhuix, J.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Net-clipping as a top-down approach for the prediction of topologies of MOFs built from reduced-symmetry linkers. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12984–12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.F. Three-Dimensional Nets and Polyhedra; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, R. A net-based approach to coordination polymers. Dalton Trans. 2000, 21, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.; Fischer, W. Sphere packings with three contacts per sphere and the problem of the least dense sphere packing. Z. Krist. 1995, 210, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Three-periodic nets and tilings: Edge-transitive binodal structures. Acta Cryst. A 2006, 62, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M. Three-periodic tilings and nets: Face-transitive tilings and edge-transitive nets revisited. Acta Cryst. A 2007, 63, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M. Identification and symmetry computation for crystal nets. Acta Cryst. Sec. A 2003, 59, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amombo Noa, F.M.; Svensson Grape, E.; Brülls, S.M.; Cheung, O.; Malmberg, P.; Inge, A.K.; McKenzie, C.J.; Mårtensson, J.; Öhrström, L. Metal–Organic Frameworks with Hexakis(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene: Extensions to Reticular Chemistry and Introducing Foldable Nets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9471–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.; Yan, T.; Wei, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.-F. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Single-Molecule SF6 Trap for Record SF6 Capture. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 9134–9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhlén, M.; Amombo Noa, F.M.; Öhrström, L.; Hedbom, D.; Strømme, M.; Cheung, O. Pore size effect of 1,3,6,8-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)pyrene-based metal-organic frameworks for enhanced SF6 adsorption with high selectivity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 343, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Gu, Y. Molecular Mechanism Behind the Capture of Fluorinated Gases by Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Ke, T.; Jin, Y.; Fan, R.; Xu, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Z.; Ren, Q.; et al. Efficient continuous SF6/N2 separation using low-cost and robust metal-organic frameworks composites. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amombo Noa, F.M.; Cheung, O.; Åhlén, M.; Ahlberg, E.; Nehla, P.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Ershadrad, S.; Sanyal, B.; Öhrström, L. A hexagon based Mn(II) rod metal–organic framework—Structure, SF6 gas sorption, magnetism and electrochemistry. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 2106–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, S.G.; Gupta, N.K.; Reynolds, J.E., III; Sagastuy-Breña, M.; Flores, J.G.; Martínez-Ahumada, E.; Sánchez-González, E.; Lynch, V.M.; Gutiérrez-Alejandre, A.; Aguilar-Pliego, J.; et al. Mn-CUK-1: A Flexible MOF for SO2, H2O, and H2S Capture. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 15037–15044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, P.Z.; Chung, Y.G.; Snurr, R.Q. Progress toward the computational discovery of new metal–organic framework adsorbents for energy applications. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M.; Ke, G.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, Z.; Lu, D. A comprehensive transformer-based approach for high-accuracy gas adsorption predictions in metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhlén, M.; Jaworski, A.; Strømme, M.; Cheung, O. Selective adsorption of CO2 and SF6 on mixed-linker ZIF-7–8s: The effect of linker substitution on uptake capacity and kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 130117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alezi, D.; Spanopoulos, I.; Tsangarakis, C.; Shkurenko, A.; Adil, K.; Belmabkhout, Y.; O′Keeffe, M.; Eddaoudi, M.; Trikalitis, P.N. Reticular Chemistry at Its Best: Directed Assembly of Hexagonal Building Units into the Awaited Metal-Organic Framework with the Intricate Polybenzene Topology, pbz-MOF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12767–12770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Cryst. B 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A.; Colón, Y.J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.C.; Chen, Y.-S.; Hupp, J.T.; Yildirim, T.; Farha, O.K.; Zhang, J.; Snurr, R.Q. Evaluating topologically diverse metal–organic frameworks for cryo-adsorbed hydrogen storage. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3279–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanopoulos, I.; Tsangarakis, C.; Barnett, S.; Nowell, H.; Klontzas, E.; Froudakis, G.E.; Trikalitis, P.N. Directed assembly of a high surface area 2D metal–organic framework displaying the augmented “kagomé dual” (kgd-a) layered topology with high H2 and CO2 uptake. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jia, J.; Shkurenko, A.; Chen, Z.; Adil, K.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Weselinski, L.J.; Assen, A.H.; Xue, D.-X.; O’Keeffe, M.; et al. Enriching the Reticular Chemistry Repertoire: Merged Nets Approach for the Rational Design of Intricate Mixed-Linker Metal–Organic Framework Platforms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8858–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Song, F.; Cao, J.; Yan, C.-H.; Tang, Y. Rare Earth Complex-Based Functional Materials: From Molecular Design and Performance Regulation to Unique Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Grape, E.S.; Li, J.; Inge, A.K.; Zou, X. 3D electron diffraction as an important technique for structure elucidation of metal-organic frameworks and covalent organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 427, 213583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Wang, Y.; Carraro, F.; Liang, W.; Roostaeinia, M.; Siahrostami, S.; Proserpio, D.M.; Doonan, C.; Falcaro, P.; Zheng, H.; et al. High-Throughput Electron Diffraction Reveals a Hidden Novel Metal–Organic Framework for Electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11391–11397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilhufe, R.M. Quantum Buckling in Metal–Organic Framework Materials. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 10341–10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, N.; Öhrström, L.; Geilhufe, R.M. Collective Buckling in Metal-Organic Framework Materials. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-N.; Ni, J.-L.; Wang, J. A new two-dimensional CoII coordination polymer based on bis[4-(2-methyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl] ether and biphenyl-4,4′-diyldicarboxylic acid: Synthesis, crystal structure and photocatalytic degradation activity. Acta Cryst. C 2018, 74, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, T.C.; Colwell, C.E.; Zakharov, L.N.; Jasti, R. Symmetry breaking and the turn-on fluorescence of small, highly strained carbon nanohoops. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 3786–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-B.; Yoon, T.-U.; Hong, D.-Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, S.-I.; Lee, S.-K.; Chang, J.-S.; Bae, Y.-S. High SF6/N2 selectivity in a hydrothermally stable zirconium-based metal–organic framework. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 276, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grape, E.S.; Xu, H.; Cheung, O.; Calmels, M.; Zhao, J.; Dejoie, C.; Proserpio, D.M.; Zou, X.; Inge, A.K. Breathing Metal–Organic Framework Based on Flexible Inorganic Building Units. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amombo Noa, F.M.; Grape, E.S.; Åhlén, M.; Reinholdsson, W.E.; Göb, C.R.; Coudert, F.-X.; Cheung, O.; Inge, A.K.; Öhrström, L. Chiral Lanthanum Metal–Organic Framework with Gated CO2 Sorption and Concerted Framework Flexibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 8725–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazem, C.L.F.; Ruser, N.; Grape, E.S.; Inge, A.K.; Proserpio, D.M.; Stock, N.; Öhrström, L.R. How metal ions link in Metal-Organic Frameworks: Dots, rods, sheets, and 3D Secondary Building Units exemplified by a Y(III) 4,4\′92-oxydibenzoate. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 5659–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amombo Noa, F.M.; Abrahamsson, M.; Ahlberg, E.; Cheung, O.; Göb, C.R.; McKenzie, C.J.; Öhrström, L. A unified topology approach to dot-, rod-, and sheet-MOFs. Chem 2021, 7, 2491–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.; Patil, K.M.; Wilson, B.H.; Hermanspahn, L.; Harvey-Reid, N.C.; Howard, B.I.; Kleinjan, C.; Kolien, J.; Payet, F.; Telfer, S.G.; et al. The thermal stability of metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 419, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhrström, L. Designing, Describing and Disseminating New Materials by using the Network Topology Approach. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13758–13763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.G.; Haldoupis, E.; Bucior, B.J.; Haranczyk, M.; Lee, S.; Zhang, H.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Milisavljevic, M.; Ling, S.; Camp, J.S.; et al. Advances, Updates, and Analytics for the Computation-Ready, Experimental Metal–Organic Framework Database: CoRE MOF 2019. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 5985–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, E.V.; Blatov, V.A.; Kochetkov, A.V.; Proserpio, D.M. Underlying nets in three-periodic coordination polymers: Topology, taxonomy and prediction from a computer-aided analysis of the Cambridge Structural Database. Crystengcomm 2011, 13, 3947–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Kalmutzki, M.J.; Diercks, C.S. Introduction to Reticular Chemistry—Metal-Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko, A.P.; Alexandrov, E.V.; Golov, A.A.; Blatova, O.A.; Duyunova, A.S.; Blatov, V.A. Topology versus porosity: What can reticular chemistry tell about free space in metal-organic frameworks? Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 9616–9619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoedel, A.; Li, M.; Li, D.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Structures of Metal-Organic Frameworks with Rod Secondary Building Units. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12466–12535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.S.; Alexandrov, E.V.; Skorupskii, G.; Proserpio, D.M.; Dincă, M. Diverse π–π stacking motifs modulate electrical conductivity in tetrathiafulvalene-based metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 8558–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshuma, P.; Makhubela, B.C.E.; Öhrström, L.; Bourne, S.A.; Chatterjee, N.; Beas, I.N.; Darkwa, J.; Mehlana, G. Cyclometalation of lanthanum(III) based MOF for catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to formate. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 3593–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka, M.O.; Angstrom, J.; Wang, B.; Zou, X.; Smeets, S. High-throughput continuous rotation electron diffraction data acquisition via software automation. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2018, 51, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Cryst. D. 2010, 66, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Carraro, F.; Liang, W.; Doonan, C.; Falcaro, P.; Zheng, H.; Zou, X.; Huang, Z. On the completeness of three-dimensional electron diffraction data for structural analysis of metal–organic frameworks. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 231, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crysalis CCD; Oxford Diffraction Ltd.; Abingdon, UK, 2005; Available online: https://rigaku.com/products/crystallography/x-ray-diffraction/crysalispro.

- Crysalis RED; Oxford Diffraction Ltd.; Abingdon, UK, 2005; Available online: https://rigaku.com/products/crystallography/x-ray-diffraction/crysalispro.

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, O.; Liu, Q.; Bacsik, Z.; Hedin, N. Silicoaluminophosphates as CO2 sorbents. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 156, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Qmax (Langmuir) mmol/g | R2 | Qmax (Toth) mmol/g | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTH-18 | 1.89 | 0.99679 | (1.69) | (0.99885) |

| CTH-50 | 2.41 | 0.99968 | 2.67 | (0.99885) |

| MOF | Mn+ | Link | STR Type * | STR | PoE (p.s. #) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTH-50 | Mn(II) | cbb 2 | 5,6-c | yav | och | |

| CTH-51 | Gd(III) | cbb 2 | 5,6-c | yav | och | |

| CTH-17 | La(III) | cpb 1 | 5,6-c | yav | och | [38] |

| CTH-18 | Mn(II) | cpb 1 | 4,4,6-c | {52.63.7}{4.52.62.7}{4.54.66.74} # | {36.44.65}{611.74} # | [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Björck, H.; Reinholdsson, W.; Cheung, O.; Zhou, G.; Huang, Z.; Amombo Noa, F.M.; Öhrström, L. Extending Hexagon-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks—Mn(II) and Gd(III) MOFs with Hexakis(4-(4-Carboxyphenyl)phenyl)benzene. Inorganics 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010012

Björck H, Reinholdsson W, Cheung O, Zhou G, Huang Z, Amombo Noa FM, Öhrström L. Extending Hexagon-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks—Mn(II) and Gd(III) MOFs with Hexakis(4-(4-Carboxyphenyl)phenyl)benzene. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjörck, Henrik, William Reinholdsson, Ocean Cheung, Guojon Zhou, Zhehao Huang, Francoise M. Amombo Noa, and Lars Öhrström. 2026. "Extending Hexagon-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks—Mn(II) and Gd(III) MOFs with Hexakis(4-(4-Carboxyphenyl)phenyl)benzene" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010012

APA StyleBjörck, H., Reinholdsson, W., Cheung, O., Zhou, G., Huang, Z., Amombo Noa, F. M., & Öhrström, L. (2026). Extending Hexagon-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks—Mn(II) and Gd(III) MOFs with Hexakis(4-(4-Carboxyphenyl)phenyl)benzene. Inorganics, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010012