On-Chip Volume Refractometry and Optical Binding of Nanoplastics Colloids in a Stable Optofluidic Fabry–Pérot Microresonator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theory and Mathematical Modeling

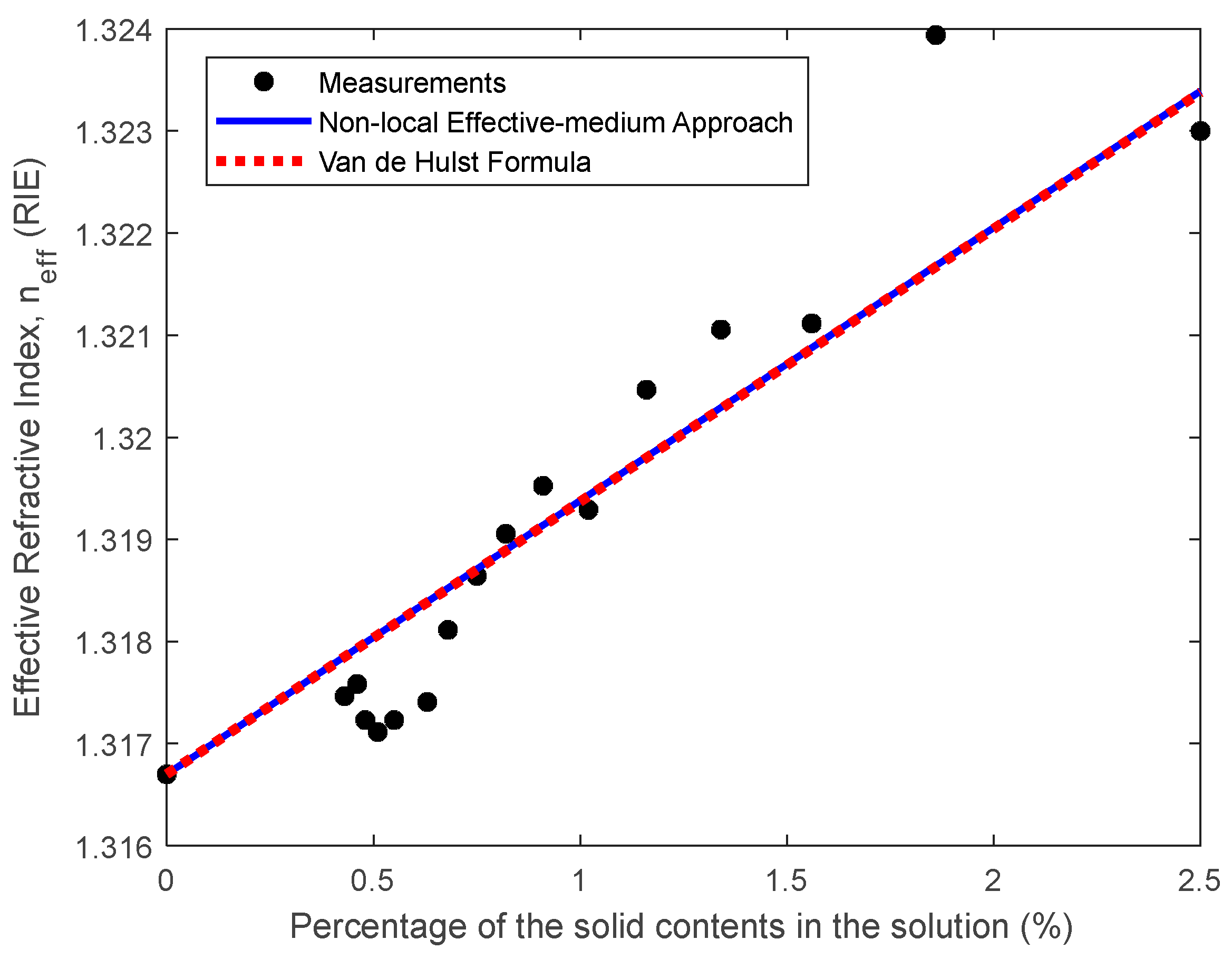

2.1.1. Van de Hulst Formula

2.1.2. Non-Local Effective-Medium Approach

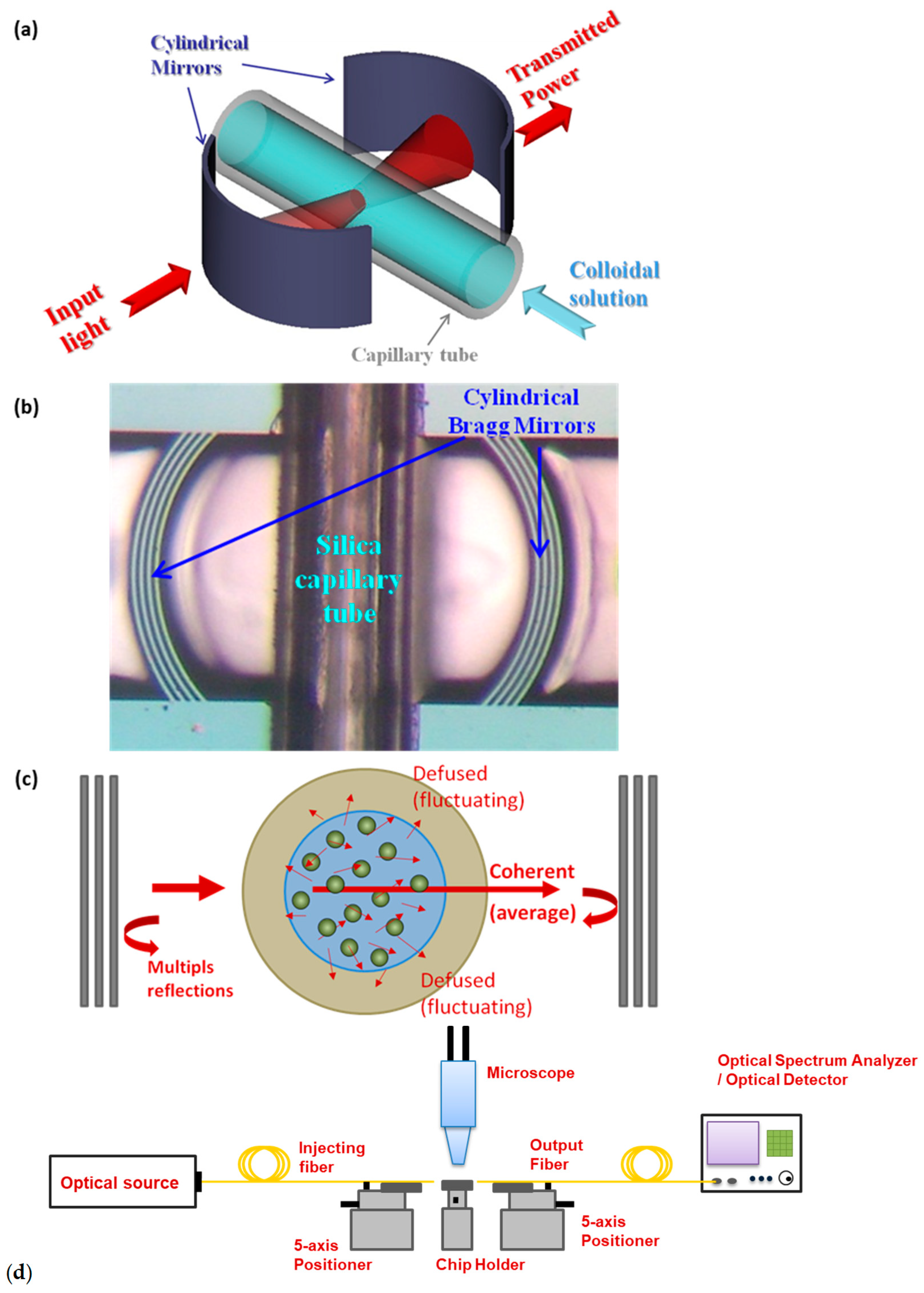

2.2. Experimental Setup

3. Results and Discussion

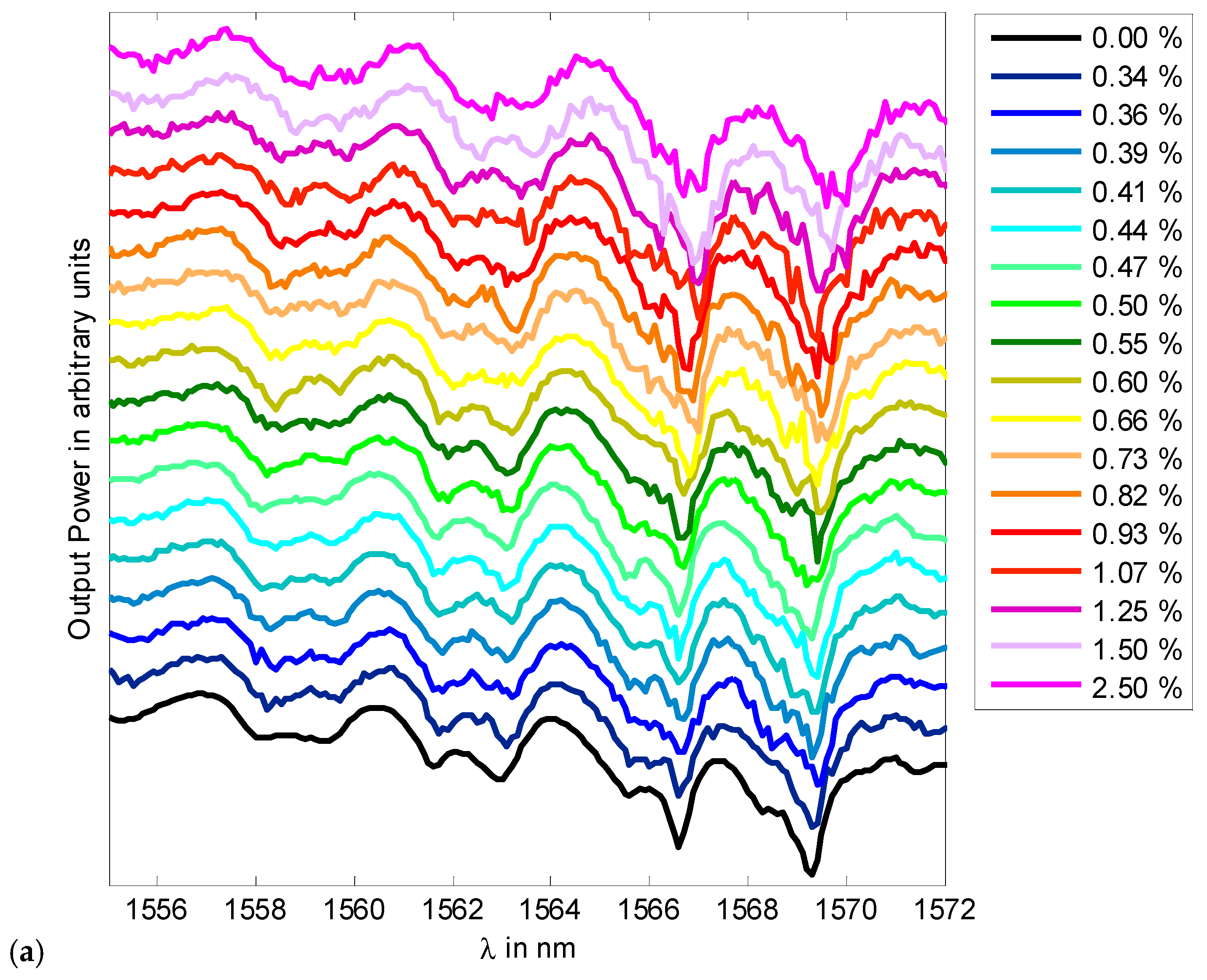

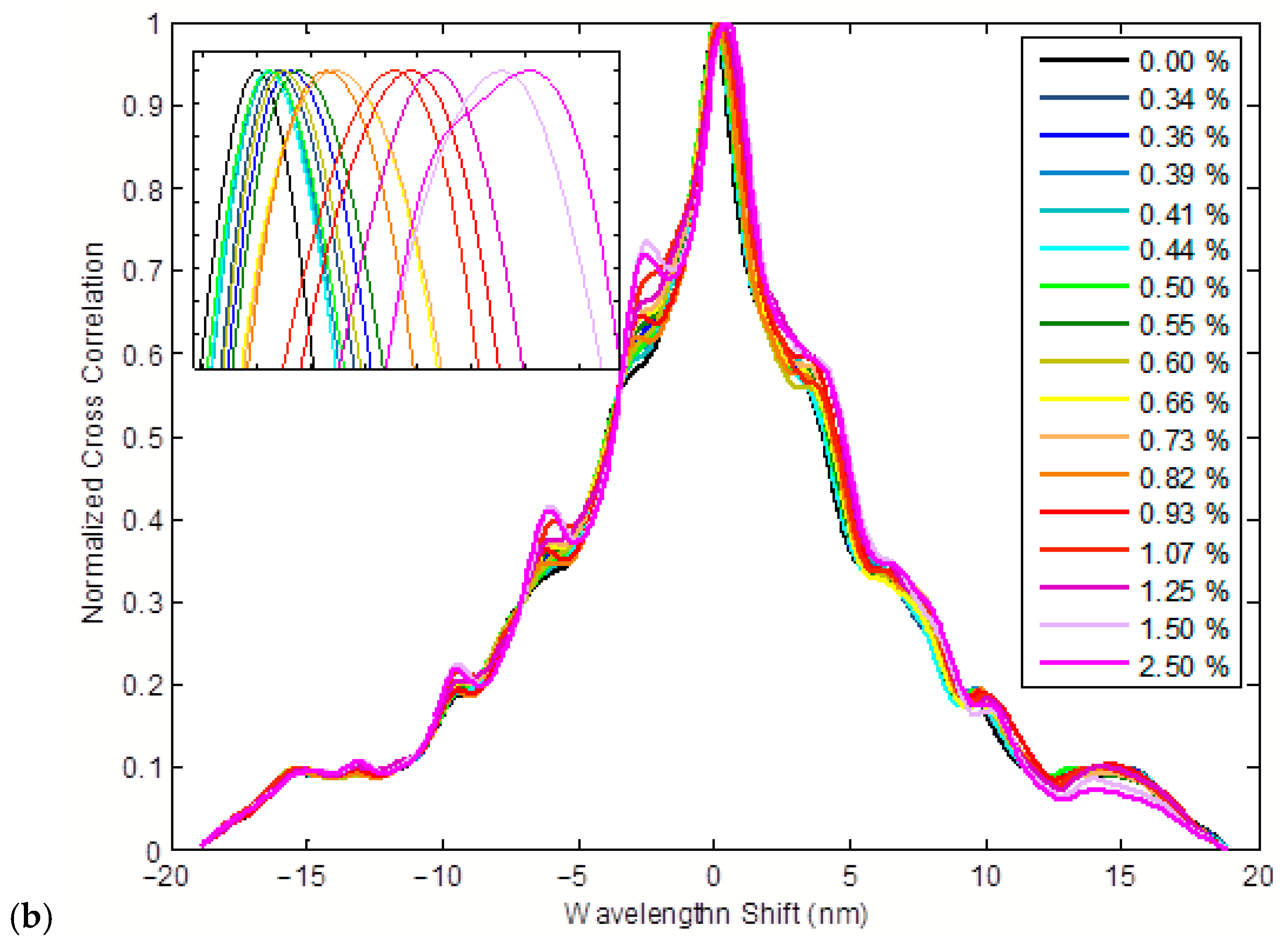

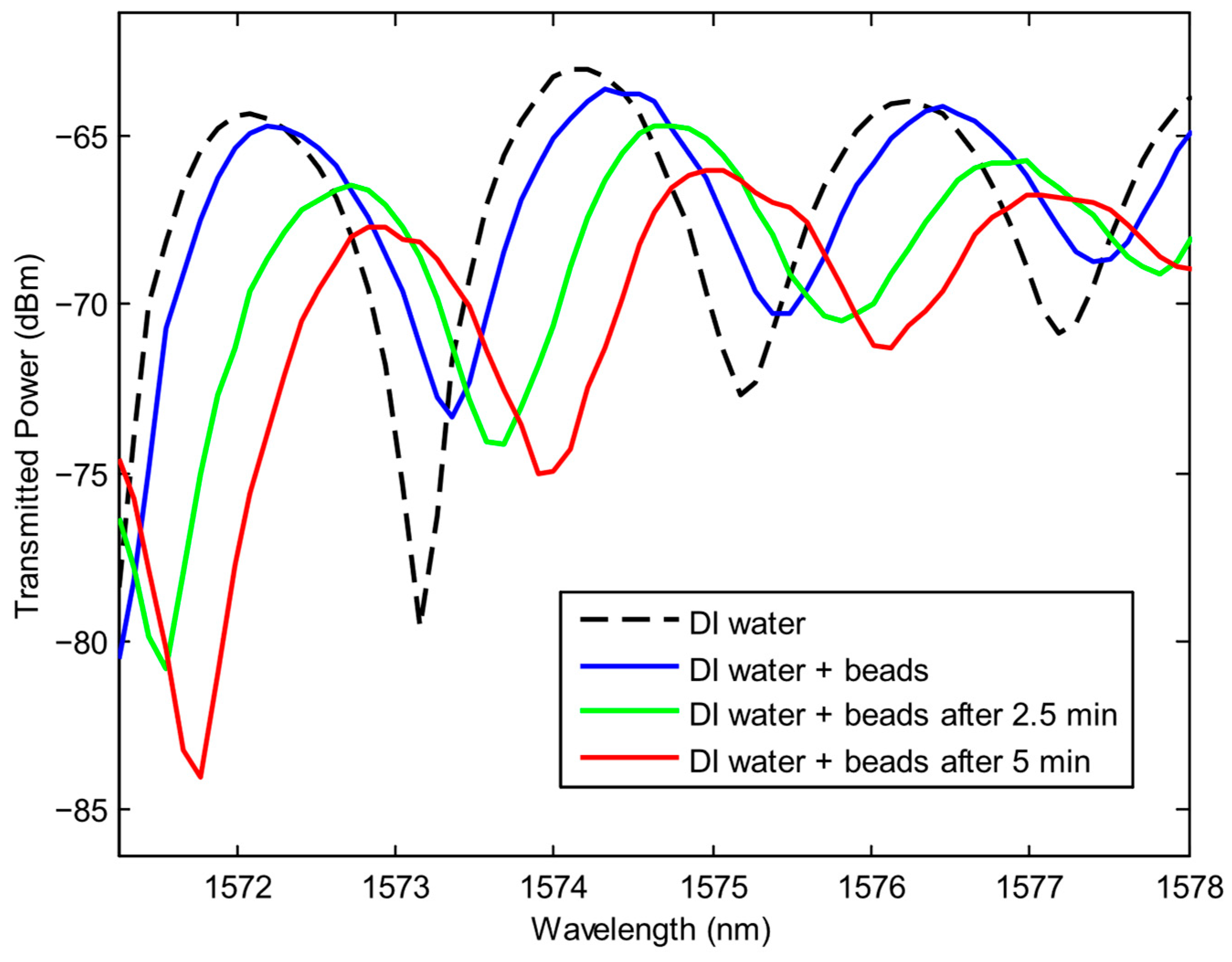

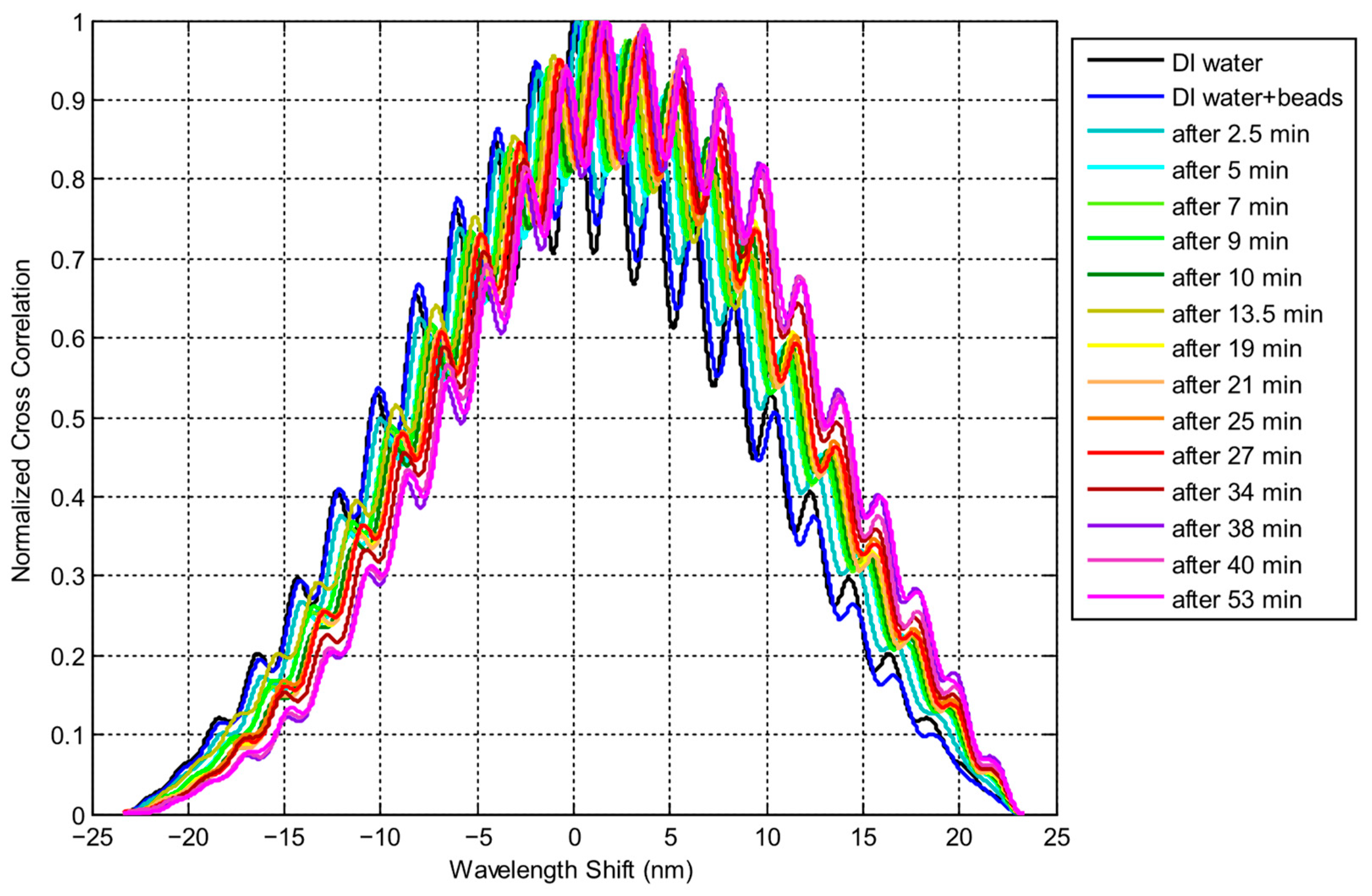

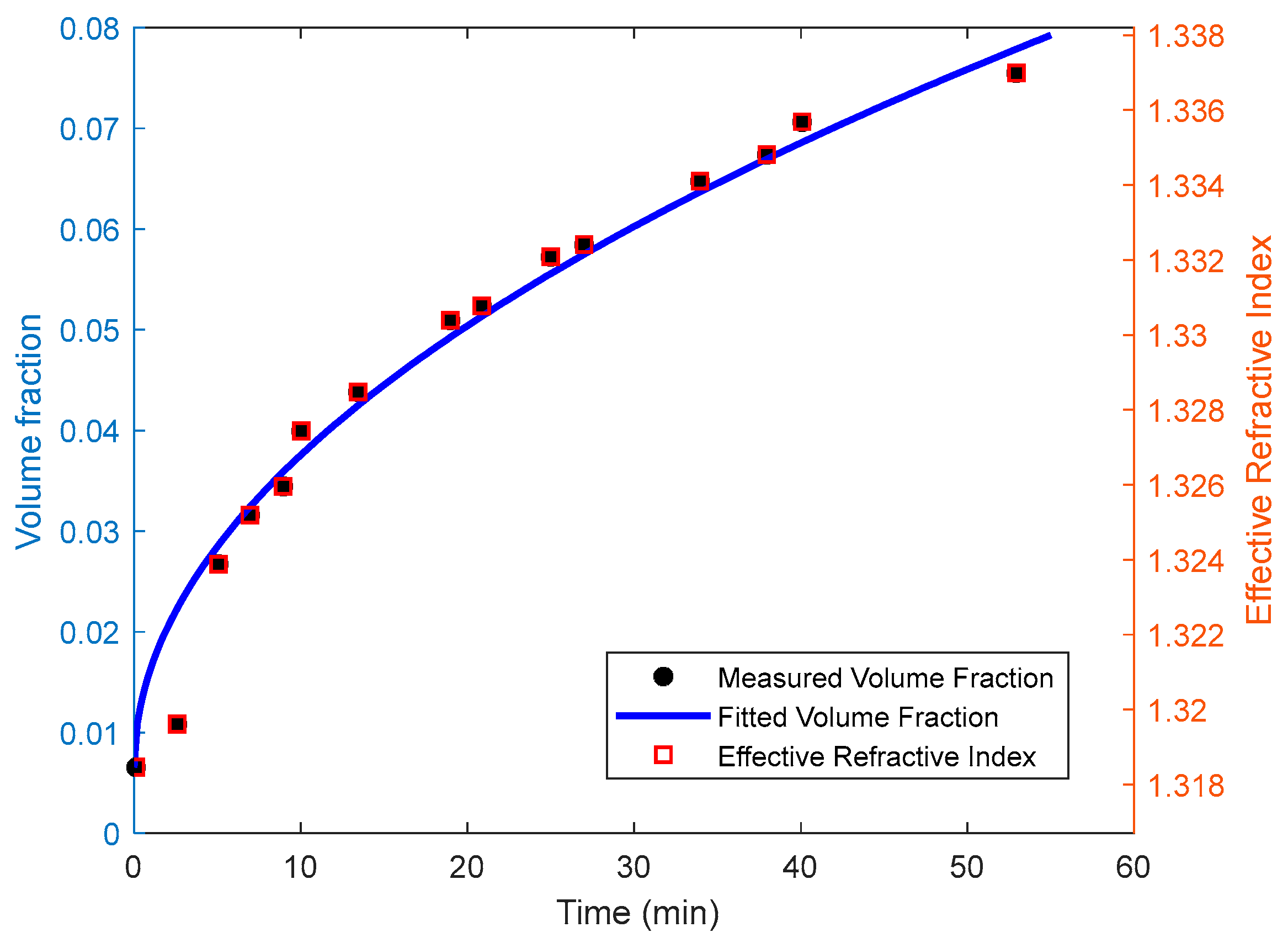

3.1. Colloidal Refractometry

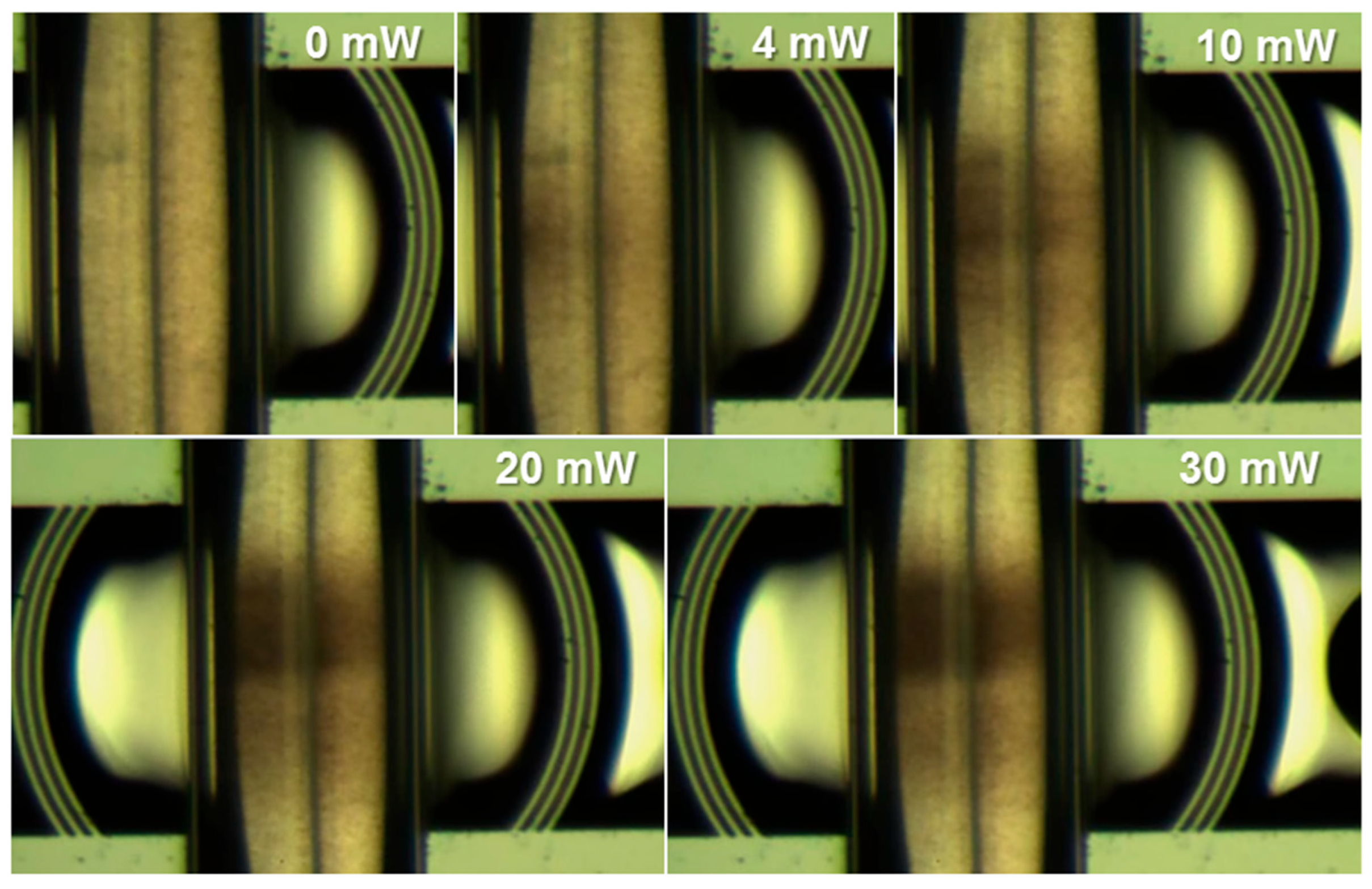

3.2. Particles Aggregation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of nanoplastic in the environment and possible impact on human health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarska, E.; Jutel, M.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. The potential impact of nano- and microplastics on human health: Understanding human health risks. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, T.; Ma, S.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Y. Unveiling the Environmental Characteristics of Sub-1000-nm Nanoplastics: A Comprehensive Review of the Preparation Methods for Nanoplastic Model Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 18391–18410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S.; Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A.A. Twenty years of microplastic pollution research—What have we learned? Science 2024, 386, eadl2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; Ter Halle, A.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current opinion: What is a nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Hao, L.; Tian, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, C.; Xue, J. Qualitative Discrimination and Quantitative Prediction of Microplastics in Ash Based on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Haave, M.; Underhaug, J.; Wang, W. Unlocking the Potential of NMR Spectroscopy for Precise and Efficient Quantification of Microplastics. Micropl. Nanopl. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Flores, J.A. The Emerging Field of Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry for (Micro)Nanoplastic Analysis: “The 3As” Analysis, Advances, and Applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 174, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Quiroz, O.; Luna-Moreno, D.; Sánchez-Álvarez, A.; Quintanilla-Villanueva, G.E.; Silva-Hernández, O.J.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.M.; Villarreal-Chiu, J.F. Measurement of the Effective Refractive Index of Suspensions Containing 5 µm Diameter Spherical Polystyrene Microparticles by Surface Plasmon Resonance and Scattering. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.Q.V.; Cruz, J.; Martins, J.; Teodósio, M.A.A.; Jockusch, S.; Ramamurthy, V.; Da Silva, J.P. Fluorescence sensing of microplastics on surfaces. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludescher, D.; Wesemann, L.; Schwab, J.; Karst, J.; Sulejman, S.B.; Ubl, M.; Clarke, B.O.; Roberts, A.; Giessen, H.; Hentschel, M. Optical sieve for nanoplastic detection, sizing and counting. Nat. Photon. 2025, 19, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaferts, C.; Sogne, V.; Welz, R.; Meier, F.; Klein, T.; Niessner, R.; Elsner, M.; Ivleva, N.P. Nanoplastic Analysis by On-line Coupling of Raman Microscopy and Field-Flow Fractionation Enabled by Optical Tweezers. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 2682–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gowen, A.; Xu, W.; Xu, J. Analysing Micro-and Nanoplastics with Cutting-Edge Infrared Spectroscopy Techniques: A Critical Review. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida, K.; Imoto, Y.; Saito, T.; Hara, J.; Kawabe, Y. A Novel and Simple Method for Measuring Nano/Microplastic Concentrations in Soil Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy with Optimal Wavelength Selection. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 280, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiponen, K.-E.; Räty, J.; Ishaq, U.; Pélisset, S.; Ali, R. Outlook on optical identification of micro- and nanoplastics in aquatic environments. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, A.J.; Peiponen, K.-E.; Räty, J.A. On Reflectometric Measurement of a Refractive Index of Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M. Colloidal refractometry: Meaning and measurement of refractive index for dispersions; the science that time forgot. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995, 62, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.; Killey, A.; Meeten, G.H.; Senior, M. Refractive index of concentrated colloidal dispersions. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1981, 77, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilio, S.C. A simple method to measure critical angles for high-sensitivity differential refractometry. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Fryd, M.M.; Huang, J.-R.; Mason, T.G. Optically probing nanoemulsion compositions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2455–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A. Maximum minimum reflectance of parallel-polarized light at interfaces between transparent and absorbing media. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1983, 73, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Vedam, K. Analytic solution of the pseudo-Brewster angle. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1986, 3, 1772–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A.; Ugbo, E.E. Angular range for reflection of p-polarized light at the surface of an absorbing medium with reflectance below that at normal incidence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2002, 19, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, J.V.; Meeten, G.H.; Senior, M. Refractive index of particles in the colloidal state. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1978, 74, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Coronado, A.; García-Valenzuela, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, C.; Barrera, R.G. Measurement of the effective refractive index of a turbid colloidal suspension using light refraction. New J. Phys. 2005, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, R.G.; Reyes-Coronado, A.; García-Valenzuela, A. On the effective response of colloidal systems. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 184202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeten, G.H. Refractive index errors in the critical-angle and the Brewster-angle methods applied to absorbing and heterogeneous materials. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1997, 8, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, I.; Räty, J.; Peiponen, K.-E. Complex refractive index of turbid liquids. Opt. Lett. 2007, 32, 862–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoun, W.R.; Maeta, H.; Combs, A.; Bali, L.M.; Bali, S. Measurement of the refractive index of highly turbid media. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 1224–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.L.; Goyal, K.G.; Worth, B.W.; Makkar, S.S.; Calhoun, W.R.; Bali, L.M.; Bali, S. Accurate in situ measurement of complex refractive index and particle size in intralipid emulsions. J. Biomed. Opt. 2013, 18, 087003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K.G.; Dong, M.L.; Kane, D.G.; Makkar, S.S.; Worth, B.W.; Bali, L.M.; Bali, S. Note: Refractive index sensing of turbid media by differentiation of the reflectance profile: Does error-correction work? Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012, 83, 086107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lu, J.Q.; Brock, R.S.; Jacobs, K.M.; Yang, P.; Hu, X.-H. Determination of complex refractive index of polystyrene microspheres from 370 to 1610 nm. Phys. Med. Biol. 2003, 48, 4165–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shybanov, E.B.; Haltrin, V.I. Modeling the Effective Refractive Index and Absorption Coefficient of a Turbid Medium with Polydisperse Particles. In Proceedings of the Oceans 2002. MTS/IEEE Conference, Biloxi, MS, USA, 29–31 October 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 1968–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, S.L. Optical properties of biological tissues: A review. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, R37–R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, P.D.; Dinsmore, A.D.; Yodh, A.G.; Pine, D.J. Diffuse-transmission spectroscopy: A structural probe of opaque colloidal mixtures. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, 4827–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, K.; Paul, D.G.; Hans, A.S. Effective refractive index and absorption of concentrated latex dispersions. Appl. Opt. 2000, 39, 3314–3322. [Google Scholar]

- Yingying, Z.; Jiancheng, L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhenhua, L. Determination of effective complex refractive index of a turbid liquid with surface plasmon resonance phase detection. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J.J.; Vartiainen, E.M.; Peiponen, K.-E. Retrieval of the complex permittivity of spherical nanoparticles in a liquid host material from a spectral surface plasmon resonance measurement. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 893–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erik, M.V.; Jarkko, J.S.; Peiponen, K.E. Method for extracting the complex dielectric function of nanospheres in a water matrix from surface-plasmon resonance data. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2005, 22, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valenzuela, A.; Barrera, R.G.; Gutiérrez-Reyes, E. The effective refractive index of turbid colloidal suspensions. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 19741–19746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Hulst, H.C. Light Scattering by Small Particles; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Meeten, G.H. Refraction by spherical particles in the intermediate scattering region. Opt. Commun. 1997, 134, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, J.V.; Meeten, G.H.; Senior, M. Refraction by spherical colloid particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1979, 72, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, J.V.; Meeten, G.H.; Senior, M. Optical turbidity and refraction in a dispersion of spherical colloidal particles. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1979, 75, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domachuk, P.; Littler, I.; Cronin-Golomb, M.; Eggleton, B. Optofluidic refractive index sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 093513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.Z.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, A.Q.; Lim, C.S.; Yap, P.H.; Hosseini, H.M.M. Refractive index measurement of single living cells using on-chip Fabry-Pérot cavity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 203901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.K.; Liu, A.Q.; Lim, C.S.; Zhang, X.M.; Ng, J.H.; Hao, J.Z.; Takahashi, S. Differential single living cell refractometry using grating resonant cavity with optical trap. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 243901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Wang, W.; Lana, S.; Lear, K. High-Q tunable photonic crystal microcavity with integrated liquid-crystal infiltration and heater for high-sensitivity refractive index sensing. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2008, 20, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.K.; Liu, A.Q.; Lim, C.S.; Lin, C.L.; Ayi, T.C.; Yap, P.H. An optofluidic volume refractometer using Fabry–Pérot resonator with tunable liquid microlenses. Biomicrofluidics 2010, 4, 024107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kisker, D.W.; Thamm, D.H.; Shao, H.; Lear, K.L. A high-throughput single-cell refractometer for monitoring cellular behavior. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- St-Gelais, R.; Masson, J.; Peter, Y.-A. Integrated Fabry–Pérot cavity based on SU-8 polymer for optofluidic sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 243905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.; Pavy, N.; Marty, F.; Peter, Y.-A.; Liu, A.Q.; Bourouina, T. Micromachined Fabry–Perot resonator combining submillimeter cavity length and high quality factor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 211113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.; Gaber, N.; Marty, F.; Pavy, N.; Richalot, E.; Bourouina, T. Analysis of Fabry-Perot optical micro-cavities based on coating-free all-Silicon cylindrical Bragg reflectors. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 2378–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.M.; Fournier, J.; Golovchenko, J.A. Optical binding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 1233–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaber, N.; Malak, M.; Marty, F.; Angelescu, D.E.; Richalot, E.; Bourouina, T. Particles Optical Trapping and Binding in Optofluidic Stable Fabry–Pérot Resonator with Single-Sided Injection. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 2259–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, R.W.; Padgett, M.J. Optical trapping of a microscopic sphere in a standing-wave optical field. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 026401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzobohatý, O.; Čižmár, T.; Karásek, V.; Šiler, M.; Dholakia, K.; Zemánek, P. Experimental and theoretical determination of optical binding forces. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 25389–25402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Pang, R.Y.; Zhang, R.; Miao, C.X.; Wu, X.Y.; Hou, X.S.; Zhong, C. Study of colloidal particle Brownian aggregation by low-coherence fiber optic dynamic light scattering. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 376, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, H.; Doi, M. Aggregation kinetics in electro-rheological fluids. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1991, 60, 2778–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gaber, N.; Marty, F.; Richalot, E.; Bourouina, T. On-Chip Volume Refractometry and Optical Binding of Nanoplastics Colloids in a Stable Optofluidic Fabry–Pérot Microresonator. Photonics 2026, 13, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010091

Gaber N, Marty F, Richalot E, Bourouina T. On-Chip Volume Refractometry and Optical Binding of Nanoplastics Colloids in a Stable Optofluidic Fabry–Pérot Microresonator. Photonics. 2026; 13(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaber, Noha, Frédéric Marty, Elodie Richalot, and Tarik Bourouina. 2026. "On-Chip Volume Refractometry and Optical Binding of Nanoplastics Colloids in a Stable Optofluidic Fabry–Pérot Microresonator" Photonics 13, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010091

APA StyleGaber, N., Marty, F., Richalot, E., & Bourouina, T. (2026). On-Chip Volume Refractometry and Optical Binding of Nanoplastics Colloids in a Stable Optofluidic Fabry–Pérot Microresonator. Photonics, 13(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010091