Moiré Effect with Refraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

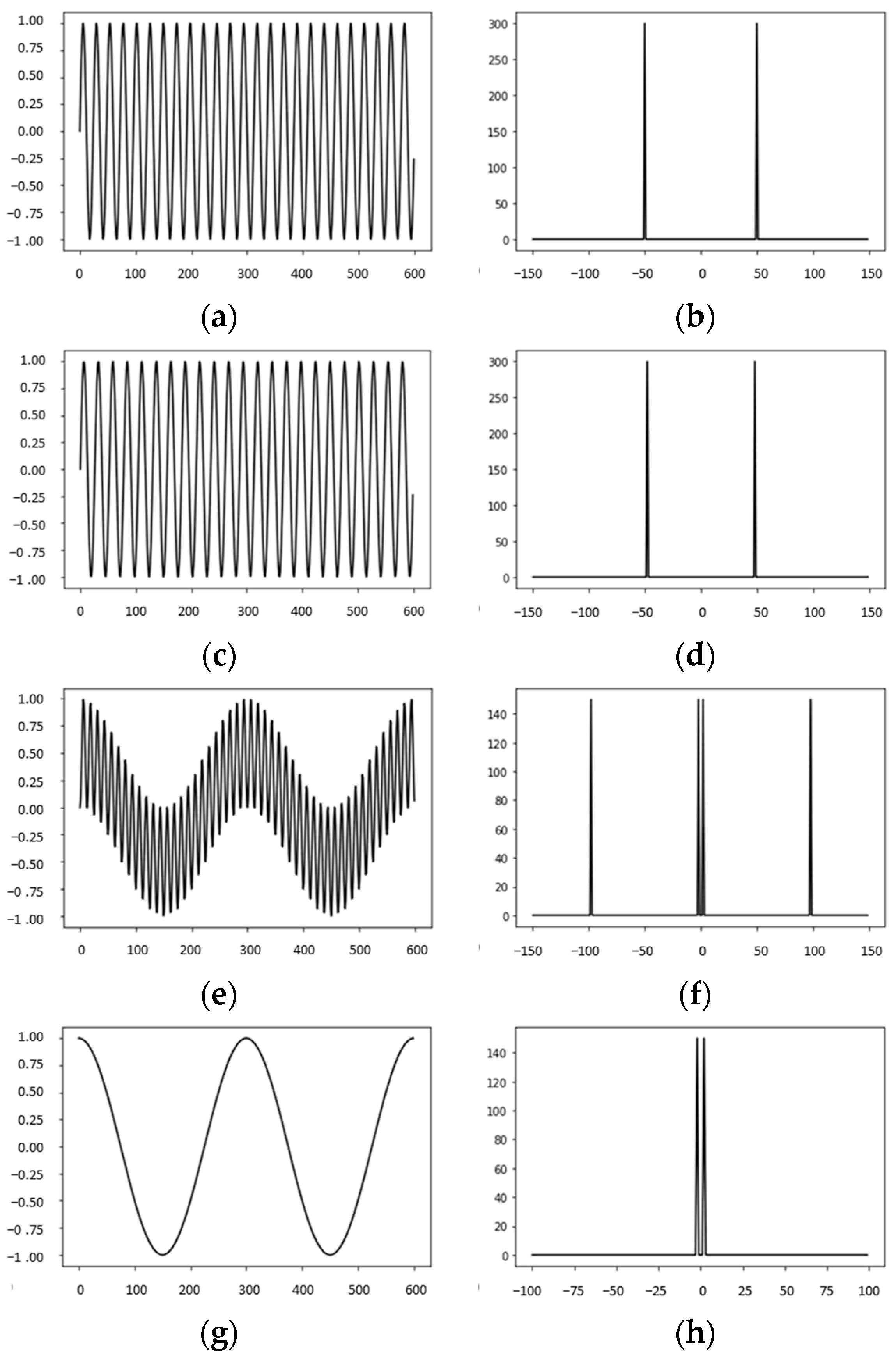

- (a)

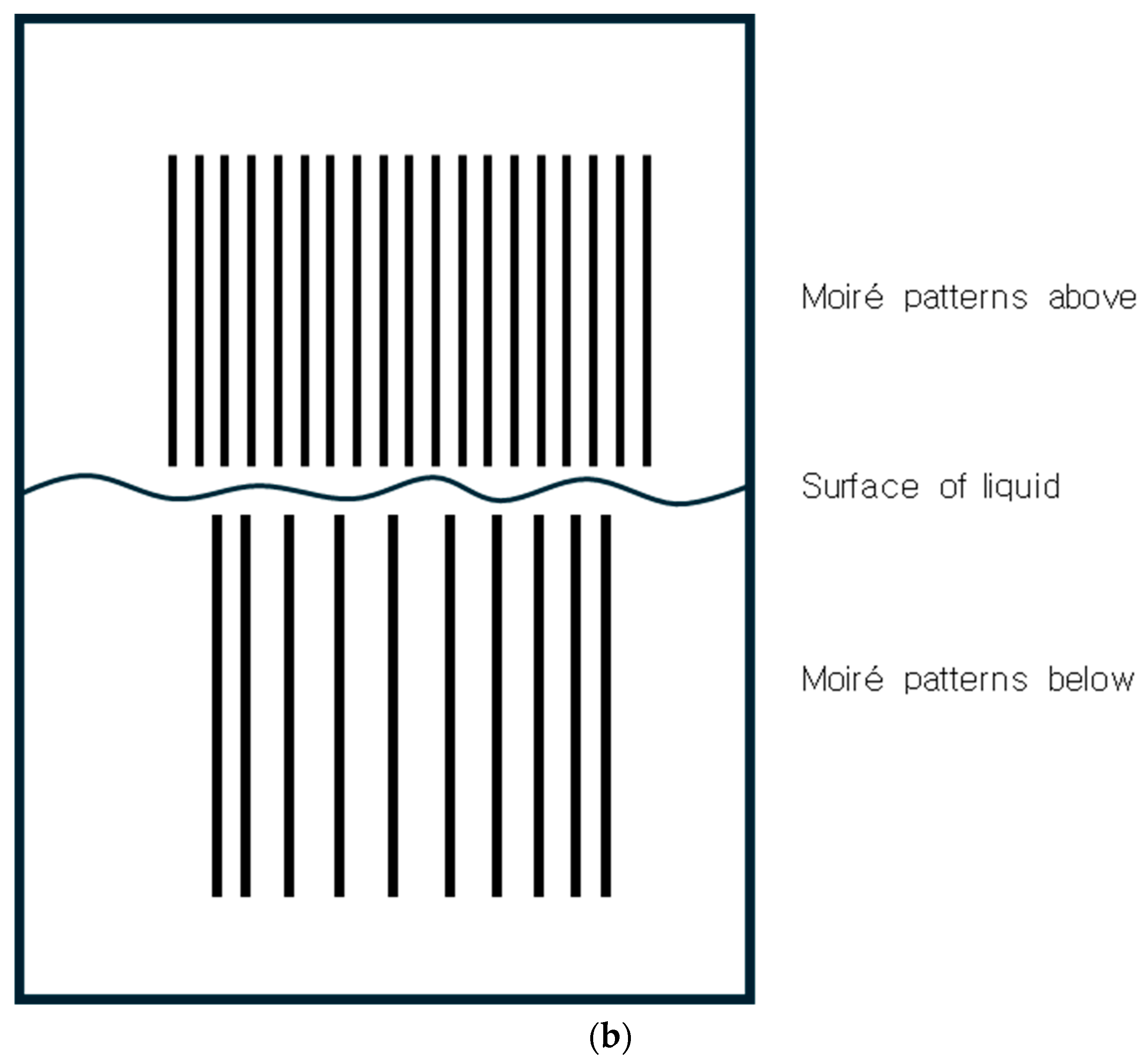

- (b)

- Non-parallel planes of a wedge (triangular prism) [20];

- (c)

- (d)

- Their combinations [36];

- (e)

- Multilayered volumetric structures (e.g., LED cubes) [37].

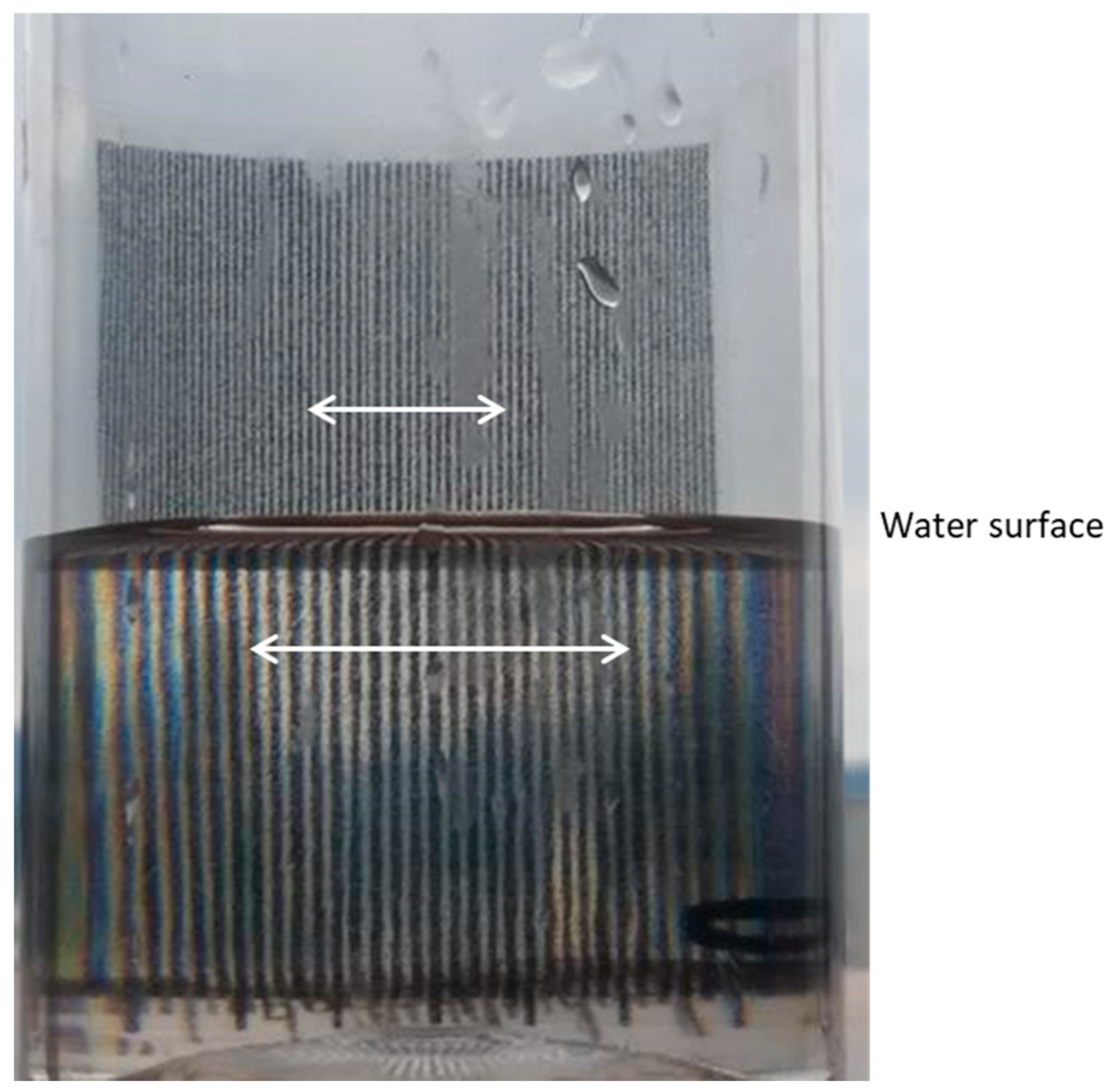

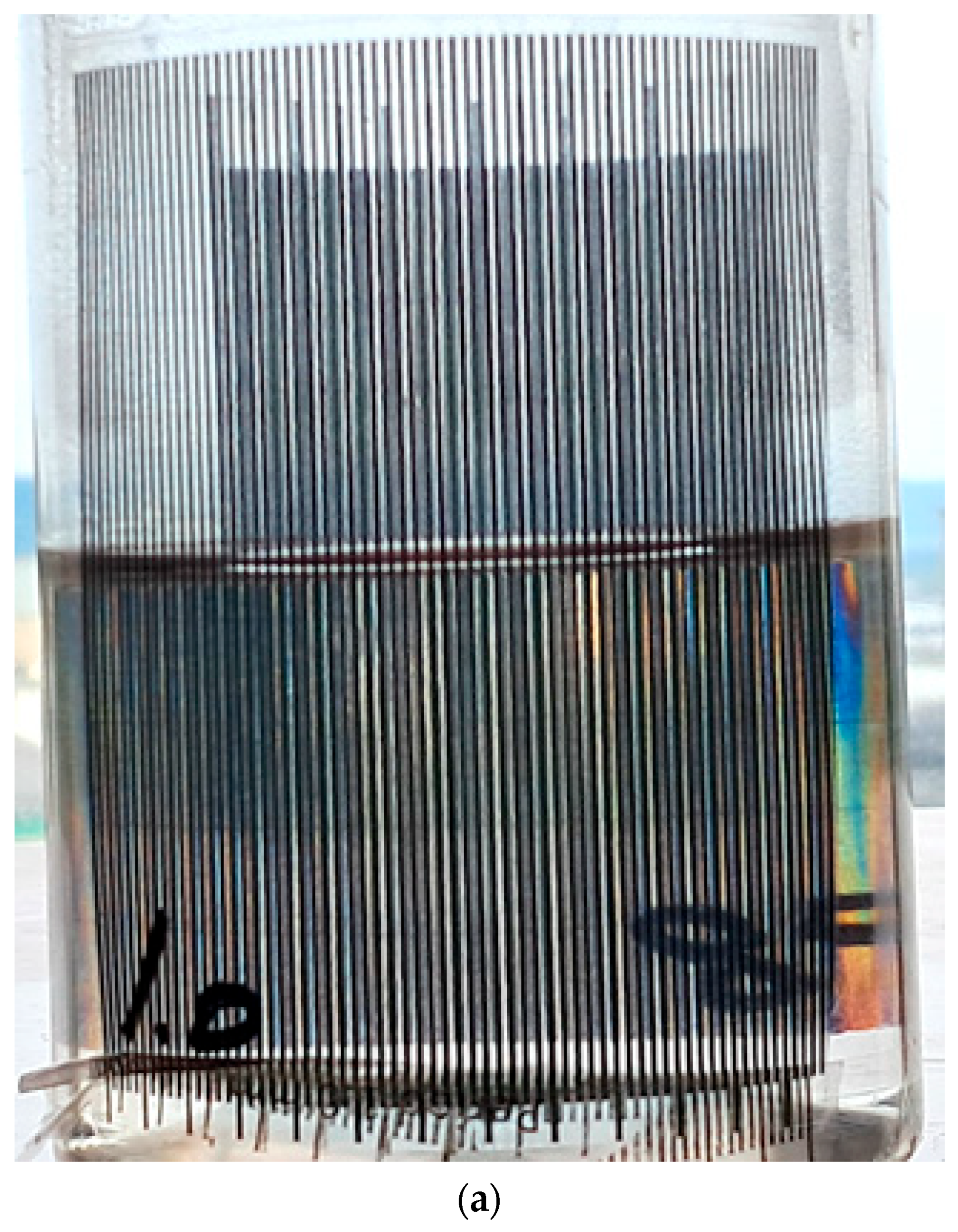

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

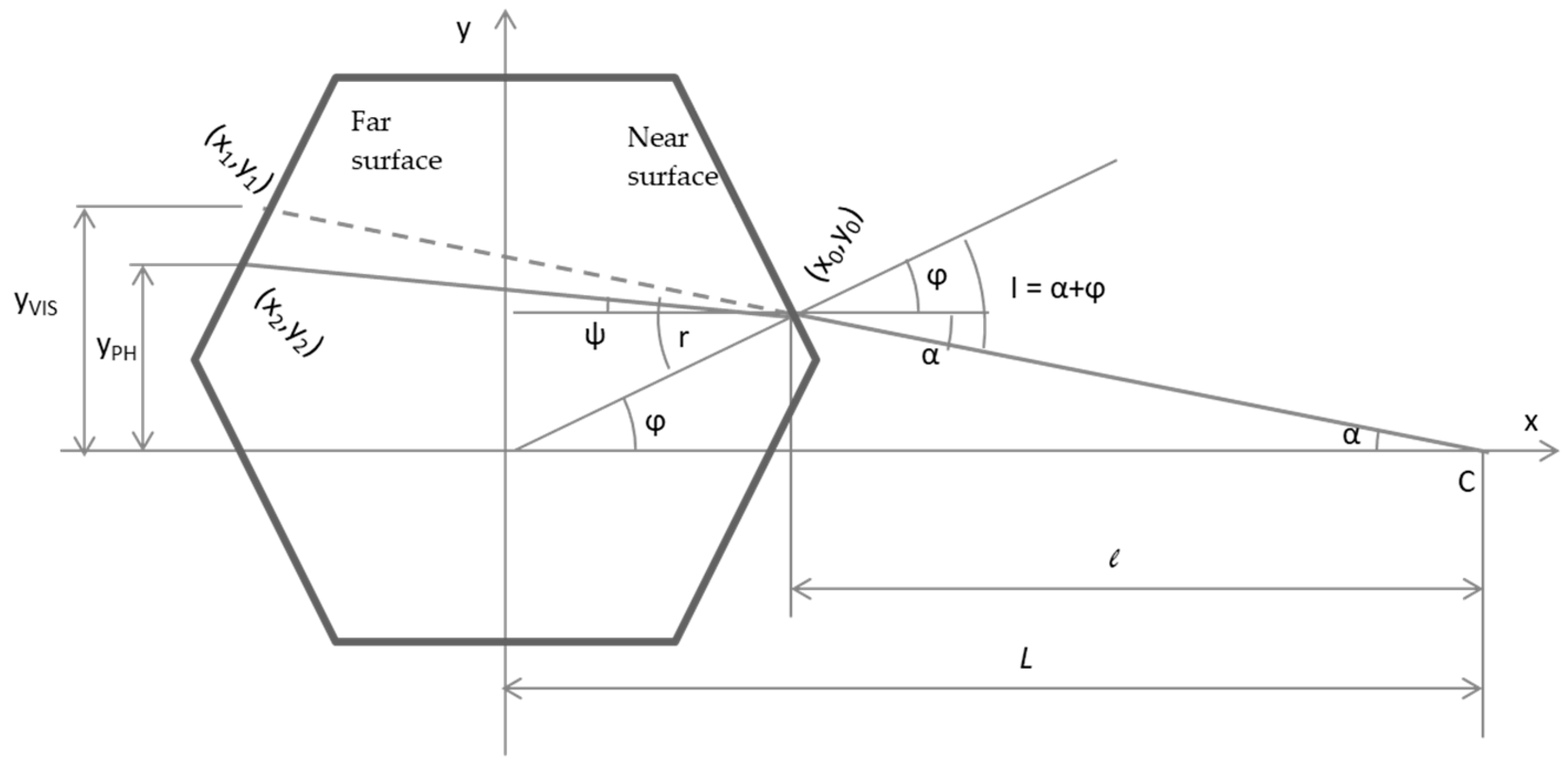

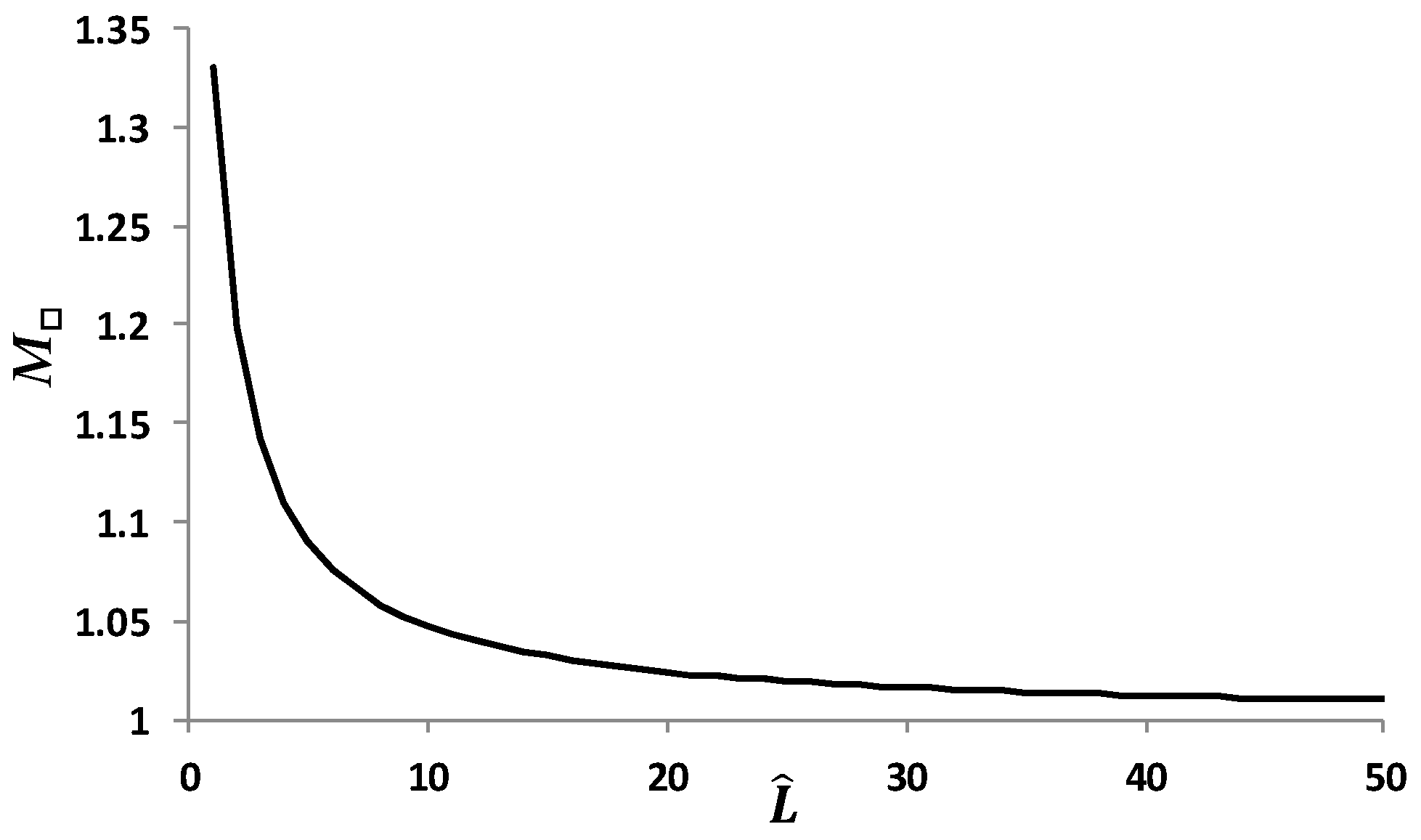

3.1. Refractive Magnification

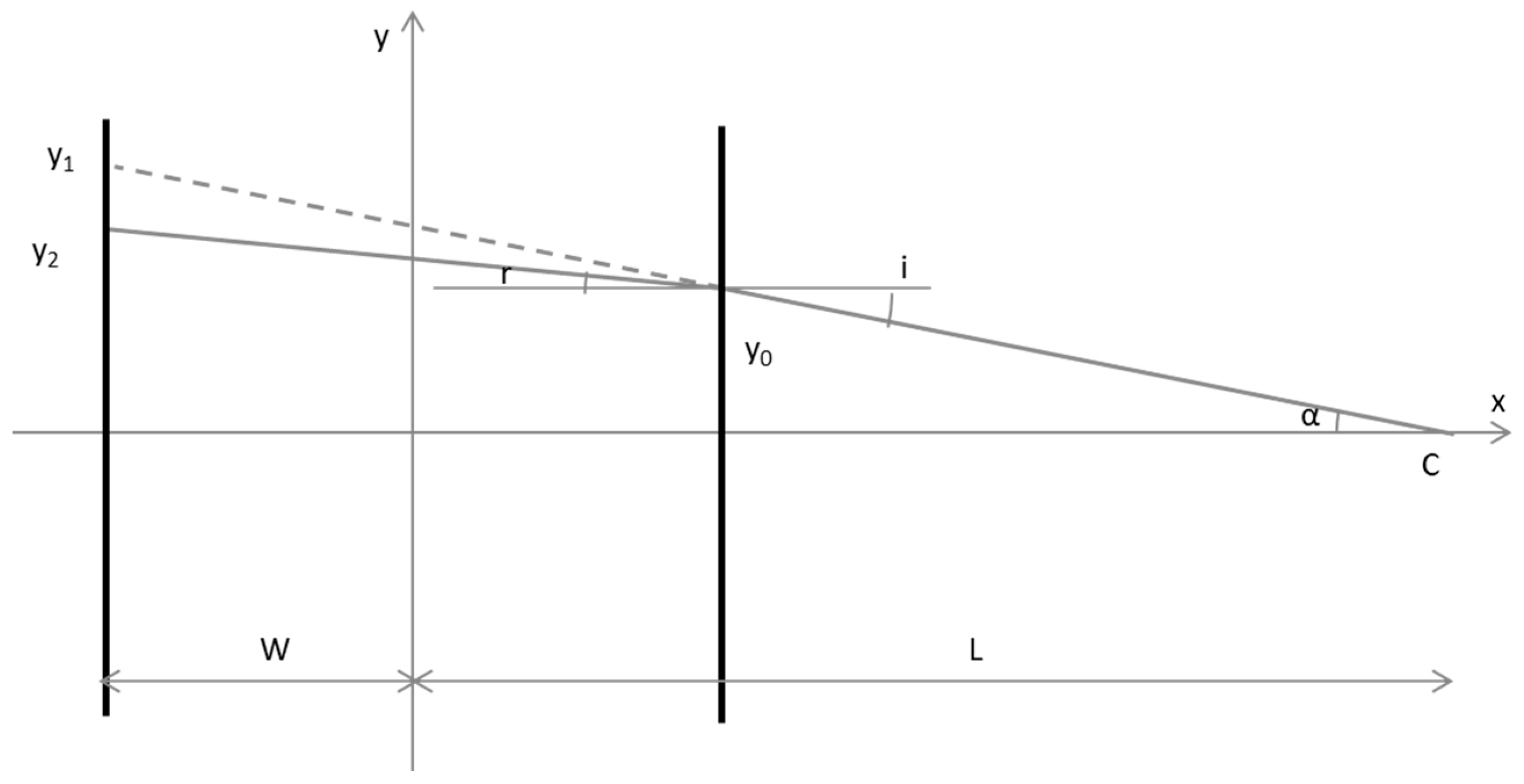

3.1.1. Refractive Magnification in a Parallelepiped

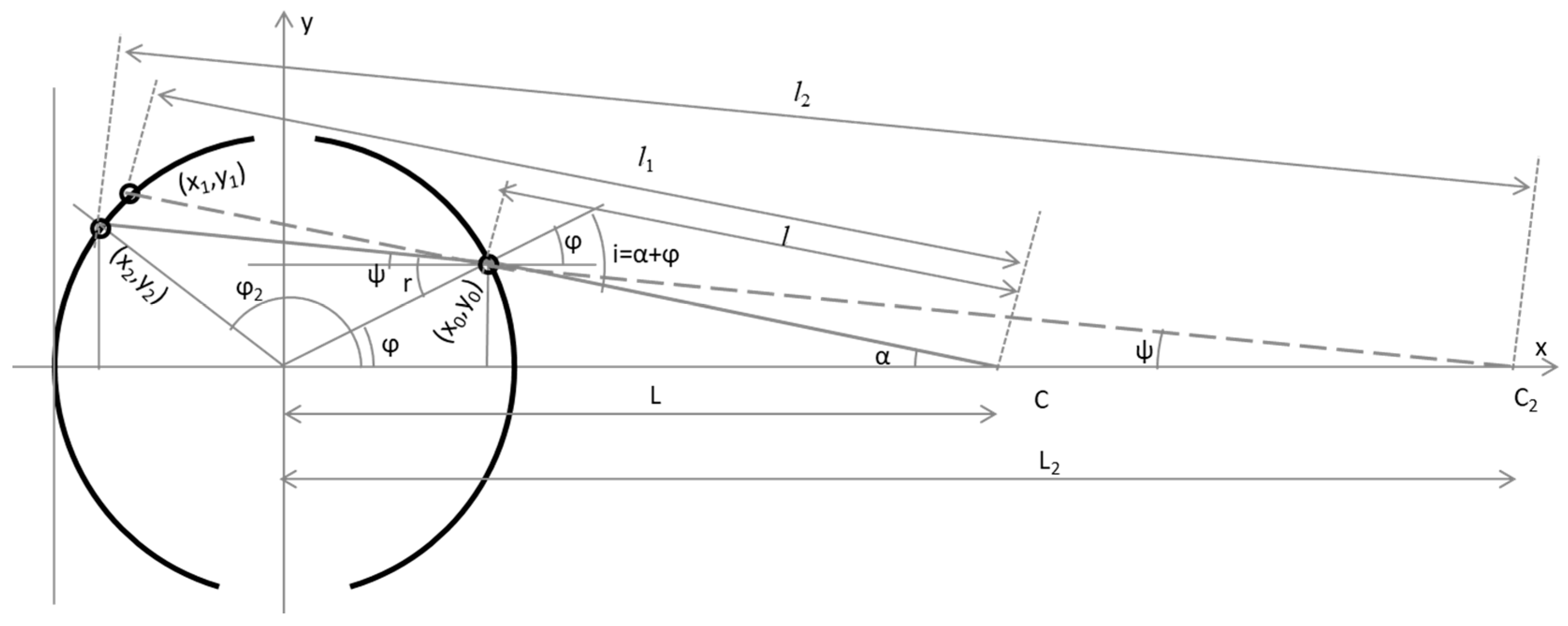

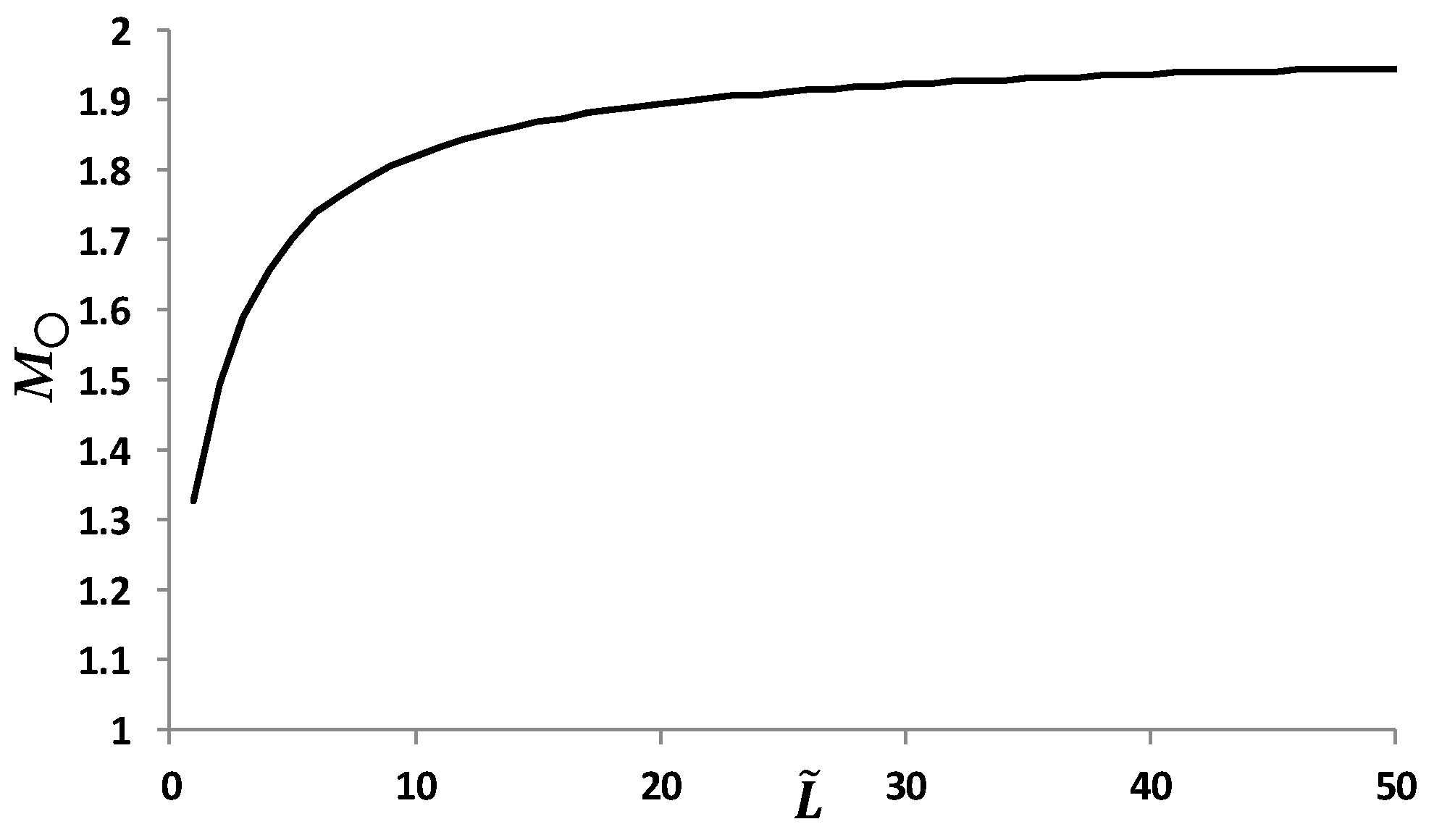

3.1.2. Refractive Magnification in a Cylinder

Near Surface

Far Surface

Formula for Refractive Magnification in a Cylinder

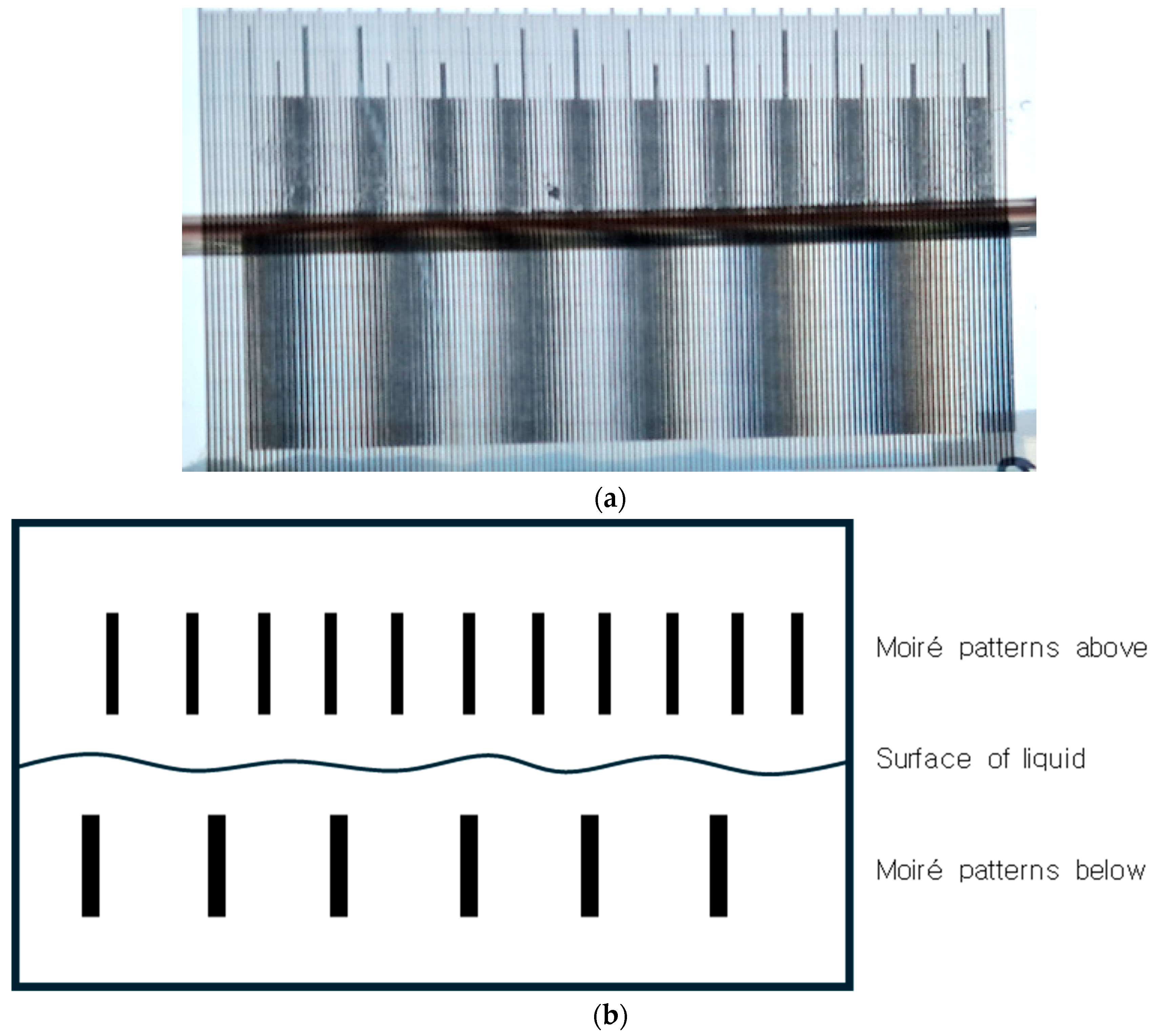

3.2. Moiré Effect

3.2.1. Moiré Effect in Parallelepiped

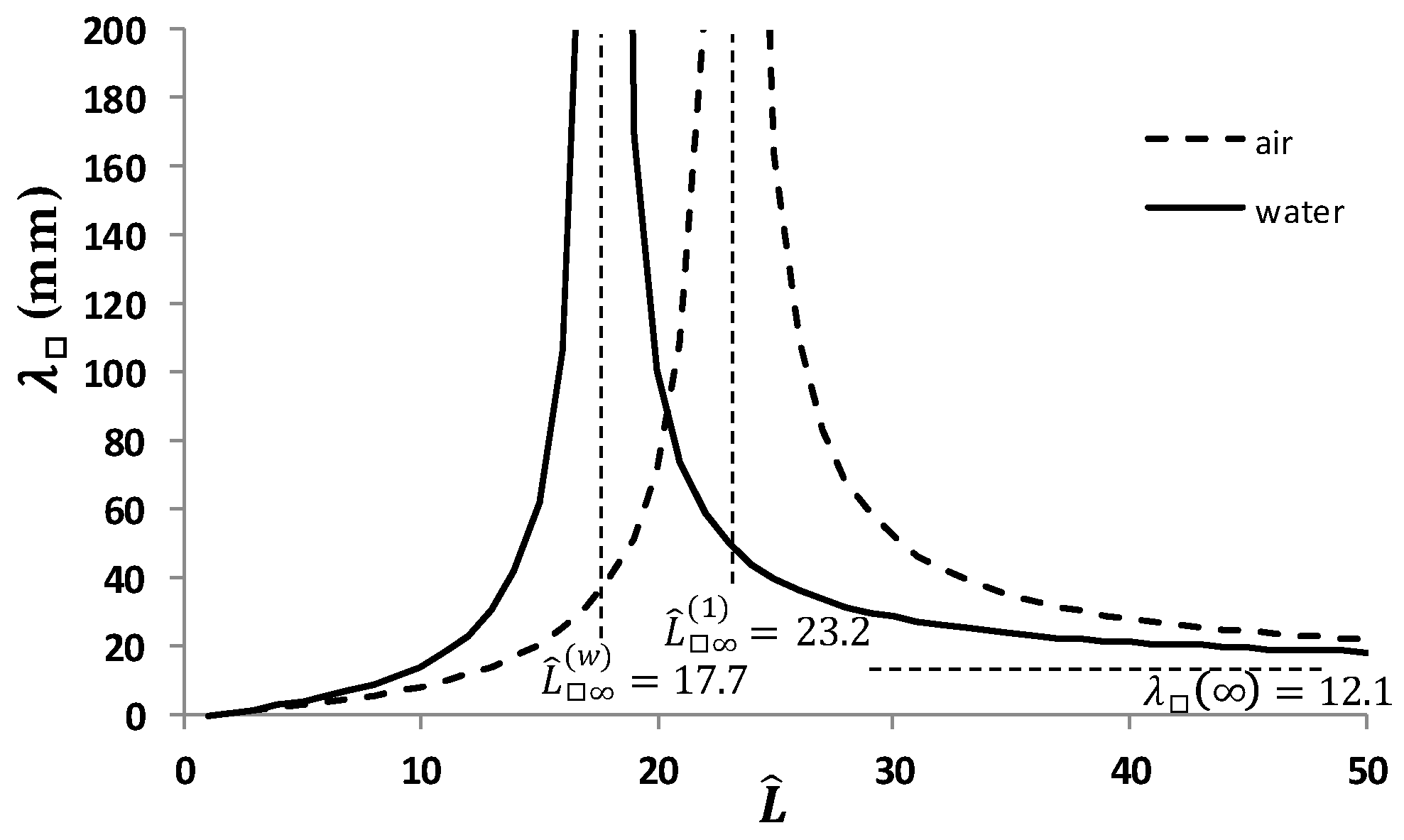

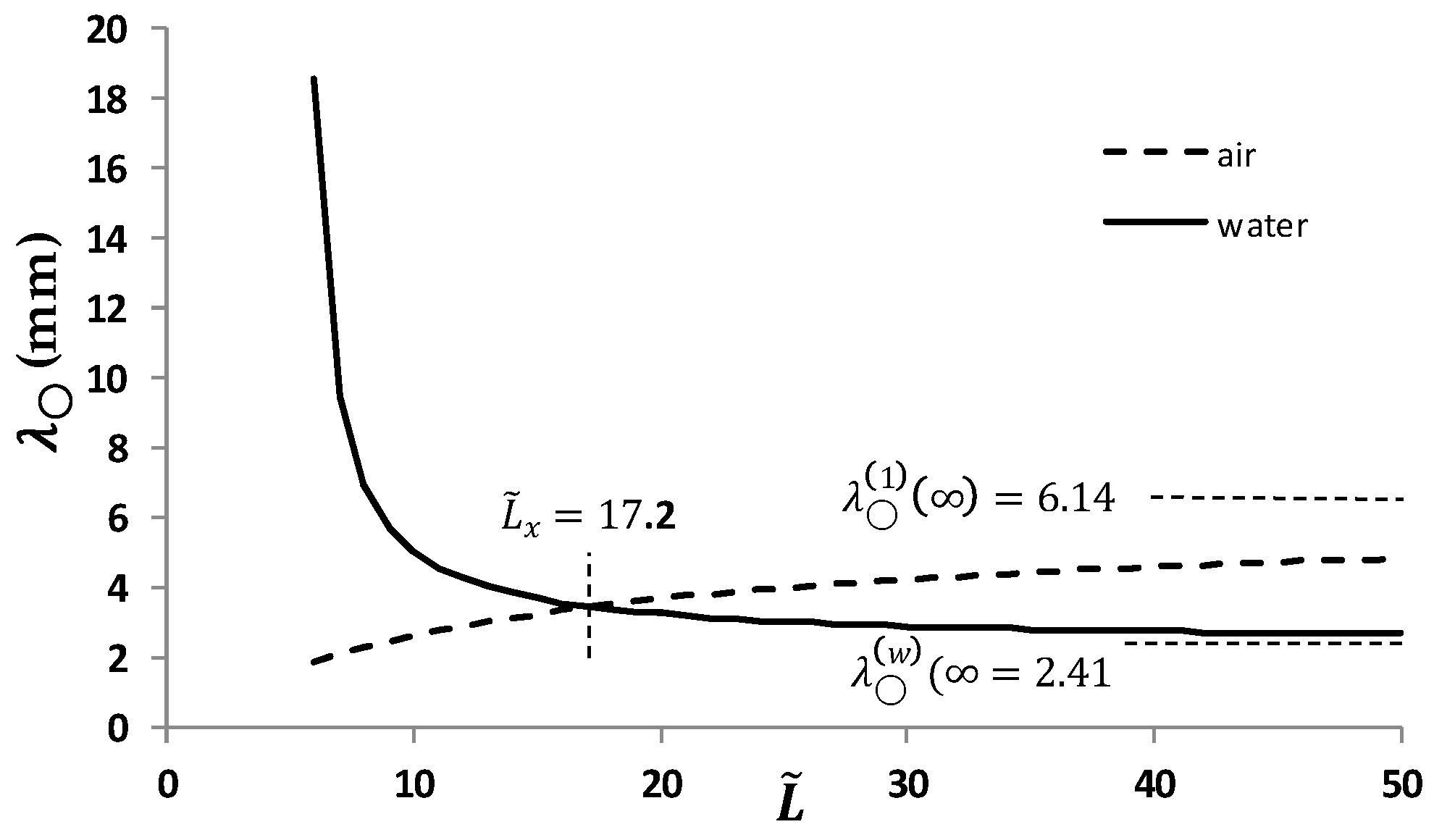

3.2.2. Moiré Effect in a Cylinder

3.3. Experiments

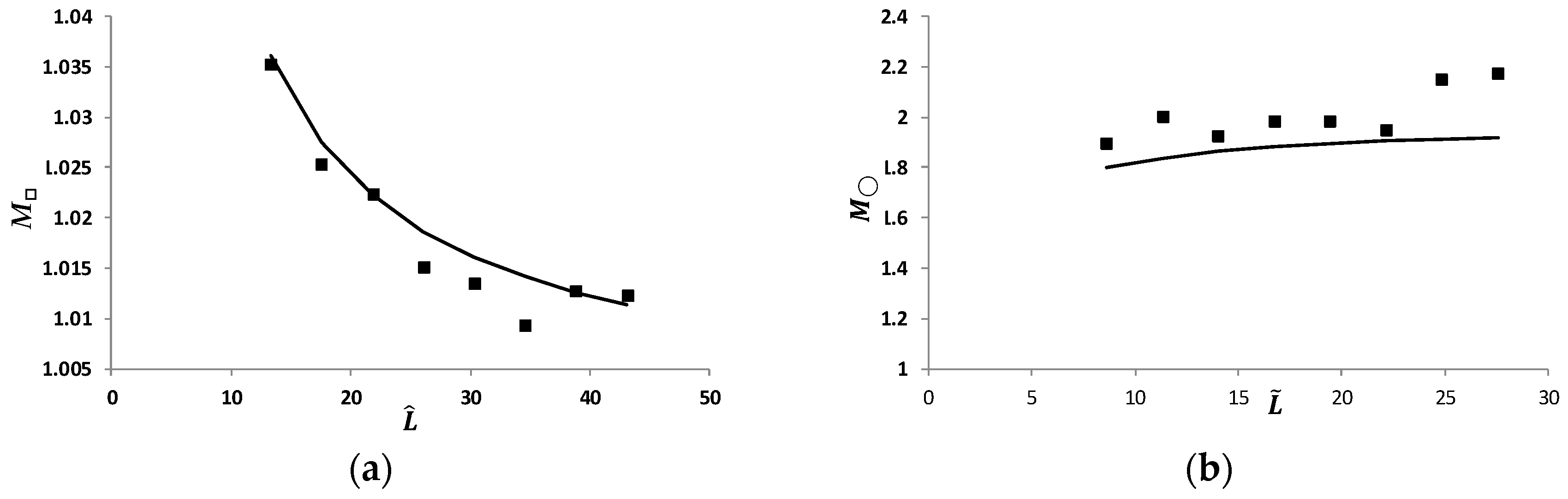

3.3.1. Experimental Refractive Magnification

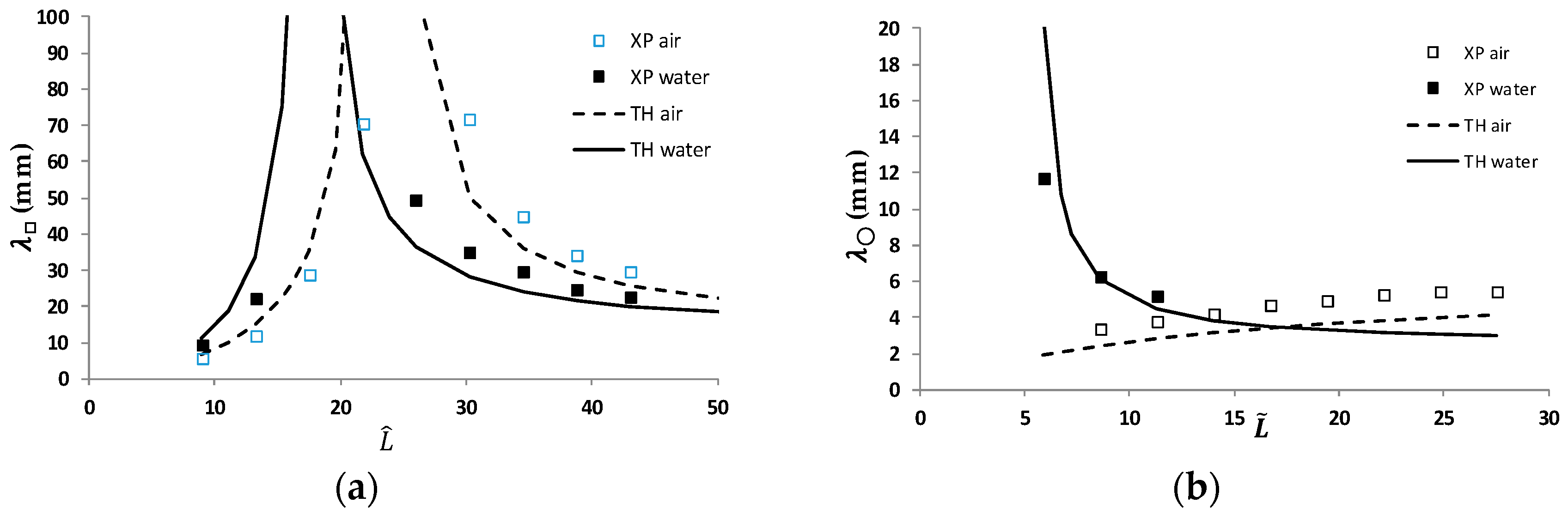

3.3.2. Experimental Moiré Period

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amidror, I. The Theory of the Moiré Phenomenon, Vol. I: Periodic Layers, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saveljev, V. The Geometry of the Moiré Effect in One, Two, and Three Dimensions; Cambridge Scholars: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saveljev, V. Various Grids in Moiré Measurements. Metrology 2024, 4, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciammarella, C.A. Basic optical law in the interpretation of moiré patterns applied to the analysis of strains. Exp. Mech. 1965, 5, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokozeki, S.; Kusaka, Y.; Patorski, K. Geometric parameters of moiré fringes. Appl. Opt. 1976, 15, 2223–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryngdahl, O. Moiré: Formation and interpretation. JOSA 1974, 64, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohnal, M. Moiré in a scanned image. Proc. SPIE 1999, 4016, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Van Winkle, M.; Bediakoa, D.K. Tuning interfacial chemistry with twistronics. Trends Chem. 2022, 4, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennighausen, Z.; Kar, S. Twistronics: A turning point in 2D quantum materials. Electron. Struct. 2021, 3, 014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, J.; Sun, M.; Cao, S. Emerging characteristics and properties of moiré materials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, R.K. Moiré patterns in nanomaterial. Mat. Sci. Semicon. Proc. 2022, 140, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, E.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Di Luca, M.; Maffione, G.; Hong, Y.; Farrar, L.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Mailly, D.; Charlier, J.-C.; et al. Non-identical moiré twins in bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, T.A.; Benschop, T.; Chen, X.; Krasovskii, E.E.; de Dood, M.J.A.; Tromp, R.M.; Allan, M.P.; van der Molen, S.J. Imaging moiré deformation and dynamics in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latychevskaia, T.; Escher, C.; Fink, H.-W. Moiré structures in twisted bilayer graphene studied by transmission electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 2019, 197, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luskin, M.; Wang, K. Review: Moiré-of-moiré superlattice in twisted trilayer graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 353001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Qi, D.; Schoelz, J.K.; Thompson, J.; Thibado, P.M.; Wheeler, V.D.; Nyakiti, L.O.; Myers-Ward, R.L.; Eddy, C.R., Jr.; Gaskill, D.K.; et al. Multilayer graphene, moiré patterns, grain boundaries and defects identified by scanning tunneling microscopy on the m-plane, non-polar surface of SiC. Carbon 2014, 80, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Kim, S.-K. Simulation of moiré effect in 3D displays. J. Opt. Soc. Korea 2010, 14, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Kim, S.-K. Simulation and measurement of moiré patterns at finite distance. Opt. Express 2011, 20, 2163–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciammarella, C.A.; Chiang, F.-P. Gap effect on moiré patterns. ZAMP 1968, 19, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Son, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.-G.; Heo, G. Moiré patterns in non-parallel surfaces such as prism. JOSA A 2020, 37, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saveljev, V.; Han, W.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Moiré effect in double-layered coaxial cylinders. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 5596–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Physical model of the moiré effect in cylindrical structures. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2017, 71, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V. Moiré effect in cylindrical objects. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2016, 68, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V. The off-axis moiré effect in double-layered cylinder. J. Mod. Opt. 2023, 70, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V. Moiré effect in 3D structures. In Advances in Optics: Reviews; Yurish, S.Y., Ed.; International Frequency Sensor Association Publishing: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sadan, M.B.; Houben, L.; Enyashin, A.N.; Seifert, G.; Tenne, R. Atom by atom: HRTEM insights into inorganic nanotubes and fullerene-like structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15643–15648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.H.; Young, N.P.; Kirkland, A.I.; Briggs, G.A.D. Resolving strain in carbon nanotubes at the atomic level. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenaga, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Koshino, M.; Sato, Y.; Urita, K.; Iijima, S. Imaging active topological defects in carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, G.; Craig, R.; Simmiss, T. Moiré interference in multilayered displays. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2007, 15, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, J. Moiré effect in displays: A tutorial. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 030803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xie, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Xia, M.; Luo, W.; Shi, Z. Moiré-induced band-gap opening in one-dimensional superlattices of carbon nanotubes on hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 115433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konevtsova, O.V.; Roshal, D.S.; Rochal, S.B. Moiré patterns and carbon nanotube sorting. Nano Futur. 2022, 6, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.F. TEM nano-moiré pattern analysis of a copper/single walled carbon nanotube nanocomposite synthesized by laser surface implanting. C-J. Carbon Res. 2018, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittemeier, N.; Verstraete, M.J.; Ordejon, P.; Zanolli, Z. Interference effects in one-dimensional moiré crystals. Carbon 2022, 186, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xu, Z.; Shang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Kauppinen, E.; Ding, F. Is there chiral correlation between graphitic layers in double-wall carbon nanotubes? Carbon 2019, 144, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveljev, V.; Heo, G. Moiré effect in combined planar and curved objects. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2024, 41, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saveljev, V. Moiré effect in multilayered 3D lattice. Appl. Opt. 2023, 62, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, Y.; Oster, G. Moiré patterns: Their application to refractive index and refractive index gradient measurements. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1964, 54, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karny, Z.; Kafri, O. Refractive-index measurements by moiré deflectometry. Appl. Opt. 1982, 21, 3326–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatt, L.; Livnat, A. Determination of the refractive index of a lens using moiré deflectometry. Appl. Opt. 1984, 23, 2241–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.M.; Kinney, J.A.S. Underwater Vision. Science 1970, 167, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfson, J.; Berghage, T. Perception and Performance under Water; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Shreeves, K. PADI Open Water Diver Manual; PADI: Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saveljev, V. Moiré Effect with Refraction. Photonics 2026, 13, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010047

Saveljev V. Moiré Effect with Refraction. Photonics. 2026; 13(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaveljev, Vladimir. 2026. "Moiré Effect with Refraction" Photonics 13, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010047

APA StyleSaveljev, V. (2026). Moiré Effect with Refraction. Photonics, 13(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010047