1. Introduction

Surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) are a special kind of electromagnetic mode existing at metal–dielectric interfaces, formed by the coupling between incident photons and the collective oscillations of free electrons in metals [

1,

2]. Such waves feature strong confinement at the metal surface and an exponential decay profile in the perpendicular direction [

3]. Benefiting from these attributes, SPPs can break the diffraction limit inherent to conventional optics and facilitate effective subwavelength optical confinement and manipulation [

4,

5,

6]. As a result, they demonstrate promising prospects for applications across nanophotonics, integrated optical circuits, and high-sensitivity sensing [

7,

8,

9].

Among the numerous waveguide structures that guide SPPs, metal–insulator–metal (MIM) waveguides have been extensively investigated owing to their compact structure, ease of fabrication and integration, and excellent field-localization capability [

6]. A typical MIM waveguide is formed by a thin dielectric layer sandwiched between two metal layers, creating a confined channel for light propagation. It can strongly confine electromagnetic energy in the nanoscale dielectric region, producing a significant field enhancement effect while maintaining a relatively long propagation distance [

10]. Based on MIM waveguides, researchers have successfully designed and implemented various functional nanophotonic devices, such as filters [

11], optical switches [

12,

13], couplers [

14], and various types of sensors [

3].

In MIM waveguide sensors, Fano resonance is regarded as an important physical mechanism for enhancing detection performance because of its highly asymmetric and steep spectral line shape [

15]. Fano resonances typically stem from the coherent interference between a localized narrowband state supported by a resonator and a broadband continuum state provided by a straight waveguide. This interference leads to a strongly asymmetric spectral feature in the transmission spectrum [

16]. Compared with symmetric Lorentzian resonances, the abrupt spectral variation at the Fano line edge is more sensitive to small perturbations in the ambient refractive index and can induce significant resonance wavelength shifts even for tiny refractive-index changes. Thus, Fano resonances provide an effective route for constructing high-precision refractive-index-sensitive structures.

In MIM waveguide systems, the key to effectively exciting and controlling Fano resonance lies in the geometric design of the resonator. In recent years, by introducing diverse resonator geometries, device performance has been continuously improved. For example, Zhu and Jin reported an elliptical split-ring resonator integrated with SiO

2 branches, which exhibited dual Fano resonances with a refractive index sensitivity of 1406.25 nm/RIU (refractive index unit, RIU) and a figure of merit (FOM) of 156.25 [

17]. By combining an inverted U-shaped rectangular split ring and a semicircular split ring, Sharmin et al. demonstrated a multi-resonator structure capable of generating quadruple Fano resonances, with a sensitivity up to 2400 nm/RIU and an FOM of 45.28 [

18]. Joy et al. designed a four-hand-shaped sector resonator that incorporated nanodots and waveguide stubs, yielding a highest sensitivity of 2470.48 nm/RIU alongside an FOM of 50.15 [

19]. These works indicate that, by finely tuning the resonator geometry and its coupling relation with the waveguide, high sensitivity and high FOM can be balanced to some extent.

Despite the significant progress achieved in previous studies, how to simultaneously realize high sensitivity and high FOM in a single structure remains a goal pursued in this field [

20]. The resonator geometry directly determines the distribution of the localized electromagnetic field and its coupling efficiency with the waveguide mode, thereby affecting the resonance line shape, loss, and detection limit. On this basis, this work proposes a novel ring–bridge–rounded square (RBS) resonator. The design aims to synergistically enhance the sensor performance by introducing two rounded square units at both sides of a traditional ring structure and an internal bridge-type structure. The rounded square units are mainly intended to enhance the magnetic-field convergence and thus improve the field-localization capability, whereas the bridge-type structure focuses on tuning the coupling strength and spectral line shape of the Fano resonance. Working together, these two elements significantly reinforce both the modal-interference effect and electromagnetic-field localization.

Comprehensive finite element method (FEM) simulations were conducted to explore the transmission spectra of the proposed architecture and to uncover the physical principles driving the Fano resonance. We also investigated the sensitivity of the device to variations in its geometric parameters. The simulation results confirm that the structure acts as a highly efficient sensor for refractive index changes, offering a remarkable sensitivity of 3268 nm/RIU and an FOM of 55.4. Additionally, its potential application in temperature sensing was investigated, proving its value in precision measurement fields. In summary, this paper proposes a practical and innovative design for realizing high-performance nanophotonic sensing devices.

2. Structural Design and Research Methods

2.1. Structural Model

In the present work, a two-dimensional (2D) simulation framework is adopted. This choice is justified because the thickness of the proposed structure greatly surpasses the penetration depth of surface plasmon polaritons, rendering the field variation along the thickness direction insignificant. Moreover, it has been reported in earlier studies that, under this condition, 2D calculations can reliably reproduce the magnetic-field distribution and transmission response of the analogous three-dimensional (3D) system [

21]. Therefore, the 2D approach allows a marked reduction in computational effort without sacrificing the accuracy or physical credibility of the numerical results.

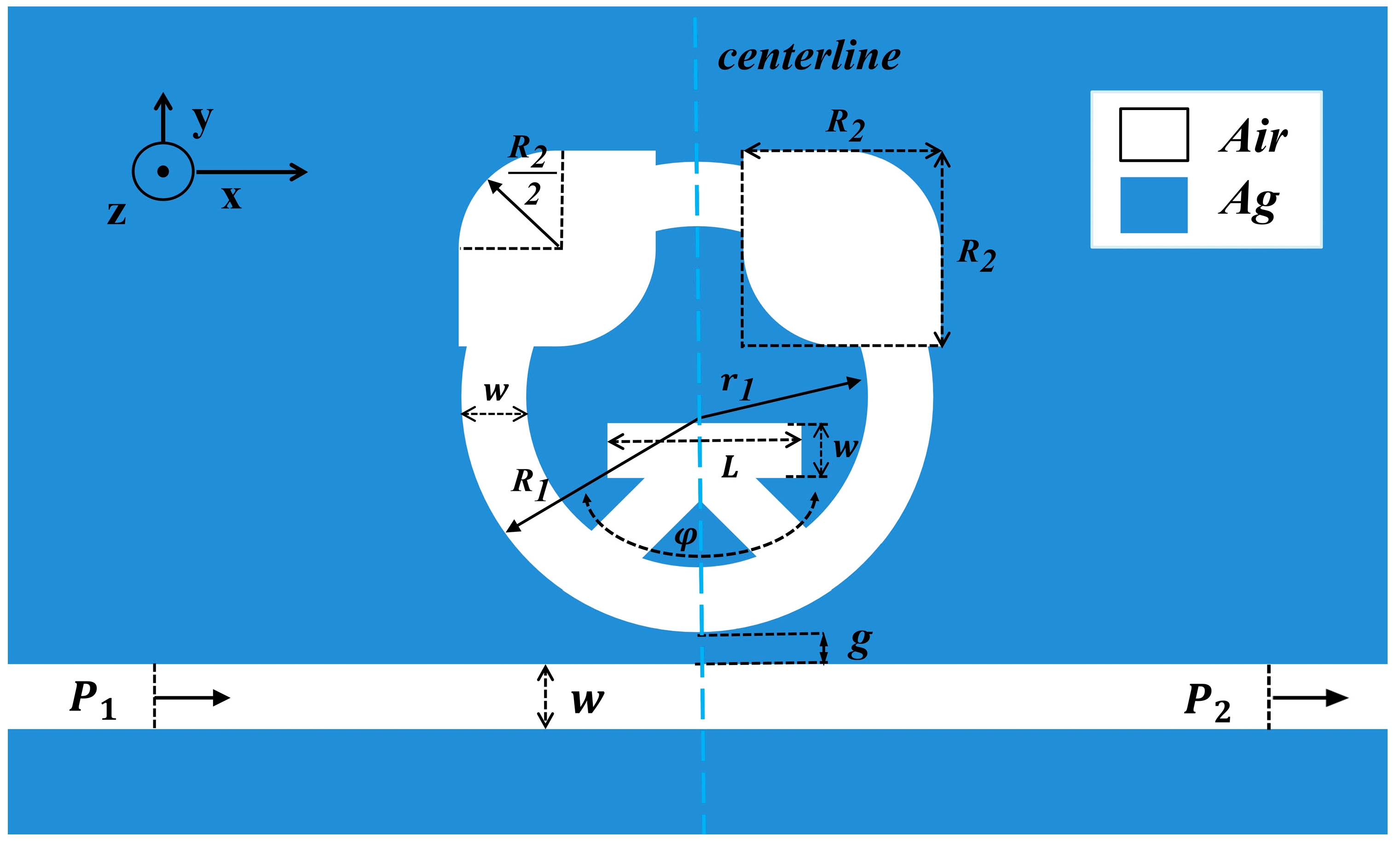

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the proposed two-dimensional sensor, which consists of a straight MIM waveguide side-coupled to an RBS resonator. The resonator body is an annular cavity. A rounded-square unit with two opposite rounded corners is arranged on each side of the ring, and a bridge-type element is incorporated inside the ring, where the subwavelength spacing between the bus waveguide and the resonator allows efficient coupling between the propagating mode in the waveguide and the localized resonance supported by the cavity.

As listed in

Table 1, the following key geometric parameters are defined in this work.

To ensure geometric consistency and simulation efficiency, specific constraints are applied. A uniform cavity wall thickness is maintained by setting the inner radius 50 nm smaller than the outer radius. The MIM waveguide shown in

Figure 1 has a width of

w = 50 nm; this dimension ensures the exclusive propagation of the fundamental even-symmetric surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode with low loss, while effectively cutting off high-er-order excitations. The corners of the square resonator are rounded using a fillet radius of

R2/2. The rotation angle

φ signifies the angular deviation between the ring’s vertical symmetry axis and the centerline linking the bridge and the ring centers, with clockwise rotation defined as positive. At

φ = 0°, the structure exhibits bilateral symmetry along the vertical axis.

In the schematic, P

1 and P

2 denote the input and output terminals, respectively. As depicted in

Figure 1, the blue areas represent silver (Ag), while the white zones indicate the dielectric medium. To investigate the fundamental sensing properties, air (relative permittivity = 1) is selected as the filling dielectric.

2.2. Theoretical Model and Materials

SPP excitation and propagation are supported by a transverse-magnetic (TM) mode, with its magnetic field perpendicular to the propagation direction within the interface. In this work, the dispersion relation of the TM mode in the MIM waveguide is governed by the following equation [

22,

23,

24]:

where

k is the wave vector in the waveguide,

w is the waveguide width,

is the ratio of the permittivity of the dielectric and metal, and

is the attenuation constant. Here,

is the free space wave vector, and

and

are the permittivity of the dielectric and metal, respectively.

The permittivity

of the metal (silver) exhibits a pronounced dependence on frequency. To accurately describe the optical response of silver in the near-infrared band, the classical Debye–Drude dispersion model is adopted [

25,

26]:

The model parameters for silver are summarized in

Table 2.

2.3. Simulation Setup and Performance Metrics

Numerical analysis of the proposed sensor structure was conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.4a.

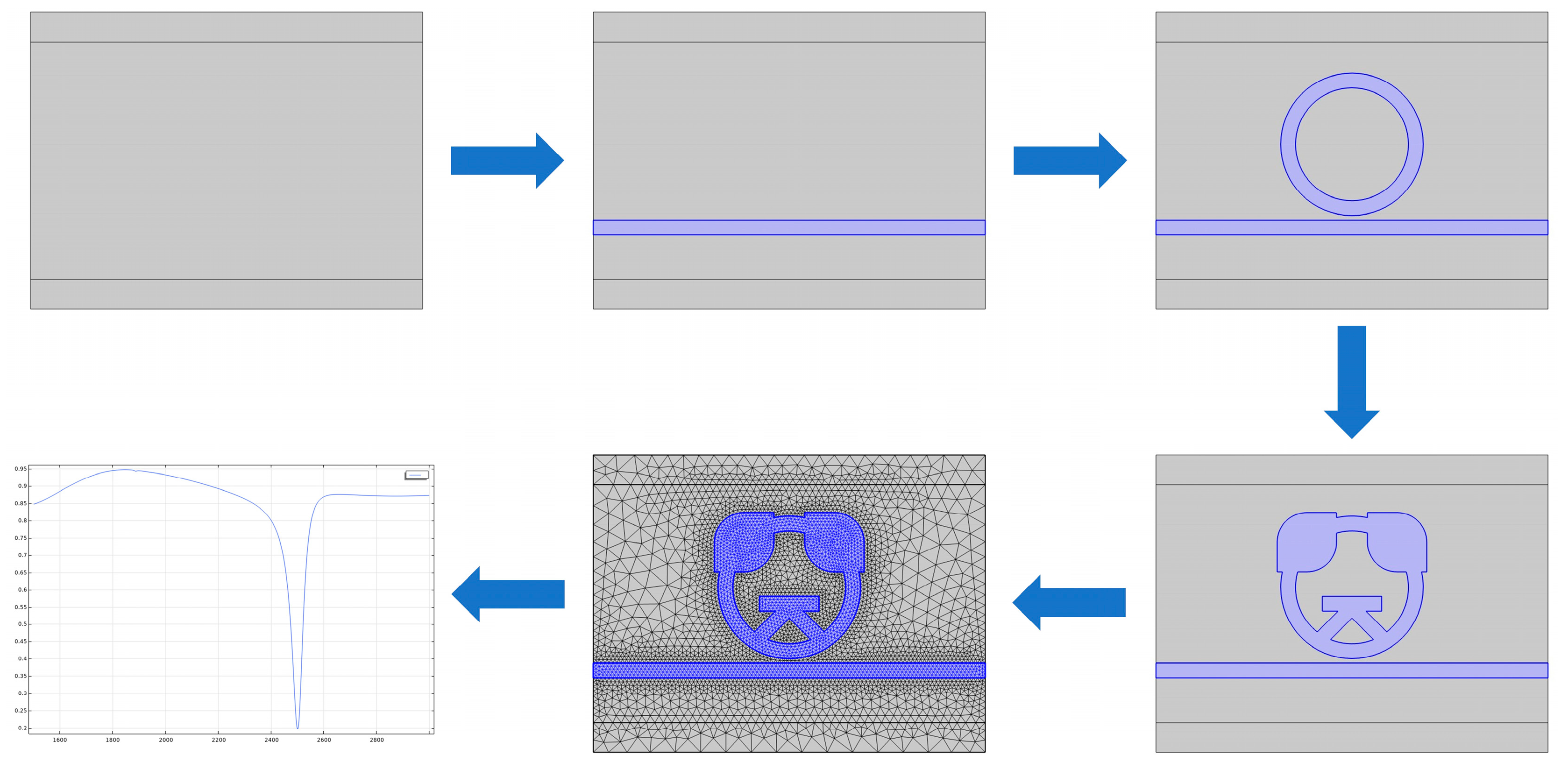

Figure 2 outlines the specific simulation flow, which mainly includes the following steps.

In COMSOL Multiphysics 5.4a, the two-dimensional geometric model shown in

Figure 1 is established using the built-in geometric tools.

Appropriate material parameters are assigned to each region. The dielectric properties of silver are described by the Debye–Drude dispersion model (Equation (2)) to accurately characterize its optical response in the near-infrared band, while the dielectric region is set as air with a relative permittivity of 1.

In the physics and boundary-condition settings, the left port (P1) is defined as the input port, where a 1 W fundamental TM mode is excited. The right port (P2) is set as the output port with the excitation source turned off. All external boundaries of the model are set as perfectly matched layers (PMLs) to simulate open boundary conditions and accurately capture the eigenmodes of the structure.

Considering the field distribution characteristics in different regions, a non-uniform meshing strategy is adopted. A denser triangular mesh is used in the waveguide–resonator coupling region and inside the resonator, where the electromagnetic field gradient changes sharply, whereas a coarser mesh is used in regions with slowly varying field intensity. This mesh configuration ensures sufficient accuracy in key regions while effectively improving computational efficiency [

28].

Frequency-domain simulations were performed by sweeping the excitation wavelength from 1500 to 4600 nm in 1 nm increments. This procedure generates the transmission profile, denoted as T(λ). From T(λ), critical metrics for assessing sensing capabilities are extracted, namely the resonance wavelength and the full width at half maximum (FWHM). Given the asymmetric line shape of the Fano resonance, the FWHM was determined by measuring the spectral width at a transmission level defined as the arithmetic mean of the maximum transmittance in the spectrum and the minimum transmittance at the resonance dip. Based on these extracted parameters, the sensor’s performance is primarily quantified using two fundamental indicators, sensitivity and Figure of Merit.

Sensitivity (S): This parameter describes the responsiveness of the device and is calculated as the ratio of the resonance wavelength displacement to the variation in the ambient refractive index [

29]:

Here, Δλ represents the shift in the resonance dip, while Δn denotes the change in the environment’s refractive index (measured in RIU).

Figure of Merit (FOM): The FOM serves as a comprehensive metric that balances sensitivity against spectral selectivity. It is mathematically expressed as the sensitivity divided by the FWHM of the resonance mode [

29,

30]:

The FOM reflects the sensitivity and spectral sharpness of the device in a comprehensive manner. A high FOM indicates that the sensor can both resolve minute refractive-index changes and maintain good resonance selectivity and signal-to-noise ratio [

31].

3. Simulation Results and Analysis

3.1. Generation and Mechanism of Fano Resonance

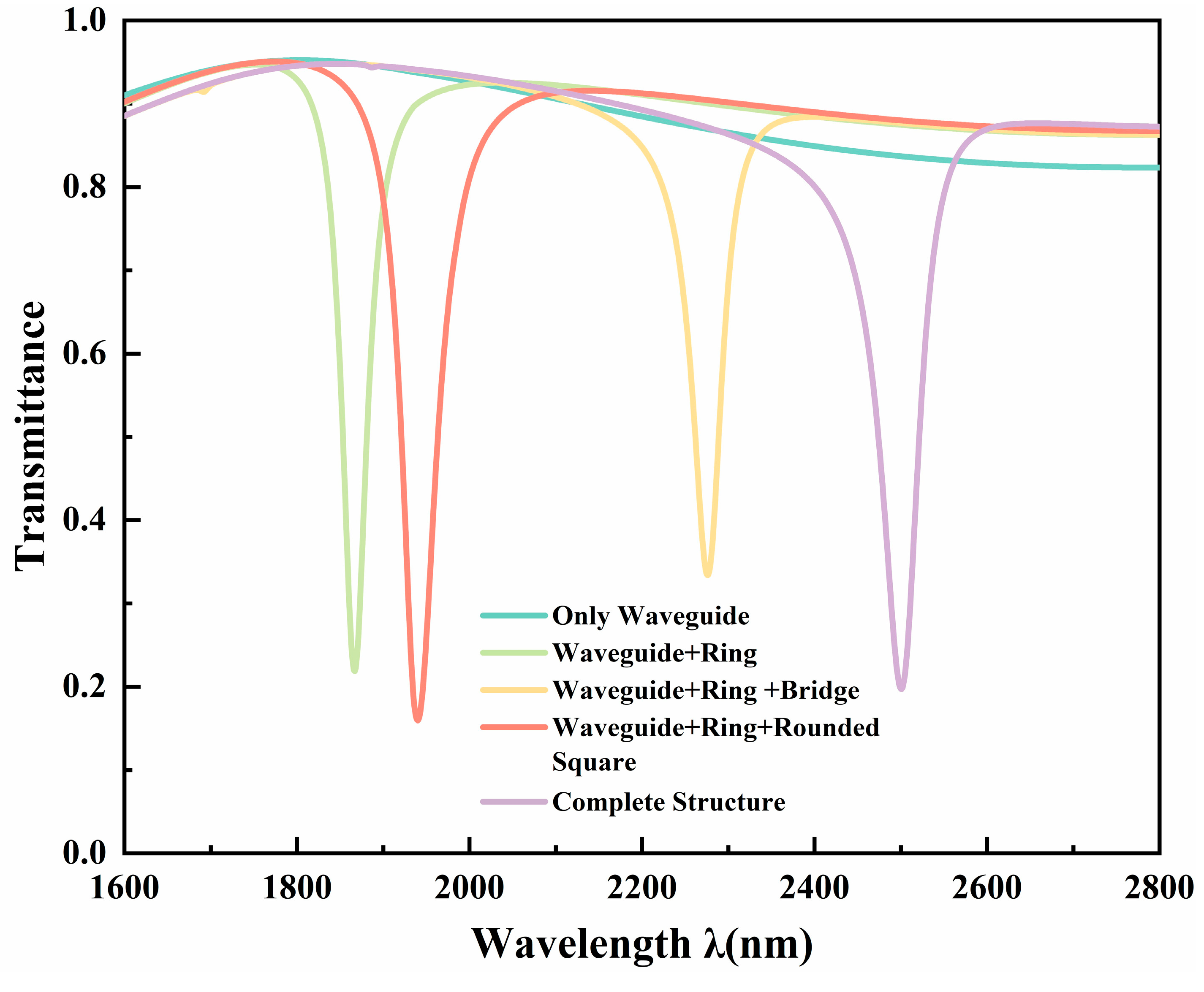

In order to reveal the underlying mechanism generating the Fano resonance, we investigated the transmission characteristics of five specific geometric configurations. These include the fundamental MIM waveguide and the waveguide coupled to four different resonator variations: a standard single ring, a ring containing an inner bridge, a ring flanked by rounded square cavities, and the final proposed RBS architecture.

Figure 3 presents the transmission spectra for these setups.

For the structure containing only the straight MIM waveguide, the transmittance remains at a high level (approximately 0.8–0.95) over the entire simulation wavelength range, and can be treated as a broadband continuum state. For the other four coupled structures, distinct resonance dips and asymmetric spectral profiles appear, indicating that Fano resonances are successfully excited between them and the MIM waveguide [

7].

Further analysis reveals that the internal bridge structure and the added rounded squares have different impacts on the resonance behavior. The former significantly enhances the magnetic-field localization and coupling strength, whereas the latter effectively reduces the transmittance at the resonance dip and induces a redshift of the resonance wavelength. The transmission spectrum of the complete RBS structure combines the advantages of the above two structures: it maintains a low transmittance while achieving a longer resonance wavelength and exhibits a typical asymmetric Fano line shape, indicating strong destructive interference between the continuum state and the discrete state.

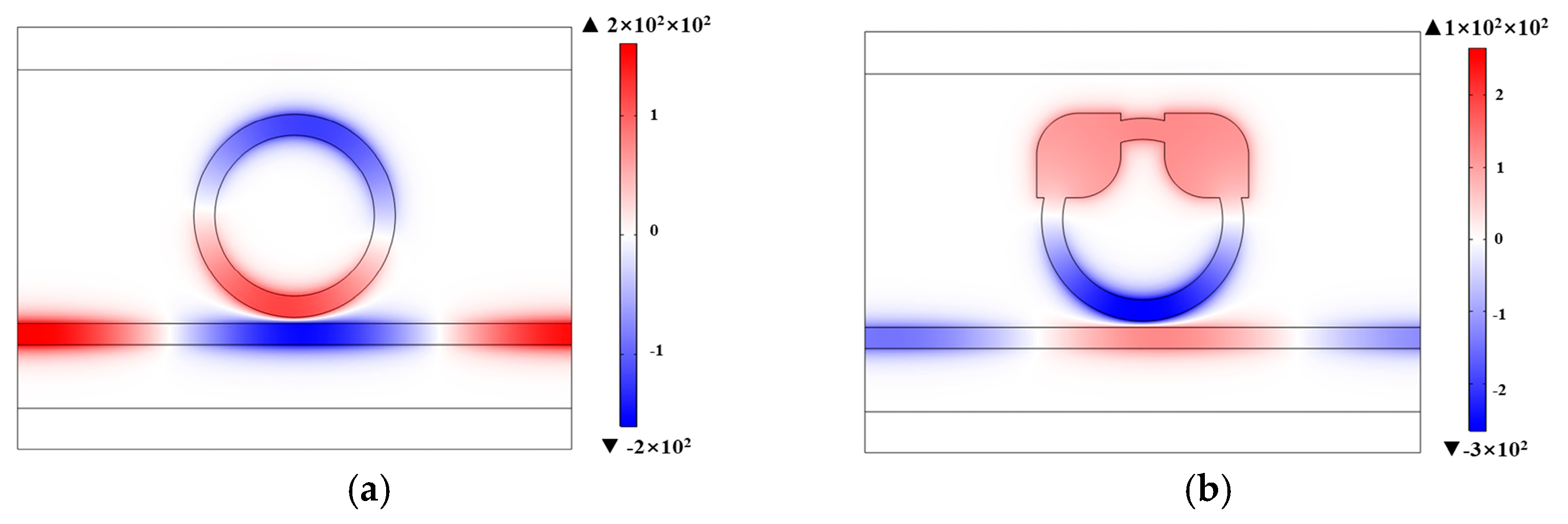

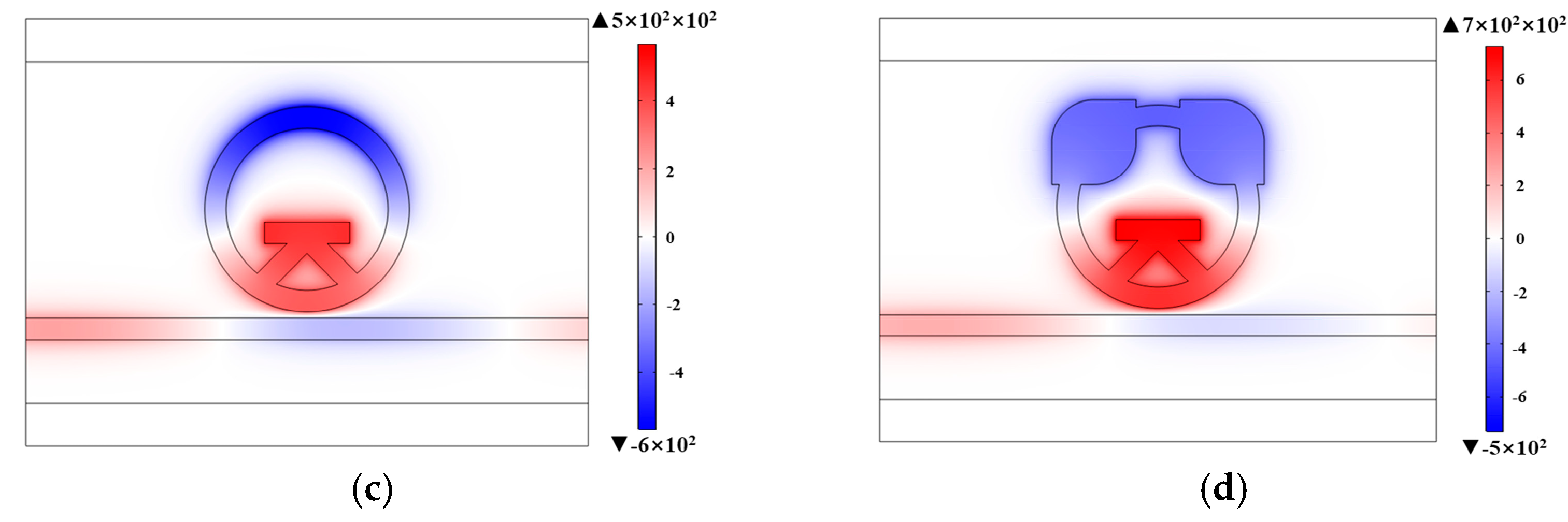

To further elucidate the resonance mechanism, normalized magnetic-field distributions of four structures at their respective resonance wavelengths are plotted in

Figure 4. The ring resonator facilitates effective coupling and confinement of SPP energy in all configurations. Additionally, the magnetic fields in its upper and lower segments are clearly out of phase.

Figure 4a shows that the magnetic field in the sole ring resonator structure is primarily confined to its upper and lower sides, retaining a clear out-of-phase profile despite its relatively low overall intensity. For this configuration, the obtained refractive-index sensitivity corresponds to approximately 2320 nm/RIU.

Figure 4b shows that after introducing the rounded square units, the local geometric protrusions enhance the magnetic-field convergence and energy coupling, confining more energy in the cavity and increasing the sensitivity to about 2620 nm/RIU.

Figure 4c shows that introducing solely the bridge structure further enhances the intracavity magnetic field and the coupling strength. This leads to a more pronounced Fano resonance, which raises the sensitivity to 3080 nm/RIU. Nevertheless, substantial transmission persists in the straight waveguide, resulting in a relatively high transmittance at the resonance dip.

In

Figure 4d, for the complete RBS structure, the magnetic field is mainly concentrated inside the resonator, and the energy in the waveguide is minimal. The cooperative effect of the bridge structure and rounded squares significantly enhances the Fano-resonance strength, and the sensitivity reaches as high as 3268 nm/RIU. It can be seen that the complete RBS structure combines the advantages of the ring resonator with rounded square units and the ring resonator with an internal bridge, leading to a remarkable enhancement of both the modal-interference effect and electromagnetic-field localization. This explains why the RBS resonator can simultaneously achieve high sensitivity and a relatively high FOM.

3.2. Optimization of Geometric Parameters

The sensor’s performance is highly sensitive to its geometric parameters. Therefore, our analysis focuses on the impact of five key design variables: the outer radius of the ring R1, coupling distance g, rotation angle of the bridge structure φ, side length of the rounded square R2, and length of the upper part of the bridge L on the Fano resonance and sensing performance. While keeping the waveguide width fixed at w = 50 nm, the initial parameters of the RBS resonator were set as R1 = 240 nm, r1 = R1 – 50 = 190 nm, R2 = 200 nm, φ = 0°, L = 200 nm, and g = 15 nm.

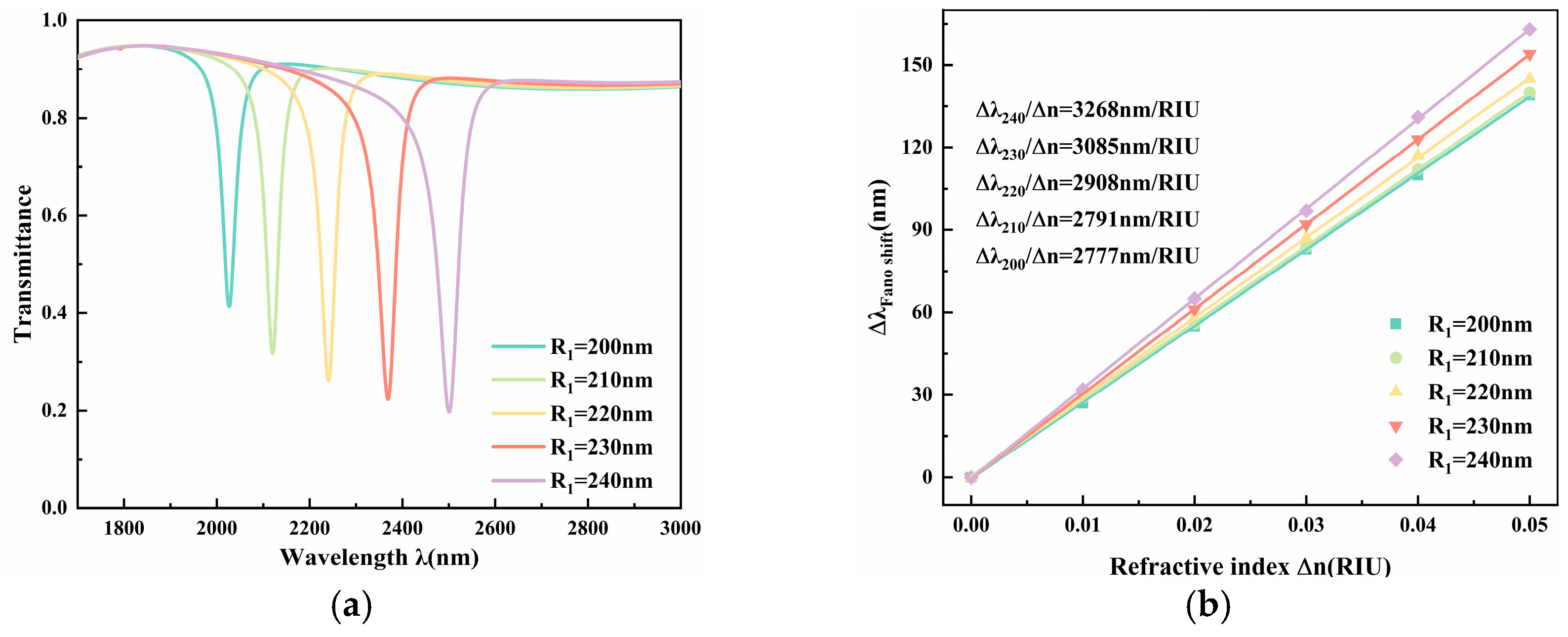

3.2.1. Influence of R1

To investigate how the resonator dimensions affect performance, the outer radius

R1 was adjusted within the range of 200–240 nm at 10 nm intervals, while maintaining other geometric parameters constant. The corresponding transmission spectra are presented in

Figure 5a. An increase in

R1 extends the effective optical path length inside the cavity, resulting in a distinct redshift of the resonance mode. Simultaneously, this geometric expansion leads to a deeper transmittance dip and a narrower FWHM, thereby significantly improving the FOM.

By linearly fitting the resonance wavelengths under different refractive indices [

Figure 5b], the sensitivity exhibits a positive correlation with

R1, rising from 2777 nm/RIU to 3268 nm/RIU, showing that increasing the ring size appropriately helps to improve the refractive-index response. In practical device design,

R1 can be determined by comprehensively considering the target sensitivity and size constraints. To obtain excellent sensitivity and FOM simultaneously,

R1 = 240 nm is adopted in this paper.

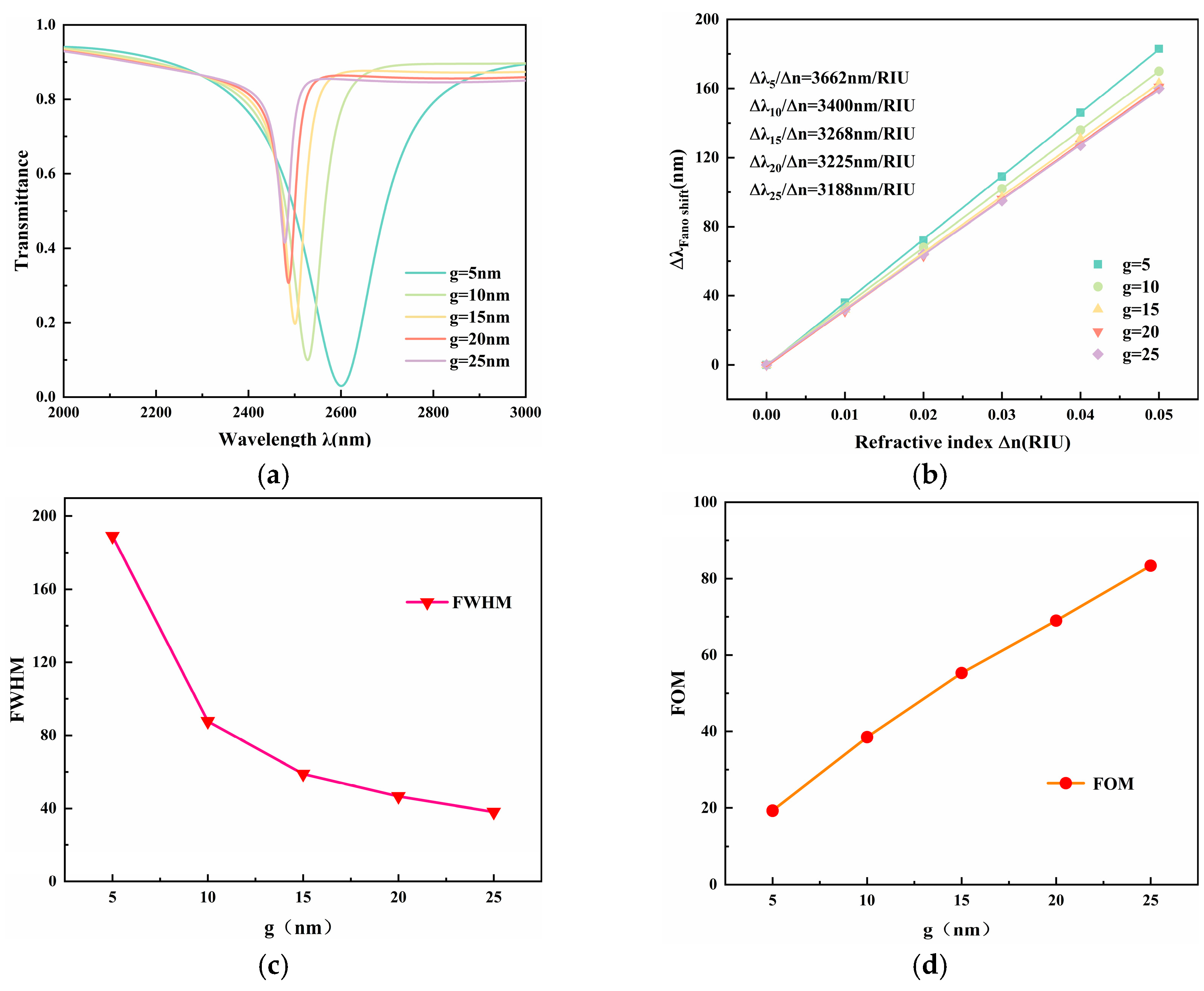

3.2.2. Influence of g

The coupling distance

g is an important structural parameter that changes the energy-exchange efficiency between the resonator and the waveguide mode. To systematically evaluate its influence,

g was increased from 5 nm to 25 nm. The corresponding changes in transmission characteristics and sensing performance are shown in

Figure 6.

As seen in

Figure 6a, with increasing

g, the transmission spectra exhibit three main trends: the resonance dip undergoes a blueshift, the transmittance at the dip increases significantly, and the linewidth of the resonance dip becomes markedly narrower. These phenomena indicate that the coupling strength between the waveguide and RBS resonator weakens as

g increases. Consequently, more energy passes directly through the waveguide without being effectively coupled into the resonator, and the magnetic-field localization in the cavity is greatly reduced.

The fitted sensitivity curves in

Figure 6b show that the sensitivity varies slowly between 3188 and 3662 nm/RIU and shows low dependence on

g. In contrast, the FWHM decreases significantly with increasing

g [

Figure 6c], causing the FOM to rise rapidly from 17.48 to 85.76 [

Figure 6d]. It should be noted that at the extreme lower end of this range (e.g.,

g = 5 nm), the classical local-response model used here may approach its limit of validity, as non-local or quantum effects could become non-negligible. The data at

g = 5 nm are included primarily to illustrate the continuous trend of performance versus gap size. Although a narrower linewidth is beneficial for improving the FOM, an excessively large coupling distance (e.g.,

g = 20 nm and

g = 25 nm) leads to excessively high transmittance at the resonance dip, indicating overly weak coupling, which is unfavorable for practical sensing applications.

By comprehensively considering sensitivity, resonance depth and FOM, g = 15 nm is chosen as the best-performing compromise in this work.

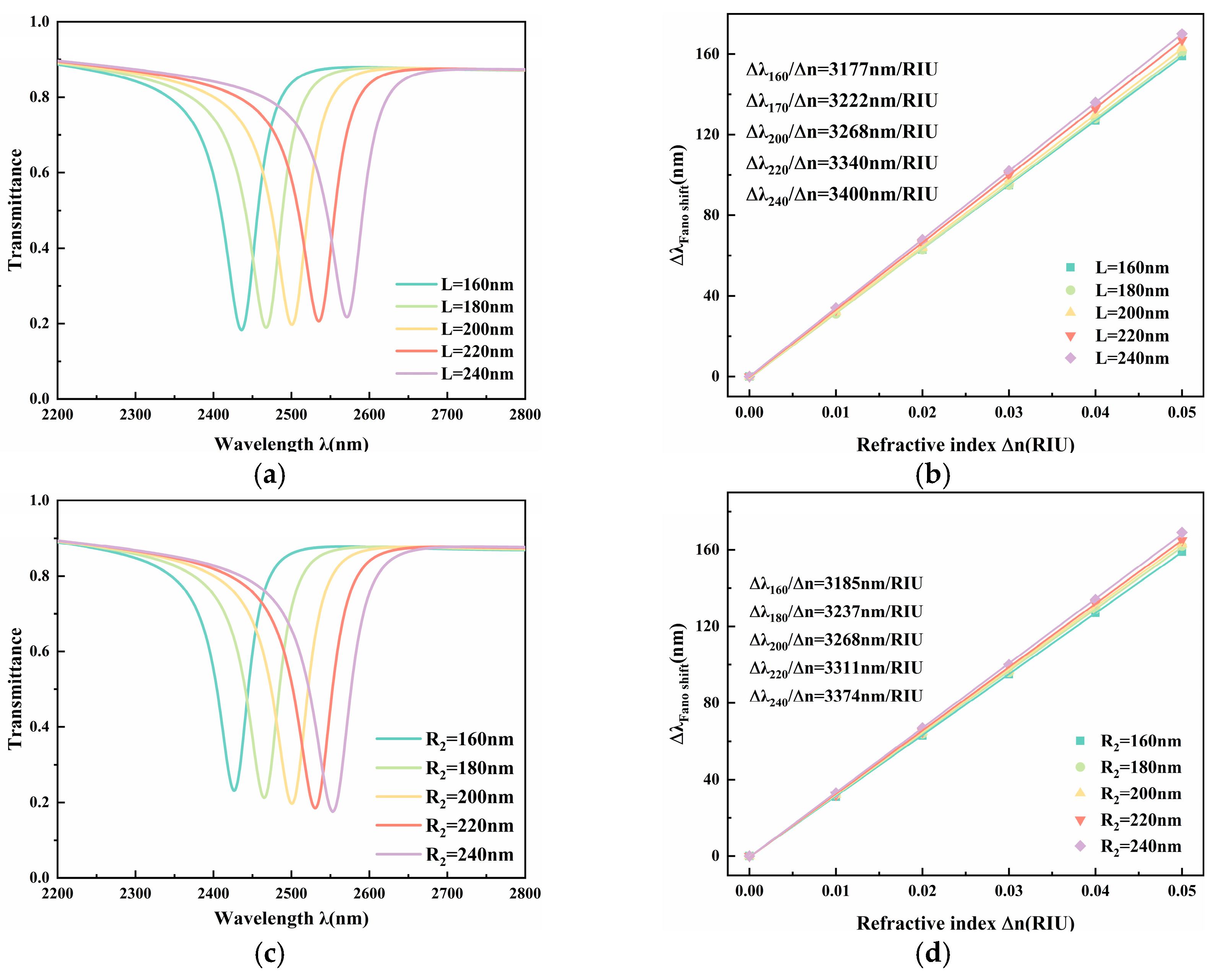

3.2.3. Influence of R2 and L

In order to conduct a thorough evaluation of how geometric dimensions affect sensing capabilities, a systematic investigation was performed on the resonator parameters. Specifically, we swept the side length of the rounded square

R2 and the length of the bridge’s upper rectangular section

L across a range of 160 nm to 240 nm. The corresponding results from these simulations are visualized in

Figure 7.

The analysis shows that

R2 and

L have relatively limited abilities to tune the resonance characteristics and transmission behavior. Specifically, as

L increases, the resonance dip undergoes a redshift and the minimum transmittance increases slightly [

Figure 7a]. An increase in

R2 also induces a redshift in the resonance wavelength, while the minimum transmittance shows a mild reduction [

Figure 7c]. The total shift of the resonance wavelength induced by these two parameters is within 200 nm, and the variation range of transmittance does not exceed 0.1. As can be seen from

Figure 7a–d, when

R2 and

L vary within 160–240 nm, the resonance wavelength and transmittance show some changes, but the variations in sensitivity and FOM are relatively limited. This indicates that the sensor has a high tolerance to

R2 and

L within this size window.

This result also indirectly demonstrates that, as long as rounded square units are introduced on both sides of the ring cavity and a bridge structure is set inside the cavity, the cooperative effect of enhanced field localization and coupling control can be effectively exerted, while being insensitive to specific dimensional fabrication errors.

Considering structural symmetry, fabrication feasibility, and performance stability, R2 = 200 nm and L = 200 nm are finally selected as the typical structural parameters for subsequent analysis and application verification.

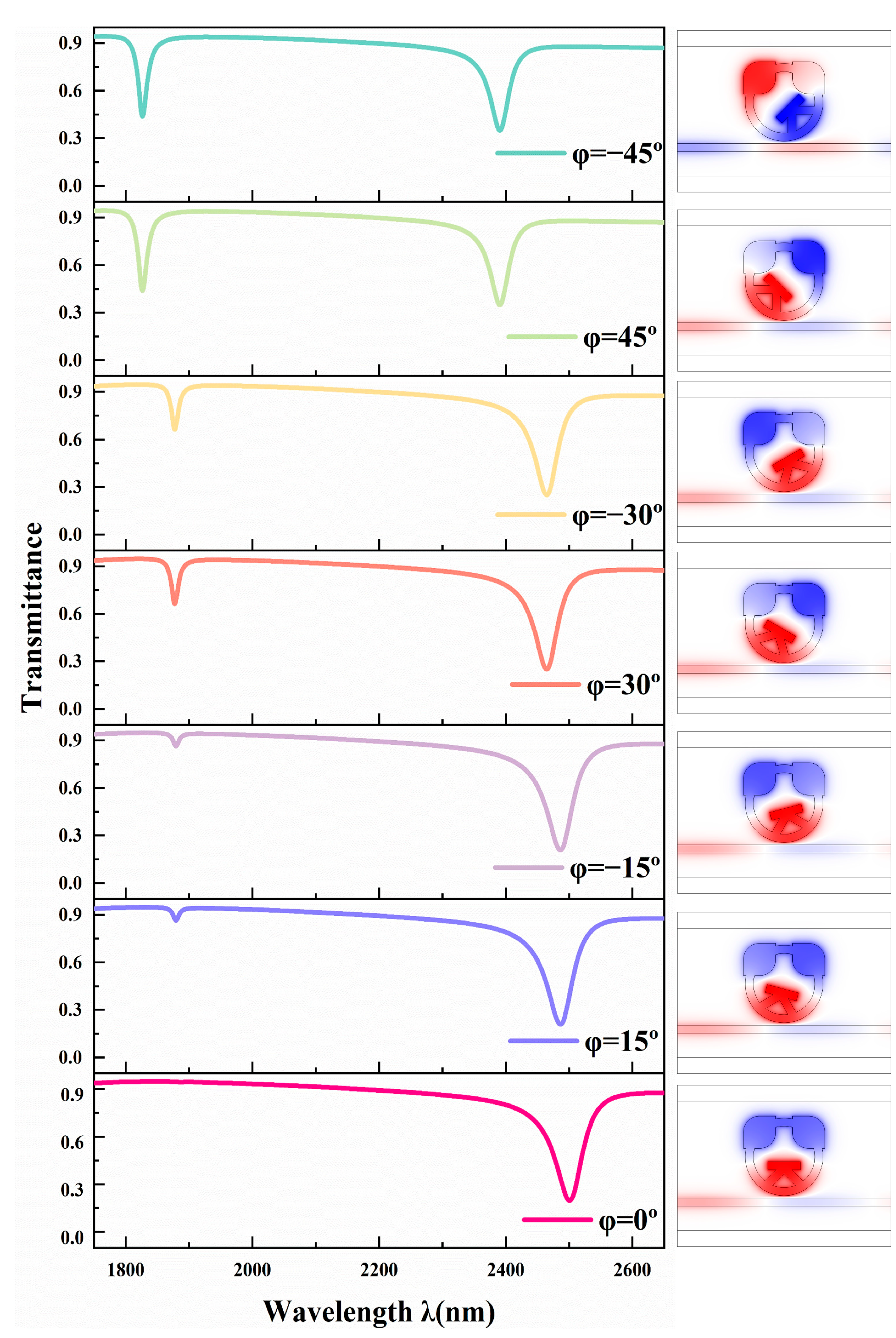

3.2.4. Influence of φ

We systematically studied the transmission spectra and normalized magnetic-field distributions over a

φ range of −45° to 45° to investigate how the bridge rotation angle tunes the sensing characteristics of the RBS resonator, as shown in

Figure 8. It is found that, for opposite rotation directions with the same |φ|, the obtained transmission spectra are nearly identical, indicating that the sensor performance mainly depends on the absolute value of the rotation angle and is insensitive to the specific rotation direction. As |

φ| increases, two main spectral-evolution features can be observed: the original resonance dip in the long-wavelength band gradually increases in transmittance and undergoes a pronounced blueshift; meanwhile, a new resonance dip appears near 1900 nm and its minimum transmittance continuously decreases with increasing |

φ|.

This phenomenon can be explained by the breaking of the original geometric symmetry by the rotation of the bridge structure, which leads to mode splitting. The normalized magnetic-field distributions further show that, with increasing |φ|, the magnetic-field convergence in the cavity weakens, the coupling efficiency decreases, and the resonance modes split and broaden, which is detrimental to sensing performance. Therefore, (φ = 0°) is adopted in this study to maintain optimal performance.

3.3. Assessment of Refractive Index Sensing Performance

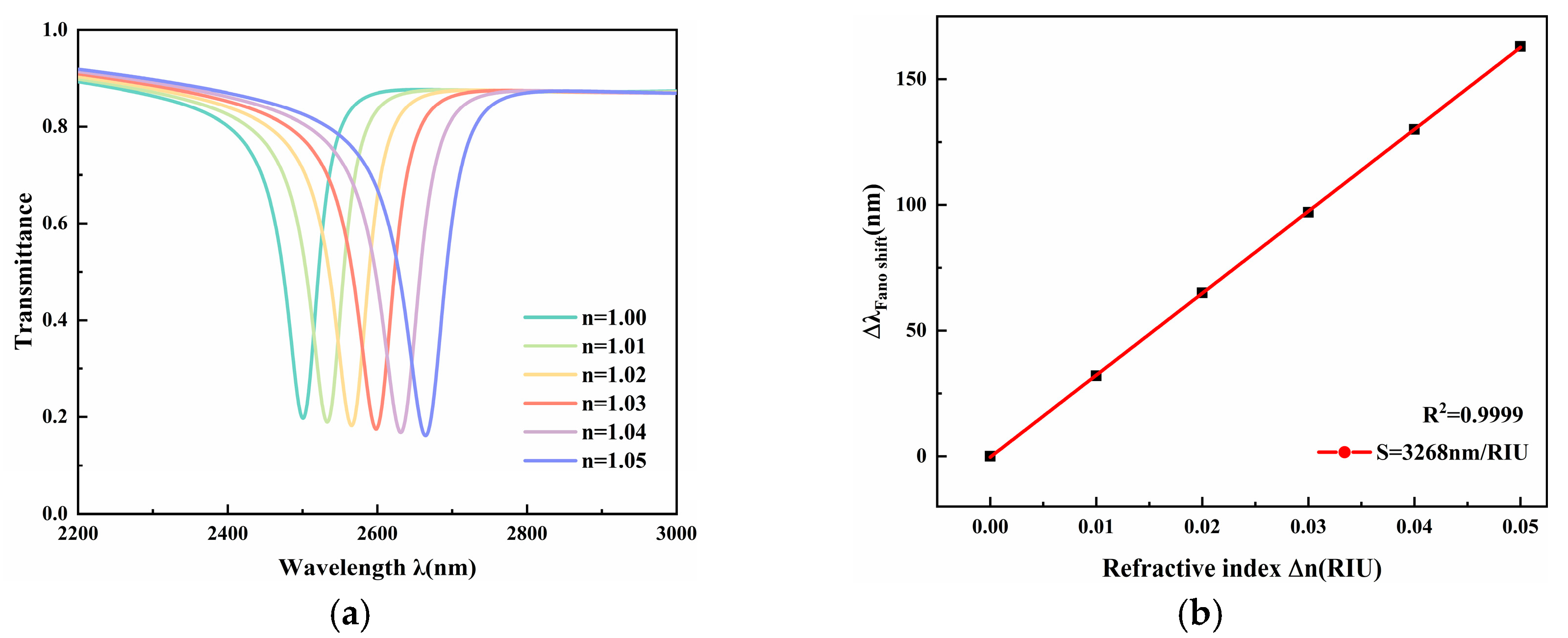

Following a systematic optimization process, the ideal geometric parameters for the resonator were determined. R1, g, φ, R2 and L were identified as 240 nm, 15 nm, 0°, 200 nm, and 200 nm, respectively. Utilizing this optimized configuration, we established a complete sensor architecture comprising a MIM waveguide side-coupled to the RBS resonator to investigate its sensing capabilities.

To evaluate the sensor’s response, the refractive index n of the dielectric medium was incrementally varied from 1.00 to 1.05 in steps of 0.01. As depicted in

Figure 9a, an elevation in n induces a consistent redshift in the Fano resonance dip. Notably, the asymmetric profile of the spectrum remains stable across this index range without significant deformation. The linear relationship between the resonance wavelength and n is plotted in

Figure 9b. This fitting reveals a high sensitivity (S = 3268 nm/RIU). The linearity of the sensing response is quantified by the coefficient of determination (R

2), which is calculated to be 0.9999. This value confirms an excellent linear response. Furthermore, based on the FWHM of 58.9 nm, the FOM is computed to be 55.4. This result highlights the sensor’s ability to deliver high sensitivity alongside robust spectral selectivity.

We objectively evaluated the overall performance of our RBS design by benchmarking it against several recent MIM-waveguide sensors, with a summary provided in

Table 3. This comparative analysis reveals that the proposed sensor achieves leading-edge sensitivity alongside a relatively high FOM. This indicates that the structure successfully achieves a favorable compromise between high sensitivity and high selectivity, and its comprehensive performance surpasses most previously reported similar sensors.

Therefore, the optimized RBS structure can serve as a highly refractive index sensitive platform. By choosing different refractive index sensitive media, it is expected to be extended to various optical sensing applications for external parameters, such as biochemical analysis, concentration detection, and temperature measurement based on the thermo-optic effect.

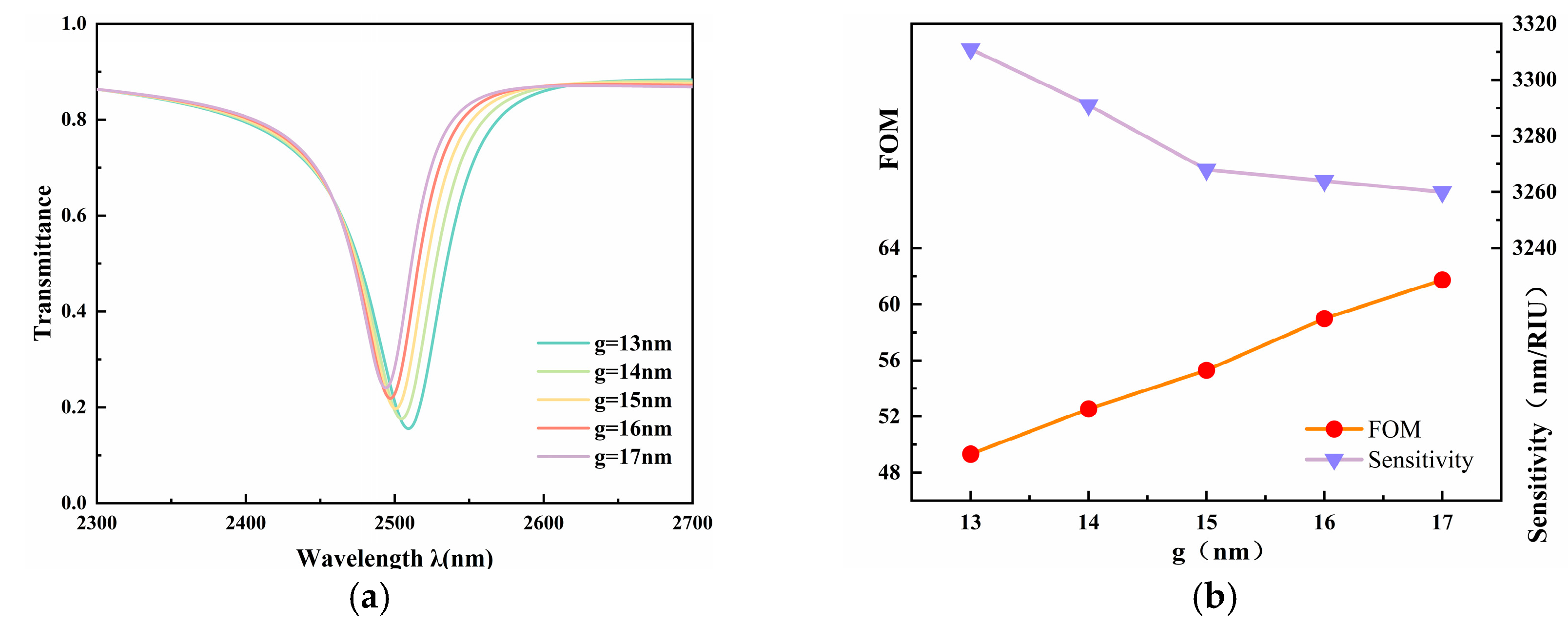

3.4. Manufacturing Feasibility and Tolerance Analysis

Although this work primarily focuses on numerical simulations, evaluating the manufacturability and robustness of the sensor in a practical experimental context is crucial for its real-world application. Based on existing micro-nano fabrication technologies, the proposed RBS structure in this design can be manufactured using established process flows: first, a high-quality silver film is deposited on the substrate via physical vapor deposition or magnetron sputtering, followed by patterning the RBS structure using methods such as electron-beam lithography and etching. Despite the high precision of modern nanofabrication techniques, inevitable minor process deviations in geometric dimensions occur due to limitations like the electron-beam proximity effect or lateral etching during the process.

Our earlier parameter optimization revealed that the most distinctive parameters of this structure—the rounded square parameter R2 and the parameter L of the bridge structure embedded within the ring cavity—are not highly sensitive to sensor performance. Specifically, large-scale variations in these parameters result in minimal changes to the FOM and S, indicating the structure’s tolerance for significant manufacturing errors. Conversely, the coupling distance g between the waveguide and the resonator is the most sensitive parameter, critically affecting the coupling strength and the lineshape of the Fano resonance. Therefore, g is the key parameter most susceptible to manufacturing errors and subsequent impact on sensor performance.

To verify the design’s robustness, we simulated the performance evolution based on the determined optimal parameters while varying g within a range of 13 nm to 17 nm (corresponding to a typical manufacturing tolerance of 15 ± 2 nm).

Figure 10b shows the trajectories of S and FOM as

g varies. The results indicate that as

g increases from 13 nm to 17 nm, the FOM shows a rising trend due to subtle changes in coupling efficiency, while the sensitivity, despite slight fluctuations, consistently remains at a high level above 3240 nm/RIU. It is noteworthy that even with a dimensional deviation of ±2 nm, the sensor can still maintain excellent sensing performance. This demonstrates that the optimal design point lies within an insensitive region of the parameter space rather than at a critical point extremely sensitive to errors. Consequently, minor errors arising from manufacturing processes will not have a significant impact on the sensor’s performance. This high error-tolerance characteristic confirms that the RBS structure can accommodate existing nanofabrication precision, providing reliable theoretical assurance for future experimental fabrication.

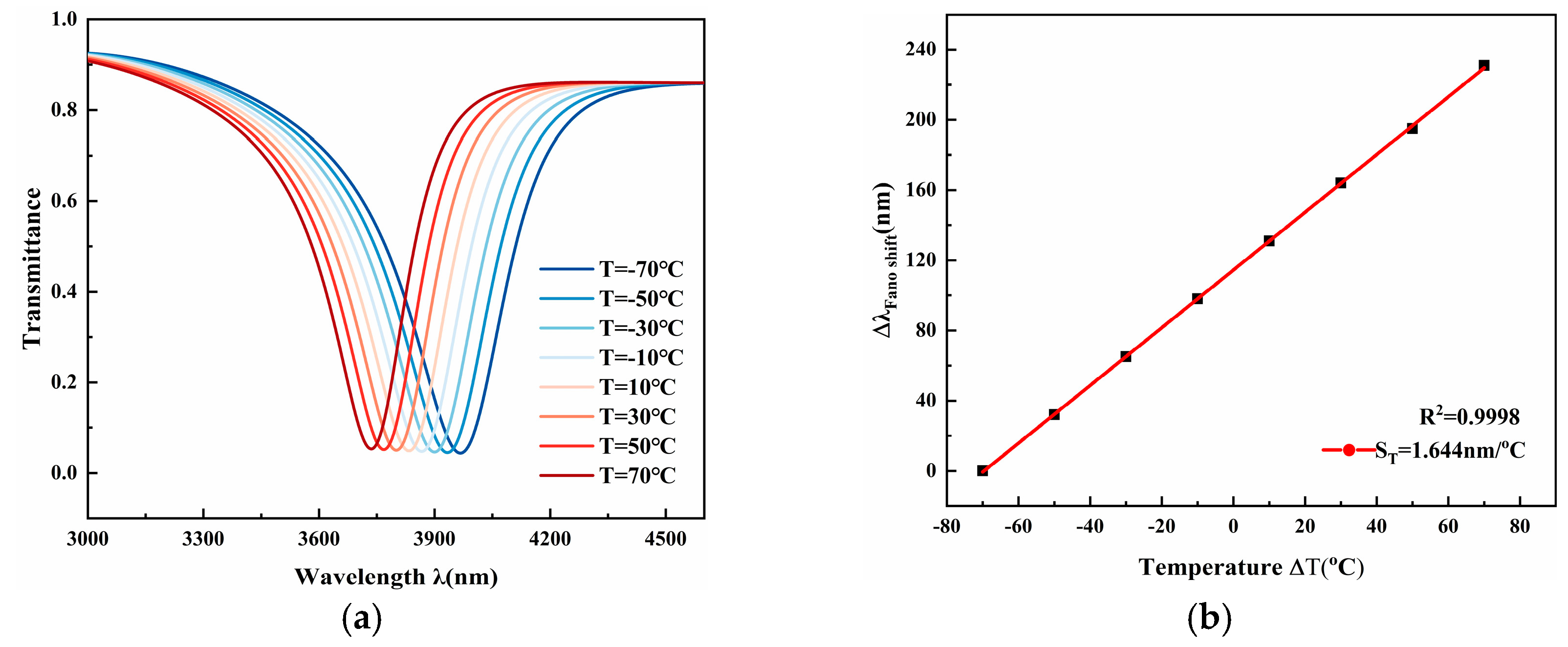

4. Temperature Sensing Application

Based on the superior refractive-index sensing metrics of the proposed RBS structure (Sensitivity = 3268 nm/RIU; FOM = 55.4), we extended the investigation to construct a high-performance optical temperature sensor. The sensing principle is grounded in the thermo-optic effect, where temperature fluctuations T modulate the refractive index n of the medium. These index variations within the cavity and waveguide modify the SPP resonance conditions, inducing a shift Δλ in the Fano resonance dip. By establishing the correlations among T, n, and λ, the temperature change ΔT can be deduced from the spectral shift.

Ethanol was selected as the functional liquid due to its significant thermo-optic coefficient in the target band [

37], ensuring that temperature variations trigger substantial index changes and subsequent wavelength shifts. The refractive index of ethanol varies with ambient temperature according to the empirical equation [

38]:

For the thermal performance evaluation, the geometric parameters were maintained at the optimized configuration derived from the RI sensing analysis. Specifically, the radii were set to R1 = 240 nm and R2 = 200 nm, while the waveguide width w and the gap distance g were fixed at 50 nm and 15 nm, respectively. The cavity length L was kept at 200 nm with a phase angle φ of 0°. In the simulations, ethanol served as the filling medium. Data were collected over the range of −70 °C to 70 °C with a sampling interval of 20 °C, yielding eight distinct data points for analysis. Ethanol has a melting point of −114.1 °C and a boiling point of 78.37 °C, ensuring a stable liquid phase within the operational range of −70 °C to 70 °C. To mitigate the impact of extreme operating conditions, a microfluidic cavity is recommended for practical implementation.

Figure 11a displays the transmission spectra evolution. A continuous blueshift is evident as the temperature rises, while the Fano line shape remains stable. Notably, as the temperature increases from −70 °C to 70 °C, the resonance wavelength moves from ~3967 nm to ~3736 nm. This results in a substantial total shift (Δ

λ) of 231 nm across the 140 °C span, facilitating signal demodulation.

The linearity of the device is depicted in

Figure 11b, where the resonance wavelengths are plotted against temperature. The high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.9998) confirms an excellent linear response. The temperature sensitivity

ST, which represents the slope of the fitting line, is a critical performance indicator defined as [

39]:

The calculated sensitivity is 1.644 nm/°C. This high sensitivity, paired with superior linearity, enables the reliable detection of minute temperature variations, making the proposed sensor a promising candidate for high-precision optical monitoring.

Furthermore, it is worth highlighting that the proposed sensor is not limited to temperature sensing; it holds significant potential for various biochemical applications, such as glucose detection and hemoglobin analysis. However, in practical sensing environments, the simultaneous fluctuation of ambient temperature and the analyte’s refractive index may induce signal crosstalk. To address this issue without compromising the high sensitivity and compact footprint of the optimized RBS sensor, system-level compensation strategies are recommended for future implementation. For instance, a dual-channel reference mechanism can be adopted by integrating two parallel RBS resonators on the sensing chip, where one serves as a reference unit sensitive only to temperature (isolated from the analyte). By subtracting the spectral shift of the reference channel from the sensing channel, noise induced by environmental factors can be effectively decoupled. Alternatively, data-driven temperature compensation algorithms can be applied during the signal demodulation process to further ensure measurement accuracy.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper proposes and numerically investigates a novel plasmonic sensor designed with an MIM waveguide coupled to an RBS resonator. By incorporating rounded-square elements and a bridge-like architecture into a conventional ring resonator, the structure significantly improves modal interference and optical field confinement. Numerical investigations utilizing FEM demonstrate that the device generates a distinct, sharp asymmetric Fano resonance profile. It was observed that varying the geometric parameters exerts a strong impact on both the resonance wavelength and linewidth, thereby enabling precise tunability of the sensing characteristics. Under optimized structural conditions, the sensor attains a peak refractive index sensitivity of 3268 nm/RIU alongside a FOM of 55.4, metrics that surpass those of numerous recently published designs. Furthermore, by leveraging the thermo-optic properties of ethanol, the system functions effectively for temperature sensing, exhibiting a linear sensitivity of 1.644 nm/°C with a high linearity coefficient (R2 = 0.9998). Given its compact footprint, facile integration, and superior performance, the proposed RBS sensor offers significant promise for applications in high-precision detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and S.Y.; methodology, W.L.; software, S.Y.; validation, W.L., Z.X. and Y.C.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, B.H., G.L. and D.Z.; resources, S.Y.; data curation, T.W. and Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.; visualization, B.H.; supervision, D.Z.; project administration, S.Y.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62374148 and in part by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LD21F050001, the Key Research Project by the Department of Water Resources of Zhejiang Province under Grant No. RA2101, the Key Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province under Grant No. 2021C03019, and the Funds for Special Projects of the Central Government in Guidance of Local Science and Technology Development under Grant No. YDZJSX20231A031.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to other colleagues in their laboratory for their understanding and help. They also appreciate the affiliated institution to provide research platform and the sponsor to provide financial support for them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haddouche, I.; Cherbi, L. Comparison of Finite Element and Transfer Matrix Methods for Numerical Investigation of Surface Plasmon Waveguides. Opt. Commun. 2017, 382, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, W.L.; Dereux, A.; Ebbesen, T.W. Surface Plasmon Subwavelength Optics. Nature 2003, 424, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Liu, X.; Mao, D.; Wang, G. Plasmonic Nanosensor Based on Fano Resonance in Waveguide-Coupled Resonators. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhevolnyi, S.I.; Volkov, V.S.; Devaux, E.; Laluet, J.-Y.; Ebbesen, T.W. Channel Plasmon Subwavelength Waveguide Components Including Interferometers and Ring Resonators. Nature 2006, 440, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, Y.; Rosa, L.; Juodkazis, S. Surface Plasmon Resonances in Periodic and Random Patterns of Gold Nano-Disks for Broadband Light Harvesting. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramotnev, D.K.; Bozhevolnyi, S.I. Plasmonics beyond the Diffraction Limit. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk’yanchuk, B.; Zheludev, N.I.; Maier, S.A.; Halas, N.J.; Nordlander, P.; Giessen, H.; Chong, C.T. The Fano Resonance in Plasmonic Nanostructures and Metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Liu, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yi, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Hao, Z. Four Peak and High Angle Tilted Insensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance Graphene Absorber Based on Circular Etching Square Window. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 185305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yi, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, C.; Deng, J.; Li, B. Structural Design and Analysis of D-Type Elliptical Open-Loop Photonic Crystal Fiber Temperature Sensor Based on SPR. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 715, 417549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Yu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, P. A Switchable Terahertz Device Combining Ultra-Wideband Absorption and Ultra-Wideband Complete Reflection. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 2527–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liang, R.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Xu, X. Plasmonic Filters and Optical Directional Couplers Based on Wide Metal-Insulator-Metal Structure. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Shi, F.; Chen, Y. Unidirectional All-Optical Absorption Switch Based on Optical Tamm State in Nonlinear Plasmonic Waveguide. Plasmonics 2016, 11, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Wang, Q.J.; Huang, X.G. All-Optical Plasmonic Switches Based on Coupled Nano-Disk Cavity Structures Containing Nonlinear Material. Plasmonics 2011, 6, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Tai, R. Plasmonic Luneburg Lens and Plasmonic Nano-Coupler. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2020, 18, 092401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yan, S. Fano Resonance in an Asymmetric MIM Waveguide Structure and Its Application in a Refractive Index Nanosensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, L.; Duan, G.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, J. Sharp Asymmetric Line Shapes in a Plasmonic Waveguide System and Its Application in Nanosensor. J. Light. Technol. 2015, 33, 3250–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jin, G. Detecting the Temperature of Ethanol Based on Fano Resonance Spectra Obtained Using a Metal-Insulator-Metal Waveguide with SiO2 Branches. Opt. Mater. Express 2021, 11, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Yousuf, M.A.; Islam, N. Multiple Fano Resonance Modes Based Plasmonic Refractive Index Sensor for Edible Oil Adulteration Detection. Optik 2024, 312, 171961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, J.D.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahad, R.; Chowdhury, A.; Chowdhury, M.H. A Novel and Effective Oxidation-Resistant Approach in Plasmonic MIM Biosensors for Real-Time Detection of Urea and Glucose in Urine for Monitoring Diabetic and Kidney Disease Severity. Opt. Commun. 2024, 573, 131012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Shu, C.; Ye, H. The Sensing Characteristics of Plasmonic Waveguide with a Ring Resonator. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yan, S.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Chang, S.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Wu, T.; Ren, Y. Nanoscale Refractive Index Sensor Based on an MIM Waveguide Coupled to U-Shaped Ring Resonator with Three Stubs for Alcohol Solution Concentration Detection. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 2421–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Qin, F.; Yi, Z.; Yao, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wu, P. Ultra-Wideband and Wide-Angle Perfect Solar Energy Absorber Based on Ti Nanorings Surface Plasmon Resonance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 17041–17048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.F.; Sagor, R.H.; Amin, M.R.; Islam, M.R.; Alam, M.S. Point of Care Detection of Blood Electrolytes and Glucose Utilizing Nano-Dot Enhanced Plasmonic Biosensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17749–17757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, J.A.; Sweatlock, L.A.; Atwater, H.A.; Polman, A. Plasmon Slot Waveguides: Towards Chip-Scale Propagation with Subwavelength-Scale Localization. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 035407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, H.; Wang, J.; Tian, Q. Modified Debye Model Parameters of Metals Applicable for Broadband Calculations. Appl. Opt. 2007, 46, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.U.; D’Archangel, J.; Sundheimer, M.L.; Tucker, E.; Boreman, G.D.; Raschke, M.B. Optical Dielectric Function of Silver. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 235137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekatpure, R.D.; Hryciw, A.C.; Barnard, E.S.; Brongersma, M.L. Solving Dielectric and Plasmonic Waveguide Dispersion Relations on a Pocket Calculator. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 24112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Yan, S.; Xu, Z.; Chen, C.; Cao, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, T. Multi-Structure-Based Refractive Index Sensor and Its Application in Temperature Sensing. Sensors 2025, 25, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.M.; Hafner, J.H. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3828–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevich, N.; Gertner, I. Comparison among Methods for Calculating FWHM. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 1989, 283, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, F.; Ebrahimi, S. Planar Optical Waveguide for Refractive Index Determining with High Sensitivity and Dual-Band Characteristic for Nano-Sensor Application. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2019, 51, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, J. Glycerol Concentration Sensor Based on the MIM Waveguide Structure. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 1026494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qu, D.; Wu, Q.; Li, C. Multiple Independently Controllable Fano Resonances Based on the MIM Waveguide and Their Application in Sensing. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuigue, M.; Mahboub, O.; El Haffar, R. Optical Properties of Multiple Fano Resonance in MIM Waveguide System Coupled with a Semi-Elliptical Ring Resonator. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Liu, F.; Chang, S.; Cao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y. Refractive Index Sensor Based on an Annular Cavity and an Equilateral Triangular Cavity for Temperature Detection. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 85120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Cao, H. Fano Resonant Sensing in MIM Waveguide Structures Based on Multiple Circular Split-Ring Resonant Cavities. Micromachines 2025, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ye, H.; Peng, Y.; Shu, C.; Yang, C.; Zhang, W.; He, H. A Nanometeric Temperature Sensor Based on Plasmonic Waveguide with an Ethanol-Sealed Rectangular Cavity. Opt. Commun. 2015, 339, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.-Y.; Liang, R.-S.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Yi, L.-X.; Lai, G.; Zhao, R.-T. Multifunctional Disk Device for Optical Switch and Temperature Sensor. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, S.; Cui, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, G. A Nanosensor Based on Optical Principles for Temperature Detection Using a Gear Ring Model. Photonics 2024, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional schematic diagram of the sensor structure.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional schematic diagram of the sensor structure.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the numerical-simulation flow.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the numerical-simulation flow.

Figure 3.

Transmission spectra of different structures: only straight waveguide (blue), waveguide + ring resonator (green), waveguide + ring resonator with bridge (yellow), waveguide + ring resonator with rounded square units (red), and complete RBS structure (purple).

Figure 3.

Transmission spectra of different structures: only straight waveguide (blue), waveguide + ring resonator (green), waveguide + ring resonator with bridge (yellow), waveguide + ring resonator with rounded square units (red), and complete RBS structure (purple).

Figure 4.

Normalized magnetic-field distributions of different structures at their respective resonance wavelengths: (a) Waveguide + Ring Resonator; (b) Waveguide + Ring Resonator with Rounded Square units on both sides; (c) Waveguide + Ring Resonator with internal bridge structure; (d) Complete Structure.

Figure 4.

Normalized magnetic-field distributions of different structures at their respective resonance wavelengths: (a) Waveguide + Ring Resonator; (b) Waveguide + Ring Resonator with Rounded Square units on both sides; (c) Waveguide + Ring Resonator with internal bridge structure; (d) Complete Structure.

Figure 5.

(a) Transmission spectra for different R1; (b) Linear-fit lines of sensitivity corresponding to different R1.

Figure 5.

(a) Transmission spectra for different R1; (b) Linear-fit lines of sensitivity corresponding to different R1.

Figure 6.

(a) Transmission spectra for different g; (b) Linear-fit lines of resonance wavelength versus refractive index for different g; (c) FWHM for different g; (d) FOM for different g.

Figure 6.

(a) Transmission spectra for different g; (b) Linear-fit lines of resonance wavelength versus refractive index for different g; (c) FWHM for different g; (d) FOM for different g.

Figure 7.

Parameter sweep analysis for resonator dimensions: (a) Transmission spectra and (b) corresponding sensitivity fits under varying bridge lengths L; (c) Transmission spectra and (d) sensitivity fits for different rounded square side lengths R2.

Figure 7.

Parameter sweep analysis for resonator dimensions: (a) Transmission spectra and (b) corresponding sensitivity fits under varying bridge lengths L; (c) Transmission spectra and (d) sensitivity fits for different rounded square side lengths R2.

Figure 8.

Spectral evolution and magnetic field pattern changes induced by rotating the bridge structure at different angles φ ranging from −45° to 45°.

Figure 8.

Spectral evolution and magnetic field pattern changes induced by rotating the bridge structure at different angles φ ranging from −45° to 45°.

Figure 9.

Refractive index sensing performance: (a) Evolution of the transmission profiles with varying ambient refractive indices; (b) Linear regression analysis correlating the resonance wavelength shift to the refractive index variations.

Figure 9.

Refractive index sensing performance: (a) Evolution of the transmission profiles with varying ambient refractive indices; (b) Linear regression analysis correlating the resonance wavelength shift to the refractive index variations.

Figure 10.

Tolerance Analysis: (a) Transmission spectra for different g (15 ± 2 nm); (b) FOM and S for different g (15 ± 2 nm).

Figure 10.

Tolerance Analysis: (a) Transmission spectra for different g (15 ± 2 nm); (b) FOM and S for different g (15 ± 2 nm).

Figure 11.

(a) Transmission spectra at different temperatures; (b) Linear fit of resonance wavelength versus temperature.

Figure 11.

(a) Transmission spectra at different temperatures; (b) Linear fit of resonance wavelength versus temperature.

Table 1.

Key geometric parameters of the RBS resonator structure.

Table 1.

Key geometric parameters of the RBS resonator structure.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|

| R1 | Outer radius of the ring resonator |

| r1 | Inner radius of the ring resonator |

| G | Gap between waveguide and resonator (coupling distance) |

| W | Width of the MIM waveguide, ring wall, and internal bridge structure |

| R2 | Side length of the rounded-square units |

| L | Length of the upper rectangular part of the bridge structure |

| φ | Rotation angle of the bridge structure |

Table 2.

The model parameters for silver.

Table 2.

The model parameters for silver.

| Symbol | Value | Parameter and Description |

|---|

| 3.8344 | High-frequency permittivity limit of silver |

| −9530.5 | Static permittivity of silver |

| 7.35 × 10−15 s | Electron collision relaxation time in silver |

| 1.1486 × 107 S/m | Electrical conductivity of silver [27] |

| 8.854187817 × 10−12 F/m | Vacuum permittivity (fundamental constant) |

Table 3.

Performance comparison between the proposed sensor and similar structures.

Table 3.

Performance comparison between the proposed sensor and similar structures.

| Reference | Year | Structure | Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | FOM |

|---|

| [32] | 2022 | Circular split ring

resonator | 1200 | 53 |

| [33] | 2023 | Analogous M-shaped and semi-ellipse | 1980 | 24.44 |

| [34] | 2024 | A Baffle Coupled to a Semi-Elliptical Ring Resonator | 1783 | 27 |

| [35] | 2024 | Equilateral Triangular Ring Cavity Structure | 2880 | 50.53 |

| [36] | 2025 | Multiple Circular Split-Ring Resonator Cavities | 946.88 | 99.17 |

| This work | 2025 | Ring-Bridge-Rounded Square (RBS) Resonator | 3268 | 55.4 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |