Experimental Research of Inter-Satellite Beaconless Laser Communication Tracking System Based on Direct Fiber Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

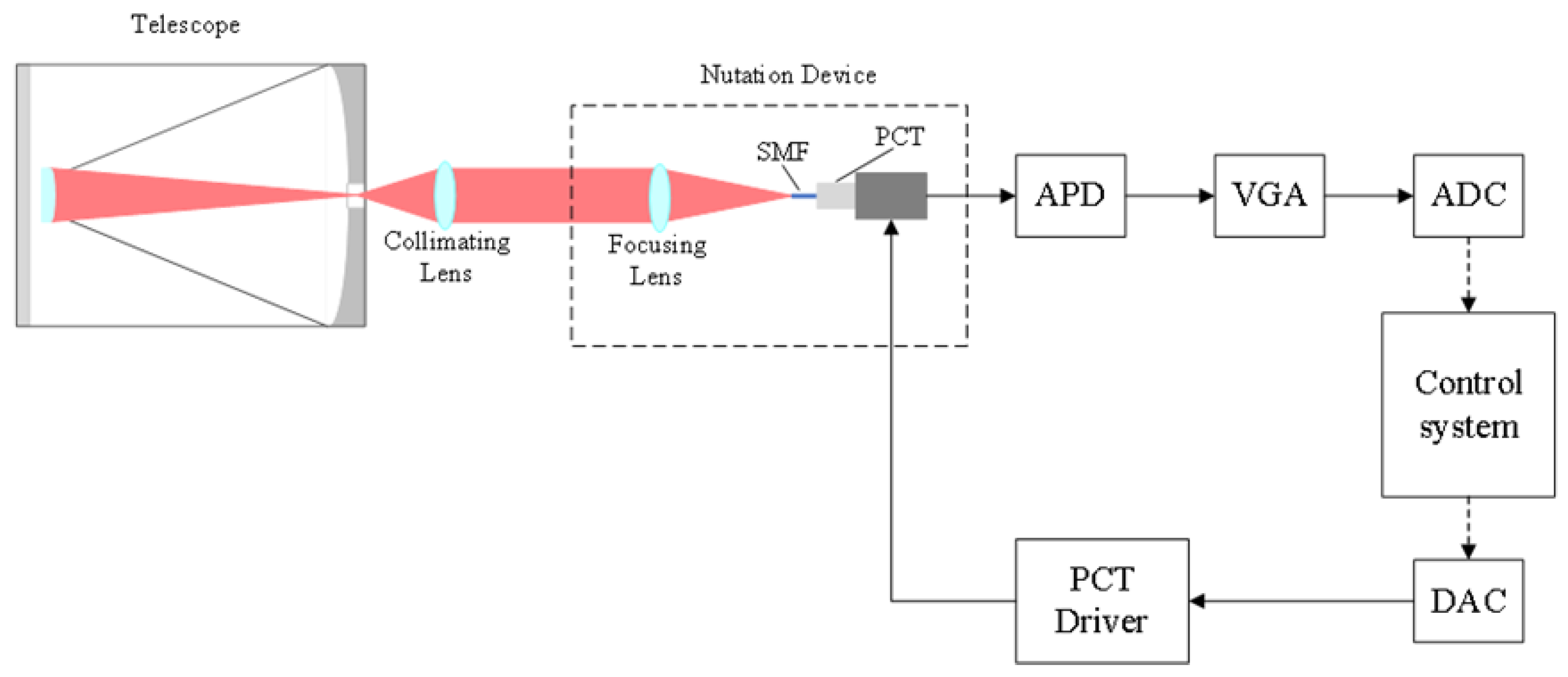

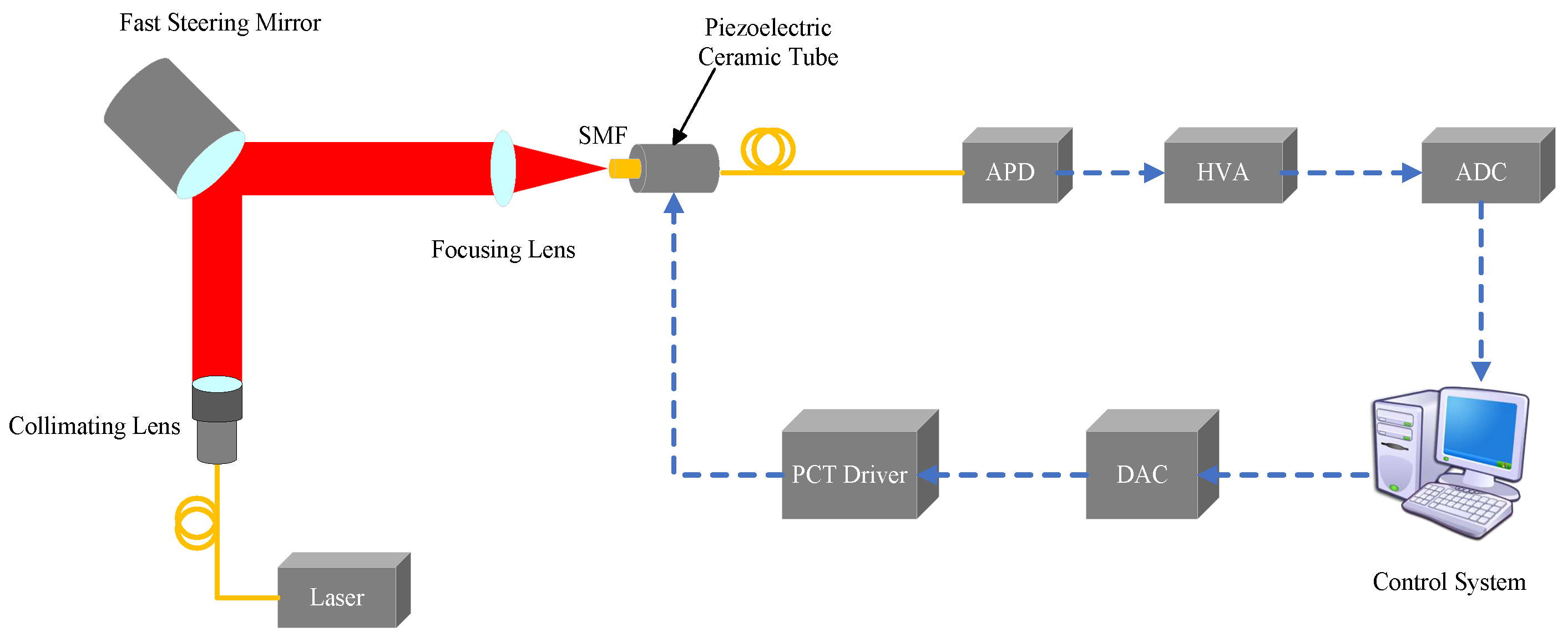

2. System Architecture

3. Fiber Nutation Principle Based on Direct Fiber Control

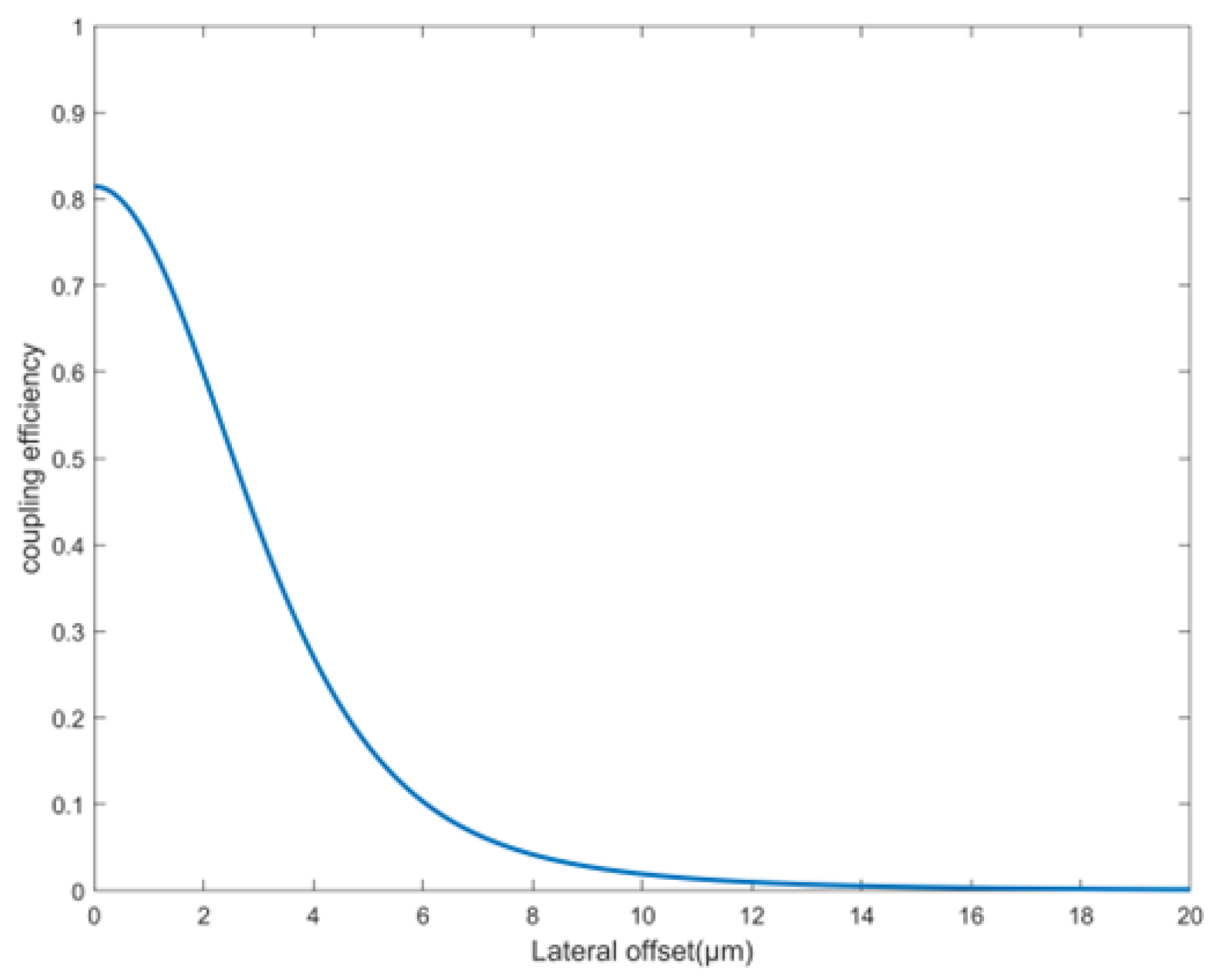

3.1. Principle of SMF Coupling

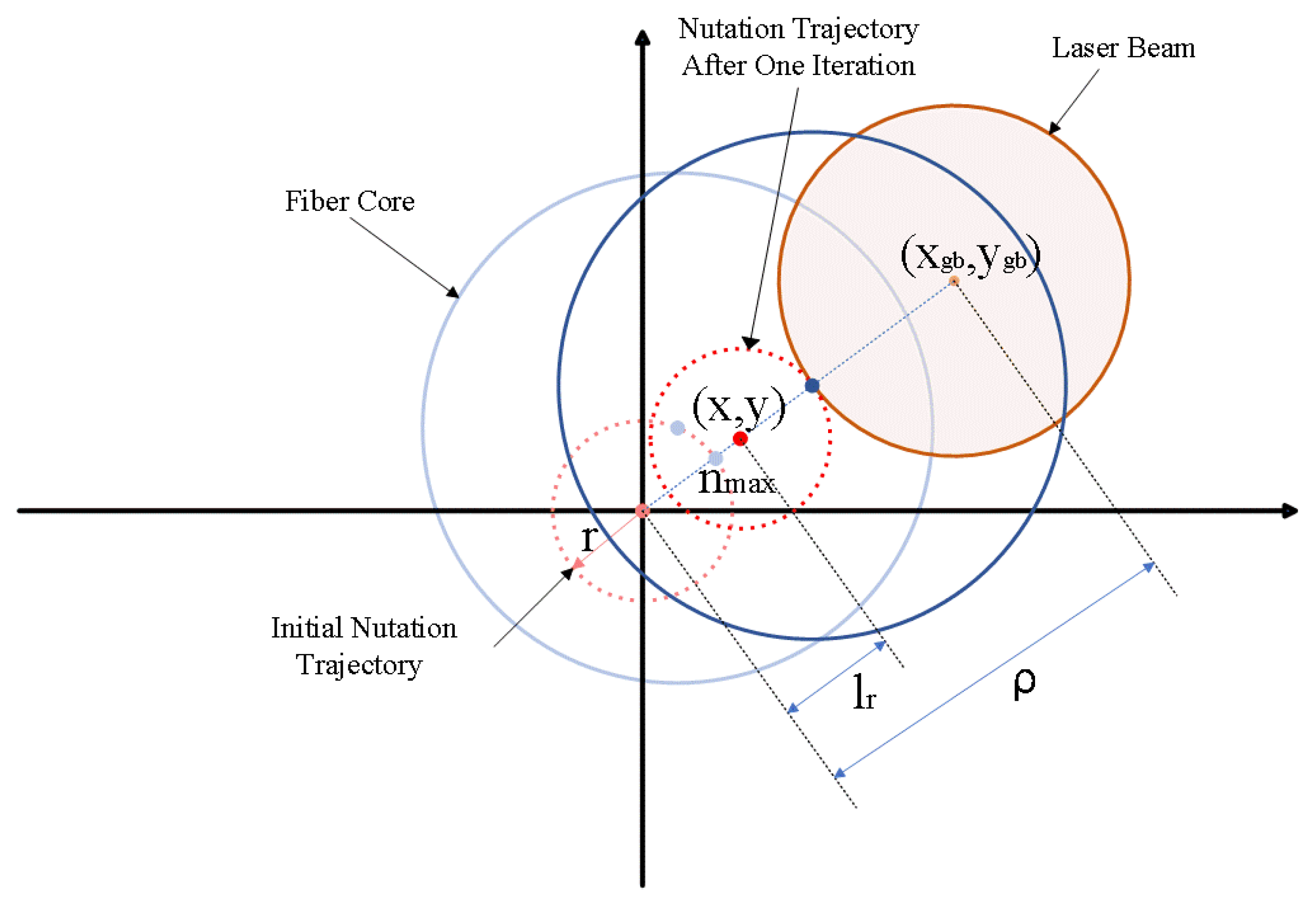

3.2. Algorithm for Fiber Coupling

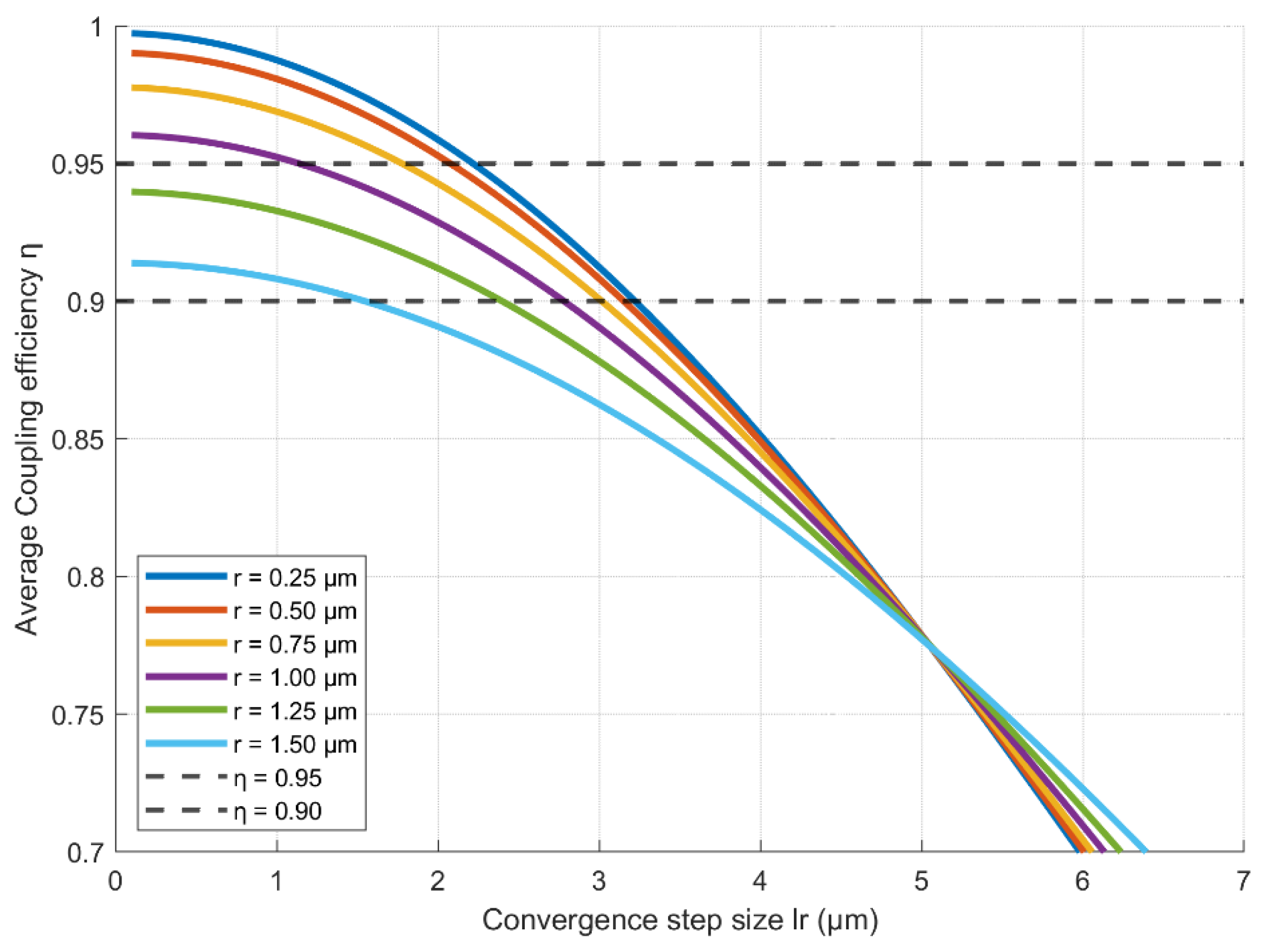

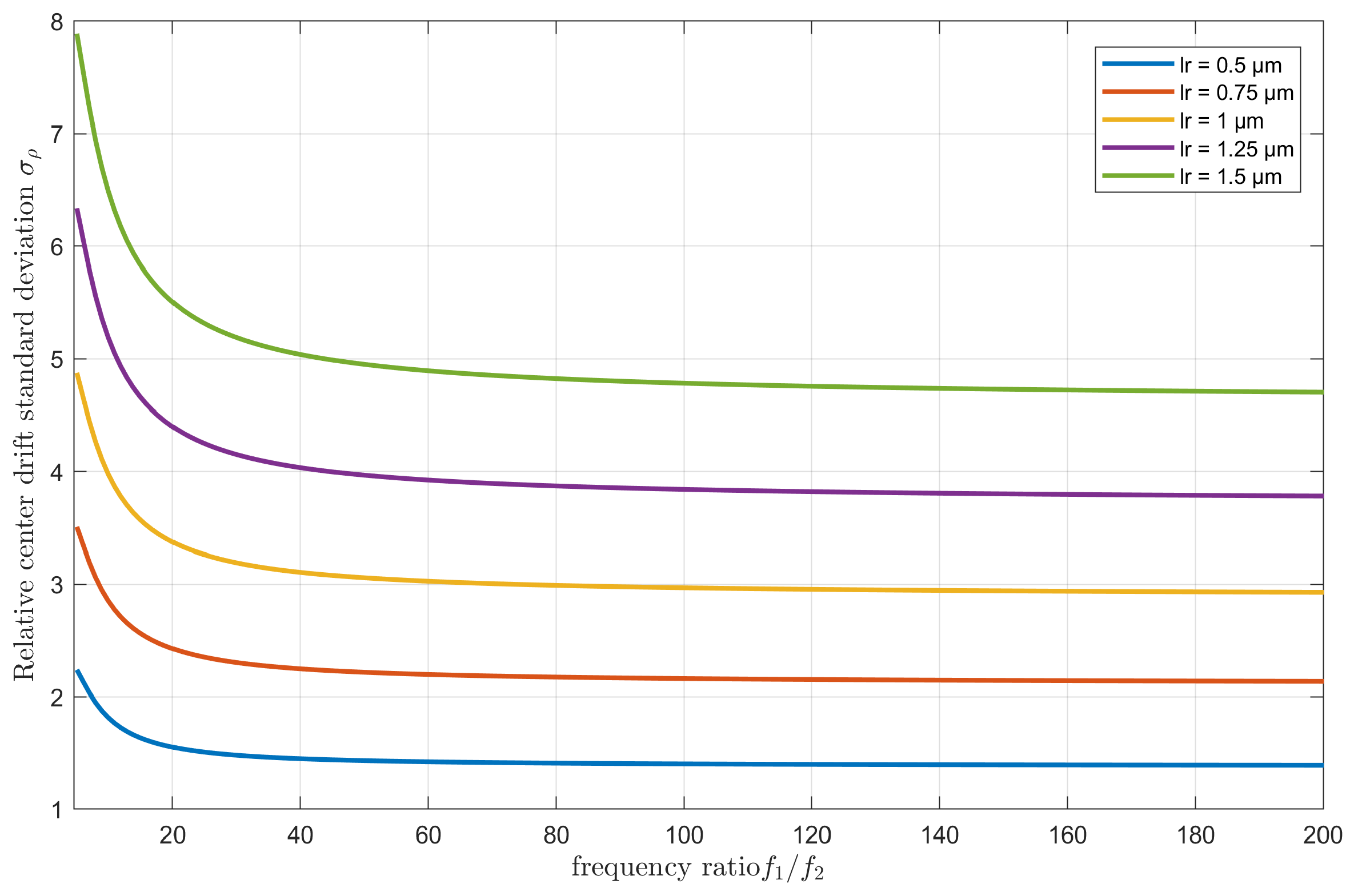

3.3. Tracking Performance Evaluation

4. Experiment

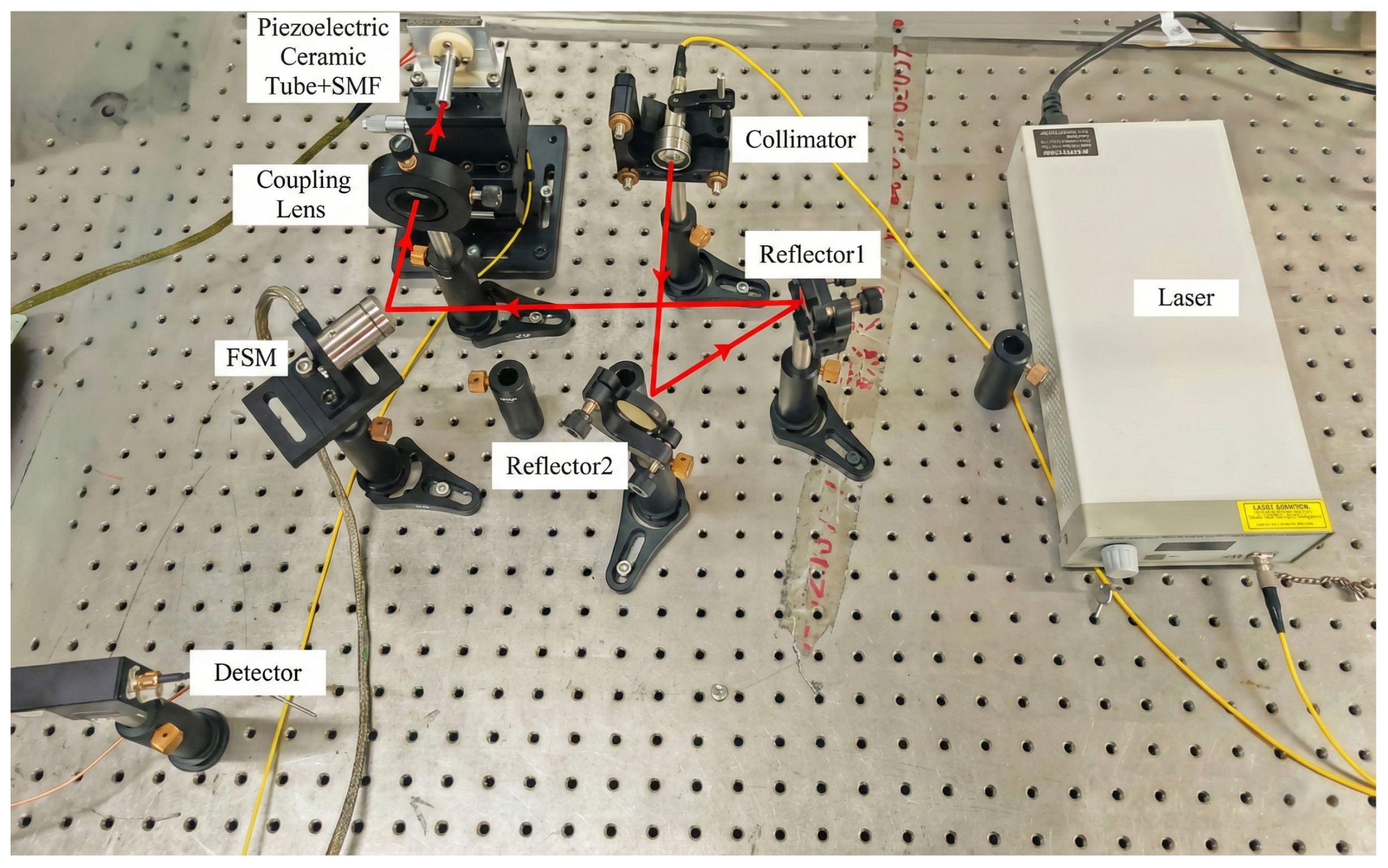

4.1. Set Up

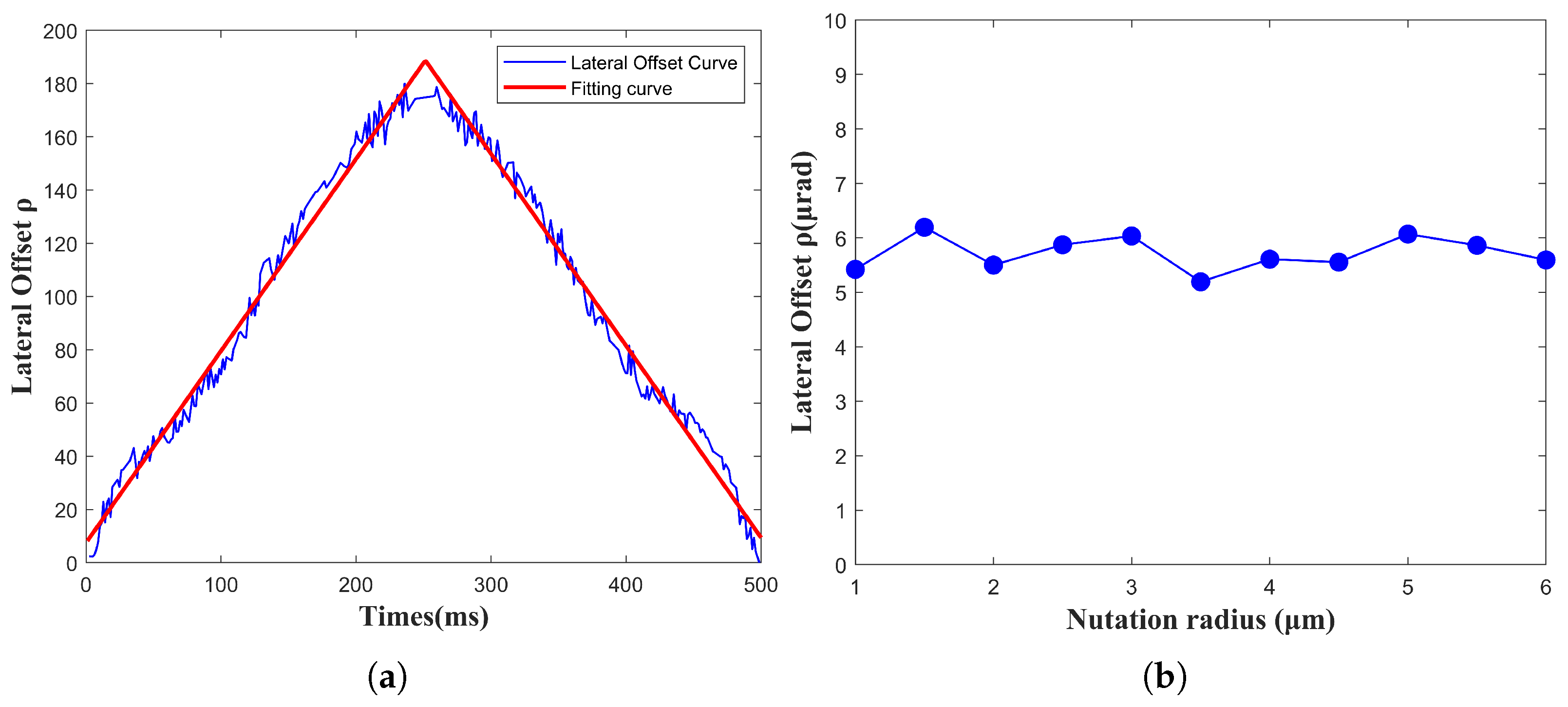

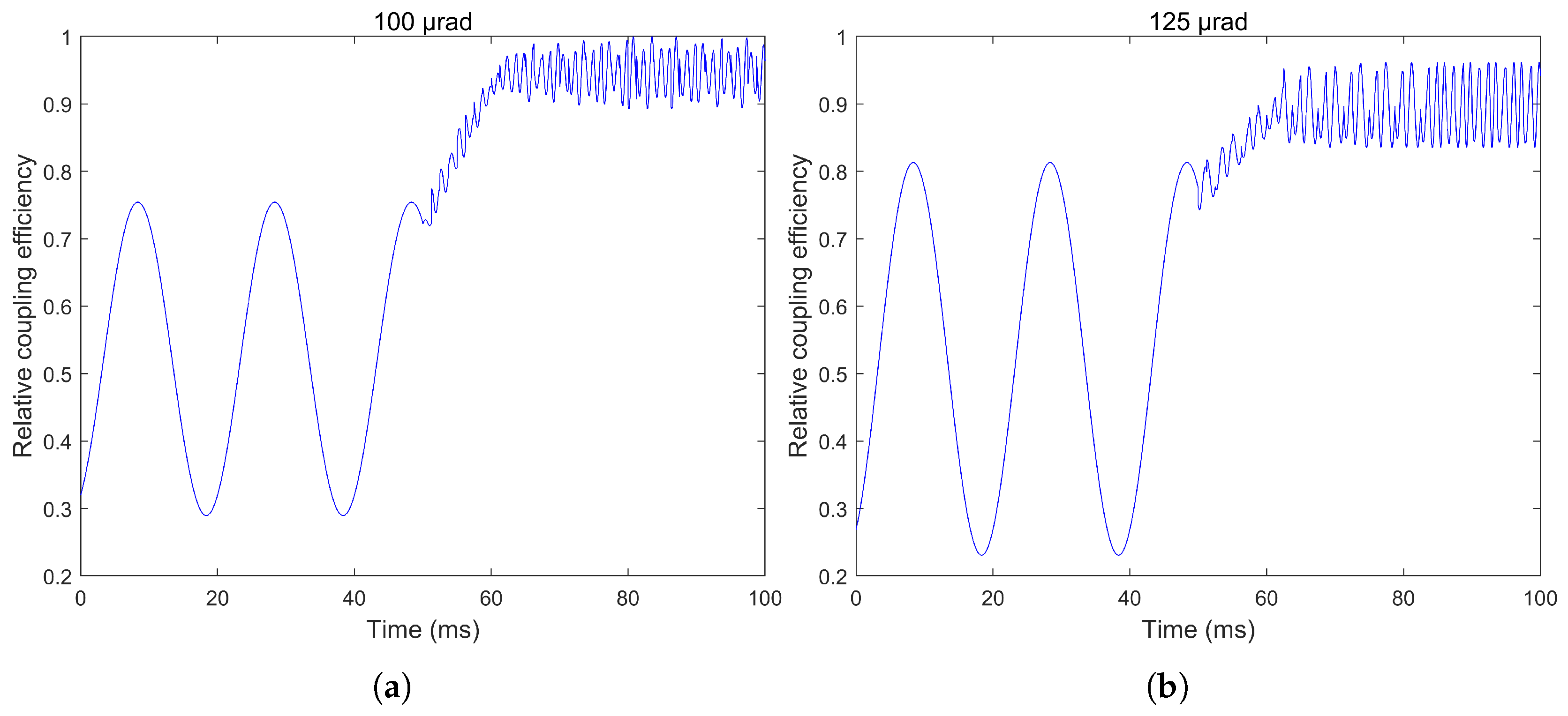

4.2. The Performance of the Closed-Loop System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, S.L.; Yun, H.; Tang, S. Development of multi-target acquisition, pointing and tracking system for airborne laser communication. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2019, 15, 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.S.; Wang, F.; Wu, W. Current status and key technologies of unmanned aerial vehicle laser communication payloads. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2016, 53, 080005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Mai, V.; Kim, H. Acquisition time in laser inter-satellite link under satellite vibrations. IEEE Photon. J. 2023, 15, 7303009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.; Kim, H. Standard deviation of fiber-coupling efficiency for free-space optical communication through atmospheric turbulence. IEEE Photonics J. 2023, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.S.; Zhang, J.Q.; Dang, J.J.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, G.; Fu, P.; Qu, J.; Hoenders, B.J.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y. Enhanced fiber-coupling efficiency via high-order partially coherent flat-topped beams for free-space optical communications. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 5634–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.T.; Zhen, L.L.; Yao, M.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, G. Adaptive stochastic parallel gradient descent approach for efficient fiber coupling. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 13141–13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.J.; Qi, B.; Li, H.; Mao, Y. AS-SPGD algorithm to improve convergence performance for fiber coupling in free space optical communication. Opt. Commun. 2022, 519, 128397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguri, S.; Raj, A.; Sharma, N. Survey on acquisition, tracking and pointing (ATP) systems and beam profile correction techniques in FSO communication systems. J. Opt. Commun. 2024, 45, 881–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaševičius, M.; Mačiulis, L. A review of mechanical fine-pointing actuators for free-space optical communication. Aerospace 2024, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, J.; Wang, C.; Xie, M.; Liu, P.; Cao, Y.; Jing, F.; Wang, F.; Su, Y.; Meng, X. Beam scanning and capture of micro laser communication terminal based on MEMS micromirrors. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Wu, J. Adaptive compound control of laser beam jitter in deep-space optical communication systems. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 23228–23244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Oppenhauser, G. In-orbit test result of an operational optical intersatellite link between ARTEMIS and SPOT4, SILEX. Proc. SPIE 2002, 4635, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rüddenklau, R.; Rein, F.; Roubal, C.; Rödiger, B.; Schmidt, C. In-orbit demonstration of acquisition and tracking on OSIRIS4CubeSat. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 41188–41200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, E.A.; Bondurant, R.S. Fiber-based receiver for free-space coherent optical communication systems. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communication Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 6 February–9 June 1989; Optical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. paper THC5. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, R.; Hou, P.; Chen, W. Coupling method of space light to single-mode fiber based on laser nutation. Chin. J. Lasers 2016, 43, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Burnside, J.W.; Conrad, S.D.; Pillsbury, A.D.; DeVoe, C.E. Design of an inertially stabilized telescope for the LLCD. In Proceedings of the Free-Space Laser Communication Technologies XXIII, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–27 January 2011; Volume 7923, p. 79230L. [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe, C.E.; Pillsbury, A.D.; Khatri, F.; Burnside, J.M.; Raudenbush, A.C.; Petrilli, L.J.; Williams, T. Optical overview and qualification of the LLCD space terminal. In Proceedings of the SPIE International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2014, Tenerife, Spain, 6–10 October 2014; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10563, p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Hou, X.; Zhu, F.; Li, T.; Sun, J.; Zhu, R.; Gao, M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W. Experimental verification of coherent tracking system based on fiber nutation. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 23996–24008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, F.; Tan, L.Y.; Yu, S.; Han, Q. Plane wave coupling into single-mode fiber in the presence of random angular jitter. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 5184–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, X.; Yu, S.; Tan, L.Y. Influence of satellite vibration on optical communication performance for intersatellite laser links. Opt. Rev. 2012, 19, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Offset (rad) | Average Lateral Offset After Convergence (rad) | Coupling Efficiency Standard Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 6.8844 | 1.56 |

| 100 | 5.6032 | 1.34 |

| 150 | 4.6207 | 1.99 |

| 200 | 6.7450 | 1.11 |

| 250 | 6.0191 | 1.66 |

| 300 | 7.7056 | 1.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Peng, B.; Ma, C. Experimental Research of Inter-Satellite Beaconless Laser Communication Tracking System Based on Direct Fiber Control. Photonics 2025, 12, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121238

Zhao Y, Han J, Peng B, Ma C. Experimental Research of Inter-Satellite Beaconless Laser Communication Tracking System Based on Direct Fiber Control. Photonics. 2025; 12(12):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121238

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yue, Junfeng Han, Bo Peng, and Caiwen Ma. 2025. "Experimental Research of Inter-Satellite Beaconless Laser Communication Tracking System Based on Direct Fiber Control" Photonics 12, no. 12: 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121238

APA StyleZhao, Y., Han, J., Peng, B., & Ma, C. (2025). Experimental Research of Inter-Satellite Beaconless Laser Communication Tracking System Based on Direct Fiber Control. Photonics, 12(12), 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121238