Performance Evaluation of Black Phosphorus and Graphene Layers Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Antigens

Abstract

1. Introduction

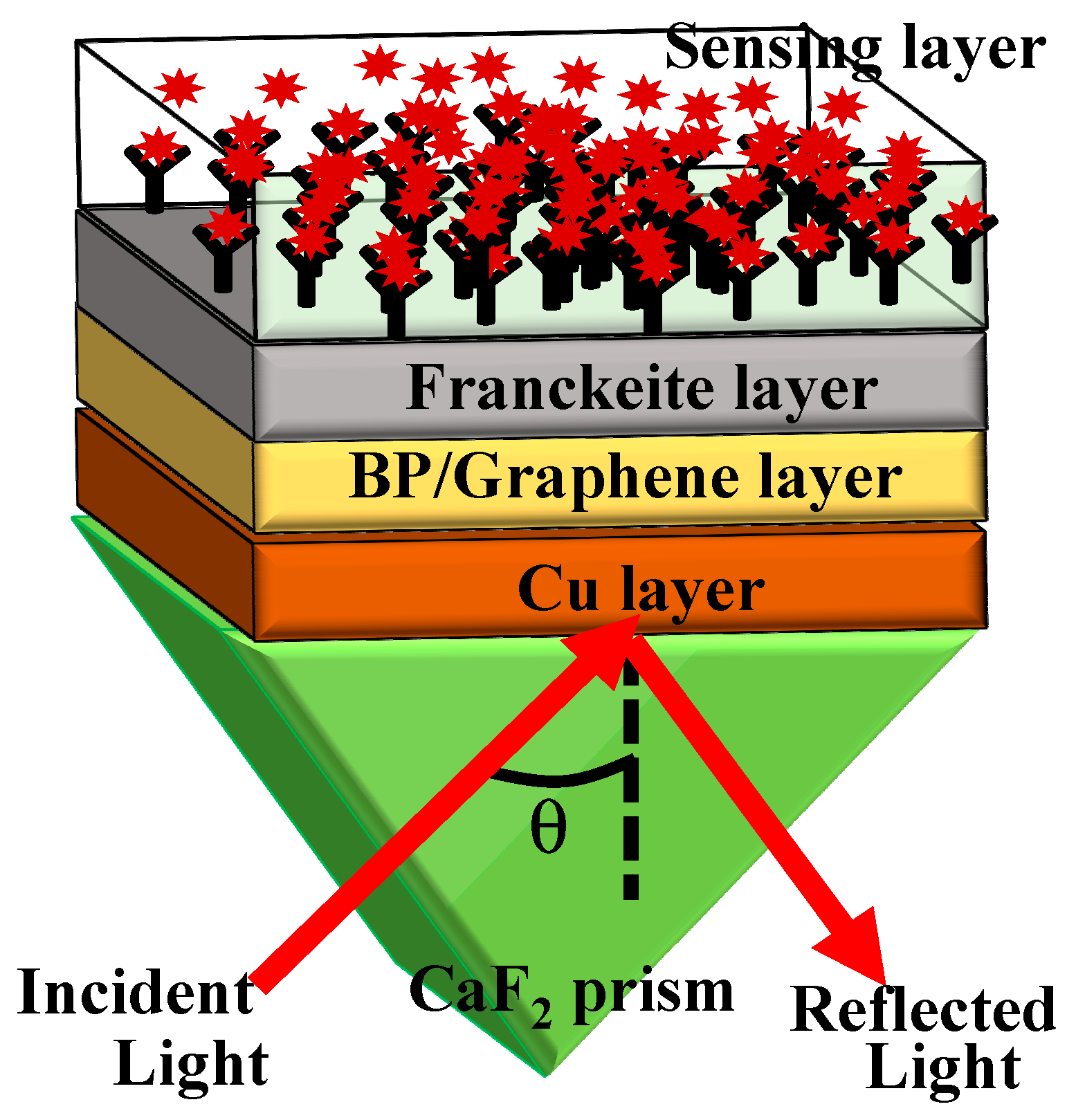

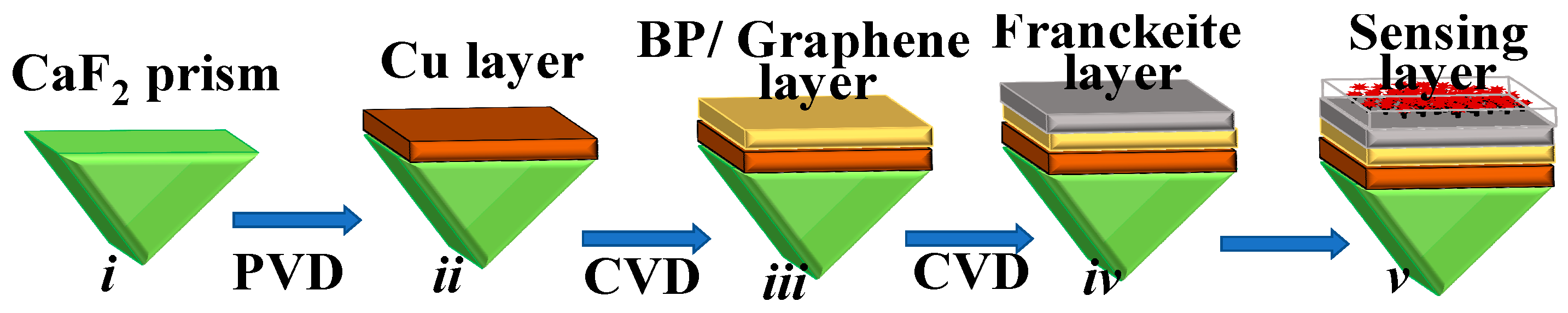

2. Proposed Structure, Fabrication Feasibility, Refractive Indices and Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

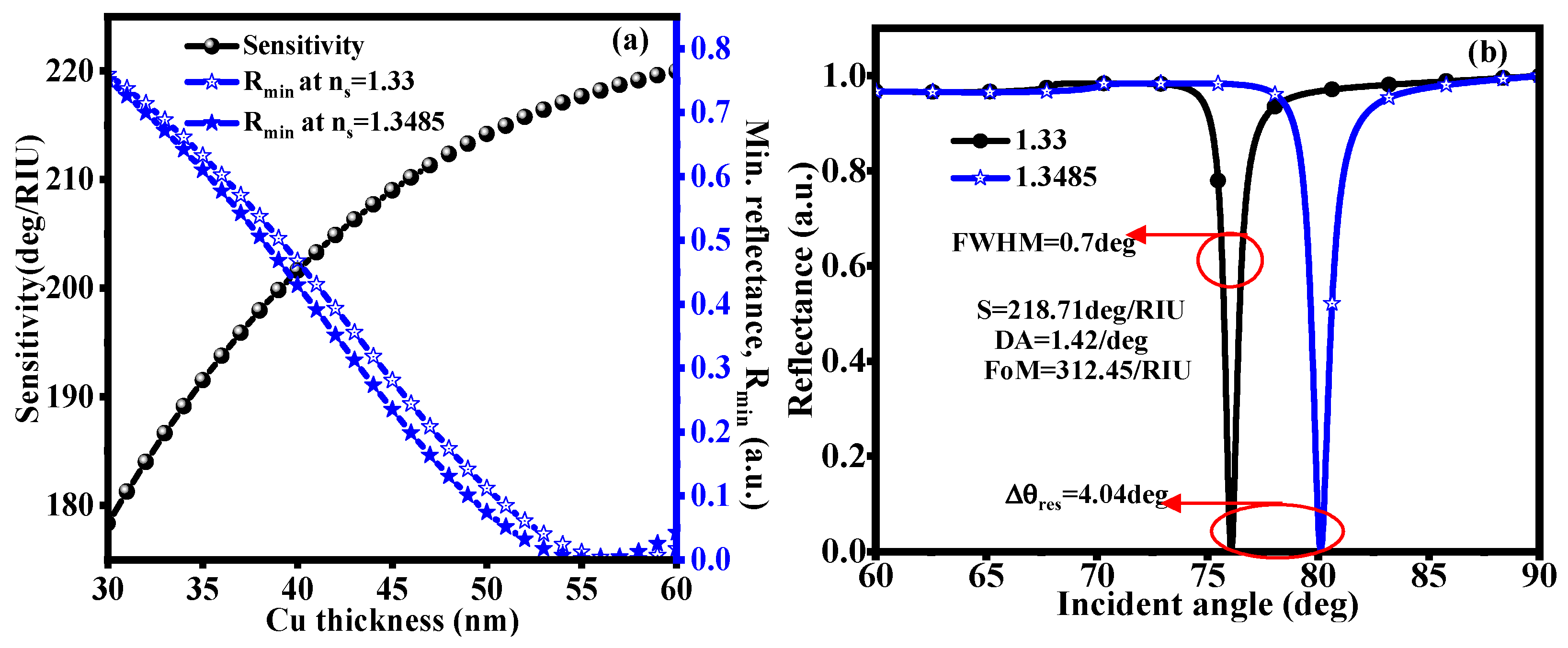

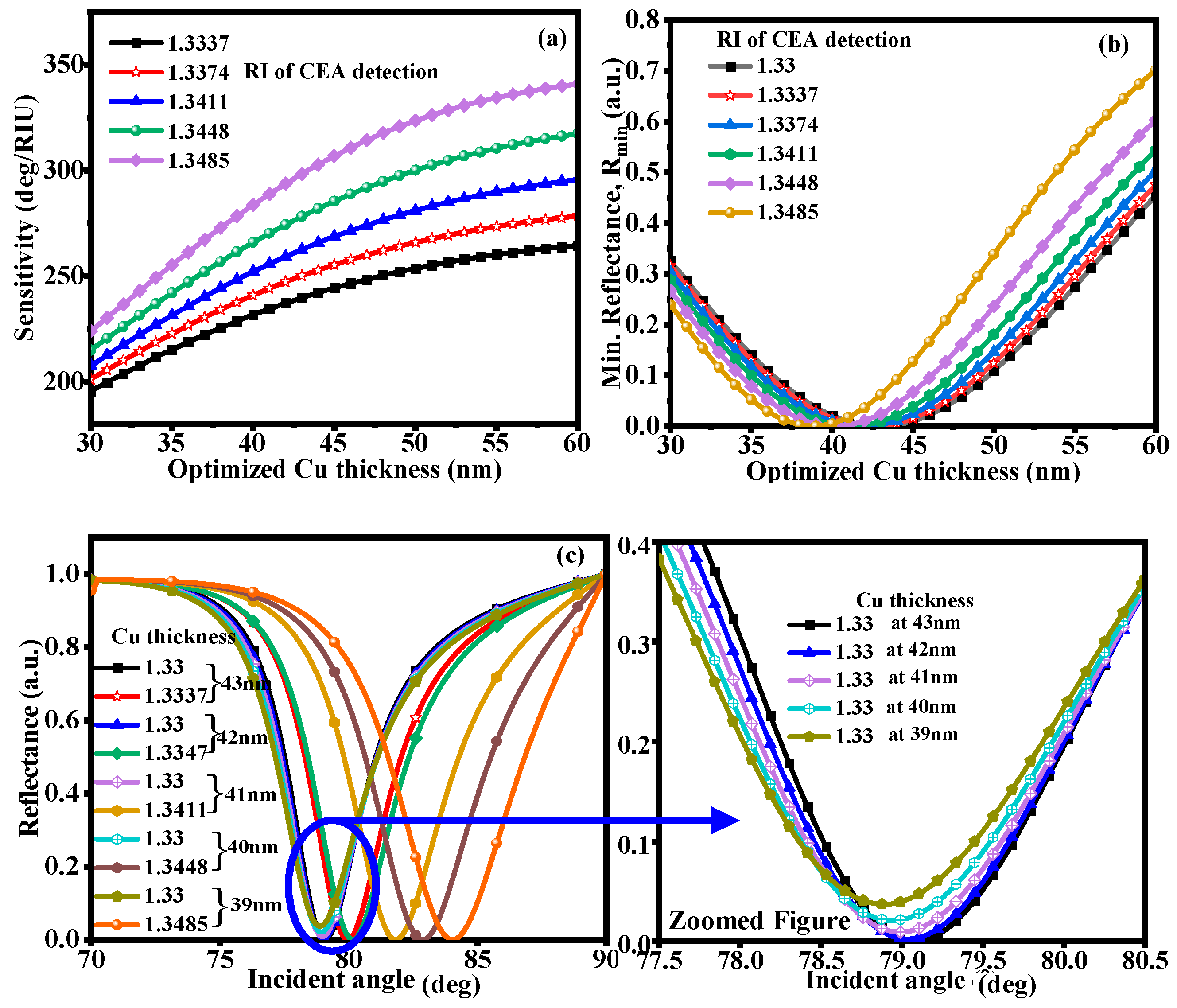

3.1. CaF2-Cu-SM

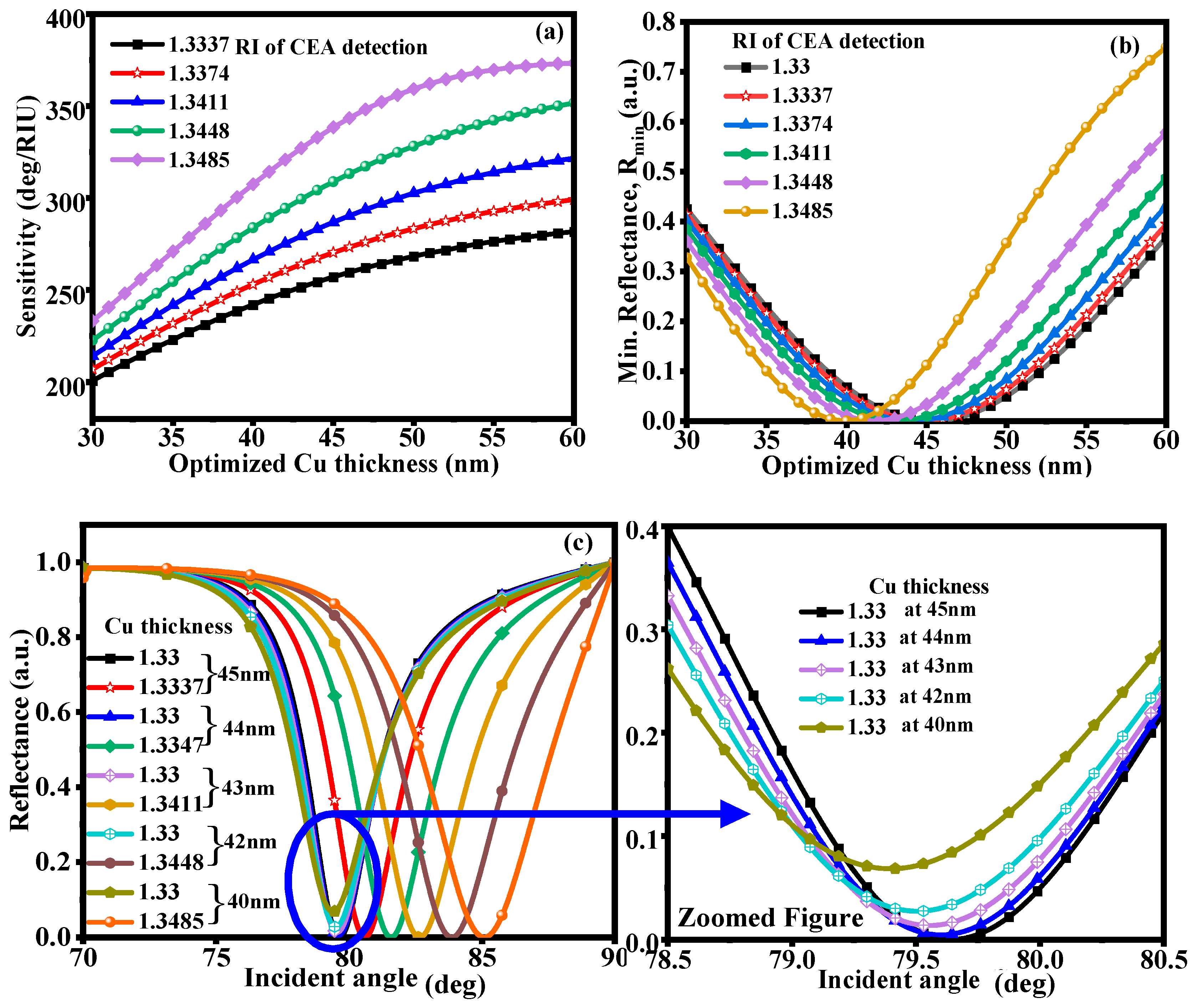

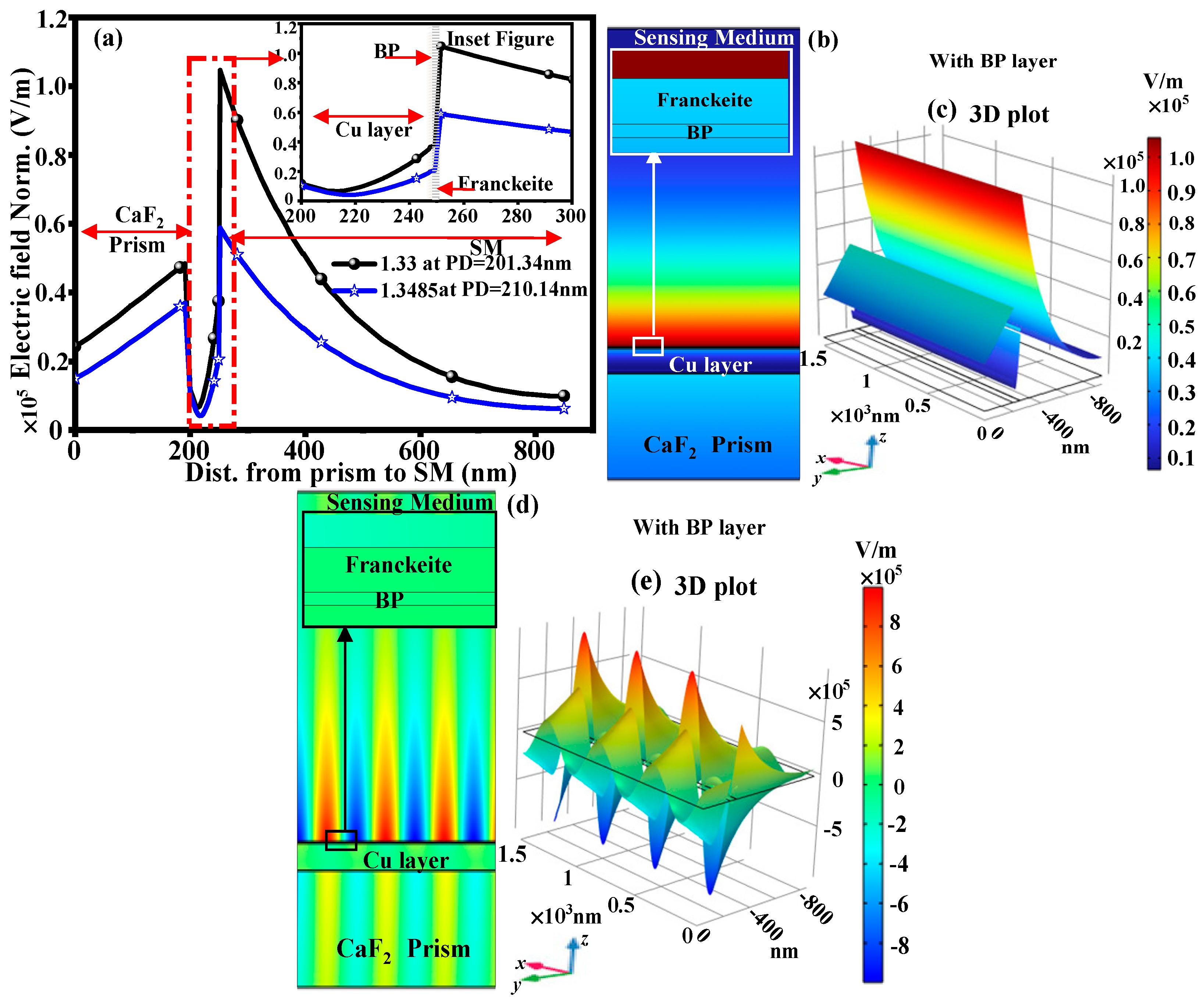

3.2. With Structure of CaF2-Cu-BP-Franckeite-SM

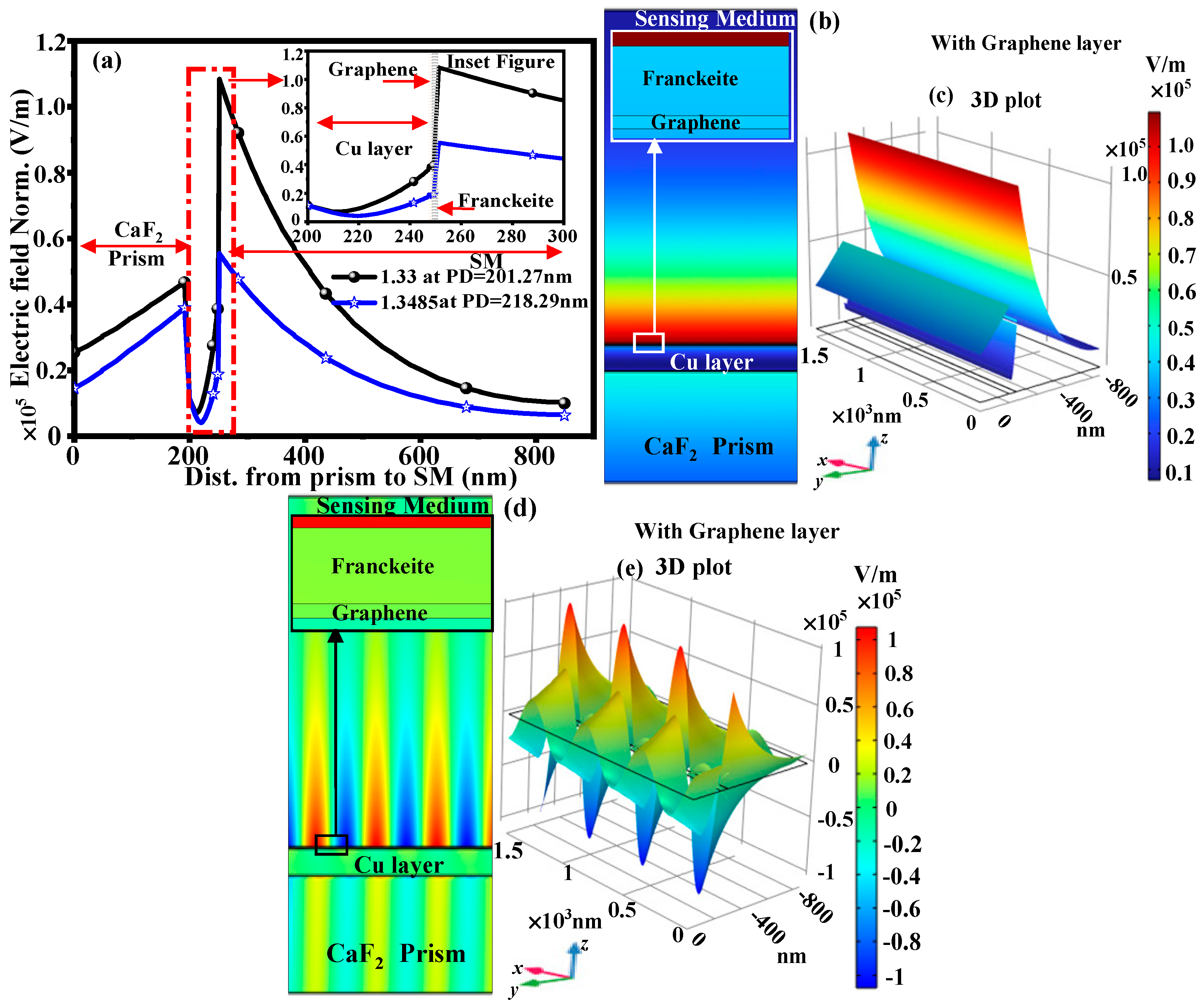

3.3. With Structure of CaF2-Cu-Graphene-Franckeite-SM

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hariri, M.; Alivirdiloo, V.; Ardabili, N.S.; Gholami, S.; Masoumi, S.; Mehraban, M.R.; Alem, M.; Hosseini, R.S.; Mobed, A.; Ghazi, F.; et al. Biosensor-Based Nanodiagnosis of Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA): An Approach to Classification and Precise Detection of Cancer Biomarker. Bionanoscience 2024, 14, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaie, A.; Heidarzadeh, H. Ultra-Sensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Integrating MXene (Ti3C2TX) and Graphene for Advanced Carcinoembryonic Antigen Detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasa, G.; Mascarenhas, R.J.; Malode, S.J.; Shetti, N.P. Graphene-Based Electrochemical Immunosensors for Early Detection of Oncomarker Carcinoembryonic Antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2022, 11, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.D.; Nihal, S.; Liu, Q.; Sarfo, D.; Sonar, P.; Izake, E.L. A Universal Stimuli-Responsive Biosensor for Disease Biomarkers through Their Cysteine Residues: A Proof of Concept on Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) Biomarker. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 393, 134208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, W.; Yuan, C. FTO, PIK3CB Serve as Potential Markers to Complement CEA and CA15-3 for the Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Medicine 2023, 102, E35361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafighirani, Y.; Bahador, H.; Javidan, J. Graphene-Based LSPR Sensors Enable Polarization-Independent Detection of CEA Antigens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhanparast, S.; Shahbazi-Derakhshi, P.; Soleymani, J.; Amiri-Sadeghan, A.; Herischi, A.; Chaparzadeh, N.; Aftabi, Y. A Novel Electrochemical Immunosensor Based on Biomaterials for Detecting Carcinoembryonic Antigen Biomarker in Serum Samples. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Kumar, S.; Kaushik, B.K. Recent Advancements in Optical Biosensors for Cancer Detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 197, 113805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damborský, P.; Švitel, J.; Katrlík, J. Optical Biosensors. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostufa, S.; Akib, T.B.A.; Rana, M.M.; Islam, M.R. Highly Sensitive TiO2/Au/Graphene Layer-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Cancer Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Weng, J. Graphene Enhances the Sensitivity of Fiber-Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 5478–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, D.; Lechuga, L.M. Optical Waveguide Biosensors. Photonics Sci. Found. Technol. Appl. 2015, 4, 323–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukundan, H.; Anderson, A.S.; Grace, W.K.; Grace, K.M.; Hartman, N.; Martinez, J.S.; Swanson, B.I. Waveguide-Based Biosensors for Pathogen Detection. Sensors 2009, 9, 5783–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, M.S. Fluorescence-Based Biosensors. Fundam. Biosens. Healthc. 2024, 1, 265–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.; Ferjani, H.; Alsaad, A.M.; Tavares, C.J.; Telfah, A.D. Modeling a Graphene-Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Cancer Detection. Plasmonics 2024, 20, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homola, J. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 462–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taya, S.A.; Daher, M.G.; Almawgani, A.H.M.; Hindi, A.T.; Zyoud, S.H.; Colak, I. Detection of Virus SARS-CoV-2 Using a Surface Plasmon Resonance Device Based on BiFeO3-Graphene Layers. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houari, F.; El Barghouti, M.; Mir, A.; Akjouj, A. Nanosensors Based on Bimetallic Plasmonic Layer and Black Phosphorus: Application to Urine Glucose Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Anower, M.S.; Hasan, M.R.; Hossain, M.B.; Haque, M.I. Design and Numerical Analysis of Highly Sensitive Au-MoS2-Graphene Based Hybrid Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor. Opt. Commun. 2017, 396, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisha, A.; Maheswari, P.; Subanya, S.; Anbarasan, P.M.; Rajesh, K.B.; Jaroszewicz, Z. Ag-Ni Bimetallic Film on CaF2 Prism for High Sensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Photonics Lett. Pol. 2021, 13, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthumanikkam, M.; Vibisha, A.; Lordwin Prabhakar, M.C.; Suresh, P.; Rajesh, K.B.; Jaroszewicz, Z.; Jha, R. Numerical Investigation on High-Performance Cu-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Biosensing Application. Sensors 2023, 23, 7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almawgani, A.H.M.; Sarkar, P.; Pal, A.; Srivastava, G.; Uniyal, A.; Alhawari, A.R.H.; Muduli, A. Titanium Disilicide, Black Phosphorus–Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Dengue Detection. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lin, C. Sensitivity Comparison of Graphene Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor with Au, Ag and Cu in the Visible Region. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 056503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zynio, S.A.; Samoylov, A.V.; Surovtseva, E.R.; Mirsky, V.M.; Shirshov, Y.M. Bimetallic Layers Increase Sensitivity of Affinity Sensors Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance. Sensors 2002, 2, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Verma, A.; Saini, J.P.; Prajapati, Y.K. Sensitivity Enhancement Using Silicon-Black Phosphorus-TDMC Coated Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor. IET Optoelectron. 2019, 13, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandaram, M.; Veeran, R.; Balasundaram, R.K.; Jaroszewicz, Z.; Jha, R.; Ebrahim, H.R.S.M. Hybrid Structured (Cu-BaTiO3-BP-Graphene) SPR Biosensor for Enhanced Performance. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, N.; Saharia, A.; Agarwal, A.; Ali, J.; Yupapin, P.; Singh, G. Modeling of Highly Sensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensor for Urine Glucose Detection. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2020, 52, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, S.K. A Study on Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Biomarker Using 2D Materials Graphene, Mxene and MoS2. Optik 2022, 258, 168885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaie, A.; Bahador, H.; Heidarzadeh, H. Development of a Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Based MXene (Ti3C2Tx) for the Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA). Plasmonics 2025, 20, 5867–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.X.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, X.; Wang, L.L.; Wen, S.C. Phase-Controlled Topological Plasmons in 1D Graphene Nanoribbon Array. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 123, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, B.L.; Nouri, J.M.; Brabazon, D.; Naher, S. Graphene and Derivatives–Synthesis Techniques, Properties and Their Energy Applications. Energy 2017, 140, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xia, S.; Xu, W.; Zhai, X.; Wang, L. Topological Plasmonically Induced Transparency in a Graphene Waveguide System. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 245420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaraiah, V.; Zeng, Q.; Long, Y.; Liu, Z. Black Phosphorus Nanosheets: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications. Small 2016, 12, 3480–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, J.E.; Inacio, G.J.; Batista, N.N.; Morais, W.P.; Menezes, M.G.; Zazo, J.A.; Casas, J.A.; Paz, W.S. Franckeite-Derived van Der Waals Heterostructure with Highly Efficient Photocatalytic NOx Abatement: Theoretical Insights and Experimental Evidences. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, O.J.; Walker, K.A.D. Graphene Functionalization for Biosensor Applications. Silicon Carbide Biotechnol. A Biocompatible Semicond. Adv. Biomed. Devices Appl. 2016, 2, 85–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Fan, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Mei, L. 2D Black Phosphorus–Based Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão, R.; Sofer, Z.; Luxa, J.; Pumera, M. Layered Franckeite and Teallite Intrinsic Heterostructures: Shear Exfoliation and Electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 16590–16599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Pal, S.; Prajapati, Y.K.; Kumar, S.; Saini, J.P. Sensitivity Improvement of a MXene- Immobilized SPR Sensor With Ga-Doped-ZnO for Biomolecules Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 6536–6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Pandey, V.K.; Singh, S.; Dhasarathan, V. Enhanced Angular Sensitivity of Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Based on Si-Ag-MXene Structure for Cortisol Application. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, S.; Dai, X.; Xiang, Y.; Fan, D. Sensitivity Enhancement by Using Few-Layer Black Phosphorus-Graphene/TMDCs Heterostructure in Surface Plasmon Resonance Biochemical Sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 249, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Verma, R.K. Graphene and beyond Graphene MoS2: A New Window in Surface-Plasmon-Resonance-Based Fiber Optic Sensing. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.; Sharma, S.; Singh, Y.; Pal, A. Sensitivity Enhancement of Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor with 2-D Franckeite Nanosheets. Plasmonics 2022, 17, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodrati, M.; Mir, A.; Farmani, A. Numerical Analysis of a Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Biosensor Using Molybdenum Disulfide, Molybdenum Trioxide, and MXene for the Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 132, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didar, R.F.; Vahed, H. Improving the Performance of High-Sensitivity Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor with 2D Nanomaterial Coating (BP-WS2) Based on Hybrid Structure: Theoretical Analysis. IET Optoelectron. 2023, 17, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollapalli, R.; Phillips, J.; Paul, P. Ultrasensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor with a Feature of Dynamically Tunable Sensitivity and High Figure of Merit for Cancer Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, A.; Pal, A.; Ansari, G.; Chauhan, B. Numerical Simulation of InP and MXene-Based SPR Sensor for Different Cancerous Cells Detection. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 2895–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Martials | Thickness (nm) | RI | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaF2 prism | Semi-Infinite | 1.4329 | [40] |

| Cu layer | 30–60 nm | 0.0369 + 4.5393 i | [39] |

| BP | 0.53 nm | 3.5 + 0.01 i | [41] |

| Graphene | 0.34 nm | 3 + 1.1491 i | [42] |

| Franckeite layer | 1.8 nm | 3.53 + 0.39 i | [43] |

| CEA detection | - | 1.33 (Reference RI) −1.3485 | [7] |

| RI of CEA | Cu Thick. (nm) | S (deg/RIU) | Rmin (a.u.) | FWHM (deg) | DA (/deg) | FoM (RIU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3337 | 45 | 257.05 | 6.56 × 10−5 | 3.27 | 0.305 | 78.61 |

| 1.3374 | 44 | 267.19 | 3.35 × 10−5 | 3.61 | 0.277 | 74.01 |

| 1.3411 | 43 | 279.30 | 5.08 × 10−5 | 4 | 0.25 | 69.82 |

| 1.3448 | 42 | 294.45 | 1.6 × 10−4 | 4.44 | 0.225 | 66.31 |

| 1.3485 | 40 | 307.50 | 4.20 × 10−5 | 4.99 | 0.200 | 61.62 |

| RI of CEA | Cu Thick. (nm) | S (deg/RIU) | Rmin (a.u.) | FWHM (deg) | DA (/deg) | FoM (RIU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3337 | 43 | 239.71 | 6.4 × 10−4 | 3.87 | 0.258 | 61.94 |

| 1.3374 | 42 | 247.22 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 3.92 | 0.255 | 63.06 |

| 1.3411 | 41 | 255.81 | 6.9 × 10−5 | 4.46 | 0.224 | 57.35 |

| 1.3448 | 40 | 265.99 | 7.4 × 10−5 | 4.88 | 0.204 | 54.50 |

| 1.3485 | 39 | 278.36 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 5.31 | 0.188 | 52.42 |

| RI of CEA | With BP Layer | With Graphene Layer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu Thick. (nm) | S (deg/RIU) | Rmin (a.u.) | Cu Thick. (nm) | S (deg/RIU) | Rmin (a.u.) | |

| 1.3337 | 56 | 277.65 | 0.248 | 53 | 257.98 | 0.223 |

| 1.3374 | 55 | 292.75 | 0.246 | 52 | 269.29 | 0.214 |

| 1.3411 | 53 | 309.81 | 0.224 | 51 | 283.12 | 0.216 |

| 1.3448 | 51 | 331.42 | 0.229 | 50 | 300.10 | 0.236 |

| 1.3485 | 47 | 348.07 | 0.203 | 47 | 314.32 | 0.207 |

| Authors and Ref. | Sensitivity (deg/RIU) | FoM/Quality Factor (/RIU) | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al. [29] | 144.72 | - | 2022 |

| Ghodrati et al. [44] | 227.08 | 35.09 | 2023 |

| Didar et al. [45] | 234 | 26.53 | 2023 |

| Gollapalli et al. [46] | 329.1 | 89.81 | 2023 |

| Khodaie et al. [2] | 163.63 | 17.52 | 2025 |

| Khodaie et al. [30] | 196.91 | 14.87 | 2025 |

| Uniyal et al. [47] | 263.57 | 34.62 | 2025 |

| Proposed Work | 348.32 | 93.06 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Yun, T.S.; Sain, M. Performance Evaluation of Black Phosphorus and Graphene Layers Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Antigens. Photonics 2025, 12, 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111105

Kumar R, Kumar P, Yun TS, Sain M. Performance Evaluation of Black Phosphorus and Graphene Layers Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Antigens. Photonics. 2025; 12(11):1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111105

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Rajeev, Prem Kumar, Tae Soo Yun, and Mangal Sain. 2025. "Performance Evaluation of Black Phosphorus and Graphene Layers Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Antigens" Photonics 12, no. 11: 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111105

APA StyleKumar, R., Kumar, P., Yun, T. S., & Sain, M. (2025). Performance Evaluation of Black Phosphorus and Graphene Layers Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of CEA Antigens. Photonics, 12(11), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111105