Fresnel Coherent Diffraction Imaging Without Wavefront Priors

Abstract

1. Introduction

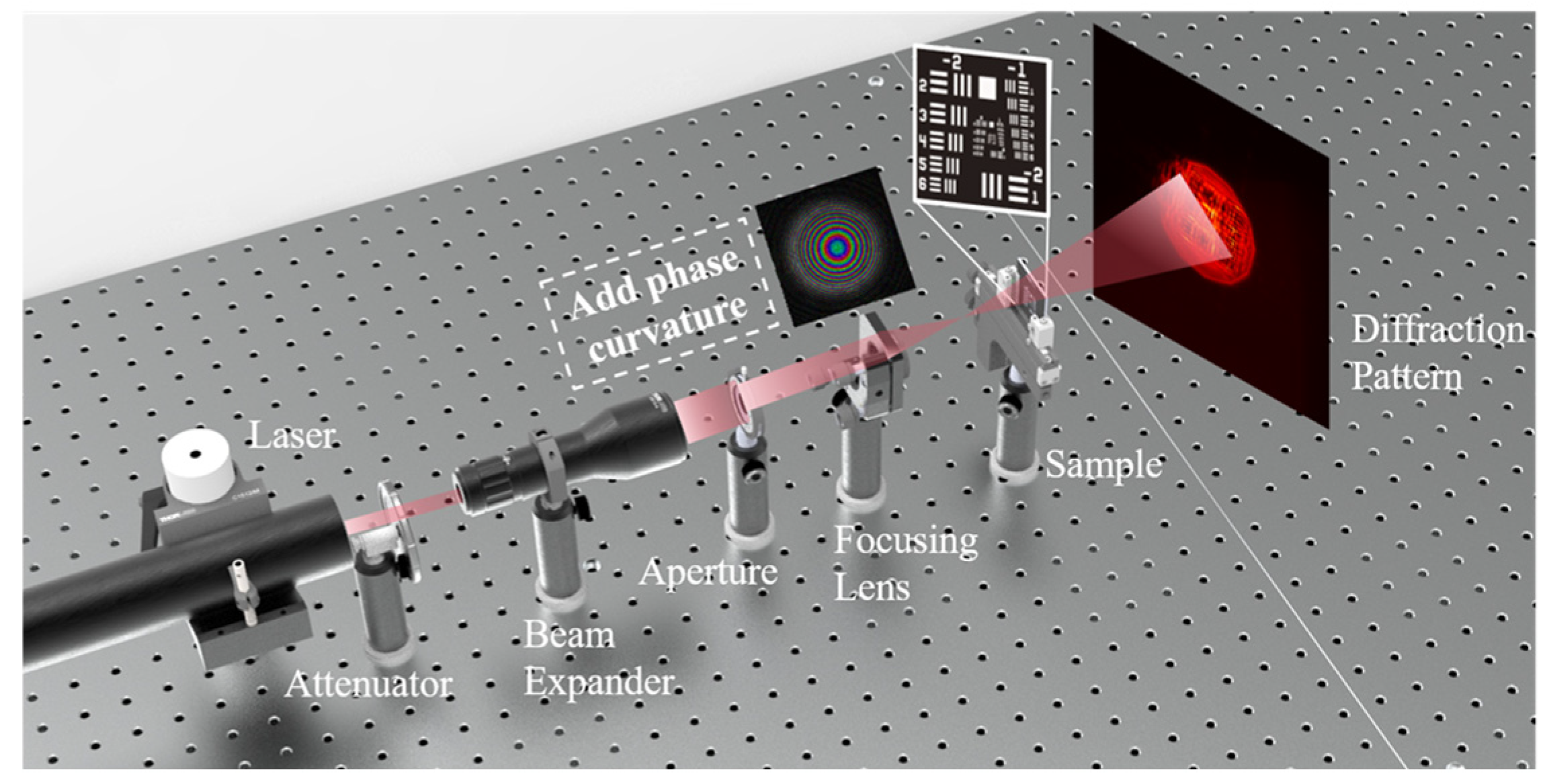

2. Materials and Methods

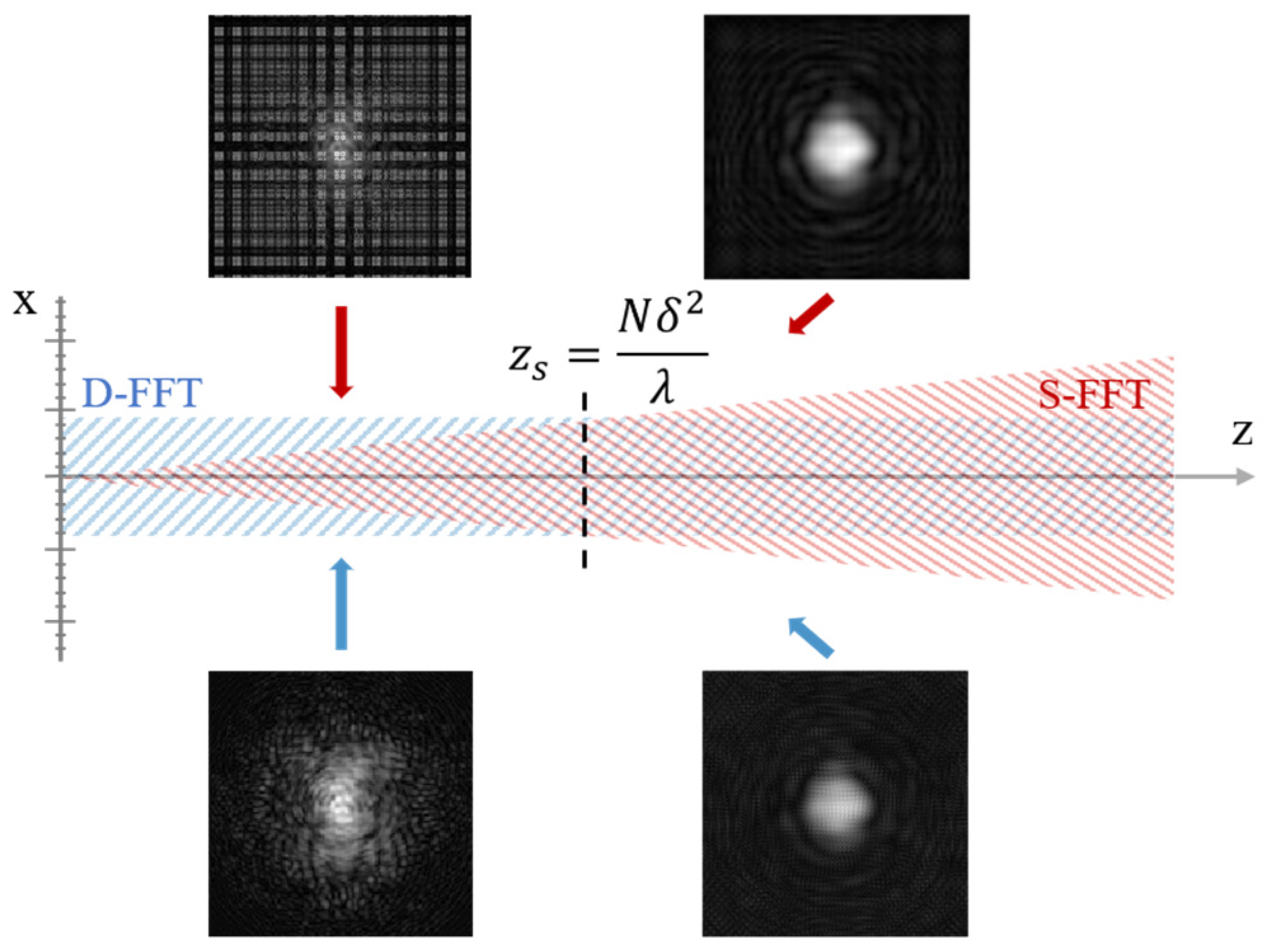

2.1. Diffraction Calculation

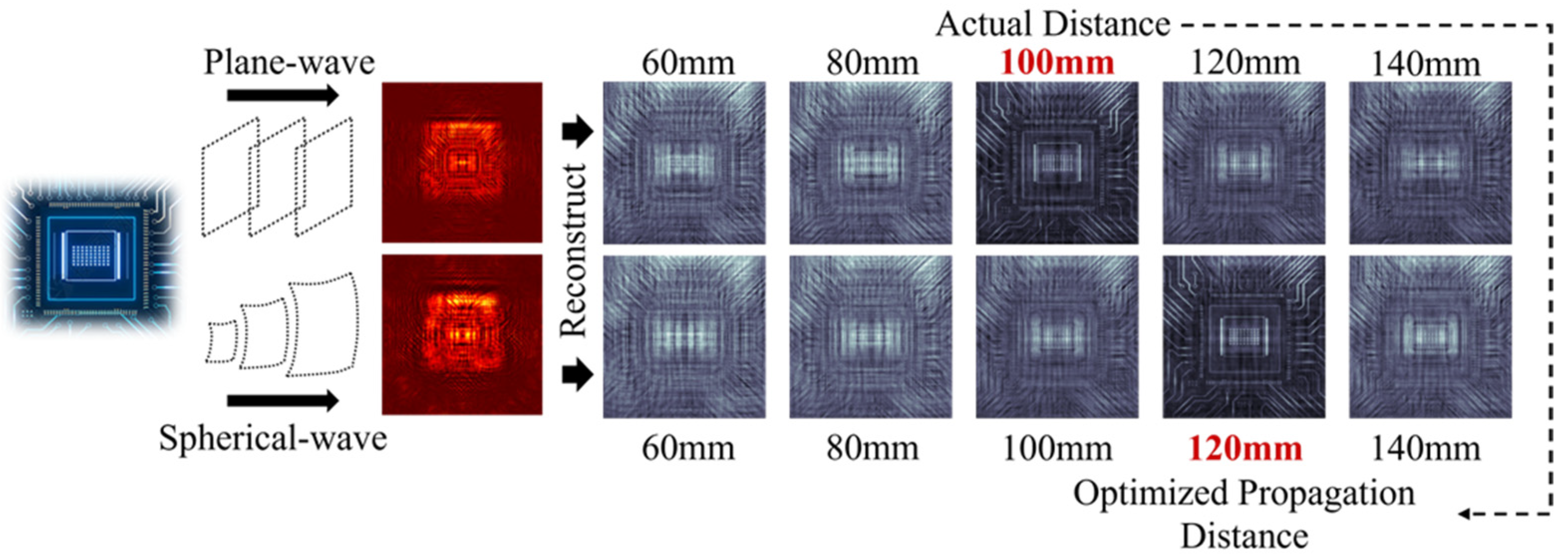

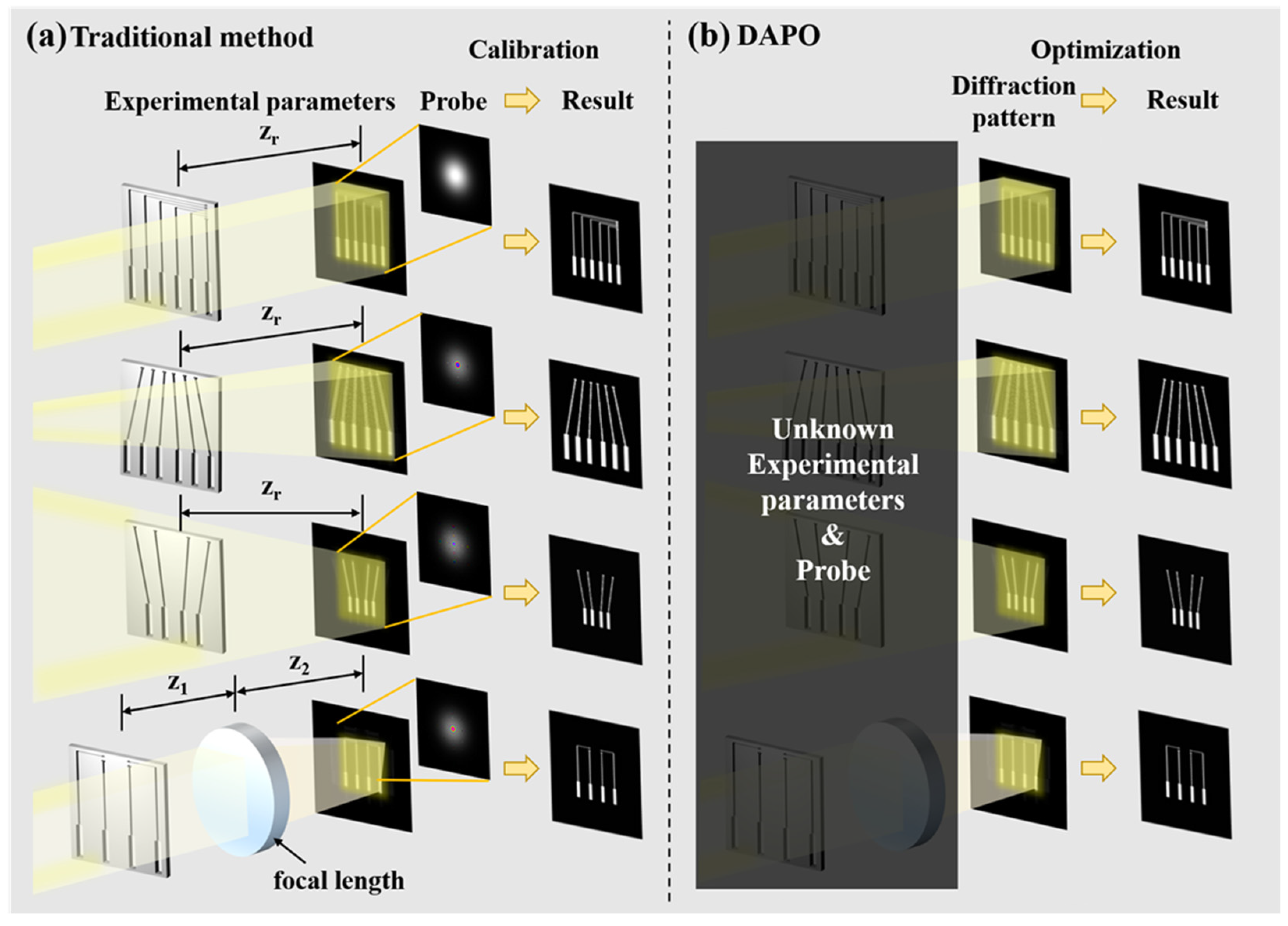

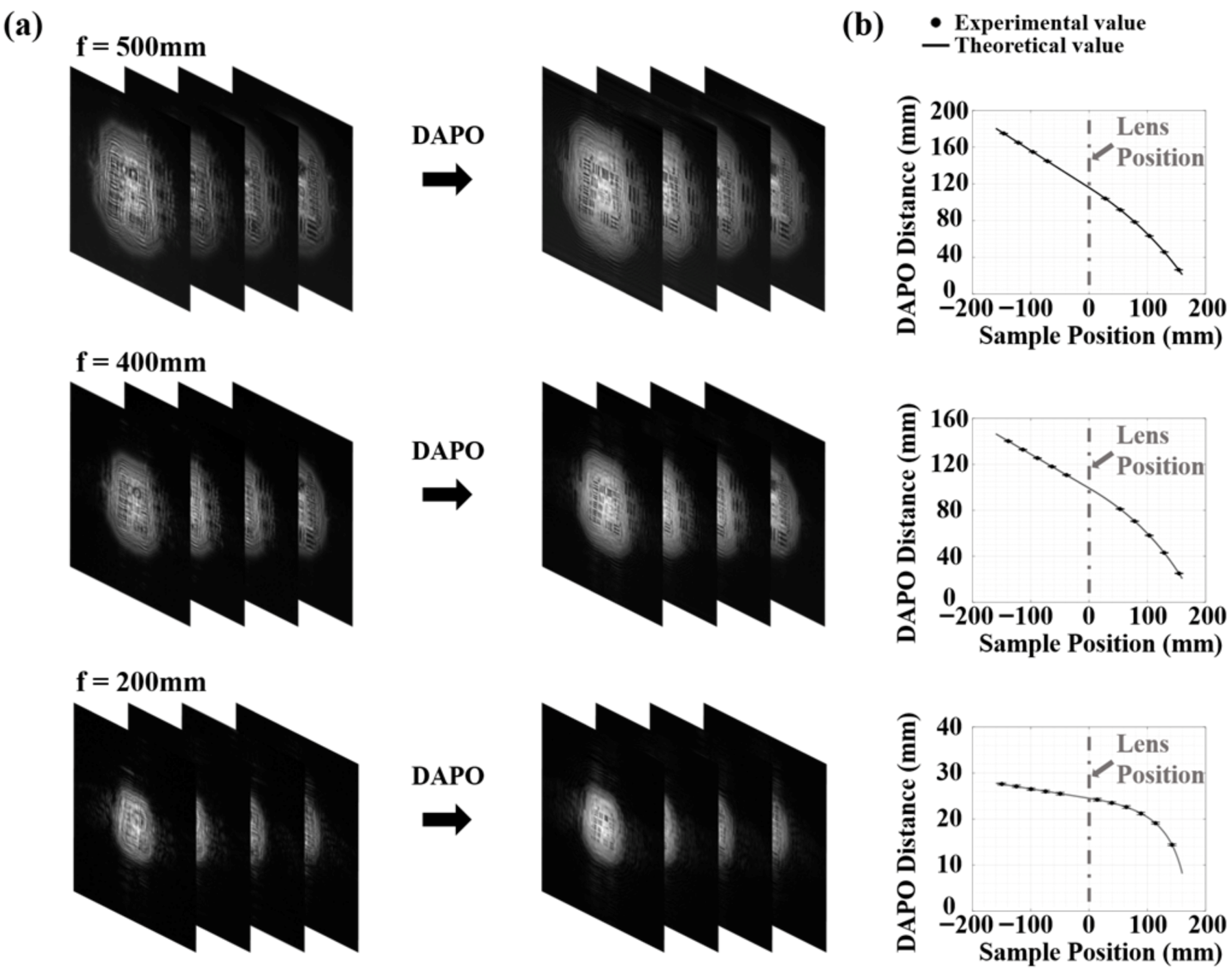

2.2. Diffraction-Adapted Propagation Optimization

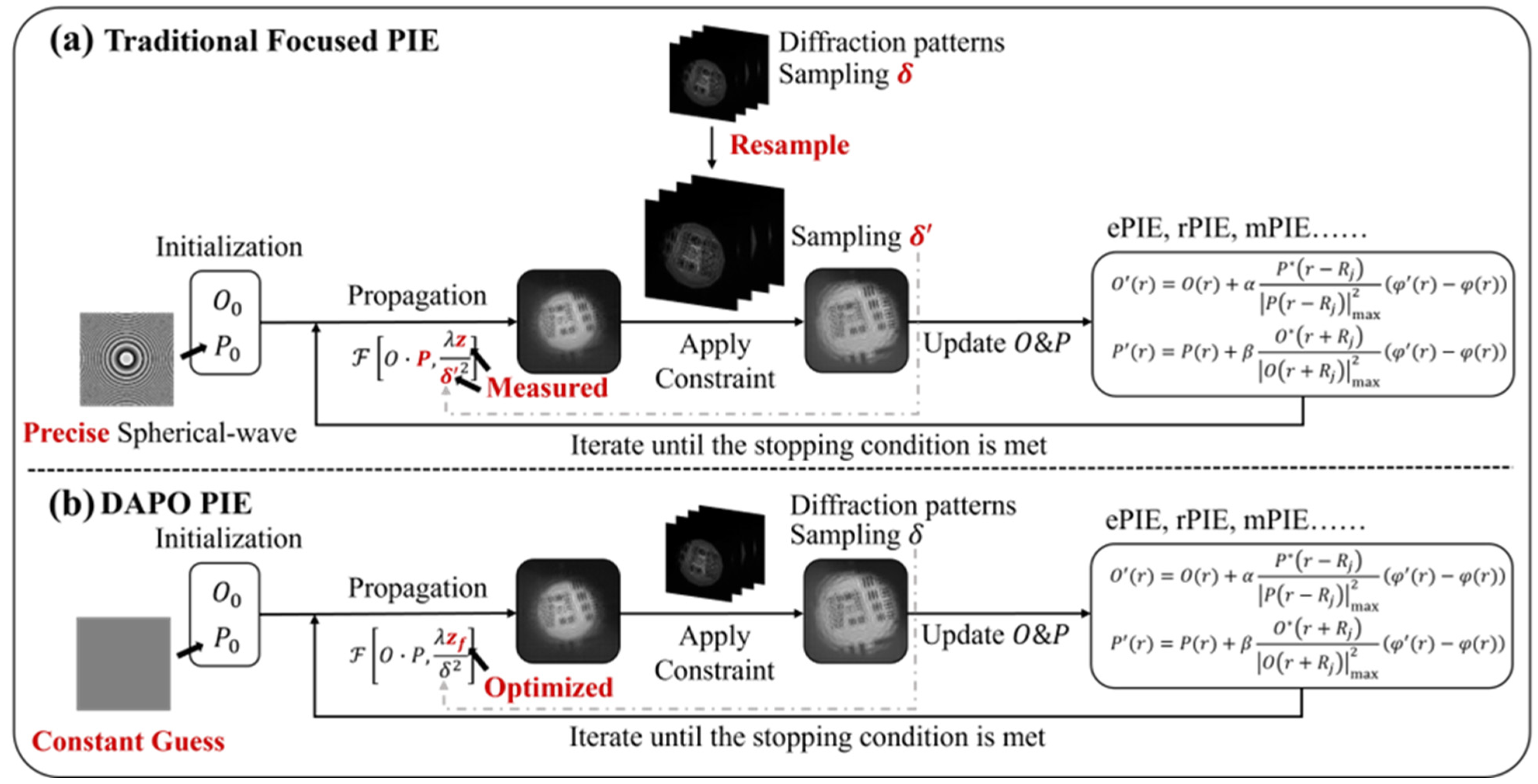

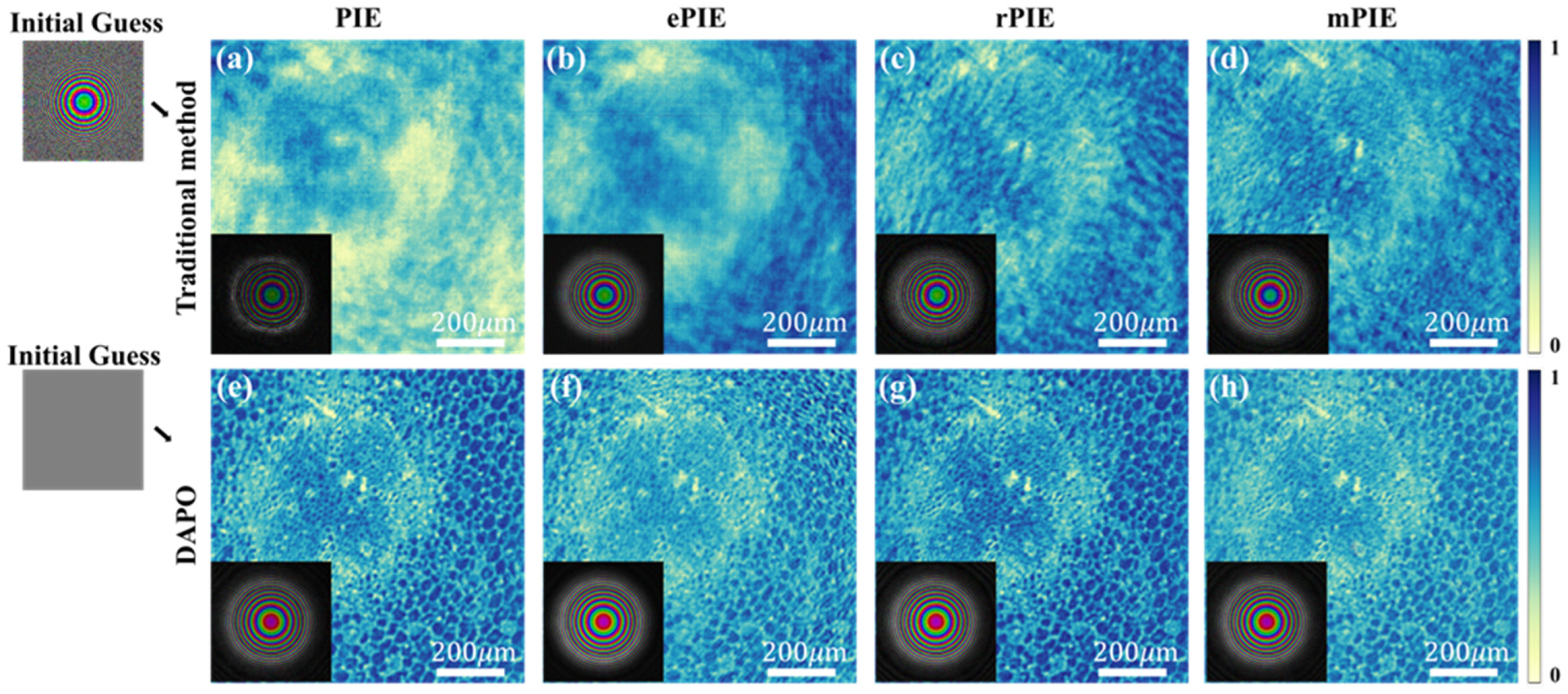

2.3. Comparison of the Ptychographic Reconstruction Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, J.L.; Barnes, C.W.; Sandberg, R.L.; Sheffield, R.L. Diffractive imaging at large Fresnel number: Challenge of dynamic mesoscale imaging with hard x rays. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 184105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, I.; Abbey, B.; Putkunz, C.T.; Vine, D.; van Riessen, G.; Cadenazzi, G.; Balaur, E.; Ryan, R.; Quiney, H.; McNulty, I.; et al. Nanoscale Fresnel coherent diffraction imaging tomography using ptychography. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 24678–24685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.W.M.; van Riessen, G.A.; Abbey, B.; Putkunz, C.T.; Junker, M.D.; Balaur, E.; Vine, D.J.; McNulty, I.; Chen, B.; Arhatari, B.D.; et al. Whole-cell phase contrast imaging at the nanoscale using Fresnel Coherent Diffractive Imaging Tomography. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.J.; Quiney, H.M.; Dhal, B.B.; Tran, C.Q.; Nugent, K.A.; Peele, A.G.; Paterson, D.; de Jonge, M.D. Fresnel coherent diffractive imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 025506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.J.; Quiney, H.M.; Peele, A.G.; Nugent, K.A. Fresnel coherent diffractive imaging: Treatment and analysis of data. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 035020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, K.A.; Peele, A.G.; Quiney, H.M.; Chapman, H.N. Diffraction with wavefront curvature: A path to unique phase recovery. Found. Crystallogr. 2005, 61, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, K.A.; Peele, A.G.; Chapman, H.N.; Mancuso, A.P. Unique phase recovery for nonperiodic objects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 203902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, B.; Nugent, K.A.; Williams, G.J.; Clark, J.N.; Peele, A.G.; Pfeifer, M.A.; de Jonge, M.; McNulty, I. Keyhole coherent diffractive imaging. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, L.; Neupane, C.; Balodhi, A.; Bista, S.; Butun, S.; Jangid, R.; Barbour, A.; Basit, N.; Agterberg, D.F.; Weinert, M.; et al. Fresnel diffraction imaging of surface nanostructure using coherent resonant x-ray scattering. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 138, 013902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A. Analytical and numerical fresnel models of phase diffractive optical elements for imaging applications. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Diebold, G.J. Determination of Fresnel Integrals for X-ray Phase Contrast Imaging with the Fast Fourier Transform. Microsc. Microanal. 2025, 31 (Suppl. S1), ozaf048.1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiney, H.M.; Peele, A.G.; Cai, Z.; Paterson, D.; Nugent, K.A. Diffractive imaging of highly focused X-ray fields. Nat. Phys. 2006, 2, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Gao, Z.; Ma, J.; Yuan, C.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L. Iterative autofocusing strategy for axial distance error correction in ptychography. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017, 98, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Bai, L.; Xu, Y.; Kuang, C.; Liu, X. Fast autofocusing strategy for phase retrieval based on statistical gradient optimization. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 184, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, J.; Shao, Y.; van Dam, R.; Bouchet, D.; van Leeuwen, T.; Mosk, A.P. Maximum-likelihood estimation in ptychography in the presence of Poisson–Gaussian noise statistics. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 6027–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Yang, D.; Yu, T.; Li, T.; Sun, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y. Sharpness-statistics-based auto-focusing algorithm for optical ptychography. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2020, 128, 106053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loetgering, L.; Du, M.; Eikema, K.S.E.; Witte, S. zPIE: An autofocusing algorithm for ptychography. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 2030–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, D.; Garcia, J.; Ferreira, C.; Bernardo, L.M.; Marinho, F. Fast algorithms for free-space diffraction patterns calculation. Opt. Commun. 1999, 164, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganin, D. Coherent X-Ray Optics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, J.M. Diffraction Physics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mendlovic, D.; Zalevsky, Z.; Konforti, N. Computation considerations and fast algorithms for calculating the diffraction integral. J. Mod. Opt. 1997, 44, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yoo, S.; Chu, Y.S.; Huang, X.; Robinson, I.K. Dose-efficient automatic differentiation for ptychographic reconstruction. Optica 2024, 11, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, J.M.; Faulkner, H.M.L. A phase retrieval algorithm for shifting illumination. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 4795–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, H.M.L.; Rodenburg, J.M. Movable aperture lensless transmission microscopy: A novel phase retrieval algorithm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 023903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiden, A.M.; Rodenburg, J.M. An improved ptychographical phase retrieval algorithm for diffractive imaging. Ultramicroscopy 2009, 109, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, A.; Johnson, D.; Li, P. Further improvements to the ptychographical iterative engine. Optica 2017, 4, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhong, L.; Gong, M.; Du, J.; Gu, H.; Liu, S. An efficient and robust self-calibration algorithm for translation position errors in ptychography. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Veetil, S.P.; He, X.; Sun, A.; Jiang, Z.; Kong, Y.; Liu, C. Mitigating reconstruction errors in extended-ptychography with adaptive scanning position correction. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, M.; Darudi, A.; Moradi, A.R. Digital in-line holography for wavefront sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 180, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Nie, J.; Xue, T.; Gu, J. Learning-based lens wavefront aberration recovery. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 18931–18943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorin, P.A.; Dzyuba, A.P.; Khonina, S.N. Optical wavefront aberration: Detection, recognition, and compensation techniques–A comprehensive review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 191, 113342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, I.; Wakunami, K.; Ichihashi, Y.; Oi, R. Wavefront-aberration-tolerant diffractive deep neural networks using volume holographic optical elements. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image Size | mPIE(s) | mPIE + DAPO(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 512 × 512 | 52.8 | 15.7 |

| 1024 × 1024 | 181.8 | 30.2 |

| 2048 × 2048 | 3403.6 | 72.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, L.; Cao, W.; Xu, Y.; Kuang, C.; Liu, X. Fresnel Coherent Diffraction Imaging Without Wavefront Priors. Photonics 2025, 12, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111066

Bai L, Cao W, Xu Y, Kuang C, Liu X. Fresnel Coherent Diffraction Imaging Without Wavefront Priors. Photonics. 2025; 12(11):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111066

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Ling, Wen Cao, Yueshu Xu, Cuifang Kuang, and Xu Liu. 2025. "Fresnel Coherent Diffraction Imaging Without Wavefront Priors" Photonics 12, no. 11: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111066

APA StyleBai, L., Cao, W., Xu, Y., Kuang, C., & Liu, X. (2025). Fresnel Coherent Diffraction Imaging Without Wavefront Priors. Photonics, 12(11), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12111066