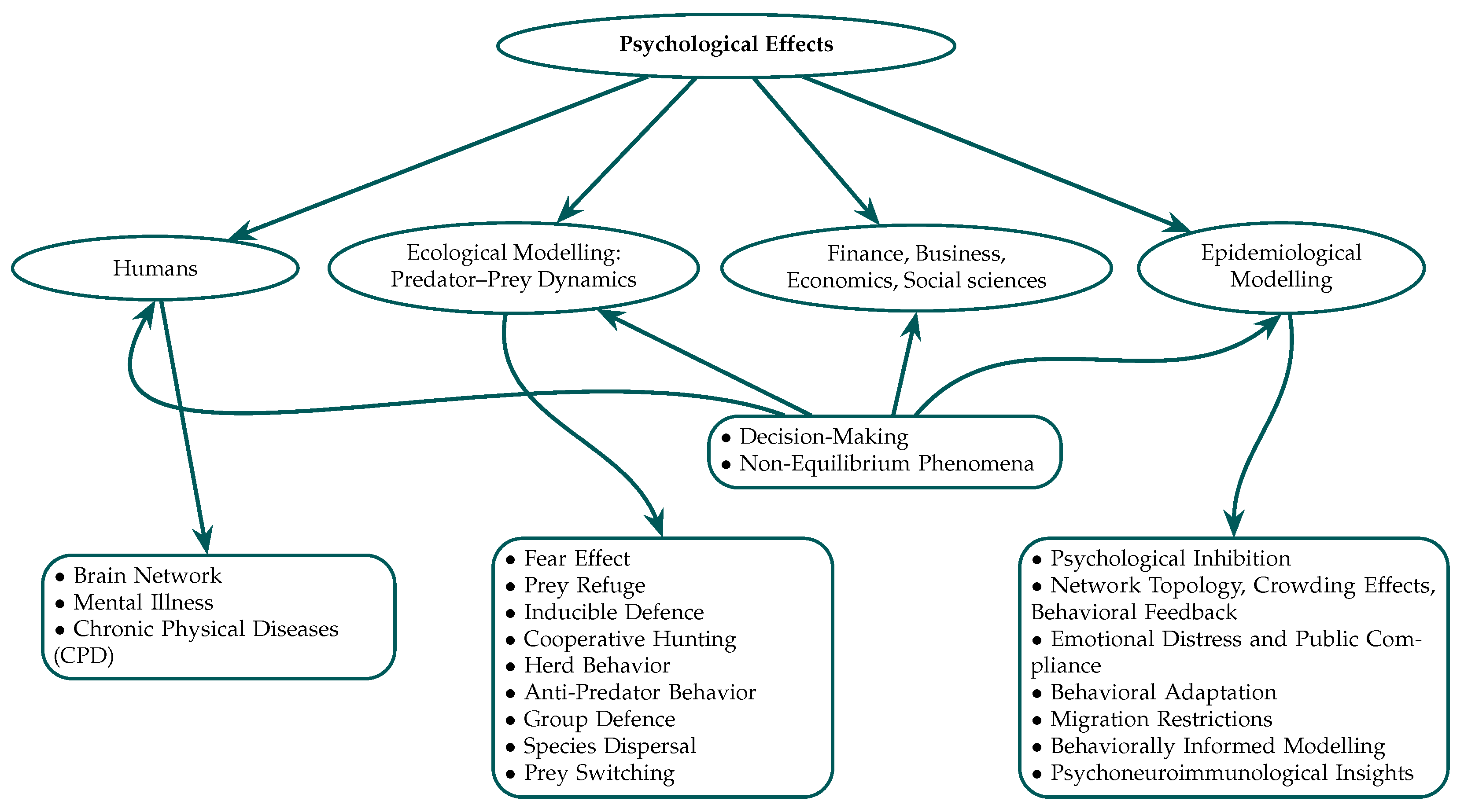

Integrating Emotion-Specific Factors into the Dynamics of Biosocial and Ecological Systems: Mathematical Modeling Approaches Accounting for Psychological Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Effects of Different Psychological Factors on Humans

2.1. Psychological Effects on Brain Networks

2.1.1. Large-Scale Brain Networks and Emotional Modulation

2.1.2. Metabolic Constraints and Generative Modeling

2.1.3. Emotion-Induced Collective Dynamics and Crowd Behavior

2.1.4. Emotion and Decision-Making: Drift-Diffusion Models (DDMs)

2.1.5. Advances in Psychophysics, Signal Processing, and Computational Emotion

2.1.6. Stochastic Modeling of Emotional Dynamics

2.2. Psychological Effects on Mental Illness

2.2.1. Stigma, Cognitive Appraisals, and Social Context

2.2.2. Illness Perceptions and Emotional Regulation

2.2.3. Physiological and Developmental Mechanisms

2.2.4. Mathematical and Computational Modeling of Psychopathology

2.2.5. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Mathematical Representations

2.2.6. Emerging Therapies and Neurocomputational Developments

2.3. Psychological Factors in Chronic Physical Diseases (CPDs)

2.3.1. Bidirectional Links Between CPDs and Psychological Distress

2.3.2. Mathematical and Computational Perspectives on Emotional Regulation in CPDs

2.3.3. Cognitive Deficits and Pain Amplification Mechanisms

2.3.4. Developmental, Psychosocial, and Neurobiological Contributors

2.3.5. Role of AI and Emotional Computing in CPD Management

2.3.6. Psychological Interventions and Interdisciplinary Care

3. Similarities and Differences in Model Formulation: Human and Animal Psychology

3.1. Shared Mathematical Foundations

3.2. Animal Psychology Modeling

3.3. Human Psychology Modeling

3.4. Neurophysiological Integration

4. Psychological Effects in Ecological Modeling: From the Perspective of Predator–Prey Interactions

4.1. Fear Effect on Prey

4.2. Prey Refuge

- (i)

- Refuge proportional to the prey population:

- (ii)

- Constant refuge population:

- (iii)

- Refuge proportional to the predator population:

- (iv)

- Refuge proportional to both prey and predator population:

4.3. Inducible Defense

4.4. Cooperative Hunting

4.5. Herd Behavior

4.6. Anti-Predator Behavior

4.7. Group Defense

4.8. Population Dispersal/Migration

4.9. Prey Switching by Looking for Alternative Food Sources

5. Psychological Effects in Epidemiological Modeling

- Psychological inhibition and modified incidence rates: People generally respond to epidemic problems by making psychological changes that help them avoid contact with others and stop the spread of the disease [581,582,583]. These modifications, which range from social disengagement to improved hygiene, necessitate adjustments to the normal bilinear incidence rates, typically represented as in SIR/SEIR models [584,585,586,587,588,589]. Subsequently, epidemiological studies utilized a nonlinear incidence rate [590,591,592,593,594]. Capasso and Serio proposed a saturated incidence rate to reflect behavioral inhibition [595]:where k and are constants, measures the infection force, and reflects the reduction in contact due to psychological inhibition as infection prevalence increases [583,596]. This functional form is mostly phenomenological, despite its widespread use in classical epidemic modeling. Its empirical validation is largely derived from initial short-term outbreak findings, and its repeatability across diverse populations or long-term behavioral responses is still constrained. So, even if it does a good job of capturing monotonic behavioral inhibition, its generalizability is limited by how simple its assumptions are. This was further generalized to nonmonotonic forms, such as [597], capturing the ‘psychological effect’ in response to infection prevalence. Nonetheless, numerous extensions depend predominantly on simulation-based validation and are deficient in extensive empirical calibration. Consequently, the scope and duration of the inferred psychological effects exhibit significant variability across research, and their consistency across other disorders or temporal intervals are yet to be definitively determined. Subsequent research elucidates the impact of psychological inhibition on illness suppression by including information-induced behavioral alteration [598] and optimal control strategies, such as social distancing and heightened awareness [599]. These models have conceptual viability; nevertheless, as to previous formulations, their behavioral elements are predominantly substantiated through theoretical frameworks rather than replicated empirical datasets, hence constraining their resilience.

- Network topology, crowding effects, and behavioral feedback: Other types of studies have looked at how the structure of a network influences how people act and how information spreads [600,601,602,603,604]. Research on business and communication networks shows that topological features like connectivity and clustering affect how users operate and how viruses spread. In particular, crowding effects in point-to-group (P2G) network sharing might inhibit the transmission of viruses by causing delays and withdrawal behavior when people feel threatened [605]. It is important to note that many of these behavioral consequences are only replicated under certain or idealized network assumptions, which makes it unclear how well they apply to real-world systems that are not homogeneous [606]. Controlling a virus depends extensively on psychological factors, such as disconnecting from infected nodes [607]. Using a modified incidence rate, Yuan et al. created a nonlinear e-SEIR model including crowding and behavioral inhibition [608]:thereby integrating user connectivity to psychological feedback. Here, captures virus transmission influenced by user connectivity, and reflects psychological inhibition as infections rise. Behavioral inhibition increases with the number of infectives and is influenced by network-driven exposure patterns. This model’s behavioral modulation is closely linked to network structure, which makes its predictions very sensitive to assumptions about topology and how users interact with each other. This is different from the standard saturated incidence form. Its validation relies predominantly on simulations, and evidence supporting its replication outside of stylized networks is still scarce.Bellomo et al. proposed a multi-scale modeling framework for behavioral human crowds, underscoring the necessity of emotional states, varied strategic planning, and nonlinear social interactions [458]. Their incorporation of ‘activity’ as a dynamic behavioral variable facilitates a nuanced examination of group-level responses shaped by individual psychological traits, augmenting the understanding of crowd-mediated behavioral feedback during epidemics. Similarly, a fractional-order SIRS model incorporating memory-driven vaccination behavior captures nonlinear reactions to public health communications [609]. Network-level behavioral interactions and awareness of HIV preventive methods, such as PrEP, similarly influence epidemic patterns [610]. These differences reveal that both formulations in (28) and (29) represent psychological inhibition, but they are very different in terms of their assumptions, scope, and evidence. The standard saturated incidence is more ideal for uniform population-level behavioral responses, while the network-based formulation is preferable when connection and exposure structure predominate behavioral adaptations. This comparative framework helps make it clear when one model is right and also where further empirical reproducibility is needed.

- Emotional distress and public compliance: Public cooperation with health treatments is extensively shaped by emotional reactions during epidemics, including dread, worry, and depression. Growing empirical studies show an increase in psychological suffering during infectious outbreaks, disproportionately affecting those with low socioeconomic levels [611,612,613,614,615,616,617,618,619]. These emotional states might compromise public health policies, lead to avoidance behaviors, disseminate false information, or even result in panic-driven decision-making.Media coverage sometimes magnifies these dynamics by raising perceived threats, which could then enhance maladaptive behavior reactions. For instance, Taylor et al. discovered during Australia’s equine influenza epidemic that financial uncertainty was strongly correlated with emotional stress, therefore illustrating how structural vulnerabilities impact psychological effects [612]. Socioeconomic level also influences coping strategies like hope for recovery or faith in organizations. Studies by Zhou et al., Li et al., and Vázquez et al. validate that these emotional elements, especially optimism and trust, act as moderating variables that may either buffer psychological stress or magnify its impact under uncertainty [615,617,619].Carbonaro and Serra [121] presented a model reflecting the stochastic evolution of emotional states, including anxiety and reliability, over time-dependent interpersonal encounters, thereby capturing such dynamics quantitatively. The model characterizes the probability of a certain emotional state shared across persons i and j developing via the following equation:where and represent gain and loss terms influenced by both self-reflection and emotional contagion through social networks. This formulation corresponds with expansions of behavioral SIR models, in which emotional dynamics interact with epidemiological states to enable researchers to predict adaptive behavioral transitions such as risk denial, greater compliance, or panic-induced withdrawal. Including such emotion-specific processes into disease modeling algorithms helps one to better grasp how psychological elements affect epidemic paths, particularly in times of crisis that test public health infrastructure and collective emotional resilience.

- Behavioral adaptation and disease transmission: Essential to epidemic outcomes and influenced by psychological elements like anxiety, unpredictability, exhaustion, and compliance to social norms are behavioral reactions that include social distance, hand cleanliness, and restricted mobility [599,610,620,621,622,623,624,625,626,627,628,629,630,631,632,633,634,635,636,637,638,639,640,641,642,643,644,645,646,647,648,649,650,651,652,653]. Behavioral changes like panic purchasing, broad mask usage, remote working, and altered travel patterns were clearly seen during the COVID-19 epidemic. Though first successful, these adaptive activities often fade with time from habituation or tiredness [654,655,656,657,658,659,660,661,662,663,664,665,666,667,668,669]. Trust in authority and social conventions mediates these actions; tiredness may cause them to fade over time [670,671,672,673,674]. Using fractional derivatives [609], transitions between immune and non-immune susceptibles depending on past exposure [675], and time-dependent vaccination and distancing approaches [676], models including memory-driven alterations in vaccination attitudes describe behavioral adaptability. These strategies draw attention to how adaptive feedback shapes the course of an epidemic.

- Migration restrictions and their psychological effects: Recommended responses to epidemic challenges include migration controls like lockdowns, quarantines, and travel bans, but they also have major psychological effects. Public confidence and obedience may be undermined by fear, solitude, and financial stress linked with these regulations [227,677,678,679]. Several research studies show that a lack of accessibility and insufficient communication aggravate these consequences, hence lowering the effectiveness of mobility limitations. Mathematical models sometimes show such constraints as control variables controlling isolation or social distance. Researchers have worked on models, for example, that limit movement through the variables signaling remoteness and isolation rather than geographical restrictions [599,609,680,681]. These depictions help one understand how public perceptions and legislative stringency interact to affect results. Trust in authority and clear communication define public adherence most of all; contradictory communication reduces compliance [682,683,684,685].

- Advances in behaviorally informed modeling: Recent advances in epidemiological modeling have progressively recognized how closely disease dynamics are shaped by emotional contagion and behavioral feedback. Compartmental models are often lacking in reflecting these intricate psychological dynamics. Bedson et al. underline the shortcomings of traditional models by means of a thorough evaluation of approaches that include psychological aspects in epidemic models, therefore supporting more complex behavioral representations [686]. One important example of this kind of progress is the prevalence-elastic behavior model, which holds that people change their social distance or vaccine intake in response to imagined illness risks [687]. Building on this, Dutta et al. show how to simulate long-memory behavioral effects using fractional calculus, hence allowing the capturing of continuous individual responses throughout time [609]. In companion work, Dutta et al. and Saha et al. include immunological variability, optimum vaccination techniques, and dynamic feedback mechanisms, including adaptive social distance, therefore offering more realistic representations of behavioral development during epidemics [675,676].Coupled contagion models improve our knowledge substantially as they concurrently represent the transmission of transmissible diseases and anxiety. Studies by Funk et al. and Epstein et al. have demonstrated that these systems may produce intricate dynamics, including oscillating epidemic patterns [688,689]. Particularly, Agent_Zero, an agent-based model (ABM), shows a major advance in this respect. These models provide a detailed picture of behavioral variety by simulating diverse creatures whose decisions are shaped by cognitive, emotional, and social stimuli [690]. Further improving the relevance of these models is the growing availability of real-time behavioral data and qualitative insights from risk communication and community involvement (RCCE) approaches. Infection paths are much shaped by social and psychological elements, including individual vulnerability, patterns of social mixing, and public activity engagement. Emphasizing the part of behaviorally driven variation in epidemic dissemination, ABMs have revealed how psychosocial interactions dramatically affect asymptomatic transmission patterns in COVID-19 [691].Gigerenzer’s idea of psychological AI also brings heuristic-based methods that give human judgment under ambiguity top priority. His criticism of data-centric epidemic forecasting systems such as Google Flu Trends emphasizes the need for psychological heuristics, such as the recency effect, which, in some situations, can beat more intricate prediction algorithms [692]. These results highlight the need to include limited rationality and psychological realism into epidemic models to improve their predictive and explanatory capacity.

- Psychoneuroimmunological insights: A key assumption of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) is that psychological moods and immunological function have a complicated, bidirectional interaction. Depression, anxiety, and chronic stress are among the mental health disorders most linked to aggravation of inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), via the gut–brain axis and vagal tone changes [693,694,695]. Results from animal models also confirm this link; for example, experimentally induced psychological discomfort has been found to disturb gut flora and decrease immune function, therefore highlighting physiologically ingrained routes by which emotions affect immunological resistance [696,697].These revelations are now included in models of epidemiology. Dutta et al. use fractional-order models, for instance, to capture memory-dependent behavioral reactions like vaccination reluctance, therefore illustrating how cognitive biases and belief systems directly affect immunological risk via behavioral paths [609]. Models of HIV control show a similar junction of psychological and immunological processes whereby cognitive assessment of risk and informational awareness shape the intake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), therefore tying emotional states to population-level disease resistance [610]. Further extending this integration, Lv et al. suggest an enhanced SIRS framework including psychological variation among people. Under this approach, the population is split into level-headed and impatient groups to reflect differences in behavioral responsiveness during public crises [698]. Dynamic psychological interactions bridge ideas from personality psychology and conventional epidemiology to simulate emotional contagion, much as infectious disease transmission is modeled. This formulation offers a convincing structure for modeling panic spread and its influence on epidemic dynamics. These models, taken together, highlight the requirement of epidemiological methods that consider the interactions among psychological features, emotional reactions, and immunological results. Such integration improves the forecasting power of models under actual psychosocial settings and provides a more complete knowledge of population health.

6. Psychological Effects in Advanced Technology, AI, and Complex Systems

- (i)

- Facial attractiveness and visual psychology: Deep learning architectures like AlexNet and ResNet, trained on datasets like SCUT-FBP5500, have efficiently represented human impressions of face aesthetics molded by consistent psychological preferences across age, culture, and gender [725,726,727]. Combining local and global face characteristics with multi-task learning helps Vahdati et al. increase prediction accuracy [728]. Meta-learning techniques have been used to personalize elegance evaluation and dynamically adjust to user-specific aesthetic choices, hence addressing individual variance [729,730,731,732,733].

- (ii)

- Affective computing and emotion recognition: Originally put up by Picard, affective computing recognizes the importance of emotion in intelligent behavior from a viewpoint compatible with Simon’s claim that cognition is incomplete without affect [734,735]. Bechara et al. have shown that deficits in emotional-processing brain areas compromise decision-making even in cases with logical thinking intact [736]. Emotion identification systems depend more and more on multimodal data, including speech characteristics [737], facial action units (e.g., FACS) [738,739], and EEG signals [740,741]. Liu et al. suggested a spatio-temporal convolution attention neural network (3DCANN) leveraging dual attention processes to show better classification performance over many channels and time frames for EEG-based emotion identification [742]. In a similar vein, Cheng et al. presented MSDCGTNet, a new multi-scale CNN and gated transformer-based model that allows accurate and effective emotional state identification throughout several benchmark datasets [743]. Effective temporal emotional signals in speech-based systems are captured by deep learning models, including LSTM and the upgraded BLSTM-DSA architecture [744,745]. With depression diagnosis systems combining BP neural networks and Adaboost algorithms reaching over 81% accuracy, multimodal approaches integrating voice and facial expression have also demonstrated great efficacy in mental health diagnoses [746]. Hernández-Marcos and Ros suggested a self-learning emotional framework for AI agents based on reinforcement learning ideas, hence extending this trend [747]. Their approach shows congruence with natural emotional patterns and develops synthetic feelings by means of the temporal dynamics of reward-based variables.

- (iii)

- Music, emotion, and psychological regulation: An essentially emotional medium with great regulating power is music. AI-based music systems are now able to analyze and modify musical output in real time to reflect or impact a user’s emotive state are. Showing statistically substantial categorization accuracy of emotional states, Affective Brain-Computer Music Intervals (aBCMI) use EEG inputs to identify arousal and valence levels and change music accordingly [748,749]. Strong connections between auditory stimuli and emotional responses throughout cortical and limbic networks help EEG-based studies to support these systems [750]. Today, EEG-based functional connectivity during emotional experience has attracted significant attention. Moreover, as pointed out in [751] and references therein, EEG evidence consistently reveals shared neural mechanisms between affect and cognition, overlapping anatomical substrates, and coordinated temporal dynamics between emotional and cognitive processes. This underscores the need to develop unified mathematical models that preserve insights from specialized research while capturing the holistic nature of mental function. It is expected that such models will assist in areas ranging from clinical intervention to educational technology, and from brain–computer interfaces to artificial intelligence [751], with applications in developing new therapies for emotional rehabilitation programs, psychological trauma recovery, and other fields.

7. Psychological Effects in Finance, Business, Economics, and Other Areas of Social Sciences

- Cognitive and neural foundations of financial decisions: Frydman and Camerer examine how cognitive biases and brain processes influence financial behavior in a variety of areas, including household finance and business decision-making. They stress the role of overconfidence, overtrading, and insufficient financial literacy in driving unsatisfactory results. Neuroscientific research utilizing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) reinforces these behavioral trends by linking brain activity to risk perception and investment behavior [760].Frydman and Camerer [760], as well as Frydman et al. [761], use fMRI data to give empirical support for the “realization utility hypothesis”, which holds that investors derive utility at the moment of realizing profits or losses rather than from intertemporal wealth growth. This behavioral inclination can be represented as follows:where is the vector of realized returns over time, is the vector of corresponding purchase prices, and is a discount factor. The utility function u is determined not by total wealth but by the emotional enjoyment obtained from temporary gains or losses, particularly when selling assets.Taken together, these findings indicate that even at the most basic level of trading, emotional responses to realized gains and losses can systematically shape financial behavior.Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory provides a psychologically based alternative to anticipated utility theory by elucidating how humans really assess risk and uncertainty. The conventional model posits a linear utility function with rational agents maximizing predicted utility. In contrast, prospect theory provides a value function defined by gains and losses relative to a reference point, rather than eventual wealth levels [762]. This function is concave for gains and convex for losses, which means that it becomes less sensitive as the amount of money lost increases. It is also steeper for losses than for gains, which is in line with the idea of loss aversion, which says that losses are more important than gains of the same size. Mathematically, this is represented by a value function , which allocates a subjective value to each outcome x. In this case, x stands for the change in wealth compared to a reference point. Gains are positive and losses are negative. The function is defined as follows:where represents the degree of loss aversion, and captures diminishing sensitivity to gains and losses [763]. Empirical estimates often indicate , signifying that losses are often valued more than twice as much as corresponding benefits.Prospect theory includes a probability weighting function in addition to the value function. This function reflects the fact that people tend to put too much weight on tiny probabilities and not enough weight on moderate to high probabilities. This conduct diverges from the utilization of objective probability in anticipated utility theory. The Prelec weighting function that is most often used is as follows:where shows how the distortion works. When , the function becomes the identity line , which means that the perception is not skewed. For , it has the S-shape that is typical of it, with low probabilities getting too much weight and high probabilities getting too little weight. Both the value function and the probability weighting function are the two main parts of prospect theory. They explain a lot of strange things that happen when people make decisions under risk, like the certainty effect, the isolation effect, and preference reversals. This makes prospect theory very important in behavioral finance and economics.Frydman et al. provide additional evidence for the realized utility theory by demonstrating that brain responses, particularly in reward-related regions, correspond to the pleasure obtained from selling winning assets [761]. Recent emotional neuroscience research shows that brain signals from areas like the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) can predict market-level outcomes such as crowdfunding campaign success and collective investing decisions. These findings highlight how emotional and cognitive processes accessible by brain imaging help to better understand financial psychology and behavior [114].Having established these micro-level cognitive and neural mechanisms, we can now examine how similar psychological forces scale up to shape aggregate market behavior and asset prices.

- Market behavior, investor biases, and overconfidence: Shiller questions the efficient market theory, demonstrating that stock values are too volatile due to investor mood, over-reaction, and herd behavior [764,765]. He considers market prices to deviate from fundamentals owing to investor mood. A basic mispricing dynamic, using sentiment , may be represented as follows:where P signifies the observed price, F is the fundamental value, and weights the psychological sentiment. On the contrary, Odean and Barber show empirical proof of the overconfidence bias and disposition impact, proving that these kinds of actions lower portfolio returns [766,767]. Barber and Odean highlight even more personal investor prejudices, including overconfidence-driven excessive trading and the inclination to sell successes while keeping losses [768]. Greenwood and Shleifer study extrapolative expectations, in which investors wildly extrapolate historical returns into the future, hence creating asset bubbles [769].Beyond these market-wide anomalies, psychological limitations also manifest in how individuals construct portfolios and process basic financial information.

- Cognitive foundations and decision-making: Lusardi and Mitchell investigate the effects of inadequate financial literacy, stressing bad saving habits and credit mismanagement, often exacerbated by restricted attention and difficulties in grasping fundamental financial ideas such as compound interest [770]. Hedesström et al. and Benartzi and Thaler show that rather than addressing the mean-variance portfolio optimization issue, investors often depend on heuristics, including the naïve rule:where n is the number of available assets, is the vector of portfolio weights, is the vector of expected returns, is the covariance matrix of returns, and denotes the investor’s risk aversion. Heuristic-based decision-making of this kind sometimes results in ineffective diversification [771,772].Unlike the efficient market hypothesis, which Shiller challenges with data of too much stock price volatility resulting from investor mood and herd behavior [764,765], other research implies that market efficiency may still be maintained. For example, Akdeniz et al. and Lewis and Whiteman find that under strong decision-making models and general equilibrium theories, efficiency could show up [773,774].While these analyses focus on cross-sectional portfolio choice and market efficiency, psychological influences are equally pronounced in how people trade off consumption and saving over time.

- Financial literacy and temporal choice behavior: Detrimental financial conduct is mostly determined by low financial literacy. Lusardi and Mitchell demonstrate how poor knowledge of ideas like compound interest results in insufficient savings and credit misbehavior [770]. Benartzi and Thaler investigate the heuristic [772], in which investors forgo sophisticated research by simply diversifying blindly across choices. Hyperbolic discounting better captures time-inconsistent desires:where U is the total utility, is the instantaneous utility from consumption at time t, and reflects the degree of present bias. Berns et al. relate these kinds of behaviors to brain processes underpinning intertemporal decision, therefore relating impulsive expenditure to hyperbolic discounting [775]. Hershfield et al. show that seeing one’s future self lowers current bias and promotes saving [776]. Thaler’s theory of mental accounting helps one to understand how individuals divide their money, usually irrationally, which results in contradictory decisions in different situations [777].Beyond cognitive limits and present-biased preferences, affective states and lived experiences further color how individuals perceive and manage financial risks.

- Emotional and experiential influences: Financial decision-making is much shaped by emotions and prior experiences, therefore questioning presumptions of logical conduct. Kuhnen and Knutson emphasize the neurological underpinnings of economic decisions by demonstrating how directly emotional emotions mediated by neurotransmitters such as dopamine impact risk preferences [778]. Cameron and Shah also discover that stressful events, including natural disasters, can cause ongoing changes in risk-taking behavior [779]. Following trauma, they model ongoing risk-aversion changes. One may write a dynamic utility formulation including emotional state as follows:where captures traumatic or emotionally salient events, and is the decay rate of emotional impact. This highlights emotion–memory coupling in behavioral responses. Personal financial history is also very important. Malmendier and Nagel show that those who experienced significant inflation during formative years often choose more cautious investing approaches [780]. Hoelzl and Huber highlight the limits of experience foresight in financial planning, as borrowers can understate long-term repayment obligations, which results in over-indebtedness [781]. Beyond financial situations, subjective emotional states have great predictive power. Simple self-reported emotions, according to Kaiser and Oswald, can predict behavior like job changes and hospital visits better than conventional economic indicators [782]. Under uncertainty and adaptive dynamics specifically, these results highlight the need to include emotional and sensory aspects in models of economic and social behavior. Roberts et al.’s affect-informed decision paradigm also provides insightful analysis for economic psychology, as it shows that emotional valence may change perceived value under various contextual weightings, thereby changing economic choice behavior [151].These findings naturally connect to broader economic–psychological frameworks that formalize how subjective states mediate between objective environments and observable economic behavior.

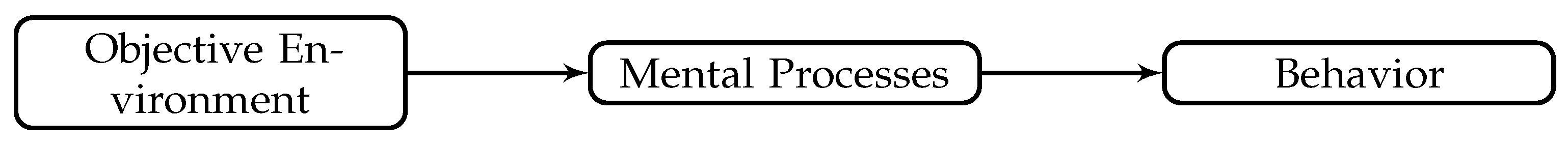

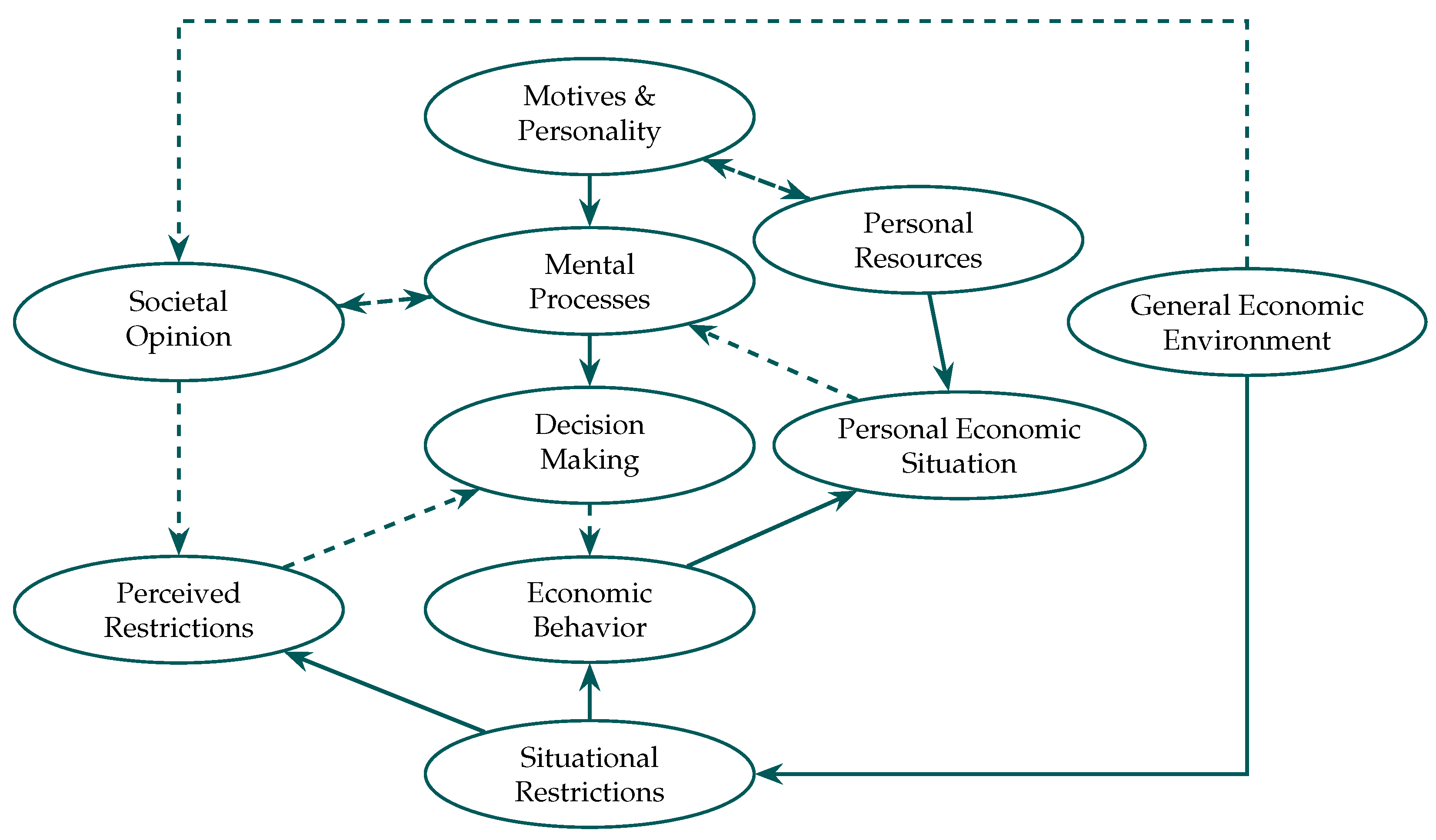

- Economic psychology and mental models: Economic psychology focuses on the connection between mental processes and economic behavior. Examining how motivation, perspective, decision-making, and social factors impact financial decisions, Antonides offers an integrated picture of psychology and economics [783]. Based on psychological motives and resources, the book explores the Values and Lifestyles (VALS) model, which puts readers into categories including Survivors, Achievers, and Emulators. Structured as a causal chain, Figure 2 offers a fundamental economic psychology model: the external environment (e.g., money; employment) impacts mental processes (e.g., attitudes; expectations), which in turn define behavior (e.g., spending; saving). Rooted in behaviorist psychology, this S-O-R (Stimulus–Organism–Response) model shows how subjective interpretation moderates the effect of economic stimuli [784,785,786].By separating objective economic elements from subjective psychological processes, Figure 3 broadens this model and shows how mental representations, emotions, and societal standards shape financial conduct. This framework shows how closely economic conduct is ingrained in a larger framework of social influence, perspective, and motivation [783].At the level of strategic interaction, these psychological foundations become especially salient when individual incentives conflict with collective welfare.

- Strategic behavior and collective outcomes: The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a prime example of how individual rationality could produce collectively less than ideal results in economic settings. Using this approach, Antonides emphasizes the need for trust, justice, and social conventions in allowing collaboration and enhancing results beyond what simple self-interest suggests for financial decisions [783].Relatedly, when economic behavior is embedded in institutions such as taxation and public spending, psychological responses to fairness and norms can strongly influence contributions to public goods.

- Crowding-out effect and public goods: Economic psychology, to a great extent, investigates how psychological incentives influence public policy responses. It clarifies voluntary contribution decreases under taxes by means of the following equation:where signifies the individual contribution, is intrinsic motivation, denotes the perceived fairness loss due to taxation, and represents the effect of social norms. The crowding-out effect explains how higher government expenditure could lower public good voluntary donations. Apart from substitution effects, this phenomenon is driven by perceived justice, societal conventions, and personal beliefs that defy the conventional wisdom of only maximizing behavior [783].Psychological determinants of economic behavior are equally crucial when individuals and societies confront risks that are complex, low-probability, or difficult to interpret.

- Risk perception and societal decision-making: Slovic and associates investigate how people discern danger, depending more on emotions and heuristics than on probability [787,788,789,790,791,792,793]. These impressions help to form reactions to public hazards, financial risks, and legal rules. Slovic contends, in reality, that emotional heuristics define risk, and the expected value becomes [789]:where is the affective response associated with the outcome x, often diverging from statistical risk assessments. Garling et al. contend that financial crises are caused in part by psychological elements like capital delusion, framing effects, and crowd behavior. They support better financial education that seeks to reduce such prejudices [794].These insights have direct consequences for how markets are regulated and how policies are designed to protect consumers and maintain stability.

- Policy implications and regulation: Campbell et al. investigate how present and status quo bias among behavioral biases affect consumer saving and investment, therefore implying the requirement of customized treatments [795]. According to Akerlof and Shiller, sometimes systemic crises result from emotions, tales, and group dynamics over-riding logical conduct in financial markets [796]. Models of debt and savings guided by behavior combine limited rationality and status quo bias. For example, Bertrand et al. demonstrate that psychological frictions like complexity and framing affect consumer choices on credit intake in addition to interest rates [797]. These results draw attention to cognitive overload and status quo bias, which may be abstracted as a threshold-based behavioral paradigm whereby changes only occur if perceived value increases surpass a psychological cost. Mathematically, it can be modeled as follows:where is a threshold for inertia reflecting emotional or cognitive conflict, and status quo bias suggests that change is avoided until advantages exceed . Also, denotes the net utility gain from switching from the current (status quo) to a new state, and signifies the decision to accept or reject a credit offer. Bertrand et al. look at cognitive overload and framing in debt decisions; Lewis addresses psychological aspects of tax compliance [798]. Selective attention biases shown by Sicherman et al. help to explain overtrading and inadequate asset allocation [799].Debates over market volatility and efficiency further illustrate how far psychological considerations have reshaped the interpretation of financial dynamics.

- Alternative views on market volatility: Shill stresses elevated volatility in stock prices [764]; however, Akdeniz et al. and Lewis & Whiteman provide counterpoints demonstrating that markets may stay efficient or even under-respond to information when modeled under general equilibrium or strong decision frameworks [773,774]. This review shows the need for including psychological insights into financial and economic models. Behavioral finance offers a more realistic framework for analyzing policy design, market behavior, and decision-making by including cognitive limits, emotions, and biases.At the broadest level, these strands of research converge in explaining how psychological forces contribute to financial instability and large-scale economic crises.

- Broader implications and financial crises: Cognitive biases, including overconfidence, framing effects, and herd behavior, help to explain financial instability and crises, according to Garling et al. and Akerlof and Shiller [794,796]. Lewis and Bertrand et al. stress how behavioral biases also influence tax compliance and debt behavior [797,798]. Slovic’s research on risk perception emphasizes how different people misinterpret financial dangers depending on emotions and heuristics, therefore deviating from professional opinions [788,789,791].

8. Decision-Making with Psychological Effects

8.1. Visual Cognition and Cognitive Biases

8.2. Emotion, Sleep Deprivation, and Risk-Taking

8.3. Stochastic Dynamics Under Uncertainty

8.4. Psychological Feedback in AI Systems

8.5. Dynamic Decision Systems and Trait Modulation

8.6. Collective Decision-Making and Emergent Responsiveness

8.7. Applications to Biosocial and Ecological Systems

9. Nonequilibrium Phenomena, Nonlocality, and Complex Psychological Behavior

- t: time;

- : real-valued state variable representing the emotional intensity (e.g., affection or rejection);

- : probability density function (PDF) of individual A’s emotional state x at time t;

- : time-dependent inner evolution rate (velocity) of the emotional state x for individual A;

- : transport term capturing propagation of internal changes in emotional space;

- : external interaction term (gain-loss type) that models the stochastic effect of interactions between individuals A and B, which includes probabilistic changes in feelings due to actual encounters or communication, and depends on both individuals’ emotional state distributions and .

10. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Zaatari, W.; Maalouf, I. How the Bronfenbrenner bio-ecological system theory explains the development of students’ sense of belonging to school? SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221134089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, W.B. The James-Lange theory of emotions: A critical examination and an alternative theory. Am. J. Psychol. 1927, 39, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S.; Singer, J. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 69, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, K.R.; Moors, A. The Emotion Process: Event Appraisal and Component Differentiation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, C.M.; Ram, N.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.M. Integrating dynamic and developmental time scales: Emotion-specific autonomic coordination predicts baseline functioning over time. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2022, 171, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretter, F.; Löffler-Stastka, H. The human ecological perspective and biopsychosocial medicine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M. Linking biodiversity and ecosystems: Towards a unifying ecological theory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B.; Melnik, R. Self-Organised Critical Dynamics as a Key to Fundamental Features of Complexity in Physical, Biological, and Social Networks. Dynamics 2021, 1, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B.; Dankulov, M.M.; Melnik, R. Evolving cycles and self-organised criticality in social dynamics. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 171, 113459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, W.M. Biomathematics: Being the Principles of Mathematics for Students of Biological Science; C. Griffin & Company, Limited: Lichfield, UK, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Rashevsky, N. Mathematical Biophysics and Psychology. Psychometrika 1936, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashevsky, N. Mathematical Biophysics; Dover Publictions: Garden City, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Bull. Math. Biol. 1990, 52, 153–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology I: An Introduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein-Keshet, L. Mathematical Models in Biology; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin, C.J.; Axelrod, J.D. Biology by numbers: Mathematical modelling in developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelbach, G.G.; McGill, B.J. Chapter The Fundamentals of Predator–Prey Interactions. In Community Ecology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermeer, J. How populations grow: The exponential and logistic equations. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2010, 3, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccino, N.; Price, P.W. Population Dynamics: New Approaches and Synthesis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.; Melnik, R. Nonlocal models in biology and life sciences: Sources, developments, and applications. Phys. Life Rev. 2025, 53, 24–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuaje, F. Computational discrete models of tissue growth and regeneration. Brief. Bioinform. 2011, 12, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, T. Topological properties of periodic and chaotic attractors. In Novel Research Aspects in Mathematical and Computer Science; Wang, X., Ed.; B P International: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 7, pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Coppin, G.; Sander, D. Theoretical approaches to emotion and its measurement. In Emotion Measurement, 7th ed.; Meiselman, H.L., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, C.J.; Reijneveld, J.C. Graph theoretical analysis of complex networks in the brain. Nonlinear Biomed. Phys. 2007, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: Graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O.; Tononi, G.; Kötter, R. The human connectome: A structural description of the human brain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2005, 1, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, D.; Lambiotte, R.; Bullmore, E.T. Modular and hierarchically modular organization of brain networks. Front. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, S.; Salvador, R.; Whitcher, B.; Suckling, J.; Bullmore, E. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, S.F.; Bridgeford, E.W.; Bassett, D.S. Small-World Propensity and Weighted Brain Networks. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, S.B.; Sejnowski, T.J. Communication in neuronal networks. Science 2003, 301, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherniak, C. Component placement optimization in the brain. J. Neurosci. 1994, 14, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klyachko, V.A.; Stevens, C.F. Connectivity optimization and the positioning of cortical areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7937–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovskii, D.B.; Schikorski, T.; Stevens, C.F. Wiring optimization in cortical circuits. Neuron 2002, 34, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniak, C.; Mokhtarzada, Z.; Rodriguez-Esteban, R.; Changizi, K. Global optimization of cerebral cortex layout. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.G.; Southgate, E.; Thomson, J.N.; Brenner, S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 1986, 314, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, J.E.; Laughlin, S.B. Energy limitation as a selective pressure on the evolution of sensory systems. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 211, 1792–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovskii, D.B. Exact Solution for the Optimal Neuronal Layout Problem. Neural Comput. 2004, 16, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.; Suckling, J.; Coleman, M.R.; Pickard, J.D.; Menon, D.; Bullmore, E. Neurophysiological Architecture of Functional Magnetic Resonance Images of Human Brain. Cereb. Cortex 2005, 15, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.; Hilgetag, C.C. Spatial growth of real-world networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 036103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.; Hilgetag, C.C. Modelling the development of cortical networks. Neurocomputing 2004, 58, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, S.H.; Jeong, H.; Barabási, A.L. Modeling the Internet’s large-scale topology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13382–13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vértes, P.E.; Alexander-Bloch, A.F.; Gogtay, N.; Giedd, J.N.; Rapoport, J.L.; Bullmore, E.T. Simple models of human brain functional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5868–5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, Y.; Nagatani, T. Scaling behavior of crowd flow outside a hall. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2001, 292, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Isobe, M.; Nagatani, T.; Takimoto, K. Lattice gas simulation of experimentally studied evacuation dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 067101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Farkas, I.; Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 2000, 407, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, A.; Steffen, B.; Lippert, T. Basics of modelling the pedestrian flow. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2006, 368, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticco, I.M.; Frank, G.A.; Cornes, F.E.; Dorso, C.O. A re-examination of the role of friction in the original Social Force Model. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, D.R.; Dorso, C.O. Microscopic dynamics of pedestrian evacuation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2005, 354, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, D.R.; Dorso, C.O. Morphological and dynamical aspects of the room evacuation process. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2007, 385, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Kashimori, Y.; Kambara, T. A model describing collective behaviors of pedestrians with various personalities in danger situations. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 2002, ICONIP’02, Singapore, 18–22 November 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 2083–2087. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Huang, H.J. A mobile lattice gas model for simulating pedestrian evacuation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2008, 387, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.H.; Ni, S. Simulation of evacuation processes using a multi-grid model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2006, 363, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L. A continuum theory for the flow of pedestrians. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2002, 36, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, R.M.; Rosini, M.D. Pedestrian flows and non-classical shocks. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2005, 28, 1553–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, R.L.; Janssen, M.A. Computational models of collective behavior. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.M.; Huang, H.C.; Wang, P.; Yuen, K. A game theory based exit selection model for evacuation. Fire Saf. J. 2006, 41, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoliang, Z.; Lizhong, Y.; Jian, L. Exit dynamics of occupant evacuation in an emergency. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2006, 363, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, L.; Lizhong, Y.; Daoliang, Z. Simulation of bi-direction pedestrian movement in corridor. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2005, 354, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.J.; Tapang, G.; Lim, M.; Saloma, C. Streaming, disruptive interference and power-law behavior in the exit dynamics of confined pedestrians. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2002, 312, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas, A.; Cornejo, M.; Mainemer, D.; Toledo, B.; Rogan, J.; Munoz, V.; Valdivia, J. Cellular automaton model for evacuation process with obstacles. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2007, 382, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Song, W. Cellular automaton simulation of pedestrian counter flow considering the surrounding environment. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 046112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamagami, T.; Hirata, H. Method of crowd simulation by using multiagent on cellular automata. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC International Conference on Intelligent Agent Technology (IAT 2003), Halifax, NA, Canada, 13–17 October 2003; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, A.; Nishinari, K.; Schadschneider, A. Friction effects and clogging in a cellular automaton model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 056122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Niu, H. Simulation of Bi-direction Pedestrian Movement in Corridor Based on Crowd Space. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 138, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Chen, T.; Yuan, H.; Fan, W. Cellular automaton simulation of pedestrian counter flow with different walk velocities. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 74, 036102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Park, J. Discrete element method for emergency flow of pedestrian in S-type corridor. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 7469–7476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Park, J. Main factor causing “faster-is-slower” phenomenon during evacuation: Rodent experiment and simulation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Yang, Y. Development of evacuation model for human safety in maritime casualty. Ocean Eng. 2004, 31, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, H.; Harada, E.; Kubo, Y.; Sakai, T. Particle-system model of the behavior of crowd in tsunami flood refuge. Annu. J. Coast. Eng. JSCE 2004, 51, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Abustan, M.S.; Harada, E.; Gotoh, H. Numerical simulation for evacuation process against tsunami disaster at Teluk Batik in Malaysia by multi-agent DEM model. In Proceedings of the Coastal Engineering, JSCE, Nagoya, Japan, 5–7 September 2012; Volume 3, pp. 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, Y. Numerical Simulation of Pedestrian Flow at High Densities. Pedestr. Evacuation Dyn. 2003, 3, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Langston, P.A.; Masling, R.; Asmar, B.N. Crowd dynamics discrete element multi-circle model. Saf. Sci. 2006, 44, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, H.; Harada, E.; Andoh, E. Simulation of pedestrian contra-flow by multi-agent DEM model with self-evasive action model. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhong, T.; Liu, M. Modeling crowd evacuation of a building based on seven methodological approaches. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudenberg, D.; Newey, W.; Strack, P.; Strzalecki, T. Testing the drift-diffusion model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 33141–33148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellmer, S.; Lindner, B. Decision-time statistics of nonlinear diffusion models: Characterizing long sequences of subsequent trials. J. Math. Psychol. 2020, 99, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.L. The Poisson shot noise model of visual short-term memory and choice response time: Normalized coding by neural population size. J. Math. Psychol. 2015, 66, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodiev, P.; Tessone, C.J.; Schweitzer, F. Quantifying the effects of social influence. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodiev, P.; Schweitzer, F. The ambigous role of social influence on the wisdom of crowds: An analytic approach. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 567, 125624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghani, M.; Sarvi, M. Imitative (herd) behaviour in direction decision-making hinders efficiency of crowd evacuation processes. Saf. Sci. 2019, 114, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.I.; Shadlen, M.N. The neural basis of decision making. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 30, 535–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogacz, R.; Brown, E.; Moehlis, J.; Holmes, P.; Cohen, J.D. The physics of optimal decision making: A formal analysis of models of performance in two-alternative forced-choice tasks. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitzer, S.; Park, H.; Blankenburg, F.; Kiebel, S.J. Perceptual decision making: Drift-diffusion model is equivalent to a Bayesian model. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, P.R.; Park, H.; Warkentin, A.; Kiebel, S.J.; Bitzer, S. A Bayesian reformulation of the extended drift-diffusion model in perceptual decision making. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, A.; Colonius, H. A two-stage diffusion modeling approach to the compelled-response task. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 128, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Varol, O.; Varamesh, A.; Barron, A.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Scheffer, M.; Bollen, J. The minute-scale dynamics of online emotions reveal the effects of affect labeling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokka, K.; Park, H.; Jansen, M.; DeAngelis, G.C.; Angelaki, D.E. Causal inference accounts for heading perception in the presence of object motion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9060–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokka, K.; DeAngelis, G.C.; Angelaki, D.E. Multisensory integration of visual and vestibular signals improves heading discrimination in the presence of a moving object. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 13599–13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, J.P.; Angelaki, D.E. Cognitive, systems, and computational neurosciences of the self in motion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Ma, L.; Polina, D. Revealing brain’s cognitive process deeply: A study of the consistent EEG patterns of audio-visual perceptual holistic. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1377233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieu, T.; Melnik, R. Social human collective decision-making and its applications with brain network models. In Crowd Dynamics, Volume 4: Analytics and Human Factors in Crowd Modeling; Bellomo, N., Gibelli, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 103–141. [Google Scholar]

- Thieu, T.; Melnik, R. Modelling the behavior of human crowds as coupled active-passive dynamics of interacting particle systems. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 2025, 27, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, J.; Bonnen, K. Continuous psychophysics: Past, present, future. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2025, 29, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waskom, M.L.; Okazawa, G.; Kiani, R. Designing and Interpreting Psychophysical Investigations of Cognition. Neuron 2019, 104, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Georgiou, P.G. Behavioral Signal Processing: Deriving Human Behavioral Informatics From Speech and Language. Proc. IEEE 2013, 101, 1203–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Gutiérrez, D.; Sorrel, M.A.; Shanks, D.R.; Vadillo, M.A. The Conscious Side of ‘Subliminal’ Linguistic Priming: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Reliability Analysis of Visibility Measures. J. Cogn. 2025, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Oever, S.; Titone, L.; Te Rietmolen, N.; Martin, A.E. Phase-dependent word perception emerges from region-specific sensitivity to the statistics of language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320489121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, B. Beyond the brain: Towards a mathematical modeling of emotions. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling in Physical Sciences (IC-MSQUARE 2021), Virtual, 6–9 September 2021; Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 2090, p. 012119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattek, A.M.; Wolford, G.L.; Whalen, P.J. A Mathematical Model Captures the Structure of Subjective Affect. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 508–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, N.; Kobyzev, I.; Hoey, J.; Poupart, P.; Sheikh, M.B. Generating Emotionally Aligned Responses in Dialogues using Affect Control Theory. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Vitale, J.; Williams, M.A. EEGS: A transparent model of emotions. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.02573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.E.; Hilpert, B.; Broekens, J.; Jokinen, J.P.P. Simulating Emotions with an Integrated Computational Model of Appraisal and Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa, H. Free-Energy Model of Emotion Potential: Modeling Arousal Potential as Information Content Induced by Complexity and Novelty. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 698252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Wu, X.; Ueda, K.; Kato, T. Free energy model of emotional valence in dual-process perceptions. Neural Netw. 2023, 157, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Dang, T.; Sethu, V.; Ambikairajah, E. Dual-Constrained Dynamical Neural ODEs for Ambiguity-aware Continuous Emotion Prediction. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; pp. 3185–3189. [Google Scholar]

- Kervadec, C.; Vielzeuf, V.; Pateux, S.; Lechervy, A.; Jurie, F. CAKE: Compact and accurate K-dimensional representation of emotion. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Li, N.; Fan, L.; Wei, J.; Xu, J. Integrative interaction of emotional speech in audio-visual modality. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 797277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Huangfu, X.; Tong, D.; He, A. Regional gray matter volume mediates the relationship between neuroticism and depressed emotion. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 993694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G. On the encoding of natural music in computational models and human brains. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 928841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Mock, J.; Irani, F.; Huang, Y.; Najafirad, P.; Golob, E. Multimodal explainable AI predicts upcoming speech behavior in adults who stutter. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 912798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Min, C.; Wang, C.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X. Electroencephalograph-based emotion recognition using brain connectivity feature and domain adaptive residual convolution model. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 878146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomala, J.; Kauttonen, J. Human’s Intuitive Mental Models as a Source of Realistic Artificial Intelligence and Engineering. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuroscience News. Detecting Hidden Brain States with Mathematical Models. Available online: https://neurosciencenews.com/math-models-brain-state-22789/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Silverstein, S.M.; Wibral, M.; Phillips, W.A. Implications of information theory for computational modeling of schizophrenia. Comput. Psychiatry 2017, 1, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Tan, Z.; Hou, H.; Li, G.; Cheng, A.; Qiu, Y.; Weng, K.; Chen, C.; Sun, P. Theoretical foundations of studying criticality in the brain. Netw. Neurosci. 2022, 6, 1148–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankulov, M.M.; Melnik, R.; Tadić, B. The dynamics of meaningful social interactions and the emergence of collective knowledge. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadić, B.; Dankulov, M.M.; Melnik, R. Mechanisms of self-organized criticality in social processes of knowledge creation. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 032307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadić, B.; Melnik, R. Fundamental interactions in self-organised critical dynamics on higher order networks. Eur. Phys. J. B 2024, 97, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, B.; Serra, N. Towards Mathematical Models in Psychology: A Stochastic Description of Human Feelings. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. 2002, 12, 1453–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, C. Post-traumatic stress disorder: Evolutionary perspectives. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, F.E. The Effects of Stigma on the Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction of Persons with Mental Illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1998, 39, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.C.; Salkovskis, P.M.; Warwick, H.M. An experimental investigation of the impact of biological versus psychological explanations of the cause of “mental illness”. J. Ment. Health 2005, 14, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.M.; Deb, P. The Effect of Chronic Illness on the Psychological Health of Family Members. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2003, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D.; Bybee, D.; Mowbray, C. Influences of maternal mental illness on psychological outcomes for adolescent children. J. Adolesc. 2002, 25, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.; Frech, A.; Carlson, D.L. Marital Status and Mental Health. In A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems; Williams, K., Frech, A., Carlson, D.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 306–320. [Google Scholar]

- Gilsbach, S.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Konrad, K. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with and without mental disorders. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iasevoli, F.; Fornaro, M.; D’Urso, G.; Galletta, D.; Casella, C.; Paternoster, M.; Buccelli, C.; de Bartolomeis, A. the COVID-19 in Psychiatry Study Group. Psychological distress in patients with serious mental illness during the COVID-19 outbreak and one-month mass quarantine in Italy. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobban, F.; Barrowclough, C.; Jones, S. A review of the role of illness models in severe mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrowclough, C.; Tarrier, N.; Johnston, M. Distress, Expressed Emotion, and Attributions in Relatives of Schizophrenia Patients. Schizophr. Bull. 1996, 22, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichsen, G.; Lieberman, J. Family attributions and coping in the prediction of emotional adjustment in family members of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 100, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, P.; Birchwood, M. The Omnipotence of Voices: A Cognitive Approach to Auditory Hallucinations. Br. J. Psychiatry 1994, 164, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchwood, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Chadwick, P.; Trower, P. Cognitive approach to depression and suicidal thinking in psychosis: I. Ontogeny of post-psychotic depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, P.; Sambrooke, S.; Rasch, S.; Davies, E. Challenging the omnipotence of voices: Group cognitive behavior therapy for voices. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrowclough, C.; Lobban, F.; Hatton, C.; Quinn, J. An investigation of models of illness in carers of schizophrenia patients using the Illness Perception Questionnaire. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 40, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, M.; Kjellin, L. Stigma by association: Psychological factors in relatives of people with mental illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchwood, M.; Mason, R.; MacMillan, F.; Healy, J. Depression, demoralization and control over psychotic illness: A comparison of depressed and non-depressed patients with a chronic psychosis. Psychol. Med. 1993, 23, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, A.P. A cognitive analysis of the maintenance of auditory hallucinations: Are voices to schizophrenia what bodily sensations are to panic? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1998, 26, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, O.F. Mass media images of mental illness: A review of the literature. J. Community Psychol. 1992, 20, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, O.F.; Roth, R. Television images of mental illness: Results of a metropolitan Washington media watch. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1982, 26, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, G. Impact of the film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, on attitudes towards mental illness. Psychol. Rep. 1983, 53, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, O.F.; Lefkowits, J.Y. Impact of a Television Film on Attitudes Toward Mental Illness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1989, 17, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannes, A.; Bui, E.; Arnaud, C.; Raynaud, J.P.; Revet, A. Preventive interventions in offspring of parents with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2321–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, J.; Clarke, G.N.; Weersing, V.R.; Beardslee, W.R.; Brent, D.A.; Gladstone, T.R.; DeBar, L.L.; Lynch, F.L.; D’Angelo, E.; Hollon, S.D.; et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 301, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardslee, W.R.; Brent, D.A.; Weersing, V.R.; Clarke, G.N.; Porta, G.; Hollon, S.D.; Gladstone, T.R.; Gallop, R.; Lynch, F.L.; Iyengar, S.; et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: Longer-term effects. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, G.S.; Tein, J.Y.; Riddle, M.A. Preventing the Onset of Anxiety Disorders in Offspring of Anxious Parents: A Six-Year Follow-up. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, W.K.; Fals-Stewart, W.; Kelley, M.L. Effects of parent skills training with behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism on children: A randomized clinical pilot trial. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanger, C.; Ryan, S.R.; Fu, H.; Budney, A.J. Parent training plus contingency management for substance abusing families: A complier average causal effects (CACE) analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 118, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A.; Netsi, E.; Lawrence, P.J.; Granger, C.; Kempton, C.; Craske, M.G.; Nickless, A.; Mollison, J.; Stewart, D.A.; Rapa, E.; et al. Mitigating the impact of persistent postnatal depression on child outcomes: A randomised controlled trial of an intervention to treat depression and improve parenting. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.D.; HajiHosseini, A.; Hutcherson, C.A. How bad becomes good: A neurocomputational model of affect-informed choice. Emotion 2024, 24, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S.; Cai, Q.; Omari, D.; Sanghvi, D.E.; Lyu, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Emotion regulation and mental health across cultures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 1176–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.L. Dialectical behavior therapy: Current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry 2006, 3, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff, L.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical behavior therapy in a nutshell. Calif. Psychol. 2001, 34, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Westerhof, G. The Model for Sustainable Mental Health: Future Directions for Integrating Positive Psychology Into Mental Health Care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G.; Callaway, C.A.; Zieve, G.G.; Gumport, N.B.; Armstrong, C.C. Applying the Science of Habit Formation to Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments for Mental Illness. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, Q.J.; Maia, T.V.; Frank, M.J. Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Särkkä, S. Bayesian Filtering and Smoothing; Institute of Mathematical Statistics Textbooks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, P.; Schirner, M.; McIntosh, A.R.; Jirsa, V.K. The Virtual Brain Integrates Computational Modeling and Multimodal Neuroimaging. Brain Connect. 2013, 3, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, L.F.; Vissers, N.; Wichers, M.; Geschwind, N.; Kuppens, P.; Peeters, F.; Borsboom, D.; Tuerlinckx, F. A Network Approach to Psychopathology: New Insights into Clinical Longitudinal Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. Emotion and decision-making explained: A précis. Cortex 2014, 59, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montague, P.R.; Dolan, R.J.; Friston, K.J.; Dayan, P. Computational psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, J.; Hallak, J.; Dursun, S.M.; Baker, G. Ayahuasca: Psychological and Physiologic Effects, Pharmacology and Potential Uses in Addiction and Mental Illness. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, C.S.; McKenna, D.J.; Callaway, J.C.; Brito, G.S.; Neves, E.S.; Oberlaender, G.; Saide, O.L.; Labigalini, E.; Tacla, C.; Miranda, C.T.; et al. Human psychopharmacology of hoasca, a plant hallucinogen used in ritual context in Brazil. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1996, 184, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Elices, M.; Franquesa, A.; Barker, S.; Friedlander, P.; Feilding, A.; Pascual, J.C.; Riba, J. Exploring the therapeutic potential of Ayahuasca: Acute intake increases mindfulness-related capacities. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.C.R.; Strassman, R.J.; Da Silveira, D.X.; Areco, K.; Hoy, R.; Pommy, J.; Thoma, R.; Bogenschutz, M. Psychological and neuropsychological assessment of regular hoasca users. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 71, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouso, J.C.; González, D.; Fondevila, S.; Cutchet, M.; Fernández, X.; Ribeiro Barbosa, P.C.; Alcázar-Córcoles, M.Á.; Araújo, W.S.; Barbanoj, M.J.; Fábregas, J.M.; et al. Personality, psychopathology, life attitudes and neuropsychological performance among ritual users of Ayahuasca: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Keyes, C.L. Mental Illness and Mental Health: The Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2010, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.; Eisenberg, D.; Perry, G.S.; Dube, S.R.; Kroenke, K.; Dhingra, S.S. The Relationship of Level of Positive Mental Health with Current Mental Disorders in Predicting Suicidal Behavior and Academic Impairment in College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2012, 60, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, M.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Cognitive psychology-based artificial intelligence review. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1024316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, M.A.; de Regt, E.B.; Andries, F.; van Agt, H.M.; Bijl, R.V.; de Boer, J.B.; Foets, M.; Hoeymans, N.; Jacobs, A.E.; Kempen, G.I.; et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daré, L.O.; Bruand, P.E.; Gérard, D.; Marin, B.; Lameyre, V.; Boumédiène, F.; Preux, P.M. Co-morbidities of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases in developing and emerging countries: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, G.; Catalano, A.; Bellone, F.; Russo, G.T.; Vicario, C.M.; Lasco, A.; Quattropani, M.C.; Morabito, N. As time goes by: Anxiety negatively affects the perceived quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, V.; Tomai, M.; Lauriola, M.; Martino, G.; Di, T.M. Body mass index, personality traits, and body image in Italian pre-adolescents: An opportunity for overweight prevention. Psihologija 2019, 52, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, F.; Caputo, A.; Napoli, A.; Balonan, J.T.; Martino, G.; Nannini, V.; Langher, V. Chronic illness as loss of good self: Underlying mechanisms affecting diabetes adaptation. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Miniati, M.; Fabrini, M.G.; Genovesi Ebert, F.; Mancino, M.; Maglio, A.; Massimetti, G.; Massimetti, E.; Marazziti, D. Quality of life, depression, and anxiety in patients with uveal melanoma: A review. J. Oncol. 2018, 2018, 5253109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, A.; Martino, G.; Bellone, F.; Gaudio, A.; Lasco, C.; Langher, V.; Lasco, A.; Morabito, N. Anxiety levels predict fracture risk in postmenopausal women assessed for osteoporosis. Menopause 2018, 25, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, G.; Catalano, A.; Bellone, F.; Langher, V.; Lasco, C.; Penna, A.; Nicocia, G.; Morabito, N. Quality of life in postmenopausal women: Which role for vitamin D? Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, G.; Catalano, A.; Bellone, F.; Sardella, A.; Lasco, C.; Caprì, T.; Langher, V.; Caputo, A.; Fabio, R.A.; Morabito, N. Vitamin D status is associated with anxiety levels in postmenopausal women evaluated for osteoporosis. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuluvica, C.; Fulcheri, M.; Amerio, P. Expressive suppression and negative affect, pathways of emotional dysregulation in psoriasis patients. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.R.; McDonald, L.T.; Jensen, N.R.; Sidles, S.J.; LaRue, A.C. Impacts of psychological stress on osteoporosis: Clinical implications and treatment interactions. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 443946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Marzetti, F.; Orrù, G.; Lemmetti, S.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Hitchcott, P.K.; Bazzicchi, L.; Gemignani, A.; Conversano, C. Alexithymia and psychological distress in patients with fibromyalgia and rheumatic disease. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.L.; Gargiulo, A.; Lemmo, D.; Dolce, P.; Barberio, D.; Abate, V.; Avino, F.; Tortoriello, R. Longitudinal effect of emotional processing on psychological symptoms in women under 50 with breast cancer. Health Psychol. Open 2019, 6, 2055102919844501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Romain, A.J.; Caudroit, J.; Chevance, G.; Carayol, M.; Gourlan, M.; Needham Dancause, K.; Moullec, G. Cognitive behavior therapy combined with exercise for adults with chronic diseases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Vellani, S.; Yeung, L.; Chishtie, J.; Commisso, E.; Ploeg, J.; Andrew, M.K.; Ayala, A.P.; Gray, M.; Morgan, D.; et al. Identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Du, W.; Lei, H. Commonalities and differences in psychological adjustment to chronic illnesses among older adults: A comparative study based on the stress and coping paradigm. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]