Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure the Meaning of Life (MLS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Ethical Aspects

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Preliminary Evidence of Internal Structure Validity

3.4. Validity of the Internal Structure and Reliability

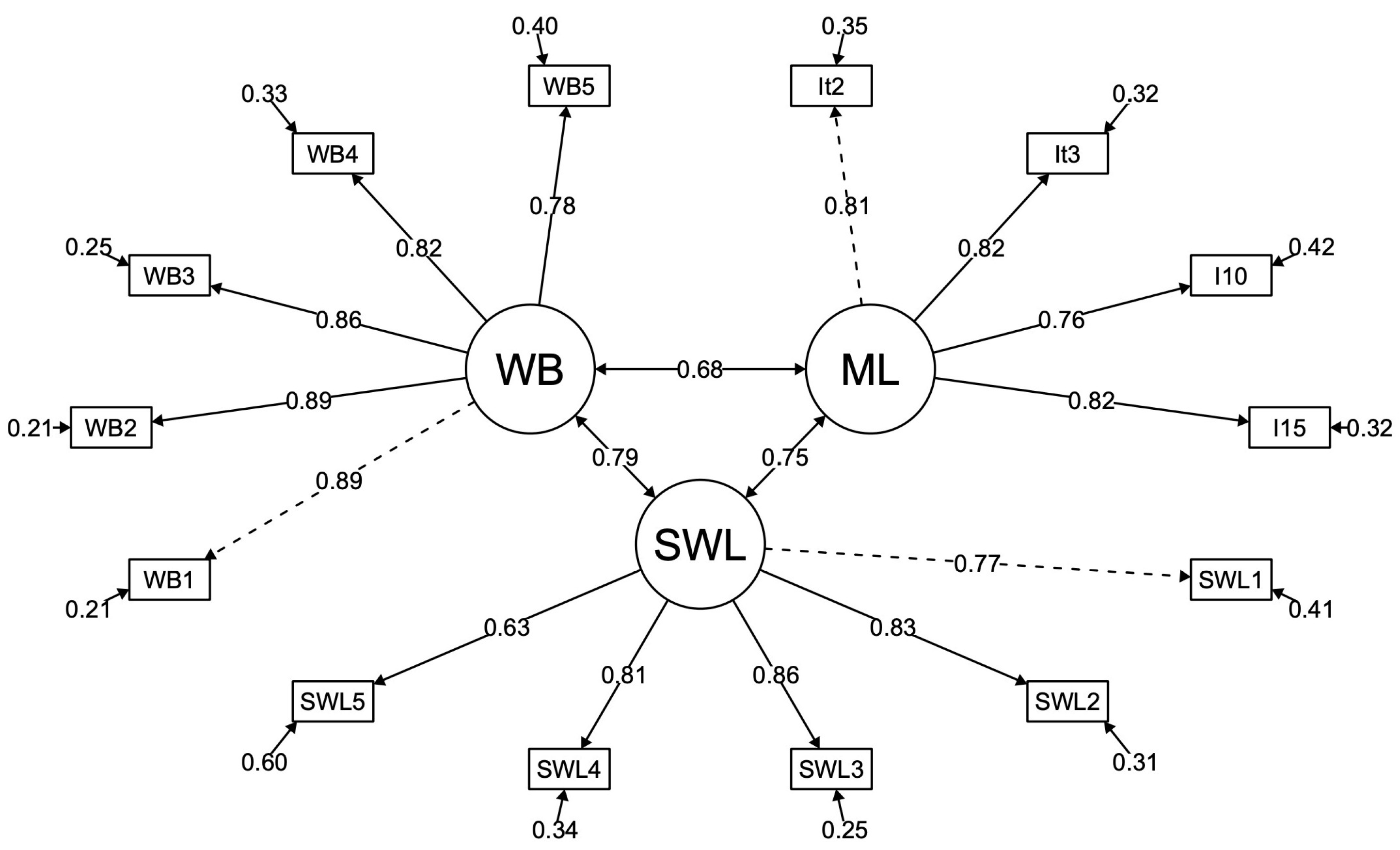

3.5. Evidence of Convergent Validity or Validity in Relation to Other Constructs

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abanto-Chávez, F. E., Aguilar-Pichón, F. M., Flores Pérez, Y. B., Navarrete-Flores, R. H., & Cruzado Saucedo, L. H. (2023). Interculturality in Peru and the process of forming an intercultural society. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 33, 5327–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L. R. (2003). Test psicológicos y evaluación (11th ed.). Pearson Educación. [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2018). Estándares para pruebas educativas y psicológicas. American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baessler, J., Oerter, R., Fernández, M. B., & Romero, E. M. (2003). Aspects of meaning of life in different subcultures in Peru. Psychological Reports, 92(3 II), 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgiu, B. A. (2020). Meaning in life questionnaire: Factor structure and gender invariance in a Romanian undergraduates sample. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(2), 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D. L., & Finney, S. J. (2019). Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In G. R. Hancock, L. M. Stapleton, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (2nd ed., pp. 98–120). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-De La Cruz, G., Lozano Chávez, F., Cantuarias Carthy, A., & Ibarra Carlos, L. (2018). Validación de la escala de satisfacción con la vida en trabajadores peruanos. Liberabit, 24(2), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Ventura-León, J., Azabache-Alvarado, K., Reyes-Bossio, M., & Cabrera-Orosco, I. (2020). Validez e invariancia factorial del Índice de Bienestar General (who-5 wbi) en universitarios peruanos. Revista Ciencias de la Salud, 18(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, E., Kim, K. H., & Erlen, J. A. (2007). Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(4), 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, V., & Vignoles, V. L. (2020). Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 864–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damásio, B. F., Helena Koller, S., & Schnell, T. (2013). Sources of meaning and meaning in life questionnaire (SoMe): Psychometric properties and sociodemographic findings in a large brazilian sample. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 3(3), 1205–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebersole, P. (1998). Types and depth of written life meanings. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 179–191). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A., Pérez, E., Alderete, A. M., Richaud, M. C., & Fernández Liporace, M. (2010). ¿Construir o adaptar tests psicológicos? diferentes respuestas a una cuestión. Evaluar, 10, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Nonnormal and categorial data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (2nd ed.). Information Age Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. E. (2023). Cross-validation in psychometrics: Advances to the state of the art [Doctoral thesis, Texas A&M University]. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/200111 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Garrison, Y. L., & Lee, K. H. (2017). Meaning in life among Korean college students based on emotionality and tolerance of uncertainty. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldemberg, I., & Zapata, M. A. (2009). An infinite country: A view of Peruvian literature and culture from the learned provinces. Review—Literature and Arts of the Americas, 42(2), 200–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Angulo, P., Salazar Mendoza, J., Castellanos Contreras, E., Camacho Martínez, J. U., Enríquez Hernández, C. B., & Conzatti Hernández, M. E. (2021). The meaning of life as a mediator between self-esteem and internet addiction in adolescentes. Revista Electrónica Trimestral de Enfermería, 20(4), 506–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hallford, D. J., Mellor, D., Cummins, R. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2018). Meaning in life in earlier and later older-adulthood: Confirmatory factor analysis and correlates of the meaning in life questionnaire. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(10), 1270–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S. A., Post, R. E., & Sherman, M. D. (2020). Awareness of meaning in life is protective against burnout among family physicians. Family Medicine, 52(1), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iso-Ahola, S. E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2023). Leisure and meaning in life. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1074649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, B., Chistopolskaya, K., Osman, A., Huen, J. M. Y., Abu Talib, M., & Leung, A. N. M. (2020). Meaning in life as a protective factor against suicidal tendencies in Chinese university students. BMC Psychiatry, 20(73), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). Exploratory item factor analysis: A practical guide revised and updated. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Ortiz, E., Trujillo Cano, Á. M., & Andrés Trujillo, C. (2012). Validación del test de propósito vital (PIL test—Purpose in life test) para Colombia. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, XXI(1), 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Maryam Hedayati, M. A., & Mahmoud Khazaei, M. A. (2014). An investigation of the relationship between depression, meaning in life and adult hope. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matesanz, A. (1997). Evaluación estructurada de la personalidad. Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Naghiyaee, M., Bahmani, B., & Asgari, A. (2020). The psychometric properties of the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ) in patients with life-threatening illnesses. Scientific World Journal, 2020, 8361602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negri, L., Bassi, M., & Delle Fave, A. (2020). Italian validation of the meaning in life questionnaire: Factor structure, reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity. Psychological Reports, 123(2), 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Penfield, R. D., & Giacobbi, P. R. (2004). Applying a score confidence interval to Aiken’s item content-relevance index. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 8(4), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reker, G. T. (2005). Meaning in life of young, middle-aged, and older adults: Factorial validity, age, and gender invariance of the Personal Meaning Index (PMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 38(1), 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L. M., Zask, A., & Burton, L. J. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) in a sample of Australian adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(1), 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Belmonte, C., Mayordomo-Rodríguez, T., Marco-Ahullo, A., & Aragonés-Barberá, I. (2024). Psychometric validation of the Purpose in Life Test-Short Form (PIL-SF) in individuals diagnosed with severe mental illness. Healthcare, 12(20), 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, J., Kosinski, M., & Stillwell, D. (2021). Modern psychometrics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye, & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T. (2009). The sources of meaning and meaning in life questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, T. (2021). The psychology of meaning in life (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T., Höge, T., & Pollet, E. (2013). Predicting meaning in work: Theory, data, implications. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2016). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Simancas-Pallares, M., Díaz-Cárdenas, S., Barbosa-Gómez, P., Buendía-Vergara, M., & Arévalo-Tovar, L. (2016). Propiedades psicométricas del Índice de Bienestar General-5 de la Organización Mundial de la Salud en pacientes parcialmente edéntulos. Revista Facultad de Medicina, 64(4), 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K., Junnarkar, M., Jaswal, S., & Kaur, J. (2016). Validation of meaning in life questionnaire in hindi (MLQ-H). Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 19(5), 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Kaler, M., & Oishi, S. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Kawabata, Y., Shimai, S., & Otake, K. (2008). The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(3), 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temane, L., Khumalo, I. P., & Wissing, M. P. (2014). Validation of the meaning in life questionnaire in a South African context. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 24(1), 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travezaño, A., Vilca, L., Quiroz, J., Huerta, S., Delgado, R., & Caycho, T. (2022). Meaning of life questionnaire (MLQ) in Peruvian undergraduate students: Study of its psychometric properties from the perspective of classical test theory (CTT). BMC Psychology, 10(1), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, F. J., Hu, Y. J., Yeh, G. L., Chen, C. Y., Tseng, C. C., & Chen, S. C. (2020). The effectiveness of a health promotion intervention on the meaning of life, positive beliefs, and well-being among undergraduate nursing students: One-group experimental study. Medicine (United States), 99(10), E19470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandenBos, G. R., & American Psychological Association. (2015). APA dictionary of psychology (G. R. VandenBos, & American Psychological Association Eds.; 2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervás, G. (2013). Satisfaction with life scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: Validation and normative data. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, E82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoriana, E., Manurung, R. T., Azizah, E., Teresa, M., & Gultom, Z. A. (2023). Makna hidup dan subjective well-being mahasiswa. Humanitas (Jurnal Psikologi), 7(2), 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. C., Furman, H., & Schulenberg, S. E. (2022). A Spanish adaptation and validation of the Purpose in Life Test—Short Form (PIL-SF). PSOCIAL, 8(1). Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=672371222012 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- WHO. (2024, January 8). Suicide mortality rate (per 100 000 population). Available online: https://data.who.int/es/indicators/i/F08B4FD/16BBF41 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- WHR. (2024). The world happiness report—2024 (J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard, J. D. Sachs, J.-E. De Neve, L. B. Aknin, & S. Wang, Eds.). University of Oxford: Wellbeing Research Centre. Available online: https://www.worldhappiness.report/ed/2024/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (1998). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the depcare project. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/349766 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi Afrashteh, M., Abbasi, M., & Abbasi, M. (2023). The relationship between meaning of life, perceived social support, spiritual well-being and pain catastrophizing with quality of life in migraine patients: The mediating role of pain self-efficacy. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. M., Zhang, M. R., Yang, C. H., & Li, Y. (2022). The meaning of life according to patients with advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17(1), 2028348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Categories | n1 = 344 (EFA) | n2 = 302 (CFA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 217 | 63.10% | 195 | 64.60% |

| Male | 127 | 36.90% | 107 | 35.40% | |

| Marital status | Married | 37 | 10.80% | 22 | 7.30% |

| Cohabitant | 18 | 5.20% | 15 | 5.00% | |

| Divorced | 3 | 0.90% | 4 | 1.30% | |

| Single | 285 | 82.80% | 257 | 85.10% | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.30% | 4 | 1.30% | |

| Department of current residence | Amazonas | 10 | 2.90% | 15 | 5.00% |

| Ancash | - | - | 2 | 0.70% | |

| Apurímac | 2 | 0.60% | - | - | |

| Ayacucho | 1 | 0.30% | 2 | 0.70% | |

| Cajamarca | 25 | 7.30% | 30 | 9.90% | |

| Callao (Constitutional Province) | - | - | 2 | 0.70% | |

| Cusco | 1 | 0.30% | - | - | |

| Huancavelica | 1 | 0.30% | - | - | |

| Huánuco | 1 | 0.30% | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Ica | 3 | 0.90% | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Junín | 1 | 0.30% | 1 | 0.30% | |

| La Libertad | 13 | 3.80% | 6 | 2.00% | |

| Lambayeque | 19 | 5.50% | 6 | 2.00% | |

| Lima | 41 | 11.90% | 14 | 4.60% | |

| Loreto | 3 | 0.90% | 10 | 3.30% | |

| Madre de Dios | 1 | 0.30% | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Moquegua | - | - | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Pasco | 1 | 0.30% | - | - | |

| Piura | 1 | 0.30% | 2 | 0.70% | |

| Puno | - | - | 2 | 0.70% | |

| San Martín | 218 | 63.40% | 197 | 65.20% | |

| Ucayali | 2 | 0.60% | 4 | 1.30% | |

| Tumbes | - | - | 5 | 1.70% | |

| Level of education | None | 2 | 0.60% | 4 | 1.30% |

| Primary | 5 | 1.50% | 2 | 0.70% | |

| High school | 34 | 9.90% | 98 | 32.50% | |

| Technician | 51 | 14.80% | 35 | 11.60% | |

| University | 252 | 73.30% | 163 | 54.00% | |

| Employment Status | Active | 145 | 42.20% | 108 | 35.8% |

| Not active | 27 | 7.80% | 24 | 7.90% | |

| Student | 172 | 50.00% | 170 | 56.30% | |

| Sample for EFA | Sample for CFA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | g1 | g2 | M | SD | g1 | g2 | |

| Item 1 | 3.96 | 1.10 | −1.32 | 1.31 | 3.92 | 0.98 | −1.08 | 1.18 |

| Item 2 | 3.92 | 1.05 | −1.13 | 1.00 | 3.97 | 0.89 | −0.92 | 1.09 |

| Item 3 | 3.93 | 1.09 | −1.19 | 0.96 | 4.07 | 0.88 | −1.02 | 1.12 |

| Item 4 | 3.80 | 1.11 | −0.93 | 0.34 | 3.92 | 0.94 | −0.76 | 0.31 |

| Item 5 | 3.73 | 1.15 | −0.85 | 0.05 | 3.73 | 1.01 | −0.65 | 0.03 |

| Item 6 | 4.16 | 1.03 | −1.60 | 2.44 | 4.10 | 0.83 | −1.03 | 1.62 |

| Item 7 | 3.85 | 1.13 | −1.01 | 0.36 | 3.98 | 0.95 | −0.97 | 0.76 |

| Item 8 | 4.15 | 1.06 | −1.60 | 2.23 | 4.27 | 0.83 | −1.42 | 2.81 |

| Item 9 | 3.92 | 1.12 | −1.14 | 0.69 | 4.03 | 0.97 | −1.13 | 1.14 |

| Item 10 | 3.88 | 1.11 | −0.94 | 0.27 | 4.04 | 0.98 | −1.08 | 0.84 |

| Item 11 | 3.97 | 1.10 | −1.28 | 1.18 | 4.03 | 0.93 | −1.11 | 1.31 |

| Item 12 | 3.88 | 1.07 | −1.14 | 1.01 | 3.99 | 0.92 | −0.99 | 0.96 |

| Item 13 | 3.83 | 1.08 | −0.98 | 0.54 | 3.94 | 0.94 | −0.90 | 0.78 |

| Item 14 | 4.01 | 1.12 | −1.30 | 1.14 | 4.11 | 0.90 | −1.15 | 1.52 |

| Item 15 | 3.92 | 1.09 | −1.10 | 0.78 | 4.00 | 0.95 | −1.04 | 1.08 |

| Item 16 | 4.10 | 1.07 | −1.48 | 1.82 | 4.14 | 0.89 | −1.32 | 2.09 |

| Item 17 | 3.95 | 1.14 | −1.21 | 0.81 | 4.10 | 0.93 | −1.17 | 1.47 |

| Item 18 | 4.01 | 1.06 | −1.30 | 1.41 | 4.12 | 0.91 | −1.22 | 1.66 |

| Initial N° | EFA | CFA | Final N° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | h2 | Factor | ||

| Item 1 | 0.847 | 0.717 | _ | _ |

| Item 2 | 0.880 | 0.774 | 0.808 | Item 1 |

| Item 3 | 0.853 | 0.728 | 0.846 | Item 2 |

| Item 4 | 0.871 | 0.758 | _ | _ |

| Item 5 | 0.841 | 0.708 | _ | _ |

| Item 6 | 0.851 | 0.725 | _ | _ |

| Item 8 | 0.814 | 0.663 | _ | _ |

| Item 10 | 0.831 | 0.691 | 0.770 | Item 3 |

| Item 11 | 0.836 | 0.699 | _ | _ |

| Item 12 | 0.864 | 0.747 | _ | _ |

| Item 13 | 0.860 | 0.740 | _ | _ |

| Item 14 | 0.914 | 0.836 | _ | _ |

| Item 15 | 0.901 | 0.812 | 0.792 | Item 4 |

| Item 16 | 0.893 | 0.797 | _ | _ |

| Item 17 | 0.881 | 0.775 | _ | _ |

| Item 18 | 0.830 | 0.689 | _ | _ |

| % of variance | 74.100 | _ | _ | |

| α | 0.979 | 0.878 | α | |

| ω | 0.979 | 0.878 | ω | |

| _ | _ | 0.972 | H | |

| _ | _ | 0.644 | AVE | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guevara-Tantalean, E.A.; Tantaleán-Arteaga, A.B.; Arévalo-García, B.F.; Cunza-Aranzábal, D.F. Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure the Meaning of Life (MLS). Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090174

Guevara-Tantalean EA, Tantaleán-Arteaga AB, Arévalo-García BF, Cunza-Aranzábal DF. Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure the Meaning of Life (MLS). European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090174

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuevara-Tantalean, Esvin Aldair, Anthony Brayham Tantaleán-Arteaga, Bruno Francesco Arévalo-García, and Denis Frank Cunza-Aranzábal. 2025. "Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure the Meaning of Life (MLS)" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090174

APA StyleGuevara-Tantalean, E. A., Tantaleán-Arteaga, A. B., Arévalo-García, B. F., & Cunza-Aranzábal, D. F. (2025). Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure the Meaning of Life (MLS). European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090174