Deficits in Duration Estimation in Individuals Aged 10–20 Years Old with Idiopathic Mild Intellectual Disability: The Role of Inhibition, Shifting, and Processing Speed

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Tasks

2.3. Evaluation of Duration Estimation Abilities

2.4. Evaluation of Inhibition Abilities

2.5. Evaluation of Shifting Abilities

2.6. Evaluation of Information Processing Speed

2.7. Computation of a Composite Score Reflecting Inhibition and Shifting

2.8. Procedure

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Duration Estimation

3.1.1. Temporal Reproduction Task

- Accuracy Score. The participants with mild intellectual disability demonstrated significantly less accuracy in the reproduction of durations. In particular, while all the participants overestimated the shortest durations (400 to 530 ms), this temporal overestimation was more marked in the participants with mild intellectual disability (0.31 ± 0.55) than in the typically developing ones (0.13 ± 0.28). Despite the accuracy score significantly differing as a function of age, none of the 2–2 comparisons showed any significant differences between the age groups (10–12 years old: 0.31 ± 0.55; 13–16 years old: 0.15 ± 0.43; and 17–20 years old: 0.20 ± 0.33).

- Variability Score. Overall, the variability score was significantly lower for the 17–20-years-old group (0.36 ± 0.17) compared to the two younger groups, which did not differ from each other (10–12 years old: 0.42 ± 0.20; 13–16 years old: 0.43 ± 0.22). Moreover, the participants with mild intellectual disability consistently showed greater variability in their temporal reproductions (0.49 ± 0.23) compared to the typically developing participants (0.31 ± 0.12).

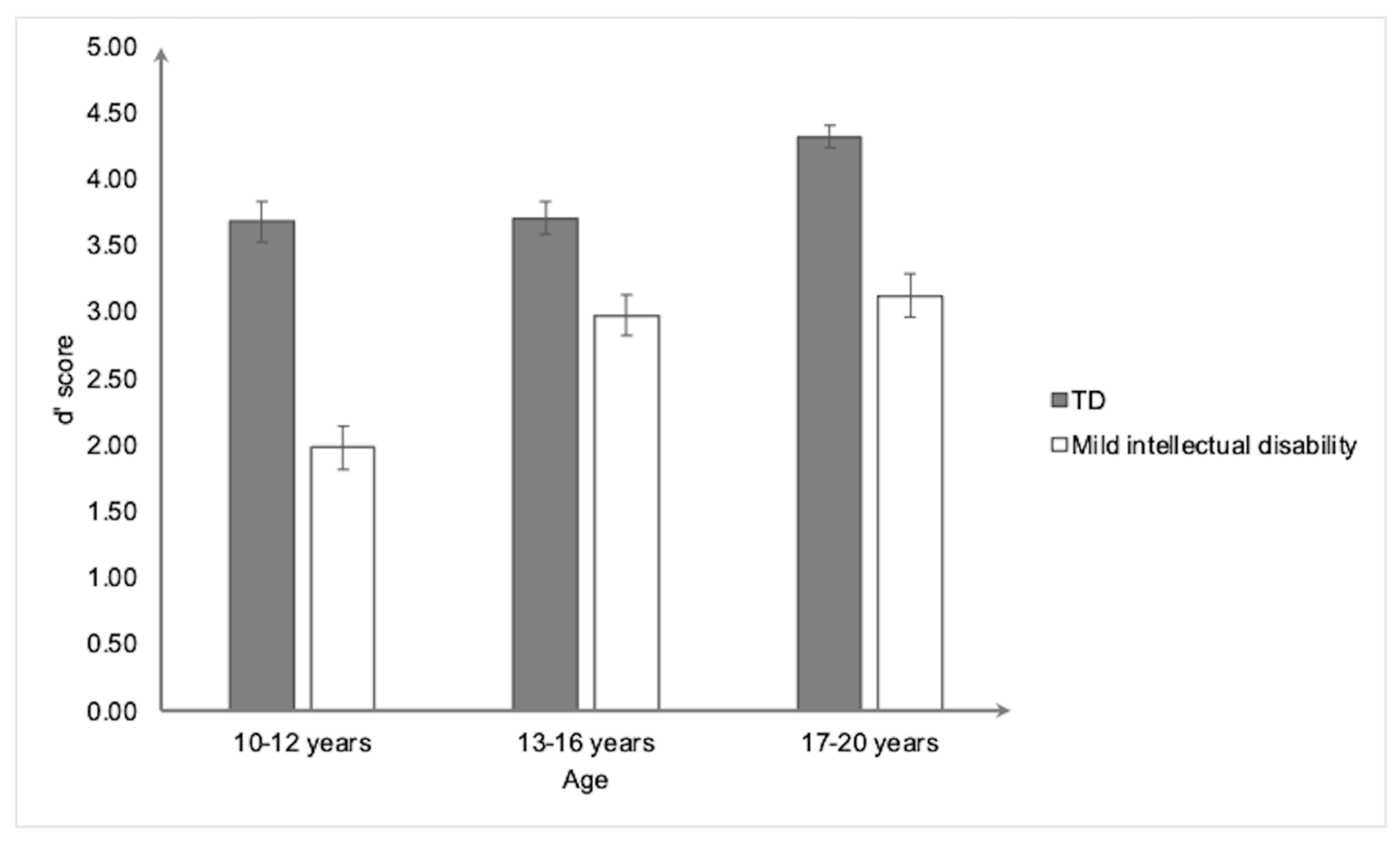

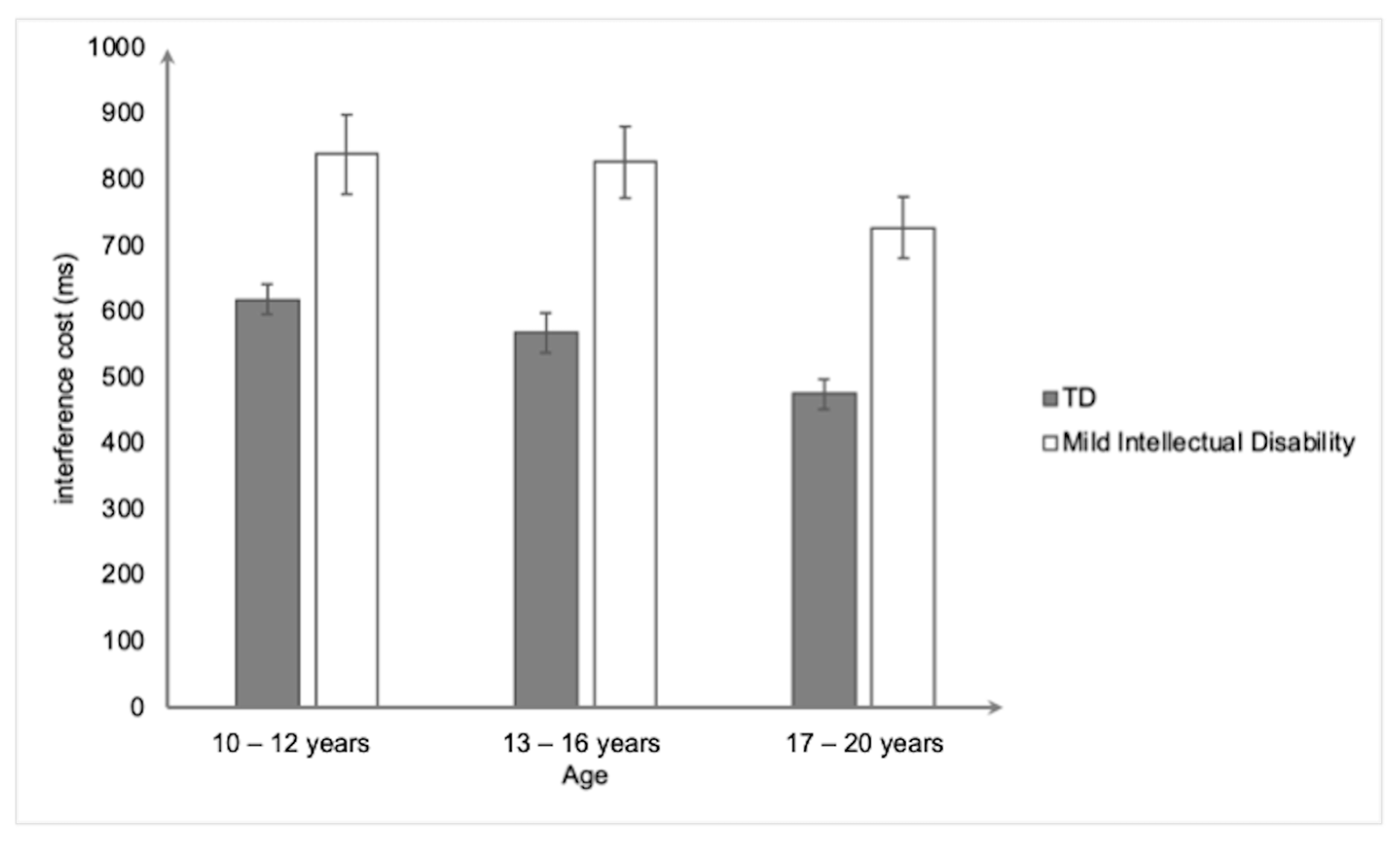

3.1.2. Executive Functions

- Inhibition. The MANCOVAs (controlling for gender) conducted on the three inhibition tasks revealed significant main effects of group (Wilks’ lambda = 0.466; F(3,146) = 57.7, p < 0.0001) and age (Wilks’ lambda = 0.738; F(6,292) = 8, p = 0.03), as well as a significant age × group interaction effect (Wilks’ lambda = 0.91; F(6,292) = 2.35, p < 0.0001). The results of the univariate ANOVAs for each task are reported below.

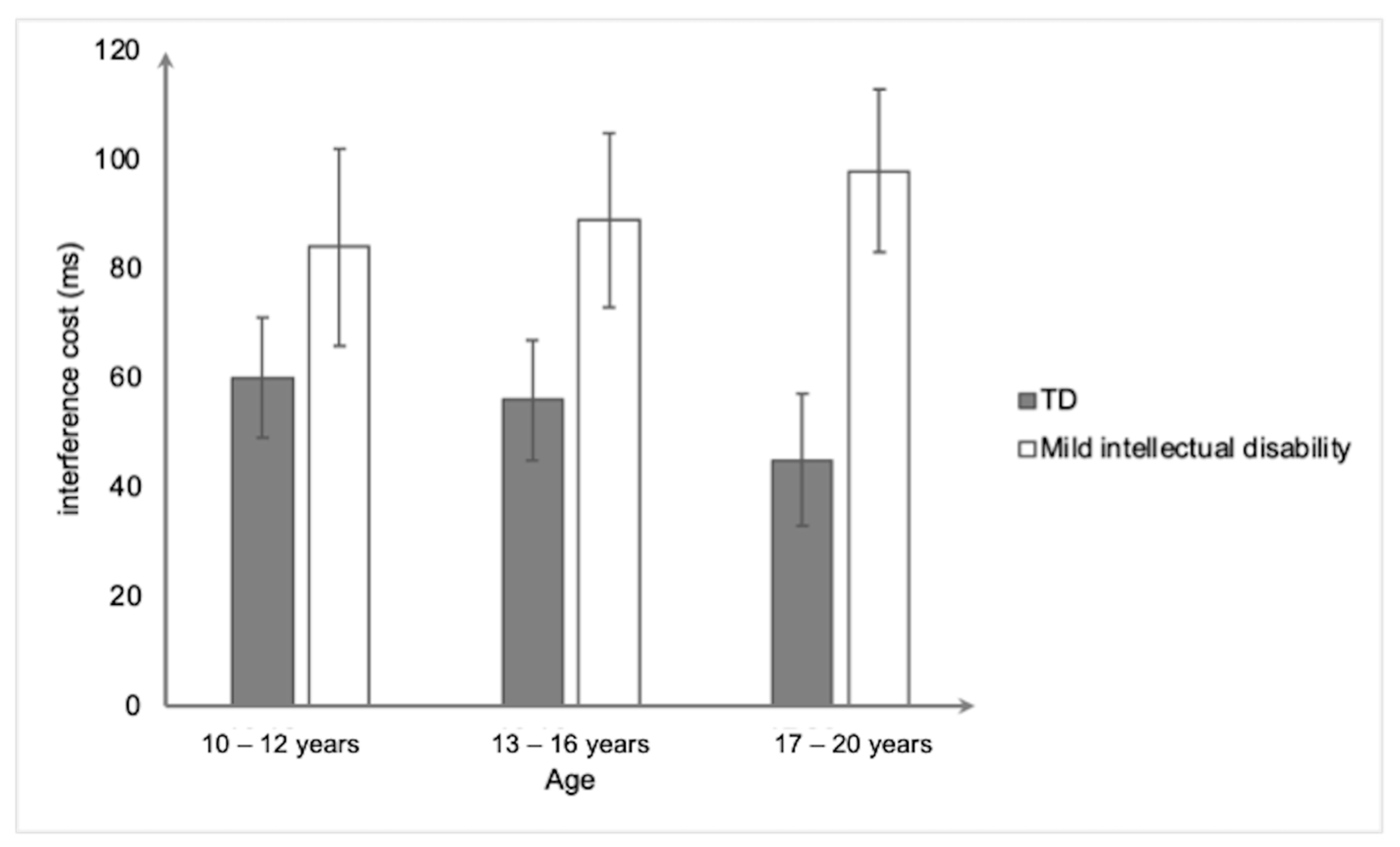

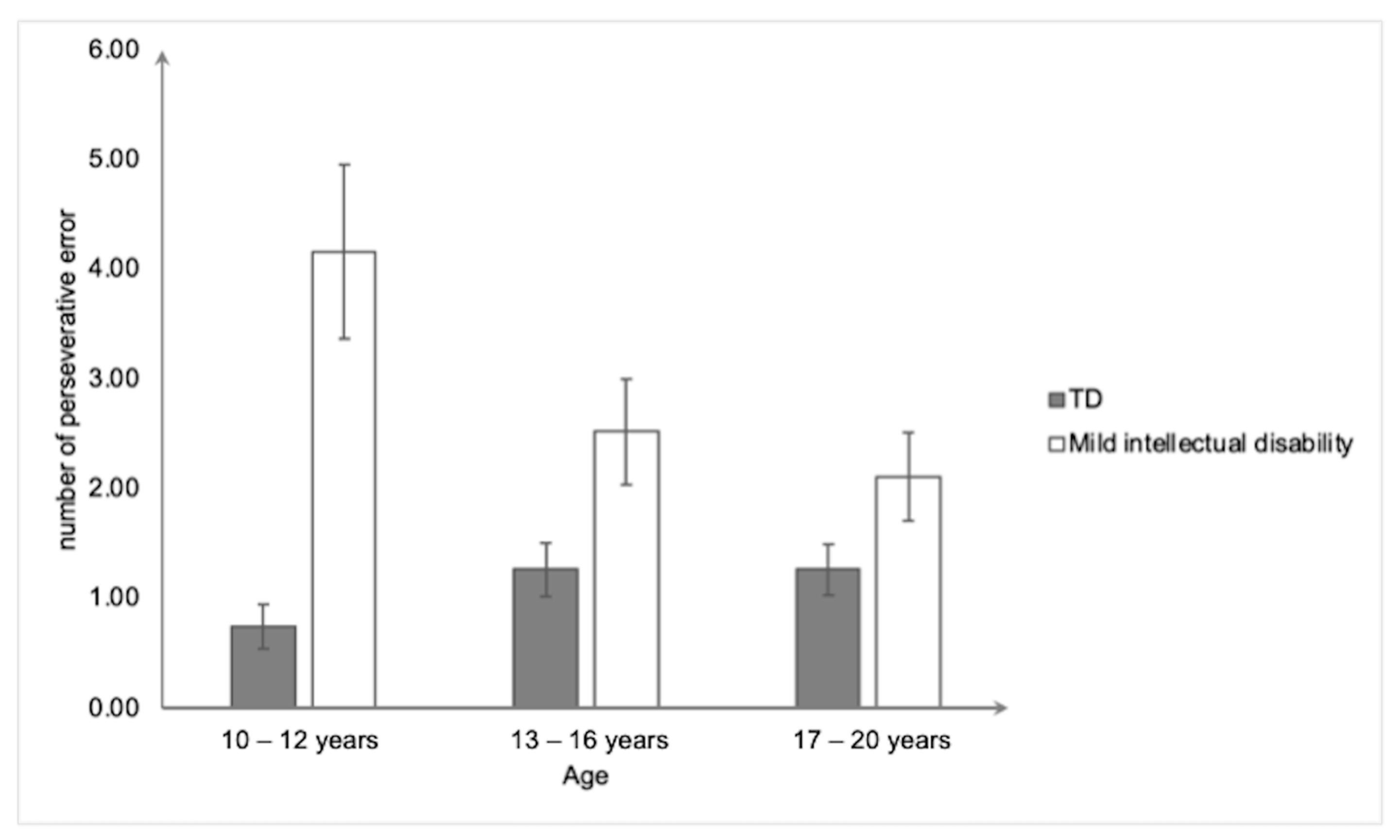

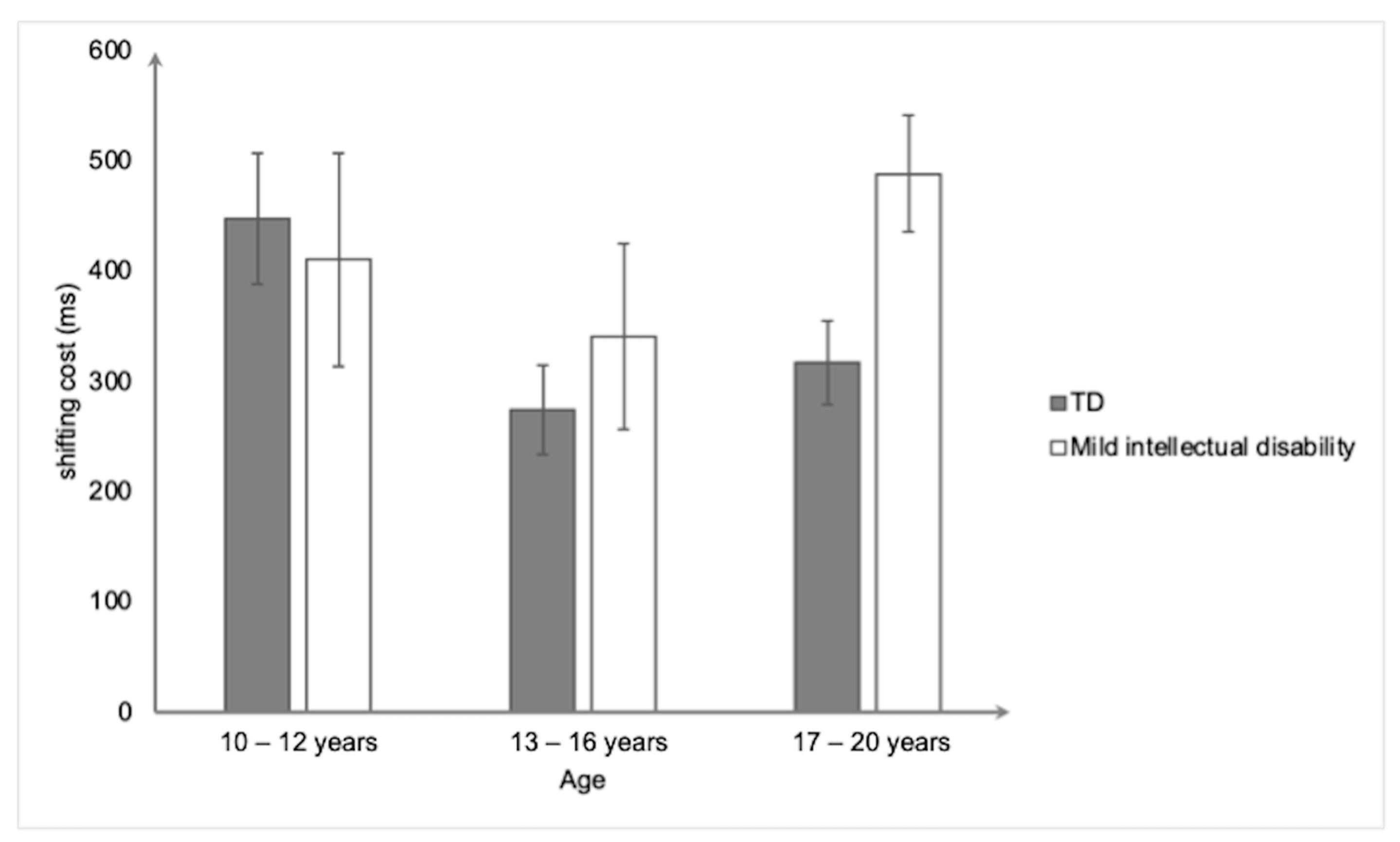

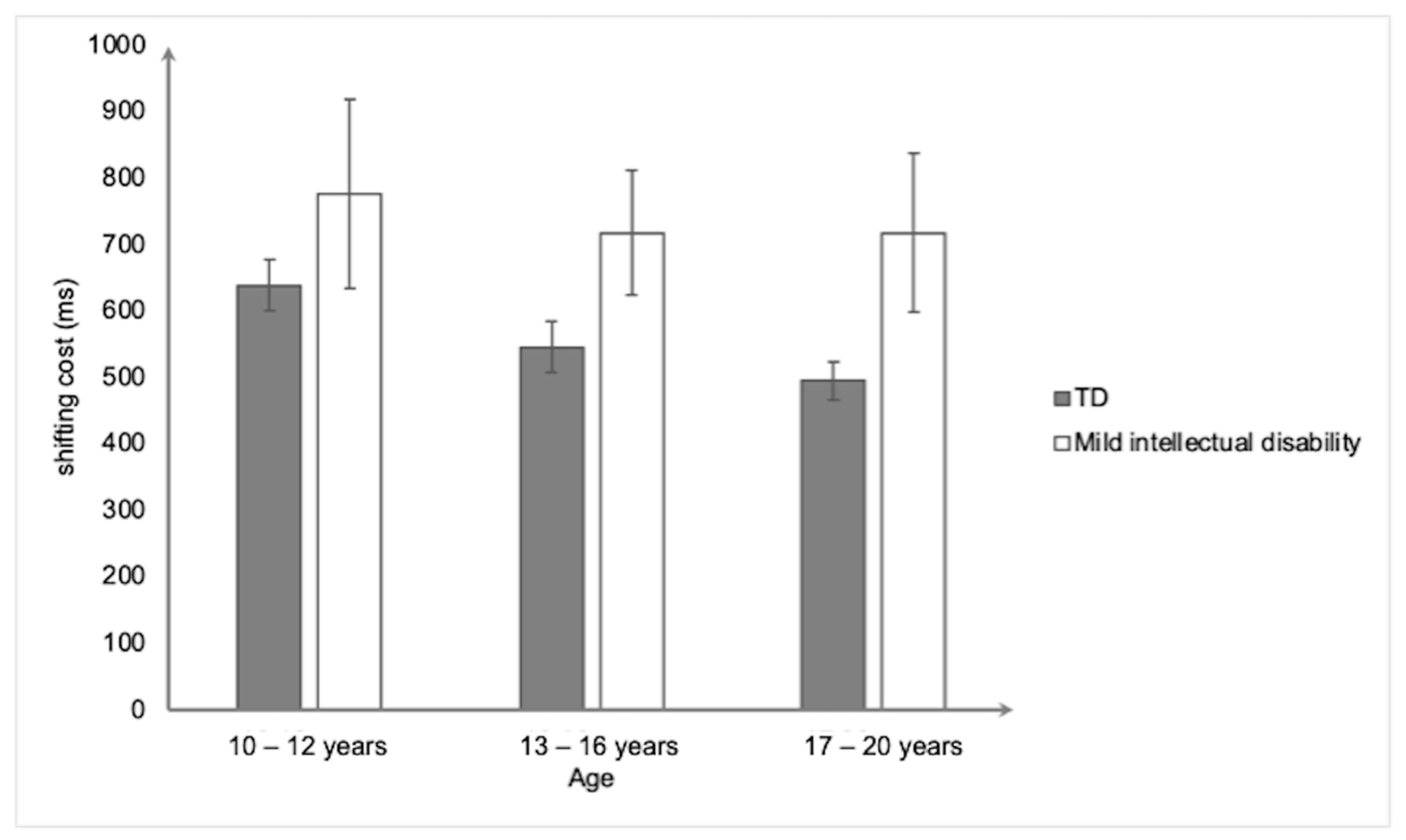

- Shifting. The MANOVAs conducted on the three shifting tasks revealed a significant main effect of group (Wilks’ lambda = 0.793; F(3,152) = 13.2, p < 0.0001). The results of the univariate ANOVAs for each task are reported below.

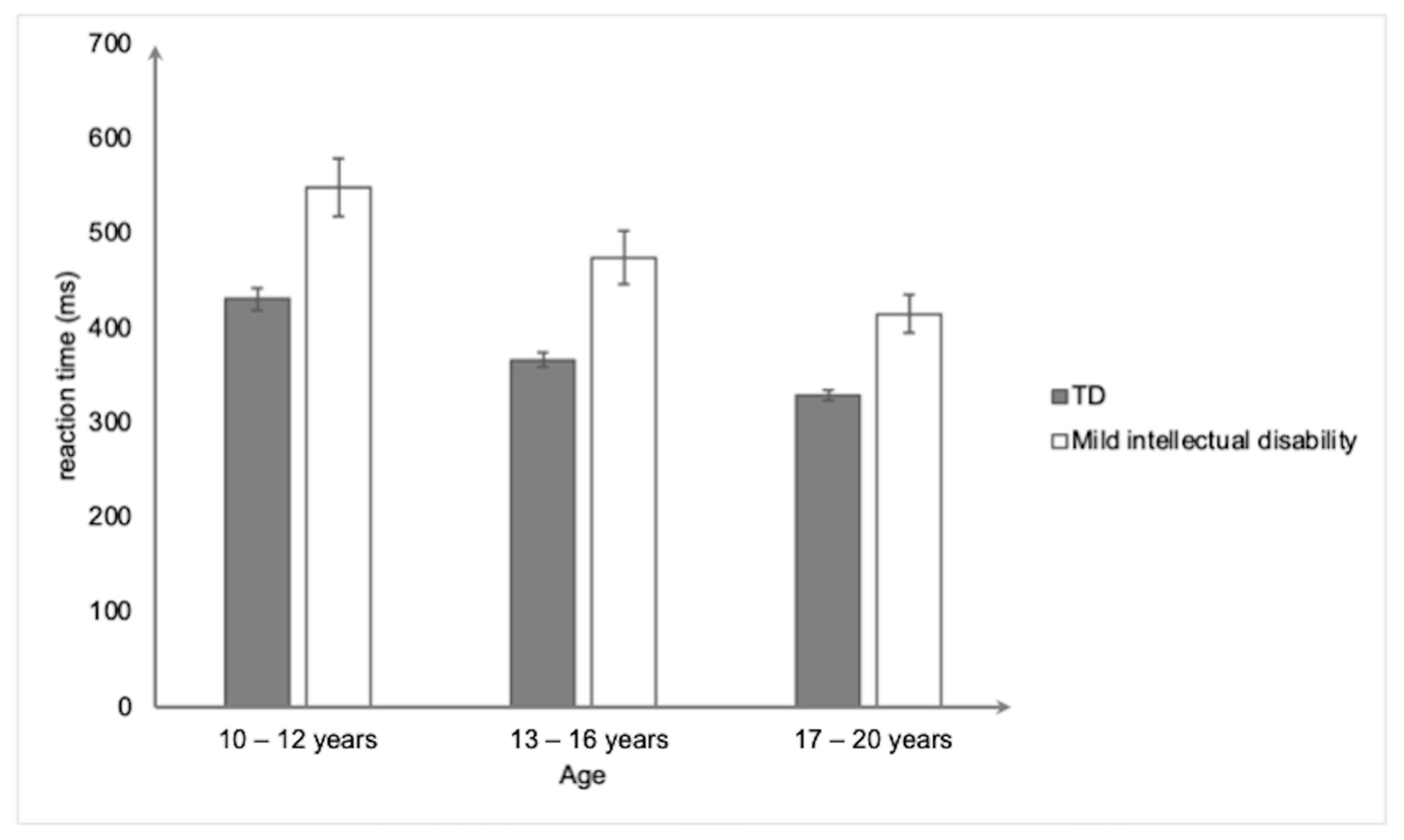

- Information processing speed. The results of the ANCOVA (controlling for gender) revealed a significant main effect of group, F(1,153) = 48.63. p < 0.001, and η2p = 0.24, showing that the participants with mild intellectual disability had a longer reaction time (478 ms ± 145) than the typically developing participants (375 ms ± 61) (Figure 7). The ANCOVA also revealed a significant main effect of age, F(2,153) = 21.26. p < 0.001, and η2p = 0.22. The post hoc analyses showed that the 17–20-year-old group had a significantly shorter reaction time compared to both the 13–16- (p < 0.05) and the 10–12 (p < 0.001)-year-old groups. These two latter groups also significantly differed from each other (p < 0.05). Finally, the group × age interaction effect was not significant (F < 1).

3.1.3. Relationship Between Duration Estimation and Cognitive Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albinet, C. T., Boucard, G., Bouquet, C. A., & Audiffren, M. (2012). Processing speed and executive functions in cognitive aging: How to disentangle their mutual relationship? Brain and Cognition, 79(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM (5th ed., pp. xliv, 947). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Bush, T. (2001). Time perception and reproduction in young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology, 15(3), 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudouin, A., Vanneste, S., Pouthas, V., & Isingrini, M. (2006). Age-related changes in duration reproduction: Involvement of working memory processes. Brain and Cognition, 62, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J. R., & Miller, P. H. (2010). A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Development, 81(6), 1641–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexkens, A., Van der Molen, M. W., Collot d’Escury-Koenigs, A. M. L., & Huizenga, H. M. (2014). Interference control in adolescents with mild-to-borderline intellectual disabilities and/or behavior disorders. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence, 20(4), 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, R. A., Hancock, P. A., & Zakay, D. (2010). How cognitive load affects duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Acta Psychologica, 134(3), 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, R. A., & Zakay, D. (1997). Prospective and retrospective duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 4(2), 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, R. A., & Zakay, D. (2006). Prospective remembering involves time estimation and memory processes. In Timing the future: The case for a time-based prospective memory (pp. 25–49). World Scientific Publishing Co. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. W. (2006). Timing and executive function: Bidirectional interference between concurrent temporal production and randomization tasks. Memory & Cognition, 34(7), 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S. W., Collier, S. A., & Night, J. C. (2013). Timing and executive resources: Dual-task interference patterns between temporal production and shifting, updating, and inhibition tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39(4), 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. W., & Frieh, C. T. (2000). Information processing in the central executive: Effects of concurrent temporal production and memory updating tasks. In P. Desain, & L. Windsor (Eds.), Rhythm perception and production (pp. 193–196). Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, G., & Shin, L. M. (2006). The multi-source interference task: An fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nature Protocols, 1(1), 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalier, N. (2010). Les fonctions exécutives chez l’enfant: Concepts et développement. [Executive functions of infants: Developmental concepts]. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 51(3), 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, N., Dauvier, B., & Blaye, A. (2018). From prioritizing objects to prioritizing cues: A developmental shift for cognitive control. Developmental Science, 21(2), e12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, N., Kelsey, K. M., Wiebe, S. A., & Espy, K. A. (2014). The Temporal dynamic of response inhibition in early childhood: An ERP study of partial and successful inhibition. Developmental Neuropsychology, 39(8), 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cianchetti, C., Corona, S., Foscoliano, M., Contu, D., & Sannio-Fancello, G. (2007). Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (MCST, MWCST): Normative data in children 4–13 years old, according to classical and new types of scoring. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, H., Henry, L., Messer, D., & Rönnberg, J. (2012). Strengths and weaknesses in executive functioning in children with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(2), 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-kaplan executive function system (D–KEFS). APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droit-Volet, S. (2010). Stop using time reproduction tasks in a comparative perspective without further analyses of the role of the motor response: The example of children. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 22(1), 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S., & Zélanti, P. S. (2013). Development of time sensitivity and information processing speed. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e71424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erostarbe-Pérez, M., Reparaz-Abaitua, C., Martínez-Pérez, L., & Magallón-Recalde, S. (2022). Executive functions and their relationship with intellectual capacity and age in schoolchildren with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 66(1–2), 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagot, B. I., & Gauvain, M. (1997). Mother-child problem solving: Continuity through the early childhood years. Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A., & Neubauer, A. C. (2005). Individual differences in time estimation related to cognitive ability, speed of information processing and working memory. Intelligence, 33(1), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, C., Schweickert, R., Gaudreault, R., & Viau-Quesnel, C. (2010). Timing is affected by demands in memory search but not by task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36(3), 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourneret, P., & des Portes, V. (2017). Approche développementale des fonctions exécutives: Du bébé à l’adolescence. Archives de Pédiatrie, 24(1), 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Corley, R. P., Young, S. E., Defries, J. C., & Hewitt, J. K. (2006). Not all executive functions are related to intelligence. Psychological Science, 17(2), 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(2), 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, T., & Droit-Volet, S. (2002). Attention and time estimation in 5- and 8-year-old children: A dual task procedure. Behavioural Processes, 58(1–2), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbon, J., Church, R. M., & Meck, W. H. (1984). Scalar timing in memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 423, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S. J., & Burgess, P. W. (2008). Executive function. Current Biology: CB, 18(3), R110–R114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gligorović, M., & Buha, N. (2013). Conceptual abilities of children with mild intellectual disability: Analysis of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 38(2), 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorović, M., & Buha Ðurović, N. (2014). Inhibitory control and adaptive behaviour in children with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(3), 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlat, E., Rattat, A.-C., & Albinet, C. T. (2024). Impact d’un entraînement cognitif sur l’estimation des durées chez des adolescents porteurs d’un Trouble du Développement Intellectuel Léger (TDIL). Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages Chez L’enfant, 192, 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Gourlat, E., Rattat, A.-C., Valéry, B., & Albinet, C. (2023). Deficits of duration estimation in individuals aged 10 to 20 years old with idiopathic mild intellectual disability: The role of updating working memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 77(9), 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grada, C., & Simoni, E. (2018). Inhibitory control of attention: Difference versus developmental theory. findings in mild intellectual disability and ADHD. Journal of Childhood & Developmental Disorders, 4(4), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravråkmo, S., Olsen, A., Lydersen, S., Ingul, J. M., Henry, L., & Øie, M. G. (2023). Associations between executive functions, intelligence and adaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 27(3), 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, Q. (2020). Développement, temps et attention: Comportements et modélisation. Bulletin de psychologie, Numéro, 566(2), 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, Q., Damsma, A., Rhodes, D., van Rijn, H., & Droit-Volet, S. (2019). The dynamic effect of context on interval timing in children and adults. Acta Psychologica, 192, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallez, Q., & Droit-Volet, S. (2017). High levels of time contraction in young children in dual tasks are related to their limited attention capacities. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 161, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmén, J., Chaplin, W., & Del Vecchio, T. (2024). Measures of executive function may not be indicators of latent constructs. Journal of Neuropsychology, 18(3), 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSERM. (2016). Déficiences intellectuelles. Inserm—La science pour la santé. Available online: https://www.inserm.fr/information-en-sante/expertises-collectives/deficiences-intellectuelles (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ionescu, T., Goldstone, R. L., Rogobete, D., & Taranu, M. (2024). Is cognitive flexibility equivalent to shifting? Investigating cognitive flexibility in multiple domains. Journal of Cognition, 7(1), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kail, R. (1992). General slowing of information-processing by persons with mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation: AJMR, 97(3), 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kail, R., & Salthouse, T. A. (1994). Processing speed as a mental capacity. Acta Psychologica, 86(2–3), 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kail, R. V., Lervåg, A., & Hulme, C. (2016). Longitudinal evidence linking processing speed to the development of reasoning. Developmental Science, 19(6), 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayanidis, F., Jamadar, S., & Sanday, D. (2013). Stimulus-level interference disrupts repetition benefit during task switching in middle childhood. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, J. E., Areshenkoff, C. N., Rast, P., Hofer, S. M., Iverson, G. L., & Garcia-Barrera, M. A. (2018). The unity and diversity of executive functions: A systematic review and re-analysis of latent variable studies. Psychological Bulletin, 144(11), 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y., Okumura, Y., Shirakawa, Y., Ikeda, Y., & Kita, Y. (2022). Characteristics of shifting ability in children with mild intellectual disabilities: An experimental study with a task-switching paradigm. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 66(11), 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K., Bull, R., & Ho, R. M. H. (2013). Developmental changes in executive functioning. Child Development, 84(6), 1933–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y., Gu, J., Zhao, K., & Fu, X. (2023). Developmental trajectory of time perception from childhood to adolescence. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24112–24122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loranger, P. M., Doyon, M., & Blais, M.-C. (2000). Mesures de vitesse des opérations mentales chez des enfants présentant une déficience intellectuelle. Revue Francophone De La Deficience Intellectuelle, 11(2), 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Maulik, P. K., Mascarenhas, M. N., Mathers, C. D., Dua, T., & Saxena, S. (2011). Prevalence of intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(2), 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S., Howlett, C. A., Berryman, C., Nedeljkovic, M., Moseley, G. L., & Phillipou, A. (2021). Considerations for using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test to assess cognitive flexibility. Behavior Research Methods, 53(5), 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J. T. (2017). Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, R. S., Mackenzie-Phelan, R., Montgomery, C., Fisk, J., & Wearden, J. (2019). Executive processes and timing: Comparing timing with and without reference memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 72, 174702181775186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, R. S., Salominaite, E., Jones, L. A., Fisk, J. E., & Montgomery, C. (2011). The role of executive functions in human prospective interval timing. Acta Psychologica, 137(3), 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, R. S., Wearden, J. H., & Montgomery, C. (2014). The differential contribution of executive functions to temporal generalisation, reproduction and verbal estimation. Acta Psychologica, 152, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S. V., Srinivas, S. B., Tussing, D. V., & Rhee, J. (2025). Addressing the flexible use of cognitive flexibility constructs: Toward a multifaceted approach. Academy of Management Annals, 19(1), 74–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perbal, S., Droit-Volet, S., Isingrini, M., & Pouthas, V. (2002). Relationships between age-related changes in time estimation and age-related changes in processing speed, attention, and memory. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 9(3), 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbitt, P. (Ed.). (1997). Methodology of frontal and executive function. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammsayer, T. H., & Brandler, S. (2007). Performance on temporal information processing as an index of general intelligence. Intelligence, 35(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattat, A.-C. (2010). Bidirectional interference between timing and concurrent memory processing in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 106(2–3), 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattat, A.-C., & Chevalier, N. (2020). The different contribution of executive control to temporal comparison and reproduction in children and adults. Journal of Cognition and Development, 21(5), 754–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattat, A.-C., & Collié, I. (2020). Duration judgments in children and adolescents with and without mild intellectual disability. Heliyon, 6(11), e05514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raud, L., Westerhausen, R., Dooley, N., & Huster, R. J. (2020). Differences in unity: The go/no-go and stop signal tasks rely on different mechanisms. NeuroImage, 210, 116582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, K. P., Wong, E. H., & Looney, L. (2023). The psychometric structure of executive functions: A satisfactory measurement model? An examination using meta-analysis and network modeling. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103(3), 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuiringa, H., van Nieuwenhuijzen, M., Orobio de Castro, B., & Matthys, W. (2017). Executive functions and processing speed in children with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities and externalizing behavior problems. Child Neuropsychology, 23(4), 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, M., & Danielsson, H. (2022). A meta-analysis of the executive function components inhibition, shifting, and attention in intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 66(1–2), 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y., DesRuisseaux, L. A., Mora, M. G., Brothers, S. L., & Niermeyer, M. A. (2024a). Conceptualization of the term “ecological validity” in neuropsychological research on executive function assessment: A systematic review and call to action. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 30(5), 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y., Mora, M. G., DesRuisseaux, L. A., Niermeyer, M. A., & Brothers, S. L. (2024b). Pitfalls in research on ecological validity of novel executive function tests: A systematic review and a call to action. Psychological Assessment, 36(4), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo-Clemmens, B., Calabro, F. J., Parr, A. C., Fedor, J., Foran, W., & Luna, B. (2023). A canonical trajectory of executive function maturation from adolescence to adulthood. Nature Communications, 14(1), 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, T. E., McGeown, S. P., Rhodes, S. M., & MacPherson, S. E. (2020). Developmental changes in executive functions during adolescence: A study of inhibition, shifting, and working memory. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 38(1), 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treillet, V., Jourdan-Ionescu, C., & Blanchette, I. (2014). Compréhension des émotions et inhibition chez des enfants avec ou sans déficience intellectuelle. Revue Francophone de la Déficience Intellectuelle, 25, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Molen, M. J., Van Luit, J. E. H., Jongmans, M. J., & Van der Molen, M.-W. (2007). Verbal working memory in children with mild intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(2), 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallisch, A., Little, L. M., Dean, E., & Dunn, W. (2018). Executive function measures for children: A scoping review of ecological validity. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 38(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearden, J. H. (2003). Applying the scalar timing model to human time psychology: Progress and challenges. In Time and mind II: Information processing perspectives (pp. 21–39). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wearden, J. H., O’Rourke, S. C., Matchwick, C., Min, Z., & Maeers, S. (2010). Task switching and subjective duration. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (2006), 63(3), 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J., Crowe, L. M., Dooley, J., Collie, A., Davis, G., McCrory, P., Clausen, H., Maddocks, D., & Anderson, V. (2016). Developmental trajectory of information-processing skills in children: Computer-based assessment. Applied Neuropsychology. Child, 5(1), 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, J. W., O’Laughlin, K. D., Anguera, J. A., Bunge, S. A., Ferrer, E. E., Hoeft, F., McCandliss, B. D., Mishra, J., Rosenberg-Lee, M., Gazzaley, A., & Uncapher, M. R. (2023). Better together: Novel methods for measuring and modeling development of executive function diversity while accounting for unity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1195013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagaria, T., Antonucci, G., Buono, S., Recupero, M., & Zoccolotti, P. (2021). Executive functions and attention processes in adolescents and young adults with intellectual disability. Brain Sciences, 11(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zélanti, P. S., & Droit-Volet, S. (2011). Cognitive abilities explaining age-related changes in time perception of short and long durations. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 109(2), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GROUP | AGE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–12 Years Old | 13–16 Years Old | 17–20 Years Old | |

| Typically developing | |||

| N | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| % boys (n) | 51.85 (14) | 67.00 (18) | 18.52 (5) |

| mean age | 11.22 | 13.56 | 18.63 |

| sd | 0.64 | 0.89 | 1.11 |

| Mild Intellectual Disability | |||

| N | 25 | 27 | 27 |

| % boys (n) | 76.00 (19) | 59.26 (16) | 55.56 (15) |

| mean age | 10.76 | 14.56 | 18.11 |

| sd | 0.93 | 1.15 | 0.85 |

| Variables | Accuracy Score | Variability Score |

|---|---|---|

| GNG | r = −0.34 *** | r = −0.46 *** |

| MIT | r = 0.083 | r = −0.21 * |

| RAST | r = −0.087 | r = −0.14 |

| WCST | r = 0.075 | r = 0.26 *** |

| ARTS | r = −0.069 | r = 0.06 |

| CTS | r = −0.005 | r = 0.14 |

| CRT | r = 0.49 *** | r = 0.39 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gourlat, E.; Rattat, A.-C.; Albinet, C.T. Deficits in Duration Estimation in Individuals Aged 10–20 Years Old with Idiopathic Mild Intellectual Disability: The Role of Inhibition, Shifting, and Processing Speed. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080156

Gourlat E, Rattat A-C, Albinet CT. Deficits in Duration Estimation in Individuals Aged 10–20 Years Old with Idiopathic Mild Intellectual Disability: The Role of Inhibition, Shifting, and Processing Speed. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(8):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080156

Chicago/Turabian StyleGourlat, Elsa, Anne-Claire Rattat, and Cédric T. Albinet. 2025. "Deficits in Duration Estimation in Individuals Aged 10–20 Years Old with Idiopathic Mild Intellectual Disability: The Role of Inhibition, Shifting, and Processing Speed" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 8: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080156

APA StyleGourlat, E., Rattat, A.-C., & Albinet, C. T. (2025). Deficits in Duration Estimation in Individuals Aged 10–20 Years Old with Idiopathic Mild Intellectual Disability: The Role of Inhibition, Shifting, and Processing Speed. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(8), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080156