Nonzero-Sum Time Perception Is Associated with Greater Willingness to Help

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Time as Zero-Sum Versus Nonzero-Sum

1.2. Time Perception and Willingness to Help

1.3. Overview of Present Research

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Study 1

2.1.2. Study 2

2.1.3. Study 3

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Study 1

2.2.2. Study 2

2.2.3. Study 3

3. Results

3.1. Study 1

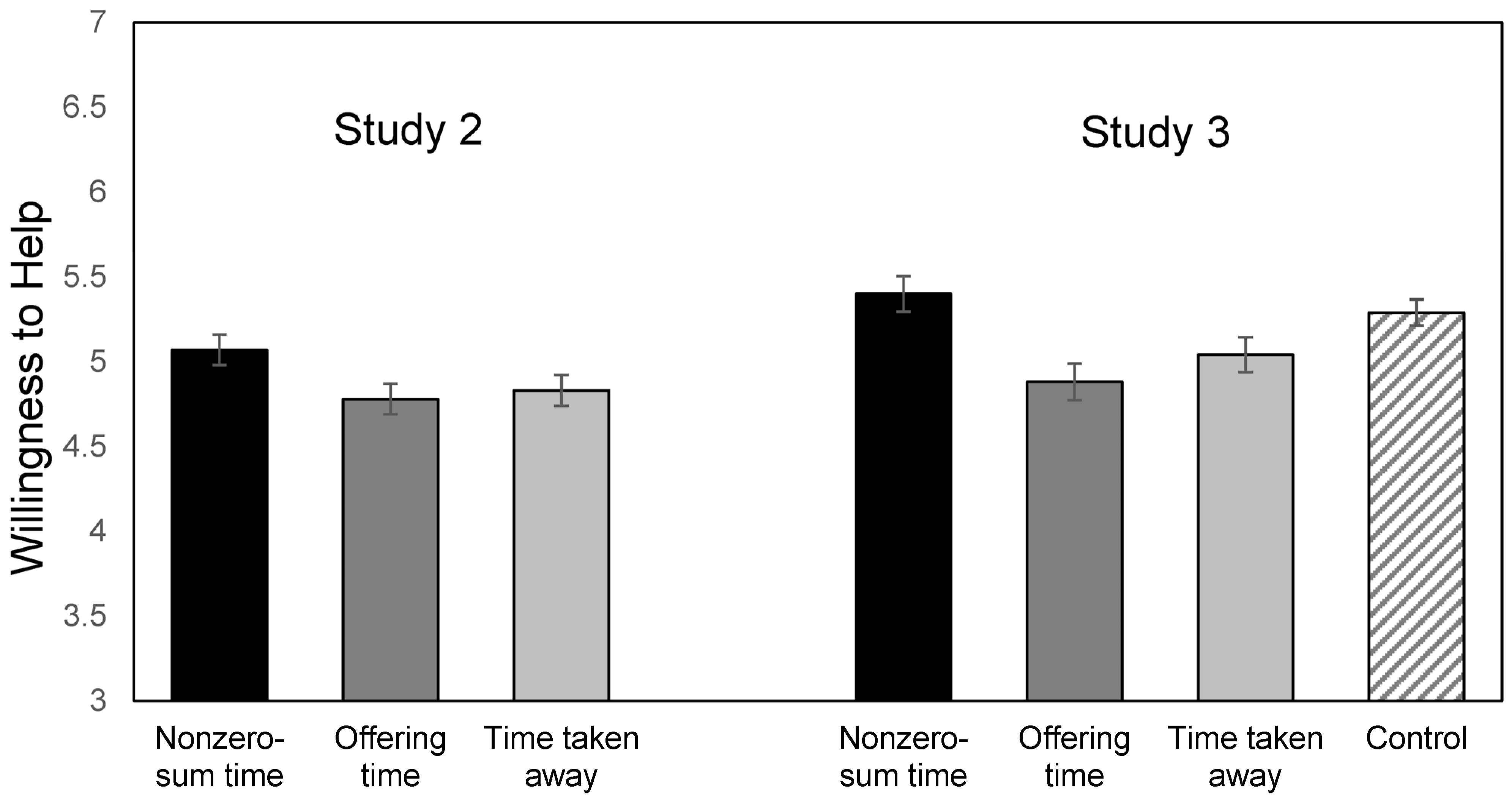

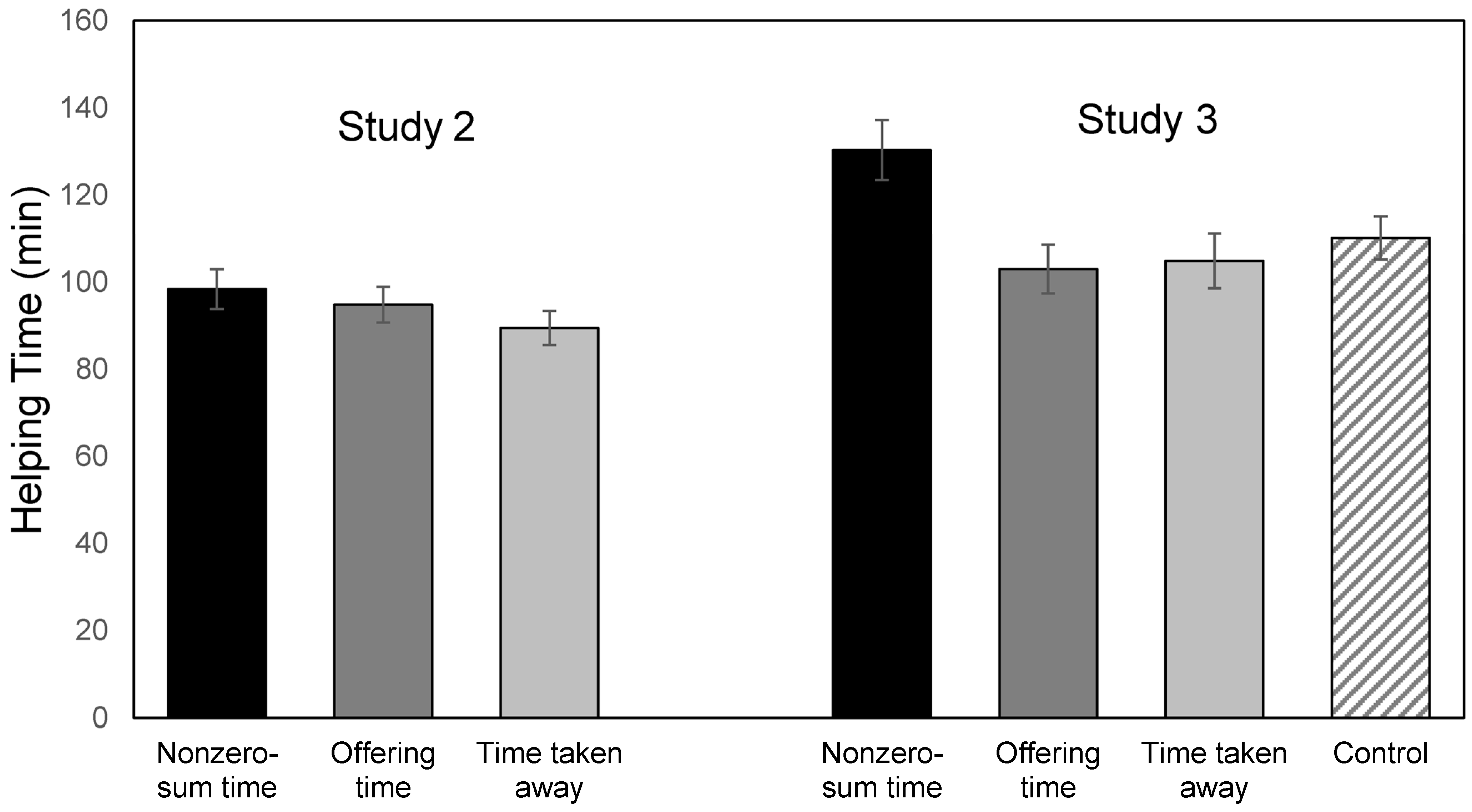

3.2. Study 2

3.3. Study 3

3.3.1. Manipulation Checks

3.3.2. Willingness to Help and Time Spent Helping

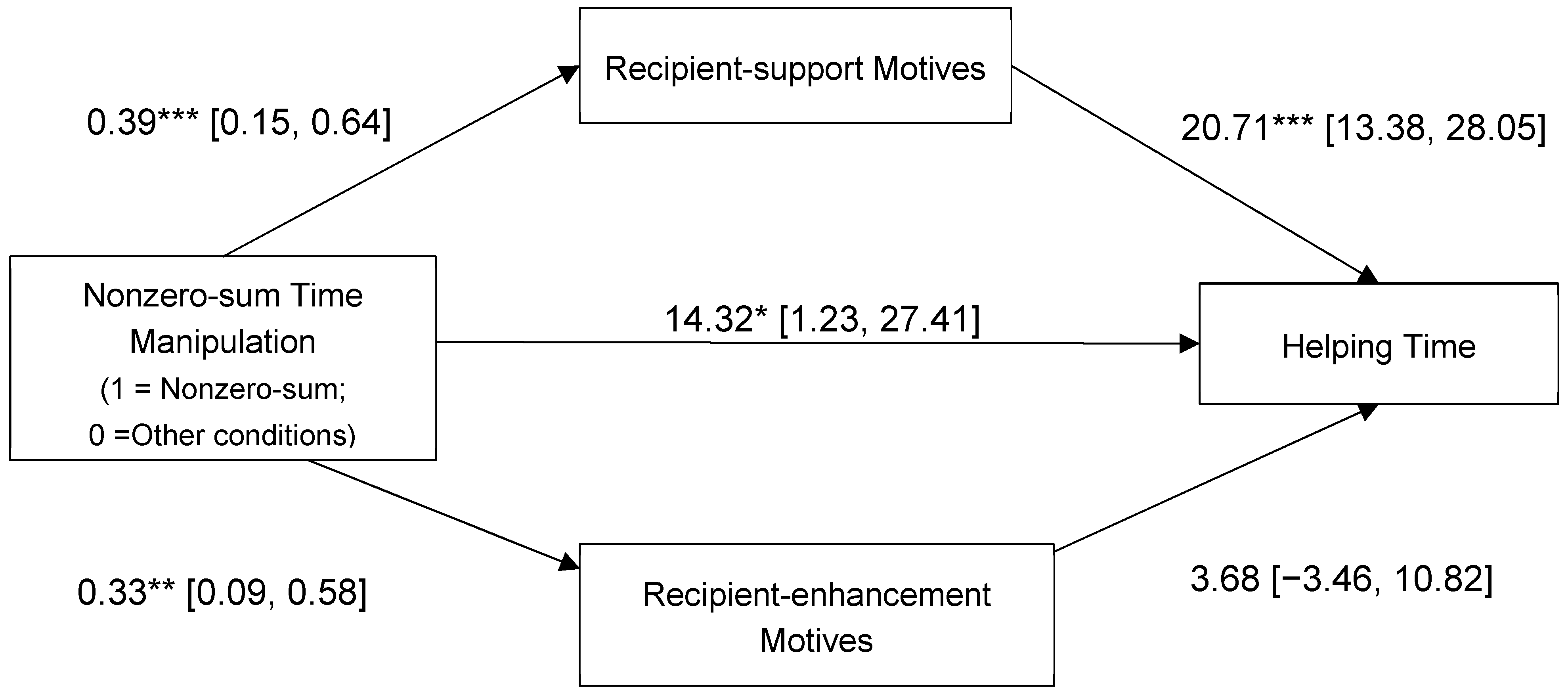

3.3.3. Indirect Effects of Nonzero-Sum Time Manipulation

3.3.4. Indirect Effects of Offering Time on Helping

4. General Discussion

4.1. Nonzero-Sum Time Perception and Helping

4.2. Perceptions of Offering Time and Helping

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Vignette 1 (Study 1)

- Vignette 2 (Study 1)

- Vignette 3 (Studies 1, 2, and 3)

| 1 | Time and money differ in that spending money on oneself results in having less money for oneself, whereas spending time on oneself makes one feel that one has more time for the self. |

| 2 | Target sample size was determined based on the needs of the larger study. |

| 3 | Data were collected in 2019 around the time of the warning that automated bots were found to harm data quality on MTurk (Stokel-Walker, 2018). We therefore tried to ensure data quality by including three attention check items asking participants to select a specific value on Likert scales (e.g., “If you are reading this statement, please select ‘Slightly’ as your answer”) and three items asking participants to select the correct information provided in the vignettes (e.g., “Based on the vignette, what was the task assigned by your supervisor?”). The number of participants who failed our attention check questions was higher than usual because participants needed to correctly answer all six attention check items to be included in the analyses. |

| 4 | We do not believe that the period of COVID-19 moderated our main findings, as we conducted our studies before (Study 1), during (Study 2), and at the end of the pandemic (Study 3) and replicated consistent patterns of results. However, the risks of infection during the pandemic may have diminished participants’ willingness to interact with others in Study 2. Indeed, for the same vignette, the average helping time in Study 2 was shorter (M = 94.23, SD = 52.74) than in Study 3, which was conducted toward the end of the pandemic (M = 111.46, SD = 67.99), and Study 1, which was conducted before the pandemic (M = 119.83, SD = 65.99). |

| 5 | The Time Perception Scale also included two items assessing the perception of taking time from others (e.g., “I feel that I am taking away other people’s time;” r = 0.87) but these items were excluded from analyses because they were irrelevant in the context of helping others. |

| 6 | Separate analyses for each item produced the same results as using the combined index for willingness to help. |

| 7 | Four participants failed to complete the Time Perception Scale, so analyses were based on n = 530. However, their data were included in the main analyses since they completed the manipulation, main dependent variables, and mediators. |

References

- Andrews Fearon, P., & Götz, F. M. (2024). The zero-sum mindset. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 127(4), 758–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. D. (2011). Altruism in humans. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprariello, P. A., & Reis, H. T. (2021). ‘This one’s on me!’: Differential well-being effects of self-centered and recipient-centered motives for spending money on others. Motivation and Emotion, 45(6), 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardador, M. T., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2015). Better to give and to compete? Prosocial and competitive motives as interactive predictors of citizenship behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(3), 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak-Hai, L., & Davidai, S. (2022). “Do not teach them how to fish”: The effect of zero-sum beliefs on help giving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(10), 2466–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. S., Mills, J., & Powell, M. C. (1986). Keeping track of needs in communal and exchange relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(2), 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, S., & Molho, C. (2022). Subjective interdependence and prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, S., Molho, C., Righetti, F., & Balliet, D. (2021). Interdependence and cooperation in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(3), 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C. E., Ford, D. P., Turel, O., Gallupe, B., & Zweig, D. (2014). ‘I’m busy (and competitive)!’ Antecedents of knowledge sharing under pressure. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 12(1), 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2015). Relationships and the self: Egosystem and ecosystem. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 93–116). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J., Canevello, A., & Lewis, K. A. (2017). Romantic relationships in the ecosystem: Compassionate goals, nonzero-sum beliefs, and change in relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(1), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darley, J. M., & Batson, C. D. (1973). “From Jerusalem to Jericho”: A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27(1), 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Gaertner, S. L., Schroeder, D. A., & Clark, R. D., III. (1991). The arousal: Cost-reward model and the process of intervention: A review of the evidence. In M. S. Clark (Ed.), Prosocial behaviors (pp. 86–118). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2014). Prosocial spending and happiness: Using money to benefit others pays off. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. t., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskreis-Winkler, L., Fishbach, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2018). Dear Abby: Should I give advice or receive it? Psychological Science, 29(11), 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsche, B. A., Finkelstein, M. A., & Penner, L. A. (2000). To help or not to help: Capturing individuals’ decision policies. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 28(6), 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Zhang, N., Sun, X., Liu, Z., & Wang, Y. L. (2024). Being pressed for time leads to treating others as things: Exploring the relationships among time scarcity, agentic and communal orientation and objectification. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 63, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, H., & Sivanathan, N. (2022). The impact of leader dominance on employees’ zero-sum mindset and helping behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(10), 1706–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karau, S. J., & Kelly, J. R. (1992). The effects of time scarcity and time abundance on group performance quality and interaction process. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28(6), 542–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cognitive Science, 4(2), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(2), 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., & Hui, C.-M. (2019). The roles of communal motivation in daily prosocial behaviors: A dyadic experience sampling study. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(8), 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luberto, C. M., Shinday, N., Song, R., Philpotts, L. L., Park, E. R., Fricchione, G. L., & Yeh, G. Y. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and prosocial behaviors. Mindfulness, 9(3), 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C., Chance, Z., & Norton, M. I. (2012). Giving time gives you time. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiya, Y. (2019). My time, your time, or our time? Time perception and its associations with interpersonal goals and life outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(5), 1439–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiya, Y., & Suyama, M. (2023). Time for you and for me: Compassionate goals predict greater psychological well-being via the perception of time as nonzero-sum resources. The Journal of Social Psychology, 164(5), 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiya, Y., & Yakin, S. (2024). Compassionate goals are associated with a greater willingness to help through a nonzero-sum mindset. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17198–17212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavey, L., Greitemeyer, T., & Sparks, P. (2011). Highlighting relatedness promotes prosocial motives and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliavin, J. A. (1991). Is the road to helping paved with good intentions? Or inertia? In J. A. Howard, & P. L. Callero (Eds.), The self-society dynamic: Cognition, emotion, and action (pp. 259–279). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention—Behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, N., & Pitesa, M. (2017). Economic downturns undermine workplace helping by promoting a zero-sum construal of success. The Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1339–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C. (2018). Bots on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk are ruining psychology studies. New Scientist. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2176436-bots-on-amazons-mechanical-turk-are-ruining-psychology-studies/ (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Škerlavaj, M., Connelly, C. E., Cerne, M., & Dysvik, A. (2018). Tell me if you can: Time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(7), 1489–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T. J., Stanton, A. L., Austin, J. E., Valdimarsdottir, H. B., Wu, L. M., Krull, J. L., & Rini, C. M. (2017). Helping yourself by offering help: Mediators of expressive helping in survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(5), 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakin, S., & Niiya, Y. (2023). Time perception scale: Measurement invariance between the U.S. and Japan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 27(3), 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonzero-Sum Time (n = 109) | Offering Time (n = 122) | Time-Taken-Away (n = 118) | Control (n = 181) 1 | |

| Nonzero-sum time | 4.17 (0.89) | 2.50 *** (1.05) | 2.46 *** (1.11) | 2.22 *** (1.20) |

| Offering time | 3.10 *** (1.18) | 3.86 (0.89) | 3.61 (0.99) | 1.95 *** (1.08) |

| Time-taken-away | 1.28 *** (0.69) | 3.07 ** (1.43) | 3.47 (1.25) | 1.56 *** (1.02) |

| Condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonzero-Sum Time (n = 110) | Offering Time (n = 123) | Time-Taken-Away (n = 120) | Control (n = 181) 1 | |

| Willingness to help | 5.40 (1.11) | 4.88 *** (1.19) | 5.05 * (1.14) | 5.29 (1.03) |

| Time allocated to help | 130.27 (72.33) | 102.97 ** (61.87) | 104.89 ** (68.96) | 110.14 * (66.98) |

| Recipient-enhancement motives | 4.76 (1.11) | 4.39 * (1.12) | 4.49 (1.31) | 4.40 * (1.18) |

| Recipient-support motives | 5.33 (1.03) | 4.93 ** (1.08) | 4.99 * (1.20) | 4.92 ** (1.23) |

| Relationship closeness | 3.46 (1.41) | 3.07 * (1.25) | 3.26 (1.31) | 3.08 * (1.29) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niiya, Y.; Yakin, S.; Park, L.E.; Chang, Y.-H. Nonzero-Sum Time Perception Is Associated with Greater Willingness to Help. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050090

Niiya Y, Yakin S, Park LE, Chang Y-H. Nonzero-Sum Time Perception Is Associated with Greater Willingness to Help. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiiya, Yu, Syamil Yakin, Lora E. Park, and Ya-Hui Chang. 2025. "Nonzero-Sum Time Perception Is Associated with Greater Willingness to Help" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050090

APA StyleNiiya, Y., Yakin, S., Park, L. E., & Chang, Y.-H. (2025). Nonzero-Sum Time Perception Is Associated with Greater Willingness to Help. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050090