The Relationship Between Social Problem-Solving and Passive-Aggressive Behavior Among Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Collection and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Age and Sex Differences

3.2. Correlation Analysis

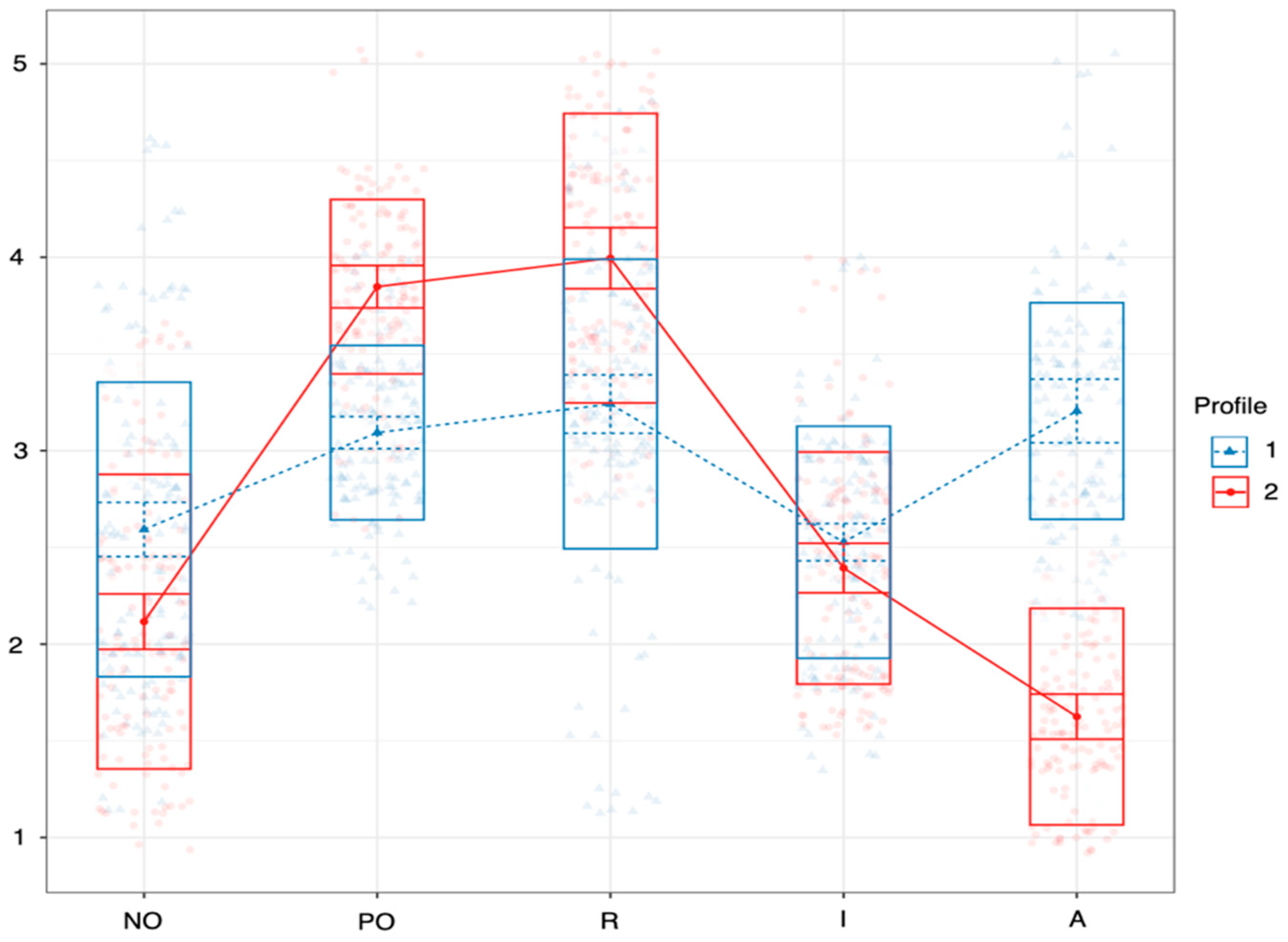

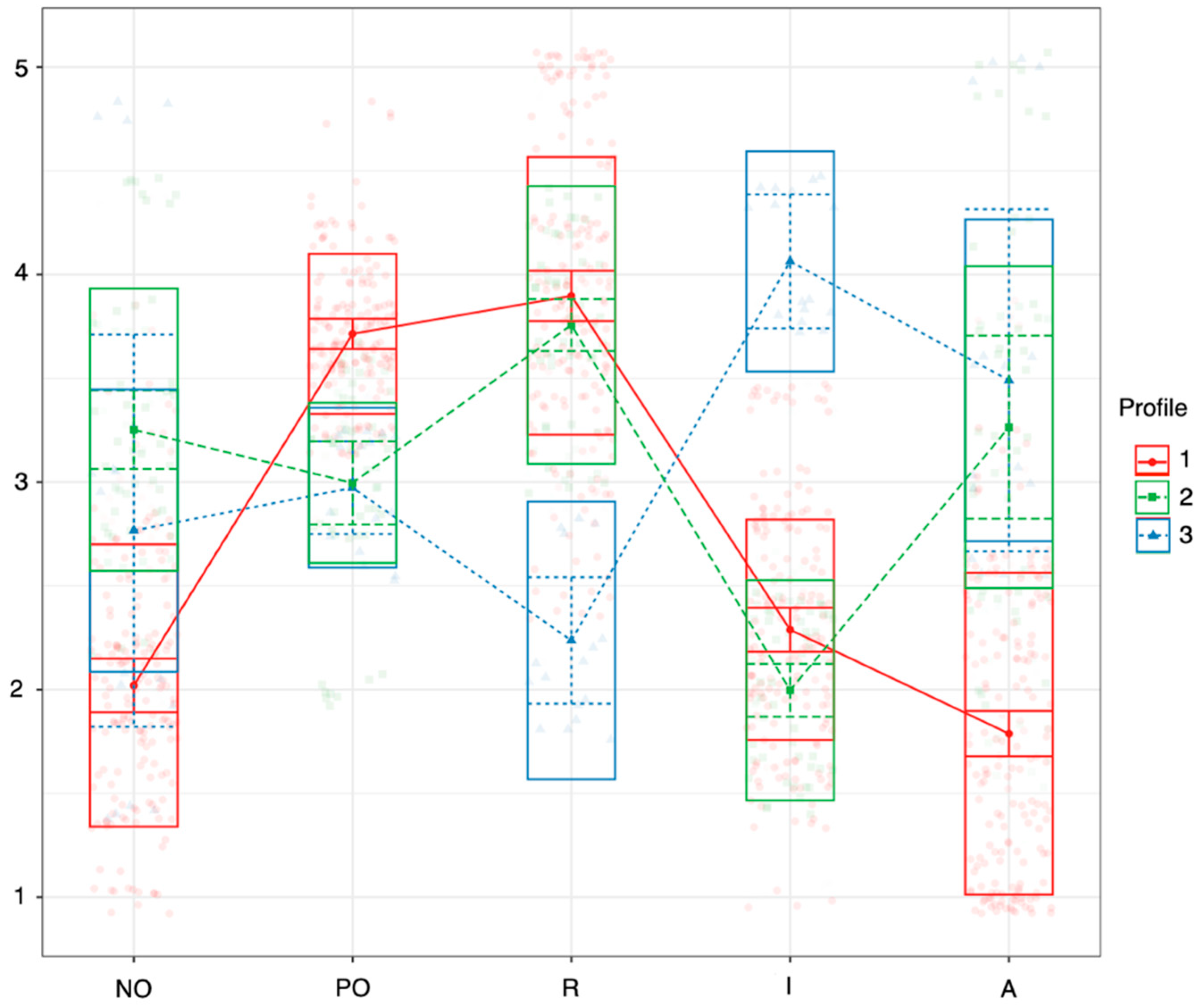

3.3. Latent Profile Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2017). Aggression and violence: Definitions and distinctions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh-Pécsi, A., Tóth, E., & Kasik, L. (2024). Social problem-solving, coping strategies and communication among 5th and 7th graders. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2331592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K. M. J., & Kaukiainen, A. (1992). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 18(2), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E. C., D’Zurilla, T. J., & Sanna, L. J. (2004). Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral and health sciences. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Corcaci, G. (2022). Expression of hostility—Basis of passive aggressive behavior. Correlational study. Eastern-European Journal of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Blais, J. (2007). Responding to bullying: What works. School Psychology International, 28(4), 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C. J. (2003). Social problem-solving skills training for young adolescents [Doctoral dissertation, School of Social and Behavioural Sciences at Swinburne University of Technology]. Available online: https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/48dbad30-ff0c-4f3a-b65a-002c58a3f3b5/1/Christopher%20Joseph%20Duffy%20Thesis.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- D’Zurilla, J. T., Nezu, A. M., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2004). Social problem solving: Theory and assessment. In E. C. Chang, T. J. D’Zurilla, & L. J. Sanna (Eds.), Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training (pp. 202–274). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2002). Social problem-solving inventory–revised (SPSI–R): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Erozkan, A. (2013). The effect of communication skills and interpersonal problem solving skills on social self-efficacy. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 13(2), 739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, F. A., Zulkefli, N. A. M., & Baharom, A. (2023). Aggressive behavior in adolescent: The importance of biopsychosocial predictors among secondary school students. Frontiers in Public Health, 14(11), 992159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauziah, S., Nurjunima, A. D., Tsabitta, K. A., Majid, P. H., & Almuzaffah, M. (2024). The influence of state identity on student aggressivity. Journal of Psychology and Social Sciences, 2(1), 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejes, J. B., Jámbori, S., Kasik, L., Vígh, T., & Gál, Z. (2023). Exploring social problem-solving profiles among Hungarian high school and university students. Heliyon, 9(8), e18913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaumer Erickson, A. S., Noonan, P. M., Monroe, K., & McCall, Z. (2016). Assertiveness questionnaire. University of Kansas, Center for Research on Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Gaumer Erickson, A. S., Soukup, J. H., Noonan, P. M., & McGurn, L. (2018). Assertiveness formative questionnaire. In P. M. Noonan, & A. S. Gaumer Erickson (Eds.), The skills that matter: Teaching interpersonal and intrapersonal competencies in any classroom (pp. 181–182). Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, C. J. (2018). Interpersonal dynamics in personality and personality disorders. European Journal of Personality, 32(5), 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasik, L. (2012). A szociálisprobléma-megoldó és az induktív gondolkodás kapcsolata 8, 12, 15 és 18 évesek körében. Magyar Pedagógia, 112(4), 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kasik, L. (2015). Személyközi problémák és megoldásuk. Gondolat Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Kasik, L., Guti, K., Tóth, E., & Fejes, J. B. (2016). Az elkerülés mint folyamat–Az elkerülés kérdőív bemérése 15 és 18 évesek körében. Magyar Pedagógia, 116(2), 219–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukiainen, A., Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K., Österman, K., Salmivalli, C., Rothberg, S., & Ahlbom, A. (1999). The relationships between social intelligence, empathy, and three types of aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 25, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2005). Social problem solving and the development of aggression. In M. McMurran, & J. McGuire (Eds.), Social problem solving and offending: Evidence, evaluation and evolution (pp. 31–49). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, G. W. (2005). Children’s peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford, J. E., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Giunta, L. D., Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Tapanya, S., & Uribe Tirado, L. M. (2012). Boys’ and girls’ relational and physical aggression in nine countries. Aggressive Behavior, 38(4), 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-O., & Suh, K.-H. (2022). Development and validation of a measure of passive aggression traits: The Passive Aggression Scale (PAS). Behavior Science, 12(8), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthys, W., & Lochman, J. E. (2005). Social problem solving in aggressive children. In M. McMurran, & J. McGuire (Eds.), Social problem solving and offending: Evidence, evaluation and evolution (pp. 51–66). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Millon, T., Millon, C. M., Meagher, S. E., & Ramnath, R. (2004). Personality disorders in modern life (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Vives, F., Camps, E., Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2014). The role of psychological maturity in direct and indirect aggressiveness in Spanish adolescents. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muarifah, A., Mashar, R., Hashim, I. H. M., Rofiah, N. H., & Oktaviani, F. (2022). Aggression in adolescents: The role of mother-child attachment and self-esteem. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neel, R. S., Jenkins, Z. N., & Meadows, N. (1990). Social problem-solving behaviors and aggression in young children: A descriptive observational study. Behavioral Disorders, 16(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, A. M., Wilkins, V. M., & Nezu, C. M. (2004). Social problem solving, stress, and negative affect. In E. C. Chang, T. J. D’Zurilla, & L. J. Sanna (Eds.), Social problem solving (pp. 49–65). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Özgür, G., Yörükoğlu, G., & Arabacı, L. B. (2011). Perception of violence, violence tendency levels and affecting factors in high school students. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, N., Ferreira, P., Simão, A. M. V., Paulino, P., Oliveira, S., & Mora-Merchán, J. A. (2022). Aggressive communication style as predictor of cyberbullying, emotional wellbeing, and personal moral beliefs in adolescence. Psicología Educativa, 28(2), 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipas, M. D., & Jaradat, M. (2010). Assertive communication skills. Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Oeconomica, 12(2), 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzer, J. L., & Beck, A. T. (1996). A cognitive theory of personality disorders. In J. F. Clarkin, & M. F. Lenzenweger (Eds.), Major theories of personality disorder (pp. 36–105). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Romppanen, E., Korhonen, M., Salmelin, R. K., Puura, R., & Luoma, I. (2021). The significance of adolescent social competence for mental health in young adulthood. Mental Helath and Prevention, 21, 200198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzaqyah, F., Silvia, A. R., & Wisma, N. (2020). Aggressive behavior: Comparative study on girls and boys in the middle school. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 513, 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Schanz, C. G., Equit, M., Schäfer, S. K., Käfer, M., Mattheus, H. K., & Michael, T. (2021). Development and psychometric properties of the test of passive aggression. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 579183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauenburg, H., Willenborg, V., Sammet, I., & Ehrenthal, J. C. (2007). Self-reported defence mechanisms as an outcome measure in psychotherapy: A study on the German version of the Defence Style Questionnaire DSQ 40. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 80, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, A. M. H., & Shek, D. T. L. (2005). Relations between social problem solving and indicators of interpersonal and family well-being among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research Series, 71(1–3), 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringer, L. (2019). A pszichiátria tankönyve [Textbook of psychiatry]. Semmelweis Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, S., & Güzel, Ü. (2020). Evaluation of teachers’ perception of effective communication skills according to gender. African Educational Research Journal, 8, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnai, A. (2013). A szociális fejlődés segítése [Supporting social development]. Gondolat Kiadói Kör Kft. [Google Scholar]

| PAS and SPSI–R Factor | 16-Year-Olds (n = 260) | 18-Year-Olds (n = 236) | Levene | t-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p | t | p | |

| Cr | 1.93 (0.75) | 1.78 (0.59) | 10.993 | <0.000 | 1.117 | 0.052 |

| Ig | 1.41 (0.54) | 1.65 (0.58) | 1.046 | 0.307 | −4.692 | <0.000 |

| Sa | 1.70 (0.75) | 1.76 (0.84) | 2.378 | 0.124 | −1.542 | 0.124 |

| PO | 3.49 (0.53) | 3.47 (0.56) | 0.009 | 0.923 | 0.095 | 0.923 |

| NO | 2.22 (0.75) | 2.42 (0.86) | 2.545 | 0.136 | −3.541 | 0.041 |

| R | 3.64 (0.80) | 3.70 (0.83) | 1.999 | 0.158 | −1.414 | 0.158 |

| I | 2.40 (0.59) | 2.43 (0.71) | 6.871 | 0.009 | −2.622 | 0.109 |

| A | 2.35 (0.98) | 2.31 (1.03) | 0.048 | 0.826 | 0.219 | 0.826 |

| PAS and SPSI–R Factor | Cr | Ig | Sa | PO | NO | R | I | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | – | 0.014 | 0.095 | −0.068 | 0.098 | 0.023 | 0.163 * | 0.022 |

| Ig | 0.002 | – | 0.661 ** | −0.139 * | 0.132 | 0.141 * | 0.053 | 0.121 |

| Sa | 0.123 * | 0.446 ** | – | −0.198 * | 0.075 | 0.132 | 0.118 | 0.062 |

| PO | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.059 | – | −0.199 * | 0.484 ** | −0.195 ** | −0.631 ** |

| NO | 0.001 | 0.152 * | 0.034 | –0.439 ** | – | −0.303 * | 0.094 | 0.400 ** |

| R | −0.301 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.122 * | 0.282 ** | −0.100 | – | –0.315 ** | −0.390 ** |

| I | 0.215 ** | –0.259 ** | −0.045 | −0.023 | 0.045 | −0.609 ** | – | 0.195 ** |

| A | 0.181 ** | 0.074 | 0.240 ** | −0.477 ** | 0.536 ** | −0.222 ** | 0.173 ** | – |

| No. of Groups | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | cAIC | SABIC | BLRT | BLRT p | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −1358 | 2748 | 2805 | 2821 | 2754 | 208.56 | 0.01 | 0.834 |

| 3 | −1344 | 2732 | 2810 | 2832 | 2741 | 27.58 | 0.01 | 0.869 |

| 4 | −1323 | 2701 | 2801 | 2829 | 2712 | 42.92 | 0.01 | 0.821 |

| 5 | −1311 | 2690 | 2811 | 2845 | 2703 | 23.11 | 0.01 | 0.807 |

| 6 | −1251 | 2583 | 2725 | 2765 | 2598 | 119.52 | 0.01 | 0.858 |

| No. of Groups | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | cAIC | SABIC | BLRT | BLRT p | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −1262 | 2556 | 2611 | 2627 | 2560 | 180.85 | 0.01 | 0.851 |

| 3 | −1205 | 2454 | 2530 | 2552 | 2461 | 113.46 | 0.01 | 0.894 |

| 4 | −1157 | 2371 | 2468 | 2496 | 2379 | 95.70 | 0.01 | 0.835 |

| 5 | −1148 | 2364 | 2482 | 2516 | 2374 | 18.57 | 0.01 | 0.803 |

| 6 | −1117 | 2313 | 2452 | 2492 | 2325 | 62.67 | 0.01 | 0.886 |

| 16-Year-Olds (n = 260) | 18-Year-Olds (n = 236) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPSI–R Factor | Profile 1 (n = 136, 52.3%) | Profile 2 (n = 124, 47.7%) | Profile 1 (n = 48, 20.3%) | Profile 2 (n = 172, 72.9%) | Profile 3 (n = 16, 6.8%) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| NO | 2.59 a | 0.83 | 2.12 b | 0.70 | 3.25 a | 0.66 | 2.02 b | 0.62 | 2.77 a | 0.33 |

| PO | 3.09 b | 0.41 | 3.85 a | 0.46 | 3.00 b | 0.51 | 3.71 a | 0.35 | 2.97 b | 0.27 |

| R | 3.24 b | 0.85 | 4.00 a | 0.64 | 3.76 a | 0.46 | 3.90 a | 0.74 | 2.24 b | 0.39 |

| I | 2.53 | 0.57 | 2.39 | 0.64 | 2.00 c | 0.37 | 2.28 b | 0.59 | 4.06 a | 0.31 |

| A | 3.21 a | 0.64 | 1.63 b | 0.41 | 3.26 a | 0.94 | 1.79 b | 0.65 | 3.49 a | 0.94 |

| 16-Year-Olds (n = 260) | 18-Year-Olds (n = 236) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAS Factor | Mixed (n = 136, 52.3%) | Positive Rational (n = 124, 47.7%) | Mixed (n = 48, 20.3%) | Positive Rational (n = 172, 72.9%) | Impulsive Avoidant (n = 16, 6.8%) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Cr | 1.95 | 0.67 | 1.89 | 0.75 | 1.57 b | 0.26 | 1.78 b | 0.64 | 2.36 a | 0.90 |

| Ig | 1.50 | 0.53 | 1.42 | 0.55 | 1.82 a | 0.60 | 1.58 b | 0.62 | 1.75 a | 0.48 |

| Sa | 1.89 | 0.85 | 1.77 | 0.74 | 2.01 a | 1.13 | 1.52 b | 0.67 | 1.71 b | 0.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gál, Z.; Nagy, M.T.; Takács, I.K.; Kasik, L. The Relationship Between Social Problem-Solving and Passive-Aggressive Behavior Among Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070140

Gál Z, Nagy MT, Takács IK, Kasik L. The Relationship Between Social Problem-Solving and Passive-Aggressive Behavior Among Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070140

Chicago/Turabian StyleGál, Zita, Márió Tibor Nagy, István Károly Takács, and László Kasik. 2025. "The Relationship Between Social Problem-Solving and Passive-Aggressive Behavior Among Adolescents" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070140

APA StyleGál, Z., Nagy, M. T., Takács, I. K., & Kasik, L. (2025). The Relationship Between Social Problem-Solving and Passive-Aggressive Behavior Among Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070140