Validation of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) in the Italian Context: A Measure for Assessing Alcohol Intake and Binge Drinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ)

1.2. The Present Research

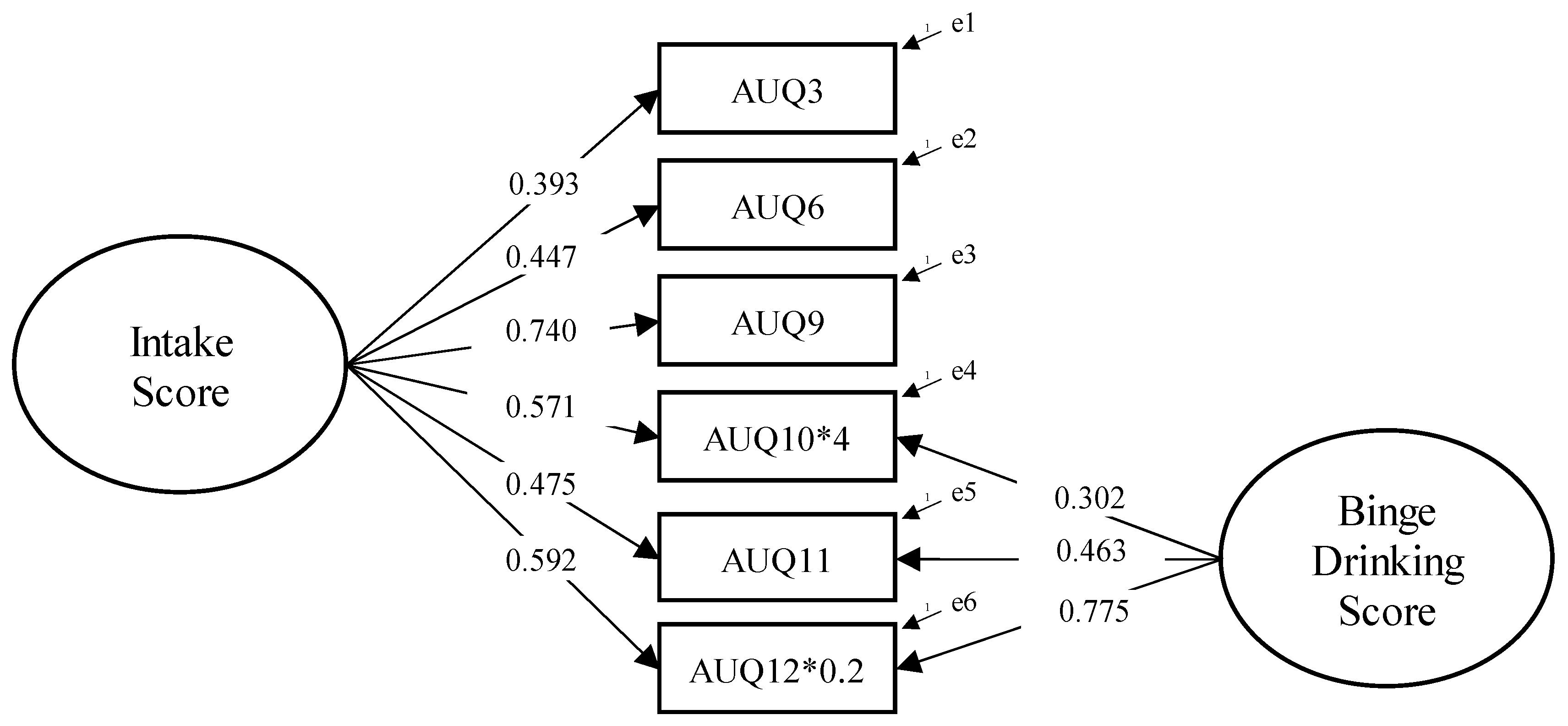

- To test the factor structure of the AUQ by conducting a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), in order to examine the adequacy of a bifactor model reflecting both general alcohol intake and binge drinking patterns.

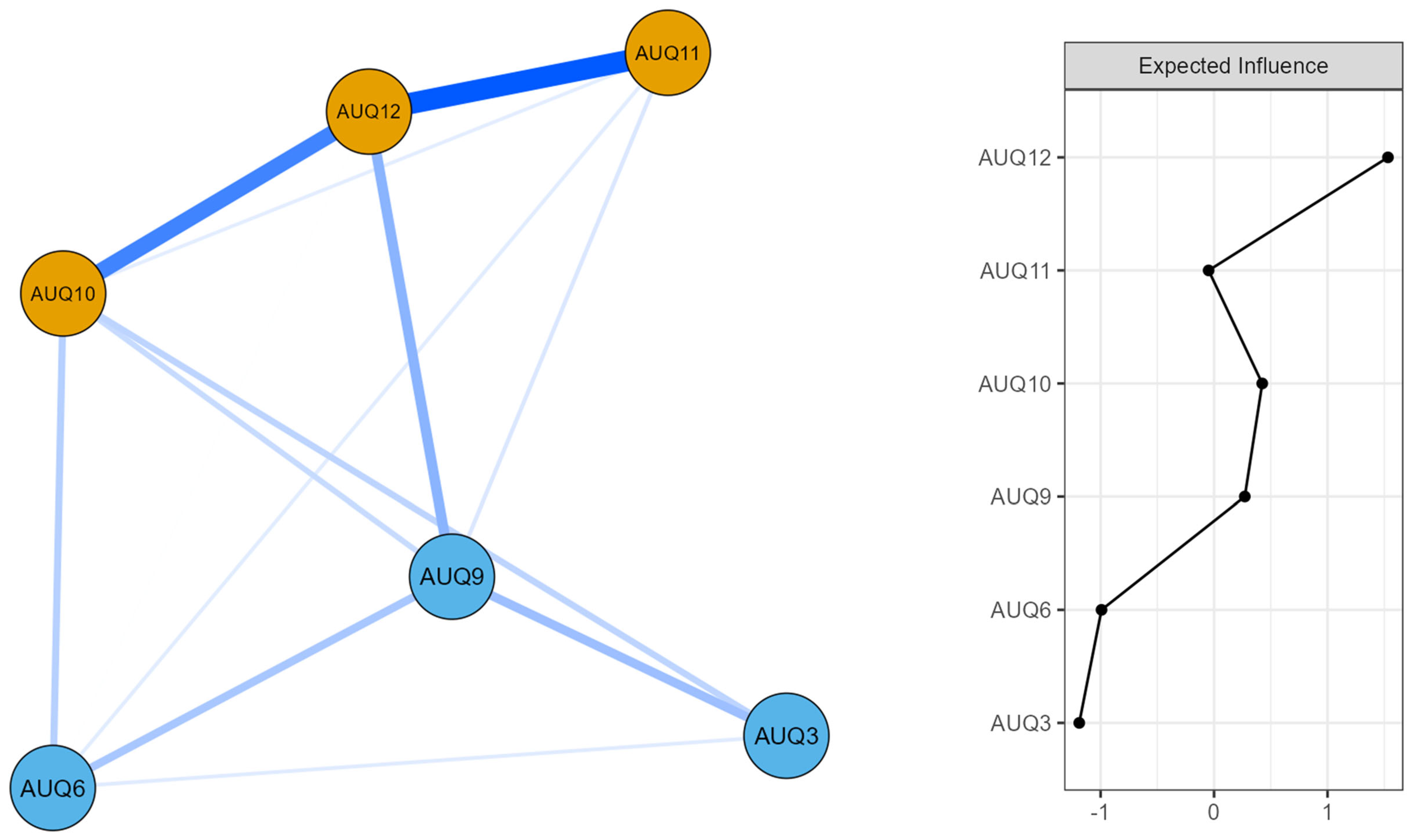

- To further investigate the internal structure of the questionnaire through a network analysis approach, allowing for the exploration of the interconnections between items and the identification of the most central elements in sustaining the structure of alcohol-related behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Ethics

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ)

2.3.2. Binge Eating Scale (BES)

2.3.3. Seven Domains Addiction Scale (7DAS)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Factor Structure and Internal Consistency

3.2. Network Analysis

3.3. Pearson’s Correlation

4. Discussion

4.1. Factor Structure

4.2. Network Structure and Centrality Patterns

4.3. Associations Between the AUQ Indices and Related Psychological Dimensions

5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ)—Italian Version

- Quanti giorni alla settimana bevi vino o qualsiasi prodotto della tipologia dei vini, ad esempio Sherry, Porto, Martini (almeno un bicchiere piccolo)? _______________________________________ Per favore, indica il/i marchio/i che consumi di solito ________________________________________

- Nei giorni in cui bevi vino (o simili), quanti bicchieri (misura da pub) bevi? _______________ se non sei sicuro, stima il numero di bottiglie o parti di una bottiglia ___________________________

- Quanti bicchieri (misura da pub) di vino bevi in una settimana, in totale? ___________________

- Quanti giorni alla settimana bevi birra o sidro (almeno mezza pinta)? ___________________ Per favore, indica il marchio che consumi di solito (ad es. Carlsberg Special, White Lightning ecc.) ______________________________________________________________________________________

- Nei giorni in cui bevi birra/sidro, quante pinte bevi di solito? ____________________________

- Quante pinte di birra/sidro bevi in una settimana, in totale? _____________________________

- Quanti giorni alla settimana bevi superalcolici (Whisky, Vodka, Gin, Rum ecc.—ma non birra o vino)? ______________________________________________________________________________ Per favore, indica il/i marchio/i che consumi di solito (ad es. Smirnoff, Blue Label etc.) ______________________________________________________________________________________

- Nei giorni in cui bevi alcolici, quanti shottini (misura da pub) bevi di solito? ______________ in caso di dubbi, stima il numero di bottiglie o parti di una bottiglia ____________________________

- Quanti bicchieri di superalcolici bevi in una settimana, in totale? __________________________

- Quando bevi, quanto velocemente bevi? (Qui, una bevanda può essere un bicchiere di vino, una pinta di birra o un shottino di liquori, semplici o misti). Per favore clicca sulla la risposta corretta:

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 7+

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 6

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 5

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 4

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 3

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 2

- □

- Bevande all’ora: 1

- □

- 1 bevanda in 2 ore

- □

- 1 bevanda in 3 o più ore

- Quante volte ti sei ubriacato negli ultimi 6 mesi? Per “ubriaco” intendiamo perdita di coordinazione, nausea e/o incapacità di parlare chiaramente _______________________________________

- Qual è la percentuale delle volte che ti ubriachi quando bevi? ____________________________

References

- Addolorato, G., Vassallo, G. A., Antonelli, G., Antonelli, M., Tarli, C., Mirijello, A., Agyei-Nkansah, A., Mentella, M. C., Ferrarese, D., Mora, V., Barbàra, M., Maida, M., Cammà, C., Gasbarrini, A., & Alcohol Related Disease Consortium. (2018). Binge drinking among adolescents is related to the development of alcohol use disorders: Results from a cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aertgeerts, B., Buntinx, F., Ansoms, S., & Fevery, J. (2001). Screening properties of questionnaires and laboratory tests for the detection of alcohol abuse or dependence in a general practice population. British Journal of General Practice, 51(464), 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). text rev.; DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, L. D. S., de Souza, A. P. L., Ferreira, I. M. S., Lima, D. W. D. C., & Pessa, R. P. (2021). Binge eating and alcohol consumption: An integrative review. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babor, T. F., & Higgins-Biddle, J. C. (2001). AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., & Guillemin, F. F. M. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berking, M., Margraf, M., Ebert, D., Wupperman, P., Hofmann, S. G., & Junghanns, K. (2011). Deficits in emotion-regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive–behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betka, S., Pfeifer, G., Garfinkel, S., Prins, H., Bond, R., Sequeira, H., Duka, T., & Critchley, H. (2018). How do self-assessment of alexithymia and sensitivity to bodily sensations relate to alcohol consumption? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(1), 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, J. M., Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2012). Alcohol misuse and violent behavior: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 122(1–2), 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, L. F., Elmer, T., Epskamp, S., Krause, R. W., Schoch, D., Wichers, M., Wigman, J. T. W., & Snippe, E. (2019). What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(8), 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, M., Nagy, G., & Wilhelm, O. (2012). A tutorial on hierarchically structured constructs. Journal of Personality, 80(4), 796–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B. M. (2020). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caretti, V., Gori, A., Craparo, G., Giannini, M., Iraci-Sareri, G., & Schimmenti, A. (2018). A new measure for assessing substance-related and addictive disorders: The addictive behavior questionnaire (ABQ). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(8), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F. F., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J. B., & Paxton, P. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2019). Constructing validity: New developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychological Assessment, 31(12), 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craparo, G., Ardino, V., Gori, A., & Caretti, V. (2014). The relationships between early trauma, dissociation, and alexithymia in alcohol addiction. Psychiatry Investigation, 11(3), 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, D. A., & Room, R. (2000). Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: The Skarpo Conference overview. Journal of Substance Abuse, 12(1–2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology, 14(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bernardo, M., Barciulli, E., Ricca, V., Mannucci, E., Moretti, S., Cabras, P. L., & Rotella, C. M. (1998). Validazione della versione Italiana della binge eating scale in pazienti obesi [Validation of the Italian version of the Binge Eating Scale in obese patients]. Minerva Psichiatrica, 39, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, D. M., Smith, G., Olausson, P., Mitchell, S. H., Leeman, R. F., O’Malley, S. S., & Sher, K. (2010). Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology, 15(2), 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escrivá-Martínez, T., Herrero, R., Molinari, G., Rodríguez-Arias, M., Verdejo-García, A., & Baños, R. M. (2020). Binge eating and binge drinking: A two-way road? An integrative review. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 26(20), 2402–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2016). Drug addiction: Updating actions to habits to compulsions ten years on. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, E. (2021). A user’s guide to network analysis in psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(3), 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg, N. A., Potenza, M. N., Chamberlain, S. R., Berlin, H. A., Menzies, L., Bechara, A., Sahakian, B. J., Robbins, T. W., Bullmore, E. T., & Hollander, E. (2014). Probing compulsive and impulsive behaviors, from animal models to endophenotypes: A narrative review. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(1), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, H. C., Axelrod, S. R., Paliwal, P., Sleeper, J., & Sinha, R. (2008). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2–3), 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foygel, R., & Drton, M. (2010). Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 23. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2010/file/072b030ba126b2f4b2374f342be9ed44-Paper.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2008). Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics, 9(3), 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furr, R. M. (2022). Psychometrics: An introduction (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, A., & Topino, E. (2024). Problematic sexual behaviours, dissociation, and adult attachment: A path analysis model. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 17, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Cacioppo, M., Craparo, G., Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2023a). An integrated approach to addictive behaviors: A study on vulnerability and maintenance factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(3), 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Cacioppo, M., Craparo, G., Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2023b). An addictive disorders severity model: A chained mediation analysis using structural equation modeling. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 41(1), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Craparo, G., Bagnoli, I., Caretti, V., & Schimmenti, A. (2022). A comprehensive model for gambling behaviors: Assessment of the factors that can contribute to the vulnerability and maintenance of gambling disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(1), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormally, J., Black, S., Daston, S., & Rardin, D. (1982). The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors, 7(1), 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A. M., Pilcher, N., & Duka, T. (2020). Deter the emotions: Alexithymia, impulsivity and their relationship to binge drinking. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 12, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. L., Gillaspy, J. A., Jr., & Purc-Stephenson, R. (2009). Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychological Methods, 14(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.3) [computer software]. JASP Team. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel, J. D., Stroud, L. R., & Paronis, C. A. (2003). Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 270–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, P. (2013). Handbook of psychological testing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranzler, H. R. (2023). Overview of alcohol use disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 180(8), 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsche, E., Kuntsche, S., Thrul, J., & Gmel, G. (2017). Binge drinking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health, 32(8), 976–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, F., Baumgartner, E., Baiocco, R., Kotzalidis, G. D., Piacentino, D., Girardi, P., & Angeletti, G. (2016). Alcohol intake and binge drinking among Italian adolescents: The role of drinking motives. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 35(2), 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher-order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, R. K., & Weiss, R. D. (2019). Alcohol use disorder and depressive disorders. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(1), arcr-v40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1978). A questionnaire measure of habitual alcohol use. Psychological Reports, 43(3), 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, D. J., & Carey, K. B. (2007). Association between alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems: An event-level analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(2), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J., Gmel, G. E., Sr., Gmel, G., Hasan, O. S. M., Imtiaz, S., Popova, S., Probst, C., Roerecke, M., Room, R., Samokhvalov, A. V., & Shield, K. D. (2017). The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—An update. Addiction, 112(6), 968–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelle, W., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2009). Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika, 74(1), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T. W., Gillan, C. M., Smith, D. G., de Wit, S., & Ersche, K. D. (2012). Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: Towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L. M., Neighbors, C., & Knee, C. R. (2014). Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(4), 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, A., Chandra, M., Choudhary, M., Dayal, P., & Anand, K. S. (2016). Alcohol-related dementia and neurocognitive impairment: A review study. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction, 5(3), e27976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, I., & Najavits, L. M. (2007). Clinical challenges in the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Current opinion in psychiatry, 20(6), 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, A., Thomasius, R., Sack, P. M., Gemeinhardt, B., & Küstner, U. (2005). Attachment and substance use disorders: A review of the literature and a study in drug dependent adolescents. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shield, K. D., Parry, C., & Rehm, J. (2014). Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 35(2), 155–173. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3908707/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1992). Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods (pp. 41–72). Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stautz, K., & Cooper, A. (2013). Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(4), 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studer, J., Baggio, S., Deline, S., N’Goran, A. A., Henchoz, Y., Mohler-Kuo, M., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2014). Peer pressure and alcohol use in young men: A mediation analysis of drinking motives. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(4), 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhinaraset, M., Wigglesworth, C., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2016). Social and cultural contexts of alcohol use: Influences in a social–ecological framework. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tavares, H., Zilberman, M. L., Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2003). Comparison of craving between pathological gamblers and alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(5), 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorberg, F. A., & Lyvers, M. (2006). Attachment, fear of intimacy and differentiation of self among clients in substance disorder treatment facilities. Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorberg, F. A., & Lyvers, M. (2010). Attachment in relation to affect regulation and interpersonal functioning among substance use disorder in patients. Addiction Research & Theory, 18(4), 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M. M., Bonsaksen, T., Hashemi, N., Kjeken, I., Van Mechelen, W., & Aas, R. W. (2019). Association between alcohol consumption and impaired work performance (presenteeism): A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(7), e029184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topino, E., Griffiths, M. D., & Gori, A. (2024). Attachment and gambling severity behaviors among regular gamblers: A path modeling analysis exploring the role of alexithymia, dissociation, and impulsivity. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22(6), 3760–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topino, E., Griffiths, M. D., & Gori, A. (2025). A compulsive search for love online: A path analysis model of adult anxious attachment, rejection sensitivity, and problematic dating app use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvik, F. A., Rosenström, T. H., Gustavson, K., Ystrom, E., Kendler, K. S., Bramness, J. G., Czajkowski, N., & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. (2019). Explaining the association between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorder: A twin study. Depression and Anxiety, 36(6), 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townshend, J. M., & Duka, T. (2002). Patterns of alcohol drinking in a population of young social drinkers: A comparison of questionnaire and diary measures. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37(2), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuithof, M., ten Have, M., van den Brink, W., Vollebergh, W., & de Graaf, R. (2014). Alcohol consumption and symptoms as predictors for relapse of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 140, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valen, A., Bogstrand, S. T., Vindenes, V., Frost, J., Larsson, M., Holtan, A., & Gjerde, H. (2019). Driver-related risk factors of fatal road traffic crashes associated with alcohol or drug impairment. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 131, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N. D., Wang, G.-J., Fowler, J. S., Tomasi, D., & Telang, F. (2010). Addiction: Beyond dopamine reward circuitry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(37), 15037–15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, N. H., Tull, M. T., Viana, A. G., Anestis, M. D., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance-dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 30, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winograd, R. P., Steinley, D., & Sher, K. (2016). Searching for Mr. Hyde: A five-factor approach to characterizing “types of drunks”. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

| Characteristics | M ± SD | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26.76 ± 8.441 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Females | 206 (54.5%) | ||

| Males | 172 (45.5%) | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 289 (76.5%) | ||

| Cohabiting | 56 (14.8%) | ||

| Married | 29 (7.7%) | ||

| Separated or Divorced | 3 (0.8%) | ||

| Widowed | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Education | |||

| Middle School diploma | 18 (4.8%) | ||

| High School diploma | 192 (50.8%) | ||

| University degree | 98 (25.9%) | ||

| Master’s degree | 53 (14.0%) | ||

| Post-lauream specialization | 17 (4.5%) | ||

| Occupation | |||

| Artisan | 8 (2.1%) | ||

| Employee | 72 (19.0%) | ||

| Entrepreneur | 11 (2.9%) | ||

| Freelance | 13 (3.4%) | ||

| Manager | 4 (1.1%) | ||

| Student | 241 (63.8%) | ||

| Trader | 4 (1.1%) | ||

| Unemployed | 25 (6.6%) | ||

| Item | Response Category | N (%) | Item | Response Category | N (%) | Item | Response Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wine drinking frequency (days/week) | 0 days | 81 (21.4%) | 2. Glasses of wine per drinking day | 0 | 0 (9.9%) | 3. Glasses of wine per week | 0 | 69 (18.3%) |

| 1–2 days | 214 (56.6%) | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 (29.6%) | 0.5–2 | 144 (38.1%) | |||

| 3–4 days | 54 (14.3%) | 1.5–3 | 1.5–3 (48.7%) | 3–5 | 95 (25.1%) | |||

| 5–7 days | 29 (7.7%) | >3 | >3 (11.8%) | 6–10 | 53 (14.0%) | |||

| - | - | - | - | >10 | 15 (4.0%) | |||

| 4. Beer drinking frequency (days/week) | 0 days | 148 (39.2%) | 5. Pints of beer per drinking day | 0 | 131 (34.7%) | 6. Pints of beer per week | 0 | 143 (37.8%) |

| 1–2 days | 191 (50.5%) | 0.5–1 | 160 (42.3%) | 0.5–2 | 162 (42.9%) | |||

| 3–4 days | 29 (7.7%) | 2–3 | 71 (18.8%) | 3–5 | 54 (14.3%) | |||

| 5–7 days | 10 (2.6%) | >3 | 16 (4.2%) | 6–10 | 16 (4.2%) | |||

| - | - | - | - | >10 | 3 (0.8%) | |||

| 7. Spirits drinking frequency (days/week) | 0 days | 139 (36.8%) | 8. Shots of spirits per drinking day | 0 | 162 (42.9%) | 9. Shots of spirits per week | 0 | 134 (35.4%) |

| 1–2 days | 223 (59.0%) | 0.5–1 | 72 (19.0%) | 0.5–2 | 166 (43.9%) | |||

| 3–4 days | 10 (2.6%) | 2–3 | 105 (27.8%) | 3–5 | 56 (14.8%) | |||

| 5–7 days | 6 (1.6%) | >3 | 38 (10.1%) | 6–10 | 20 (5.3%) | |||

| - | - | - | - | >10 | 2 (0.5%) | |||

| 10. Drinking speed | ≥1 drink/2–3 h | 99 (26.2%) | 11. Times drunk in last 6 months | 0 | 172 (45.5%) | 12. % of times drunk when drinking | 0% | 94 (24.9%) |

| 1 drink/h | 127 (33.6%) | 1–2 | 98 (25.9%) | 1–20% | 103 (27.2%) | |||

| 2 drinks/h | 105 (27.8%) | 3–5 | 48 (12.7%) | 21–50% | 106 (28.0%) | |||

| ≥3 drinks/h | 47 (12.4%) | 6–10 | 16 (4.2%) | 51–80% | 62 (16.4%) | |||

| - | - | >10 | 32 (8.5%) | 81–100% | 13 (3.4%) |

| AUQ Indices | Binge Eating Scale | Seven Domains Addiction Scales | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Anxiety | Affect Dysregulation | Somatoform and Psychological Dissociation | Childhood Traumatic Experiences | Impulse Dyscontrol | Compulsive Behaviour and Ritualization | Obsessive Thoughts | |||

| Intake Score | r | 0.300 | 0.161 | 0.186 | 0.228 | 0.090 | 0.262 | 0.180 | 0.136 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.080 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | |

| Binge Drinking Score | r | 0.351 | 0.186 | 0.217 | 0.232 | 0.085 | 0.291 | 0.197 | 0.172 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.099 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Topino, E.; Gori, A. Validation of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) in the Italian Context: A Measure for Assessing Alcohol Intake and Binge Drinking. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070137

Topino E, Gori A. Validation of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) in the Italian Context: A Measure for Assessing Alcohol Intake and Binge Drinking. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070137

Chicago/Turabian StyleTopino, Eleonora, and Alessio Gori. 2025. "Validation of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) in the Italian Context: A Measure for Assessing Alcohol Intake and Binge Drinking" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070137

APA StyleTopino, E., & Gori, A. (2025). Validation of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) in the Italian Context: A Measure for Assessing Alcohol Intake and Binge Drinking. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070137