The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version (PPMI-IT)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Criticisms in the Measurement of Prejudice

1.2. The National Context

1.3. Present Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Materials

The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness (PPMI) Scale

2.5. Translation Back into English

2.5.1. Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding—Italian Version (BIDR-6)

2.5.2. Reliability of the Scale

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

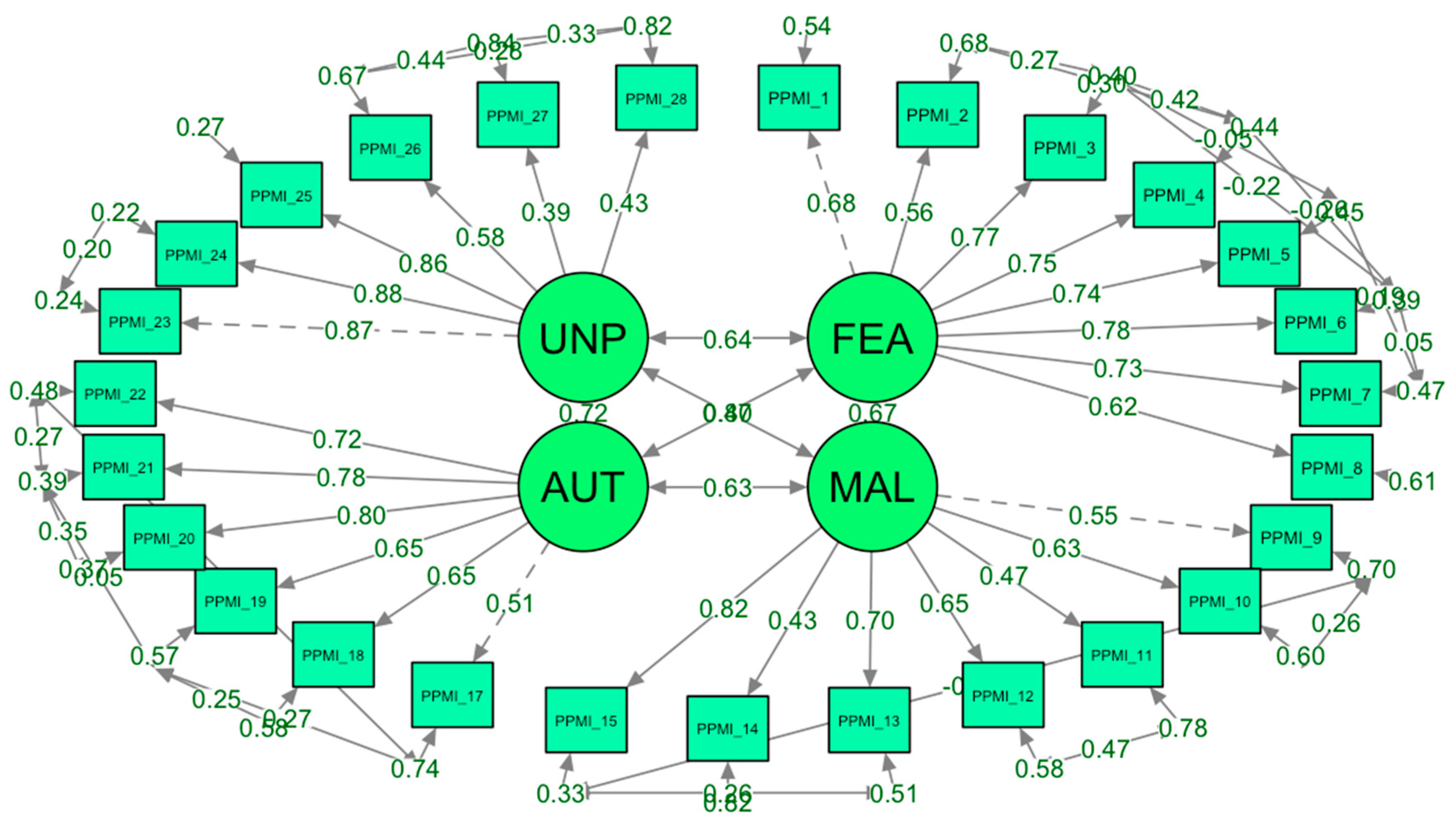

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural and Societal Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. “The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness (PPMI) Scale” Original Version by Kenny et al.

- I would find it hard to talk to someone who has a mental illness

- I would be less likely to become romantically involved with someone if I knew they were mentally ill

- It is best to avoid people who have a mental illness

- I would feel unsafe being around someone who is mentally ill

- I would be just as happy to invite a person with a mental illness into my home as I would anyone else *

- I would feel relaxed if I had to talk to someone who was mentally ill *

- I am not scared of people with a mental illness *

- In general, it is easy to interact with someone who has a mental illness *

- 9.

- People who are mentally ill are avoiding the difficulties of everyday life

- 10.

- People with a mental illness should support themselves and not expect handouts

- 11.

- People who develop a mental illness are genetically inferior to other people

- 12.

- People with a mental illness do not deserve our sympathy

- 13.

- We, as a society, should be spending much more money on helping people with a mental illness *

- 14.

- People who become mentally ill are not failures in life *

- 15.

- We need to support and care for people who become mentally ill *

- 16.

- Under certain circumstances, anyone can experience a mental illness *

- 17.

- People who are mentally ill need to be controlled by any means necessary

- 18.

- Those who have a serious mental illness should not be allowed to have children

- 19.

- People who are mentally ill should be forced to have treatment

- 20.

- People who are mentally ill should be free to make their own decisions *

- 21.

- People who are mentally ill should be allowed to live their lives any way they want *

- 22.

- Society does not have the right to limit the freedom of people with a mental illness *

- 23.

- The behaviour of people with a mental illness is unpredictable

- 24.

- People with a mental illness often do unexpected things

- 25.

- In general, you cannot predict how people with a mental illness will behave

- 26.

- The behaviour of people with a mental illness is just as predictable as that of people who are mentally healthy *

- 27.

- People with a mental illness behave in ways that are foreseeable *

- 28.

- I usually find people with a mental illness to be consistent in their behaviour *

Appendix B. “Scala sul Pregiudizio Verso le Persone con Malattie Mentali” Translation (From English into Italian) by © Bruno & Rizzo, 2024

- Mi verrebbe difficile parlare con qualcuno che ha una malattia mentale

- Sarebbe meno facile essere coinvolto sentimentalmente con qualcuno se sapessi che ha una malattia mentale

- È meglio evitare persone con problemi mentali

- Non mi sentirei al sicuro accanto a qualcuno che ha una malattia mentale

- Sarei felice di invitare a casa mia una persona con una malattia mentale come lo sarei con chiunque altro *

- Mi sentirei rilassato se dovessi parlare con qualcuno che ha una malattia mentale *

- Non ho paura delle persone con malattie mentali *

- In generale, è facile interagire con qualcuno che ha una malattia mentale *

- 9.

- Le persone che sono malate di mente stanno evitando le difficoltà della vita quotidiana

- 10.

- Le persone con malattie mentali dovrebbero aiutarsi da sè senza aspettarsi aiuto

- 11.

- Le persone che sviluppano malattie mentali sono geneticamente inferiori alle altre persone

- 12.

- Le persone con malattia mentale non meritano la nostra simpatia

- 13.

- Noi, come società, dovremmo spendere molti più soldi per aiutare le persone con malattie mentali *

- 14.

- Le persone che si ammalano di mente non sono falliti nella vita *

- 15.

- Dobbiamo sostenere e prenderci cura delle persone che si sviluppano una malattia mentale *

- 16.

- In determinate circostanze, chiunque può sperimentare una malattia mentale *

- 17.

- Le persone che sono malate di mente devono essere controllate con ogni mezzo necessario

- 18.

- Chi ha una grave malattia mentale non dovrebbero essere autorizzato ad avere figli

- 19.

- Le persone con malattia mentale dovrebbero essere costrette a farsi curare

- 20.

- Le persone con malattia mentale dovrebbero essere libere di poter prendere decisioni *

- 21.

- Le persone con malattia mentale dovrebbero poter vivere la loro vita come vogliono *

- 22.

- La società non ha il diritto di limitare la libertà delle persone con malattie mentali *

- 23.

- Il comportamento delle persone con malattie mentali è imprevedibile

- 24.

- Le persone con malattie mentali spesso fanno cose inaspettate

- 25.

- In generale, non è possibile prevedere come si comporteranno le persone con malattie mentali

- 26.

- Il comportamento delle persone con malattie mentali è altrettanto prevedibile di quello delle persone mentalmente sane *

- 27.

- Le persone con malattie mentali si comportano in modi prevedibili *

- 28.

- Di solito trovo che le persone con malattie mentali siano coerenti nel loro comportamento *

Appendix C. “Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale” Back Translation (From Italian into English) by © the Authors

- I would find it hard to talk to someone who has a mental illness

- I would be less likely to become romantically involved with someone who has a mental illness

- It is best to avoid people who have a mental illness

- I would feel unsafe being around someone who has a mental illness

- I would be just as happy to invite a person with a mental illness into my home as I would anyone else

- I would feel relaxed if I had to talk to someone who has a mental illness

- I am not scared of people with a mental illness

- In general, it is easy to interact with someone who has a mental illness

- 9.

- People who have a mental illness are avoiding the difficulties of everyday life

- 10.

- People with a mental Illness should support themselves and not expect a handout

- 11.

- People who develop a mental illness are genetically inferior to other people

- 12.

- People with a mental Illness do not deserve our sympathy

- 13.

- We, as a society, should be spending much more money on helping people with a mental illness

- 14.

- People who are diagnosed with a mental illness are not failures in life

- 15.

- We need to support and care for people who are affected by a mental illness

- 16.

- Under certain circumstances, anyone can experience a mental illness

- 17.

- People who have a mental illness need to be controlled by any means necessary

- 18.

- Those who have a serious mental illness should not be allowed to have children

- 19.

- People who have a mental illness should be forced to have treatment

- 20.

- People who have a mental illness should be free to make their own decisions

- 21.

- People who have a mental illness should be allowed to live their lives any way they want

- 22.

- Society does not have the right to limit the freedom of people with a mental illness

- 23.

- The behavior of people with a mental illness is unpredictable

- 24.

- People with a mental illness often do unexpected things

- 25.

- In general, you cannot predict how people with a mental illness will behave

- 26.

- The behavior of people with a mental illness is just as predictable as that of people who are mentally healthy

- 27.

- People with a mental illness behave in foreseeable ways

- 28.

- I usually find people with a mental illness to be consistent in their behavior

References

- Albarello, F., Moscatelli, S., Menegatti, M., Lucidi, F., Cavicchiolo, E., Manganelli, S., Diotaiuti, P., Chirico, A., & Alivernini, F. (2024). Prejudice towards Immigrants: A Conceptual and Theoretical Overview on Its Social Psychological Determinants. Social Sciences, 13(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. A., Richards, D. A., & Campbell, M. (2005). Nursing attitudes towards acute mental health care: Development of a measurement tool. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(5), 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S. O., & Bishai, D. (2021). Can you repeat the question? Paradata as a lens to understand respondent experience answering cognitively demanding, sensitive questions. PLoS ONE, 16, e0252512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boldrini, T., Buglio, G. L., Lomoriello, A. S., Barsanti, A., Cordova, E., De Salve, F., Gennaro, A., Girardi, P., Göksal, R., Katagiri, N., Kim, S.-W., Lavoie, S., Lingiardi, V., Malvini, L., McGorry, P. D., Miola, A., Nelson, B., Oasi, O., Percudani, M., … Polari, A. (2024). Service users perspectives on psychosis-risk terminology: An Italian study on labeling terms preferences and stigma. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 102, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnington, O., & Rose, D. (2014). Exploring stigmatisation among people diagnosed with either bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder: A critical realist analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Buizza, C., Pioli, R., Ponteri, M., Vittorielli, M., Corradi, A., Minicuci, N., & Rossi, G. (2005). Community attitudes towards mental illness and socio-demographic characteristics: An Italian study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 14, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpiniello, B., Girau, R., & Orrù, M. G. (2007). Mass-media, violence and mental illness. Evidence from some Italian newspapers. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 16, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F., & Rizzo, A. (2024). Tackling mental health disorders, burnout, workplace violence, post-traumatic stress disorders amidst climate change, and new global challenges: The crucial role of emotional management education. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health, 2(1), 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S., Little, K., Meltzer, H., Rose, D., Rhydderch, D., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D. G., & Fick, C. (1993). Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe Crowne social desirability scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M., & Clum, G. A. (2000). Development, reliability, and validity of the beliefs toward mental illness scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 22, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, T., Magnusson, A., Ewertzon, M., & Lützén, K. (2008). Attitudes towards mental illness in Sweden: Adaptation and development of the community attitudes towards mental illness questionnaire. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A., Glozier, N., Leese, M., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Development and responsiveness of a scale to measure clinicians’ attitudes to people with mental illness (medical student version). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, A., Bizumic, B., & Griffiths, K. M. (2018). The Prejudice towards People with Mental Illness (PPMI) scale: Structure and validity. BMC Psychiatry, 18, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalvia, A., Bodini, L., Cristofalo, D., Fin, V., Yanos, P. T., & Bonetto, C. (2025). Assessing the effectiveness and the feasibility of a group-based treatment for self-stigma in people with mental disorders in routine mental health services in North-East Italy: Study protocol for a pragmatic multisite randomized controlled trial. Trials, 26, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S., & Rossi, A. (2019). Assessing mental illness stigma: A complex issue. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matousian, N., & Otto, K. (2023). How to measure mental illness stigma at work: Development and validation of the workplace mental illness stigma scale. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1225838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R., Scott, P. A., Cocoman, A., Chambers, M., Guise, V., Välimäki, M., & Clinton, G. (2012). Is the community attitudes towards the mentally ill scale valid for use in the investigation of European nurses’ attitudes towards the mentally ill? A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingani, L., Forghieri, M., Ferrari, S., Ben-Zeev, D., Artoni, P., Mazzi, F., Palmieri, G., Rigatelli, M., & Corrigan, P. W. (2012). Stigma and discrimination toward mental illness: Translation and validation of the Italian version of the attribution questionnaire-27 (AQ-27-I). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingani, L., Giberti, S., Coriani, S., Ferrari, S., Fierro, L., Mattei, G., Nasi, A. M., Pinelli, G., Wesselmann, E. D., & Galeazzi, G. M. (2021). Translation and validation of an Italian language version of the religious beliefs and mental illness stigma scale (I-RBMIS). Journal of Religion and Health, 60, 3530–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A., Calandi, L., Faranda, M., Rosano, M. G., Carlotta, V., & Vinci, E. (2025). Stigma against mental illness and mental health: The role of social media. Advances in Medicine, Psychology and Public Health, 2(2), 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, A., Calandi, L., Faranda, M., Rosano, M. G., & Vinci, E. (2024). The Link Between Stigmatization, Mental Health, Disability, and Quality of Life. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health, 2, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: A meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyupa, S. (2011). A theoretical framework for back-translation as a quality assessment tool. New Voices in Translation Studies, 7(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Veltro, F., Raimondo, A., Porzio, C., Nugnes, T., & Ciampone, V. (2005). A survey on the prejudice and the stereotypes of mental illness in two communities with or without psychiatric Residential Facilities. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 14(3), 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, R., Archiati, L., Buizza, C., Pasqualetti, P., Rossi, G., & Pioli, R. (2001). Attitude towards psychiatric patients: A pilot study in a northern Italian town. European Psychiatry, 16, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villotti, P., Zaniboni, S., Corbière, M., Guay, S., & Fraccaroli, F. (2018). Reducing perceived stigma: Work integration of people with severe mental disorders in Italian social enterprise. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, C. (2023). Culture of Honor and intentions to seek mental health support: The mediating role of self-construal, reputation and mental health stigma in Italy [Master’s thesis, ISCTE-Instituto Universitario de Lisboa (Portugal)]. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, O. F. (1999). Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A. L., Julious, S. A., Cooper, C. L., & Campbell, M. J. (2016). Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 25, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subscale | Description |

|---|---|

| Fear/Avoidance | The sum of the scores for items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (R), 6 (R), 7 (R), and 8 (R). |

| Malevolence | The sum of the scores for items 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (R), 14 (R), 15 (R), and 16 (R). |

| Authoritarianism | The sum of the scores for items 17, 18, 19, 20 (R), 21 (R), and 22 (R). |

| Unpredictability | The sum of the scores for items 23, 24, 25, 26 (R), 27 (R), and 28 (R). |

| PPMI Scale/Subscale | Cronbach’s Alpha PPMI Original Version (Kenny et al., 2018) | Cronbach’s Alpha PPMI-IT (Present Study) |

|---|---|---|

| Fear/Avoidance | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| Malevolence | 0.73 | 0.80 |

| Authoritarianism | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| Unpredictability | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| PPMI-IT Subscale | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | St. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear/Avoidance | 8 | 70 | 32.09 | 14.216 | 0.367 | −0.487 |

| Malevolence | 8 | 63 | 16.24 | 9.656 | 1.706 | 3.251 |

| Authoritarianism | 6 | 54 | 26.51 | 11.486 | 0.309 | −0.455 |

| Unpredictability | 6 | 54 | 32.86 | 9.911 | 0.143 | 0.205 |

| Fit Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Chi-square (χ2) | 782.54 |

| Degrees of freedom (df) | 296 |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | 0.928 |

| TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index) | 0.914 |

| RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) | 0.060 |

| RMSEA 90% CI | [0.055, 0.065] |

| p-value for RMSEA close fit | 0.0007 |

| SRMR (standardized root-mean-square residual) | 0.060 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruno, F.; Chirico, F.; Khabbache, H.; Rami, Y.; Ait Ali, D.; Cardella, V.; Chayinska, M.; Formica, I.; Rizzo, A. The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version (PPMI-IT). Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070126

Bruno F, Chirico F, Khabbache H, Rami Y, Ait Ali D, Cardella V, Chayinska M, Formica I, Rizzo A. The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version (PPMI-IT). European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070126

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruno, Francesca, Francesco Chirico, Hicham Khabbache, Younes Rami, Driss Ait Ali, Valentina Cardella, Maria Chayinska, Ivan Formica, and Amelia Rizzo. 2025. "The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version (PPMI-IT)" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070126

APA StyleBruno, F., Chirico, F., Khabbache, H., Rami, Y., Ait Ali, D., Cardella, V., Chayinska, M., Formica, I., & Rizzo, A. (2025). The Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version (PPMI-IT). European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070126