Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlational Statistics

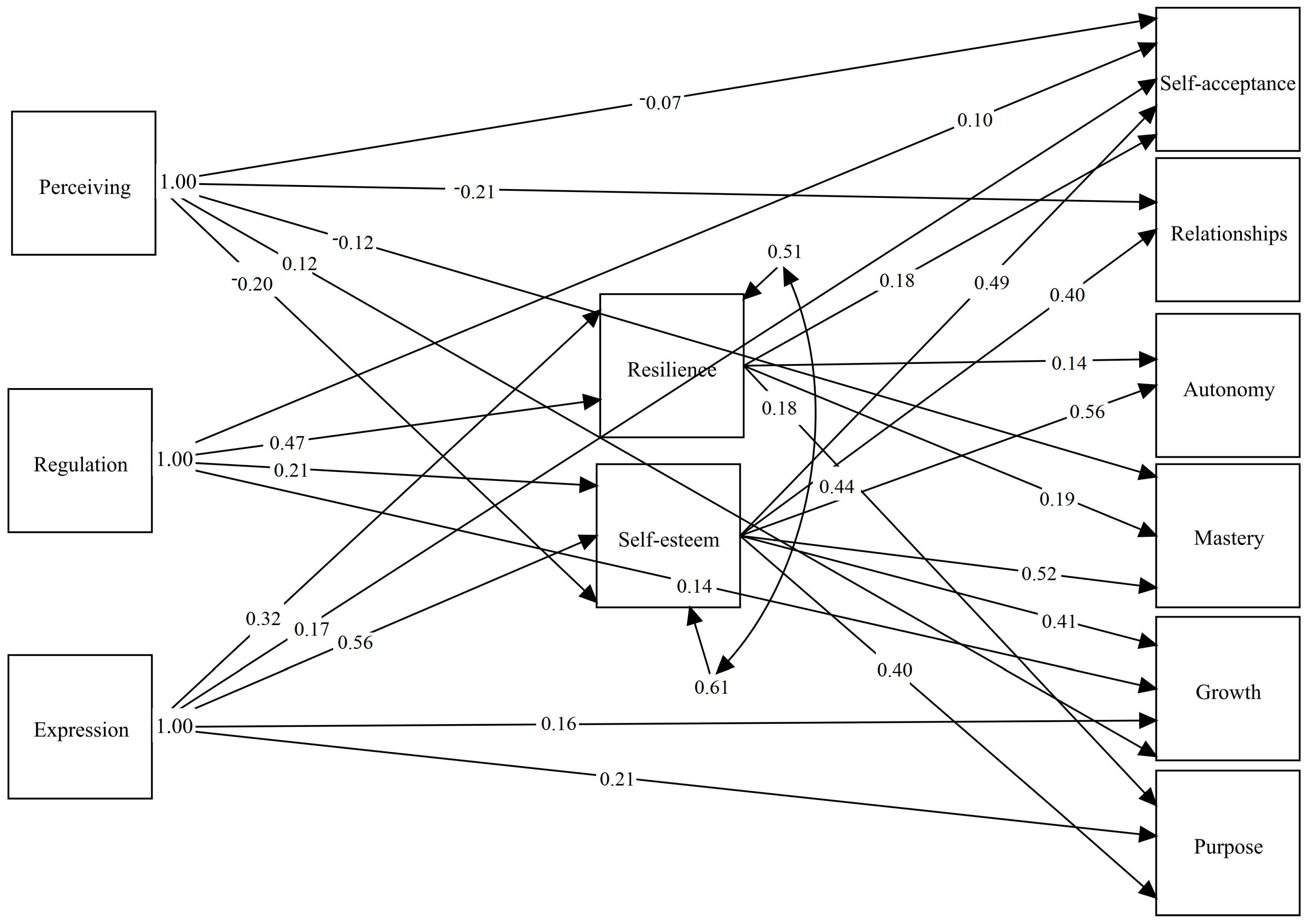

3.2. Mediation Analysis

3.3. Direct Effects

3.4. Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2016). College students as emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2018). Conceptual foundations of emerging adulthood. In Emerging adulthood and higher education (p. 14). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J., & Mitra, D. (2020). Are the features of emerging adulthood developmentally distinctive? A comparison of ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerging Adulthood, 8(5), 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkin, E. A. (2018). Vulnerable populations. In Chronic illness care (pp. 331–341). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Landa, J. M., Pulido-Martos, M., & López-Zafra, E. (2010). Emotional intelligence and personality traits as predictors of psychological well-being in Spanish undergraduates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 38(6), 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Landa, J. M., Pulido-Martos, M., & López-Zafra, E. (2011). Does perceived emotional intelligence and optimism/pessimism predict psychological well-being? Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(3), 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, N., Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2013). The nature of well-being: The roles of hedonic and eudaimonic processes and trait emotional intelligence. The Journal of Psychology, 147(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, M. A., & Salovey, P. (2006). Measuring emotional intelligence with the Mayer-Salovery-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Psicothema, 18(S1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calvo Madurga, A. (2020). Mediación y moderación en modelos lineales. Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, D. R., Mayer, J. D., Bryan, V., Phillips, K. G., & Salovey, P. (2019). Measuring emotional and personal intelligence. In Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (2nd ed., pp. 233–245). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, A. G., McAuley, J. H., & Lee, H. (2022). Advancing the reporting of mechanisms in implementation science: A guideline for reporting mediation analyses (AGReMA). Implementation Research and Practice, 3, 263348952211055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Ospino, G. A., Paba Barbosa, C., Suescún, J., Oviedo, H. C., Herazo, E., & Campo Arias, A. (2017). Validez y dimensionalidad de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en estudiantes universitarios. Pensamiento Psicológico, 15(2), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang Ik Young, C. G.-S. (2016). The relationships between subjective physical education achievements and school life adjustments of elementary school students: Meditation effects of self-esteem and ego-resilience. The Korean Journal of the Elementary Physical Education, 22(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new Resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Rectores. (2023). Noveno estado de la educación 2023. CONARE PEN. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12337/8544 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Duy, B., & Yıldız, M. A. (2019). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrata, P., & Nicomedes, C. J. (2024). Emotional intelligence and perceived social support as predictors of psychological well-being among nurses in hospitals in metro manila: Basis for psychological wellness program. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 49, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M., & Navarro, R. (2022). Parenting styles and self-esteem in adolescent cybervictims and cyberaggressors: Self-esteem as a mediator variable. Children, 9(12), 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, T., Lopez, V., & Klainin-Yobas, P. (2019). Predictors of psychological well-being among higher education students. Psychology, 10(4), 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hashmi, F., Aftab, H., Martins, J. M., Mata, M. N., Qureshi, H. A., Abreu, A., & Mata, P. N. (2021). The role of self-esteem, optimism, deliberative thinking and self-control in shaping the financial behavior and financial well-being of young adults. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0256649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce Fernández, R. (2020). Interdisciplinariedad y transdisciplinariedad en la investigación de Carol Ryff. Naturaleza y Libertad. Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinares, 14(2), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, V., & Meyer, J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: Resilience and support. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 28(3), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. W. Z. (2009). Relation between life satisfaction and self-esteem, social support, social desirability of poor students. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Jarukasemthawee, S., & Pisitsungkagarn, K. (2021). Mindfulness and eudaimonic well-being: The mediating roles of rumination and emotion dysregulation. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 33(6), 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karababa, A. (2022). Understanding the association between parental attachment and loneliness among adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. Current Psychology, 41(10), 6655–6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W., & Jo, M. A. (2022). Impact of peer attachment on children’s subjective well-being: Mediating effects of self-esteem. The Journal of Korean Academy of Physical Therapy Science, 29(3), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Cashin, A. G., Lamb, S. E., Hopewell, S., Vansteelandt, S., VanderWeele, T. J., MacKinnon, D. P., Mansell, G., Collins, G. S., Golub, R. M., McAuley, J. H., Localio, A. R., van Amelsvoort, L., Guallar, E., Rijnhart, J., Goldsmith, K., Fairchild, A. J., Lewis, C. C., Kamper, S. J., … Henschke, N. (2021). A guideline for reporting mediation analyses of randomized trials and observational studies. JAMA, 326(11), 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. E., Kim, E., & Park, S. Y. (2017). Effect of self-esteem, emotional intelligence and psychological well-being on resilience in nursing students. Child Health Nursing Research, 23(3), 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ma, J. H., Yang, B., Wang, S. Z., Yao, Y. J., Wu, C. C., Li, M., & Dong, G. H. (2024). Adverse childhood experiences predict internet gaming disorder in university students: The mediating role of resilience. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 37(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, R., & Malinauskiene, V. (2020). The relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological well-being among male university students: The mediating role of perceived social support and perceived stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Albo, J., Núñez, J. L., Navarro, J. G., & Grijalvo, F. (2007). The rosenberg self-esteem scale: Translation and validation in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence Implications for educators. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. (2023). Indice de Desarrollo Social 2023 Costa Rica. Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, M., Sanson, A. V., Toumbourou, J. W., Hawkins, M. T., Letcher, P., Williams, P., & Olsson, C. (2014). Positive development and resilience in emerging adulthood (J. J. Arnett, Ed.; Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2014). The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Guzmán, M., & Prado Romero, C. (2022). Análisis factorial de la Escala de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff en una muestra de universitarios mexicanos. Revista Digital Internacional de Psicología y Ciencia Social, 8(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera, R., Gonzalez-Yubero, S., Mojsa-Kaja, J., & Szklarczyk-Smolana, K. (2022). Differences in psychological distress, resilience and cognitive emotional regulation strategies in adults during the Coronavirus pandemic: A cross-cultural study of Poland and Spain. Anales de Psicología, 38(2), 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primera Línea. (2024). Composición del Gasto en Universidades Públicas. Composición Del Gasto En Universidades Públicas. [Google Scholar]

- Rammensee, R. A., Morawetz, C., & Basten, U. (2023). Individual differences in emotion regulation: Personal tendency in strategy selection is related to implementation capacity and well-being. Emotion, 23(8), 2331–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rod, M. H., Rod, N. H., Russo, F., Klinker, C. D., Reis, R., & Stronks, K. (2023). Promoting the health of vulnerable populations: Three steps towards a systems-based re-orientation of public health intervention research. Health and Place, 80, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (2016). 2. The measurement of self-esteem. In Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2023a). In pursuit of eudaimonia: Past advances and future directions. In Human flourishing (pp. 9–31). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2023b). Meaning-making in the face of intersecting catastrophes: COVID-19 and the plague of inequality. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 36(2), 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeps, K., Tamarit, A., Postigo-Zegarra, S., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2021). Los efectos a largo plazo de las competencias emocionales y la autoestima en los síntomas internalizantes en la adolescencia. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 26(2), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengyao, Y., Xuefen, L., Jenatabadi, H. S., Samsudin, N., Chunchun, K., & Ishak, Z. (2024). Emotional intelligence impact on academic achievement and psychological well-being among university students: The mediating role of positive psychological characteristics. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, T. E., & Hemenover, S. H. (2006). Is dispositional emotional intelligence synonymous with personality? Self and Identity, 5(2), 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo, Z., Xuyang, D., Xin, Z., Xuebin, C., & Jie, H. (2022). The relationship between postgraduates’ emotional intelligence and well-being: The chain mediating effect of social support and psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 865025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M., & Mitchell, L. L. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(2), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takšić, A. V., Takšić, V., Mohorić, T., & Duran, M. (2009). Emotional skills and competence questionnaire (ESCQ) as a self-report measure of emotional intelligence (Vprašalnik emocionalne inteligentnosti ESCQ kot samoocenjevalna mera emocionalne inteligentnosti). Psihološka Obzorja/Horizons of Psychology, 18(3), 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Álvarez, J. F., González-Bernal, J. J., & López-Liria, R. (2019). Emotion, psychological well-being and their influence on resilience: A study with semi-professional athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(21), 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Moreno, A., Ledesma Amaya, L., & García Cruz, R. (2022). Validación del cuestionario ESCQ-20 en adolescentes mexicanos. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(4), 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, L., Prado-Gascó, V., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2022). Longitudinal analysis of subjective well-being in preadolescents: The role of emotional intelligence, self-esteem and perceived stress. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N., Zhao, Y. M., Yan, W., Li, C., Lu, Q. D., Liu, L., Ni, S. Y., Mei, H., Yuan, K., Shi, L., Li, P., Fan, T. T., Yuan, J. L., Vitiello, M. V., Kosten, T., Kondratiuk, A. L., Sun, H. Q., Tang, X. D., Liu, M. Y., … Lu, L. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: Call for research priority and action. Molecular Psychiatry, 28(1), 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Skew | Kurt | Min | Max | α | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceiving and understanding emotions | 2.89 | 0.57 | −0.36 | 1.10 | 1 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Emotional regulation and management | 2.95 | 0.63 | −0.48 | 0.15 | 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Emotional expression | 2.80 | 0.64 | −0.25 | −0.06 | 1 | 4 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Self-esteem | 28.67 | 6.51 | −0.33 | −0.09 | 10 | 40 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| Resilience | 24.80 | 7.30 | −0.48 | 0.82 | 0 | 40 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Self-acceptance | 4.17 | 1.28 | −0.60 | −0.32 | 1 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Positive relationships | 3.76 | 1.30 | −0.09 | −0.59 | 1 | 6 | 0.69 | 0.71 |

| Autonomy | 4.15 | 1.24 | −0.35 | −0.59 | 1 | 6 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| Environmental mastery | 3.64 | 1.17 | 0.17 | −0.60 | 1 | 6 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| Purpose in life | 4.86 | 1.22 | −1.42 | 1.75 | 1 | 6 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| Personal growth | 4.24 | 1.23 | −0.70 | −0.13 | 1 | 6 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | — | |||||||||

| 2. Resilience | 0.64 *** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Perceiving emotions | 0.19 *** | 0.39 *** | — | |||||||

| 4. Emotional regulation | 0.46 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.41 *** | — | ||||||

| 5. Emotional expression | 0.58 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.59 *** | — | |||||

| 6. Self-acceptance | 0.73 *** | 0.65 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.59 *** | — | ||||

| 7. Positive relationships | 0.36 *** | 0.18 ** | −0.13 * | 0.12 * | 0.18 ** | 0.18 ** | — | |||

| 8. Autonomy | 0.65 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.16 ** | 0.31 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.42 *** | — | ||

| 9. Environmental mastery | 0.61 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.05 | 0.34 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.51 *** | — | |

| 10. Purpose in life | 0.58 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.00 | 0.36 *** | 0.39 *** | — |

| 11. Personal growth | 0.64 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.83 *** | 0.12 * | 0.45 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.74 *** |

| Variables | R2 | Standard Error | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-acceptance | 0.61 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Positive relationships | 0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Autonomy | 0.44 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Environmental mastery | 0.41 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Purpose in life | 0.48 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Personal growth | 0.43 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem | 0.39 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Resilience | 0.49 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| IV | DV | Est | SE | LL 2.5% | UL2.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceiving emotions | Self-acceptance | −0.07 * | 0.03 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| Positive relationships | −0.21 *** | 0.06 | −0.32 | −0.10 | |

| Autonomy | - | - | - | - | |

| Environmental mastery | −0.13 ** | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.03 | |

| Personal growth | 0.12 * | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.23 | |

| Purpose in life | - | - | - | - | |

| Emotional regulation | Self-acceptance | 0.11 * | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| Positive relationships | - | - | - | - | |

| Autonomy | - | - | - | - | |

| Environmental mastery | - | - | - | - | |

| Personal growth | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | |

| Purpose in life | - | - | - | - | |

| Emotional expression | Self-acceptance | 0.17 ** | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.27 |

| Positive relationships | - | - | - | - | |

| Autonomy | - | - | - | - | |

| Environmental mastery | - | - | - | - | |

| Personal growth | 0.16 * | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.28 | |

| Purpose in life | 0.22 *** | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| IV | M | DV | Est | SE | LL 2.5% | UL2.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceiving emotions | Self-esteem | Self-acceptance | −0.10 *** | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.05 |

| Positive relationships | −0.08 ** | 0.03 | −0.13 | −0.03 | ||

| Autonomy | −0.11 *** | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.05 | ||

| Environmental mastery | −0.10 ** | 0.03 | −0.16 | −0.05 | ||

| Personal growth | −0.08 *** | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.04 | ||

| Purpose in life | −0.08 *** | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.04 | ||

| Emotional regulation | Resilience | Self-acceptance | 0.08 ** | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Self-esteem | 0.10 ** | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.16 | ||

| Self-esteem | Positive relationships | 0.08 ** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 | |

| Resilience | Autonomy | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.12 ** | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 | ||

| Resilience | Environmental mastery | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.14 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.11 ** | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.17 | ||

| Self-esteem | Personal growth | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 | |

| Resilience | Purpose in life | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.15 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.08 ** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | ||

| Emotional expression | Resilience | Self-acceptance | 0.06 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Self-esteem | 0.28 *** | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.35 | ||

| Self-esteem | Positive relationships | 0.23 *** | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.31 | |

| Resilience | Autonomy | 0.04 ** | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.32 *** | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.41 | ||

| Resilience | Environmental mastery | 0.06 *** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.29 *** | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.39 | ||

| Self-esteem | Personal growth | 0.23 *** | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.31 | |

| Resilience | Purpose in life | 0.06 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 | |

| Self-esteem | 0.23 *** | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobles Villegas, M.T.; Sanchez-Sanchez, H.; Schoeps, K.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050089

Dobles Villegas MT, Sanchez-Sanchez H, Schoeps K, Montoya-Castilla I. Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050089

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobles Villegas, María Teresa, Hugo Sanchez-Sanchez, Konstanze Schoeps, and Inmaculada Montoya-Castilla. 2025. "Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050089

APA StyleDobles Villegas, M. T., Sanchez-Sanchez, H., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2025). Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050089