Academic Goals and Attitudes Towards Institutional Authority: A Relationship Mediated by Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to the School

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Academic Goals and Attitude Towards Authority

1.2. The Importance of Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to School in Shaping Academic Expectations

- (a)

- Describe the perception of the three types of goal orientations: learning goals (LGs), performance goals (PGs) and reinforcement goals (RGs), as well as their life satisfaction, attitude towards institutional authority and sense of school membership.

- (b)

- Analyse the effect of gender and education level of parents on the scores in negative attitudes towards authority.

- (c)

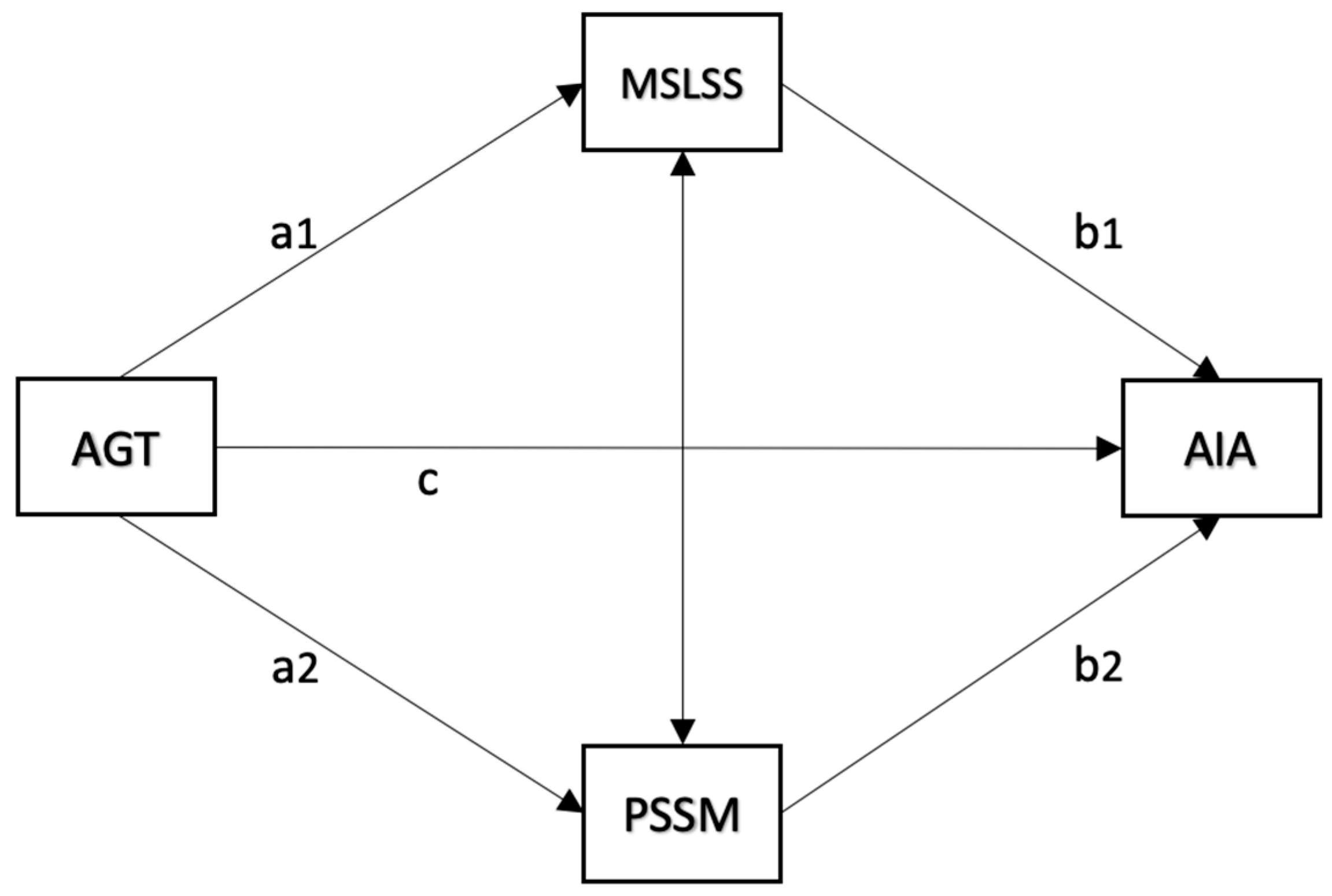

- Analyse the mediating effect of life satisfaction (MSLSS) and sense of school membership (PSSM) in the relationship between goal tendencies (AGT) and negative attitudes (AIA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Specific Objective 1: Descriptive Results

3.2. Specific Objective 2: Score Differences According to Gender and Parents Education Level

3.3. Specific Objective 3: Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Theorical and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albornoz, N., & Cornejo, R. (2017). Discursos docentes sobre el vínculo con sus estudiantes: Tensiones, enfrentamiento y distancia. Estudios Pedagógicos, 43(2), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, J., Guzmán, J., Reyes, F., García, C., Varela, J., & Sirlopú, D. (2016). Satisfacción global con la vida y satisfacción escolar en estudiantes chilenos. Psykhe, 25(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A. M., Milicic, N., & Armijo, I. (2012). Clima social escolar: Una escala de evaluación-Escala de Clima Social Escolar, ECLIS. Universitas Psychologica, 11, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón-Salas, P., Fernández-Martín, F. D., & Arco-Tirado, J. L. (2024). Grit as a predictor of self-regulated learning in students at risk of social exclusion. Curr Psychol, 43, 13365–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, A., Almeida, L., Porto, A., Peralbo, M., & Brenlla, J. (2012). Motivación escolar y rendimiento: Impacto de metas académicas, de estrategias de aprendizaje y autoeficacia. Anales de Psicología, 28(3), 848–859. [Google Scholar]

- Barrantes, K., & Ureña, P. (2015). Bienestar psicológico y bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios costarricenses. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación, 17(1), 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, Y. B., Narváez, M. A., Landazabal, M. S. C., & Vargas, L. E. (2020). Clima organizacional de los procesos de participación comunitaria de una institución educativa. Caso estudio. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 25(11), 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. Bollen, & J. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, R., Mamani, O., Castillo, R., Lingan, S., & Cabrera, I. (2022). Influence of family and academic satisfaction on life satisfaction among Peruvian university students: The mediating role of self-esteem. Frontiers in Education, 7, 867997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C., & Luzón, A. (2019). Respeto docente y convivencia escolar: Significados y estrategias en escuelas chilenas. Psicoperspectivas, 18(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, M. J., Buelga, S., Musitu, G., & Murgui, S. (2010). Violencia escolar entre adolescentes y sus implicaciones en el ajuste psicosocial: Un estudio longitudinal. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 15(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, M. J., Estévez, E., Buelga, S., & Musitu, G. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Actitudes hacia la Autoridad Institucional en adolescentes (AAI-A). Anales de Psicología, 29(2), 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M. J., Musitu, G., & Murgui, S. (2006). Familia y violencia escolar: El rol mediador de la autoestima y la actitud hacia la autoridad institucional. Psicothema, 18(3), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chavarría, M. P., & Barra, E. (2012). Life satisfaction in adolescents: Relationship with self-efficacy and perceived social support. Terapia Psicológica, 32(1), 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M. (2017). El sentido de pertenencia al colegio es un factor clave en el bienestar de los alumnos. Available online: http://www.economiaynegocios.cl/noticias/noticias.asp?id=358589 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Corrales, T., Waterford, M., Goodwin-Smith, I., Wood, L., Yourell, T., & Ho, C. (2016). Childhood adversity, sense of belonging and psychosocial outcomes in emerging adulthood: A test of mediated pathways. Children and Youth Services Review, 63, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, E., & Arias, D. (2015). Validez del Cuestionario de Metas Académicas (CMA) en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 15(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarbajal, A., Esssomba, M. A., & Abenza, B. (2019). El rendimiento académico de los alumnos de la ESO en un contexto vulnerable y multicultural. Educar, 55(1), 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, E., & Emler, N. (2009). Individual differences in attitude to school and social reputation among peers: Implications for behavioral adjustment in educational settings. In J. E. Larson (Ed.), Educational psychology (pp. 342–365). Nova. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, E., Jiménez, T., & Moreno, D. (2011). Cuando las víctimas de violencia escolar se convierten en agresores: “¿Quién va a defenderme?”. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 3, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnique, R., & Huanca, O. (2022). Autoestima y satisfacción familiar como predictores de la satisfacción con la vida en universitarios de la sierra peruana [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Peruana Unión]. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez, J. L., Vera, D., & Trizano, I. (2015). Estudio confirmatorio del cuestionario para evaluar el clima social del centro escolar en Chile. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 32(2), 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- González, C., Navas, L., & Torregrosa, G. (2000). Las metas en situación de aprendizaje: Un análisis en Primaria y Secundaria Obligatoria. In E. Marchena, & C. Alcalde (Eds.), La perspectiva de la educación en el siglo que empieza (vol. II, pp. 744–748). Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- González-Peiteado, M., Pino, M., & Penado, M. (2017). Estudio de la satisfacción percibida por los estudiantes de la UNED con su vida universitaria. RIED: Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 20(1), 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss-Sampson, M. A. (2020). Statistical analysis in JASP (p. 59). University of Greenwich. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, C., Schoeps, K., Montoya-Castilla, I., & Gil-Gómez, J.-A. (2025). Impacto de la inteligencia emocional y del clima escolar sobre el bienestar subjetivo y los síntomas emocionales en la adolescencia. Estudios Sobre Educación, Early Access, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayamizu, T., & Weiner, B. (1991). A test of Dweck’s model of achievenement goal to perceptions of ability. Journal of Experimental Education, 59, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuita, L. F., & Cardona, J. A. (2015). Concepto de calidad de vida en la adolescencia: Una revisión crítica de la literatura. CES Psicología, 8(1), 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal, M., Khabbache, H., & Ait Ali, D. (2024). Dropping out of school: A psychosocial approach. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health, 1(1), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huayta, M., Turpo, J., & Mamani, O. (2022). Predictores de la satisfacción con los estudios en universitarios de salud durante la pandemia COVID-19. Revista Cubana de Enfermería, 20(57), 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.1) [Computer software]. JASP Team.

- Jiao, C., Wang, T., Liu, J., Wu, H., Cui, F., & Peng, X. (2017). Using exponential random graph models to analyze the character of peer relationship networks and their effects on the subjective well-being of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E., Daun, N., & Moronski, K. (2018). Public policy and higher education: Reframing strategies for preparation, access, and college success. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knekta, E., Chatzikyriakidou, K., & McCartney, M. (2020). Measuring university students’ interest in biology: Evaluation of an instrument targeting Hidi and Renninger’s individual interest. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leria, F. J., & Salgado, J. A. (2019). Efecto del clima social escolar en la satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes de primaria y secundaria. Revista de Educación, 43(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Luckner, A., & Pianta, R. (2011). Teacher-student interaction in fifth grade classrooms: Relation with children’s peer behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancila, I., Márquez, M. J., Redón, S., & Angulo, J. F. (2024). Procesos de abandono escolar en España y Chile. La visión de los adolescentes más vulnerables. Revista Complutense de Educación, 35(1), 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C., Domínguez, S., & Fernández, M. (2017). Validación inicial de una Escala Breve de Satisfacción con los Estudios en estudiantes universitarios de Lima. Educación Médica, 18(1), 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchall, A. M., & Jaeger, A. J. (2018). Parental influences on low-income, first-generation students’ motivation on the path to college. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(4), 582–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A., López, A., & Segado, S. (2012). La transición de los jóvenes a la vida adulta. Crisis económica y emancipación tardía. Colección Estudios Sociales, 34, 1–151. [Google Scholar]

- Moreta, R., Gabior, I., & Barrera, L. (2017). El bienestar psicológico y la satisfacción con la vida como predictores del bienestar social en una muestra de universitarios ecuatorianos. Salud & Sociedad, 8(2), 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, E., & Segovia, J. (2014). Evaluación del clima social escolar mediante semilleros de convivencia de los octavos de educación general básica [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de Cuenca (Ecuador)]. [Google Scholar]

- Oyanedel, J. C., Alfaro, J., & Mella, C. (2015). Bienestar subjetivo y calidad de vida en la infancia en Chile. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 13(1), 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, S., & Emler, N. (1985). Delinquent behaviour and attitudes to formal authority. British Journal of Social Psychology, 24(3), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Garcés, C., Espinosa, D., & Padilla, G. (2019). Sense of belonging at school among children and adolescents in Chile: Profiles and paths through decision tree. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 1(81), 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Manteca, F. A., & Rodríguez-Bravo, A. E. (2024). Etiología y metodología de intervención en los procesos de fracaso y abandono escolar. Una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Revista Complutense de Educación, 35(3), 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvalcaba, N., Gallegos, J., & Fuerte, J. M. (2017). Competencias socioemocionales como predictoras de conductas prosociales y clima escolar positivo en adolescentes. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 88(31), 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Salmela, K., & Tuominen, H. (2010). Adolescents life satisfaction during the transition to post-comprehensive education: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6), 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, R., López-Luján, E., Serrano, A., & Giménez-Beut, J. A. (2023). Emotional competences of primary education teachers: A need in school post COVID-19. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(10), 1961–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, A., Sanz, R., Cabanillas, J. L., & López-Lujan, E. (2023). Socio-emotional competencies required by school counsellors to manage disruptive behaviours in secondary schools. Children, 10(2), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. E., Holmes, S. R., Romero, M. E., & Sheridan, S. M. (2022). Evaluating the effects of family-school engagement interventions on parent-teacher relationships: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14(2), 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spady, W. (1971). Dropouts from higher education: Toward an empirical model. Interchange, 2, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffgen, G., Recchia, S., & Viechtbaueer, W. (2013). The link betweeen school climate and violence in school: A meta-analytic review. Aggresion and Violent Behavior, 18, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, A., Cabanach, R., Rodríguez, S., Núñez, J., & González-Pienda, J. (2006). Metas académicas, estrategias cognitivas y estrategias de autorregulación del estudio. Psicothema, 18(2), 165–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veas, A., López-López, J. A., Gilar-Corbi, R., Miñano, P., & Castejón, J. L. (2017). Differences in cognitive, motivational and contextual variables between under-achieving, normally-achieving, and over-achieving Spanish students: A mixed-effects analysis. Psicothema, 29(4), 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-León, J., Caycho, T., & Talledo, K. (2021). Satisfacción académica en estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud antes y durante la pandemia COVID-19. Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas, 20(6), e4257. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, A., Cerda, G., Aragón, E., & Pérez, C. (2021). Rendimiento académico y su relación con las variables socioemocionales en estudiantes chilenos de contextos vulnerables. Educación XX1, 24(2), 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos, B., Carrasco, C., Olavarría, D., Ortiz, S., López, V., Oyarzún, D., Ascorra, P., Ayala, A., Bilbao, A., Morales, M., & Álvarez, J. P. (2016). Victimización de pares y satisfacción con la vida: La influencia del apoyo de profesores y compañeros de la escuela. Psykhe, 25(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yulianti, K., Denessen, E., Droop, M., & Veerman, G. J. (2022). School efforts to promote parental involvement: The contributions of school leaders and teachers. Educational Studies, 48(1), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Centre | ||

| Cabanyal | 19 | 3.725 |

| Isabel de Villena | 47 | 9.216 |

| El Grao | 42 | 8.235 |

| Distrito Marítimo | 160 | 31.373 |

| Baleares | 53 | 10.392 |

| Serpis | 189 | 37.059 |

| Total | 510 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 271 | 53.137 |

| Female | 239 | 46.863 |

| Total | 510 | 100 |

| Course | ||

| Third Secondary | 264 | 51.765 |

| Fourth Secondary | 246 | 48.235 |

| Total | 510 | 100 |

| Father’s Educ. level | ||

| Primary | 42 | 8.23 |

| Secondary | 178 | 34.90 |

| University | 181 | 35.49 |

| Missing | 109 | 21.37 |

| Total | 510 | 100 |

| Mother’s Educ. level | ||

| Primary | 44 | 8.63 |

| Secondary | 183 | 35.88 |

| University | 214 | 41.96 |

| Missing | 69 | 13.53 |

| Total | 510 | 100 |

| Abbreviated Version of the Item | M | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Goals | 3.02 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −0.152 | −0.152 |

| Reinforcement Goals | 2.39 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 4.83 | −0.538 | −0.538 |

| Performance Goals | 4.29 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.509 | 0.509 |

| Overall AGT score | 3.21 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 4.80 | −0.419 | −0.419 |

| Overall MSLSS score | 3.134 | 0.731 | 1.08 | 4.92 | −1.737 | −1.737 |

| Overall PSSM score | 3.586 | 0.589 | 1.89 | 5.00 | 3.112 | 3.112 |

| Negative Attitudes (AIA) | 2.548 | 0.530 | 1.16 | 4.00 | −0.652 | −0.652 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AGT_Learning Goals | — | ||||||

| 2. AGT_Reinforcement Goals | 0.287 *** | — | |||||

| 3. AGT_Performance Goals | 0.507 *** | 0.376 *** | — | ||||

| 4. Overall AGT score | 0.818 *** | 0.693 *** | 0.793 *** | — | |||

| 5. Overall MSLSS score | 0.547 *** | 0.093 * | 0.433 *** | 0.481 *** | — | ||

| 6. Overall AIA score | −0.381 *** | 0.059 | −0.363 *** | −0.309 *** | −0.640 *** | — | |

| 7. Overall PSSM score | 0.408 *** | −0.002 | 0.334 *** | 0.335 *** | 0.644 *** | −0.613 *** | — |

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent | Indicator | Estimate | SE | z | p | Lower | Upper |

| AGT | LG | 1.000 | 0.000 | — | — | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| RG | 0.211 | 0.073 | 2.877 | 0.004 | 0.067 | 0.354 | |

| PG | 0.807 | 0.083 | 9.739 | <0.001 | 0.645 | 0.970 | |

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Effect | Estimate | SE | z | p | Lower | Upper |

| Indirect 1 AGT → PSSM → AIA | −0.118 | 0.022 | −5.468 | <0.001 | −0.161 | −0.076 |

| Indirect 2 AGT → MSLSS → AIA | −0.183 | 0.033 | −5.540 | <0.001 | −0.247 | −0.118 |

| Indirect total effect | −0.301 | 0.039 | −7.695 | <0.001 | −0.378 | −0.224 |

| Total effect | −0.343 | 0.045 | −7.566 | <0.001 | −0.431 | −0.254 |

| Men have a more negative attitude towards authority than women |

| Parents’ level of education shows no difference in negative attitudes towards children’s authority |

| Higher AGT (Academic Goals) = Higher MSLSS (Life Satisfaction) |

| Higher AGT (Academic Goals) = Higher PSSM (Sense of Belonging to School) |

| Higher MSLSS (Life Satisfaction) = Lower AIA (Negative Attitudes Towards Authority) |

| Higher PSSM (Sense of Belonging to the School) = Lower AIA (Negative Attitudes Towards Authority) |

| Higher AGT (Academic Goals) = Higher MSLSS (Life Satisfaction) = Higher PSSM (Sense of Belonging to School) = Lower AIA (Negative Attitudes Towards Authority) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giaquinto, L.; Sanz, R.; García-Grau, P. Academic Goals and Attitudes Towards Institutional Authority: A Relationship Mediated by Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to the School. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050088

Giaquinto L, Sanz R, García-Grau P. Academic Goals and Attitudes Towards Institutional Authority: A Relationship Mediated by Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to the School. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050088

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiaquinto, Laura, Roberto Sanz, and Pau García-Grau. 2025. "Academic Goals and Attitudes Towards Institutional Authority: A Relationship Mediated by Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to the School" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050088

APA StyleGiaquinto, L., Sanz, R., & García-Grau, P. (2025). Academic Goals and Attitudes Towards Institutional Authority: A Relationship Mediated by Life Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging to the School. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050088