Positive Residential Care Integration Scale: Portuguese Adaptation and Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationship with Institutional Caregivers and Other Youth

1.2. Residential Care Institutions

1.3. Measuring Youth Integration in OoH Placements

Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Positive Residential Care Integration (PRCI) Scale

2.2.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, R. Goodman, 1997; Portuguese Version by Pechorro et al., 2011)

2.3. Procedures

Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

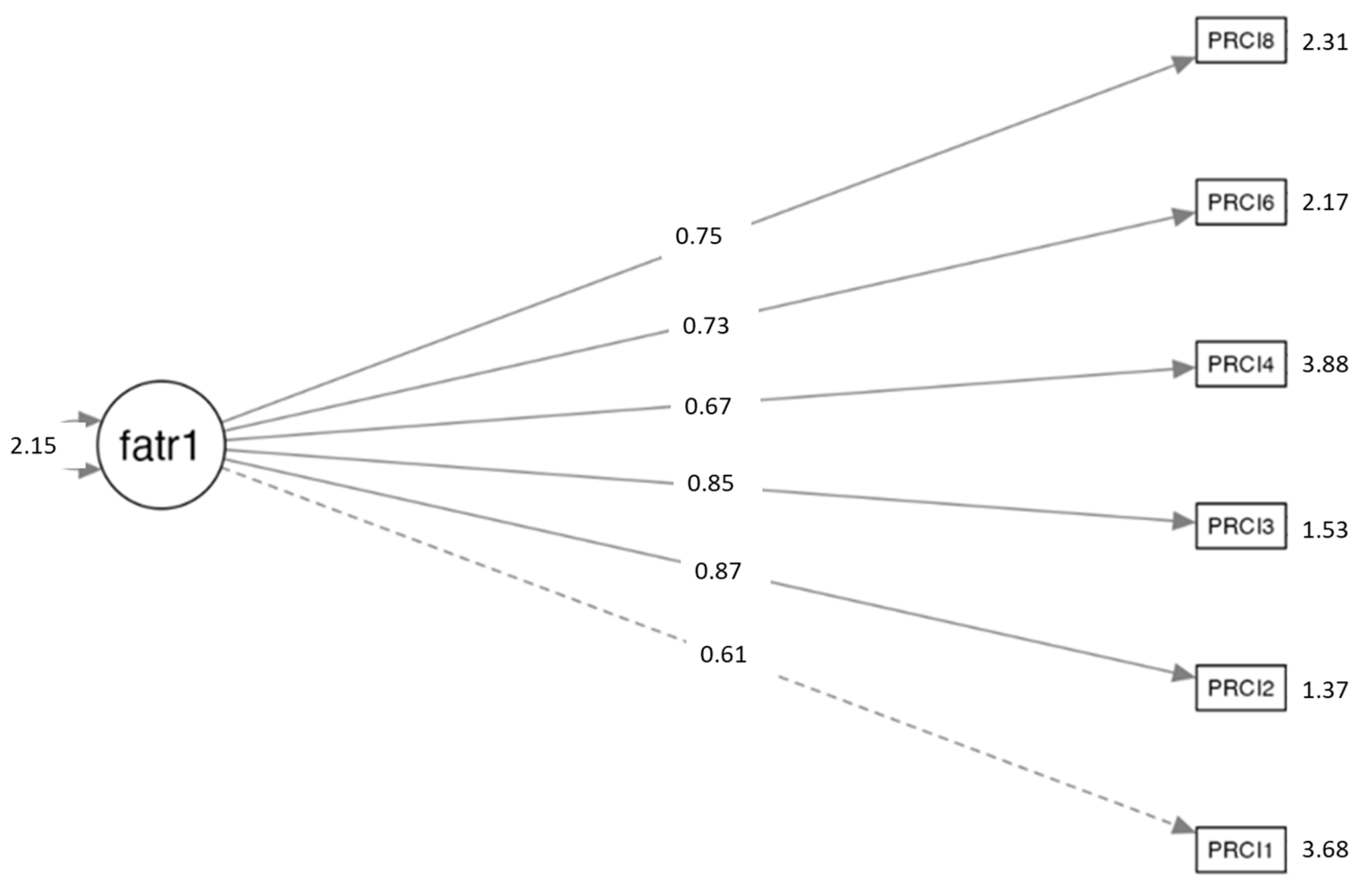

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Measurement Invariance Across Gender

3.4. Discriminant Validity with External Variables and Scale Reliability

4. Discussion

Limitations and Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRCI | Positive Residential Care Integration |

| RCS | Residential Care Settings |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| OoH | Out-of-Home |

| PHI | Positive Home Integration |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Appendix A

| Items | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Quanto é que te sentes integrado/a na instituição? |

| 2 | Em que medida sentes que és tratado/a com gentileza na instituição? |

| 3 | Em que medida sentes que és tratado/a com respeito na instituição? |

| 4 | Em que medida sentes que na instituição te incluem nas decisões? |

| 6 | Como é a tua relação com os auxiliares da instituição? |

| 8 | Como achas que os técnicos da instituição respondem às tuas necessidades? |

References

- Affronti, M., Rittner, B., & Jones, A. M. S. (2015). Functional adaptation to foster care: Foster care alumni speak out. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Vafaie, M. E., Roshani, M., Hassanabadi, H., Masoudian, Z., & Afruz, G. A. (2011). Risk and protective factors for residential foster care adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, A. N., Papp, L. J., Woodbury, M. R., Nelson, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., & Fox, N. A. (2020). The impact of caregiving disruptions of previously institutionalized children on multiple outcomes in late childhood. Child Development, 91(1), 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C. P., Relva, I. C., Costa, M., & Mota, C. P. (2024). Family support, resilience, and life goals of young people in residential care. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, J. (2019). The legacy of the other 23 hours and the future of child and youth care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 36(1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, A. A., & Attar-Schwartz, S. (2020). Staff support and adolescent adjustment difficulties: The moderating role of length of stay in the residential care setting. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar-Schwartz, S. (2011). Maltreatment by staff in residential care facilities: The adolescents’ perspectives. Social Service Review, 85(4), 635–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar-Schwartz, S. (2014). Experiences of sexual victimization by peers among adolescents in residential care settings. Social Service Review, 88(4), 594–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A., Custódio, J. F. M., & Perna, F. P. A. (2013). “Are you happy here?”: The relationship between quality of life and place attachment. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(2), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, I. L. W., Kroes, G., Nijhof, K. S., Delsing, M. J. M. H., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Veerman, J. W. (2012). Measuring group care worker interventions in residential youth care. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(5), 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, O., Holt, S., & Kirwan, G. (2016). Keyworking in residential child care: Lessons from research. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M. J. L. (2013). Sistema nacional de acolhimento de crianças e jovens. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, M. (1989). Foster and residential children’s perceptions of their social environments. The British Journal of Social Work, 19(3), 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, J. F., Bravo, A., Hernández, M., & González, I. (2012). Estándares de calidad en acogimiento residencial—EQUAR [Quality standards in residential care]. Ministerio de Sanidad, Serviços Sociales e igualdade.

- Engel de Abreu, P. M. J., Kumsta, R., & Wealer, C. (2023). Risk and protective factors of mental health in children in residential care: A nationwide study from Luxembourg. Child Abuse & Neglect, 146, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Stuber, S., Nak, J., Veenman, M., & Jorgensen, T. D. (2022). semPlot: Path diagrams and visual analysis of various SEM packages’ output. R Package. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semPlot (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Friesinger, J. G., Haugland, S. H., & Vederhus, J.-K. (2022). The significance of the social and material environment to place attachment and quality of life: Findings from a large population-based health survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20(1), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, M., & Jentschke, S. (2021). SEMLj: Jamovi SEM analysis [jamovi module]. Available online: https://semlj.github.io/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiat, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed). Pearson New International Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R., Merenda, P., & Spielberger, C. (2004). Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2013). A secure base? The adolescent–staff relationship in secure residential youth care. Child & Family Social Work, 18(3), 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J., & Kammerer, N. (2009). Adolescents’ perspectives on placement moves and congregate settings: Complex and cumulative instabilities in out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 29.0). IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto da Segurança Social. (2007). Manual de processos-chave: Lar de infância e juventude. Instituto da Segurança Social. Available online: https://servicosocial.pt/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Lar-de-Inf%C3%A2ncia-e-juventude-Manual-de-Processos-chave.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Instituto da Segurança Social. (2024). CASA 2023—Relatório de caracterização anual da situação de acolhimento das crianças e jovens. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13326/Relat%C3%B3rio_CASA_2023/da8913ce-97e0-4b5d-ae10-bf16c7a88901 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- James, S., & Meezan, W. (2002). Refining the evaluation of treatment foster care. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 83(3), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. S., & LaLiberte, T. (2013). Measuring youth connections: A component of relational permanence for foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(3), 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. S., Rittner, B., & Affronti, M. (2016). Foster parent strategies to support the functional adaptation of foster youth. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(3), 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, N., Leon, S. C., Epstein, R. A., Durkin, E., Helgerson, J., & Lakin-Starr, B. L. (2009). Effect of organizational climate on youth outcomes in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26(3), 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T. D., Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M., & Rosseel, Y. (2025). semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling (Version 0.5-7). R package. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Junot, A., Paquet, Y., & Fenouillet, F. (2018). Place attachment influence on human well-being and general pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 2(2), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Research design in clinical psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, B. H., McBeath, B., Bank, L., Sorenson, P., Waid, J., & Webb, S. J. (2018). Validation of a measure of foster home integration for foster youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(6), 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanctôt, N., Lemieux, A., & Mathys, C. (2016). The value of a safe, connected social climate for adolescent girls in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(3–4), 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law n.º 142/2015. (2015). Law for the protection of children and young people in danger. Diário da república n.º 175, série I de 08-09-2015. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/142-2015-70215246 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Leathers, S. J. (2002). Foster children’s behavioral disturbance and detachment from caregivers and community institutions. Children and Youth Services Review, 24(4), 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leathers, S. J. (2006). Placement disruption and negative placement outcomes among adolescents in long-term foster care: The role of behavior problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(3), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leipoldt, J. D., Harder, A. T., Kayed, N. S., Grietens, H., & Rimehaug, T. (2019). Determinants and outcomes of social climate in therapeutic residential youth care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E. (2015). Psychosocial functioning of adolescents in residential care: The mediator and moderator role of socio-cognitive, relational and individual variables [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL)]. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, E., & Calheiros, M. M. (2015a). Group identification of youth in residential care: Evidences of measurement and dimensionality. Child Indicators Research, 8(2), 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E., & Calheiros, M. M. (2015b). Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of place attachment scale for youth in residential care. Psicothema, 27(1), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E., & Calheiros, M. M. (2017). A dual-factor model of mental health and social support: Evidence with adolescents in residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E., & Calheiros, M. M. (2020). Why place matters in residential care: The mediating role of place attachment in the relation between adolescents’ rights and psychological well-Being. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1717–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E., Calheiros, M. M., & Costa, P. (2016). To be or not to be a rights holder: Direct and indirect effects of perceived rights on psychological adjustment through group identification in care. Children and Youth Services Review, 71, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E., Ferreira, M., Ornelas, S., Silva, C. S., Camilo, C., & Calheiros, M. M. (2023). Youth-caregiver relationship quality in residential youth care: Professionals’ perceptions and experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 41(4), 822–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2021). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações (3rd ed.). ReportNumber. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, E. (2011). Apoyo social percibido en niños y adolescentes en acogimiento residencial. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 11, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, E., & Dávila, L. M. (2008). Social support network and adjustment of minors in residential child care. Psicothema, 20(2), 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. M. (2015). Adolescents in institutional care: Significant adults, resilience and well-being. Child and Youth Care Forum, 44(2), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordinance n.º 450/2023. (2023). Organization, operation and installation of residential homes for children and young people. Diário da repúplica n.º 246, série I de 22-12-2023. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/portaria/450-2023-812826259 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Pechorro, P., Poiares, C., & Vieira, R. (2011). Propriedades psicométricas do questionário de capacidades e de dificuldades na versão portuguesa de auto-resposta [Psychometric properties of the Portuguese self-report version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire]. Journal of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, 16(1), 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, M., Magalhães, E., Calheiros, M. M., & Macdonald, D. (2024). Quality of relationships between residential staff and youth: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 41, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2016). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (6th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauktis, M. E., Fusco, R. A., Cahalane, H., Bennett, I. K., & Reinhart, S. M. (2011). “Try to make it seem like we’re regular kids”: Youth perceptions of restrictiveness in out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(7), 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C. M., Brown, G., & Weber, D. (2010). The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.3) [Computer software]. Available online: https://cran.rproject.org (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Rodrigues, S., Barbosa-Ducharne, M., Del Valle, J. F., & Campos, J. (2019). Psychological adjustment of adolescents in residential care: Comparative analysis of Youth Self-Report/Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C., & De Piccoli, N. (2010). Does place attachment affect social well-being? European Review of Applied Psychology, 60(4), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y., Jorgensen, T. D., De Wilde, L., Oberski, D., Byrnes, J., Vanbrabant, L., Savalei, V., Merkle, E., Hallquist, M., Rhemtulla, M., Katsikatsou, M., Barendse, M., Rockwood, N., Scharf, F., Du, H., Jamil, H., & Classe, F. (2023). lavaan: Latent variable analysis. R package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=lavaan (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Santos, L., Martins, J., Ribeiro da Silva, D., Matos, M., Pinheiro, M. d. R., & Rijo, D. (2023). Emotional climate in residential care scale for youth: Psychometric properties and measurement invariance. Children and Youth Services Review, 148, 106912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2010). Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C. S., Calheiros, M. M., Carvalho, H., & Magalhães, E. (2022). Organizational social context and psychopathology of youth in residential care: The intervening role of youth—Caregiver relationship quality. Applied Psychology, 71(2), 564–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkiss, D. E., Stallard, N., & Thorogood, M. (2013). A systematic literature review of the risk factors associated with children entering public care. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(5), 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Díaz, C., Moreno-Manso, J. M., García-Baamonde, M. E., Guerrero-Molina, M., & Cantillo-Cordero, P. (2022). Behavioral and emotional difficulties and personal wellbeing of adolescents in residential care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J. M., Sinar, E. F., Balzer, W. K., & Smith, P. C. (2002). Issues and strategies for reducing the length of self-report scales. Personnel Psychology, 55(1), 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijbosch, E. L. L., van der Helm, G. H. P., van Brandenburg, M. E. T., Mecking, M., Wissink, I. B., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2014). Children in residential care: Development and validation of a group climate instrument. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(4), 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šiška, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2020). Transition from institutional care to community-based services in 27 EU member states: Final report. European Expert Group on Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF & Eurochild. (2021). Country overviews. Available online: https://eurochild.org/uploads/2022/03/CountryOverviews_Merged.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- van de Vijver, P. J. R. (2016). Test adaptations. In F. T. L. Leong, D. Bartram, F. M. Cheung, K. F. Geisinger, & D. Iliescu (Eds.), The ITC international handbook of testing and assessment (pp. 364–376). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waid, J., Kothari, B. H., Bank, L., & McBeath, B. (2016). Foster care placement change: The role of family dynamics and household composition. Children and Youth Services Review, 68, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waid, J., Kothari, B. H., McBeath, B. M., & Bank, L. (2017). Foster home integration as a temporal indicator of relational well-being. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. R., & Vaske, J. J. (2003). The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. Forest Science, 49(6), 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PRCI Items | M | SD | S | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1: To what extent/how much do you feel included in the institution? | 7.49 | 2.42 | −0.85 | 0.06 |

| Item 2: To what extent do you feel that you are treated with kindness in the institution? | 7.42 | 2.40 | −0.84 | −0.03 |

| Item 3: To what extent do you feel that you are treated with respect in the institution? | 7.50 | 2.32 | −0.79 | −0.10 |

| Item 4: To what extent do you feel that you are involved in decision making in the institution? | 6.65 | 2.64 | −0.47 | −0.64 |

| Item 5: On a scale of 1–10, how good is your relationship with institution’s technicians? | 8.02 | 2.27 | −1.22 | 0.79 |

| Item 6: How well do you get along with the institution’s care workers? | 8.09 | 2.14 | −1.21 | 0.95 |

| Item 7: On a scale of 1–10, how well does institution’s technicians listen to you? | 7.73 | 2.30 | −0.95 | 0.26 |

| Item 8: How well does institution’s technicians respond to your needs? | 7.74 | 2.29 | −0.97 | 0.26 |

| Item 9: When you have a problem, how well does institution’s technicians respond to you? | 7.86 | 2.31 | −1.07 | 0.41 |

| Models/Indices | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | SRMR | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Factor 9-items | 401/27 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.17 | 0.15–0.18 | 0.06 | 18,014 |

| 1-Factor 6-items (without item 5, 7, and 9) | 58.6/9 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | 0.03 | 12,497 |

| Items | β | Alpha if Item Deleted | CITC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item 01 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.57 |

| Item 02 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.79 |

| Item 03 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.77 |

| Item 04 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.64 |

| Item 06 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.68 |

| Item 08 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.71 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SDQ total score | - | 0.74 *** | 0.71 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.63 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.26 *** |

| 2. Emotional problems | - | 0.27 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.22 *** | −0.07 | |

| 3. Behavior problems | - | 0.44 *** | 0.33 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.26 *** | ||

| 4. Hyperactivity/Inattention | - | 0.15 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.16 *** | |||

| 5. Peer problems | - | −0.21 *** | −0.27 *** | ||||

| 6. Prosocial behaviors | - | 0.38 *** | |||||

| 7. PRCI | - | ||||||

| M (SD) | 15.55 | 4.61 | 2.92 | 4.48 | 3.34 | 7.37 | 68.49 |

| (6.24) | (2.42) | (2.03) | (2.38) | (2.04) | (2.31) | (16.63) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simão, A.; Martins, C.; Ratinho, E.; Kothari, B.H.; Nunes, C. Positive Residential Care Integration Scale: Portuguese Adaptation and Validation. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120252

Simão A, Martins C, Ratinho E, Kothari BH, Nunes C. Positive Residential Care Integration Scale: Portuguese Adaptation and Validation. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(12):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120252

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimão, Ana, Cátia Martins, Elias Ratinho, Brianne H. Kothari, and Cristina Nunes. 2025. "Positive Residential Care Integration Scale: Portuguese Adaptation and Validation" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 12: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120252

APA StyleSimão, A., Martins, C., Ratinho, E., Kothari, B. H., & Nunes, C. (2025). Positive Residential Care Integration Scale: Portuguese Adaptation and Validation. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(12), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120252