A 20-Minute Mindful Jazz Intervention Decreased Chronic Pain Patients’ Pain and Anxiety 4 Weeks Later: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

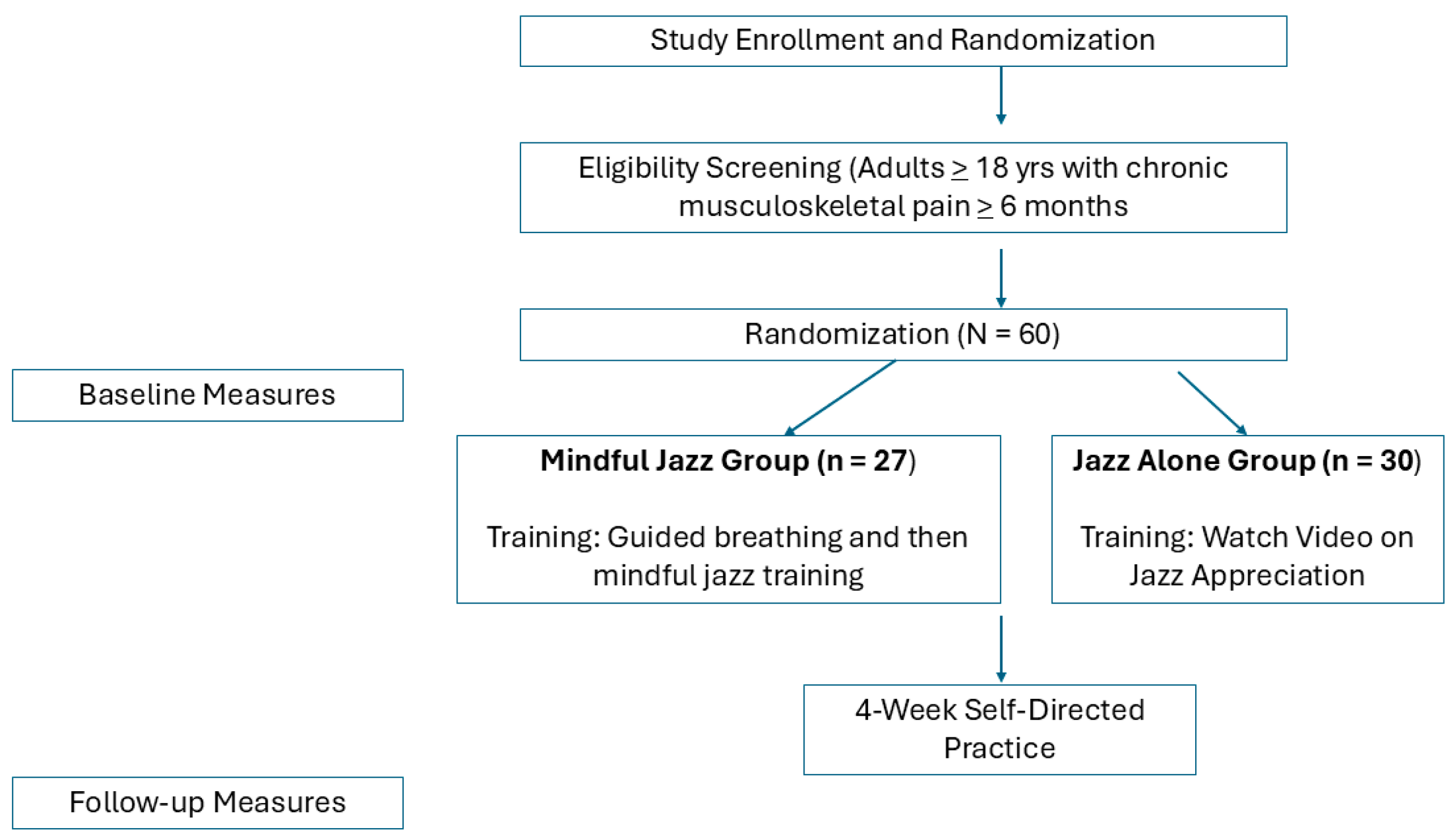

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.4. Sample Size Determination

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Immediate Outcomes

3.3. Follow-Up Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baylan, S., Haig, C., MacDonald, M., Stiles, C., Easto, J., Thomson, M., Cullen, B., Quinn, T. J., Stott, D., Mercer, S. W., Broomfield, N. M., Murray, H., & Evans, J. J. (2020). Measuring the effects of listening for leisure on outcome after stroke (MELLO): A pilot randomized controlled trial of mindful music listening. International Journal of Stroke, 15(2), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesdo, K., Jacobi, F., Hoyer, J., Low, N. C. P., Höfler, M., & Wittchen, H. (2010). Pain associated with specific anxiety and depressive disorders in a nationally representative population sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingham, S. A., Whitehead, A. L., & Julious, S. A. (2013). An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom clinical research network database. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardle, P., Kumar, S., Leach, M., McEvoy, M., & Veziari, Y. (2023). Mindfulness and chronic musculoskeletal pain: An umbrella review. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 16, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W. L.-S., Tang, A. C. Y., Tsang, M. C. M., & Körlin, D. (2023). Effect of music breathing, a program based on mindful breathing and music listening therapy for promoting sense of coherence in young people: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 24(1), 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlan, L., & Heiderscheit, A. (2009). A tool for music preference assessment in critically iii patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support. Music Therapy Perspectives, 27(1), 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B. D., Roy, A., Chen, A. L., Ziadni, M. S., Keane, R. T., You, D. S., Slater, K., Poupore-King, H., Mackey, I., Kao, M., Cook, K. F., Lorig, K., Zhang, D., Hong, J., Tian, L., & Mackey, S. C. (2021). Comparison of a single-session pain management skills intervention with a single-session health education intervention and 8 sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy in adults with chronic low back pain. JAMA Network Open, 4(8), e2113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, E. W., Gerrits, M. M. J. G., Beekman, A. T. F., Dekker, J., Van Marwijk, H. W. J., De Waal, M. W. M., Spinhoven, P., Penninx, B. W. J. H., & Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2014). The association of depression and anxiety with pain: A study from NESDA. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, J. L., Cao, J., Chapin, A., Chen, C., Li, Z., Liu, A., Horst, C., Kaldjian, A., Matyasz, T., Scott, K. W., Bui, A. L., Campbell, M., Duber, H. C., Dunn, A. C., Flaxman, A. D., Fitzmaurice, C., Naghavi, M., Sadat, N., Shieh, P., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). US health care spending by payer and health condition, 1996–2016. JAMA, 323(9), 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, L., Zimmerman, M. B., Hadlandsmyth, K., StMarie, B., Embree, J., Marchman, J., Tripp-Reimer, T., & Rakel, B. (2018). Acceptance and commitment therapy for prevention of chronic postsurgical pain and opioid use in at-risk veterans: A pilot randomized controlled study. The Journal of Pain, 19(10), 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, A. L., & Hernandez-Ruiz, E. (2021). Comparison of music stimuli to support mindfulness meditation. Psychology of Music, 49(3), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, K. J., & Dinsmore, J. A. (2012). Mindful music listening as a potential treatment for depression. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 7(2), 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J. T., Young, J. P., LaMoreaux, L., Werth, J. L., & Poole, M. R. (2001). Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain, 94(2), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frison, L., & Pocock, S. J. (1992). Repeated measures in clinical trials: Analysis using mean summary statistics and its implications for design. Statistics in Medicine, 11(13), 1685–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E. L. (2013). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for addiction, stress, and pain. NASW Press, National Association of Social Workers. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, E. L., Baker, A. K., Larsen, P., Riquino, M. R., Priddy, S. E., Thomas, E., Hanley, A. W., Galbraith, P., Wanner, N., & Nakamura, Y. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of brief mindfulness training and hypnotic suggestion for acute pain relief in the hospital setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(10), 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, A. W., Abell, N., Osborn, D. S., Roehrig, A. D., & Canto, A. I. (2016). Mind the gaps: Are conclusions about mindfulness entirely conclusive? Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(1), 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A. W., Gililland, J., Erickson, J., Pelt, C., Peters, C., Rojas, J., & Garland, E. L. (2021a). Brief preoperative mind–body therapies for total joint arthroplasty patients: A randomized controlled trial. Pain, 162(6), 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A. W., Gililland, J., & Garland, E. L. (2021b). To be mindful of the breath or pain: Comparing two brief preoperative mindfulness techniques for total joint arthroplasty patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(7), 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ruiz, E., & Dvorak, A. L. (2021). Music stimuli for mindfulness practice: A replication study. Journal of Music Therapy, 58(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, E. V., Berbaum, K. S., Faintuch, S., Hatsiopoulou, O., Halsey, N., Li, X., Berbaum, M. L., Laser, E., & Baum, J. (2006). Adjunctive self-hypnotic relaxation for outpatient medical procedures: A prospective randomized trial with women undergoing large core breast biopsy. Pain, 126(1), 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H. (2016). The effects of music on pain: A meta-analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 53(4), 430–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiuk, T. (2016). The Development of a Mindfulness-Based Music Therapy (MBMT) program for women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Healthcare, 4(3), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, J. R., Britton, W. B., Cooper, D. J., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2019). Challenging and adverse meditation experiences. In The oxford handbook of meditation. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2023). ANCOVA versus change score for the analysis of two-wave data. The Journal of Experimental Education, 93(2), 363–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ligero, M., Moral-Munoz, J. A., Salazar, A., & Failde, I. (2023). mHealth Intervention for improving pain, quality of life, and functional disability in patients with chronic pain: Systematic review. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 11, e40844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen. (2014). Nielsen music report. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/news-center/2015/2014-nielsen-music-report/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Piet, J., Würtzen, H., & Zachariae, R. (2012). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbag, E., Felten, R., Sagez, F., Sibilia, J., Devilliers, H., & Arnaud, L. (2019). The world-wide burden of musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic analysis of the World Health Organization Burden of Diseases Database. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 78(6), 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S. M., Dworkin, R. H., Turk, D. C., McDermott, M. P., Eccleston, C., Farrar, J. T., Rowbotham, M. C., Bhagwagar, Z., Burke, L. B., Cowan, P., Ellenberg, S. S., Evans, S. R., Freeman, R. L., Garrison, L. P., Iyengar, S., Jadad, A., Jensen, M. P., Junor, R., Kamp, C., … Wilson, H. D. (2020). Interpretation of chronic pain clinical trial outcomes: IMMPACT recommended considerations. Pain, 161(11), 2446–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidity, M. (2015). What is Jazz? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMgKXbtQwoo (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Teresi, J. A., Yu, X., Stewart, A. L., & Hays, R. D. (2022). Guidelines for designing and evaluating feasibility pilot studies. Medical Care, 60(1), 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, K., Hermann, M., White, J., Speca, M., & Carlson, L. E. (2020). A mixed-method, multi-perspective investigation of barriers to participation in mindfulness-based cancer recovery. Mindfulness, 11(10), 2325–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolovec-Vranic, J., & Natarajan, K. (2016). The use of social media in recruitment for medical research studies: A scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(11), e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A. L., Julious, S. A., Cooper, C. L., & Campbell, M. J. (2016). Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 25(3), 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, Q.-R., Nguyen, M., Roth, S., Broadberry, A., & Mackay, M. H. (2015). Single-item measures for depression and anxiety: Validation of the screening tool for psychological distress in an inpatient cardiology setting. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 14(6), 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S. D., Kim, J., & Hanley, A. (2025). Mindful Jazz and preferred music interventions reduce pain among patients with chronic pain and anxiety: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Cureus, 17(3), e80485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadni, M. S., Gonzalez-Castro, L., Anderson, S., Krishnamurthy, P., & Darnall, B. D. (2021). Efficacy of a single-session “Empowered relief” zoom-delivered group intervention for chronic pain: Randomized controlled trial conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(9), e29672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Demographic | Jazz Alone (n = 27) | Mindful Jazz (n = 30) | Test Statistic | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 44 (11.25) | 40.77 (13.24) | t = 1.02 | 0.31 |

| Sex, n (%) | Χ2 = 0.30 | 0.86 | ||

| Female | 22 (81.48%) | 26 (86.67%) | ||

| Male | 5 (18.52%) | 4 (13.33%) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | X2 = 0.91 | 0.63 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (14.81%) | 4 (13.33%) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 23 (85.19%) | 25 (83.33%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.33%) | ||

| Race, n (%) | X2 = 4.0 | 0.40 | ||

| Asian | 1 (3.70%) | 1 (3.33%) | ||

| Black or African American | 2 (7.41%) | 4 (13.33%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (3.70%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| White | 23 (85.19%) | 24 (80.00%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.33%) | ||

| Education, n (%) | X2 = 10.47 | 0.11 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 10 (37.04%) | 12 (40.0%) | ||

| Completed Graduate or Professional School | 12 (44.44%) | 12 (40.0%) | ||

| Some College/Certificate | 6 (22.22%) | 4 (13.33%) | ||

| Upper Secondary | 1 (3.70%) | 0 | ||

| Vocational/Trade School | 3 (1.11%) | 0 | ||

| Diploma or Equivalent (GED) | 0 | 2 (6.64%) | ||

| Variable | Jazz Alone | Mindful Jazz | Test Statistic | p-Value |

| Average Pain in the Week Prior to Study Enrollment | 7.48 (1.19) | 7.57 (1.43) | t = 0.24 | 0.81 |

| Pain Intensity Immediately Before Intervention | 6.67 (1.54) | 6.17 (1.70) | t = 1.16 | 0.25 |

| Pain Unpleasantness Immediately Before Intervention | 6.78 (1.78) | 6.27 (2.02) | t = 1.01 | 0.32 |

| Anxiety Immediately Before Intervention | 6.59 (1.80) | 5.10 (3.32) | t = 2.14 | 0.04 |

| Variable | Jazz Alone | Mindful Jazz | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity | 5.81 (5.20 to 6.42) | 4.87 (4.29 to 5.45) | 5.04 | 0.029 |

| Pain Unpleasantness | 5.55 (4.92 to 6.18) | 4.27 (3.68 to 4.87) | 8.56 | 0.005 |

| Anxiety | 4.43 (3.74 to 5.13) | 3.11 (2.45 to 3.77) | 7.44 | 0.009 |

| Variable | Jazz Alone | Mindful Jazz | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity | 6.42 (5.88 to 6.95) | 5.43 (4.91 to 5.95) | 4.07 | 0.044 |

| Pain Unpleasantness | 6.11 (5.47 to 6.74) | 5.08 (4.46 to 5.70) | 4.10 | 0.043 |

| Anxiety | 5.95 (5.19 to 6.72) | 4.84 (4.09 to 5.58) | 3.98 | 0.046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, S.D.; Hanley, A. A 20-Minute Mindful Jazz Intervention Decreased Chronic Pain Patients’ Pain and Anxiety 4 Weeks Later: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120239

Young SD, Hanley A. A 20-Minute Mindful Jazz Intervention Decreased Chronic Pain Patients’ Pain and Anxiety 4 Weeks Later: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(12):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120239

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Sean D., and Adam Hanley. 2025. "A 20-Minute Mindful Jazz Intervention Decreased Chronic Pain Patients’ Pain and Anxiety 4 Weeks Later: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 12: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120239

APA StyleYoung, S. D., & Hanley, A. (2025). A 20-Minute Mindful Jazz Intervention Decreased Chronic Pain Patients’ Pain and Anxiety 4 Weeks Later: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(12), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120239