Association Between Decision-Making Styles, Personality Traits, and Socio-Demographic Factors in Women Choosing Voluntary Pregnancy Termination: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

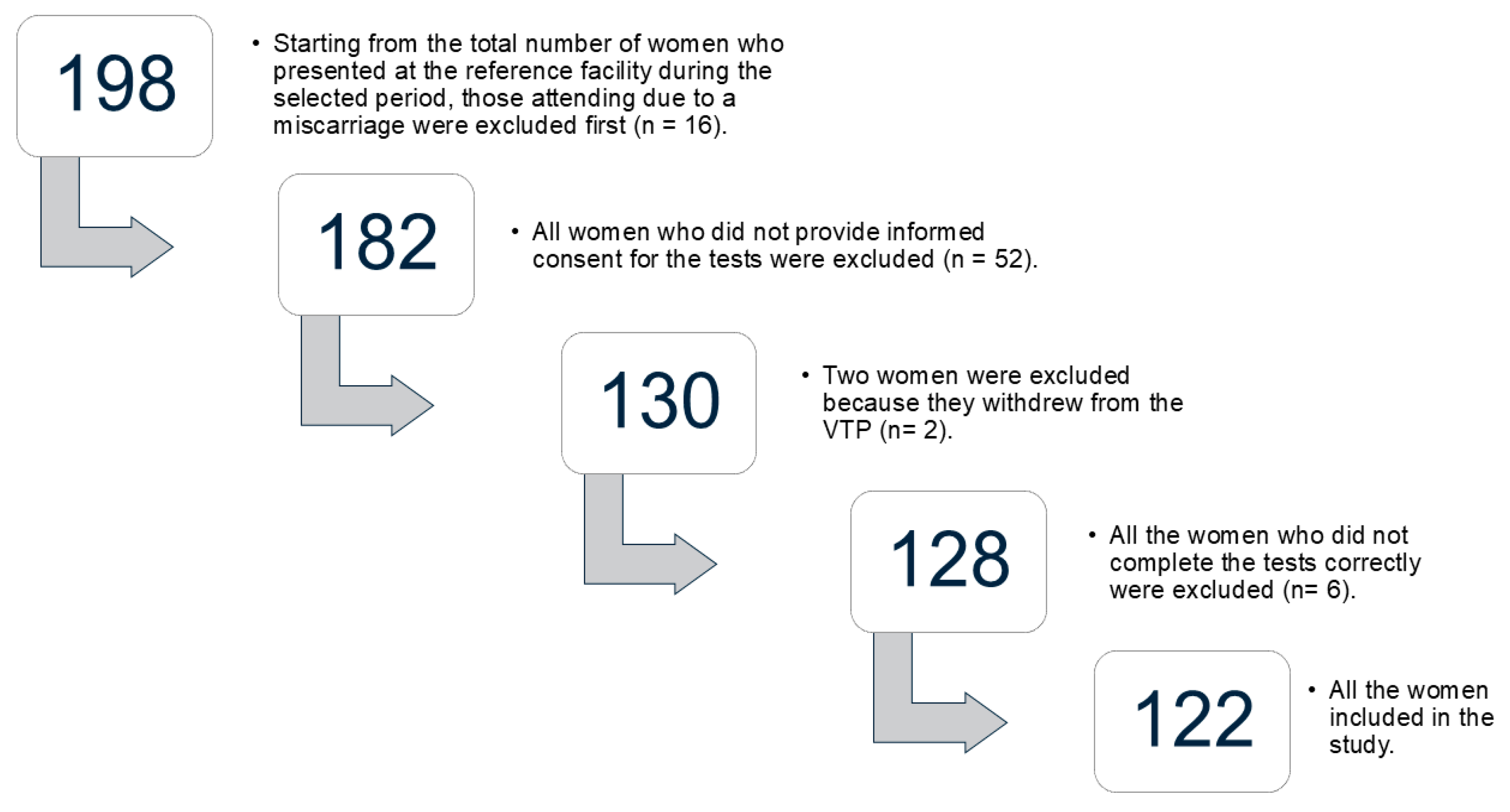

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Assessment of Personality Traits and Decision-Making Style

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

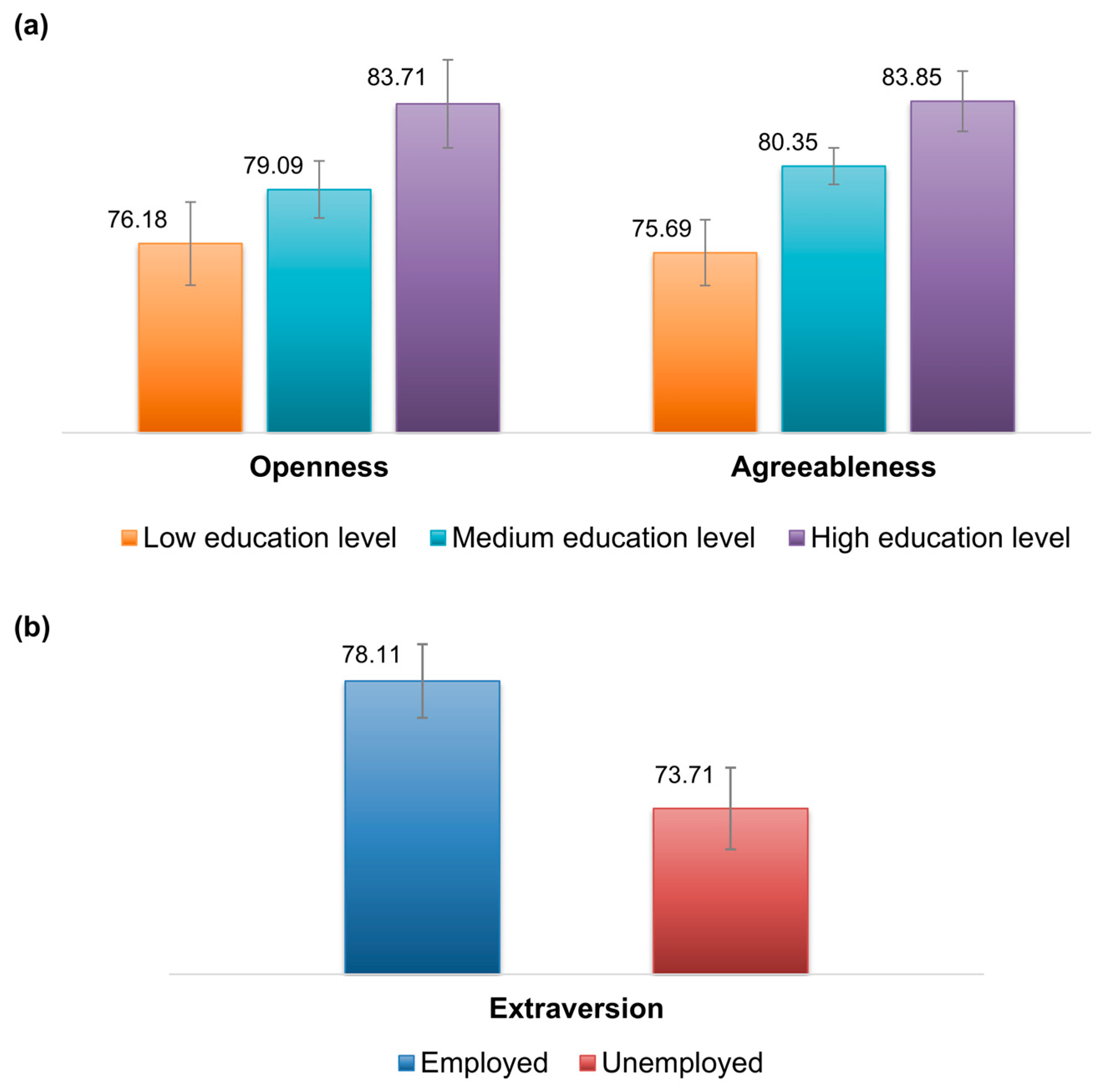

3.1. Associations Between Big Five Questionnaire and Socio-Demographics Characteristics

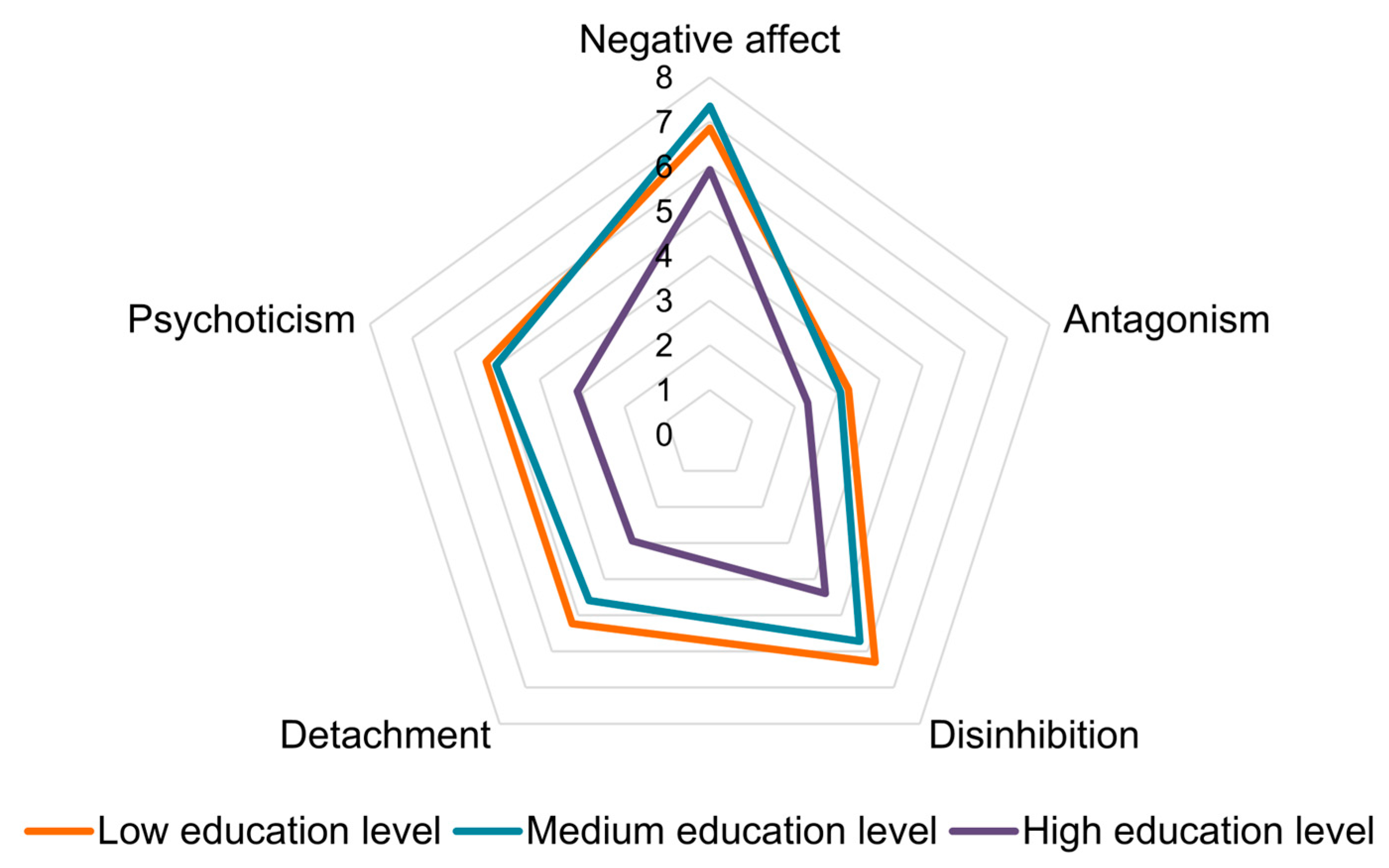

3.2. Associations Between PID-5 Questionnaire and Socio-Demographics Characteristics

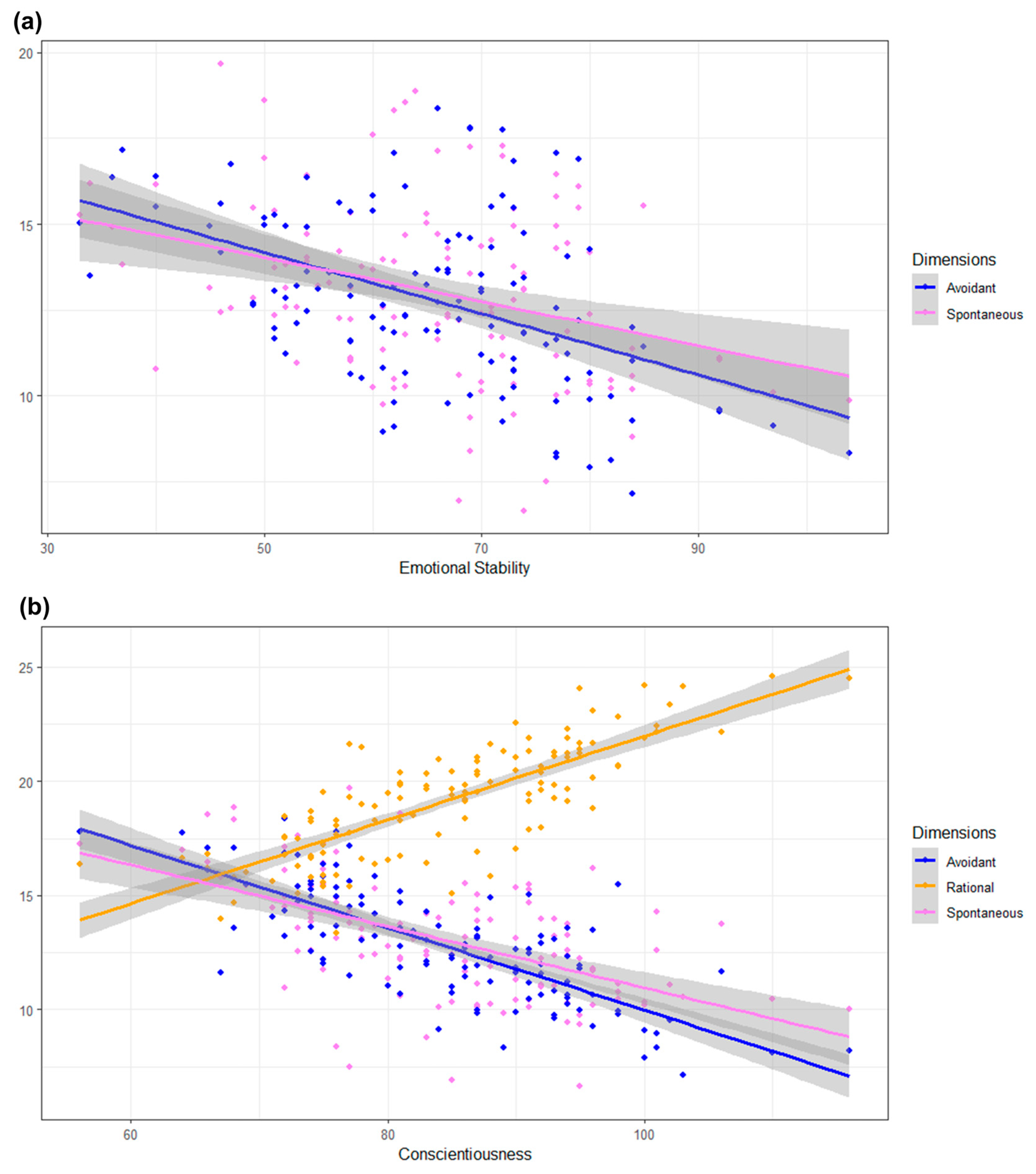

3.3. Associations Between General Decision-Making Style Questionnaire, Socio-Demographic Characteristics, and the Dimensions of the BFQ and PID-5 Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VTP | Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy |

| BFQ | Big Five Questionnaire |

| PID-5-BF | Personality Inventory of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Brief Form |

| PID-5 | Personality Inventory of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| GDMS | General Decision-Making Style |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- Alvergne, A., Jokela, M., & Lummaa, V. (2010). Personality and reproductive success in a high-fertility human population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(26), 11745–11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Gallardo, M., Morales-Asencio, J., Canca-Sánchez, J. C., Barrero-Sojo, S., Perez-Jimenez, C., Morales-Fernández, Á., Luna-Rodriguez, M. E. d., Moya-Suárez, A. B., & Mora-Banderas, A. (2013). Instruments for assessing the risk of falls in acute hospitalized patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmamaw, D. B., Shewarega, E. S., Fentie, E. A., Negash, W. D., Fetene, S. M., Teklu, R. E., Alemu, T. G., Eshetu, H. B., Belay, D. G., & Aragaw, F. M. (2024). Married Women Decision-Making Autonomy on Contraceptive Use in East Africa: A Multilevel Analysis of Recent Demographic and Health Survey. SAGE Open, 14(1), 21582440241236567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayamolowo, L. B., Ayamolowo, S. J., Adelakun, D. O., & Adesoji, B. A. (2024). Factors influencing unintended pregnancy and abortion among unmarried young people in Nigeria: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir Dev, M., & Bayram Arlı, N. (2025). The Role of Personality Traits and Decision-Making Styles in Career Decision-Making Difficulties. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N. (2017). Decision-making styles and personality traits. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/87537611/Decision_Making_Styles_and_Personality_Traits (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Biggs, M. A., Gould, H., & Foster, D. G. (2013). Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Women’s Health, 13(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M., van Ditzhuijzen, J., Boeije, H., & van Nijnatten, C. (2019). Understanding decision-making and decision difficulty in women with an unintended pregnancy in the Netherlands. Qualitative Health Research, 29(8), 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broen, A. N., Moum, T., Bødtker, A. S., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2005). The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: A longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Medicine, 3(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K., & Hosmer, D. W. (2008). Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code for Biology and Medicine, 3(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Perugini, M. (1993). The “big five questionnaire”: A new questionnaire to assess the five factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 15(3), 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Monge, F. J., Marín-Morales, D., Peñacoba-Puente, C., Carretero-Abellán, I., & Moreno-Moure, M. A. (2012). Influencia de las estrategias de afrontamiento en las preocupaciones específicas del embarazo. Anales de Psicología / Annals of Psychology, 28(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzarelli, C. (1993). Personality and self-efficacy as predictors of coping with abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(6), 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, R., Strough, J., Parker, A. M., & de Bruin, W. B. (2015). Variations in decision-making profiles by age and gender: A cluster-analytic approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, J. H., Spengler, M., Frintrup, A., & Mussel, P. (2021). Personality Development in Emerging Adulthood—How the Perception of Life Events and Mindset Affect Personality Trait Change. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 671421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, K. A., Vogt, R. L., Zheng, A., Gillath, O., Deboeck, P. R., Fraley, R. C., & Briley, D. A. (2024). Life events sometimes alter the trajectory of personality development: Effect sizes for 25 life events estimated using a large, frequently assessed sample. Journal of Personality, 92(1), 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Othman, R., El Othman, R., Hallit, R., Obeid, S., & Hallit, S. (2020). Personality traits, emotional intelligence and decision-making styles in Lebanese universities medical students. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EpiCentro. (2022). Voluntary termination of pregnancy in Italy in 2020. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/voluntary-termination-pregnancy/epidemiology (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Fergusson, D. M., John Horwood, L., & Ridder, E. M. (2006). Abortion in young women and subsequent mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M., Fernandes, B., Duarte, J., & Chaves, C. (2015). Attitudes of Women Regarding the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Ribera, L., Pérez, G., Salvador, J., & Borrell, C. (2008). Socioeconomic inequalities in unintended pregnancy and abortion decision. Journal of Urban Health, 85(1), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A., Krueger, R. F., Markon, K. E., Borroni, S., & Maffei, C. (2013). Reliability and validity of the personality inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5): Predicting DSM-IV personality disorders and psychopathy in community-dwelling Italian adults. Assessment, 20(6), 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossati, A., Somma, A., Borroni, S., Markon, K. E., & Krueger, R. F. (2017). The personality inventory for DSM-5 brief form: Evidence for reliability and construct validity in a sample of community-dwelling Italian adolescents. Assessment, 24(5), 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2024). The big-five personality factors, cognitive ability, health, and social-demographic indicators as independent predictors of self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetti, E., Fabbri, M., Bensi, L., & Tonetti, L. (2008). A contribution to the Italian validation of the general decision-making style inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(4), 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GU No. 109, 12-05-2017. (2017). D.P.C.M., 3 March 2017. (2017, March 3). Identification of surveillance systems and mortality, cancer, and other disease registries (17A03142). GU No. 109, 12-05-2017. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2017-05-12&atto.codiceRedazionale=17A03142&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Holtmann, A. C., Menze, L., & Solga, H. (2021). Intergenerational transmission of educational attainment: How important are children’s personality characteristics? American Behavioral Scientist, 65(11), 1531–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B. T., Costello, C. K., Pearman, J., Razavi, P., Bedford-Petersen, C., Ludwig, R. M., & Srivastava, S. (2021). The big five across socioeconomic status: Measurement invariance, relationships, and age trends. Collabra: Psychology, 7(1), 24431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason, P. K., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Baldacchino, J. (2017). Before and after: Personality pathology, childhood conditions, and life history outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, R. N., Kaburu, E. W., Andrew-Bassey, U., Abdiwali, S. A., Nahayo, B., Samuel, N., & Akinyemi, J. O. (2024). Factors associated with pregnancy termination in six sub-Saharan African countries. PLOS Global Public Health, 4(5), e0002280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, T. (2016). Personality change from life experiences: Moderation effect of attachment security. Japanese Psychological Research, 58(2), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. n. 194/1978. (1978). L. n. 194/1978. (1978, May 22). Law 22nd May 1978, n. 194. (1978). Rules for the social protection of maternity and on the voluntary termination of pregnancy. GU n.140 del 22-05-1978. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1978/05/22/078U0194/sg (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- L. n. 405/1975. (1975). L. n. 405/1975. (1975, July 29). Law 29th July 1975, n. 405. (1975). Establishment of Family Counseling Centers. On the 29th of July 1975, law 405 established family planning counselling facilities for the administration of necessary means to allow freely chosen decisions to be made regarding responsible procreation, including for minors. GU n.227 del 27-08-1975. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1975-08-27&atto.codiceRedazionale=075U0405&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Ludeke, S. G. (2014). Truth and fiction in the association between openness and education: The role of biased responding. Learning and Individual Differences, 35, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., Zhang, B., Antonoplis, S., & Mroczek, D. K. (2024). The effects of socioeconomic status on personality development in adulthood and aging. Journal of Personality, 92(1), 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, B., Richards, C., Cooper, M. L., Cozzarelli, C., & Zubek, J. (1998). Personal resilience, cognitive appraisals, and coping: An integrative model of adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makleff, S., Belfrage, M., Wickramasinghe, S., Fisher, J., Bateson, D., & Black, K. I. (2023). Typologies of interactions between abortion seekers and healthcare workers in Australia: A qualitative study exploring the impact of stigma on quality of care. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 23(1), 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. A., Upadhyay, U., Ralph, L., Biggs, M. A., & Foster, D. G. (2020). The effect of receiving versus being denied an abortion on making and achieving aspirational 5-year life plans. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 46(3), 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., Jansen, T., Hübner, N., & Lüdtke, O. (2023). Disentangling the association between the big five personality traits and student achievement: Meta-analytic evidence on the role of domain specificity and achievement measures. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. (2024). Report of the minister of health on the implementation of Law 194/78 on the social protection of maternity and voluntary termination of pregnancy—2022 data. Ministry of Health. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/it/pubblicazione/relazione-del-ministro-della-salute-sulla-attuazione-della-legge-contenente-norme-la/?tema=Salute%20della%20donna (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Perković, R., Hrkać, A., Dujić, G., Ćurlin, M., & Krišto, B. (2019). The influence of religiosity and personality dimensions on the attitudes about abortion. Psychiatria Danubina, 31(Suppl. 5), 805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, C. H., Samari, G., Foster, D. G., Gould, H., & Kimport, K. (2020). Emotions and decision rightness over five years following an abortion: An examination of decision difficulty and abortion stigma. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 248, 112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, B. B., Rocca, C. H., & Ralph, L. J. (2021). Certainty and intention in pregnancy decision-making: An exploratory study. Contraception, 103(2), 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1995). Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(5), 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvo, S., Bajos, N., Ducot, B., & Kaminski, M. (2003). Women’s life cycle and abortion decision in unintended pregnancies. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57(8), 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorhaindo, A. M., & Lavelanet, A. F. (2022). Why does abortion stigma matter? A scoping review and hybrid analysis of qualitative evidence illustrating the role of stigma in the quality of abortion care. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 311, 115271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, J. R., Tschann, J. M., Furgerson, D., & Harper, C. C. (2016). Psychosocial factors and pre-abortion psychological health: The significance of stigma. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 150, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J. B., Solano, A. C., & Liporace, M. F. (2019). Dysfunctional personality traits: Relationship with Five Factor Model, adaptation and symptomatology in a community sample from Buenos Aires. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 22(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbree, A.-R., Hornstra, L., Maas, L., & Wijngaards-de Meij, L. (2023). Conscientiousness as a predictor of the gender gap in academic achievement. Research in Higher Education, 64(3), 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin Lundell, I., Sundström Poromaa, I., Ekselius, L., Georgsson, S., Frans, Ö., Helström, L., Högberg, U., & Skoog Svanberg, A. (2017). Neuroticism-related personality traits are associated with posttraumatic stress after abortion: Findings from a Swedish multi-center cohort study. BMC Women’s Health, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, R., & Chopik, W. J. (2024). Explicating narrow and broad conceptualizations of environmental influences on personality. Journal of Personality, 92(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajenkowska, A., Nowakowska, I., Kaźmierczak, I., Rajchert, J., Bodecka-Zych, M., Jakubowska, A., Anderson, J. L., & Sellbom, M. (2022). The interplay between disinhibition and present-hedonistic time perspective in the relation between Borderline Personality Organization and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 186, 111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographics and VTP’s Related Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <30 years | 48 (39.3) |

| ≥30 years | 74 (60.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Province of residence | |

| Bari | 96 (78.7) |

| Outside Bari province | 25 (20.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) |

| Citizenship | |

| Italians | 115 (94.3) |

| Not Italians | 7 (5.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Marital Status | |

| In couples | 65 (53.3) |

| Not in couples | 55 (45.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.6) |

| Education Status | |

| Low educational level | 22 (18.0) |

| Medium educational level | 71 (58.2) |

| High educational level | 29 (23.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 66 (54.1) |

| Unemployed | 55 (45.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) |

| Live Births (number) | |

| 0 | 58 (47.5) |

| ≥1 | 64 (52.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Miscarriage (number) | |

| 0 | 105 (86.1) |

| ≥1 | 17 (13.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| VTP (number) | |

| 0 | 88 (72.1) |

| ≥1 | 34 (27.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Parity | |

| With children | 64 (52.5) |

| Without children | 36 (29.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Repeated VTP | |

| Yes | 34 (27.9) |

| No | 66 (54.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Gestational Age | |

| First 90 days | 118 (96.7) |

| Over 90 days | 4 (3.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Amenorrhea (weeks) | |

| ≤8 | 104 (85.2) |

| ≥9 | 14 (11.5) |

| Missing | 4 (3.3) |

| Foetal Malformations | |

| Yes | 5 (4.1) |

| No | 117 (95.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Certification Release | |

| Family planning counselling facilities | 48 (39.3) |

| Family Doctor | 23 (18.9) |

| Obstetrics-Gynaecology Service of the Healthcare Institute | 51 (41.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Urgency | |

| Yes | 32 (26.2) |

| No | 90 (73.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Type of VTP intervention | |

| Surgical | 1 (0.8) |

| Pharmacological | 119 (97.5) |

| Missing | 2 (1.6) |

| Antalgic Therapy | |

| General Anaesthesia | 3 (2.5) |

| Analgesia without Anaesthesia | 12 (9.8) |

| No Therapy | 105 (86.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.6) |

| Period between certification and VTP | |

| ≤14 days | 121 (99.2) |

| ≥15 days | 1 (0.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Test | Dimension | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Min–Max | Mean (SD) or Median [IQR] | ||

| BFQ | Extraversion | 122 | 47–106 | 76.11 (9.58) |

| Agreeableness | 122 | 58–102 | 80.34 (8.56) | |

| Conscientiousness | 122 | 56–116 | 84.49 (10.50) | |

| Emotional Stability | 122 | 33–104 | 65.47 (13.07) | |

| Openness | 122 | 52–109 | 80.61 (10.42) | |

| PID-5 | Negative affect | 122 | 0–15 | 7 [5–9] |

| Detachment | 122 | 0–13 | 4 [2–6] | |

| Antagonism | 122 | 0–12 | 2 [1–5] | |

| Disinhibition | 122 | 0–13 | 5 [2–7] | |

| Psychoticism | 122 | 0–14 | 4 [2–7] | |

| GDMS | Rational | 122 | 9–25 | 19 [16–23] |

| Intuitive | 122 | 8–25 | 18.12 (3.35) | |

| Dependent | 122 | 5–25 | 16 [14–19] | |

| Avoidant | 122 | 5–25 | 12 [10–16] | |

| Spontaneous | 122 | 5–25 | 13 [9–16] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorusso, L.; Bartolomeo, N.; Metta, M.E.; Gasparre, D.; Pignataro, P.; Caradonna, G.; Taurisano, P.; Trerotoli, P. Association Between Decision-Making Styles, Personality Traits, and Socio-Demographic Factors in Women Choosing Voluntary Pregnancy Termination: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100214

Lorusso L, Bartolomeo N, Metta ME, Gasparre D, Pignataro P, Caradonna G, Taurisano P, Trerotoli P. Association Between Decision-Making Styles, Personality Traits, and Socio-Demographic Factors in Women Choosing Voluntary Pregnancy Termination: A Cross-Sectional Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(10):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100214

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorusso, Letizia, Nicola Bartolomeo, Maria Elvira Metta, Daphne Gasparre, Patrizia Pignataro, Giulia Caradonna, Paolo Taurisano, and Paolo Trerotoli. 2025. "Association Between Decision-Making Styles, Personality Traits, and Socio-Demographic Factors in Women Choosing Voluntary Pregnancy Termination: A Cross-Sectional Study" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 10: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100214

APA StyleLorusso, L., Bartolomeo, N., Metta, M. E., Gasparre, D., Pignataro, P., Caradonna, G., Taurisano, P., & Trerotoli, P. (2025). Association Between Decision-Making Styles, Personality Traits, and Socio-Demographic Factors in Women Choosing Voluntary Pregnancy Termination: A Cross-Sectional Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(10), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100214