Empowering Parents of Adolescents at Elevated Risk of Suicide: Co-Designing an Adaptation to a Coach-Assisted, Digital Parenting Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Recruitment and Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. First Co-Design Workshop with Parents: Enablers and Barriers to Parental Empowerment

2.4.2. Co-Design Workshop with Young People: The Acceptability of Parent Empowerment in the Context of Suicide Prevention

2.4.3. Co-Design Workshop with Experts: Feasibility of a Therapist-Assisted Online Parenting Program to Support Parent Empowerment

2.4.4. Final Co-Design Workshop with Parents: Sense-Checking Themes of Parental Empowerment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

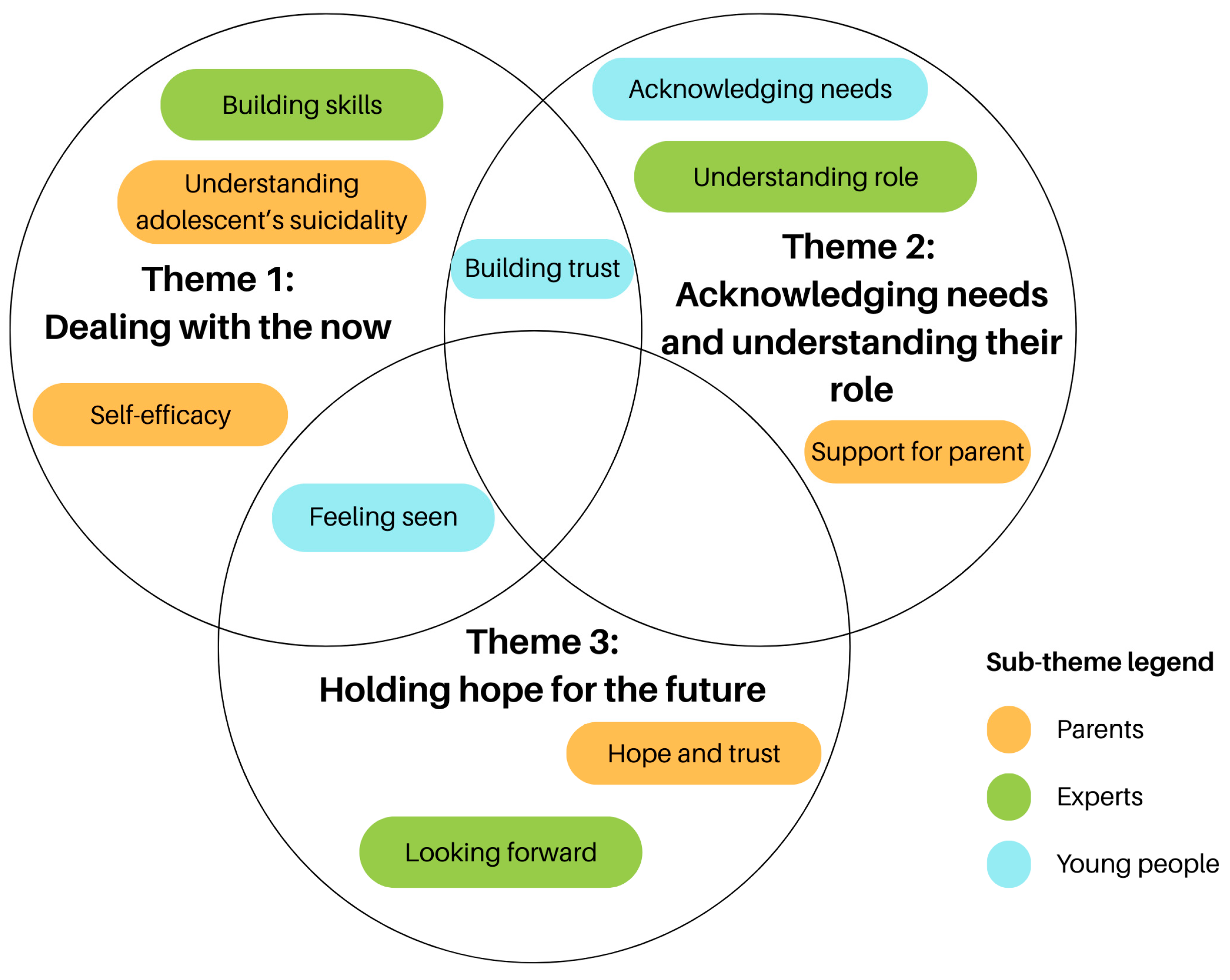

3.2. Identified Themes Facilitating the Empowerment of Parents Caring for a Suicidal Adolescent

3.2.1. Dealing with the Now

3.2.2. Acknowledging Needs and Understanding Their Role

3.2.3. Holding Hope for the Future

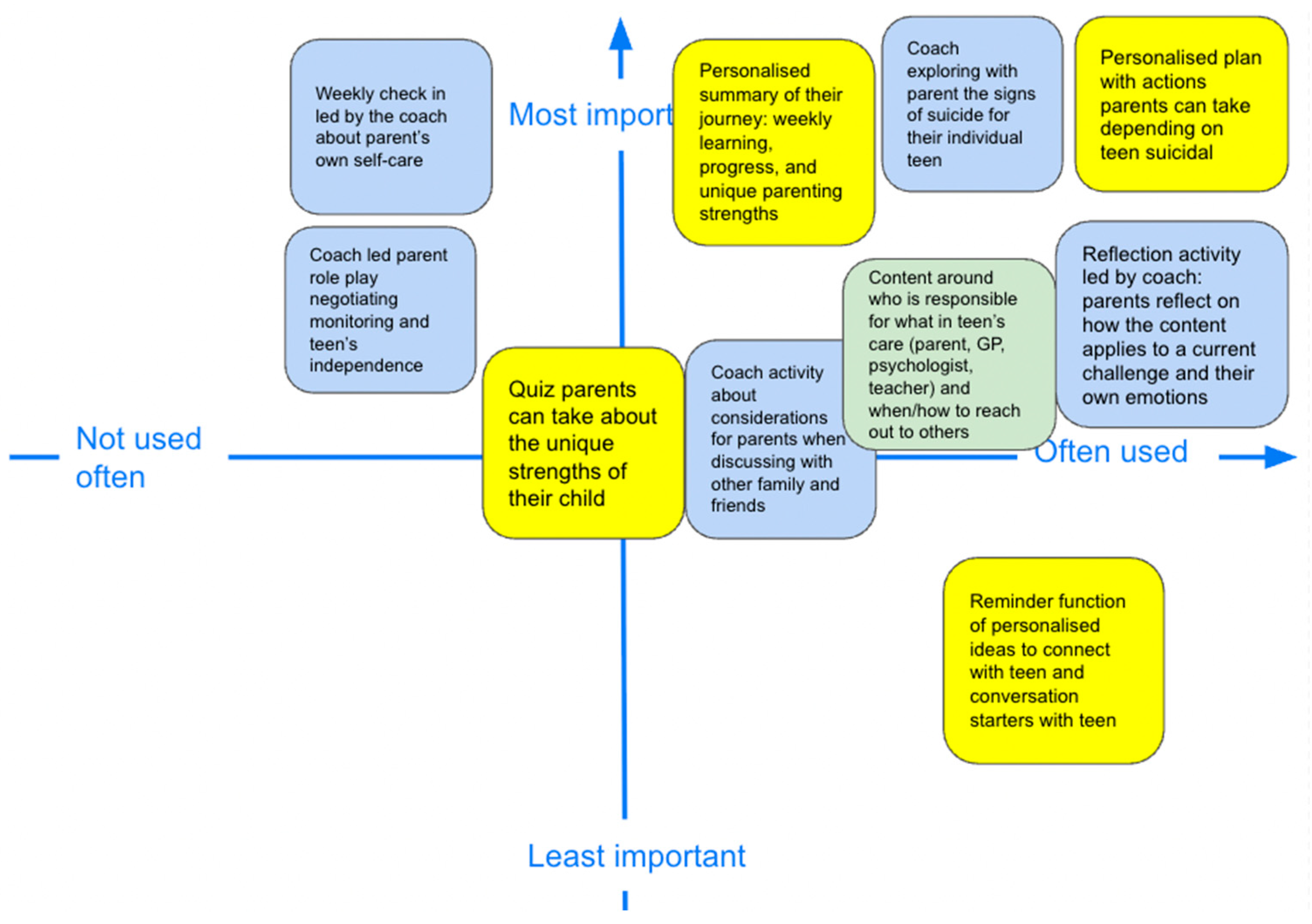

3.3. How Empowerment Could Be Embedded in the Technological System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PiP | Partners in Parenting |

| PiP+ | The highest level of the Partners in Parenting program which combines the online self-directed program with regular one-on-one coaching sessions via video conference |

| PiP-SP+ | Partners in Parenting—Suicide Prevention |

References

- Ahmadpour, N., Loke, L., Gray, C., Cao, Y., Macdonald, C., & Hart, R. (2023, April 23–28). Understanding how technology can support social-emotional learning of children: A dyadic trauma-informed participatory design with proxies. 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–17), Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohamed, A., Zhang, J., & Vyas, D. (2020, June 15–17). Magic machines for refugees. 3rd ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (pp. 76–86), Guayaquil, Ecuador. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K., & Wakkary, R. (2019, May 4–9). The magic machine workshops: Making personal design knowledge. 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13), Scotland, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S., Sanders, M. R., & Morawska, A. (2017). Who uses online parenting support? A cross-sectional survey exploring Australian parents’ internet use for parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, K. A., Kerr, J., Nambiar, S., Gallegos, D., Penny, R. A., Laws, R., & Byrne, R. (2024). A design thinking-led approach to develop a responsive feeding intervention for Australian families vulnerable to food insecurity: Eat, Learn, Grow. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 27(2), e14051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkamp, E. (2018). The promise of co-design for public policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(4), 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A. L., Christensen, H., Freeman, A., Fenton, K., Busby Grant, J., van Spijker, B., & Donker, T. (2016). A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(5), 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A., Melvin, G. A., Wu, L., Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Salvaris, C. A., Olivier, P., Jorm, A. F., & Yap, M. B. H. (2025). Understanding the lived experience and support needs of parents of suicidal adolescents to inform an online parenting programme: Qualitative study. BJPsych Open, 11(2), e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, T., & Lister, K. (2022, June 20–23). Creating stories of learning, for learning: Exploring the potential of self-narrative in education with ‘our journey’. 14th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (pp. 526–531), Venice, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, E. K., Horwitz, A. G., Yeguez, C. E., Ewell Foster, C. J., & King, C. A. (2018). Parental self-efficacy to support teens during a suicidal crisis and future adolescent emergency department visits and suicide attempts. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S384–S396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, S., Sinclair, J., & Hawton, K. (2008). Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: A descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, C. M. F., Melvin, G. A., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K. A., & Yap, M. B. H. (2019). The Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program for parents of adolescents with clinical anxiety or depression: Development and feasibility pilot. Internet Interventions, 18, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice: Self-compassion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A., Aliri, J., Balluerka, N., & Lameirinhas, J. (2019). Parenting styles and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene-Palmer, F. N., Wagner, B. M., Neely, L. L., Cox, D. W., Kochanski, K. M., Perera, K. U., & Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M. (2015). How parental reactions change in response to adolescent suicide attempt. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D. J., Rusanov, D., Winestone, B., Kaplan, R., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., & Melvin, G. (2023). Disclosure of suicidal ideation and behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Clinical Psychology Review, 101, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanington, B., & Martin, B. (2019). Universal methods of design expanded and revised: 125 Ways to research complex problems, develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. Rockport Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demissie, Z., Crosby, A. E., Stone, D. M., Gaylor, E., Wilkins, N., Lowry, R., & Brown, M. (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., Graaf, R. D., Gasquet, I., Girolamo, G. D., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina, M. E., Browne, M. A. O., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Tsang, C. H. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., … Üstün, T. B. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Killackey, E. (2023). Lived, loved, laboured, and learned: Experience in youth mental health research. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(12), 916–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantto, R., Lindkvist, R.-M., Jungert, T., Westling, S., & Landgren, K. (2023). Receiving a gift and feeling robbed: A phenomenological study on parents’ experiences of Brief Admissions for teenagers who self-harm at risk for suicide. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, C. W., Sanders, M. R., Rusby, J. C., & Crowley, R. N. (2012). Using consumer preference information to increase the reach and impact of media-based parenting interventions in a public health approach to parenting support. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsell, M. C., Greenleaf, M. N., Kombara, G. G., Sukhatme, V. P., & Lam, W. A. (2024). Engaging cancer care physicians in off-label drug clinical trials: Human-centered design approach. JMIR Formative Research, 8, e51604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, K. (2018). Affinity diagramming for collaboratively sorting UX findings and design ideas. Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/affinity-diagram (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Rheinberger, D., Baffsky, R., McGillivray, L., Zbukvic, I., Dadich, A., Larsen, M. E., Lin, P.-I., Gan, D. Z. Q., Kaplun, C., Wilcox, H. C., Eapen, V., Middleton, P. M., & Torok, M. (2023a). Examining the feasibility of implementing digital mental health innovations Into hospitals to support youth in suicide crisis: Interview study with young people and health professionals. JMIR Formative Research, 7, e51398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheinberger, D., Shand, F., Mcgillivray, L., Mccallum, S., & Boydell, K. (2023b). Parents of adolescents who experience suicidal phenomena—A scoping review of their experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostad, W. L., Moreland, A. D., Valle, L. A., & Chaffin, M. J. (2018). Barriers to participation in parenting programs: The relationship between parenting stress, perceived barriers, and program completion. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadka, O., Erel, H., Grishko, A., & Zuckerman, O. (2018, June 19–22). Tangible interaction in parent-child collaboration: Encouraging awareness and reflection. 17th ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children (pp. 157–169), Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H., Eiband, M., Ullrich, D., & Butz, A. (2018, April 21–26). Empowerment in HCI—A survey and framework. 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–14), Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, P., Saeri, A. K., & Bragge, P. (2020). Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomitsch, M., Wrigley, C., Borthwick, M., Ahmadpour, N., Frawley, J., Kocaballi, A. B., Nunez-Pacheco, C., & Straker, K. (2018). Design. Think. Make. Break. Repeat. A handbook of methods. BIS Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health of adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Yap, M. B. H., Lawrence, K. A., Rapee, R. M., Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Green, J., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Partners in parenting: A multi-level web-based approach to support parents in prevention and early intervention for adolescent depression and anxiety. JMIR Mental Health, 4(4), e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, M. B. H., Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. F. (2013). Where would young people seek help for mental disorders and what stops them? Findings from an Australian national survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1–3), 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identified Sub-Themes | Gap Identified Which Needs to Be Designed for Parent Empowerment | Concretised Feature in a Digital, Therapist-Assisted Parenting Intervention to Address the Sub-Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy |

| Personalised plan with actions parents can take depending on adolescent suicidal behaviour |

| Hope and Trust in Adolescent’s Recovery |

| Personalised record of learnings: weekly learning, progress, and unique parenting strengths |

| Building Skills |

| Reflection activity led by coach: parents reflect on how the content applies to a current challenge and their own emotions |

| Building Trust |

| Coach-led parent role play of a situation that requires negotiation of monitoring and adolescent’s independence |

| Understanding Role |

| Module content around who is responsible for what in adolescent’s care team (parent, GP, psychologist, teacher) and when/how to reach out to others |

| Support for Parent |

| Content and activity about considerations for parents when discussing with other family and friends |

| Understanding Adolescent’s Suicidality |

| Coach exploring with parent the signs of suicide for their adolescent |

| Demographic Characteristics | Parents | Young People | Experts |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Man | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Mean Age ± SD | 47.0 ± 4.94 | 21.0 ± 1 | |

| Experts’ Professions a | |||

| Clinician Researcher | 4 |

| Description of the Sub-Theme | Indicative Verbatim Quotes of Sub-Themes | |

|---|---|---|

| Dealing with the now sub-themes | ||

| Self-efficacy | For parents to be able to acquire and draw upon specific skills and knowledge while their adolescent is suicidal, parents described that it was important for them to have a sense of confidence that they can support their adolescent. Parents described that without such confidence, it would be challenging for them to be able to draw upon specific suicide prevention skills and knowledge. | “[The magic machine] would give Stacey [the parent in the vignette] the confidence to just broach the subject with Trevor [the adolescent in the vignette]. It would give her all the vocabulary to use when she’s having discussions with him… it’d give her confidence to implement what she’s learned” (Parent 4). |

| Understanding their adolescent’s suicidality | Parents described that for them to be able to engage in skills and knowledge related to adolescent suicide prevention when their adolescent is experiencing a suicidal crisis, they need to understand why their adolescent is suicidal, and what are the signs of escalating suicidal thoughts and behaviours specific to their own adolescent. | “(I’d like to) understand what’s underlying that behaviour. So, if they’re staying in their room what’s underlying that, is it because they’re feeling terrible about themselves and don’t want to talk to anyone and going down a spiral of negative thinking or are they just enjoying their time.” (Parent 1) |

| Building skills | Experts described that for parents to be able to support their adolescent during a suicidal crisis, they need to be supported to develop skills to respond in line with evidence-based best-practice suicide prevention strategies. | “It should be quite clear that this is the goal of our work. This is not psychotherapy. This is coaching, which is focused on developing [the parents’] skills” (Expert 2) |

| Building trust | Young people described that for parents to be able to successfully implement suicide prevention strategies, there first needs to be a sense of trust between the parent and adolescent. They highlighted the importance that parents can be understanding of what their adolescent is experiencing, noting that without this sense of being understood, they were less likely to trust their parent’s advice, even when well-intentioned. As such, building trust in their parent’s emotional insights is essential for young people to be more receptive of accepting help during their suicidal crises. | “I don’t think I trusted her to know really what was going on. And so then I did not trust any of her advice. If you don’t have a relationship where like, you’re both like trusting each other, then it’s really hard to then trust things you’re telling me to do.” (Young person 3) |

| Feeling seen | Young people described that for parents to be able to successfully implement suicide prevention strategies, and for their adolescents to be more receptive to such strategies, parents need to understand their adolescents’ difficulties in the context of who they are and their current experiences. Young people indicated that they would be less open to seeking help and receiving support from their parents if they considered that their parents viewed them as being ‘broken’ or in need of ‘fixing’. | “(Parents should be) seeing (their adolescent) like a person and, and like understanding they have feelings… it can’t just be like, ’I want to fix my broken son’… (the adolescents) are going to like be like, ‘oh, so you think there’s like something wrong with me. Great. Like, wow, news flash, there is something wrong with me’… But if the intention is like, ‘oh, you know, I really want to support you through this so I understand what you’re going through’. Um, they’ll feel that too.” (Young Person 2) |

| Acknowledging needs and understanding their role sub-themes | ||

| Support for parent | Parents described that to feel empowered to care for a suicidal adolescent, they need to be able to draw upon professional and personal support for themselves. Parents discussed such needs for support given that their consistent caretaking role can take a toll on their well-being. | “They’re still a child that needs us to be strong, which we can’t do all the time. And so we also need to have our own support and friends to help us when we’re struggling with all of that ourselves”. (Parent 1) |

| Understanding role | Experts described how parents need to be supported and to understand their role in caring for their adolescents to help them feel empowered. They discussed that at times, parents can feel that they are solely responsible for their adolescent’s health, education, and well-being. Therefore, parents need to understand that they are part of a team and can leverage the appropriate expertise of the adolescent’s care team (e.g., health professionals) to provide support. | “Their role is around support and being there rather than taking the control completely… For the parents to feel like… it’s not just them. It’s who else? Who else can the young person talk to? Who else can they get support from? So, it’s more of a shared team approach”. (Expert 1) |

| Acknowledging needs | Young people described the importance of parents reflecting and acting upon their own needs as a form of parent empowerment when caring for a suicidal adolescent. Further, young people described that when parents acknowledge their own needs and self-care, they also in turn model this skill to their adolescent. | “[I’d like her to] like self-care, like, ‘Oh, Mum’s actually taking care of herself. That’s cool. Maybe I should do a little bit myself or something’… Even modelling that behaviour is so important.” (Young person 2) |

| Building trust | Young people described how parents must trust the young person’s care team to uphold their duty of care in order to feel empowered in their role of supporting their adolescent. | “I was already connected with other supports that I was like, well, I’m already talking to all these people and I already am trying to work on all these things. You don’t have to be breathing down my neck to like work out what’s wrong or like work out if something has changed. Like someone else will work that out, you don’t need to work that out.” (Young person 3) |

| Holding hope for the future sub-themes | ||

| Hope and trust | Parents described that to feel a sense of empowerment when engaging in a parenting intervention, parents need to hold hope that with time their adolescent will eventually recover and have trust that the parenting strategies they learn will support their recovery. | “[Parents need to] understand that it’s not necessarily going to change overnight… but you still have to keep trying and you still have to keep giving that support… you have to sort of remain hopeful.” (Parent 4) |

| Feeling seen and looking forward | Young individuals described the importance of parents recognising the current state and difficulties faced by adolescents (i.e., feeling seen). Yet, they equally emphasised that parents should maintain hope that recovery is possible although it may require time and continued effort (i.e., looking forward). Echoing young people’s descriptions, experts discussed that for parents to feel empowered, they need to believe that their adolescent’s suicidal thoughts and behaviours can be overcome by the parent supporting the adolescent holistically (i.e., not only focusing on suicidality). | “It’s like having enough faith that you’ll make it to the end but being realistic with where you’re at… Of course, like what [the adolescent] is going through is tough and is really, really like worrying. I’d be really worried. But this is, this is the long haul. And then also helping to understand that after you’re able to have a… having opened up, that’s not the end. Like there’s more to it.” (Young Person 2) “This is still your child. This is still, this person is going through a difficult time with all these things going on. So how do we keep seeing them and how do we keep hearing and holding out for who they are and the hope for the future and not get too fixated on the safety on its own.” (Expert 1). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, A.; Wu, L.; Melvin, G.; Cardamone-Breen, M.; Broomfield, G.; Seguin, J.; Salvaris, C.; Xie, J.; Basur, D.; Bartindale, T.; et al. Empowering Parents of Adolescents at Elevated Risk of Suicide: Co-Designing an Adaptation to a Coach-Assisted, Digital Parenting Intervention. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100199

Cao A, Wu L, Melvin G, Cardamone-Breen M, Broomfield G, Seguin J, Salvaris C, Xie J, Basur D, Bartindale T, et al. Empowering Parents of Adolescents at Elevated Risk of Suicide: Co-Designing an Adaptation to a Coach-Assisted, Digital Parenting Intervention. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(10):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100199

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Alice, Ling Wu, Glenn Melvin, Mairead Cardamone-Breen, Grace Broomfield, Joshua Seguin, Chloe Salvaris, Jue Xie, Dhruv Basur, Tom Bartindale, and et al. 2025. "Empowering Parents of Adolescents at Elevated Risk of Suicide: Co-Designing an Adaptation to a Coach-Assisted, Digital Parenting Intervention" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 10: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100199

APA StyleCao, A., Wu, L., Melvin, G., Cardamone-Breen, M., Broomfield, G., Seguin, J., Salvaris, C., Xie, J., Basur, D., Bartindale, T., McNaney, R., Olivier, P., & Yap, M. B. H. (2025). Empowering Parents of Adolescents at Elevated Risk of Suicide: Co-Designing an Adaptation to a Coach-Assisted, Digital Parenting Intervention. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(10), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100199