The Impact of a School Dog on Children’s Social Inclusion and Social Climate in a School Class

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective and Analytical Framework

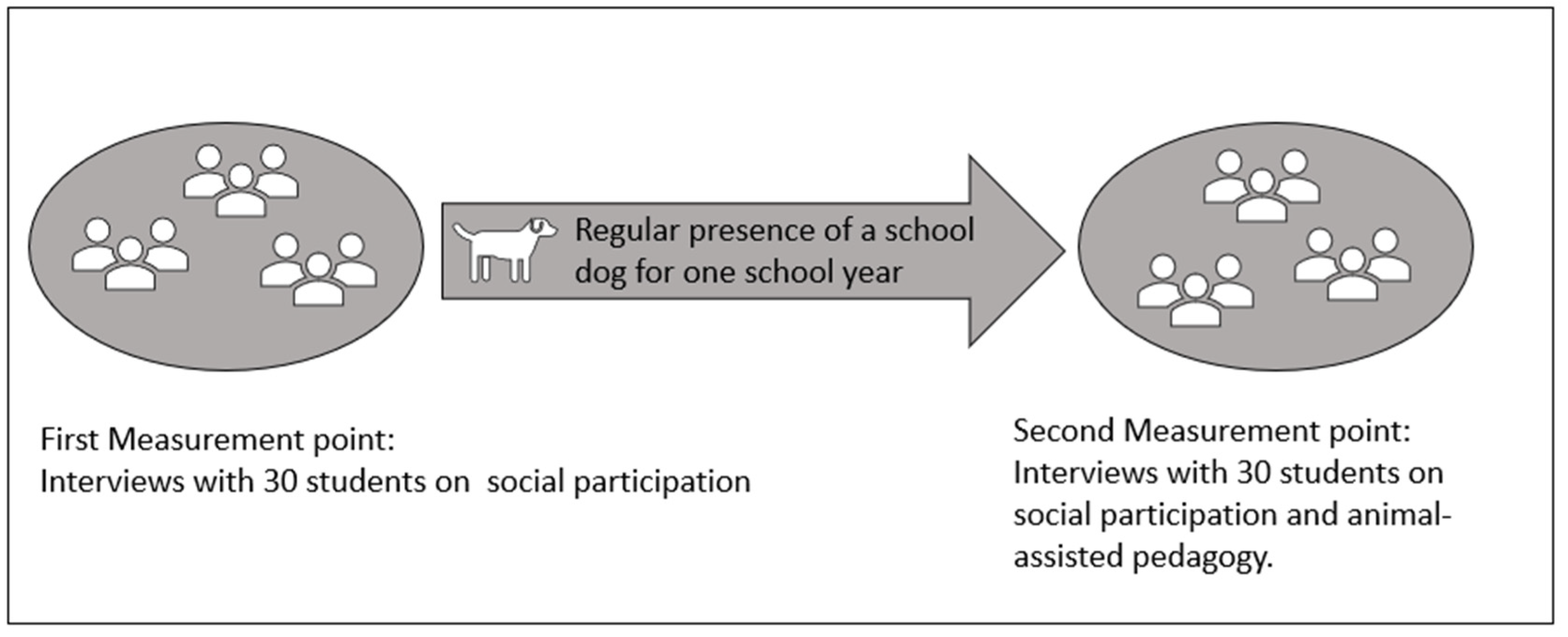

2.2. Method and Design

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Analysis

- Initiating text work with the aid of the postscripts and the full transcripts of the problem-centered interviews.

- Coding of pre-formulated main categories: (A) Social climate and social participation, (B) Learners’ perceptions of the teacher, and (C) Comments on Attributes and characteristics of dogs, regardless of the topic of social climate.

- Category formation: Coding along the main categories A in (a) Evaluation: Is the statement positive, i.e., advocating or pointing out advantages or positive developments regarding aspects of one of the central themes? (animal-assisted pedagogy, social interaction), neutral or negative, criticizing, highlighting a problem? (positive, problematic, and unclear/neutral) and in (b) Context: Is a direct reference to animal-assisted pedagogy made or not? (dog, no dog). Moreover, the main category A was categorized in a differentiated manner, in (c) References (to oneself, to individuals (others), and everyone; that is to say, the whole class and generally formulated statements).

- Formation of subcategories along the main category A: Coding as Working atmosphere, Interpersonal, and Well-being.

- Category formation: Coding along the main category B in Assessment (positive, problematic, and unclear/neutral).

- Combination of subcategories and emphasis onJustification patterns as further subcategories along the categories Working atmosphere, Interpersonal, and Well-being and further differentiation of the justification patterns if necessary. Two predominant and frequently encountered categories for justification/explanation are “actions for the dog” and “actions through the dog”.

- The statements about the teacher from the post-interviews are coded into the Impact chains (Effect chains) category. The impact refers to the interaction of teacher–dog—class (T-D-C combined in various ways).

- Along the main category C: The Statements about attributes and the Meaning attributions to dogs are coded into three thematic subcategories.

- Expanding on the subcategory Individuals and Everyone as well as Context dog at the second measurement point, selected statements are coded as the category Observations of others interacting with the dog.

3. Results

3.1. Part 1: Implications of Animal-Assisted Pedagogy for Social Participation and Social Climate

3.1.1. Working Atmosphere

“So yes: we’ve been very considerate of [dog’s name] there as much as possible. And yes, things got much calmer because everyone simply listens to the rules and cares for the dog”(F8_28, Group 2, Segment 52).

“Well, I just think it’s great (…). I can sometimes concentrate better when there’s [dog’s name] next to me”(H6_5, Group 2, Segment 28).

Pre: “Yes, because we don’t behave all the time”(F5_4, Group 1, Segment 10).

Post: “So when the dog is around, there’s no stress really, but when there are other teachers around (who do not teach animal-assisted), there’s stress sometimes, and that’s still the same as always”(F5_21, Group 2, Segment 3).

“So, I can concentrate better because the class is quiet. However, I cannot concentrate so well when the dog is there because I always want to stroke the dog, and I also want him to develop trust in me”(F5_12, Group 2, Segment 35).

3.1.2. Well-Being and Uneasiness

“Because you feel somehow differently there, the room feels more alive because, in the class, you only move your hand, yeah. And then everything is just a little bit more alive”(H6_21, Group 2, Segment 44).

“So, you look forward to doing math a lot more. I never really wanted to go to math before, it was boring, and I always wanted to just go home (laughs). But now I’m looking forward to math when (…) but only when the dog is there”(F8_7, Group 2, Segment 33).

“So, the first time [dog’s name] was there, I was excited at first, I was happy the whole day, while the last few days I wasn’t excited because I already knew [dog’s name], I was just happy that she was with us. I was just happy all the time then, too. Whenever she was there”(F5_13, Group 2, Segment 18).

“It’s just that when you’re a little bit stressed, for example (…) writing a paper or something (…) and then [dog’s name] is sort of lying there quite relaxed, then you also become sort of relaxed”(S5_14, Group 2, Segment 63–65).

“R (Respondent): I feel, like using a metaphor, for example, if you mix cocoa with milk now. Then it turns into a drink. And this drink certainly tastes good. And that’s the same feeling. I (Interviewer): Just a feeling of well-being. R: Yes. I: A little bit of enjoyment, relaxation too? R: A bit of relaxation (unintelligible). I: OK. Why is that so? Why do you get that feeling when there’s a dog around? R: I don’t exactly know, but it’s just that kind of feeling. It’s something I can only describe myself a little. I: OK. And you have this feeling? R: I think a few of us have, I’m not alone”(F8_1, Group 2, Segment 48–56).

“Yes, only some. Well, for example, Fe24 is a little frightened of dogs now, but generally, she’s also frightened of cats and stuff. That’s why, but she’s getting used to it, I think, anyway”(F5_18, Group 2, Segment 72).

“Yes, so (…) I’m not as scared (…) anymore, doesn’t faze me as much”(F8_7, Group 2, Segment 152–153).

“I was a bit sad because the dog never came to me”(F8_30, Group 2, Segment 28–43).

3.1.3. Interpersonal Dimension

“Because before, everybody kind of had their own goal. Like, for example, some wanted good grades, others wanted to be cool, and others just kept to themselves. And now, we all have our shared goal, that the dog stays here”(F8_3, Group 2, Segment 62–64).

“When the dog is around, there’s no stress really”(F5_21, Group 2, Segment 3).

“There’s less conflict between people, between groups”(F8_6, Group 2, Segment 2).

3.1.4. Perception of the Teacher

“R: Firstly, I used to have such earache, or something (…) had kind of scared me constantly when Mr. FBO sort of started shouting like that. But somehow, since the dog has been there, that’s no longer the case”(F8_22, Group 2, Segment 50).

“R: Well, I noticed that Mr. FBO has become a bit more cheerful. I’ve never seen Mr. FBO laugh since [dog’s name] was there. Never. I: Before you mean? R: I never saw Mr. FBO laughing before. I: OK. R: Never. I: Yes. R: He’s been laughing since [dog’s name] came. He laughs (…) whenever he wants. I: OK. R: So, the lessons with Mr. FBO have (…) so are more (…) fun”(F8_1, Group 2, Segment 107–115).

3.2. Results in Part 2: Potential of Animal-Assisted Education

“So, it [a dog] is a special animal, a living being in the truest sense. And that’s why I think you should also be good to animals […]. So, I think it’s special, something so special”(F5_18, Group 2, Segment 50).

“Yes, he [teacher] said that the dog would be quite beneficial for me, but (…). I: You don’t see it that way necessarily. R: No”(F8_6, Group 2, Segment 38–40).

“R: As far as I’ve seen, whenever a dog has come to one of our boys, they’ve been quite careful. I: OK. R: So, they weren’t as, you know, rough as they were to other students, for instance, but rather more careful with the animal. I: Oh, really? R: Yeah, so give the dog a stroke, or whatever, but they didn’t, for example, they didn’t talk so loudly either. They didn’t yell or (…), just very quietly. I: Would you have expected this before? R: Well, with some of them, I would have, but I was still a little bit unsure with others as to whether they would show a little bit of change with the animals. I: OK. Would you say, that they were somehow different? R: Yes”(F8_8w, Group 2, Segment 54–62).

“So, for example, F29, he is actually, actually also totally loud and such, but he is now fully concentrated, and he also asks me for help when he doesn’t understand something, and this is something that has surprised me a bit I: And this is quite new? OK R: Yes, so it was like this in fifth grade. But then we had another teacher, who always played music for us. But then, a long time passed where F29 didn’t do anything at all. And now, he makes the effort again, and that has surprised me so positively. I: When did he start doing things again? R: I don’t know, now for a month, or two. I: OK, yeah good. Can you figure out why that is, or is it something you just noticed? R: I just noticed it”(F8_3, Group 2, Segment 48–54).

“I thought (…) yes, I thought, for example, F25 (…) I thought he was giving the dog more attention. But he’s not giving him any attention at all. So, he doesn’t pay attention to the dog. So as if he wasn’t there. I: OK. R: Yes. I: You wouldn’t have thought so? R: Yeah, I just thought (…) looking more at him or something, but he doesn’t at all. He is fully focused on the work”(F8_7, Group 2, Segment 143–147).

“R: Well, I also think that they are looking for a bit of a connection with the dog because it distracts them a bit from the work they are doing. And that makes it easier to work afterwards. I: Why do you think you can handle it better afterwards? R: Because maybe your head was somewhere else for a while and you had the chance to clear your head a bit. Thanks to the dog that was there”(F8_18, Group 2, Segment 14–16).

“R: The dog is indeed present, and Mr. FBO gives us his deepest trust because of the dog’s presence. And the dog is, in fact, just like a child for Mr. FBO. Because, of course, he raised her, [dog’s name]”(F8_1, Group 2, Segment 75).

“R: Yes. We have to give [dog’s name] the greatest sense of security. Out of everyone in the class, she is our (…), she’s our guest. And after all, Mr. FBO trusts in us to take care of her”(F8_1, Group 2, Segment 77).

“I think it’s also quite nice for her if she doesn’t have to leave [dog’s name] at home, she still can watch over her as well while doing lessons”(S5_20, Group 2, Segment 42).

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion concerning the State of Research

4.2. Discussion concerning Role Theory and Explanatory Approach to Animal-Assisted Education in School

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- The presence of a school dog appears to influence social roles. On one hand, existing social roles are altered, while on the other hand, new social roles emerge, particularly the “Caregiver” role, in which students feel the need to take responsibility for and care for the animal. As a result, mutual perceptions between students and between students and their teachers improve, leading to a more positive image of each other.

- Animal-assisted pedagogy leads to a reduction in stereotypes and individual prejudices and a transformation of norms within the school environment. Whereas previous social norms led to exclusion or differentiation from others, there is now a shift towards more appreciative and respectful interactions.

- Animal-assisted pedagogy presents an opportunity for social participation through shared interests and goals among students and between students and their teacher. Previously, differences were employed as markers of identity, but now, the shared experience of being taught with the assistance of an animal becomes the common bond for identification. However, the potential risk of exclusion stemming from disinterest needs to be further explored.

- Animal-assisted pedagogy fosters improved pro-social behavior, mood, and student empathy, highlighting the strong attachment-like relationships cultivated with school dogs, while jealousy and overwhelm may pose a threat to the positive effects.

- Animal welfare is relevant to both the well-being of animals and to educational processes. Reinforcing and promoting care for the animal (caretaker’s role) establishes the foundation for the effects of animal-assisted interventions, while simultaneously practicing animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Böttinger, T. Förderbedarf gleich Ausgrenzung?: Ein systematischer Forschungsreview zur sozialen Dimension schulischer Inklusion in der Primarstufe in Deutschland. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2021, 13, 216–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, S.; Sahli Lozano, C.; Torchetti, L.; Lüthi, M. Zusammenhänge des peerbezogenen Klassenklimas und der sozialen Partizipation von Schüler*innen mit kognitiven und sozial-emotionalen Beeinträchtigungen. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2022, 14, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Krawinkel, S.; Südkamp, A.; Tröster, H. Soziale Partizipation in inklusiven Grundschulkassen: Bedeutung von Klassen-und Lehrkraftmerkmalen. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2017, 9, 277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, R. Die soziale Partizipation von Schüler(inne)n in Lerngruppen der inklusiven Grundschule. In Grundschulpädagogik Zwischen Wissenschaft und Transfer: Jahrbuch Grundschulforschung; Donie, F.C., Foerster, M., Obermayr, A., Deckwerth, G., Kammermeyer, G., Lenske, G., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Schürer, S. Soziale Partizipation von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf in den Bereichen Lernen und emotionale-soziale Entwicklung in der allgemeinen Grundschule: Ein Literaturreview. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2020, 12, 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, Y.; Blumenthal, S. Zur Situation von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im Bereich emotionale und soziale Entwicklung im inklusiven Unterricht.: Longitudinale Betrachtung von Klassenklima, Lehrer-Schüler-Beziehung und sozialer Partizipation. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Crede, J.; Wirthwein, L.; Steinmayr, R.; Bergold, S. Schülerinnen und Schüler mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im Bereich emotionale und soziale Entwicklung und ihre Peers im inklusiven Unterricht.: Unterschiede in sozialer Partizipation, Schuleinstellung und schulischem Selbstkonzept. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2019, 33, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbriggen, C.; Venetz, M. Soziale Partizipation und aktuelles Erleben im gemeinsamen Unterricht. Empirische Pädagogik 2016, 30, 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Henke, T.; Bosse, S.; Lambrecht, J.; Jäntsch, C.; Jaeuthe, J.; Spörer, N. Mittendrin oder nur dabei?: Zum Zusammenhang zwischen sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf und sozialer Partizipation von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2017, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vock, M.; Gronostaj, A.; Kretschmann, J.; Westphal, A. “Meine Lehrer mögen mich”—Soziale Integration von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im gemeinsamen Unterricht in der Grundschule: Befunde aus dem Pilotprojekt “Inklusive Grundschule” im Land Brandenburg. DDS—Die Dtsch. Sch. 2018, 110, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Felder, F. Die Grenzen eines Rechts auf schulische Inklusion und die Bedeutung für den Gemeinsamen Unterricht. Psychol. Erzieh. Und Unterr. 2014, 62, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, A. Hunde im Schulalltag: Grundlagen und Praxis, 5th ed.; Ernst Reinhardt Verlag: München, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kotrschal, K.; Ortbauer, B. Behavioral effects of the presence of a dog in a classroom. Anthrozoös 2003, 16, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergovich, A.; Monshi, B.; Semmler, G.; Zieglmayer, V. The effects of the presence of a dog in the classroom. Anthrozoös 2002, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, K.; Brelsford, V.L.; Dimolareva, M.; Mare’chal, L.; Pennigton, K.; Rowan, E. Can dogs reduce stress levels in school children? effects of dog-assisted interventions on salivary cortisol in children with and without special educational needs using randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brelsford, V.L.; Meints, K.; Gee, N.R.; Pfeffer, K. Animal-assisted interventions in the classroom: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A.M.; Morreale, S.; Field, C.A.; Hussein, Y.; Barry, M.M. What Works in Enhancing Social and Emotional Skills Development during Childhood and Adolescence?: A Review of the Evidence on the Effectiveness of School-Based and out-of-School Programmes in the UK; Health Promotion Reaearch Centre: Galway, Ireland, 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a809c17e5274a2e87dbaca5/What_works_in_enhancing_social_and_emotional_skills_development_during_childhood_and_adolescence.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Dicé, F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Menna, L.F.; Freda, M. Meeting the emotion!: Application of the Federico II Model for pet therapy to an experience of animal assisted education (AAE) in a primary school. Prat. Psychol. 2017, 23, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Haire, M.E.; McKenzie, S.J.; McCune, S.; Slaughter, V. Effects of Classroom Animal-Assisted Activities on Social Functioning in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014, 20, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, A.; Borgi, M.; Francia, N.; Alleva, E.; Cirulli, F. Use of assistance and therapy dogs for children with autism spectrum disorders: A critical review of the current evidence. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Pieve, G.; Voglino, G.; Siliquini, R. Animal-assisted intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wice, M.; Goyal, N.; Forsyth, N.; Noel, K.; Castano, E. The Relationship Between Humane Interactions with Animals, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior among Children. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2020, 8, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, H.; Beetz, A.; Kotrschal, K.; Turner, D.C.; Uvnäs-Morberg, K. Bindung zu Tieren: Psychologische und Neurobiologische Grundlagen Tiergestützter Interventionen; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, E.; Brandl Denson, E.; Mueller, M.K.; Gandenberger, J.; Morris, K.N. Human-animal-environment interactions as a context for youth social-emotional health and wellbeing: Practitioners’ perspectives on processes of change, implementation, and challenges. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 41, 32823146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, R.; Christley, R.; Kordas, K.; Joinson, C.; Meints, K.; Gee, N.; Westgarth, C. Companion Animals and Child/Adolescent Development: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beetz, A.; Uvnäs-Morberg, K.; Julius, H.; Kotrschal, K. Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beetz, A.; Julius, H.; Turner, D.C.; Kotrschal, K. Effects of social support by a dog on tress modulation in male children with insecure attachment. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, J.; Lessard, L.M.; Rastogi, R.; Schacter, H.L.; Smith, D.S. Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombeck, M. Tiergestützte Pädagogik—Soziale Teilhabe—Inklusive Prozesse; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung; Rowohlt: Reinbeck, IA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Groeben, N.; Wahl, D.; Schlee, J.; Scheele, B. Das Forschungsprogramm Subjektive Theorien: Eine Einführung in Die Psychologie des Reflexiven Subjekts; Francke: Tübingen, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Laucken, U. Naive Verhaltenstheorie: Ein Ansatz zur Analyse des Konzeptrepertoires, Mit Dem im Alltäglichen Lebensvollzug das Verhalten der Mitmenschen Erklärt und Vorhergesagt Wird, 1st ed.; University of Tübingen: Tübingen, Germany; Klett: Stuttgart, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, H.-D. Pädagogisches Verstehen: Subjektive Theorien und erfolgreiches Handeln von Lehrkräften. In Verstehen: Psychologischer Prozess und Didaktische Aufgabe; Reusser, K., Reusser-Weyneth, M., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 1994; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U.; von Kardorff, E.; Steinke, I. (Eds.) Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch; Rowohlt: Reinbek, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U.; von Kardorff, E.; Steinke, I. Was ist qualitative Forschung? Einleitung und Überblick. In Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch, 11th ed.; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; Rowohlt: Reinbek, Germany, 2015; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Krappmann, L. Soziologische Dimensionen der Identität: Strukturelle Bedingungen für die Teilnahme an Interaktionsprozessen. Konzepte der Humanwissenschaften, 4th ed.; Klett-Cotta: Stuttgart, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, K. Erziehungswissenschaft im Aufbruch. Eine Einführung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung 1985, 1, 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, N.R.; Fine, A.H.; Schuck, S. Animals in Educational Settings: Research and Practice. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions, 4th ed.; Fine, A.H., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualitätsnetzwerk Schulbegleithunde e.V. Kampagne Gleichwürdigkeit. 2022. Available online: https://schulbegleithunde.de/kampagne-gleichwuerdigkeit/ (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Agsten, L. Schulhundweb. Qualitätsnetzwerk Schulbegleithunde e.V. 2005. Available online: https://schulhundweb.de/index.php?title=Hauptseite (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (MSB NRW). Rechtsfragen zum Einsatz eines Schulhundes. 2015. Available online: https://www.schulministerium.nrw/sites/default/files/documents/Allgemeine-Hinweise-Schulhund.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Helfferich, C. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten: Manual für die Durchführung Qualitativer Interviews, 4th ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (MSB NRW). Das Schulwesen in Nordrhein-Westfalen aus Quantitativer Sicht 2017/2018: Statistische Übersicht Nr. 399. 2018. Available online: https://www.schulministerium.nrw/sites/default/files/documents/Quantita_2017.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Dresing, T.; Pehl, T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse: Anleitung und Regelsysteme für Qualitativ Forschende; Eigenverlag: Marburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Grundlagentexte Methoden, 3rd ed.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein, A.; Scherzinger, M. Soziale Interaktionen als Grundbaustein der Beziehung zwischen Lehrperson und Schüler*innen. In Soziale Eingebundenheit. Sozialbeziehungen im Fokus von Schule und LehrerInnenbildung; Hagenauer, G., Raufelder, D., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hannover, B.; Zander, L.; Wolter, I. Die sozial-kognitive Theorie des Beobachtungslernens. In Pädagogische Psychologie; Seidel, T., Krapp, A., Eds.; Beltz Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 162–163. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mombeck, M.M.; Albers, T. The Impact of a School Dog on Children’s Social Inclusion and Social Climate in a School Class. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14010001

Mombeck MM, Albers T. The Impact of a School Dog on Children’s Social Inclusion and Social Climate in a School Class. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMombeck, Mona M., and Timm Albers. 2024. "The Impact of a School Dog on Children’s Social Inclusion and Social Climate in a School Class" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 1: 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14010001

APA StyleMombeck, M. M., & Albers, T. (2024). The Impact of a School Dog on Children’s Social Inclusion and Social Climate in a School Class. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14010001