Tumblr Facts: Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tumblr Peculiarities

1.2. Online Self-Disclosure and Its Antecedents: Social Compensation vs. Enhancement

1.3. The Present Study

- RQ1:

- Will Tumblr users show a higher willingness to self-disclose on Tumblr compared to other SNSs?

- RQ2:

- Will social anxiety, self-esteem, POSI, and negative emotionality directly impact self-disclosure on Tumblr and other SNSs?

- RQ3:

- Will POSI mediate the impact of social anxiety and self-esteem on self-disclosure on Tumblr and other SNSs?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. General Social Networking Site Use

2.2.2. Preference for Online Social Interactions

2.2.3. Negative Emotionality

2.2.4. Self-Esteem

2.2.5. Social Anxiety

2.2.6. Self-Disclosure on Tumblr and Other Social Networking Sites

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tumblr Use: Frequency and Practices

3.2. Psychological Variables Related to Tumblr Use: A First Look

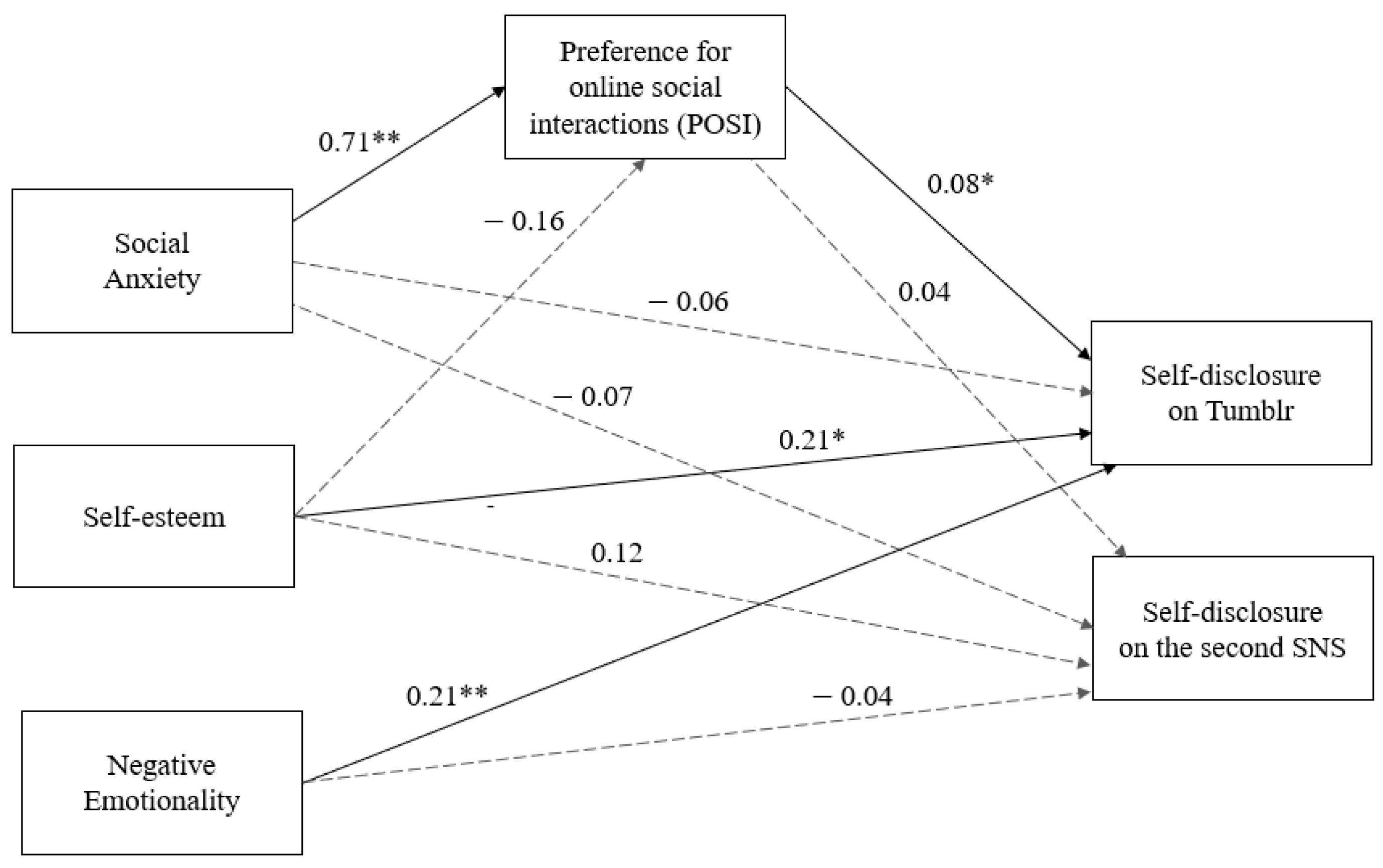

3.3. Results of the Path Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowden-Green, T.; Hinds, J.; Joinson, A. Understanding Neuroticism and Social Media: A Systematic Review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. Nativi Digitali; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.C.; Sun, X.J.; Zhou, Z.K. The Type, Function and Influencing Factors of Online Self-Disclosure. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 2, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlega, V.J.; Metts, S.; Petronio, S.; Margulis, S.T. Self-Disclosure; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shane-Simpson, C.; Manago, A.; Gaggi, N.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Why Do College Students Prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site Affordances, Tensions between Privacy and Self-Expression, and Implications for Social Capital. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. What Does Media Use Reveal about Personality and Mental Health? An Exploratory Investigation among German Students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 0191810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, A. Disturbing Hegemonic Discourse: Nonbinary Gender and Sexual Orientiation Labeling on Tumblr. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, B.J. Where I Can Be Myself... Where I Can Speak My Mind”: Networked Counterpublics in a Polymedia Environment. New Media Soc. 2015, 17, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel Eginli, A.; Ozmelek Tas, N. Interpersonal Communication in Social Networking Sites: An Investigation in the Framework of Uses and Gratification Theory. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, F.J.; Stein, C.H. Behind the Hashtag: Online Disclosure of Mental Illness and Community Response on Tumblr. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 67, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We are Social & Hootsuite. Digital 2021. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2021 (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Tiidenberg, K.; Hendry, N.A.; Abidin, C. Tumblr; Digital Media and Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-5095-4110-2. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, J. Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms. Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 2056305119867442. [Google Scholar]

- G.W.I. Tumblr and Pinterest Are the Fastest Growing Social Platforms. Available online: https://blog.gwi.com/chart-of-the-day/tumblr-and-pinterest-are-the-fastest-growing-social-platforms/ (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Statista. Porn Ban Hits Tumblr Where It Hurts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/17378/tumblr-traffic/ (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Datareportal. Digital 2021: Local Country Headlines. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-local-country-headlines (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Riva, G. Psicologia Dei Nuovi Media. Azione, Presenza, Identità E Relazioni; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haimson, O.L.; Dame-Griff, A.; Capello, E.; Richter, Z. Tumblr Was a Trans Technology: The Meaning, Importance, History, and Future of Trans Technologies. Fem. Media Stud. 2019, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurovac, E. Teen Screenshot: Forme serializzate della narrazione identitaria. Mediascapes J. 2016, 7, 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Polledo, E. Chronic Media Worlds: Social Media and the Problem of Pain Communication on Tumblr. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 2056305116628887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Ralston, R. Queer identity online: Informal learning and teaching experiences of LGBTQ individuals on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. I Social Network; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, M.M.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Coda, A.; Jang, Y.; Song, Y.; Rosé, C.P. Phans, Stans and Cishets: Self-Presentation Effects on Content Propagation in Tumblr. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Web Science, Southampton, UK, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, P.H.B. TUMBLR: Homogeneity and heterogeneity, production and reproduction of expenditure. Rev. FAMECOS-Mídia Cult. E Tecnol. 2016, 23, 21071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turkle, S. Life on the Screen; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Misailidou, E. Social Media Fandom: The Construction of Identity in the Cases of “The 100” and “Once Upon A Time” Tumblr Communities. In Proceedings of the 2017 Wireless Telecommunications Symposium WTS, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, S.; Procyk, J.; Neustaedter, C. “alksjdf; Lksfd” Tumblr and the Fandom User Experience. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 June 2014; pp. 775–784. [Google Scholar]

- Kunert, J. The Footy Girls of Tumblr: How Women Found Their Niche in the Online Football Fandom. Commun. Sport 2021, 9, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, A. Tumbling into Queer Utopias and Vortexes: Experiences of LGBTQ Social Media Users on Tumblr. J. Homosex. 2019, 66, 1715–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seko, Y.; Lewis, S.P. The Self—Harmed, Visualized, and Reblogged: Remaking of Self-Injury Narratives on Tumblr. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, B.W.; Haimson, O. Building an Online Community of Care: Tumblr Use by Transgender Individuals. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender & IT, Heilbronn, Germany, 14–15 May 2018; pp. 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tiidenberg, K. Bringing Sexy Back: Reclaiming the Body Aesthetic via Self-Shooting. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2014, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Miller, Q. Trans media moments: Tumblr, 2011–2013. Telev. New Media 2014, 15, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, P.; Robards, B.J.; Hanckel, B.; Vivienne, S.; Churchill, B. Hey, I’m having these experiences”: Tumblr use and young people’s queer (dis) connections. Int. J. Commun. 2019, 3, 2239–2259. [Google Scholar]

- Whannel, G. News, Celebrity, and Vortextuality: A Study of the Media Coverage of the Michael Jackson Verdict. Cult. Politics 2010, 6, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Taylor, D.A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.; Bin, Y.S.; Campbell, A. Comparing Online and Offline Self-Disclosure: A Systematic Review. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.E.R. The Facebook Paths to Happiness: Effects of the Number of Facebook Friends and Self-Presentation on Subjective Well-Being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazer, J.P.; Murphy, R.E.; Simonds, C.J. I’ll See You on ‘“Facebook”’: The Effects of Computer-Mediated Teacher Self-Disclosure on Student Motivation, Affective Learning, and Classroom Climate. Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Preadolescents’ and Adolescents’ Online Communication and Their Closeness to Friends. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, K.Y.; Bargh, J.A. Coming out in the Age of the Internet: Identity” Demarginalization” through Virtual Group Participation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Preference for Online Social Interaction: A Theory of Problematic Internet Use and Psychosocial Well-Being. Commun. Res. 2003, 30, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Theory and Measurement of Generalized Problematic Internet Use: A Two-Step Approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.W.Y.; Cheung, C.M.K. Problematic Use of Social Networking Sites: The Role of Self-Esteem. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2014, 9, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S.E. Relations among Loneliness, Social Anxiety, and Problematic Internet Use. CyberPsychology Behav. 2007, 10, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Heimberg, R.G. A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of Anxiety in Social Phobia. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.M.; Wells, A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment; Heimberg, R.G., Liebowitz, M.R., Hope, D.A., Schneier, F.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Alden, L.E.; Bieling, P. Interpersonal Consequences of the Pursuit of Safety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998, 36, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, B.A.; Turk, C.L.; Heimberg, R.G.; Fresco, D.M.; Hantula, D.A. The Internet: Home to a Severe Population of Individuals with Social Anxiety Disorder? Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Bargh, J.A. Plan 9 from Cyberspace: The Implications of the Internet for Personality and Social Psychology. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 75, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Problematic Internet Use and Psychosocial Well-Being: Development of a Theory-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Measurement Instrument. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002, 18, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.A.; McKenna, K.Y.A.; Fitzsimmons, G.M. Can You See the Real Me? Activation and Expression of the “True Self” on the Internet. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Green, A.S.; Gleason, M.E.J. Relationship Formation on the Internet: What’s the Big Attraction? J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morahan-Martin, J.; Schumacher, P. Incidence and Correlates of Pathological Internet Use among College Students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2000, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, P.M. The Psychology of the Internet; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, J.B. Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal Interaction. Commun. Res. 1996, 23, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, A.L.; Wood, J.V. When Social Networking Is Not Working: Individuals with Low Self-Esteem Recognize but Do Not Reap the Benefits of Self-Disclosure on Facebook. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbaugh, E.E.; Ferris, A.L. Facebook Self-Disclosure: Examining the Role of Traits, Social Cohesion, and Motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W. Neuroticism, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Sutton, S.K.; Ketelaar, T. Relations between Affect and Personality: Support for the Affect-Level and Affective-Reactivity Views. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Negative Affectivity: The Disposition to Experience Aversive Emotional States. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 96, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tackett, J.L.; Lahey, B.B. Neuroticism. In The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model; Widiger, T.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roulin, N. The Influence of Employers’ Use of Social Networking Websites in Selection, Online Self-promotion, and Personality on the Likelihood of Faux Pas Postings. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2014, 22, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.R.; Sung, Y.; Lee, J.A.; Choi, S.M. Get behind My Selfies: The Big Five Traits and Social Networking Behaviors through Selfies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 109, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L.; Camerini, A.L.; Schulz, P.J. Neuroticism in the Digital Age: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Ryan, T.; Kuljus, J.K.; Täht, K.; Scott, G.G. Social Comparison Orientation Mediates the Relationship between Neuroticism and Passive Facebook Use. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.; Abeles, P.; Smith, I.C. Online Social Networking and Psychological Experiences: The Perceptions of Young People with Mental Health Difficulties. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Primi, C.; Casale, S. Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Italian Sample. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P. Short and Extra-Short Forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J. Res. Personal. 2017, 68, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Meas. Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Prezza, M.; Trombaccia, F.R.; Armento, L. La Scala Dell’autostima Di Rosenberg: Traduzione E Validazione Italiana; Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Florence, Italy, 1997; Volume 223, pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sica, C.; Musoni, I.; Bisi, B.; Lolli, V.; Sighinolfi, E.C. Social phobia scale e social interaction anxiety scale: Traduzione e adattamento italiano. Boll. Di Psicol. Appl. 2007, 252, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Mattick, R.P.; Clarke, J.C. Development and Validation of Measures of Social Phobia Scrutiny Fear and Social Interaction Anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998, 36, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.C.; Berg, J.H.; Archer, R.L. Openers: Individuals Who Elicit Intimate Self-Disclosure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, G.D. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, M.P. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sage Focus Ed. 1993, 154, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, B. What You Don’t Know Won’t Hurt Me: Impression Management Functions of Communication Channels in Relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 2000, 26, 403–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, L.M.; Pearce, K.J.; Rubin, R.B. Internet and Face-to-face Communication: Not Functional Alternatives. Commun. Q. 1998, 46, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Choi, S.; Choi, M.; Rho, J. Why People Use Twitter: Social Conformity and Social Value Perspectives. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M. Tweet This: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective on How Active Twitter Use Gratifies a Need to Connect with Others. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Precursors and Underlying Processes of Adolescents’ Online Self-Disclosure: Developing and Testing an “Internet-Attribute-Perception” Model. Media Psychol. 2007, 10, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, A.; Scheithauer, H. The Long-Term Benefits of Positive Self-Presentation via Profile Pictures, Number of Friends and the Initiation of Relationships on Facebook for Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and the Initiation of Offline Relationships. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.A.; Rose, J.P.; Crane, C. Transformation Tuesday”: Temporal context and post valence influence the provision of social support on social media. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 158, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Hancock, J.T. Self-Disclosure and Social Media: Motivations, Mechanisms and Psychological Well-Being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 31, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco Pernice, A.; Cavallone, M. Le Ricerche Di Mercato e Di Marketing: L’indagine Stetoscopio. In Le Ricerche di Mercato e di Marketing; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H. Social Media Use and Well-Being. In Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 73.5% |

| Homosexual | 5.4% |

| Bisexual | 15.2% |

| Other | 5.5% |

| Employment status | |

| Student | 47.4% |

| Employee | 28.4% |

| Self-employed | 10% |

| Unemployed | 11.6% |

| Running a household | 2% |

| Retiree | 0.5% |

| Practice | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| 1. Reblogging visual content (photos, gifts, pictures, etc.) | 3.8 (1.3) |

| 2. Sharing/collecting quotes or aphorisms | 3.3 (1.3) |

| 3. Writing text posts in the form of a personal diary, stories, etc. | 3.2 (1.5) |

| 4. Sharing/posting content regarding one or more fandoms (TV series/books/actors etc.) or a specific topic (reading, food, animals, etc.) | 3.0 (1.3) |

| 5. Knowing/interacting with other users with similar interests | 2.6 (1.1) |

| 6. Publishing one’s own graphic contents (photographs, illustrations cartoons, graphic work, etc.) | 2.4 (1.3) |

| 7. Sharing erotic and/or sexual materials | 1.9 (1.2) |

| 8. Sharing and/or commenting on news | 1.9 (1.0) |

| 9. Collecting content from other social networks | 1.9 (1.1) |

| 10. Interacting with friends you know even offline | 1.9 (1.2) |

| 11. Sharing your knowledge in a specific knowledge field (scientific dissemination) | 1.8 (1.0) |

| 12. Advertising your brand or your work | 1.2 (0.7) |

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Self-esteem | 2.64 (0.7) | 1 | |||||

| 2 Social anxiety | 1.87 (0.9) | −0.64 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3 Negative emotionality | 3.50 (1.0) | −0.70 ** | 0.60 ** | 1 | |||

| 4 POSI | 2.97 (1.5) | −0.37 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | ||

| 5 Self-disclosure Tumblr | 1.62 (1.0) | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.10 * | 1 | |

| 6 Self-disclosure other SNS | 0.58 (0.7) | 0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.01 | 0.28 ** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bianchi, M.; Fabbricatore, R.; Caso, D. Tumblr Facts: Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 1257-1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090087

Bianchi M, Fabbricatore R, Caso D. Tumblr Facts: Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2022; 12(9):1257-1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090087

Chicago/Turabian StyleBianchi, Marcella, Rosa Fabbricatore, and Daniela Caso. 2022. "Tumblr Facts: Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 12, no. 9: 1257-1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090087

APA StyleBianchi, M., Fabbricatore, R., & Caso, D. (2022). Tumblr Facts: Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12(9), 1257-1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090087