Exploring Issues and Challenges of Leadership among Early Career Doctors in Nigeria Using a Mixed-Method Approach: CHARTING Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nature of the Study

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. FGD

2.2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. FGD

2.3.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. FGD

Socio-Demographic Data of Respondents

3.2. Thematic Findings

3.2.1. Inborn Quality and Bestowed Responsibility

“There is this saying that it is either you are born great, you achieve greatness or greatness was entrusted on you so for some of us greatness or been leaders was entrusted on some of us, we had no choice in the matter” (R7).

3.2.2. Passion to Make a Notable Change

“I will say it is a passion to see things change, I will call it in summary a paradigm shift. It is better that you are an actor than you are actually watching the screen” (R5).

“For elective leadership positions personally just like every other member I discovered that prior to when I started aspiring for positions, I once looked at my leaders and discovered that they’ve not been doing enough and so there was this drive that ok if sometimes if things are glaring that needs change but you discover that the change is not coming so there is this drive probably if you are viewing it in this way why not take up the position and effect that change. So the desire for change drives for obtaining a leadership elective positions” (R3).

“The practicality of leadership actually comes when you are immersed in the leadership role itself, and that comes better when you are a senior registrar, or you are a consultant" (R8).

“The yearning for you to be a leader is to make an impact; impact in your association, impact in the wider body of NARD, impact even in your department” (R1).

“The reason why we want to go into this leadership position is because we are sick and tired of other people making the laws for us" "People that understand the intricacies of medical ethics should go in there and effect the change, and those people that are outside will come back to this country that is what I glamour for” (R5).

3.2.3. Challenging Experiences

“I think leadership role in this environment is not easy because it is like a car that is not working and you are trying to jump-start so you tend to put in a lot of energy to drive that car, so you tend to burn out a lot, so it is not easy been a leader in a system that is not working because you tend to put in a lot much more to see things work. It is quite challenging I must say” (R5).

“I remember in my department while we started having good pass rate was when our chief resident stood that no (no-no) when you are doing exams don’t come to the clinic and the consultant fought, and she stood her ground that it’s not happening and after that our result dramatically changed and when the consultants saw that the result has changed they backed down, so that is the foremost is to make impact that is why we are going for leadership positions” (R1).

“I’m part of the welfare unit in my department, and over time we found out that all we do is contribute into the welfare purse without been internalising it. We don’t feel the effect of our contribution. We found out that most of the things we do and the money we pay are been used for other things. We are using it for patient welfare like non-indigent patients, we are using it to repair this one and repair that one but into us as doctors we were not feeling the welfare. So we came together, and we told our HOD that we will not use our monies again, let’s use it for ourselves first. Our oath says we should first take care of our health. In taking care of ourselves and that drastically changed our work environment, you know when you are on calls you are calmer because the call rooms are better, well-equipped, ACs, refrigerators and all that. We did all that for our call rooms because definitely management does not go there, all they do is cleaning and they only most times focused on patient’s care, not on doctor’s care. So we had to take into consideration ourselves, and we made an impact. After that our calls has been better and our work experience even with the way we work changed because we were now taking care of ourselves, so that caused an impact in our output towards the patient” (R4).

3.2.4. Communication Skills

“First is communication, your ability to communicate not to order but to communicate. To be a communicator, to be able to pass across a message and the message is understood, and the instructions carried out. You are not an instructor, and you are not an enforcer" “Then you also have to have integrity in carrying out your own duties. Assuming you expect your residents to be at work at 7:30, you should be at work at 7:00 so when you show that form of integrity and diligence you are easily followed (you understand) for instance, we have a chief resident who…before you get there she is there, and she does not shout or scream or rain abuses or melt out punishment just because you know that she will get there before you, you have to get there before her (you understand) because that is her attitude of integrity, punctuality of being nice and humble so everybody started going that way” (R4).

3.2.5. Listening and Decision-Making Skills

“A leader has to be a good listener” “A leader has to be a good decision maker because a lot of decision would impact on the welfare of the people the person so if he doesn’t know how to be a good decision maker it would impact negatively on the team” (R1).

“A leader has to be (how will I put it) firm when you make decisions you have to stick to them” (R1).

3.2.6. Integrity and Being Unbiased

“A good leader in the health sector is to be professionally unbiased” “A good leader of a health sector, if you are a doctor and a leader you should know that you are not only handling the affairs of doctors; there are other professionals among them; the nurses are there, even the health attendants are there, so don’t be biased if a doctor is faulty; tell him and handle that situation as such not because you are a doctor and you start compromising your leadership skills it won’t augur well. So a good leader must be professionally unbiased, and that is the only way that other professionals in the health sector will come to respect that leader” (R5).

3.2.7. Curriculum Review

“I think as part of our curriculum from the medical school; leadership should be inculcated because as medical doctors by virtue of that our position we are already leaders somehow (you know) and it is so bad that you will see doctors occupy leadership position and perform very woefully so I think it should be part of the curriculum while we are medical students they should be taught leadership so going forward when you become a doctor it will become part and parcel of you which you can always want to exercise good leadership skills (you know) that is my take on it” (R5).

3.3. Questionnaire Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Focus Group Discussion Guide

| S/No. | Questions | Probes |

| 1. | How would you describe residency training generally? | Who are those eligible for the training? Criteria used in selection? Views regarding residency duties? Do you think residency training helps with research? |

| 2. | What do you think about leadership? | What is your motivation to take (non-elective) or contest (elective) for leadership position? Attitude and general disposition to leadership skills Experience and perception to leadership position in medical and clinical settings Types of leadership skills Frequency of training |

| 3. | What are the challenges of leadership among ECDs? | |

| 4. | What would you suggest or recommend to mitigate leadership challenge among early career doctors (ECDs)? |

References

- Ojo, E.; Chirdan, O.O.; Ajape, A.A.; Agbo, S.; Oguntola, A.S.; Adejumo, A.A.; Babayo, U.D. Post-graduate surgical training in Nigeria: The trainees’ perspective. Niger. Med J. J Niger. Med Assoc. 2014, 55, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, T.O.; Akinwumi, A.F. Doctors as managers of healthcare resources in Nigeria: Evolving roles and current challenges. Niger. Med. J. 2015, 56, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbulut, Y.; Esatoglu, A.E.; Yildirim, T. Managerial roles of physicians in the Turkish healthcare system: Current situation and future challenges. J. Health Manag. 2010, 12, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltart, C.E.; Cheung, R.; Ardolino, A.; Bray, B.; Rocos, B.; Bailey, A.; Bethune, R.; Butler, J.; Docherty, M.; Drysdale, K.; et al. Leadership development for early career doctors. Lancet 2012, 379, 1847–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetui, M.; Hurtig, A.K.; Ekirpa-Kiracho, E.; Kiwanuka, S.N.; Coe, A.B. Building a competent health manager at district level: A grounded theory study from Eastern Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witman, Y.; Smid, G.A.C.; Meurs, P.L.; Willems, D.L. Doctors in the lead: Balancing between two worlds. Organization 2010, 18, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, D.N.; Jenny, C. Barriers to doctors successfully delivering leadership in the NHS. Future Hosp. J. 2016, 3, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.; Neale, G. Clinical leadership in the provision of hospital care. BMJ 2005, 330, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, J.K.; Amanda, G.; Baker, A. Why The Best Hospitals Are Managed by Doctors. Harvard Business Review. 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals-are-managed-by-doctors (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Anyaehie, U.; Anyaehie, U.; Nwadinigwe, C.; Emegoakor, C.; Ogbu, V. Surgical resident doctor’s perspective of their training in the Southeast. region of Nigeria. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, O.; Ogunsuji, O.; Olaopa, O.; Kpuduwei, S.; Efuntoye, O.; Fagbule, F.O.; Aigbomian, E.; Ibiyo, M.; Buowari, D.Y.; Wasinda, U.F.; et al. Trainees Collaboratively Investigating Early Career Doctors’ Themes: A NARD Initiative in Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2019, 28, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmodi, K.; Ekudayo, O.; Adebayo, O.; Efuntoye, O.; Ogunsuji, O.; Ibiyo, M.; Tanimowo, A.; Buowari, D.Y.; Ibrahim, Y.A.; Grillo, E.; et al. Challenges of residency training and early career doctors in Nigeria study (CHARTING STUDY): A protocol paper. Niger. J. Med. 2019, 28, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Igbokwe, M.; Babalola, I.; Adebayo, O. CHARTING Study: A Trainee Collaborative Research Study. J. Dr. Netw. Newsl. 2019, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Adeloye, D.; David, R.A.; Olaogun A., A.; Auta, A.; Adesokan, A.; Gadanya, M.; Opele, J.K.; Owagbemi, O.; Iseolorunkanmi, A. Health workforce and governance: The crisis in Nigeria. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlearney, A.S. Leadership development in healthcare: A qual-itative study. J. Organiz. Behav. 2006, 27, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, R.A.; Williams, P.D.; Seashore, C.N. Chief resident training: Developing leadership skills for future medical leaders. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1991, 145, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur L., M. Medical leaders wanted-business degree desirable. Phys. Exec. 2009, 35, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Olumide, A. Fundamentals of Health Service Management for Doctors and Senior Health Workers in Africa; Kemta Publishers: Ibadan, Nigeria, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Centre | Geo-Political Zone | Target Population | Sample | % of n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMC, Abeokuta | South-West | 387 | 116 | 24.9 |

| UCH, Ibadan | South-West | 531 | 170 | 35.9 |

| FTH, Ido Ekiti | South-West | 194 | 72 | 15.2 |

| JUTH, Jos | North-Central | 504 | 17 | 3.6 |

| FMC, Katsina | North-West | 150 | 46 | 9.7 |

| LAUTECH TH, Ogbomosho | South-West | 89 | 36 | 7.6 |

| UPTH, Port-Harcourt | South-South | 460 | 17 | 3.6 |

| Total | All zones | 2315 | 474 | 100.0 |

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 319 (67.3) |

| Female | 155 (32.7) |

| No response | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (Years) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 33.5 (±5.7) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 176 (36.1) |

| Married | 296 (62.4) |

| Divorced | 4 (0.8) |

| No response | 3 (0.6) |

| Cadre | |

| House officer | 109 (23.0) |

| Medical officer | 37 (7.8) |

| Registrar | 171 (36.1) |

| Senior registrar | 146 (30.8) |

| No response | 11 (2.3) |

| Number of Years after Bagging Medical/Dental Degree * | |

| Mean (±SD) | 7.2 (±4.1) |

| Years of Practice | |

| Mean (±SD) | 6.9 (±3.8) |

| Years Spent in Current Job Position | |

| Mean (±SD) | 3.3 (±2.7) |

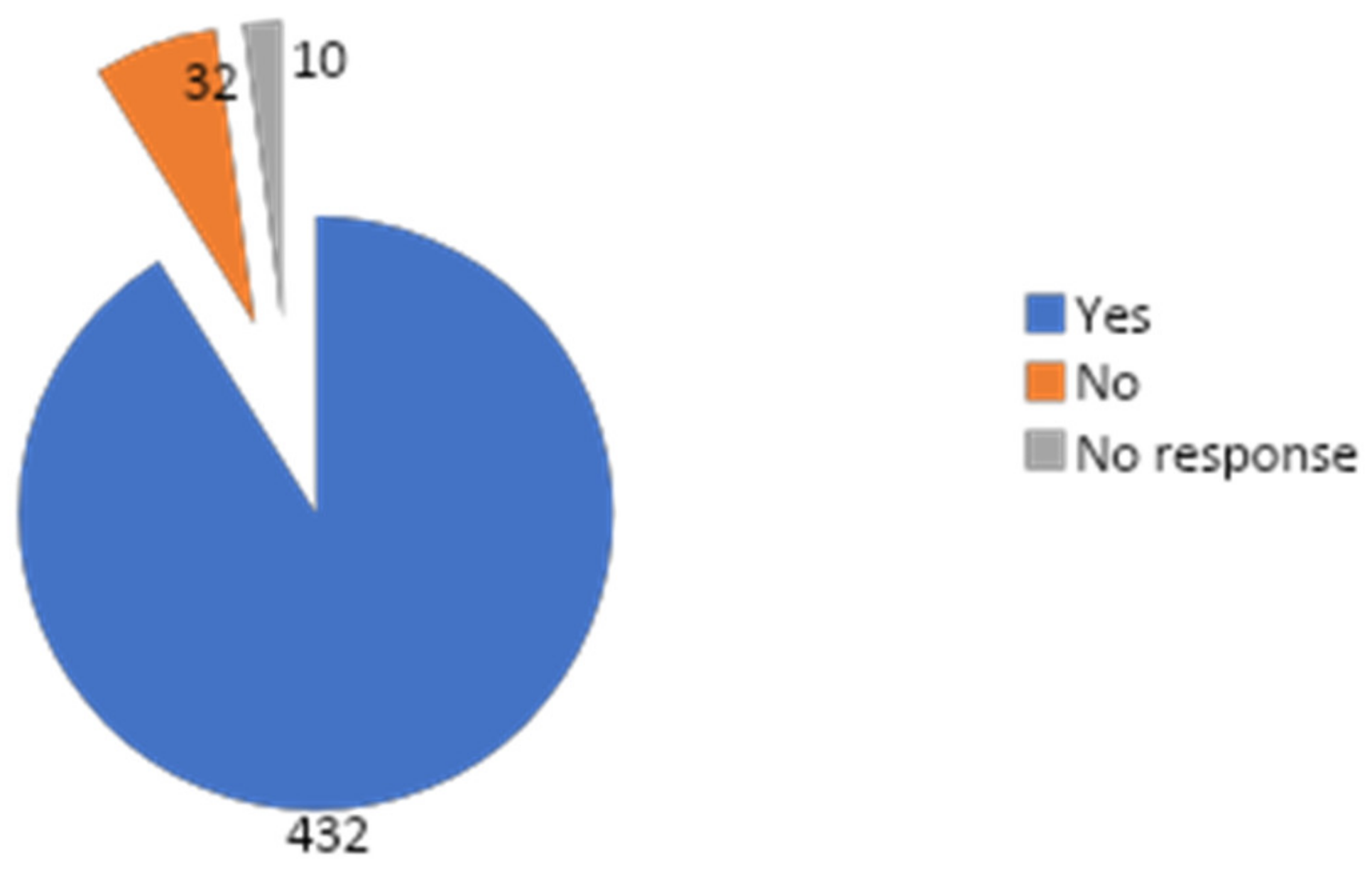

| Cadre | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| House officer | 94 (21.8) |

| Medical officer | 33 (7.6) |

| Junior registrar | 157 (36.3) |

| Senior registrar | 139 (32.2) |

| Unspecified | 9 (2.1) |

| Total * | 432 (100.0) |

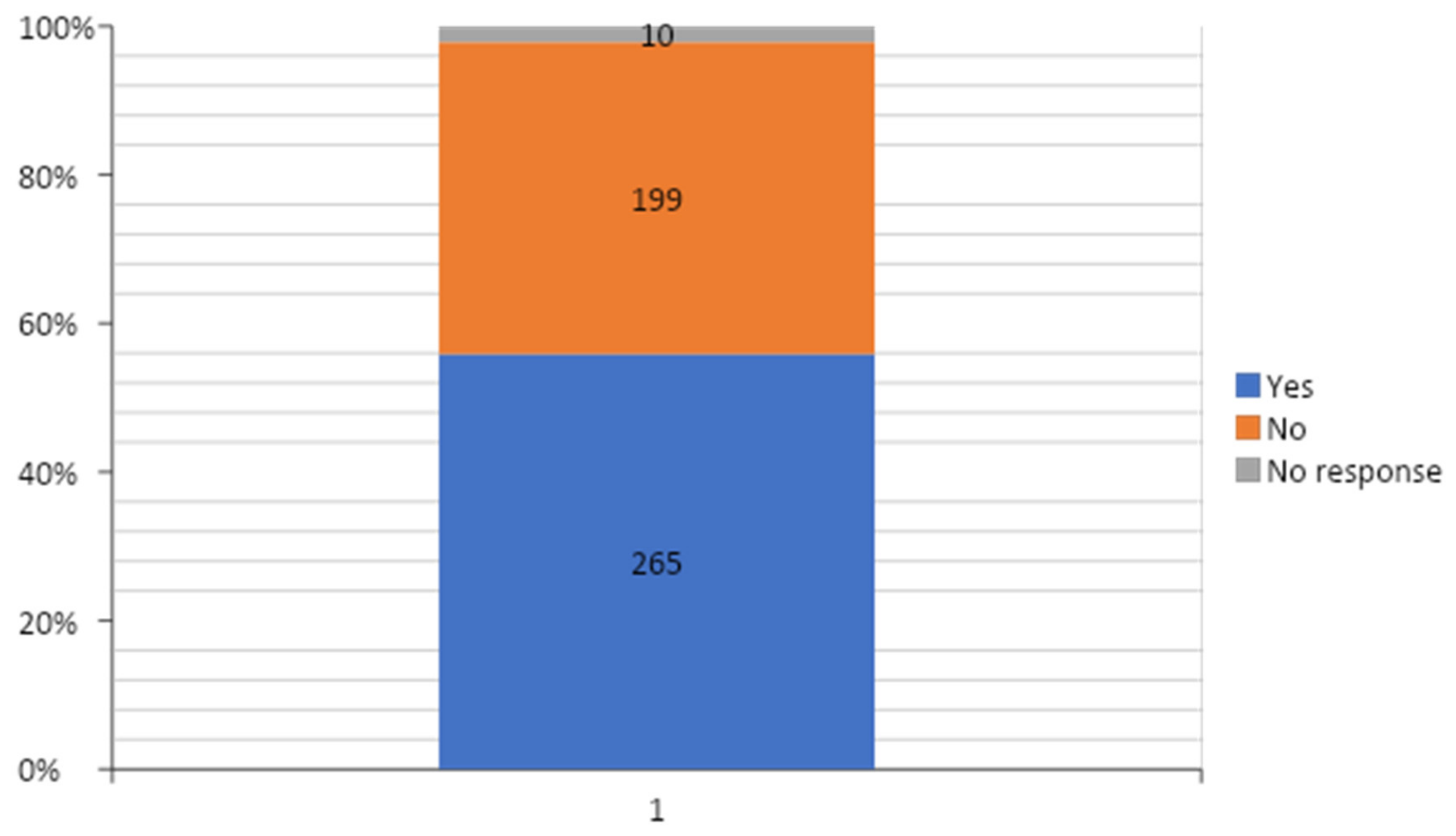

| Period | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| In medical school | 101 (38.1) |

| During internship | 37 (13.9) |

| During junior residency | 49 (18.5) |

| At senior residency | 33 (12.5) |

| Others | 32 (12.1) |

| No response | 13 (4.9) |

| Total * | 265 (100.0) |

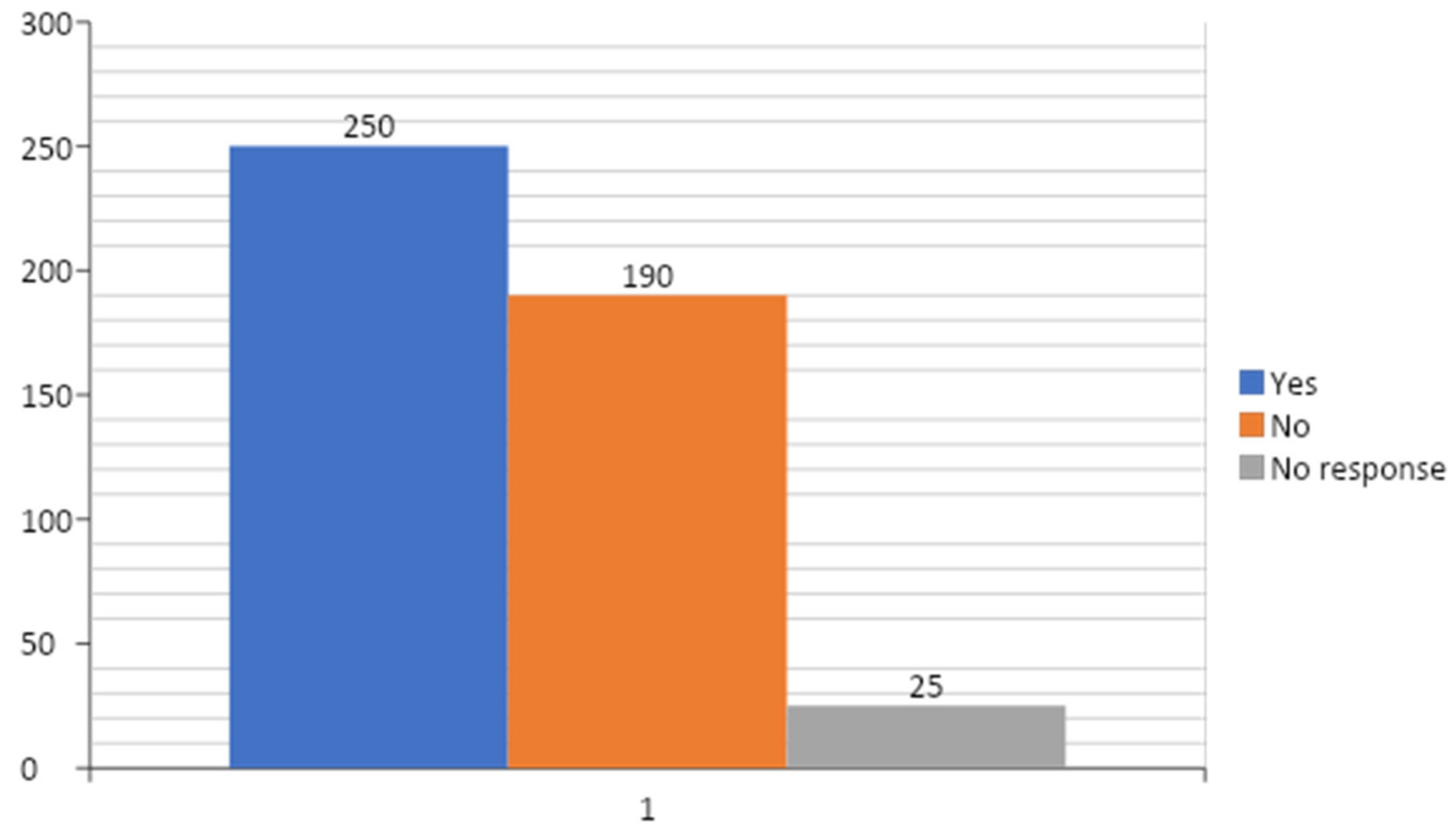

| Challenges (N = 250) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Lack of training experience | 59 (23.6) |

| Lack of confidence | 23 (9.2) |

| Lack of support from fellow trainees | 75 (30.0) |

| Lack of support from senior doctors | 53 (21.2) |

| Lack of understanding from other members of the management team | 92 (36.8) |

| Lack of support from management | 51 (20.4) |

| Source of Support | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Management | 37 (14.8) |

| Senior colleague(s) | 80 (32.0) |

| Fellow trainee | 82 (32.8) |

| Other members of the management team (non-doctors) | 23 (9.2) |

| Do You Consider Leadership and Management Skills Important for Doctors? * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | p-value | ||

| Have you ever received leadership and management training? * | Yes | 248 | 14 | 262 | 0.118 |

| No | 180 | 18 | 198 | ||

| Total | 428 | 32 | 460 | ||

| Do you consider your medical training so far sufficient to carry out good leadership and management role? * | Yes | 102 | 7 | 109 | 0.954 |

| No | 314 | 21 | 335 | ||

| Total | 416 | 28 | 444 | ||

| Have you ever had the opportunity to assume the leadership role in your medical practice, so far? * | Yes | 238 | 18 | 256 | 0.609 |

| No | 178 | 11 | 189 | ||

| Total | 416 | 29 | 445 | ||

| What cadre of doctors require leadership and management skills? * | House officer | 7 | 13 | 20 | 0.028 |

| Medical officer | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Junior registrar | 0 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Senior registrar | 0 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Have you ever been queried for exhibiting poor leadership and management skills? * | Yes | 62 | 5 | 67 | 0.720 |

| No | 328 | 22 | 350 | ||

| Total | 390 | 27 | 417 | ||

| Should leadership and management skill acquisition programmes be part of the medical training programme in Nigeria? * | Yes | 408 | 25 | 433 | <0.0001 |

| No | 17 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Total | 425 | 32 | 32 | ||

| What is your preferred source of acquiring leadership and management skills? * | Rotations/outside postings for management courses | 227 | 10 | 237 | 0.011 |

| At the yearly college update courses | 67 | 11 | 78 | ||

| At the daily departmental trainer–trainee encounter | 118 | 9 | 127 | ||

| Total | 412 | 30 | 442 | ||

| What is your preferred mode of acquiring leadership and management skills? * | Online lectures/webinars | 81 | 9 | 90 | 0.066 |

| Short classroom lectures | 152 | 16 | 168 | ||

| Case method | 78 | 3 | 81 | ||

| Role-playing method | 104 | 3 | 107 | ||

| Total | 415 | 31 | 446 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isibor, E.; Kanmodi, K.; Adebayo, O.; Olaopa, O.; Igbokwe, M.; Adufe, I.; Oduyemi, I.; Adeniyi, M.A.; Oiwoh, S.O.; Omololu, A.; et al. Exploring Issues and Challenges of Leadership among Early Career Doctors in Nigeria Using a Mixed-Method Approach: CHARTING Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 441-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010033

Isibor E, Kanmodi K, Adebayo O, Olaopa O, Igbokwe M, Adufe I, Oduyemi I, Adeniyi MA, Oiwoh SO, Omololu A, et al. Exploring Issues and Challenges of Leadership among Early Career Doctors in Nigeria Using a Mixed-Method Approach: CHARTING Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2020; 10(1):441-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsibor, Efosa, Kehinde Kanmodi, Oladimeji Adebayo, Olusegun Olaopa, Martin Igbokwe, Iyanu Adufe, Ibiyemi Oduyemi, Makinde Adebayo Adeniyi, Sebastine Oseghae Oiwoh, Ayanfe Omololu, and et al. 2020. "Exploring Issues and Challenges of Leadership among Early Career Doctors in Nigeria Using a Mixed-Method Approach: CHARTING Study" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 10, no. 1: 441-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010033

APA StyleIsibor, E., Kanmodi, K., Adebayo, O., Olaopa, O., Igbokwe, M., Adufe, I., Oduyemi, I., Adeniyi, M. A., Oiwoh, S. O., Omololu, A., Egbuchulem, I. K., Kpuduwei, S. P. K., Efuntoye, O., Egwu, O., Ogunsuji, O., Grillo, E. O., & Rereloluwa, B., on behalf of CHARTING investigators. (2020). Exploring Issues and Challenges of Leadership among Early Career Doctors in Nigeria Using a Mixed-Method Approach: CHARTING Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 441-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010033