Assessment of Livability in Commercial Streets via Placemaking

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dimension Extraction

2.1.1. First Step (Model Review)

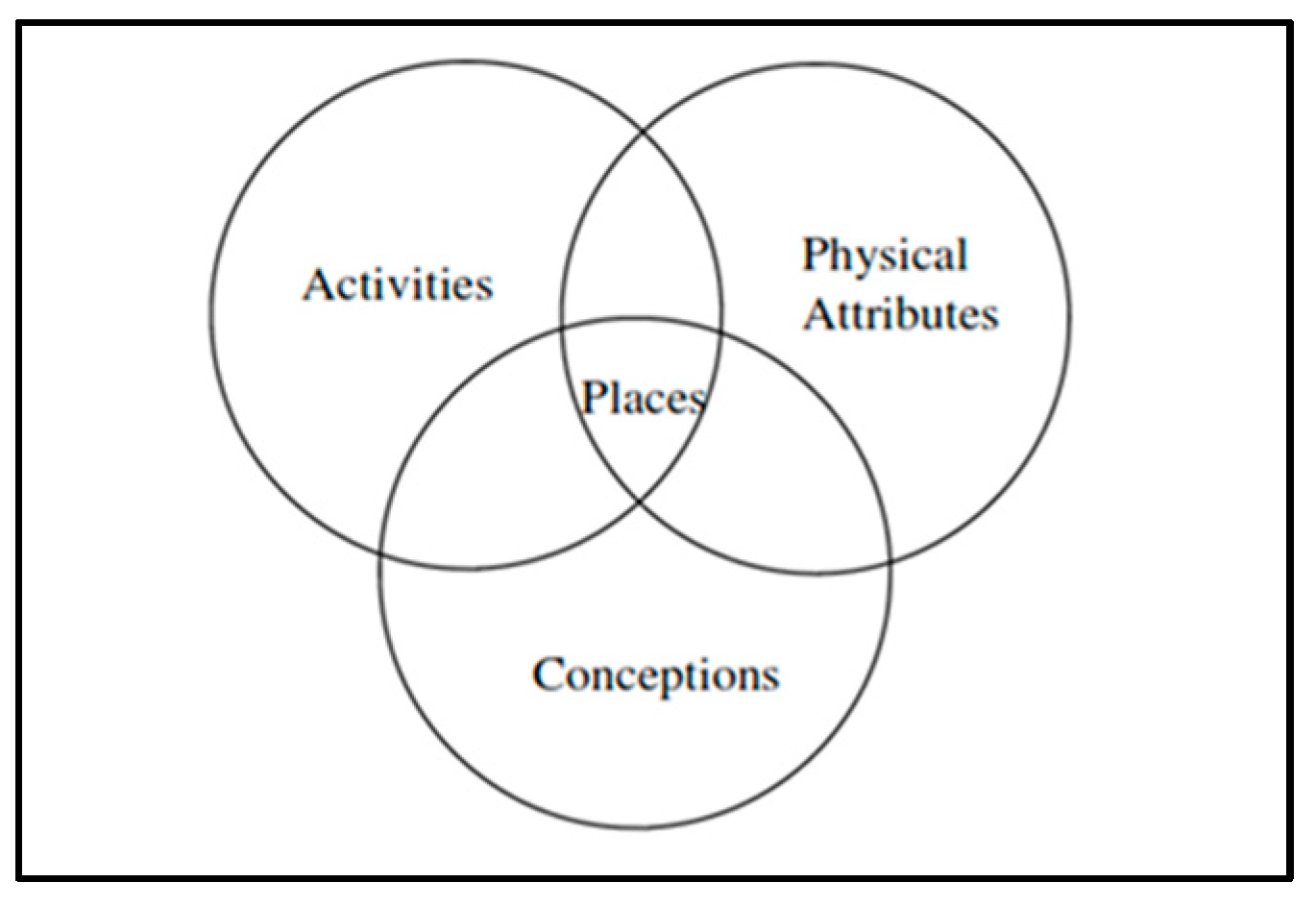

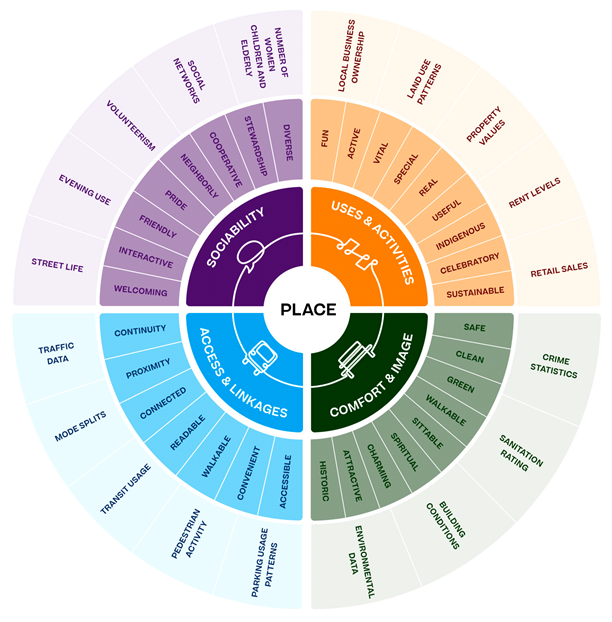

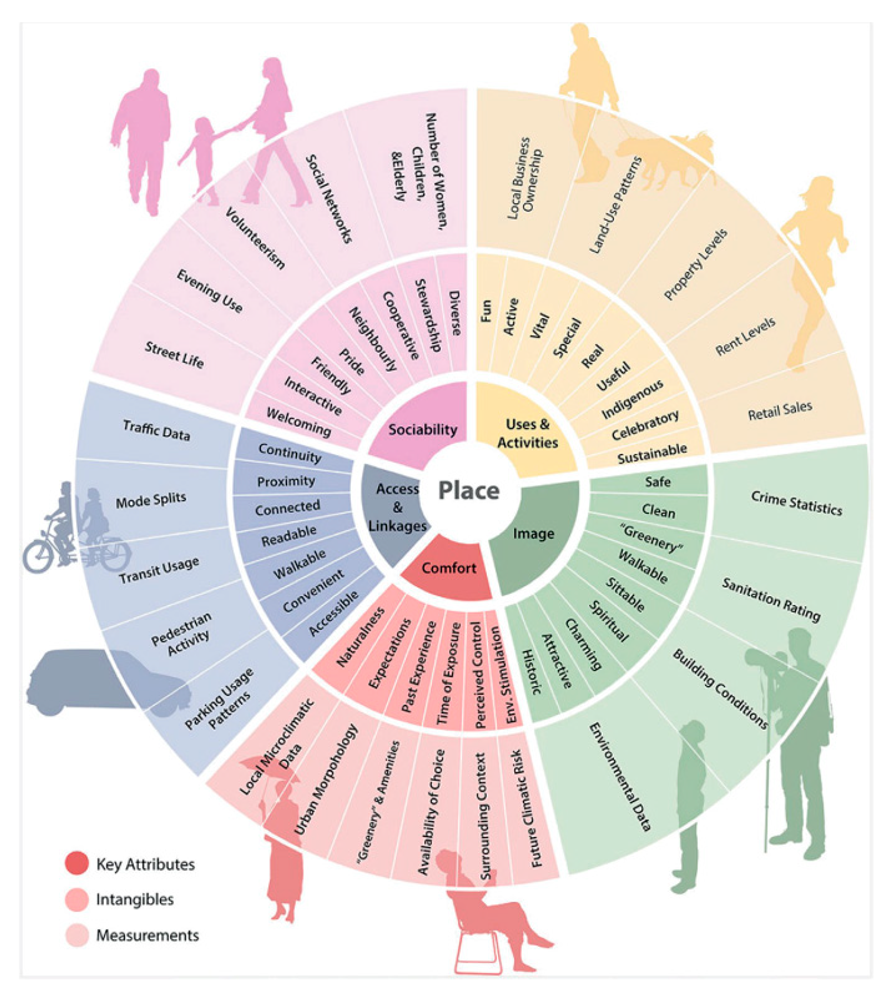

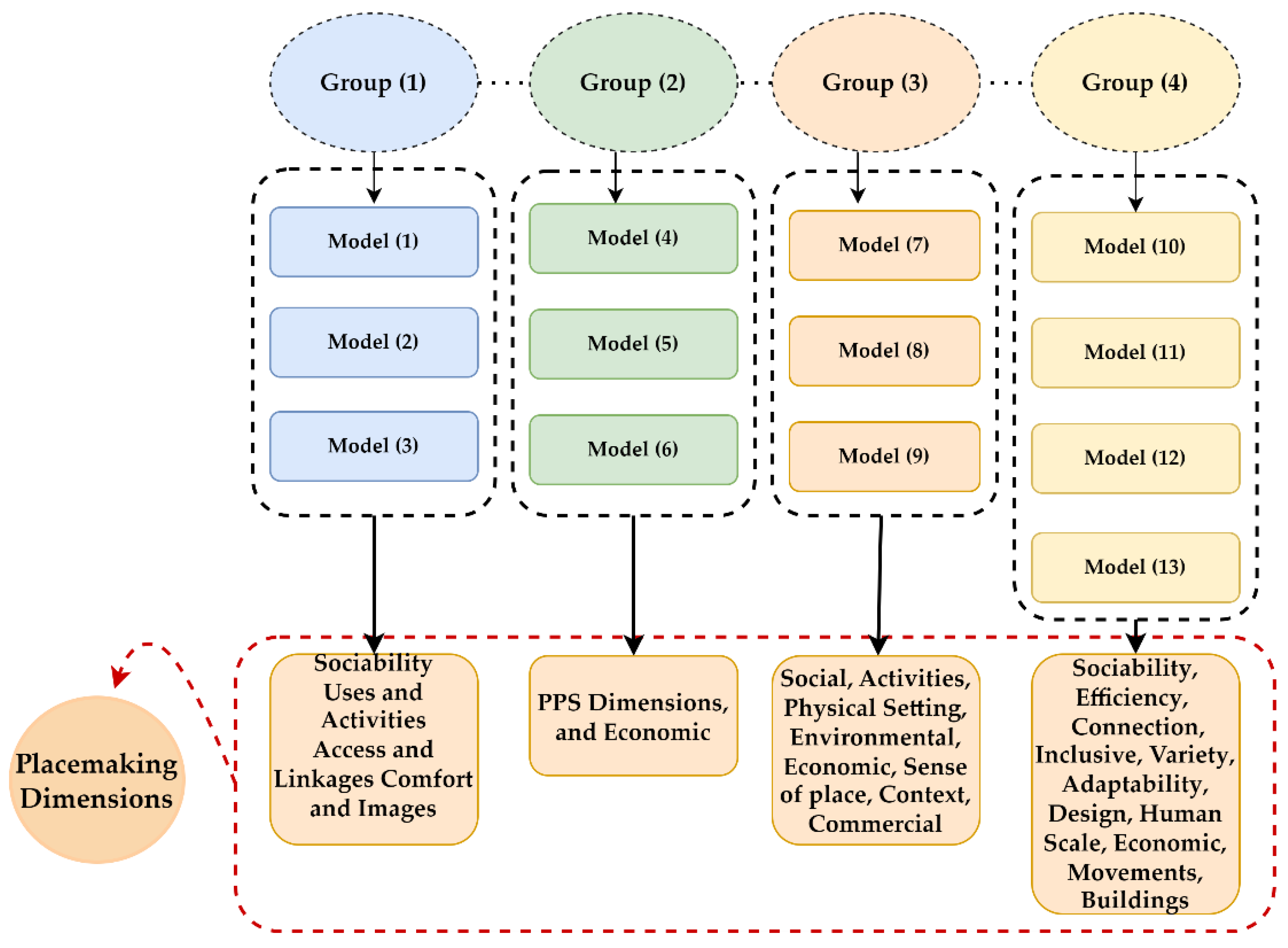

- Thirteen models adopted by researchers, architectural theorists, and urban designers were reviewed to evaluate placemaking on a commercial street. The most frequent dimensions were sociability, accessibility, uses and activities, comfort, and image.

- The dimensions were regrouped into four groups based on the common dimensions among the models, as well as the derivations of the new dimensions among them.

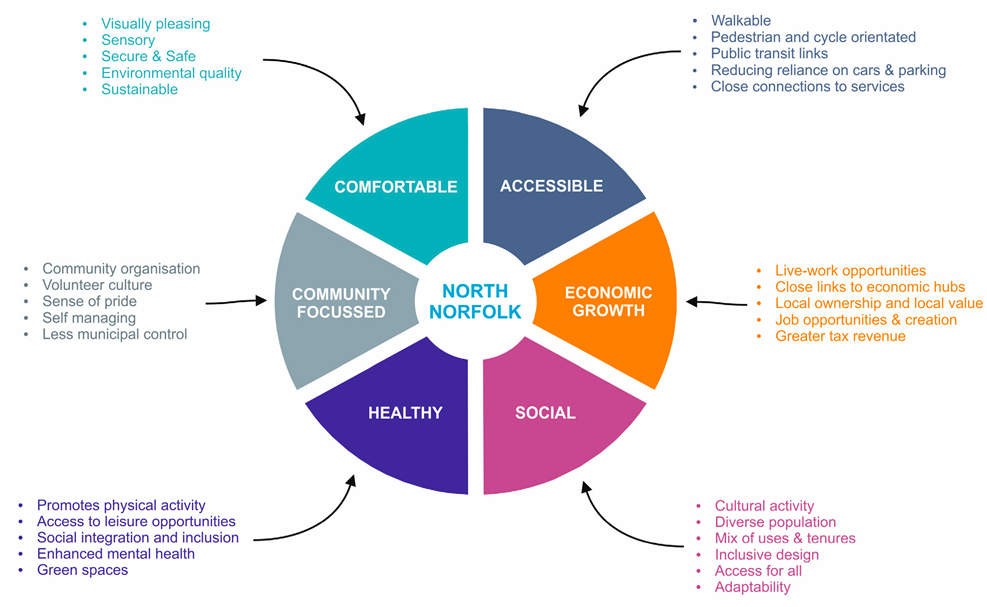

- The second group, with three models, shared the same basic dimensions. Other dimensions were added according to the context of the research sample, site analysis, and conservation, since the selected site was within a conservation area. Both climatic and economic variables were added to the consideration of the selected samples, as shown in Appendix A Table A2 [11,12,13].

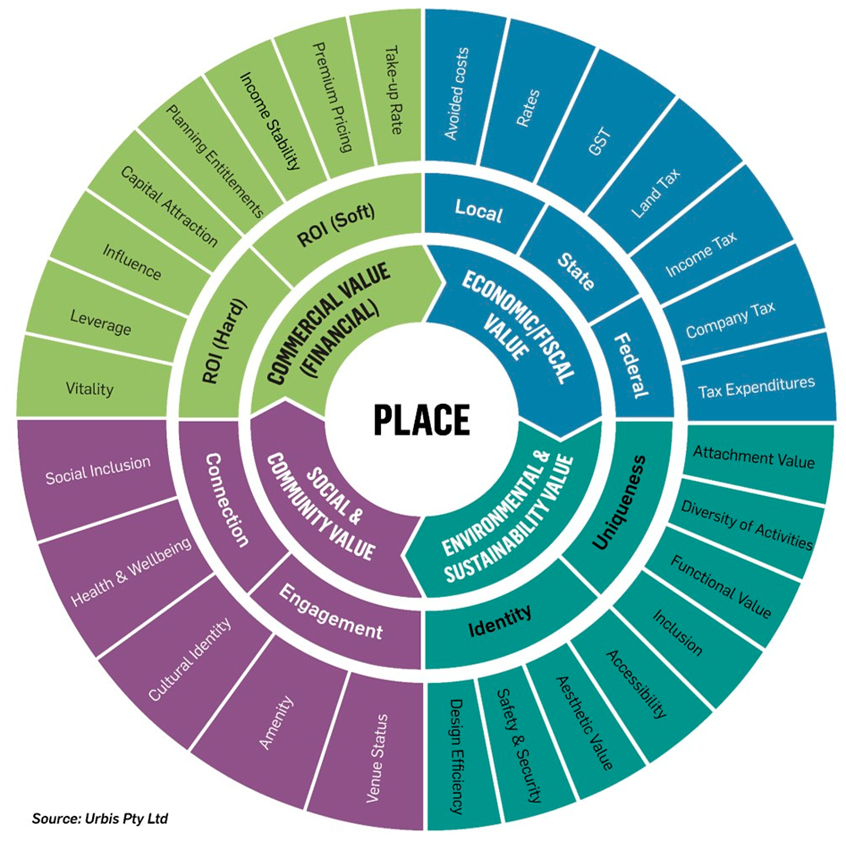

- Three other models added commercial and economic dimensions to the primary model, either implicitly in one of the main dimensions or explicitly, as shown in Appendix A Table A3 [14,15,16].

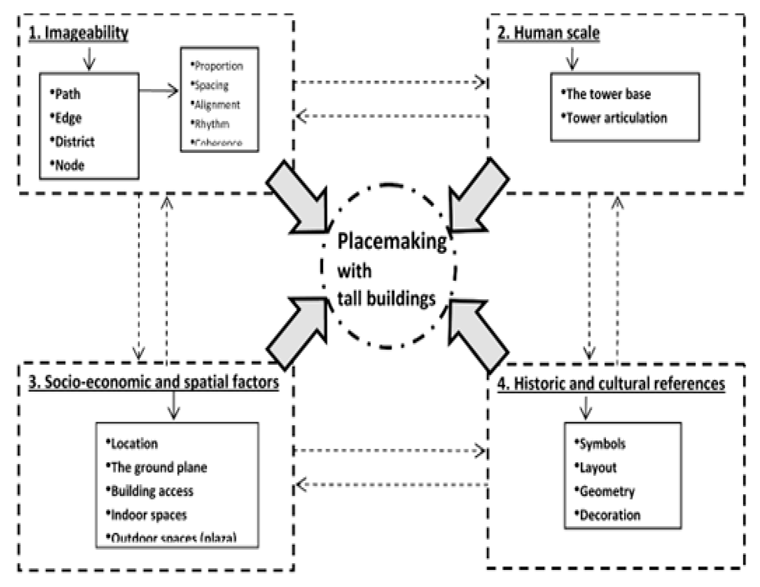

- Dimensions such as design, environment, urban context, history, space, human scale, climate, and sense of place were mentioned individually and according to the research need and problem in this group. Researchers have praised the importance of these dimensions as the basic pillars of placemaking that had not been considered previously, as shown in Appendix A Table A4 [17,18,19,20]. (Please see the compared dimensions table in Appendix A.)

- By comparing the dimensions of the aforementioned models presented by the researchers, an extrapolation was performed to determine the most important and consistent factors to use within the model and the framework, both theoretically and practically.

- The least frequently used dimensions in the previous studies were also included in the theoretical framework. A comprehensive evaluation of placemaking was extracted to evaluate the livability of a commercial street, as shown in Figure 2.

2.1.2. Second Step (The Additional Dimension)

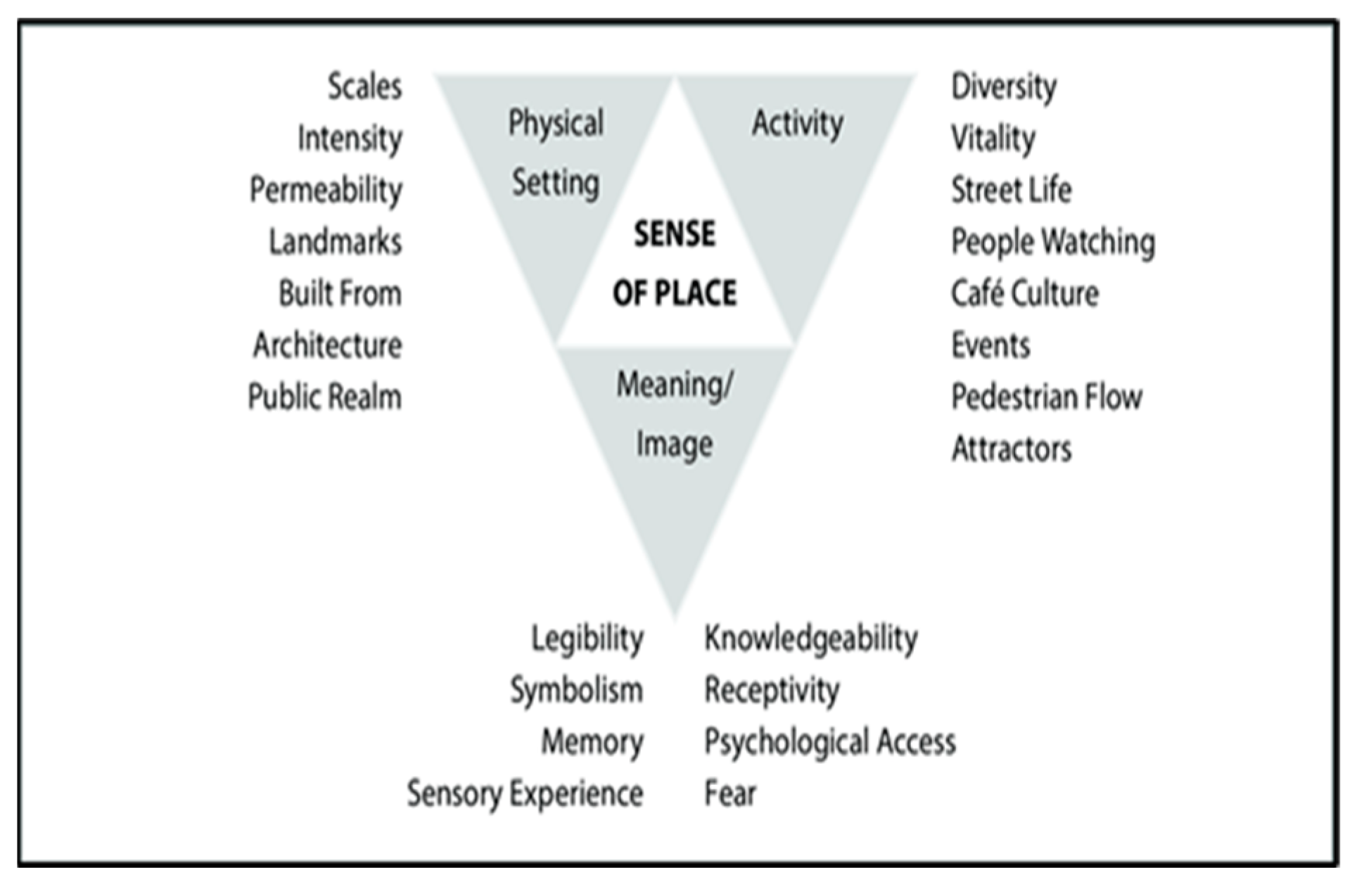

A Sense of Place

A Sense of Place and Placemaking

2.1.3. Third Step (The Theoretical Dimensions)

2.2. Placemaking Model

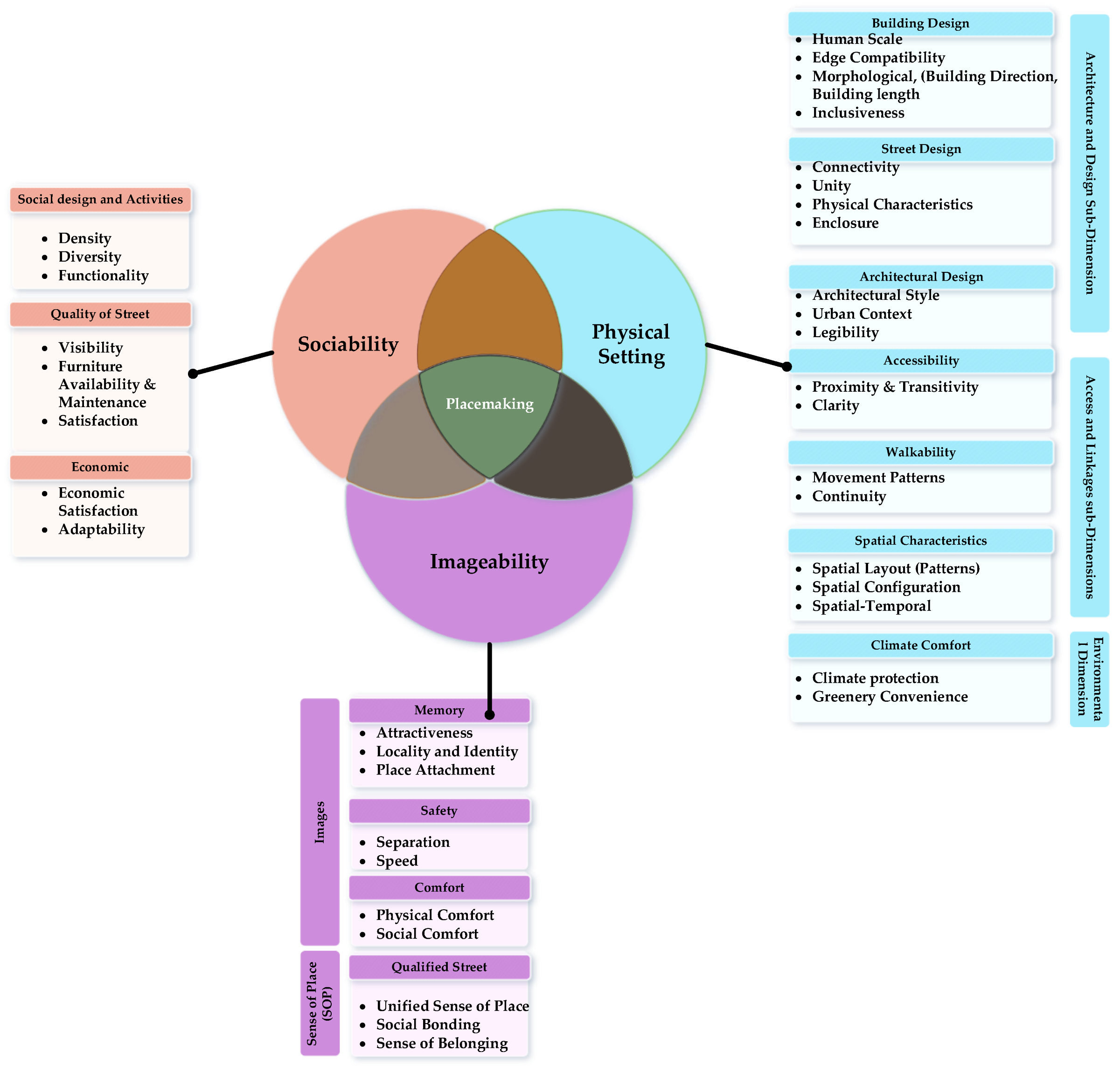

- Dimensions were compared to identify the most influential studies in place and placemaking.

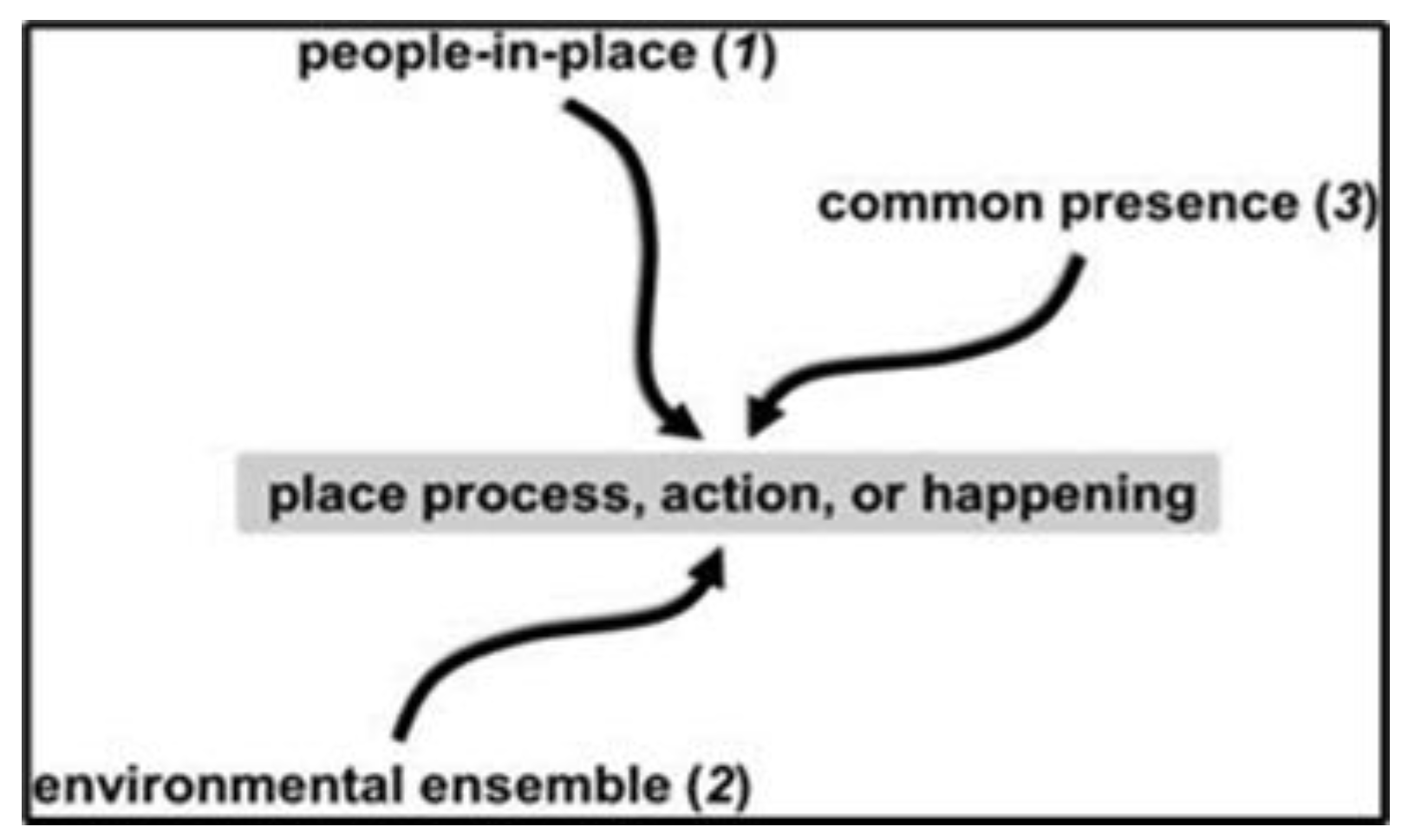

- After reviewing the models and according to previous studies that developed or applied these models, we identified the importance of the four dimensions: sociability; access and linkages; uses and activities; and comfort and image [7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Punter, Canter, Montgomery, Mojgan, and Seamon [36,38,39,40,41] all agreed on the presence of three main dimensions that had could improve the quality of a place: the social aspect, the physical setting, and the meaning or sense of place. After comparing these practical and theoretical aspects, our model was restructured to reflect a local commercial street.

- According to the previous literature, the theoretical framework was reconfigured into a practical framework, consisting of three pillars. Consequently, the organization of these three dimensions was reduced and restructured, as shown in Table 1.

- Our research identified three main dimensions: physical setting, sociability, and image. Each dimension was then subdivided into another secondary dimension, including factors, secondary factors, and possible values, as shown in Figure 11.

- Our research adopted these dimensions and factors as the foundation of the practical framework. The placemaking framework was identified as appropriate for assessing placemaking strategies for commercial streets.

- The practical framework consisted of five sequences, starting with dimensions, sub-dimensions, factors, sub-factors, and possible values, which had detailed descriptions for every factor to identify the best and worst phenomena of the street, and an example is shown in Table 2. For more details, the comprehensive practical framework is available in Appendix B.

2.2.1. Sociability Dimension

2.2.2. Physical Setting Dimension

2.2.3. Familiarity Dimension

2.3. Placemaking Framework

2.4. Study Method

Selecting the Street

- The first stage was to identify several commercial streets as candidates.

- We decided to select connector streets between the circular throughways of Erbil city, as these were categorized as crowded and diverse commercial streets.

- The widths of the selected streets were 20–50 m, and the lengths were 600–2000 m.

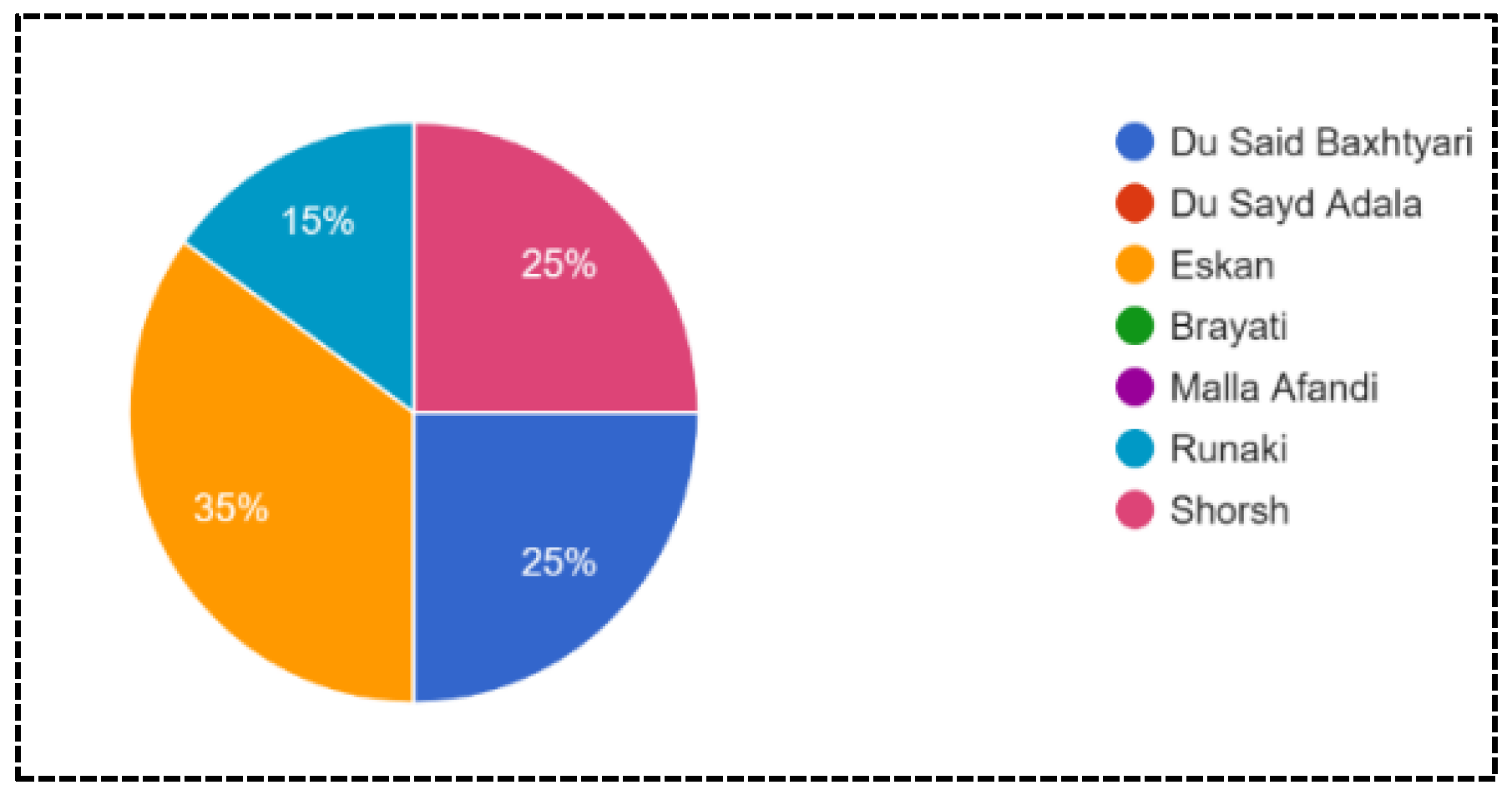

- A rapid pilot survey was conducted to obtain local opinions on the most lively and livable streets, as shown in Figure 13. Of the seven commercial streets, Eskan Street had the highest rate of preference (35%) and was selected as the research object.

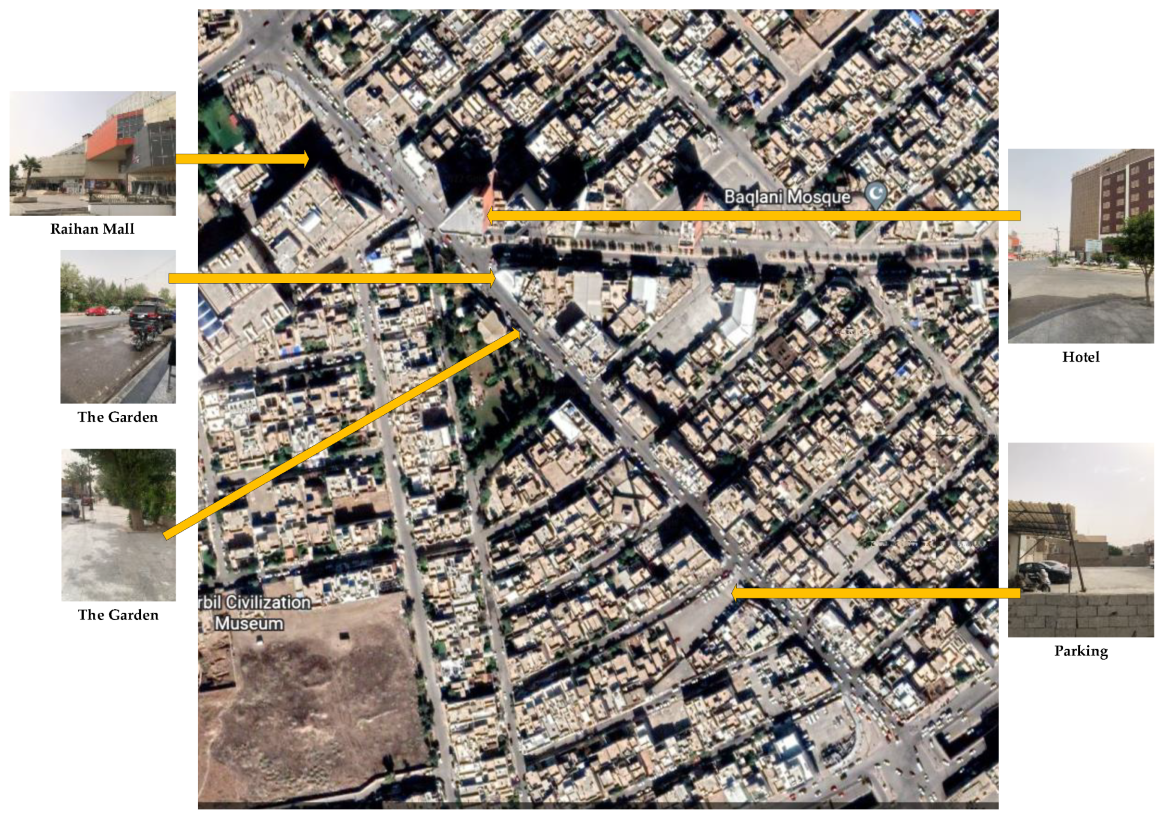

- People identified this street as being multi-functional and diverse, with attraction points, in addition to having two parking areas, as shown in Figure 14.

- Eskan Street was adopted as the research object for the application of our placemaking framework to assess its livability.

2.5. Case Study

2.6. Street Description

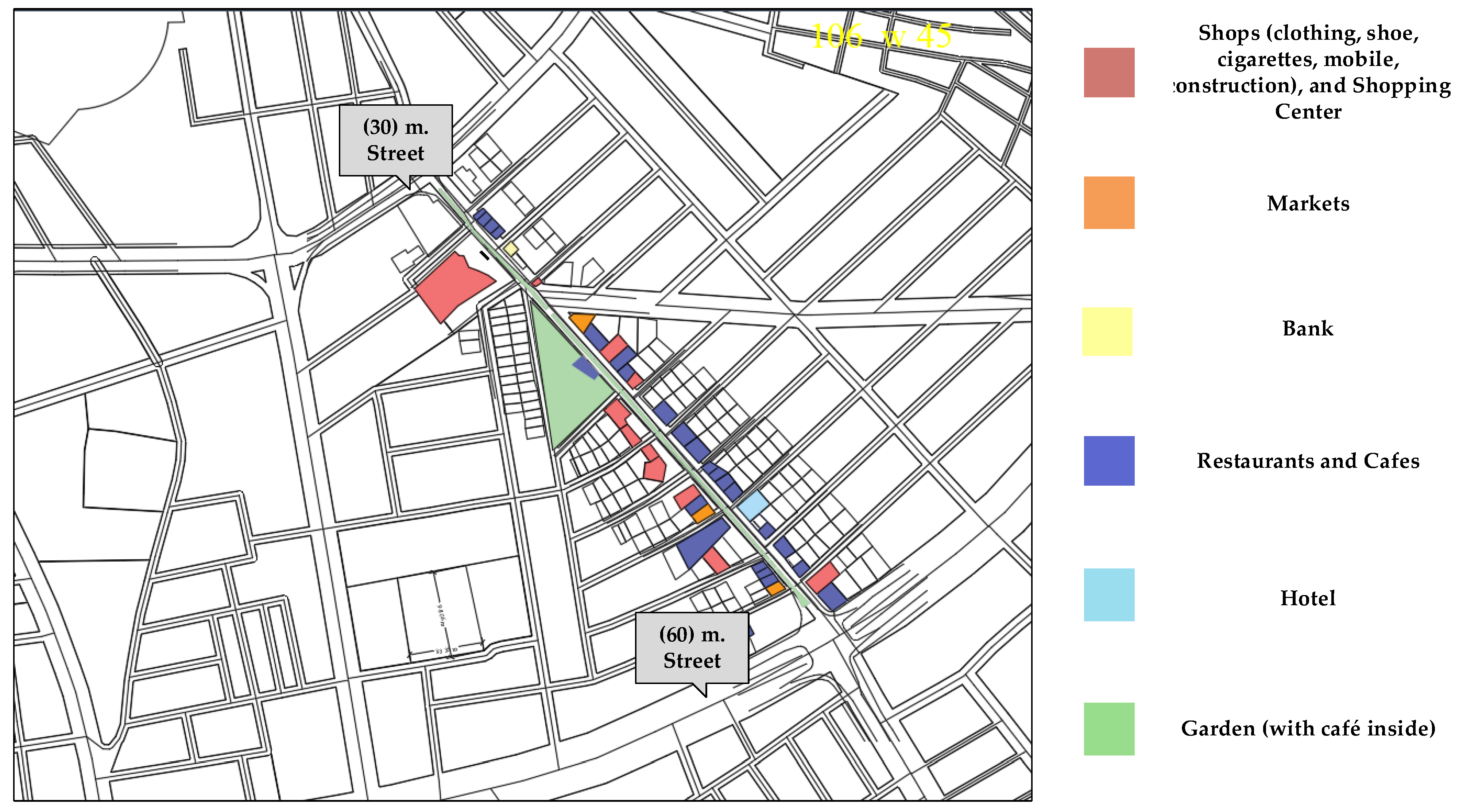

- Eskan Street is frequented by many Erbil residents, as well as tourists. The street connects two vital streets in Erbil city, the 30th Street and 60th Street, as shown in Figure 15.

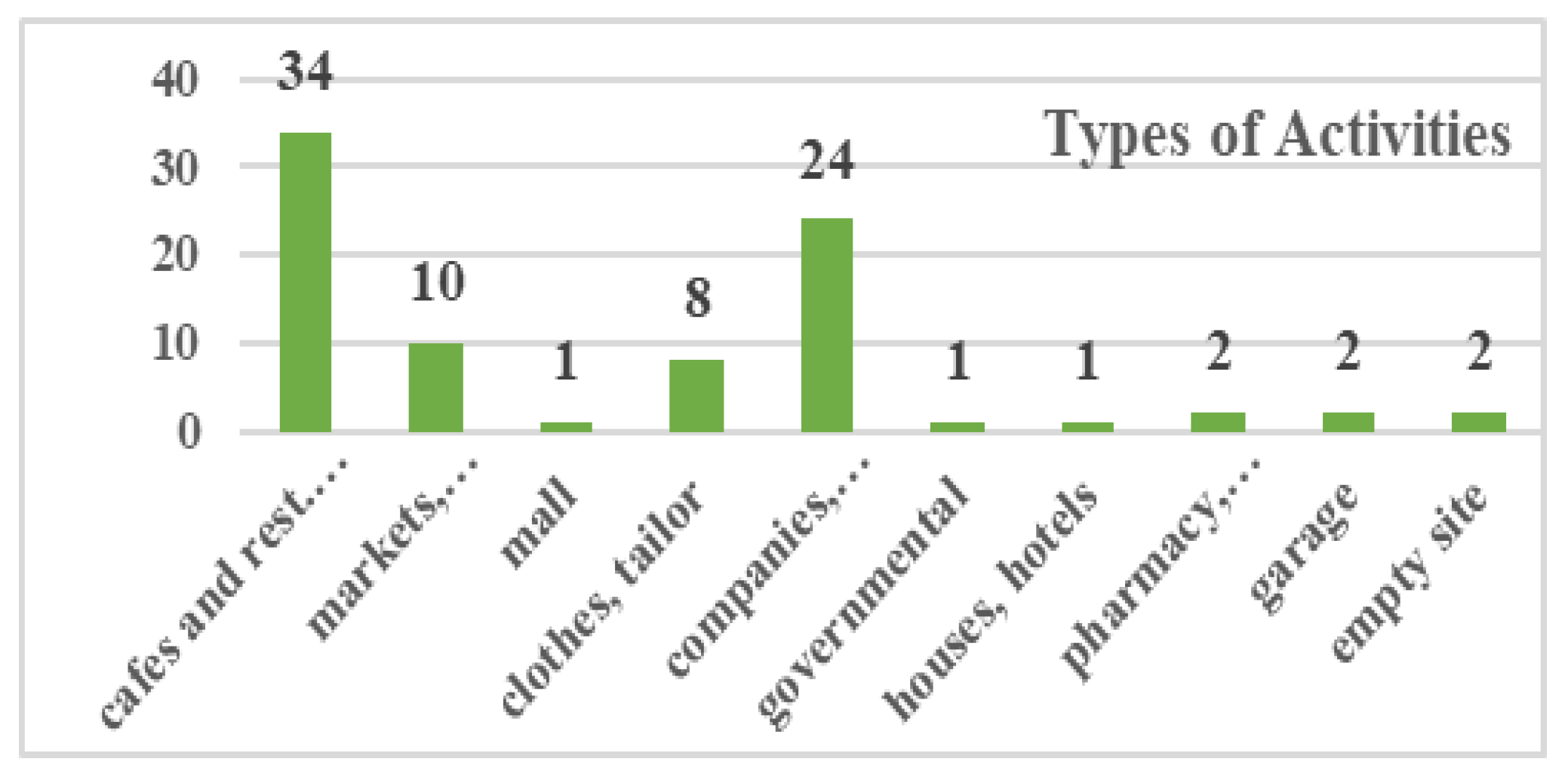

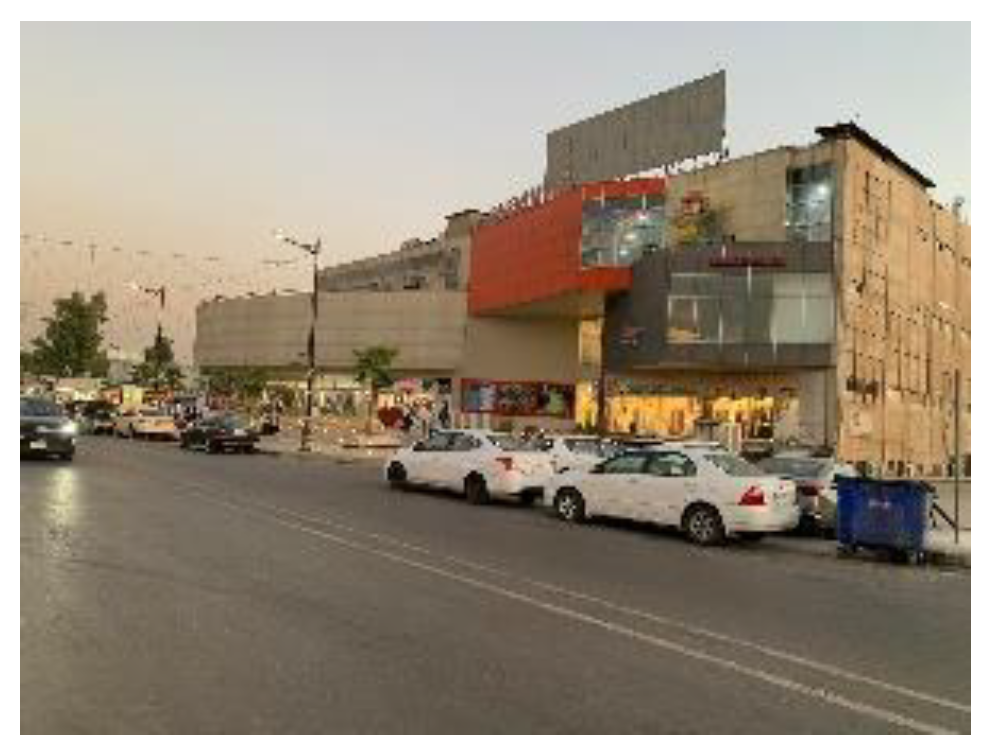

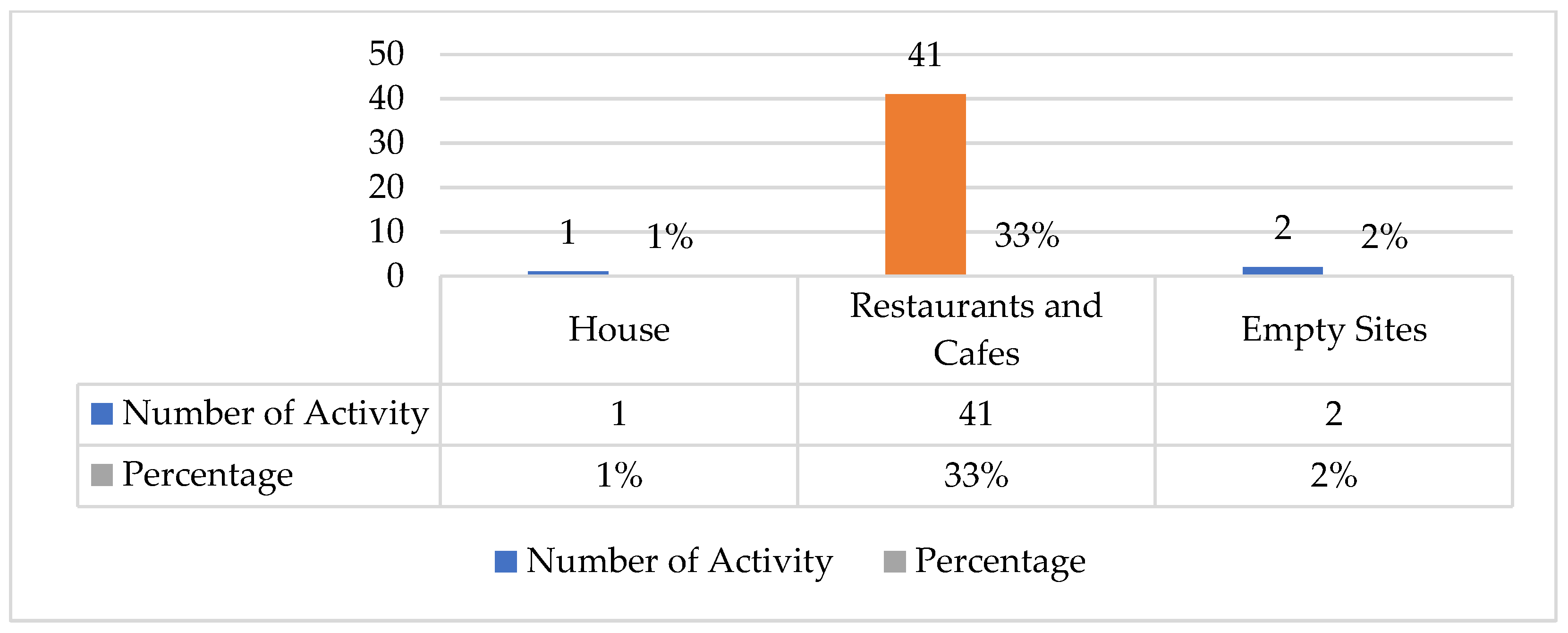

- Eskan Street is distinguished by its many activities and a variety of restaurants and cafes, most of which serve local dishes.

- It also includes other amenities, such as hotels and motels, markets, mobile shops, car shops, and clothes shops, in addition to tailoring and barber shops. At the end of the street, towards the city center via 30th Street, there is a large shopping center with many shops and various activities, as shown in Figure 16.

- The street includes several cafes, which attract many young people.

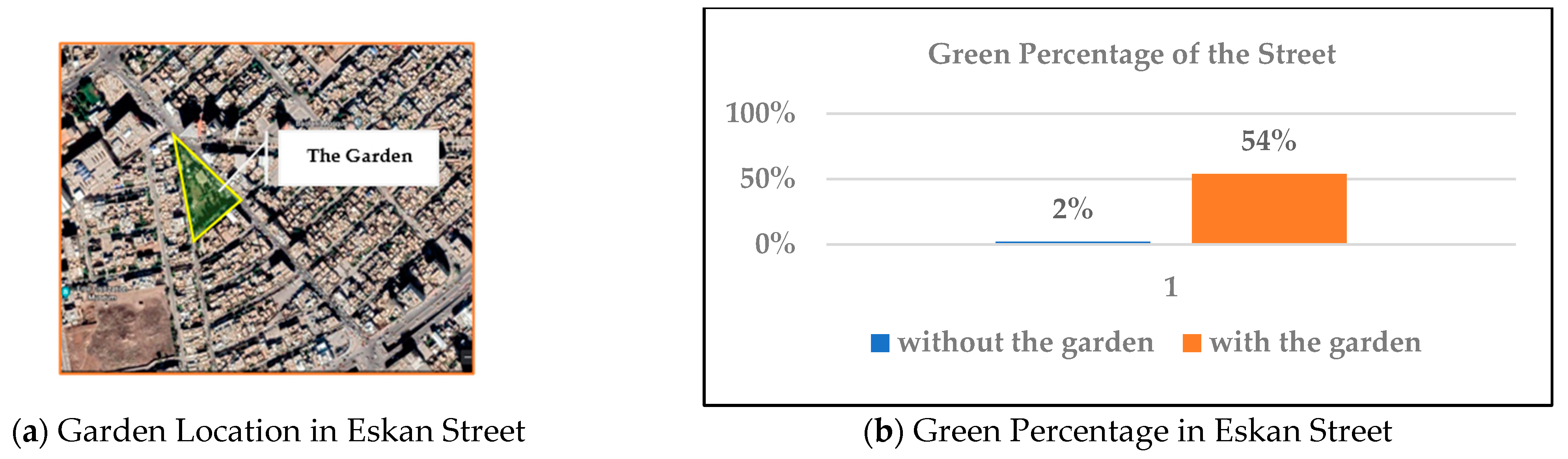

- It contains a large garden that occupies the left side of the street, with a cafeteria with an area of approximately 6592 m2.

- The length of the street is approximately 670 m, with an area of 12,226 square meters and a width of 20 m.

- The street contains many carts and booths selling local foods and juices that vary according to the seasons of the year. For further information regarded Eskan Street see the Supplementary Materials.

2.7. Methods

2.7.1. Field Survey

- We used several methods of data collection, including a field survey, which was divided into three aspects: the physical setting (urban, design, architectural details, features/seating, vegetation, diverse activities, and factors related to both streets and sidewalks), sociability, and familiarity.

- The field survey included three time periods: 9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 9:00 p.m. Information was entered into the survey table to determine the diversity, social differences, and population density, according to the time periods.

- The field survey was carried out over two seasons (summer and winter).

- In summer, the survey was performed from 15 June to 15 July, three times per day, from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., from 2:00 p.m. to 5 p.m., and from 9:00 p.m. to midnight.

- For the period of 9:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m., most of the activities occurred in supermarkets and mobile and construction shops. The busiest locations were restaurants and cafes that served breakfast to people going to work, since the street is close to the city center, where most businesses are located. After this time, the population density gradually decreased for an hour.

- Density and overcrowding increased again for the period of 12:00 p.m.–2:00 p.m. as this was typically lunchtime.

- The street vendors offered local and popular dishes and their prices were affordable, which, in addition to the close proximity to Erbil city center, were likely contributors to the increase in density.

- In the summer, for the period of 2:00 p.m.–6:00 p.m., the foot traffic decreased due to the intense heat, but the density gradually returned by 6:30 p.m.–12:00 a.m. On holidays (Friday and Saturday), the street was active until 2:00 am.

- The survey times included these specific periods to determine the population density and the most popular activities.

- Some construction shops and mobile services closed at 6:00 p.m.; however, sweet shops, markets, restaurants, and cafes were open.

- In the summer, the garden operated from 6:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m., as it was rarely used during the day due to the heat.

- The survey was repeated to identify the most important changes in activities in the winter.

- In the winter, the survey was performed from 15 December to 15 January and included three time periods: 9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 4:00 p.m.

- Juice shops switched to serving tea, coffee, and traditional sweets.

- The use of the garden changed from nighttime hours (after 6:00 pm) to daytime hours (12:00 p.m.–5:00 pm/sunset).

- In the winter, activities did not continue until midnight, instead ending around 8:00 p.m. or 9:00 p.m.

- In general, the street was more active for a longer time period in the summer, and movement usually increased in the summer after 6:00 p.m. due to the extremely hot weather during the day.

- However, after 6:00 p.m. in the winter, the movement of people decreased, and we noticed that some shop owners installed temporary nylon structures outside with a wood or gas fireplace to create a comfortable atmosphere for users.

2.7.2. Observation

- The movement of people and the population density were monitored by activity.

- The most frequently used activities, as well as the age and gender of those on the street, were recorded.

- Formal and informal activities, including eating and drinking dishes from booths and carts selling affordable local food, were observed.

- Pedestrian movement, ease of walking, accessibility, sidewalk width, suitability for movement, and the number of people using the sidewalks were recorded.

- Street crosswalks and the appropriate physical features and elements to facilitate crossings were observed.

- Amenities and seating as well as their availability within the street space and near sidewalks were recorded.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Field and Observation Results

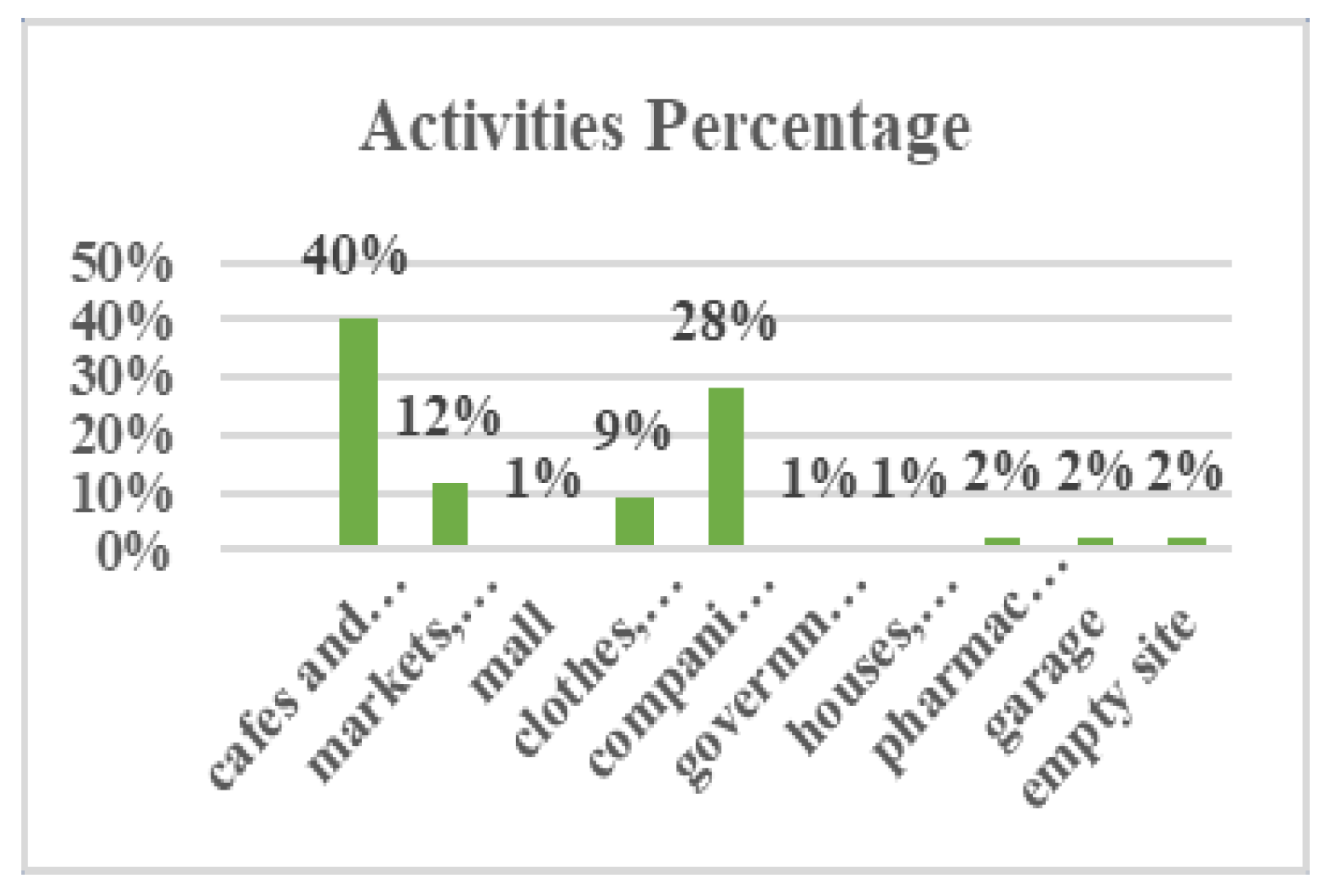

3.1.1. Activities and Land Use of Street (Sociability)

- The activities concerned mostly restaurants and cafes, and the food served varied greatly between local and fast food, attracting many people, predominantly males.

- The street had many other shops that were relevant for daily needs.

- A large shopping center on 30th Street had many shops and services that were frequented by people from all over the city, as shown in Figure 19.

- The numerous restaurants and cafes had a significant impact on attracting people, especially young people. During important events, such as the World Cup, which was held in December 2022, the street was closed to provide a suitable environment for people to move safely and to exploit the street space since the sidewalks could not otherwise handle a large number of people, as shown in Figure 20.

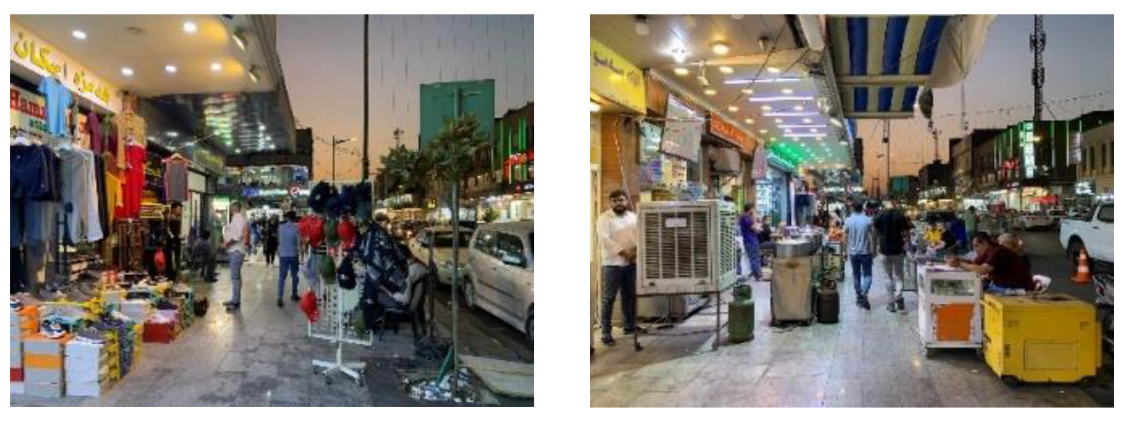

- A main attraction was the food and juice carts and booths, with a variety of meals that change based on the season, from juices and cold drinks in the summer to hot local foods and drinks in the the winter, such as tea, baklava, hummus, broad beans, and turnips. Many people bought takeaways or gathered to eat with friends as a social gathering, and the feeling of vitality was very evident, as shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22.

- The street was crowded all day, except in the early morning hours. At night, the traffic was the highest, and the speeds of motor vehicles did not exceed 30 km per hour. This provided some protection for pedestrians when crossing the street.

- The negative effects included activities that interrupted the continuity of walkability, such as shops closing early (4 p.m.) and empty sites.

- However, a positive influence was that Eskan Street was nearly devoid of houses and empty lots. This promoted the continuity of commercial facades and strengthened the spatial connection, as shown in Figure 23. Residential housing results in intermittent commercial facades, which affects the social continuity and walkability.

- Building plinths did not prohibit diverse activities and had excellent lighting at night, with a suitable pedestrian area that could accommodate up to four people, as shown in Figure 24. Plinths are a very important part of buildings, the ground floor, and the city at eye level. A building could be unpleasant, but with a lively plinth, one’s experience of it could be positive. The inverse was true, as well, as even if the building was attractive, but the ground floor was plain, the experience at the street level would not be positive [5].

- Most of the visitors to the street were males, with approximately fifty males walking or shopping on the street, as compared to approximately two women. This was one of the negative aspects of the commercial street.

3.1.2. Physical Setting

- The street sidewalks were distinguished by several positive points that encouraged walking, including a width of approximately 5 m that could accommodate up to four people, and in some parts, such as in front of the shopping center, it reached 10 m in width.

- Good tiling with unified materials and few interruptions on the same level as well as continuous sidewalks improved the walkability.

- The minimum width of the sidewalk for commercial streets in the central area was 4.8 m [53].

- The sidewalk design included three design components: the frontage zone, pedestrian zone, and fixture zone; see Figure 25.

- The height of the raised sidewalks was appropriate to prevent cars from driving on the sidewalks or cutting off pedestrian traffic.

- Despite the lack of canopies to protect pedestrians, most of the buildings were set back from the street, offering shade for pedestrians, as shown in Figure 26.

- The percentage of vegetation cover was limited, as were the number of trees, except for the afforestation on the right side of the street due to the garden that covered approximately 6592 m2 and provided a café and sitting area, as shown in Figure 27.

- There were few trees nearby, and most were not maintained. The approximate number of trees on the whole street was only 40, as shown in Figure 28. The garden was occupied by many trees, however, as shown in Figure 29. As trees protect pedestrians from the sun, ease the weather, and are aesthetic and attractive additions to a commercial street, they should be further considered here.

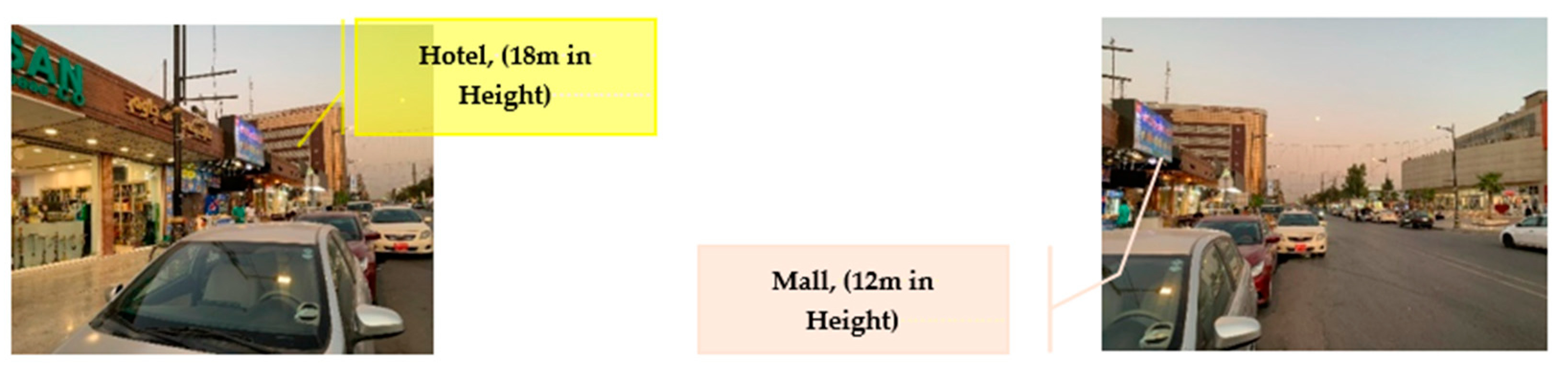

- The general lines of the building facades and within the perspective of the street were somewhat proportional and uniform in height. Most buildings were two stories tall, except for a few buildings that exceeded three stories, and one of the buildings was eight stories tall. See Figure 30.

3.1.3. Familiarity

- The street was defined by its attractions and well-known buildings, which served to distinguish Eskan Street from the streets surrounding it. Ideally, streets should be defined by buildings of different heights or functions, or even by an architectural style. Two buildings were well known on Eskan Street in general, and both were located on the 30th street, as shown in Figure 31.

- Short poles served to demarcate the sidewalk from the street and eliminate car overtaking in some areas. These columns significantly promoted pedestrian safety.

- Within the fixture zones, there were electricity poles, trees, billboards, and trash bins. These elements defined the edge, preventing cars from overtaking, and formed a clear visual axis for the street and the sidewalks on both sides, as shown in Figure 32.

- Although sidewalks were suitable for the movement of people, shop owners used them to display their goods, sell food and juices, or offer seating for their diners.

- Some buildings and restaurants took advantage of the frontage zone to add structural elements, such as raised platforms and a few steps for entry. These elements were considered an obstacle to the movement of people, and in some places, pedestrians were forced to move onto the street to continue walking, exposing them to vehicular traffic, as shown in Figure 33.

- A simultaneously positive and negative point was the availability of seating on the sidewalks, but these were the private property of restaurants and cafe owners. Therefore, only people who wanted to eat in these restaurants could use them. The street was devoid of public seating. Fixtures and their placement on the sidewalks and the street promoted the comfort and safety of pedestrians, as shown in Figure 34.

- Although the trees were limited, they provided shade and enriched the visual aesthetic on this part of the street; the contrast was obvious, as shown in Figure 35.

- One of the pedestrian attractions on the commercial street was the large shop windows. However, most shops on Eskan Street were restaurants and cafes, and many restaurants relied on using the sidewalk areas for seating. In addition, shop owners used the sidewalks to display their goods. These two issues eliminated much of the opportunity for “window shopping”.

- For shops with large, visible windows in the front, a visual connection was possible between the pedestrians and the shops. At night, this sensory connection and visual transparency was heightened due to the increased lighting, as shown in Figure 36.

- The sidewalks showed a clear visual connection via uniform tiling materials and limited obstacles within the pedestrian zone. This visual connection had an impact on many levels, including providing a unified character for the sidewalks, encouraging walking, promoting comfort while moving, and presenting a beautiful street image, as shown in Figure 37.

- Some uses of street fixtures and tree planter boxes positively attracted passersby to stop and relax or enjoy time with friends. This created an interactive atmosphere, especially since the space in front of the shopping center was spacious and could facilitate many activities, as shown in Figure 38.

- One of the points that negatively affected the aesthetic image of the street was the poor cleaning and maintenance of the street, its fixtures, and its lighting. Cleanliness is a very important factor for attracting people. In general, though, there was little interest in cleanliness, as shown in Figure 39.

- The street did not include standardized architectural styles and elements, and most designs were unique and did not follow general frameworks. One of the positive aspects of this was that some restaurant owners used traditional materials, such as bricks, to add a local character to their facades, as shown in Figure 40.

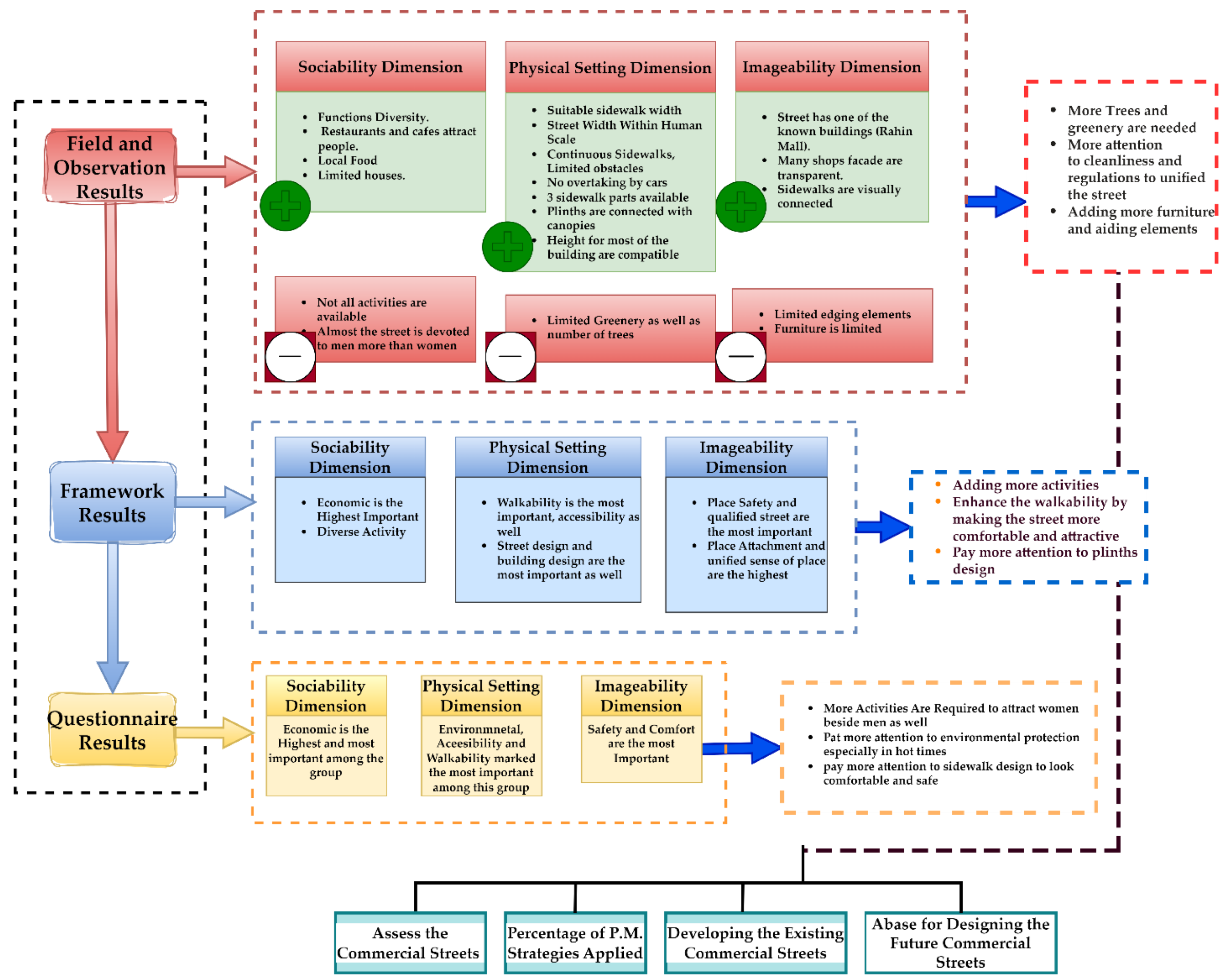

3.2. Practical Framework and Questionnaire Results

3.2.1. Practical Framework Results

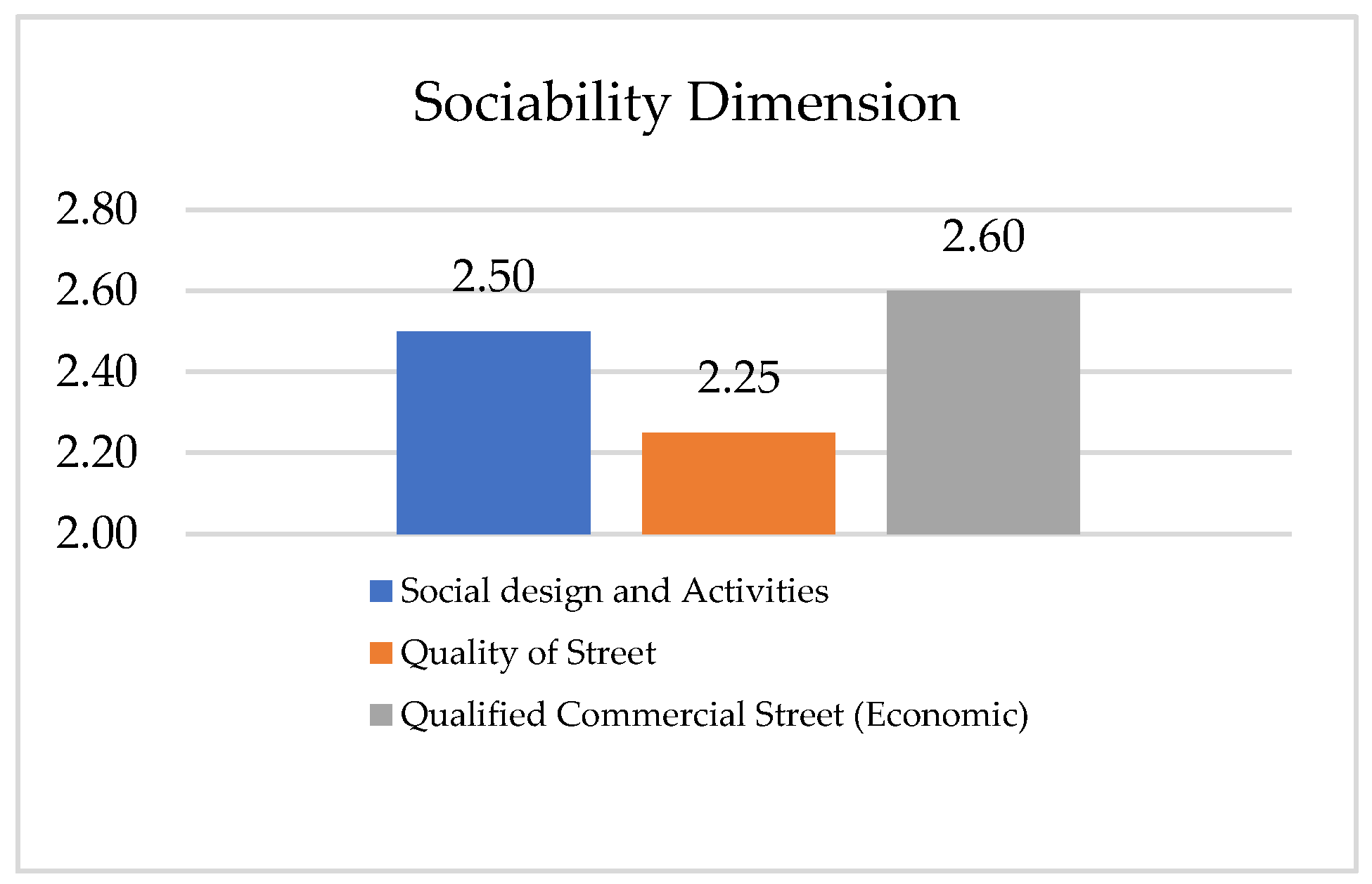

Sociability Results

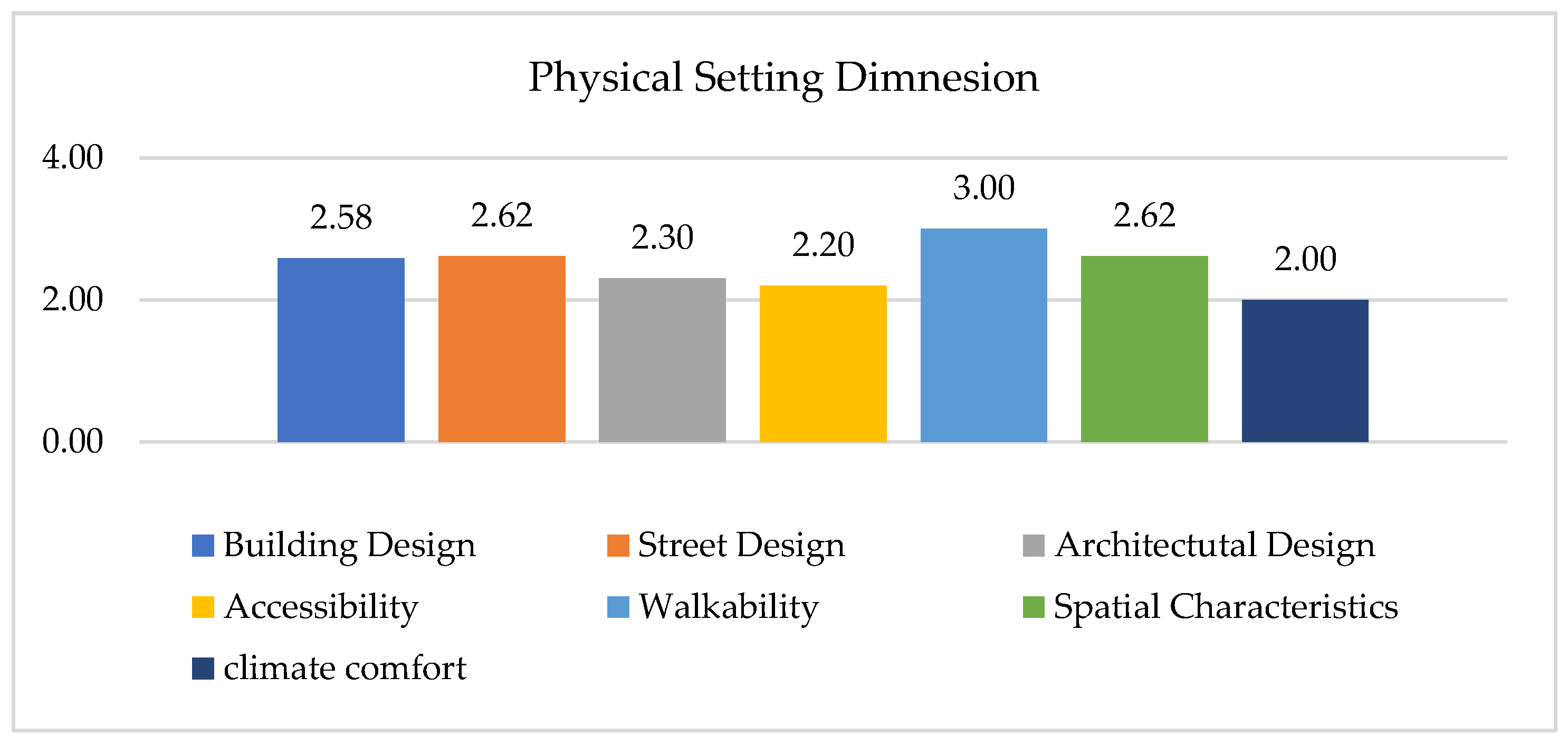

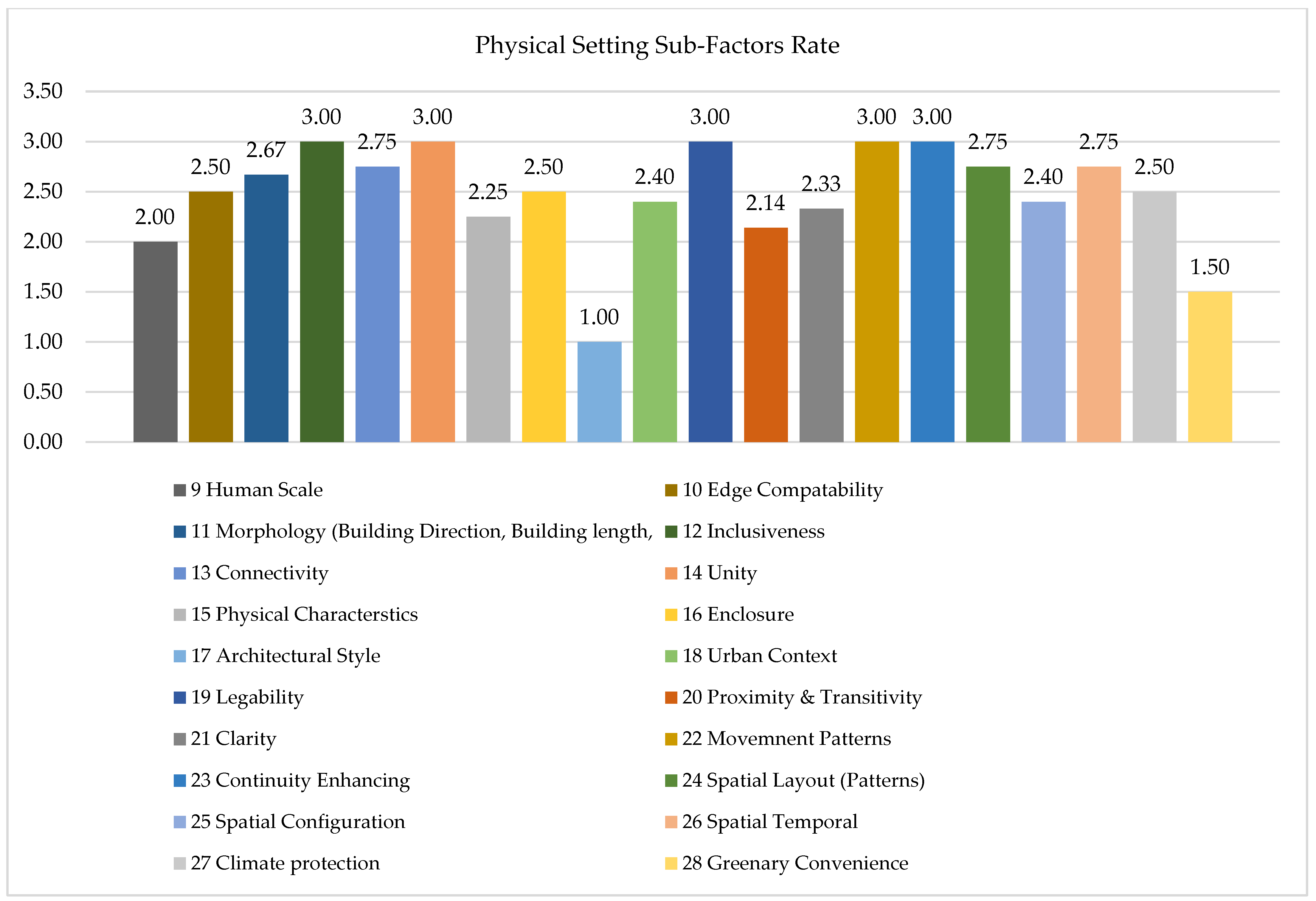

Physical Setting Results

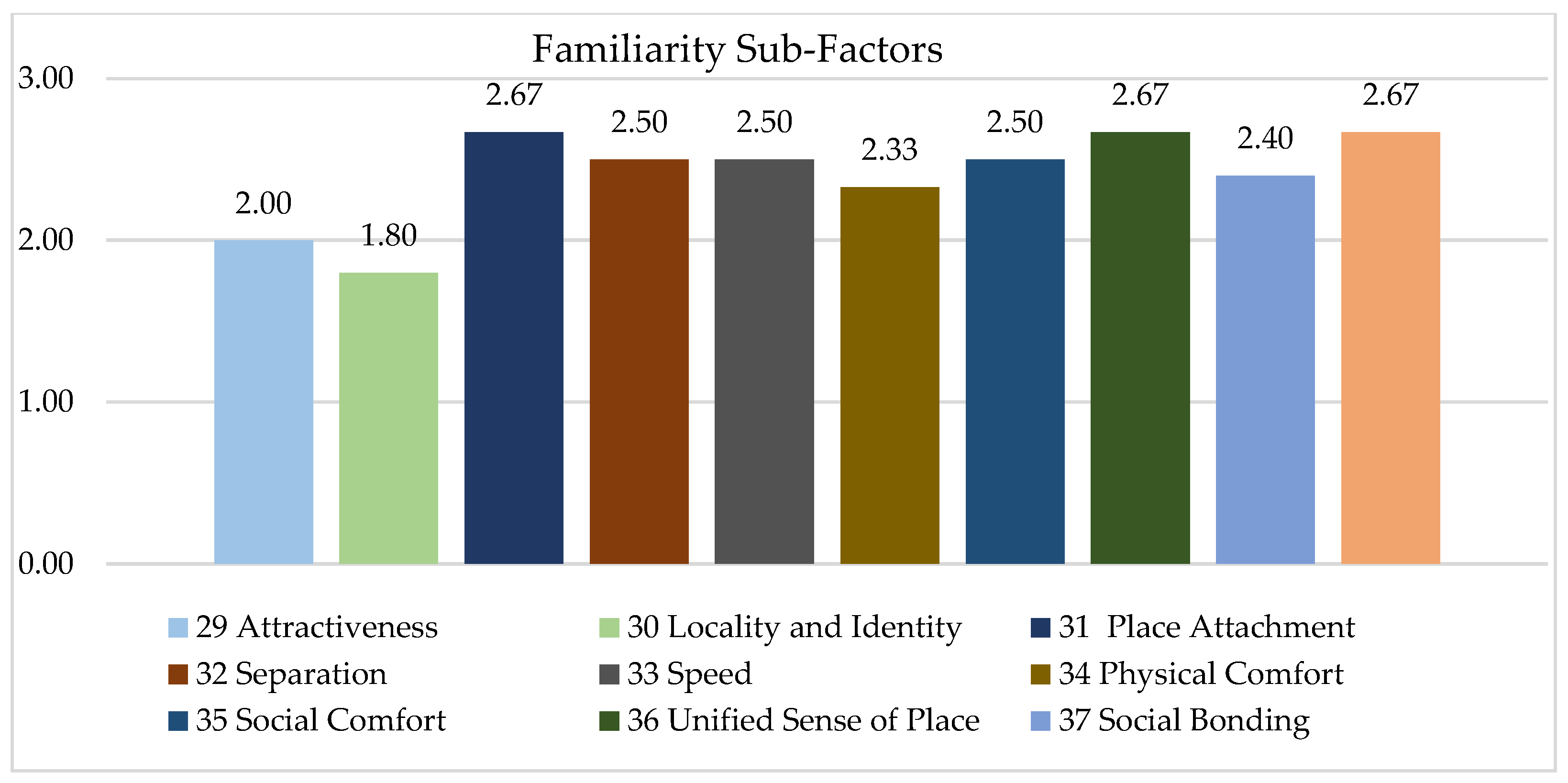

Familiarity Results

3.2.2. Questionnaire Results

- The questionnaire was directed to architects and urban designers, as the research aimed to determine systematic strategies and detailed steps for placemaking.

- A total of 100 surveys were distributed to architects. Only 62 were received, and 7 of those contained inconsistent answers (the researchers added six pairs of verification questions; if the answers were different for more than six pairs, the questionnaire was canceled).

- The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first presented a group of general questions concerning age and architectural specialization, as well as the respondent’s opinion on a comparison of seven commercial streets.

- The second part included two main aspects of the research: placemaking (which included questions regarding the three pillars of physical setting, sociability, and familiarity) and questions related to livability. Appendix C shows the questionnaire’s contents.

- The questionnaire was created similarly to the practical framework and according to the same approach, and it was built to conform to the dimensions and factors that were used in the field survey.

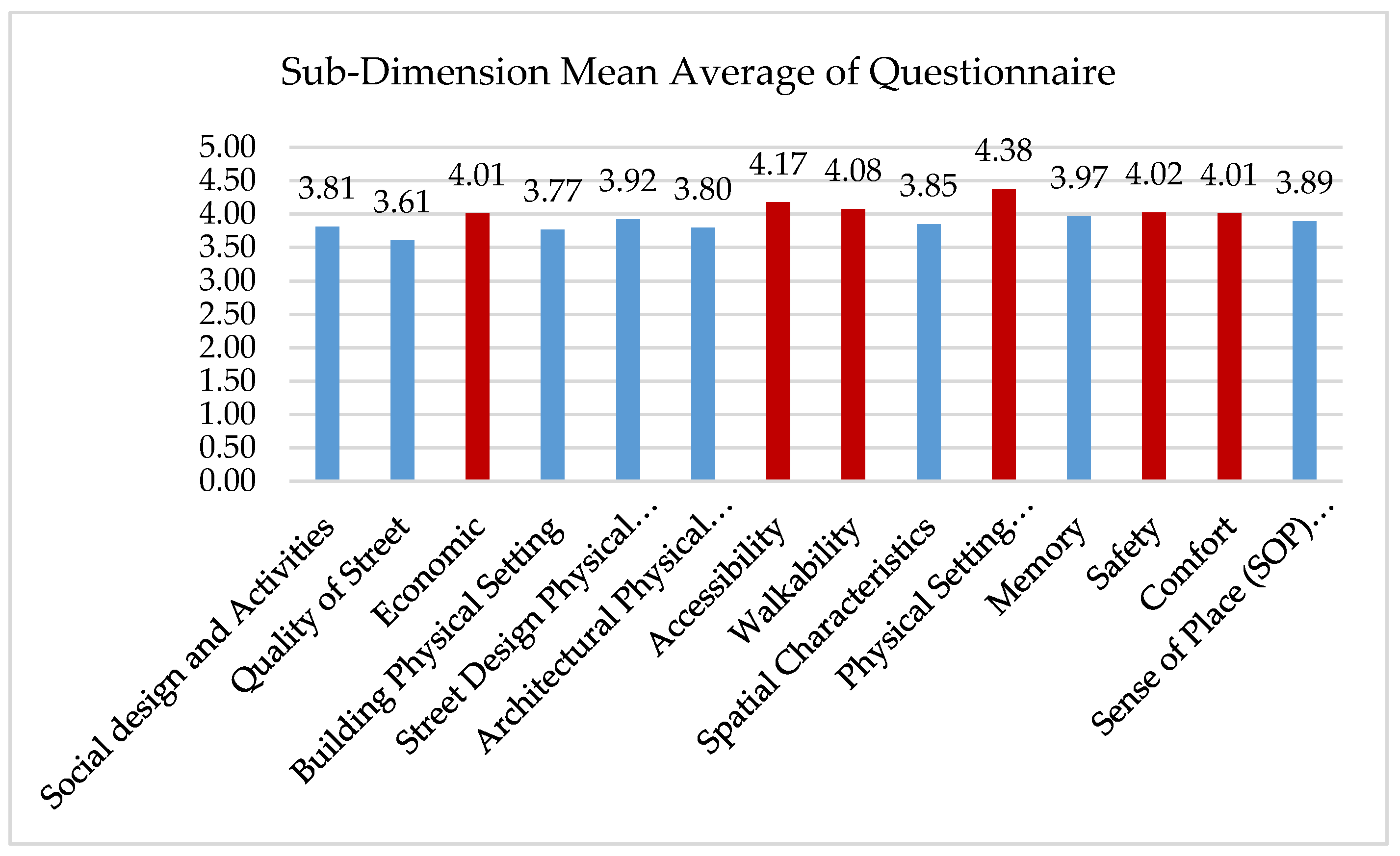

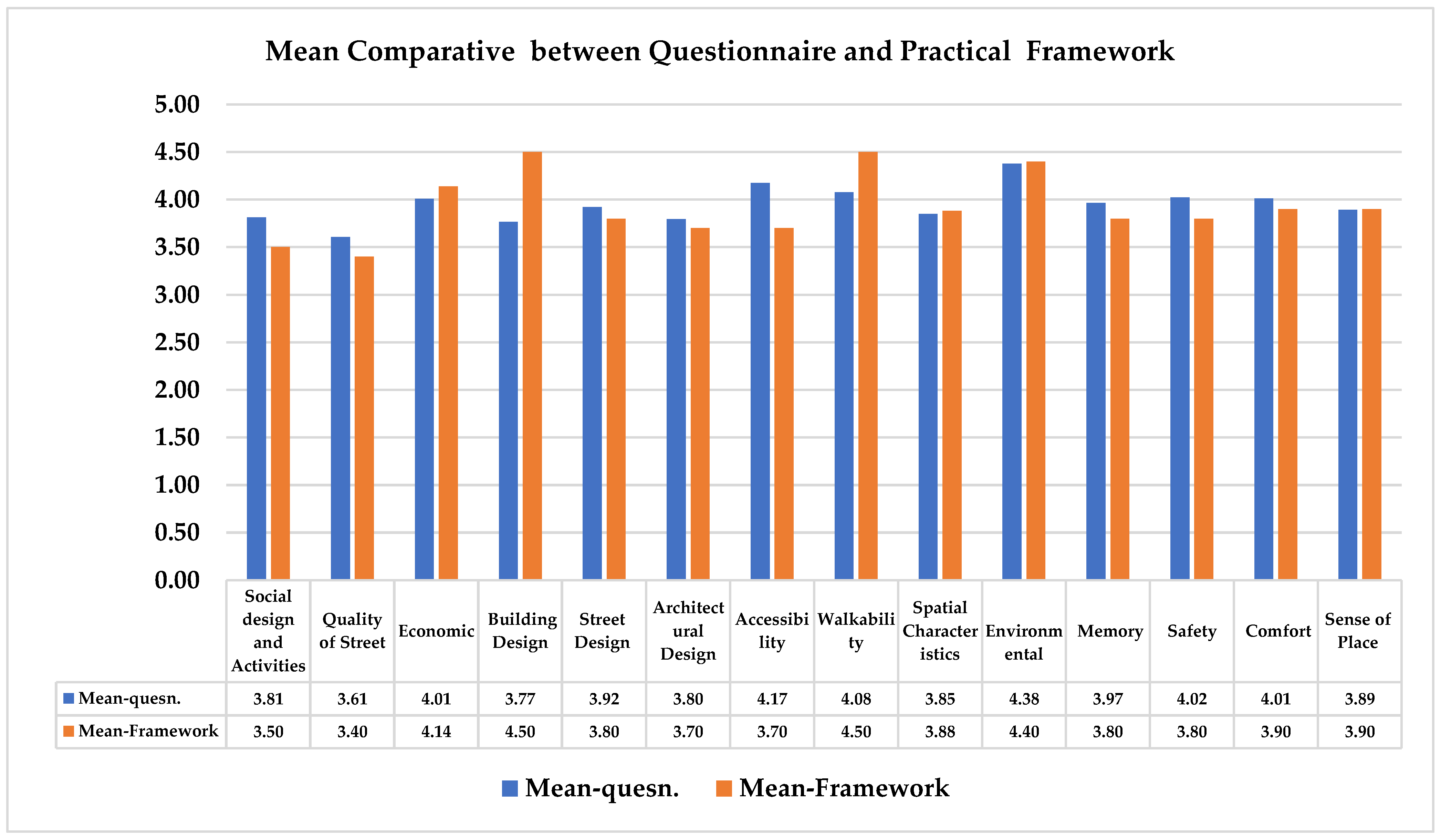

- This allowed us to easily compare the approaches. By comparing the averages of the results of the questionnaire regarding the main and secondary dimensions and factors, the most influential dimensions were comfort and safety, along with the economic factor, accessibility, and walkability. In Figure 47, the physical dimensions of the street, including sidewalk width, the availability of fixtures, activities, diversity, and beautiful Imageability, were among the most influential. These were regarded as the most important for activating livability.

- Land use diversity, the variety of restaurants, and plentiful cafes were the top reasons for choosing this commercial street, in addition to being a comfortable street, as motorist traffic is limited. It also has a shopping center with many activities, services, and various shops, as well as entertainment for children.

- Female participants expressed their desire to walk on the street, though not at all times, as Eskan Street is considered a male-dominated street due to the quality of the food in restaurants and cafes and the gathering of young people to watch soccer. However, there have not been any objections to female pedestrians using it.

- Therefore, this should be considered when developing the street’s features, as most females expressed interest in its offerings. Moreover, many females visit the shopping center, even outnumbering male shoppers, though they typically visit during different time periods.

- The first was to compare the secondary dimensions to identify the differences between the two and the importance according to different points of view.

- The second concerned the three main dimensions.

- In general, the two methods showed consistency and convergence in their results, as shown in Table 5.

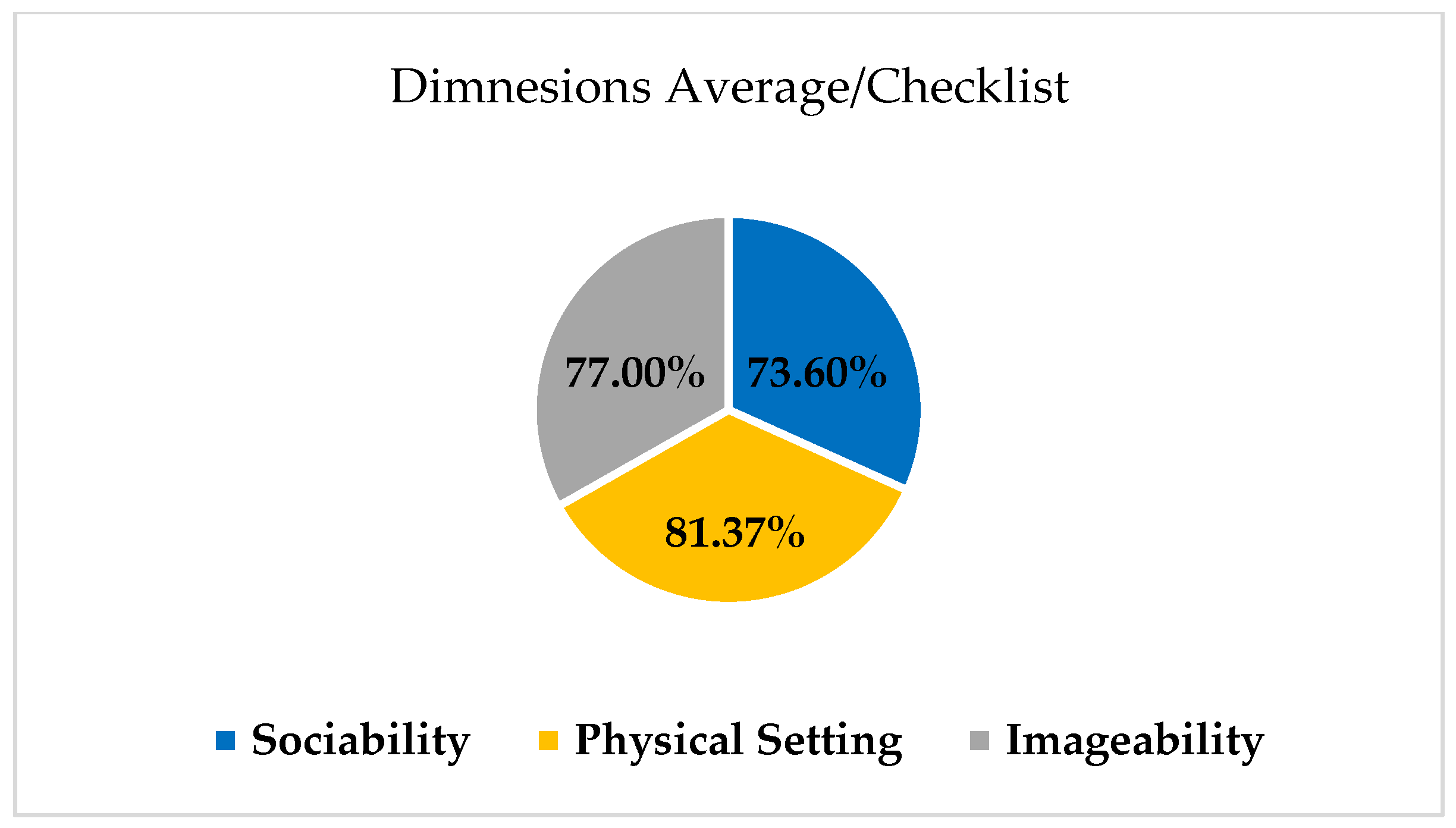

- By comparing the averages, and despite the close consistency between the results, it was clear that the physical aspects ranked the highest in both methods, with 3.99 and 4.07 for the questionnaire and the practical framework, respectively, followed by the familiarity aspect with 3.97 and 3.85, respectively.

- The last dimension in the ranking was sociability with 3.81 and 3.50, respectively.

3.3. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model No. | Models (Group 1) | Model Dimensions | Additional Dimensions | Applied Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [7] |  | Sociability | Main only | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Uses and Activities | ||||

| Access and Linkages | ||||

| Comfort and Imageability | ||||

| 2 [9] |  | Sociability | Main only | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Uses and Activities | ||||

| Access and Linkages | ||||

| Comfort | ||||

| Images | ||||

| 3 [10] |  | Sociability | Main only | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Uses and Activities | ||||

| Access and Linkages | ||||

| Comfort and Imageability | ||||

| The Shared Dimensions in this Group | The PPS Dimensions: Sociability, Uses, Activities, Access and Linkages, Comfort, and Imageability | |||

| Dimensions specified by the PPS | Additional Dimensions | |||

| Model No. | Models (Group 2) | Models Dimensions | Additional Dimensions | Applied Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 [11] |  | Sociability | Main | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Uses and Activities | ||||

| Access and Linkages | ||||

| Comfort and Imageability | ||||

| Site Interpretation | √ |  | ||

| Context and Conservation | √ |  | ||

| 5 [12] |  | Comfortable | Main | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Accessible | ||||

| Social | ||||

| Economic Growth | √ | √ | ||

| Healthy | √ |  | ||

| Community Focused | √ |  | ||

| 6 [13] |  | Sociability | Main | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Uses and Activities | ||||

| Access and Linkages | ||||

| Comfort and Imageability | ||||

| Climatic Adaption | √ |  | ||

| The Shared Dimensions in this Group | The PPS Dimensions: Sociability, Uses, and Activities, Access and Linkages, Comfort and Imageability | |||

| Dimensions specified by the PPS | Additional Dimensions | |||

| Model No. | Models (Group 3) | Models Dimensions | Additional Dimensions | Applied Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 [14] | This study presented a new, updated model explaining the importance of activating basic elements in a place, in which people and all of their five senses are linked with three other factors: social, environmental, and economic issues. Each of the five senses can be used as quantitative or qualitative indicators based on the sensation and interaction with the place. The researcher noted the importance of activating the main elements of a place [14]. | Social | Main | √ |

| Environmental | √ | √ | ||

| Economic Issues | √ | √ | ||

| Sense of Place | √ | √ | ||

| 8 [15] |  | Social | Main | √ PPS Dimensions |

| Activities | ||||

| Physical Setting | ||||

| Context | √ | √ | ||

| Meaning | √ |  | ||

| Sense of Place | √ | √ | ||

| 9 [16] |  | Social and Community | Main | √ |

| Commercial | √ | √ | ||

| Environmental and Sustainability | √ |  | ||

| Economic | √ | √ | ||

| The Shared Dimensions in this Group | The PPS Dimensions: Sociability, Environment, Economic Issues, Sense of Place | |||

| Dimensions specified by the PPS | Additional Dimensions | |||

| Model No. | Models (Group 4) | Models Dimensions | The Added Dimensions | The Used Dimensions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 [17] |  | Site | Efficiency | √ | √ |

| Distinctiveness | √ |  | |||

| Layout | √ |  | |||

| Public Realm | √ |  | |||

| Neighborhood Design | Context | √ |  | ||

| Connections | √ | √ | |||

| Inclusivity | √ | √ | |||

| Variety | √ | √ | |||

| Home | Adaptability | √ | √ | ||

| Privacy and Amenity | √ |  | |||

| Parking | √ | √ | |||

| Detailed Design | √ | √ | |||

| 11 [18] |  | Imageability | Main | √ | |

| Human Scale | √ | √ | |||

| Socio-economic and Spatial Factors | √ | √ (Individual) | |||

| Historic and Cultural Reference | √ |  | |||

| 12 [19] |  | Design | √ | √ | |

| Promotion | √ |  | |||

| Organization | √ |  | |||

| Economic Vitality | √ | √ | |||

| 13 [20] | The model is limited to a specific set of dimensions which are as follows: Open Spaces and Landscapes, Movement, and Buildings. Each dimension includes factors that work to activate the main dimension. Although the dimensions and factors are abbreviated, the model discussed an important dimension, the buildings, considering it an important element. It was one of the secondary dimensions that formed the practical framework [20]. | Open Space and Landscape | √ |  | |

| Movement | Main | √ | |||

| Buildings | √ | √ | |||

| The Shared Dimensions in this Group | The (PPS) Dimensions: Sociability, Economic and Commercial, Design, Movement | ||||

| Dimensions specified by the PPS | Added Dimensions | ||||

Appendix B

| Sociability Dimension (Sociability and Diverse Activity Dimension) (1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Sub-Factors | Possible Value | Selections | Rate | |

| Social Design and Activities (1-1) | Density | 1 | Pedestrian and vehicle flow and density | High | Excellent |

| Moderate | Fair | ||||

| Low | Very Poor | ||||

| 2 | Time functions activation | Both times are activated | Excellent | ||

| At night more than during the day | Fair | ||||

| At a specific time of day | Very Poor | ||||

| Diversity | 3 | People meeting | Available along street spaces | Excellent | |

| Available in different locations | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| 4 | Concentration of activities | Along the frontage side | Excellent | ||

| Segmented but still enhancing passing | Fair | ||||

| Segmented and does not enhance passing by | Very Poor | ||||

| 5 | Functions on street | Suitable for all ages and diverse abilities | Excellent | ||

| Suitable for men only | Fair | ||||

| Not suitable for children, and has limited diversity | Very Poor | ||||

| 6 | Availability | Along the streetscape | Excellent | ||

| Few parts of the street (gardens) | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| 7 | Restaurants and café availability | Most are cafes and restaurants | Excellent | ||

| In parts of the street (some only) | Fair | ||||

| Cafes or restaurants are very rare | Very Poor | ||||

| 8 | Different shop types | Diverse functions (huge diversity) | Excellent | ||

| Moderate Diversity | Fair | ||||

| Limited functions diversity | Very Poor | ||||

| Functionality | 9 | Street generates a sense of safety | Yes | Excellent | |

| Some | Fair | ||||

| No | Very Poor | ||||

| 10 | Street suitability for shopping | Convenient, identified as a crowded street | Excellent | ||

| Average crowding | Fair | ||||

| Inconvenient, an empty street | Very Poor | ||||

| 11 | Street functions and gathering spaces | Available with local gathering places | Excellent | ||

| Monotonous, not diverse | Fair | ||||

| Functions with no gathering places | Very Poor | ||||

| 12 | Function facilitates communication and interaction | Available on most parts of the street | Excellent | ||

| Few | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| Quality of Street (1-2) | Visibility | 1 | Commercial street accessibility within the city | Clear and accessible | Excellent |

| Clear access, but crowded | Fair | ||||

| Complicated access | Very Poor | ||||

| 2 | Formal Crossing Points | Available and clear for pedestrians | Excellent | ||

| Available but no indicator for it or it is not maintained | Fair | ||||

| No available crossing points | Very Poor | ||||

| 3 | Sidewalks relation | Connected along the street | Excellent | ||

| Separated into segments but still connected visually | Fair | ||||

| Not connected and segmented | Very Poor | ||||

| 4 | Façade transparency (in & out connection) | Excellent connection and clear | Excellent | ||

| Some parts only are connected | Fair | ||||

| Weak connection | Very Poor | ||||

| 5 | Street visibility | Visible, clear, provides a whole approach | Excellent | ||

| Visible with some obstacles | Fair | ||||

| Weak visibility | Very Poor | ||||

| Fixture Availability & Maintenance | 6 | Street fixture such as (seating and waste bins) | Available and in a good condition | Excellent | |

| Very limited or not functioning well | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| 7 | Street and sidewalk maintenance and street, as well cleanliness | Well maintained and clean | Excellent | ||

| Poorly maintained but clean | Fair | ||||

| Not maintained or clean | Very Poor | ||||

| 8 | Majority of shop lights, and street lighting | Compatible with buildings and streets, and both are available | Excellent | ||

| Only shops’ lighting is active | Fair | ||||

| No integration with street lighting or unavailable | Very Poor | ||||

| 9 | Movable shops and vendors | Attached to the shop’s elevation | Excellent | ||

| Detached and added to the façade | Fair | ||||

| Rare or not available | Very Poor | ||||

| Satisfaction | 10 | Street edges within sidewalks | Definite and clear | Excellent | |

| Some parts of the street have certain edges | Fair | ||||

| Blurred and undefined edges | Very Poor | ||||

| 11 | Green Availability | More than (50%) of the street and sidewalk area | Excellent | ||

| 25–50% from the street area | Fair | ||||

| 2–25% not available or very limited | Very Poor | ||||

| 12 | Crossing between | Clear and available | Excellent | ||

| Available but not clear with no signs | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| Qualified Commercial Street (Economic) (1-3) | Economic Satisfaction | 1 | Time Users Expand | One hour | Excellent |

| Two hours | Fair | ||||

| Less than half an hour | Very Poor | ||||

| 2 | Local Retails | Available along the street | Excellent | ||

| Some retail with local shops | Fair | ||||

| No local shops are available | Very Poor | ||||

| Adaptability | 3 | Informal shopping for more people attraction | Available in different parts of the street | Excellent | |

| Mixed with other activities | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| 4 | A mixture of formal and informal shopping | Both are available | Excellent | ||

| Only formal | Fair | ||||

| Informal only | Very Poor | ||||

| 5 | Moveable shops and vendors | Available | Excellent | ||

| In a few shops only | Fair | ||||

| Not available | Very Poor | ||||

| Physical Setting Dimension (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Dimension | Factors | Sub-Factors | Possible Value | Selections | Rate | |

| Architecture and Design (2-1) | Building Design (2-1-1) | Human Scale | 1 | Building scale | Compatible with human scale | Excellent |

| In some parts of the street only | Fair | |||||

| Not compatible with human scale | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Street proportion (width to buildings height) | 1:1 ratio | Excellent | |||

| Width > height | Fair | |||||

| Width < height | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Rows of trees | Available along the streetscape and the middle part | Excellent | |||

| In the middle part only | Fair | |||||

| Very rare or no rows of trees | Very Poor | |||||

| Edge Compatibility | 4 | Number of entrances at each segment for each 100m or each segment | 5–10 entrances | Excellent | ||

| 2–4 entrances | Fair | |||||

| <2 entrances | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Building as a façade | Forms one connected surface | Excellent | |||

| Connected with different heights | Fair | |||||

| Segmented, not connected | Very Poor | |||||

| Morphology (Building Direction, Building length, | 6 | Shops entrance direction to sidewalks | Direct connection to the sidewalk | Excellent | ||

| Through corridor | Fair | |||||

| Few steps in front mostly | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Building height | ≥2 stories | Excellent | |||

| 4–6 stories | Fair | |||||

| More than 7 stories | Very Poor | |||||

| 8 | Building’s direction with the street | Parallel with the street | Excellent | |||

| Perpendicular | Fair | |||||

| Diagonal | Very Poor | |||||

| Inclusiveness | 9 | Places are useable and accessible | Easy to access and useable | Excellent | ||

| Moderate accessibility and useability | Fair | |||||

| Difficult to access or use | Very Poor | |||||

| 10 | Activities (sitting, gathering, standing, & talking) | Varied and enjoyable | Excellent | |||

| In some parts of the street only | Fair | |||||

| Very limited or not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 11 | Safe and secure environment | Easy to walk and move | Excellent | |||

| Some cars pass on the sidewalk, not very safe | Fair | |||||

| Many cars pass on the sidewalks | Very Poor | |||||

| 12 | Temporary elements added to permanent building | Available in restaurants, cafes, and other shops (mostly) | Excellent | |||

| In some clothing shops and markets | Fair | |||||

| No added elements or very limited | Very Poor | |||||

| Architecture and Design (2-1) | Street Design (2-1-2) | Connectivity | 1 | Street connection with building | Directly connected (no barriers) with wide spaces | Excellent |

| Barriers available (trees and fixture) | Fair | |||||

| Weak connection, or very limited space | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | building connections with sidewalks | Connected through the frontage zone | Excellent | |||

| Connected through the pedestrian zone | Fair | |||||

| Connected through the fixture zone | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Parts of the street | Seen with no obstacles or limited | Excellent | |||

| Various obstacles block the view | Fair | |||||

| Obstacles and building shape harms pedestrian | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Buildings linked together | Continuously connected | Excellent | |||

| Partial bonding | Fair | |||||

| Separated or segmented | Very Poor | |||||

| Uniformity | 5 | Height uniformity | Same building height (almost) | Excellent | ||

| Different heights | Fair | |||||

| Some buildings extend the limited diversity | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Materials and Colors | Same for all buildings | Excellent | |||

| Groups have the same materials | Fair | |||||

| Different materials and colors | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Building Elements | Aligned to the main axis | Excellent | |||

| Different alignment axis | Fair | |||||

| No definite alignment | Very Poor | |||||

| Physical Characteristics | 8 | The presence of special needs equipment in the street | Available within the street design | Excellent | ||

| Available but not standardized | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 9 | Number of street lanes | Only one | Excellent | |||

| Two lanes | Fair | |||||

| More than two | Very Poor | |||||

| 10 | Sidewalks width compatible for walking | ≥5 m, or accommodate 4 or more people | Excellent | |||

| 2–4 m, or accommodates 2–4 people | Fair | |||||

| <2 m, or less than 2 people | Very Poor | |||||

| 11 | Sidewalks contain three design parts: fixture zone, pedestrian zone, and frontage zone | Contains all the three main zones | Excellent | |||

| Contains both fixture and pedestrian zone or the frontage zone with pedestrian only | Fair | |||||

| Sidewalk in some parts of the street disappears | Very Poor | |||||

| Enclosure | 12 | Height & width relation (between street width and building height) | Vertical elements are proportionately related to the width (some compatible) | Excellent | ||

| The height of some buildings is not compatible with most heights | Fair | |||||

| Width more than height | Very Poor | |||||

| 13 | Building Elevation | Connected and continues | Excellent | |||

| Segmented into short groups | Fair | |||||

| Segmented with dead spaces | Very Poor | |||||

| Architecture and Design (2-1) | Architectural Design (2-1-3) | Architectural Style | 1 | Buildings’ architectural features | Most with architectural features | Excellent |

| Some only | Fair | |||||

| No architectural features | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Shops arch. theme | Function and arch. theme matches | Excellent | |||

| Function and arch. theme appears in some shops | Fair | |||||

| No matching theme | Very Poor | |||||

| Urban Context | 3 | Building integration with the urban context | Connects to physical surroundings | Excellent | ||

| Some parts only | Fair | |||||

| Contrasting | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Street patterns | Accommodates both | Excellent | |||

| Accommodates pedestrian movement more | Fair | |||||

| Accommodates cars’ movement more than pedestrian movement | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Building form | Reflects the function | Excellent | |||

| Reflects different function | Fair | |||||

| No reflection | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Network of routes and spaces | Clear;y connected, no dead spaces | Excellent | |||

| Fragmented without dead spaces | Fair | |||||

| Segmented with dead spaces | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Building response to site | Positively responds to orientation and walking pedestrians (the emergence and receding of building blocks) with shading | Excellent | |||

| Moderate response | Fair | |||||

| Weak response to the site | Very Poor | |||||

| Simplicity | 8 | Design inclusiveness of street buildings | Active, safe, and accommodates different cultural backgrounds, affordable | Excellent | ||

| Moderate | Fair | |||||

| Very low | Very Poor | |||||

| 9 | Building height | Almost same height | Excellent | |||

| Few differences | Fair | |||||

| Significant differences in height | Very Poor | |||||

| 10 | Clear approach | Buildings appear as one continuous building | Excellent | |||

| Buildings are fragmented, but still connected visually | Fair | |||||

| Fragmented, with no connection | Very Poor | |||||

| Access and Linkages (2-2) | Accessibility (2-2-1) | Proximity to transit | 1 | Car movement and parking accessibility | Accessible and connected | Excellent |

| Accessible but far | Fair | |||||

| Not accessible (no available parking) | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Affordability of transport options | Private cars and public transportation | Excellent | |||

| Private cars with limited public transportation | Fair | |||||

| Private cars only | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Moving from parking lots to sidewalk place | Easy directly on street edges and parking lots | Excellent | |||

| On parking lots only, clear and close | Fair | |||||

| Faraway or not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | The transition between the two sides | Available, clear, and well designed | Excellent | |||

| Available but not clear | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Transition between sidewalks segments | Walking is easy and connected | Excellent | |||

| Connected with some obstacles | Fair | |||||

| Very bad connection and not easy to cross | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Cyclists and people with mobility handicaps spaces | Available, well maintained | Excellent | |||

| Available, but not functioning well | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Movement separation between vehicles and pedestrians | Separated by different levels and rows of trees and different pavement materials | Excellent | |||

| Different levels only | Fair | |||||

| Weak separation | Very Poor | |||||

| Clarity | 8 | Access to shops, accessible to eat and sit spaces | Readable and connected, corresponding to people’s needs | Excellent | ||

| Accessible with some obstacles | Fair | |||||

| Not clear nor visible (limited) | Very Poor | |||||

| 9 | Movement between shops | Easy to read by pedestrians | Excellent | |||

| Obstacles in prevent movement | Fair | |||||

| Not easy to recognize | Very Poor | |||||

| 10 | Identified access to formal shopping | Obvious | Excellent | |||

| Obvious with some obstacles | Fair | |||||

| Very weak access | Very Poor | |||||

| Movement Patterns | 1 | Street activities | Diverse activities attract people to walk | Excellent | ||

| Diverse activities, but sidewalk does not encourage walking | Fair | |||||

| No diverse activites and not easy to walk | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Pedestrian movement | Constant movement along the street | Excellent | |||

| Intermittent, only in some places | Fair | |||||

| Low pedestrian movement | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | The link between urban form and commercial streets sidewalks | Easily accessible | Excellent | |||

| Accessed with some barriers | Fair | |||||

| Complicated, not easy to access | Very Poor | |||||

| Continuity Enhancing | 4 | Plinth edges enhance walking and staying | Continuous edge conforms to human scale | Excellent | ||

| Connected, with some barriers | Fair | |||||

| Segmented, not compatible with human scale or activated functions | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Obstacles in sidewalks | Free from obstacles, continuous view | Excellent | |||

| In some parts only | Fair | |||||

| Generators, old structures, or street lighting features distributed along the pedestrian zone | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Aesthetically pleasing street | Functional and architectural diversity create an aesthetic approach | Excellent | |||

| Diversity of architectural features and elements only | Fair | |||||

| It is not aesthetically pleasing | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Frontage zone | Well designed, connected with mixed activities | Excellent | |||

| Some parts are designed | Fair | |||||

| Weak design and connection | Very Poor | |||||

| Access and Linkages (2-2) | Spatial Characteristics (2-2-3) | Spatial Layout (Patterns) | 1 | Parking types and their proximity to the commercial street | Different parking types (on edges and close parking lots) | Excellent |

| On edges only and designed within the street | Fair | |||||

| On edges | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Delineate street | Pavement materials, guideposts, and raised pavement markers | Excellent | |||

| Pavement materials differ | Fair | |||||

| Only raised pavement markers | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Integration inside and outside shops | Open to the outside and connected | Excellent | |||

| Not completely separated nor connected | Fair | |||||

| No connection | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Sidewalk hierarchy | A clear transition between the street, walkway, and building | Excellent | |||

| No fixture zone separating the street space and building or weak fixture zone | Fair | |||||

| Both the pedestrian zone and fixture zone have a weak appearance | Very Poor | |||||

| Spatial Configuration | 5 | Location of the resting places in space | Available in the fixture zone | Excellent | ||

| Available in the pedestrian zone | Fair | |||||

| Not available or very limited | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Built environment and human behavior | Meets pedestrians’ movement needs | Excellent | |||

| Suitable in terms of the variety of activities, but not suitable for movement | Fair | |||||

| Does not include a variety of activities and is not suitable for walking | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | The demarcation between public and private zones | Clear and visible with the availability of street fixtures | Excellent | |||

| Demarcation available but both are at the same level | Fair | |||||

| Not clear nor visible | Very Poor | |||||

| 8 | Landscape area to street area | 25–30% | Excellent | |||

| 15–5% | Fair | |||||

| 5% or very limited | Very Poor | |||||

| 9 | Landscape type | Mix of trees, grass, and flowerpots | Excellent | |||

| Only trees | Fair | |||||

| No greenery | Very Poor | |||||

| Availability | 10 | Time pedestrians spend on street | ≤3 Hours | Excellent | ||

| 1–2 Hours | Fair | |||||

| >1 Hour | Very Poor | |||||

| 11 | Schematic approaches to reduce speed | Width of the sidewalks, with different levels and pavement. | Excellent | |||

| Different levels and pavements. | Fair | |||||

| No approaches to reduce speed | Very Poor | |||||

| 12 | Extending activities at nighttime | Extended to 12:00 AM | Excellent | |||

| <12:00 AM | Fair | |||||

| Max till 10:00 PM | Very Poor | |||||

| 13 | Function diversity | More people due to function diversity, more time | Excellent | |||

| More people but not diverse functions, less time | Fair | |||||

| Fewer people, less diversity, and less time expended | Very Poor | |||||

| Environmental Dimension (2-3) | Climate Comfort | Climate protection | 1 | Shading on sidewalks & availability of canopies | Available as a part of building and street design | Excellent |

| Very limited attachment to building façade | Fair | |||||

| No shading devices | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Sunlight in the street (according to sun direction) | Sunny on both sides | Excellent | |||

| One side is sunny | Fair | |||||

| Both sides are not in the sun | Very Poor | |||||

| Greenery | 3 | Green Spaces | Part of street design | Excellent | ||

| Parks on sides of street | Fair | |||||

| No green spaces | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Sidewalks and street vegetation | Available in the middle part of sidewalks | Excellent | |||

| In the middle only | Fair | |||||

| Very limited greenery | Very Poor | |||||

| Familiarity Dimension (3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Dimension | Factors | Sub-Factors | Possible Value | Selections | Rate | |

| Images (3-1) | Place Memory | Attractiveness | 1 | Green availability on streets and sidewalks | Available and well maintained | Excellent |

| In the middle parts mostly | Fair | |||||

| Not available or very limited | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Street image | Creates a positive image, comfortable, and attractive | Excellent | |||

| Neutral effect | Fair | |||||

| Creates a negative image, not comfortable | Very Poor | |||||

| Locality and Identity | 3 | Traditional and local features | Available | Excellent | ||

| Contemporary features with traditional | Fair | |||||

| No traditional features | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Historical elements | Available and clear | Excellent | |||

| Mixed with contemporary elements | Fair | |||||

| No historical elements | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Local activities | Available and diverse | Excellent | |||

| A few | Fair | |||||

| No local activities | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Building styles and approaches | Generates meaning | Excellent | |||

| In some limited buildings | Fair | |||||

| No meaning or sense perception | Very Poor | |||||

| 7 | Known street | Has a distinctive architectural character | Excellent | |||

| Has various services and activities that people need | Fair | |||||

| Has distinctive landmarks or locality | Very Poor | |||||

| Place Attachment | 8 | Place and person relation | Friendly and familiar | Excellent | ||

| Moderate familiarity | Fair | |||||

| Weak connection | Very Poor | |||||

| 9 | People in streetscape | Walking and sitting around | Excellent | |||

| Walking only, no sitting available | Fair | |||||

| Not able to sit or walk | Very Poor | |||||

| 10 | Street environment | Reflects people’s needs | Excellent | |||

| Reflects some needs only | Fair | |||||

| Does not reflect all people’s needs | Very Poor | |||||

| Images (3-1) | Place Safety | Separation | 1 | Curbs (edging stone or pavement raised path), bollards, guard railing | Available | Excellent |

| Available but difficult to realize | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Streets and sidewalks isolated throughout | Using levels, pavement materials, trees, and fixtures | Excellent | |||

| Levels only | Fair | |||||

| Weak isolation | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Parking spaces | Available/directly attached to sidewalks | Excellent | |||

| Available, parking lots <1 km away, and attached parking | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Crossing points | Available at a specific distance as well as clear and designated | Excellent | |||

| Available but not maintained nor designated | Fair | |||||

| Available but barely visible | Very Poor | |||||

| Speed | 5 | Car speed | 35–50 km/h | Excellent | ||

| 50–70 km/h | Fair | |||||

| <70 km/h | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Car movement | Is restricted | Excellent | |||

| In some parts of the street | Fair | |||||

| Not controlled | Very Poor | |||||

| Place Comfort (3-3) | Physical Comfort | 1 | Pedestrian fencing, trees as physical separation | Rows of trees and fencing lines or other fixtures (benches or trash bin) | Excellent | |

| Trees only | Fair | |||||

| Not available, or limited | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Pedestrian traffic light in street | Available at the end edges of the street | Excellent | |||

| Available at the center of the street | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Sidewalk pavement | Accommodates walking and different activities | Excellent | |||

| Accommodates walking, not maintained | Fair | |||||

| Does not encourage walking | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Parking integration | Integrated, as a part of street design | Excellent | |||

| Integrated, on the sides only | Fair | |||||

| Parking is not designed | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Frontage area | Well designed with a specific area | Excellent | |||

| Not clear in some parts, moderate design | Fair | |||||

| Very poorly designed | Very Poor | |||||

| 6 | Sidewalk and seating areas | Part of sidewalk fixture as well as cafes and restaurants | Excellent | |||

| Part of cafes and restaurants only | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| Social Comfort | 7 | Sense of familiarity | With people and functions | Excellent | ||

| Moderate familiarity | Fair | |||||

| Not familiar | Very Poor | |||||

| 8 | Land use and function variety, density | Mixed activities for all people, with a high density | Excellent | |||

| Limited activities, for all people, but with a high density | Fair | |||||

| Few activities with a low density | Very Poor | |||||

| Sense of Place (3-2) | Linked to Street, Identity, Qualified Street | Unified Sense of Place | 1 | Cultural events available in street space or on sidewalks | Always available | Excellent |

| Some buildings or functions in street held a cultural event | Fair | |||||

| No events are available | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Street atmosphere | Attractive, accessible, and walkable | Excellent | |||

| Accessible, and walkable but not attractive | Fair | |||||

| Not attractive and not easy to move through | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Clear direction in street | Distinct landmarks, with diverse activities | Excellent | |||

| Landmarks available, with limited activities | Fair | |||||

| No clear landmarks | Very Poor | |||||

| Social Bonding | 1 | Local activities and amenities availability | Local activities available and values | Excellent | ||

| Mixed values, local and contemporary | Fair | |||||

| No specific local value | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | Possibility of sitting and eating | Available (public and private) | Excellent | |||

| Available but as a part of restaurants and cafes | Fair | |||||

| Not available | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | Street design accommodation for movement | Accommodate moderate movement | Excellent | |||

| Compatible with moderate movement, but a weak connection between the two sides | Fair | |||||

| Compatible with fast movement and weak connection with the sides | Very Poor | |||||

| 4 | Safe mobility between sidewalks and street | Definite edges, different levels, and differences in pavement materials | Excellent | |||

| Parking on edges or easy-to-reach and clear | Fair | |||||

| Weak mobility | Very Poor | |||||

| 5 | Architectural language and style | It includes a distinctive and unified language on most of the street buildings | Excellent | |||

| Some street buildings have a distinctive language | Fair | |||||

| It does not include any distinct language | Very Poor | |||||

| Sense of Belonging | 1 | Building–street connection | Supports the street as a place | Excellent | ||

| The relation is monotonous | Fair | |||||

| Creates negative spaces, not connected to people | Very Poor | |||||

| 2 | People connection with place | Activities meet all people’s needs | Excellent | |||

| Some activities (some meet people’s needs) | Fair | |||||

| Street activities do not meet anyone’s needs | Very Poor | |||||

| 3 | People’s commitment towards the street | Yes | Excellent | |||

| A few people | Fair | |||||

| No | Very Poor | |||||

Appendix C

| Questionnaire Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Salahaddin University College of Engineering Architectural Department Research Title Placemaking Strategies Enhancing the Livability of Commercial Streets in Erbil City | |

| Dear Sir/Madam | |

| This is a pure academic thesis work to cover part of the requirements for obtaining a Ph.D. in Architectural Engineering at Salahalddin University, College of Engineering, Architectural Department. The study aims to assess Livability in commercial streets by activating placemaking steps, as well as how it will affect pedestrian’s life in the street. This questionnaire includes a set of questions that will be answered by Architects, Architectural Academics (Master’s and Ph.D. holders), to identify the best design strategies for commercial streets regarding enhancing livability. Please read each question and each choice carefully and give an appropriate answer according to your experience and understanding of the topic. Bear in mind that, this information is purely academic. Your cooperation and participation are very important in supporting the research and its results. Thank you for your valuable help. | |

| Ph.D. Student; Ansam Saleh Al Hadidi | |

| Dr. Saalahaddin Yasin | |

| Email: [email protected] | |

| Mobile: 07706518931 | |

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| A1. Academic achievement | A1.1. Bachelor | A1.2. M.Sc. Degree | A1.3. Ph.D. Degree | |||||

| A2. If you are specialized in Architecture, please specify your specialty | ||||||||

| A3 Age | A3.1 24–39 | A3.2 40–60 | A3.3 60 and above | |||||

| ||||||||

|  | |||||||

| ||||||||

| B1. Which Street/Streets from the following commercial streets you are familiar with? You can choose more than, one if you want. | ||||||||

| Baxtiary | Eskan | Brayaty | Shorsh | MallaAfandy | Adalla | Runaky | ||

| B.1.1 | B.1.2 | B.1.3 | B.1.4 | B.1.5 | B.1.6 | B.1.7 | ||

| B2. Select the reason/s behind your selection. | ||||||||

| B2.1 | Is it accessible? | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.2 | Good cafes and restaurants? | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.3 | Clothing shops (brands)? | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.4 | Availability of local shops? | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.5 | Mixed activities for all people | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.6 | The street has a beautiful environment | Yes | No | |||||

| B2.7 | Others? Please identify | |||||||

|  | |||||||

| B3. Which Streets/Streets from the following are more livable from your point of view? You can choose more than one if you want. | ||||||||

| Baxtiary | Eskan | Brayaty | Shorsh | MallaAfandy | Adalla | Runaky | ||

| B3.1 | B3.2 | B3.3 | B3.4 | B3.5 | B3.6 | B3.7 | ||

| B4. Select the reason/s behind your selection. | ||||||||

| B4.1 | Is it accessible? | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.2 | Good cafes and restaurants? | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.3 | Clothing shops (brands)? | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.4 | Availability of local shops? | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.5 | Mixed activities for all people | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.6 | The street has a beautiful environment | Yes | No | |||||

| B4.7 | Others? Please identify. | |||||||

|  | |||||||

| B5. Transparent shop fronts (show the insides of the shop), effects on: | ||||||||

| B5.1 | Spending more time on shop façade | |||||||

| B5.2 | Attracting people to walk | |||||||

| B5.3 | Doesn’t attract me at all | |||||||

| B6. When the number of building entrances increases: | ||||||||

| B6.1 | It will attract people as they have more options to look, stay, and walk | |||||||

| B6.2 | Doesn’t affect them | |||||||

| B6.3 | Confuses them | |||||||

| B7. The existing fixture serves its purpose on the selected streets: | ||||||||

| B7.1 | Yes, it is available and well maintained | |||||||

| B7.2 | Available but not functioning well | |||||||

| B7.3 | Very limited fixture or not available | |||||||

| B8. The lighting in the current commercial streets sufficient (at night): | ||||||||

| B8.1 | Very sufficient in most street parts | |||||||

| B8.2 | In some parts only, others are dark | |||||||

| B8.3 | Not Sufficient at all | |||||||

| B9. Local activities such as (Groceries, barbers, sewing shops, Fish and chicken, Local restaurants, and cafes) increase the livability of commercial streets: | ||||||||

| B9.1 | Yes, very much | |||||||

| B9.2 | Some of these activities will affect street cleanness but are still needed | |||||||

| B9.3 | No, not important | |||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| C1-Sociability Dimension | ||||||||

| No. | Sociability parameters | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | ||

| C1-1: Social design and Activities | C1.1.1 | Commercial streets are a good place to meet people. | ||||||

| C1.1.2 | People’s density increases when commercial streets hold diverse activities and are well distributed. | |||||||

| C1.1.3 | Active streets include activities suitable for all ages and genders. | |||||||

| C1.1.4 | Placing cafes and restaurant in street enhance people’s interaction. | |||||||

| C1.1.5 | The availability of informal shops makes streets more useable. | |||||||

| C1-2: Quality of Street | C1.2.1 | People are attracted to visibly connected sidewalks and easily cleared building parts. | ||||||

| C1.2.2 | People feel captivated by a street as inside and outside shops are visually connected and transparent. | |||||||

| C1.2.3 | People’s interaction with the storefronts increases as the number of entrances in each segment increases. | |||||||

| C1.2.4 | Street fixture availability on sidewalks improves staying. | |||||||

| C1.25 | Usually, people use and buy from clean and well-maintained streets. | |||||||

| C1-3: Qualified Commercial Street (Economic) | C1.3.1 | Lighting in streets and storefronts affects positively staying and use at night. | ||||||

| C1.3.2 | Green spaces and trees, enhance staying more in street. | |||||||

| C1.3.3 | Functions such as bakeries and cloth shops activate the street. | |||||||

| C1.3.4 | Extended activities at night effects positively the use of the streets. | |||||||

| C1.3.5 | People purchase from streets with mixed uses more than others. | |||||||

| C1.3.6 | Local activities enhance expending more time. | |||||||

| C1.3.7 | Street adaptability for many different activities makes it an active and sociable place. | |||||||

| C2-Physical Setting Dimension | ||||||||

| items | No. | C2-1: Physical Setting parameters (Architecture and Design) | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | |

| C2-1: Architecture and Design Physical Setting | C2-1-1: Building Physical Setting | C2.1.1.1 | When Building height and street width are compatible with human scale, it will create a positive enclosure. | |||||

| C2.1.1.2 | Clear delineation of building edges with sidewalks enhances pedestrian walking. | |||||||

| C2.1.1.3 | Direct building entrances to sidewalks are easier to use and ease the buying process. | |||||||

| C2.1.1.4 | Buildings with the same heights on both sides give a unified atmosphere and attract people. | |||||||

| C2.1.1.5 | The extra projection of the building block conflicts with street inclusiveness. | |||||||

| C2-1-2: Street Design Physical Setting | C2.1.2.1 | The number of street lanes affects connecting the two sides. | ||||||

| C2.1.2.2 | The physical and visual connection of the two sides eases movement and interaction. | |||||||

| C2.1.2.3 | Special needs elements and fixture increase street useability. | |||||||

| C2.1.2.4 | Street sidewalks are attractive when their width accommodates 4 persons. | |||||||

| C2.1.2.5 | The street is considered legible when its sidewalks contain three design parts (Fixture, Pedestrian, and Frontage Zone). | |||||||

| C2.1.2.6 | An enclosure appears when the height of the buildings on both sides with the street width forms a (1:1) proportion. | |||||||

| C2-1-3: Architectural Physical setting | C2.1.3.1 | diverse architectural styles and shop themes attract shoppers. | ||||||

| C2.1.3.2 | building a connection with the urban context improves its useability. | |||||||

| C2.1.3.3 | If the building materials and colors are unified, it will give a clear appearance. | |||||||

| C2.1.3.4 | Unified architectural elements increase street simplicity. | |||||||

| items | No. | C2-2: Physical Setting parameters (Access and Linkages parameters) | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | |

| C2-2: Accessibility Physical Setting | C2-2-1: Accessibility | C2.2.1.1 | The diversity of street transportation attracts people. | |||||

| C2.2.1.2 | Parking lots are better than parking on street edges. | |||||||

| C2.2.1.3 | clear moving from parking lots to sidewalks makes the street more useable. | |||||||

| C2.2.1.4 | Clarity of access to shops attracts people | |||||||

| C2.2.1.5 | Clear separation between vehicles and pedestrians is useful for good accessibility | |||||||

| C2-2-2: Walkability | C2.2.2.1 | Movement patterns and variety enhance walking. | ||||||

| C2.2.2.2 | Seating on sidewalks with clear movement to shops eases walkability | |||||||

| C2.2.2.3 | The diversity in street activities enhances pedestrian walkability | |||||||

| C2.2.2.4 | Sidewalks connectivity with no obstacles enhances continuity | |||||||

| C2.2.2.5 | The pedestrian movement continues into the night when restaurants and cafes are the main part of street activities | |||||||

| C2-2-3: Spatial Characteristics | C2.2.3.1 | Staying in street is more vitality when building Plinths are continuous and conform to human scale. | ||||||

| C2.2.3.2 | Street delineation whether by trees or fences clarifies the overall street perception. | |||||||

| C2.2.3.3 | A clear transition between street sides supports the spatial organization. | |||||||

| C2.2.3.4 | The availability of resting places in the frontage or fixture zone organizes moving patterns. | |||||||

| C2.2.3.5 | Landscape in a commercial street improves spatial organization. | |||||||

| C2-3: Physical Setting parameters (Environmental) | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | |||

| C2-3: Environmental Physical Setting | C2.3.1 | Using moveable canopies and vendors is important to protect shoppers during the daytime and enhance moving. | ||||||

| C2.3.2 | The presence of shaded spaces refreshes the street environment | |||||||

| C2.3.3 | Green Spaces, planting, and trees have a positive impact on comforting the environment. | |||||||

| C2.3.4 | The use of paving materials that resist heat in summer and bear heavy rains in winter increases their daily street use | |||||||

| C3. Familiarity Dimension | ||||||||

| items | No. | Images | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | |

| C3-1: Familiarity Parameters | C3-1-1: Memory | C3.1.1.1 | The availability of well-maintained greenery is important for attracting pedestrians. | |||||

| C3.1.1.2 | sufficient lighting on sidewalks creates a positive image for the street at night. | |||||||

| C3.1.1.3 | Memorizing architectural styles in the street creates a positive image. | |||||||

| C3.1.1.4 | Images memory will increase as the street contains a traditional style. | |||||||

| C3.1.1.5 | Local restaurants, local food carts, and activities activate a positive image and attract shoppers. | |||||||

| C3.1.1.6 | A sense of identity will be generated when historical elements are added to the building facade. | |||||||

| C3.1.1.7 | People are attached to commercial buildings with aesthetic characteristics. | |||||||

| C3-1-2: Safety | C3.1.2.1 | Pedestrians feel safe and protected when the edge between the street and the sidewalks is clearly defined. | ||||||

| C3.1.2.2 | Ease of communication between pedestrians and cars by providing adequate protection will attract people and create a positive image. | |||||||

| C3.1.2.3 | Clear crossing points and traffic lights are essential in safe streets. | |||||||

| C3.1.2.4 | Availability of Curbs (edging stone or pavement raised path), bollards, and Guard Railings, different colors or levels as separation, is important to feel safe in the pedestrian zone. | |||||||

| C3.1.2.5 | Reducing speed either by dumper ramp or changing materials, changing or adding features generates a sense of safety. | |||||||

| C3-1-3: Comfort | C3.1.3.1 | You would feel comfortable when Parking is close to shops and easy to reach. | ||||||

| C3.1.3.2 | Pavement material quality is an essential element for accommodating walking and different activities. | |||||||

| C3.1.3.3 | Physical separation such as trees and fences are significant elements in comforting people. | |||||||

| C3.1.3.4 | Sidewalks with suitable widths encourage walking and feeling comfortable. | |||||||

| C3.1.3.5 | People are attracted to active well-designed frontage areas with sitting areas and diverse activities. | |||||||

| C3.1.3.6 | Quality of maintenance and cleanness has a great impact on creating comfort place. | |||||||

| C3.1.3.7 | The presence of cyclists refreshes the commercial street. | |||||||

| items | No. | C3-2: Sense of Place (SOP) parameters | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | |

| C3-2: Linked to Street, Identity, Qualified Street | C3.2.1 | The feeling of belonging to the street increases when the general atmosphere is attractive and walkable. | ||||||

| C3.2.2 | Cultural events available on the streets improve the sense of place. | |||||||

| C3.2.3 | The proportional relation between street width and building height creates a complete canyon and a unified sense of place. | |||||||

| C3.2.4 | Well-known street landmarks create mental images and generate a sense of place. | |||||||

| C3.2.5 | When the street owns local amenities and value, it will improve social relations. | |||||||

| C3.2.6 | The possibility to sit and eat is one of the needed characteristics in enhancing social bonding. | |||||||

| C3.2.7 | A sense of belonging will raise when streets include a unified architectural language. | |||||||

| C3.2.8 | Integration of activities, functional diversity, and pedestrian density gives a sense of belonging. | |||||||

| C3.2.9 | Moderate movement for cars enhances the feeling of a sense of belonging. | |||||||

| ||||||||

| This section assessing Livability in commercial streets will ease the relationship between the two parts (placemaking and livability). | ||||||||

| No. | D. Livability | Totally Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally Agree | ||

| D1 | Diverse activities in commercial streets enhance the creation of a livable place. | |||||||

| D2 | Restaurants and cafes are an essential part of livable commercial streets. | |||||||

| D3 | There is a good feeling of everyday life on Erbil’s Commercial Streets. | |||||||

| D4 | Livability in commercial streets will rise when it holds a mix of formal and informal activities. | |||||||

| D5 | Livable streets are obtainable when the frontage zone is active with amenities and accommodates mixed uses. | |||||||

| D6 | When street design accommodates the movement of both cars and pedestrians more livable it will be. | |||||||

| D7 | The more the width of the sidewalk the more livable streets. | |||||||

| D8 | Connecting street to urban contexts increases livability performance. | |||||||

| D9 | The unified architectural style in street makes it more livable. | |||||||

| D10 | Commercial streets are more livable when they are accessible. | |||||||

| D11 | movement patterns and variety enhance walking and livability. | |||||||

| D12 | Streets would be more livable when their link to the urban form is legible. | |||||||

| D13 | Planting, trees, landscaping availability, and street fixture, have a positive impact on creating livable streets. | |||||||

| D14 | When a commercial street generates a sense of safety, it will attract people and be more livable. | |||||||

| D15 | Reducing and controlling car speed will raise livability on commercial streets. | |||||||

| D16 | A clean and well-maintained street is more livable and useable. | |||||||

| D17 | Negative, unused, or neglected spaces will lower the street’s livability. | |||||||

References

- Rahman, N.A.; Shamsuddin, S.; Ghani, I. What Makes People Use the Street? Towards a Liveable Urban Environment in Kuala Lumpur City Centre. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, D. Livable Streets: Protected Neighborhoods? Ann. Am. Acad. Politi-Soc. Sci. 1980, 451, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.; Appleyard, D. Toward an Urban Design Manifesto. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1987, 53, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthya, K.; Furlan, R.; Ellath, L.; Esmat, M.; Al-Matwi, R. Place-Making of Transit Towns in Qatar: The Case of Qatar National Museum-Souq Waqif Corridor. Designs 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clos, J. The City at Eye Level: Lessons for Street Plinths. 2016. Available online: https://thecityateyelevel.com/app/uploads/2018/06/eBook_The.City_.at_.Eye_.Level_English.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://umranica.wikido.xyz/repo/7/75/Cities_For_People_-_Jan_Gehl.pdf. (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Kent, F.; Project of Public Spaces (PPS). [email protected] OR 212.620.5660. 2020. Available online: https://www.pps.org/category/placemaking (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1st ed.; Random House: Totonto, ON, Canada, 1961; Vintage Books. New York: Urban Renewal—United States.3. Urban Policy—United States I. TitleHT167.J33 1992; Available online: https://www.buurtwijs.nl/sites/default/files/buurtwijs/bestanden/jane_jacobs_the_death_and_life_of_great_american.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Non-profit foundation. Placemaking Week Europe. 27 September 2022. Available online: https://placemaking-europe.eu/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Nohra, R.; Salha, C. Placemaking: Putting Life and Soul into Neighborhood Spaces; Hospitality News Middle East, 2 July 2018. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynewsmag.com/placemaking-putting-life-and-soul-into-neighborhood-spaces/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Mohamed, A.M.; Samarghandi, S.; Samir, H.; Mohammed, M.F. The Role of Placemaking Approach in Revitalising AL-ULA Heritage Site: Linkage and Access as Key Factors. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Norfolk District Council. 2023. Available online: https://designguide.north-norfolk.gov.uk/getting-started/the-value-of-placemaking/ (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Nouri, A.S.; Costa, J.P. Placemaking and climate change adaptation: New qualitative and quantitative considerations for the “Place Diagram”. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemak. Urban Sustain. 2016, 10, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, P.J.; Ellery, J.; Borkowsky, M. Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2020, 4, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavampour, E.; Vale, B. Revisiting the “Model of Place”: A Comparative Study of Placemaking and Sustainability. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backen, J. The Value of Placemaking; The City at Eye Level Asia, 4 November 2020. Available online: https://thecityateyelevel.com/stories/the-value-of-placemaking/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Pike, O.M.; Durney, M. Urban Design Manual A best practice guide A companion document to the Guidelines for Planning Authorities on Sustainable Residential Development in Urban Areas. Ireland and across Europe, May 2009. Available online: https://www.opr.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1999-Urban-Design-Manual-1.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Al-Kodmany, K. High-Rise Buildings Placemaking in the High-Rise City: Architectural and Urban Design Analyses. Int. J. High-Rise 2013, 2, 153–169. Available online: https://www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- National Associations of Realtors. Placemaking: Big Impacts, Small Towns. 13 January 2020. Available online: https://www.nar.realtor/blogs/spaces-to-places/placemaking-big-impacts-small-towns (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Aras an Chontae. Urban Centres & Placemaking 7. Mullingar, Mount Street. Available online: https://consult.westmeathcoco.ie/en/consultation/draft-westmeath-county-development-plan-2021-2027/chapter/07-urban-centres-and-place-making (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction, 13th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Carlton, Australia, 2004; Available online: https://docplayer.net/87556924-Place-a-short-introduction-tim-cresswell-ij-blackwell-l-publishing.html (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City, 20th ed.; The M.I.T. Press: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Aravot, I. Back to Phenomenological Placemaking. J. Urban Des. 2002, 7, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toolis, E.E. Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 59, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D.; Sowers, J. Key Texts in Human Geography. In Place and Placelessness, Edward Relph (1976); SAGE Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryfield, F.; Cabana, D.; Brannigan, J.; Crowe, T. Conceptualizing ‘sense of place’ in cultural ecosystem services: A framework for interdisciplinary research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 36, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]