Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections lead to prolonged hospital stays, increased treatment costs, spread of multidrug-resistant microorganisms, and mortality [

1]. While multidrug-resistant microorganisms are encountered with increasing frequency in clinical practice, the effective antibiotic options and especially those against multidrug resistant Gram-negative microorganisms are scarce. Prevention of healthcare-associated infections is the mutual duty of all hospital employees. The common target audience of the current guidelines for the prevention of these healthcare-associated infections is represented by healthcare workers. However, the visitors and caregivers are also important in two respects in hospital infections; they may become ill as a result of an infection that is transmitted from the patient they are accompanying/visiting, or they may carry their infection to the patient they have visited or the other patients in the unit [

2,

3]. Behavioral protocols for visitors and caregivers that aim to prevent healthcare-associated infections are still not available. Hand hygiene is the most effective and inexpensive method in this regard. The World Health Organization (WHO) has described 5 main moments for hand hygiene maintenance: before and after touching a patient, after touching the patient surroundings, before a clean/aseptic procedure, and after a body fluid exposure risk. These recommendations are aimed at healthcare professionals. There are no clear recommendations on how often and in what situations the visitors/caregivers should maintain hand hygiene.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was recommended not to accept visitors to the units of COVID-19 patients, except for essential caregivers who assist in the care of patients who cannot be self-sufficient [

4]. Patient visits were prohibited in Turkish COVID-19 units and other hospital units after the first COVID-19 case was seen in Turkey [

5]. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, patient visits were an important tradition in Turkey and every patient would have several visitors. Patient visits were resumed by June 2022 after the COVID-19 case rate significantly decreased and life had returned to normal. The aim of this study, which was conducted in the pre-pandemic period, was to determine the behavior of the visitors and to determine possible behavior that would contribute to the transmission of pathogenic microorganisms, in order to provide suggestions for visitors in the post-pandemic period.

Methods

This study was conducted at the inpatient units of Yenimahalle Training and Educational Hospital in Ankara, Turkey between 1 October 2019 and 30 October 2019. The Yenimahalle Training and Educational Hospital has 260 beds. The study was approved by the Yenimahalle Training and Educational Hospital’s Ethics Committee and a written informed consent form was signed by the subjects.

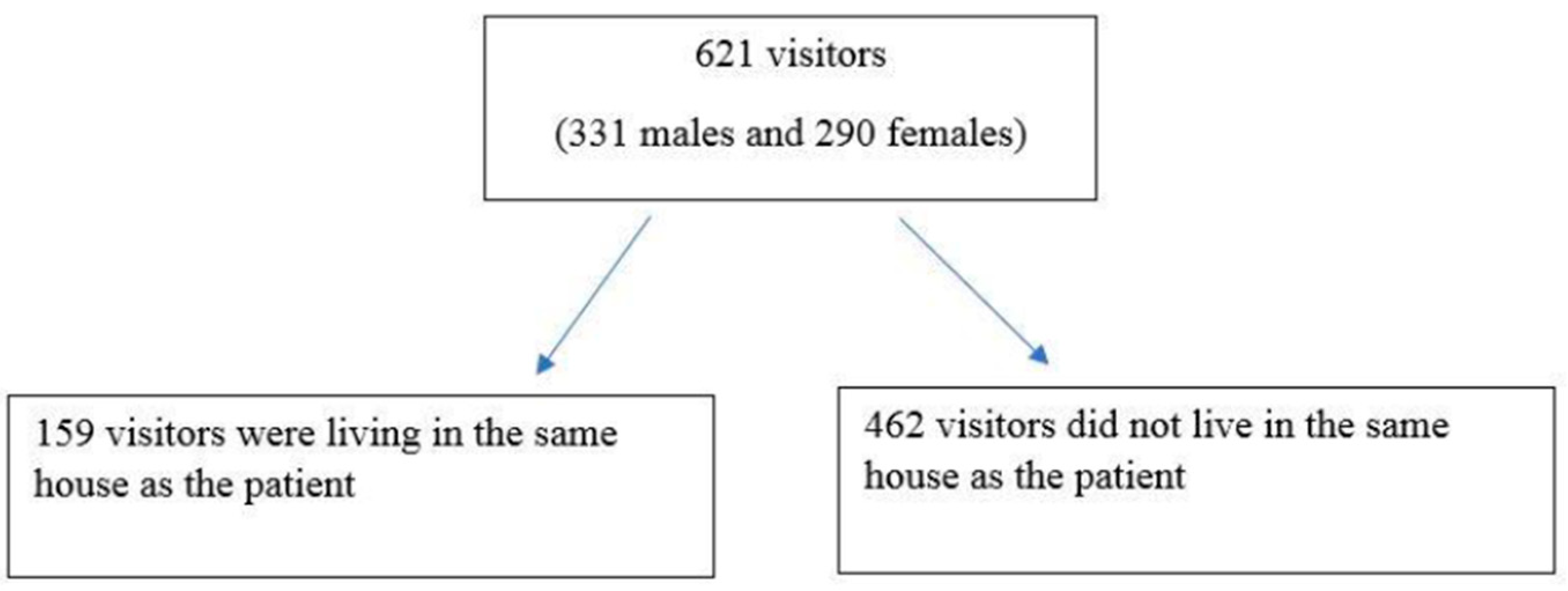

A sink and soap are present in the bathroom in every patient room. There are also alcohol-based hand rubs (AHR) placed out of the reach of children inside the rooms. The visitors who came to visit the inpatients during visiting hours were included in the study while caregivers staying with the patients were not included. All visitors were invited to participate without any selection criteria. Visitors were not accepted for the patients in isolation according to the hospital rules and the survey was therefore administered only to the visitors of the patients who were not in isolation. Survey administration was performed with the face-to-face method at the end of their visitation in the hospital and only visitors who agreed to participate were included in the study.

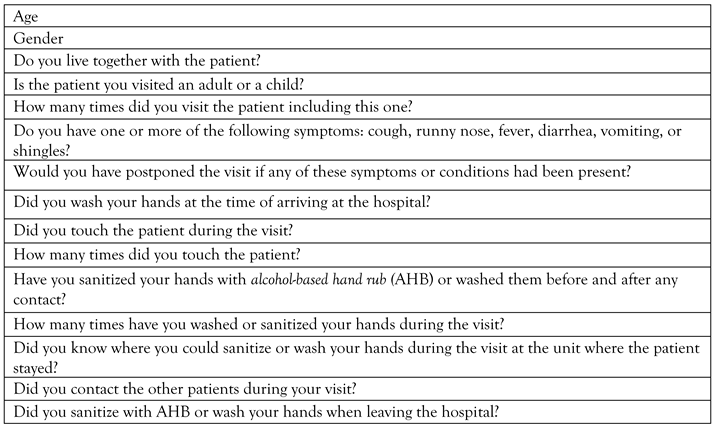

The survey consisted of 13 questions regarding the behavior of the patient visitors (

Table 1). The questions covered the following: (1) demographic features; (2) whether the visitor lived together with the patient; (3) whether the patient was a child or an adult; (4) the number of visits including the current one conducted for the same patient; (5) whether the visitor was currently experiencing one or more of the following: cough, runny nose, fever, diarrhea, vomiting, or shingles; (6) whether the visit would have been postponed if any of these symptoms or conditions had been present; (7) whether the visitor had washed his/her hands at the time of arriving to the hospital; (8) whether the patient had been touched during the visit; (9) the number of times the patient had been touched; (10) whether the hands had been sanitized with alcohol-based hand rub (AHB) or washed before and after the contact if present; (11) the number of times the hands had been washed or sanitized during the visit; (12) whether the visitor knew where he/she could sanitize or wash his/her hands during the visit at the unit where the patient stayed; (13) whether contact had taken place with the other patients; (14) whether the hand had been sanitized or washed when leaving the hospital.

The visitor was accepted to have performed complete hand hygiene during the visit if all three of the following steps had taken place: (i) washing the hands when arriving at the hospital; (ii) washing/sanitizing the hands before and after contact or no contact with the patient during the visit; (iii) washing the hands when leaving the hospital. The visitors were divided into two groups according to the whether all three of the hand hygiene practices had been performed (compliant group) or one or more of these steps had been skipped (non-compliant group). These two groups were compared according to the demographic characteristics and the responses to the questionnaire. The SPSS Statistics 25.0 software (IBM Corp., USA) was used for analyzing the data. The independent samples t-test was used to compare the means of the groups, and the Chi square test was used for categorical variables.

Discussion

About half of the visitors in this study did not maintain hand hygiene. Compliance with hand hygiene was not affected by age, gender, living in the same house as the visited patient, or visiting an adult or pediatric patient. One-third of the visitors did not think they should delay their visit even if they had infectious symptoms.

Hand hygiene is at the forefront of preventive measures for healthcare-associated infections. The contamination state of the hands of patients or visitors and its role in the transmission of healthcare-associated infections are not clearly known. Pathogenic organisms have been frequently detected on the hands of acute care patients [

6,

7]. Pathogenic microorganisms have also been found on the hands of visitors who came to visit intensive care patients and did not perform hand hygiene after the visit, while no pathogenic microorganisms were found in those who performed hand hygiene [

8]. It is not clear in which situations visitors should ensure hand hygiene in the current guidelines. The expert opinion is that visitors should wash their hands immediately after entering and leaving the patient’s room [

3]. Ideally, visitors should ensure hand hygiene before and after each contact with the patient. However, this may not be possible in cases where the visitors come into contact with the patient numerous times, as in pediatric patients [

9,

10]. Studies involving visitor hand hygiene compliance have evaluated the practice in various different situations, probably because there is no consensus on the hand hygiene of visitors. The rate of hand sanitization by the visitors on entering the hospital has been reported as 3.71% [

11]. In another study, the rate of hand hygiene during the period from entering the patient’s inpatient unit and room to exiting the unit was found to be 9.7% [

12]. Young visitors were found to have higher compliance with hand hygiene [

11]. The self-reported hand hygiene rates of the visitors have been found to be higher than the actually observed rates [

13,

14]. The higher hand hygiene compliance rates in our study compared to those reported in the literature may be due to the fact that this was a survey study with no observation. No difference was found between the compliant and non-compliant groups in terms of age in the current study. It is possible to predict that an increase in the number of contacts makes it difficult to comply with hand hygiene before and after each contact, but there was again no difference in the number of contacts between the two groups in our study.

Several studies have reported that carrying out a short verbal information session on hand hygiene at the hospital entrance ensures a very significant increase in hand hygiene compliance [

12,

15]. Compliance with hand hygiene has also been reported to increase significantly when the hand hygiene area is placed in a more visible location [

11,

16]. Hand hygiene compliance, which was as low as 0.4% among the visitors, has been reported to have improved significantly with the placement of alcohol-based hand sanitizers where they are clearly visible and placing the “Clean Hands Save Lives” banner nearby [

18]. The rate of knowing where to wash/sanitize hands was high in both groups in this study (70% and 82.6%, respectively). However, the rate of those who did not know where to wash/sanitize their hands was higher in the non-compliant group. The number of visits was also higher in the compliant group. The repeated visits may have increased knowledge about the importance of hand hygiene in this group.

Individuals with complaints of upper respiratory tract infection, cough, runny nose, diarrhea, or vomiting are suggested to avoid visiting patients at the hospital. This is one of the most important factors to consider, especially in pediatric units. A visitor transmitting an existing infection to the patient, especially a pediatric patient, could create confusion regarding the patient’s clinical picture and lead to unnecessary laboratory investigations and treatments [

2,

3,

17]. In the current study, one-tenth of the participants had at least one infection-related symptom, and one-third stated that they would not delay the visit if they had such symptoms. In the pre-pandemic period, visitors could normally go to the patient’s room during the visiting hours of hospitals without being queried about any infection symptoms. The COVID-19 pandemic may have increased the awareness of individuals about staying at home, maintaining a social distance, and not meeting with other people unless necessary during their infectious period, so as not to infect others with their own infection. On the other hand, the belief that these measures are only valid for COVID-19 may lead to a rapid return to old habits after the pandemic. Therefore, the results of our study show that visitors should be queried about symptoms at the entrance of the hospital regardless of the pandemic situation.

This study had several limitations. First, this study was a survey-based study without observation. The participants may have reported a higher rate than the actual hand hygiene compliance rate. Second, our study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic may have significantly increased the level of knowledge about hand hygiene and protection from infections. Therefore, our study data may not be closely reflective of the current situation.

Visitors should avoid contact with other patients, as they may become vectors in the transmission of infection to them. It is therefore undesirable for the visitor to come into contact with other patients. Very few of the visitors in the current study reported contact with the other patients during their visit, indicating a high level of awareness on this issue.