Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of (4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine through Commercially Available Palladium Catalyst: Synthesis, Optimization and Their Structural Aspects Identification through Computational Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals Used for Coupling of 5-(4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine with Boronic Acid

2.2. Procedure for Synthesis of 5-([17]-4-yl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine

2.3. Computational Methods

3. Results

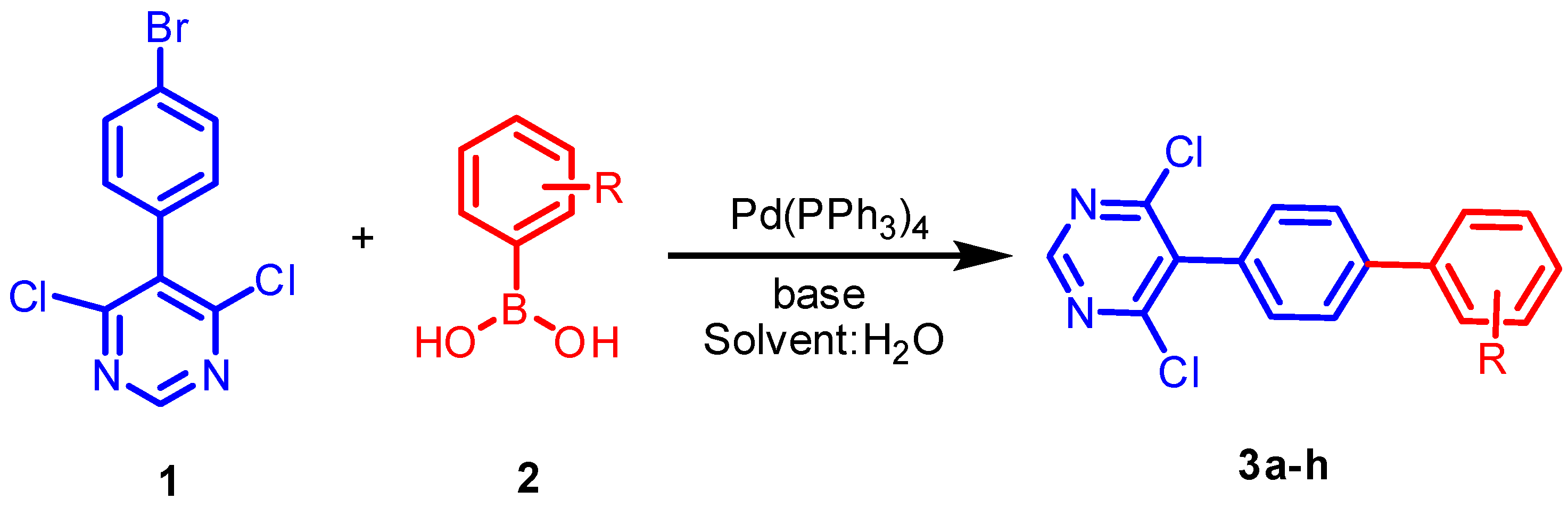

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Computational Studies

3.3.1. Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) Analysis and Hyperpolarizability

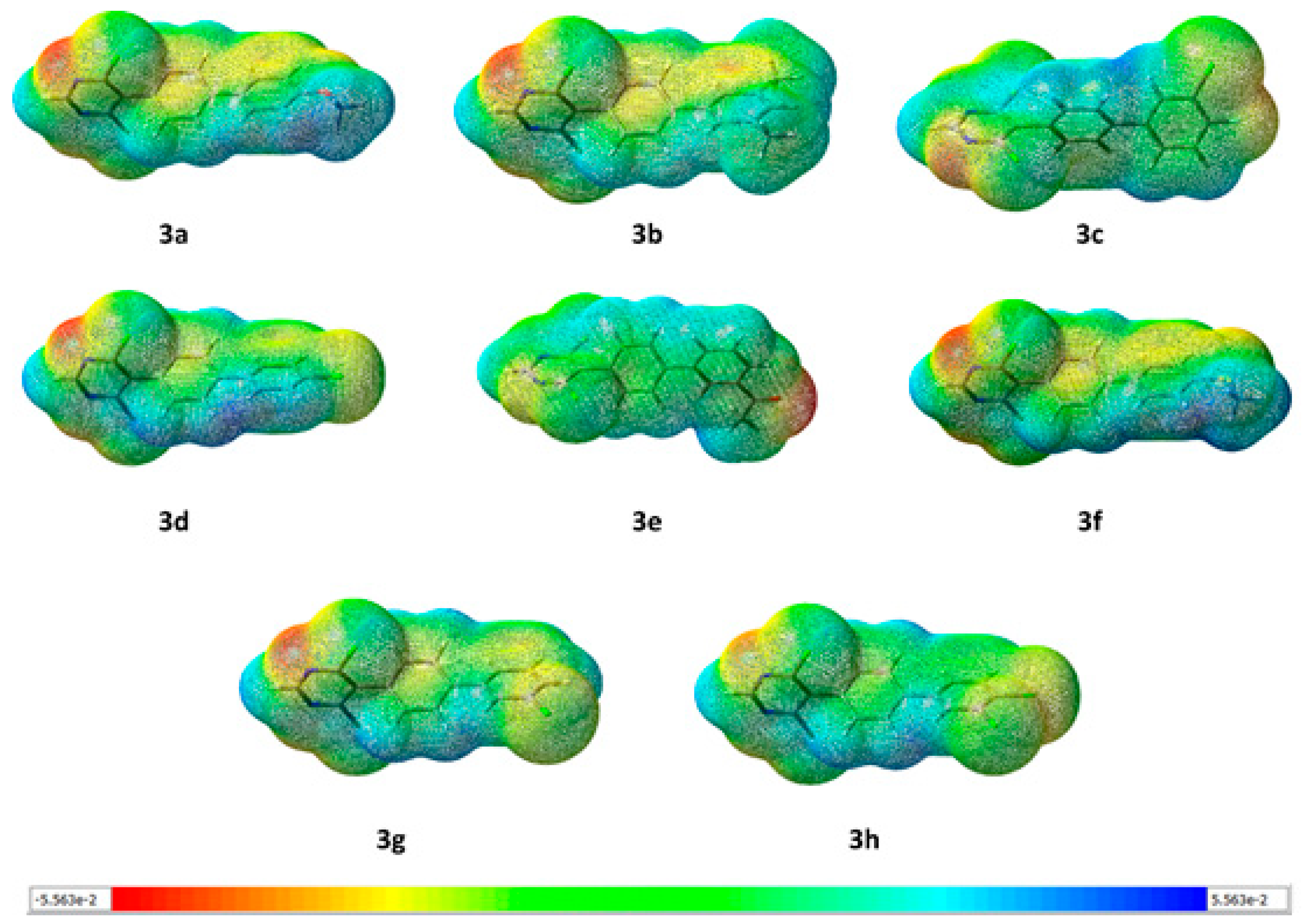

3.3.2. Molecular Electrostatic Potential

3.3.3. Conceptual DFT Reactivity Descriptors

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naik, T.; Chikhalia, K. Studies on synthesis of pyrimidine derivatives and their pharmacological evaluation. J. Chem. 2007, 4, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.L.; Rosa, J.M.; Gadotti, V.M.; Goulart, E.C.; Santos, M.M.; Silva, A.V.; Sehnem, B.; Rosa, L.S.; Goncalves, R.M.; Correa, R.; et al. Antidepressant-like and antinociceptive-like actions of 4-(4′-chlorophenyl)-6-(4″-methylphenyl)-2-hydrazinepyrimidine Mannich base in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005, 82, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L.; Lou, L.; Hu, Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 2,4,5-substituted pyrimidine derivatives for anticancer activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalgat, C.M.; Irfan Ali, M.; Ramesh, B.; Ramu, G. Novel pyrimidine and its triazole fused derivatives: Synthesis and investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, B.; Dinda, S.C.; Prasad, Y.R.; Rao, A.V. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some new 2, 4,6-trisubstituted pyrimidines. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Chem. 2012, 2, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Slusarczyk, M.; Serpi, M.; Pertusati, F. Phosphoramidates and phosphonamidates (ProTides) with antiviral activity. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2018, 26, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgawad, M.A.; Bakr, R.B.; Azouz, A.A. Novel pyrimidine-pyridine hybrids: Synthesis, cyclooxygenase inhibition, anti-inflammatory activity and ulcerogenic liability. Bioorganic Chem. 2018, 77, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, H.M.; Shaaban, O.G.; Rizk, O.H.; El-Ashmawy, I.M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thieno [2′,3′:4,5]pyrimido[1,2-b][1,2,4]triazines and thieno[2,3-d][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines as anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 62, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Khan, S.I.; Tekwani, B.L.; Ponnan, P.; Rawat, D.S. 4-Aminoquinoline-pyrimidine hybrids: Synthesis, antimalarial activity, heme binding and docking studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 89, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, C.O. 100 years of the biginelli dihydropyrimidine synthesis. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 6937–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, B.Y.; Ahn, J.B.; Kang, S.K.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, J.S.; Ahn, S.K.; Lee, S.J.; Yoon, S.S. Molecular design, synthesis, and hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of novel pyrimidine derivatives having thiazolidinedione. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Agarwal, A.K. Significance and biological importance of pyrimidine in the microbial world. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 2014, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomaker, J.M.; Delia, T.J. Arylation of halogenated pyrimidines via a Suzuki coupling reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 7125–7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, K.; Sinha, B.; Maji, P.; Chattopadhyay, S. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular arylation of pyrimidines: A novel and expedient avenue to benzannulated pyridopyrimidines. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 2751–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi-Nezhad, A.; Zare, A.; Parhami, A.; Soltani Rad, M.N.; Nejabat, G.R. Regioselective N-Arylation of Some Pyrimidine and Purine Nucleobases. Synth. Commun. 2006, 36, 3549–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Hammann, J.M.; Greiner, R.; Knochel, P. Recent Developments in Negishi Cross-Coupling Reactions. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, I.; Mujahid, A.; Rasool, N.; Rizwan, K.; Malik, A.; Ahmad, G.; Shah, S.A.A.; Rashid, U.; Nasir, N.M. Palladium and Copper Catalyzed Sonogashira cross Coupling an Excellent Methodology for CC Bond Formation over 17 Years: A Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H.M.; Rasool, N.; Kanwal, I.; Hashmi, M.A.; Altaf, A.A.; Ahmed, G.; Malik, A.; Kausar, S.; Khan, S.U.D.; Ahmad, A. Synthesis of halogenated [1, 1′-biphenyl]-4-yl benzoate and [1, 1′: 3′, 1″-terphenyl]-4′-yl benzoate by palladium catalyzed cascade C–C coupling and structural analysis through computational approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1222, 128839–128848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, M.; Rasool, N.; Gull, Y.; Nasim, F.U.H.; Zahoor, A.F.; Yaqoob, A.; Kousar, S.; Zubair, M.; Bukhari, I.H.; Rana, U.A. A facile synthesis of new 5-aryl-thiophenes bearing sulfonamide moiety via Pd(0)-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling reactions and 5-bromothiophene-2-acetamide: As potent urease inhibitor, antibacterial agent and hemolytically active compounds. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, S403–S414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, N.; Rasool, N.; Rizwan, K.; Altaf, A.A.; Ali, S.; Malik, A.; Zubair, M.; Akhtar, A.; Kausar, S.; Shah, S.A.A. Efficient synthesis of 2,3-diarylbenzo [b] thiophene molecules through palladium (0) Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and their antithrombolyitc, biofilm inhibition, hemolytic potential and molecular docking studies. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, K.; Rasool, N.; Rehman, R.; Mahmood, T.; Ayub, K.; Rasheed, T.; Ahmad, G.; Malik, A.; Khan, S.A.; Akhtar, M.N. Facile synthesis of N-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(3-bromothiophen-2-yl) methanimine derivatives via Suzuki cross-coupling reaction: Their characterization and DFT studies. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Vorobyeva, E.; Mitchell, S.; Fako, E.; Ortuño, M.A.; López, N.; Collins, S.M.; Midgley, P.A.; Richard, S.; Vilé, G. A heterogeneous single-atom palladium catalyst surpassing homogeneous systems for Suzuki coupling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.D.; Barder, T.E.; Martinelli, J.R.; Buchwald, S.L. A rationally designed universal catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling processes. Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Nelson, D.P.; Jensen, M.S.; Hoerrner, R.S.; Javadi, G.J.; Cai, D.; Larsen, R.D. Palladium-Catalyzed Regioselective Arylation of Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 4835–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Bellomo, A.; Zhang, M.; Carroll, P.J.; Manor, B.C.; Jia, T.; Walsh, P.J. Palladium-Catalyzed direct C–H arylation of 3-(methylsulfinyl) thiophenes. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2522–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.S.; Aires-de-Sousa, J.; Belsley, M.; Raposo, M.M.M. Synthesis of pyridazine derivatives by Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and evaluation of their optical and electronic properties through experimental and theoretical studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, H.; Rasool, N.; Ansari, M.T.; Rizwan, K.; Iqbal, S.; Mahmood, T.; Israr, H.; Ayub, K.; Rasheed, T.; Zareen, S. Selective arylation of phenol protected propargyl bromide via Pd-catalysed suzuki coupling reaction: Synthesis, mechanistic studies by DFT calculations and their pharmacological aspects. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2018, 75, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, G.; Rasool, N.; Ikram, H.M.; Gul Khan, S.; Mahmood, T.; Ayub, K.; Zubair, M.; Al-Zahrani, E.; Ali Rana, U.; Akhtar, M.N. Efficient synthesis of novel pyridine-based derivatives via Suzuki cross-coupling reaction of commercially available 5-bromo-2-methylpyridin-3-amine: Quantum mechanical investigations and biological activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09 Revision D. 01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 77, 3865–3868, reprinted in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104–154123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammi, R.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J. Fast Evaluation of Geometries and Properties of Excited Molecules in Solution: A Tamm-Dancoff Model with Application to 4-Dimethylaminobenzonitrile. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 5631–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Barone, V. Solvent effect on vertical electronic transitions by the polarizable continuum model. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 2427–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Barone, V. Time-dependent density functional theory for molecules in liquid solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 4708–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V. Polarizable dielectric model of solvation with inclusion of charge penetration effects. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 5691–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Scalmani, G.; Rega, N.; Barone, V. New developments in the polarizable continuum model for quantum mechanical and classical calculations on molecules in solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CYLview; Legault, C.Y. Université de Sherbrooke. Available online: http://www.cylview.org (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Lee, D.H.; Choi, M.; Yu, B.W.; Ryoo, R.; Taher, A.; Hossain, S.; Jin, M.J. Expanded Heterogeneous Suzuki—Miyaura Coupling Reactions of Aryl and Heteroaryl Chlorides under Mild Conditions. Adv. Synth. 2009, 351, 2912–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadh, S.M.; Farghaly, T.A.; Abdallah, M.A.; Abdalla, M.M.; El-Aziz, M.R.A. New pyrazoles incorporating pyrazolylpyrazole moiety: Synthesis, anti-HCV and antitumor activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, T.; Mase, T. Direct synthesis of hetero-biaryl compounds containing an unprotected NH2 group via Suzuki–Miyaura reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3573–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, G.; Rasool, N.; Rizwan, K.; Altaf, A.A.; Rashid, U.; Mahmood, T.; Ayub, K. Role of Pyridine Nitrogen in Palladium-Catalyzed Imine Hydrolysis: A Case Study of (E)-1-(3-bromothiophen-2-yl)-N-(4-methylpyridin-2-yl)methanimine. Molecules 2019, 24, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Gelbaum, C.; Campbell, Z.S.; Gould, P.C.; Fisk, J.S.; Holden, B.; Jaganathan, A.; Whiteker, G.T.; Pollet, P.; Liotta, C.L. Pd-Catalyzed Suzuki coupling reactions of aryl halides containing basic nitrogen centers with arylboronic acids in water in the absence of added base. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 15420–15432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fu, Q.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, X.; Fu, H.; Chen, H.; Li, R. Tetraphosphine/palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of heteroaryl halides with 3-pyridine- and 3-thiopheneboronic acid: An efficient catalyst for the formation of biheteroaryls. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 27, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivila, H.G.; Nahabedian, K.V. Electrophilic Displacement Reactions. X. General Acid Catalysis in the Protodeboronation of Areneboronic Acids1-3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 2159–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitulescu, G.M.; Draghici, C.; Olaru, O.T.; Matei, L.; Ioana, A.; Dragu, L.D.; Bleotu, C. Synthesis and apoptotic activity of new pyrazole derivatives in cancer cell lines. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 5799–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivila, H.G.; Reuwer, J.F.; Mangravite, J.A. Electrophilic Displacement Reactions. XVI. Metal Ion Catalysis in the Protodeboronation of Areneboronic Acids1-3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 2666–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.A.; Reid, M.; Leach, A.G.; Campbell, A.D.; King, E.J.; Lloyd-Jones, G.C. Base-Catalyzed Aryl-B(OH)2 Protodeboronation Revisited: From Concerted Proton Transfer to Liberation of a Transient Aryl Anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13156–13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, M.N.; Bibi, A.; Mahmood, T.; Asiri, A.M.; Ayub, K. Synthesis, crystal structures and spectroscopic properties of triazine-based hydrazone derivatives; a comparative experimental-theoretical study. Molecules 2015, 20, 5851–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumrra, S.H.; Kausar, S.; Raza, M.A.; Zubair, M.; Zafar, M.N.; Nadeem, M.A.; Mughal, E.U.; Chohan, Z.H.; Mushtaq, F.; Rashid, U. Metal based triazole compounds: Their synthesis, computational, antioxidant, enzyme inhibition and antimicrobial properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1168, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.K.; Periasamy, N. Calculation of electron affinity, ionization potential, transport gap, optical band gap and exciton binding energy of organic solids using ‘solvation’ model and DFT. Org. Electron. 2009, 10, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.G.; Nichols, J.A.; Dixon, D.A. Ionization Potential, Electron Affinity, Electronegativity, Hardness, and Electron Excitation Energy: Molecular Properties from Density Functional Theory Orbital Energies. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 4184–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Boronic Acid | Solvent: H2O | Base | Percentage Yield [a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 4-methoxy Phenyl | Dry Toluene | K3PO4 | 40% |

| Acetonitrile | 36% | |||

| 1,4-dioxane | 60% | |||

| 3b | 3,5-Dimethyl Phenyl | Dry Toluene | K3PO4 | 70% |

| Cs2CO3 | 80% | |||

| 3c | 3-Chloro-4-fluoro Phenyl | Dry Toluene | Cs2CO3 | Not formed |

| 1,4-dioxane | K3PO4 | Not formed | ||

| 3d | 4-chloro Phenyl | 1,4-Dioxane | K3PO4 | 15% |

| DMF | 20% | |||

| 3e | 3-Acetyle Phenyl | 1,4-dioxane | K3PO4 | 60% |

| 3f | 4-Methyl Thio Phenyl | 1,4-dioxane | K3PO4 | 55% |

| 3g | 3-Chloro Phenyl | 1,4-dioxane | K3PO4 | 25% |

| 3h | 3,4-dicholoro Phenyl | 1,4-dioxane | K3PO4 | 30% |

| Compound | EHOMO | ELUMO | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) | Hyperpolarizability (β) (Hartrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | −6.13 | −1.59 | 4.53 | 6504.69 |

| 3b | −6.51 | −1.60 | 4.91 | 2206.09 |

| 3c | −6.62 | −1.61 | 5.01 | 2417.57 |

| 3d | −6.54 | −1.61 | 4.94 | 2854.76 |

| 3e | −6.69 | −1.81 | 4.88 | 1119.66 |

| 3f | −5.89 | −1.60 | 4.29 | 8971.00 |

| 3g | −6.70 | −1.61 | 5.09 | 1132.95 |

| 3h | −6.64 | −1.65 | 4.99 | 2289.21 |

| Compound | Ionization Potential I (eV) | Electron Affinity A (eV) | Chemical Hardness ƞ (eV) | Electronic Chemical Potential (μ) (eV) | Electrophilicity Index ω (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 6.13 | 1.59 | −2.27 | 3.86 | −3.29 |

| 3b | 6.51 | 1.60 | −2.46 | 4.06 | −3.35 |

| 3c | 6.62 | 1.61 | −2.51 | 4.12 | −3.38 |

| 3d | 6.54 | 1.61 | −2.47 | 4.08 | −3.36 |

| 3e | 6.69 | 1.81 | −2.44 | 4.25 | −3.70 |

| 3f | 5.89 | 1.60 | −2.15 | 3.74 | −3.27 |

| 3g | 6.70 | 1.61 | −2.54 | 4.16 | −3.39 |

| 3h | 6.64 | 1.65 | −2.50 | 4.15 | −3.44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malik, A.; Rasool, N.; Kanwal, I.; Hashmi, M.A.; Zahoor, A.F.; Ahmad, G.; Altaf, A.A.; Shah, S.A.A.; Sultan, S.; Zakaria, Z.A. Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of (4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine through Commercially Available Palladium Catalyst: Synthesis, Optimization and Their Structural Aspects Identification through Computational Studies. Processes 2020, 8, 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8111342

Malik A, Rasool N, Kanwal I, Hashmi MA, Zahoor AF, Ahmad G, Altaf AA, Shah SAA, Sultan S, Zakaria ZA. Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of (4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine through Commercially Available Palladium Catalyst: Synthesis, Optimization and Their Structural Aspects Identification through Computational Studies. Processes. 2020; 8(11):1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8111342

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalik, Ayesha, Nasir Rasool, Iram Kanwal, Muhammad Ali Hashmi, Ameer Fawad Zahoor, Gulraiz Ahmad, Ataf Ali Altaf, Syed Adnan Ali Shah, Sadia Sultan, and Zainul Amiruddin Zakaria. 2020. "Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of (4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine through Commercially Available Palladium Catalyst: Synthesis, Optimization and Their Structural Aspects Identification through Computational Studies" Processes 8, no. 11: 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8111342

APA StyleMalik, A., Rasool, N., Kanwal, I., Hashmi, M. A., Zahoor, A. F., Ahmad, G., Altaf, A. A., Shah, S. A. A., Sultan, S., & Zakaria, Z. A. (2020). Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of (4-bromophenyl)-4,6-dichloropyrimidine through Commercially Available Palladium Catalyst: Synthesis, Optimization and Their Structural Aspects Identification through Computational Studies. Processes, 8(11), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8111342