Numerical and Experimental Results

In this study, a sample distribution network of AKEDAS, which provides electricity distribution services in Kahramanmaras and Adiyaman provinces in southern Turkey, is used for the analysis and simulations. The numerical analysis and optimization are performed in DIgSILENT PowerFactory using the actual distribution feeder model and PV inverter rated data and locations. The operating point analyzed in this manuscript corresponds to the PowerFactory study-time selection of Hour-of-Year 5051–5052 (i.e., 30 July 2021 11:00–12:00) based on the annual time-series profiles. This representative time window was selected to provide a consistent comparison of optimization algorithms under identical system conditions.

Table 1 shows the details about the study time and the validation setup.

AKEDAS, which provides electricity distribution services to a population of 1,672,890 in Kahramanmaras and Adiyaman, operates in distribution region 20, which was privatized by Turkish Electricity Distribution Corporation.

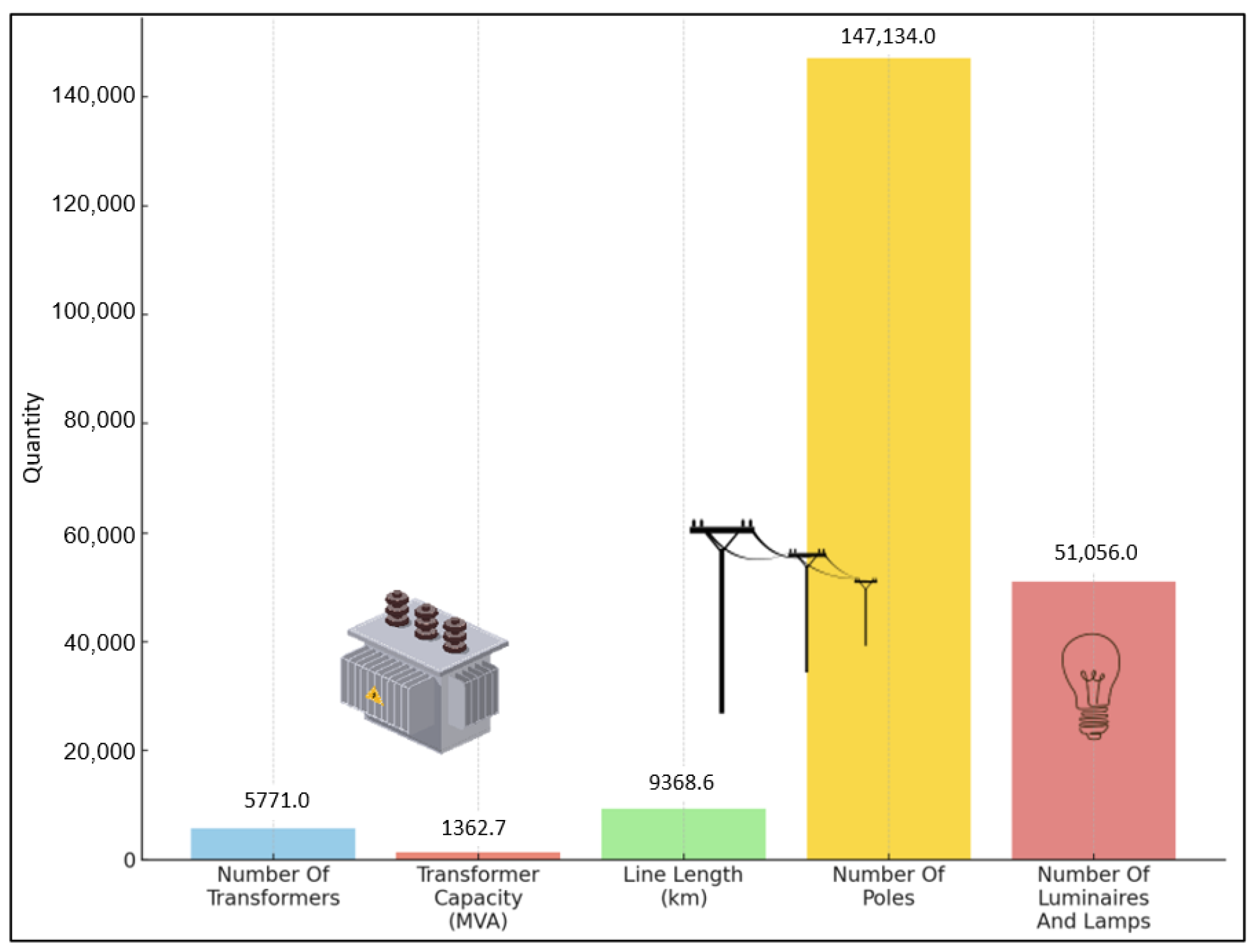

Figure 3 shows the amount of equipment in the electricity distribution network in the Adiyaman region as of 2023. As seen in this figure, there are 5771 transformers connected to AKEDAS in Adiyaman province, where the study was conducted, and their total installed power is 1362.7 MVA. The total line length is 9368.6 km. The total number of poles is 147,134, while the number of armatures and lamps is 51,056.

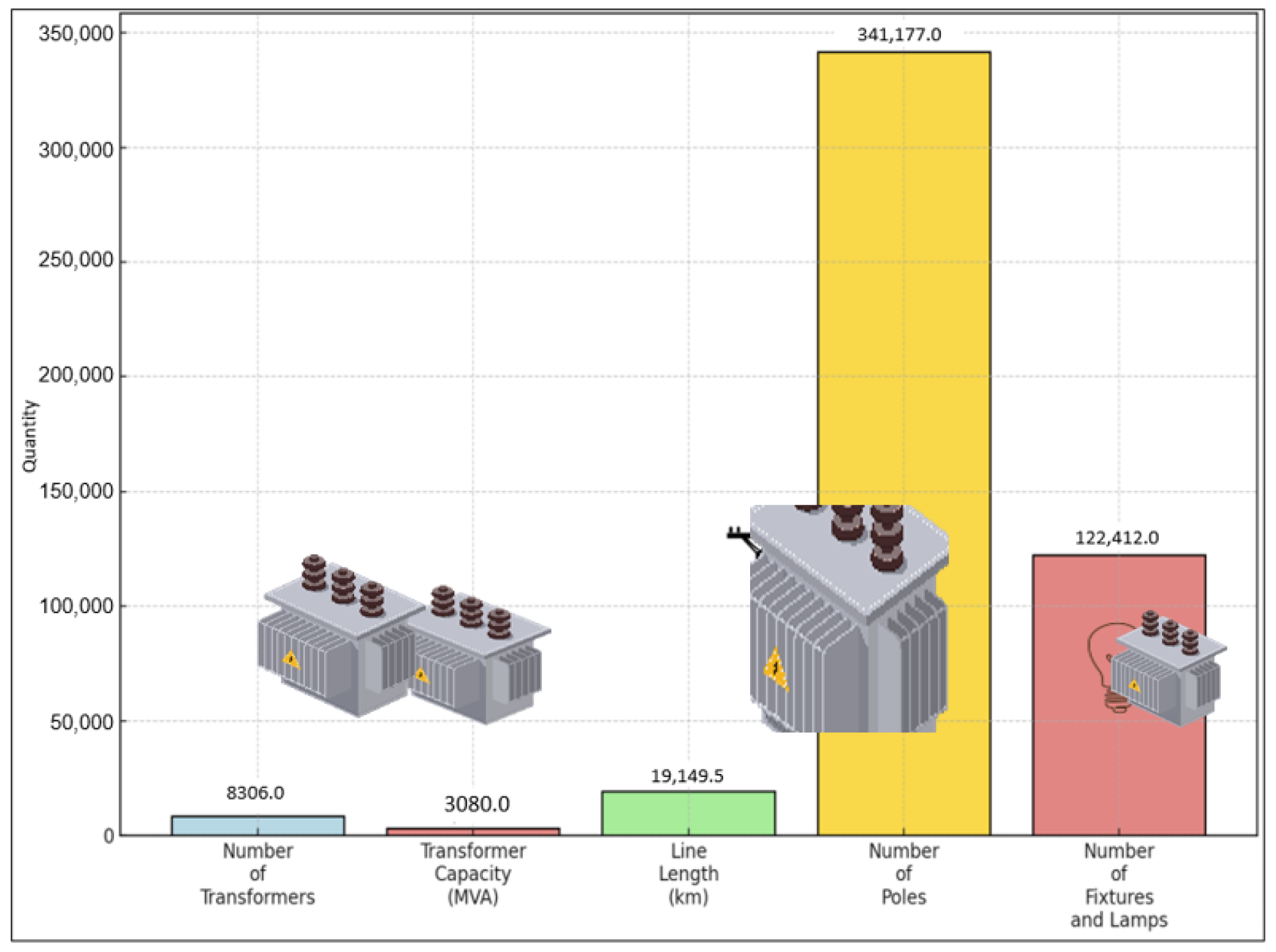

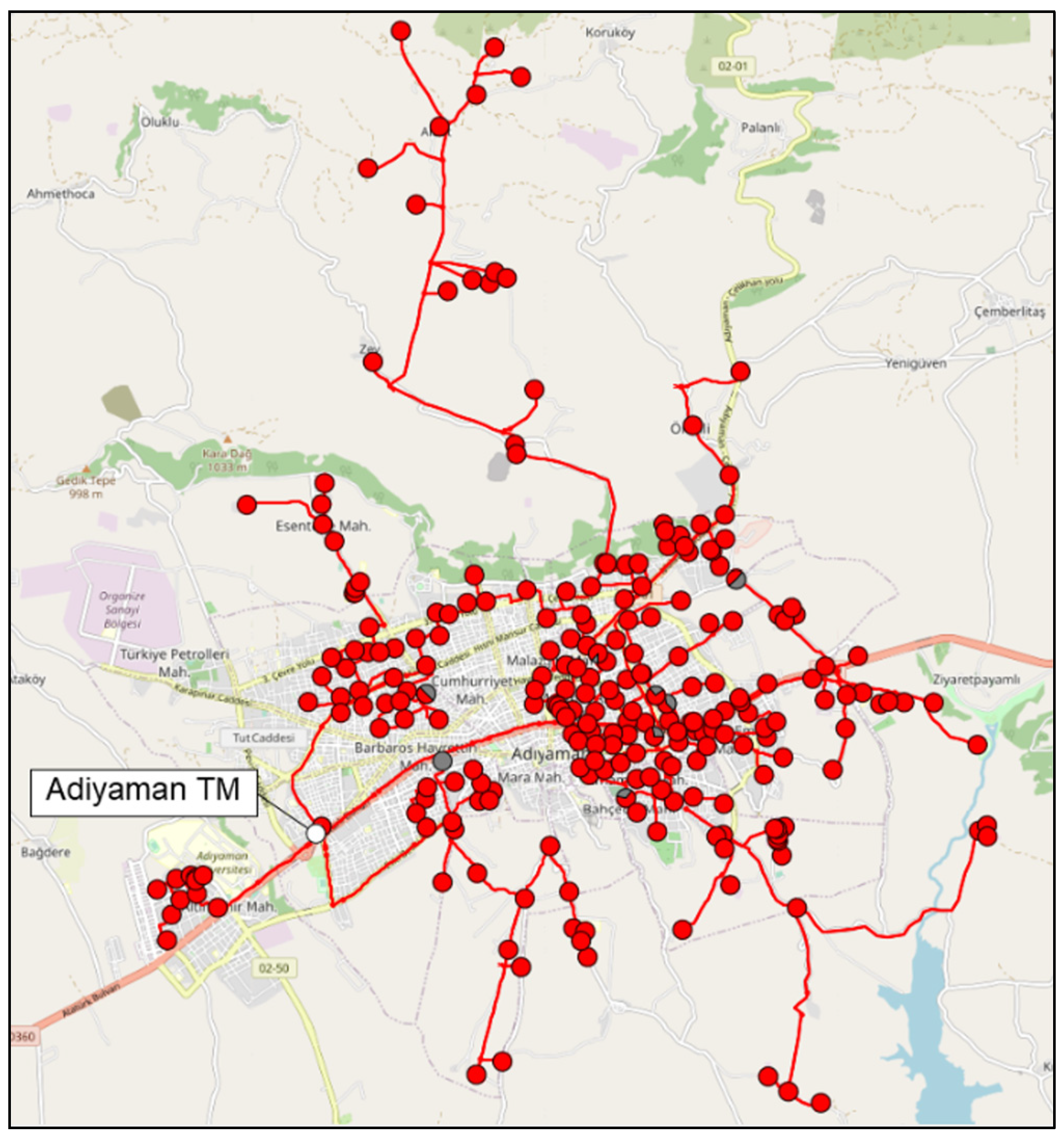

Figure 4 shows the network information and the amount of equipment within AKEDAS in Kahramanmaras. As can be seen in the figure, there are 8306 transformers connected to AKEDAS in Kahramanmaras. The total installed power of these transformers is 3080 MVA, and the total line length is 19,149.50 km. The total number of poles is 341,777, and the number of armatures and lamps is 122,412. In this study, samples taken from the Adiyaman TM1 city feeder were studied. There are 12 PV power plants with an installed capacity of 11.8 MW in this region.

Figure 5 shows the image of Adiyaman TM1 city feeder taken from the geographical information system used in AKEDAS. A simulation study was carried out on the substation in the Adiyaman region and the City1 TM feeder connected to it. A grid connection model was created by integrating the data obtained from the geographical information system with DIgSILENT PowerFactory 2022 software (DIgSILENT GmbH, Gomaringen, Germany). Geographical information system data are processed and embedded in DIgSILENT software. In

Figure 5, the red markers connected to this substation indicate the distribution transformer posts.

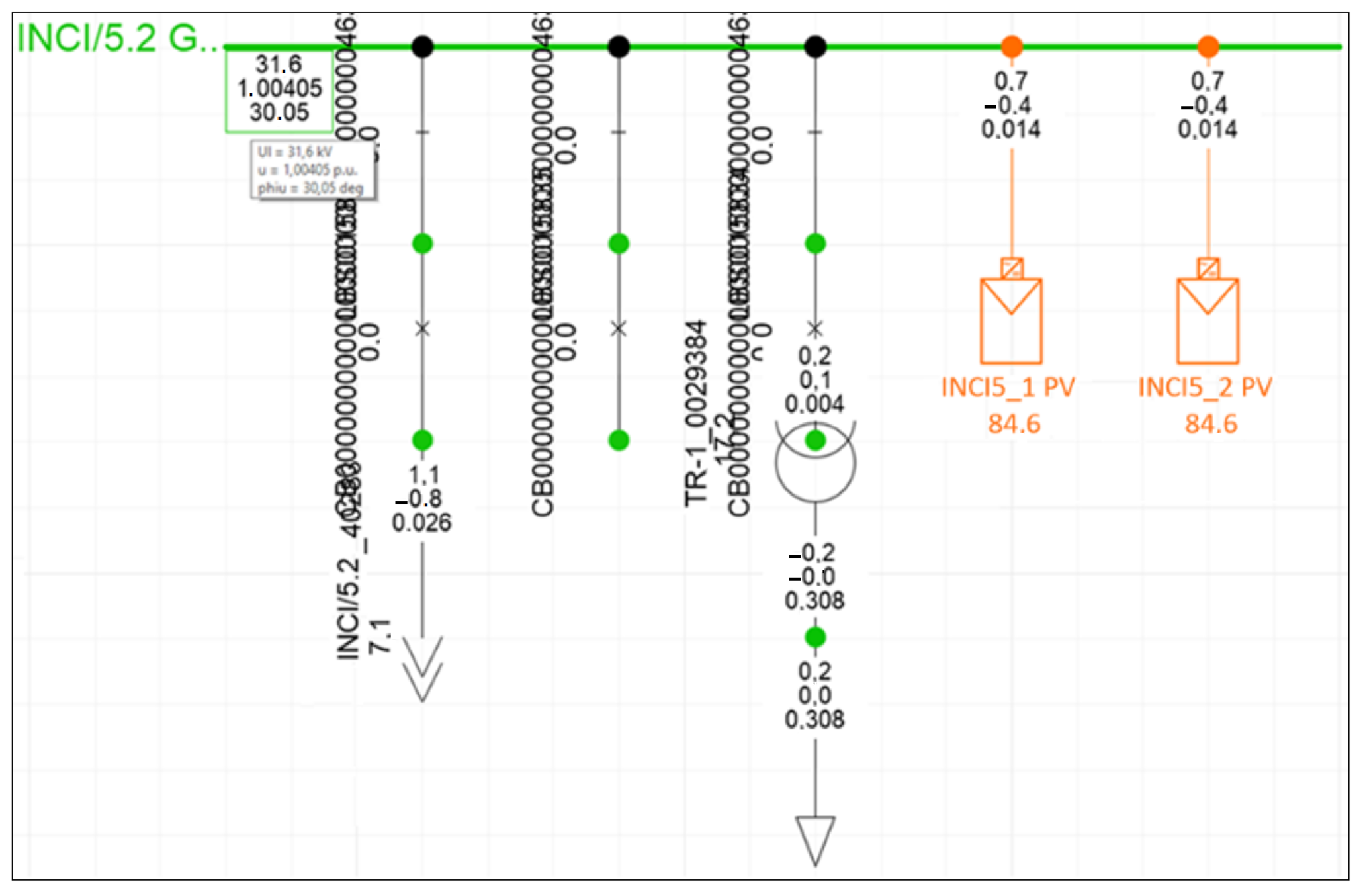

Each of the colors in the simulation has a meaning, and the meaning of these colors as voltage equivalent (as p.u) is seen on the DIgSILENT application. In 258 busbars, where load flow analysis was performed, voltage and angle details were obtained after the analysis. Regarding the simulation, a separate study was carried out for the busbar to which 2 PV power plants are connected. Here, voltage data was analyzed as 1.00405 p.u. and phase-angle information as 30.05 degrees. At the same time, while the active generation of the PV plants is 0.7 MW, the reactive energy support from these 2 plants is −0.4 MVAR. Since the voltage is high on the INCI5_2 PV plant line, the PV plant draws reactive energy from the line to reduce the voltage.

Figure 6 shows the voltage and load information on a sample busbar. As seen in

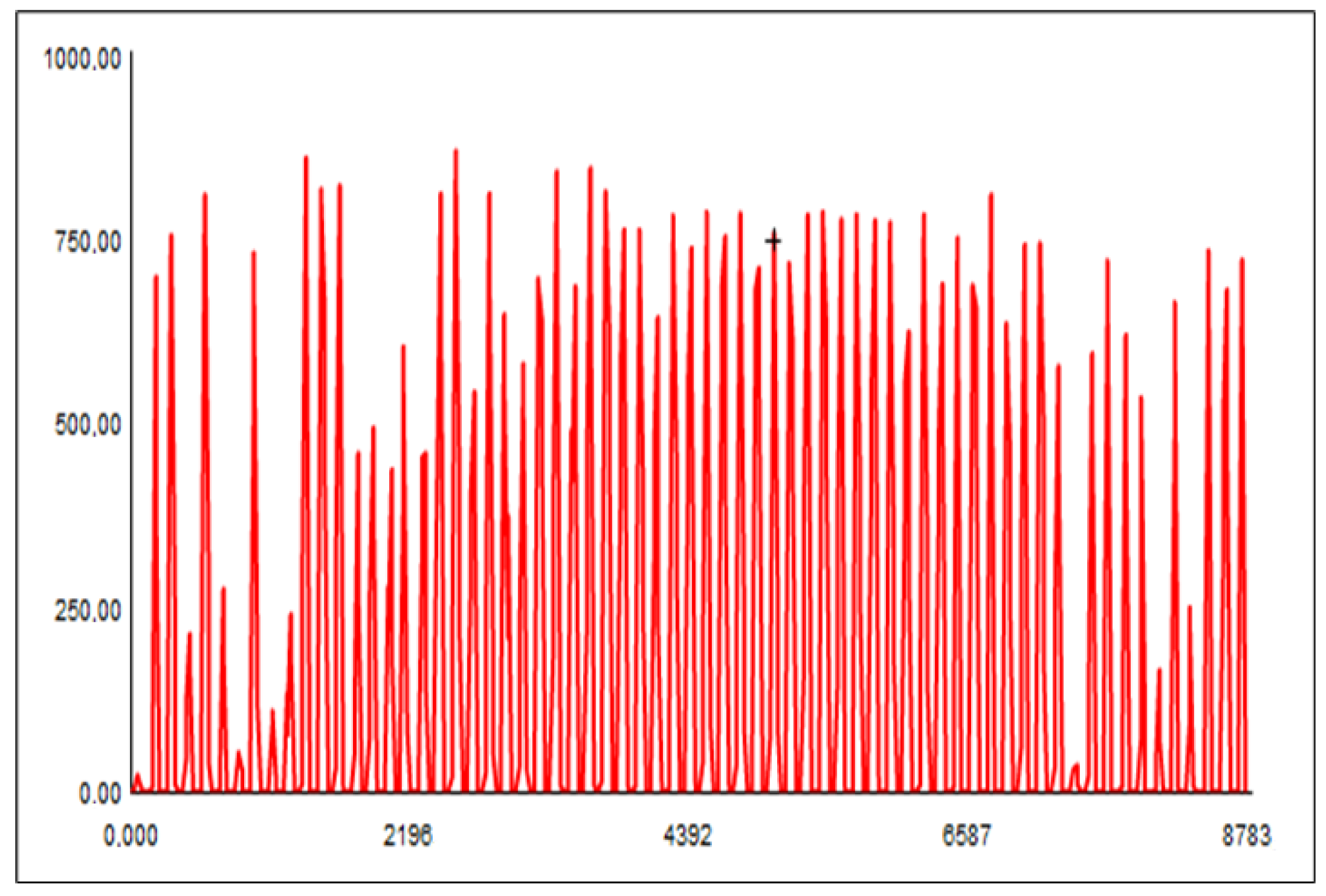

Figure 6, it is possible to access information such as Active Power, Reactive Power, etc., from the LOAD FLOW screen on DIgSILENT for INCI5_2 PV, one of the 2 PV plants taken as an example. The annual load profile of INCI5_2 PV on the DIgSILENT application is shown in

Figure 7.

Table 2 includes the list of the 12 PV plants in the sample grid and their active and reactive power information.

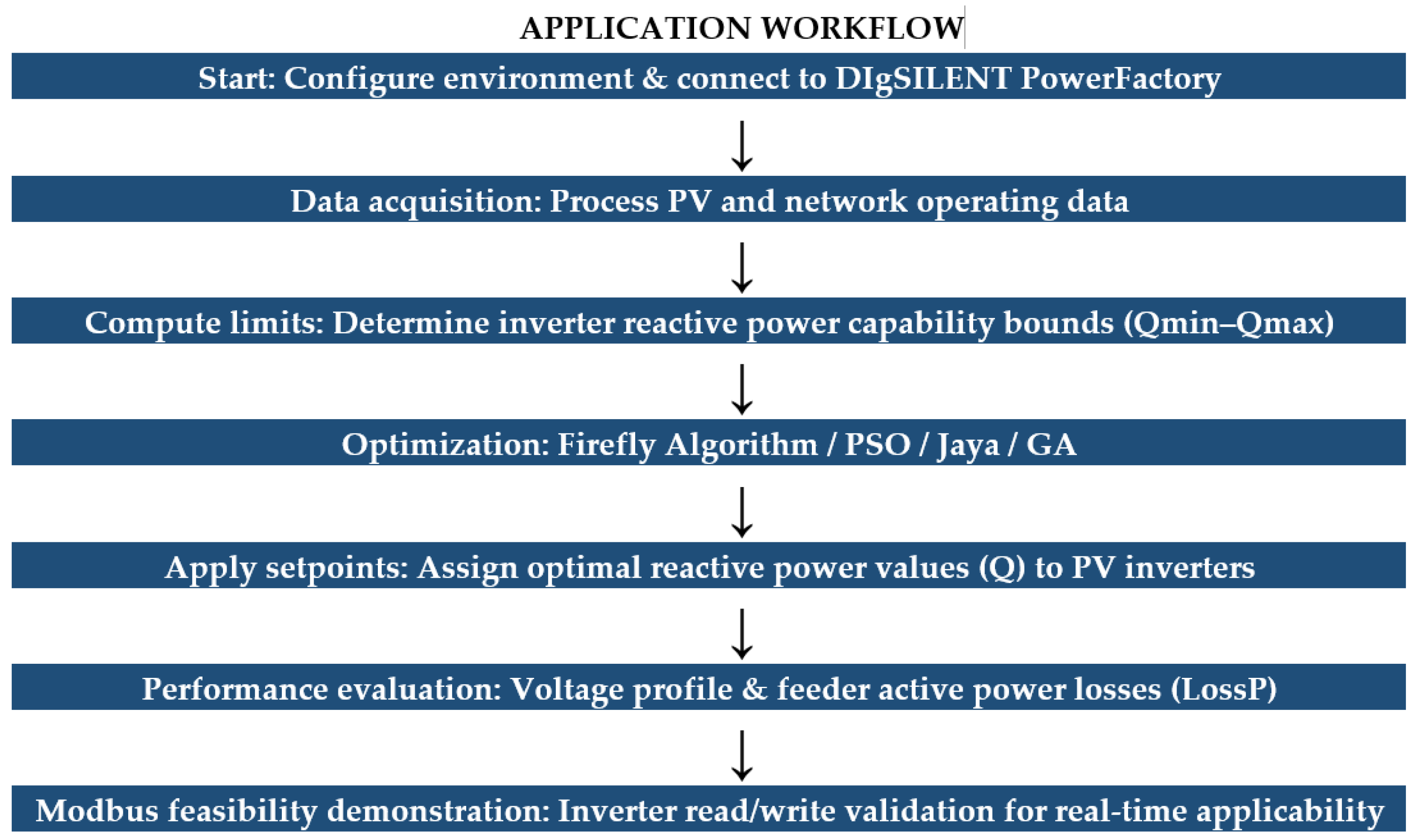

Although DIgSILENT PowerFactory offers multiple tools and capabilities, it can be challenging to apply these tools effectively as network and scenario analyses become more complex. For example, it was not possible to run four different algorithms developed in this study on the data read from the network and apply the results back to the sample network directly through the software. To overcome this issue, the Python API (Python 3.13.9) provided by DIgSILENT PowerFactory is used. The main purpose of the API is to automate tasks that can be time-consuming and error-prone when implemented manually, making them easier and more reliable.

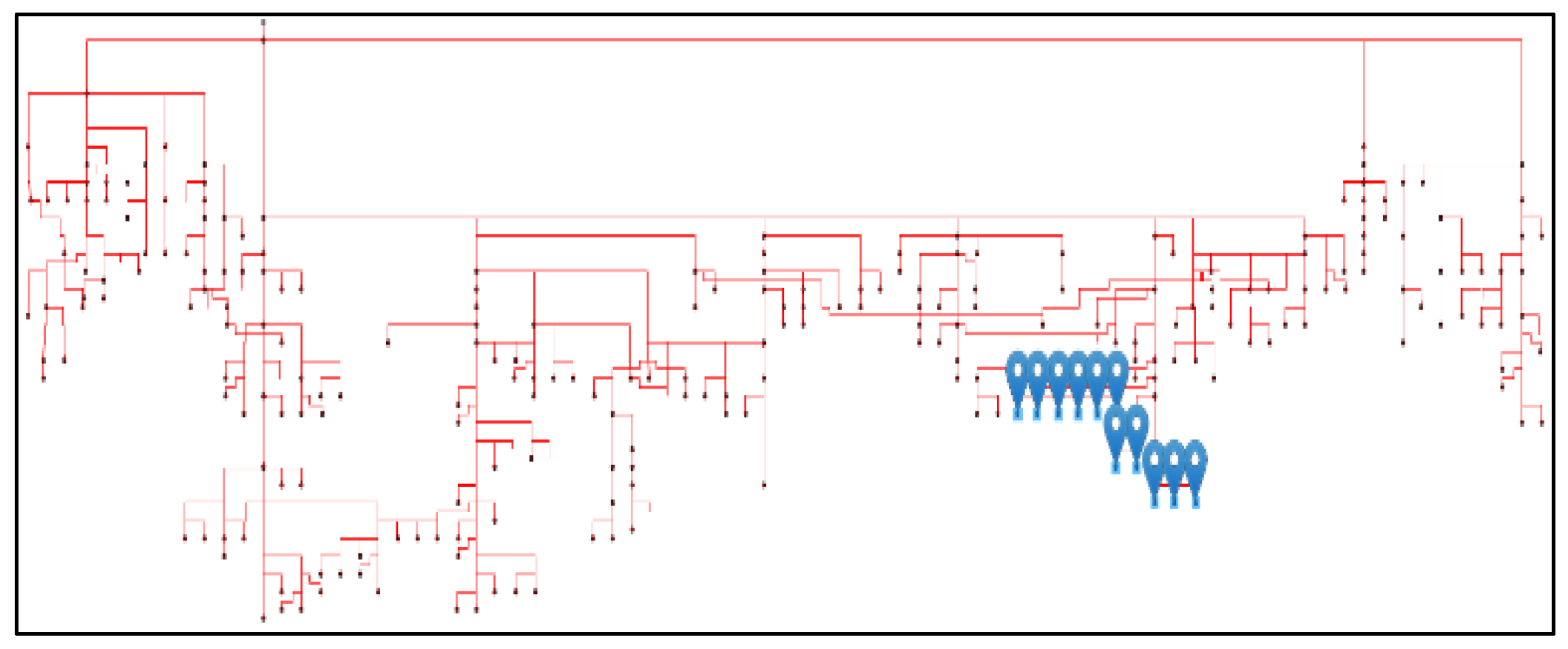

In this study, the analysis is performed on the Adiyaman TM-City 1 feeder of AKEDAS, the distribution system operator of Kahramanmaras and Adiyaman provinces in southern Turkey. There are 12 PV plants in the grid with a total installed capacity of 11.792 MW, and the geographical locations of the PV plants are marked on the DIgSILENT application in

Figure 8. The model was built using real network data integrated with the Geographic Information System (GIS) to reflect actual grid conditions.

As part of the test infrastructure, a Python-based control application was developed to communicate directly with the PV inverters via the Modbus RTU protocol. This Modbus-based activity was conducted solely as a feasibility demonstration to verify inverter accessibility and the capability of remotely writing reactive power reference values. Importantly, the optimization algorithms were not executed in real time in the field; all optimization routines and the quantitative results reported in this manuscript were obtained using the DIgSILENT PowerFactory simulation environment based on the actual feeder model, inverter data, and time-series profiles.

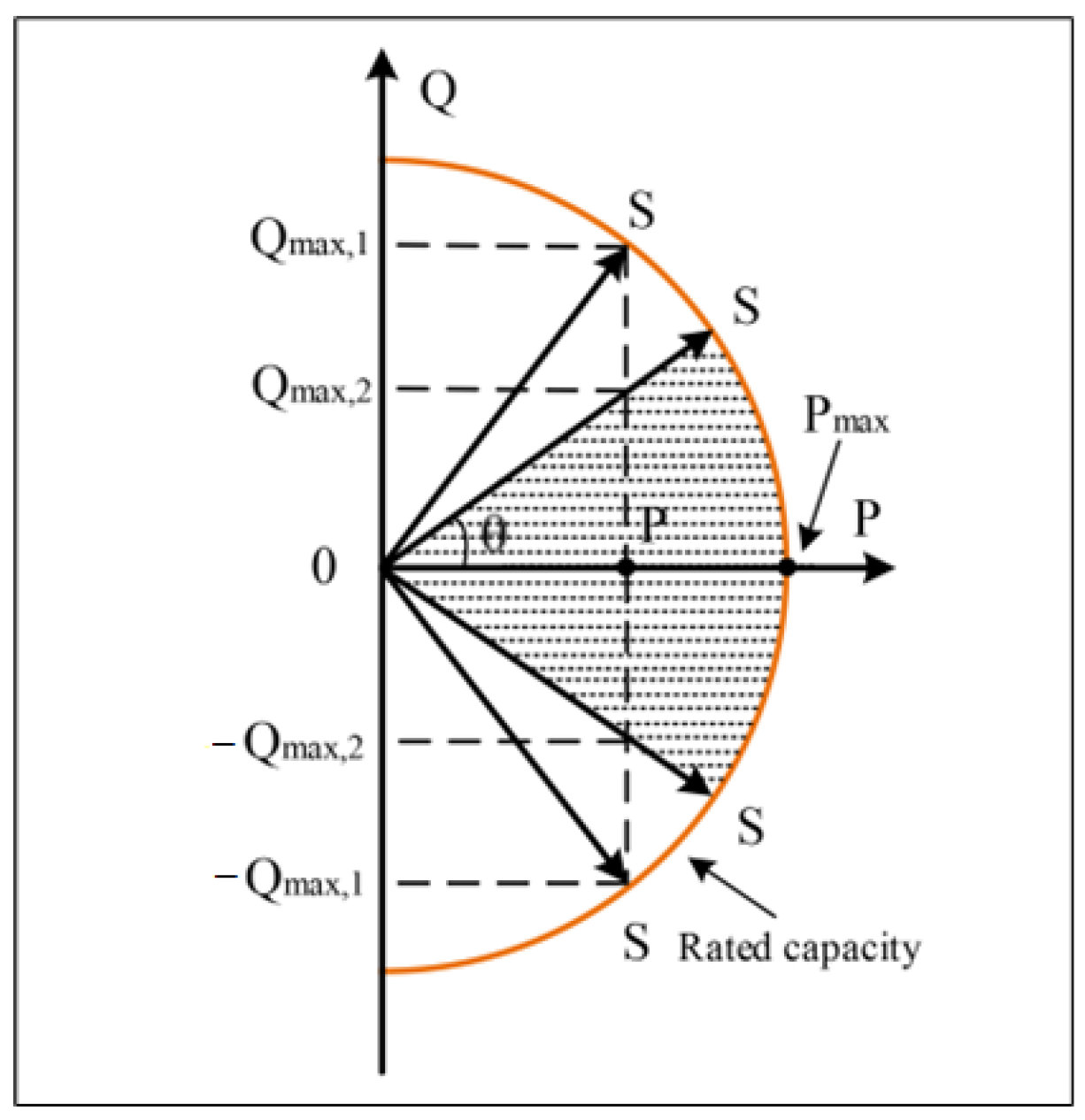

In terms of compliance and protection, the proposed reactive power control respects operational constraints consistent with Turkish distribution grid practice. Specifically, bus voltages are maintained within predefined limits (Vmin ≤ Vi ≤ Vmax), and inverter reactive power references are bounded by inverter capability curves based on rated apparent power (Pk2 + Qk2 ≤ Sk,rated2). The proposed approach does not modify the feeder’s existing protection settings or current protection schemes; it only generates inverter reactive power reference values within allowable operating boundaries. In addition, the Modbus-based feasibility demonstration does not bypass inverter internal protection functions (e.g., over/under-voltage, overcurrent, and anti-islanding) and is only used to verify remote communication and setpoint writing capability.

In addition to voltage profile improvement, the impact of reactive power optimization on feeder active power losses was evaluated using DIgSILENT PowerFactory loss outputs. Reactive power support may redistribute power flows and may increase losses in certain feeder sections due to reactive circulation. Therefore, the main indicator reported in this study is the overall system-level total active power losses (LossP).

Table 3 presents the total LossP values for the baseline case and for each optimized solution at the analyzed operating point (Hour-of-Year 5051–5052).

As shown in

Table 3, the Jaya-based solution achieves the highest reduction in system losses for the analyzed operating point, while the other methods yield losses comparable to the baseline.

It aims to improve the overall voltage profile of the grid with the optimal level of reactive power support from the inverters of each PV power plant connected to the distribution system. Therefore, four different Python-based algorithms are tested on the DIgSILENT PowerFactory application for grid modeling.

The algorithms are designed to optimize the reactive energy generation from the idle capacity of the inverters without limiting the current active power generation of the power plant. During the design, the current, voltage, and defined maximum power limits of the inverters were taken into account, and it was aimed to determine the optimum reactive power values within these limits. Thus, the available capacities of the inverters were effectively utilized, and grid voltage profiles were improved.

Within the scope of the study, each algorithm was run 100 times, and at the end of each run, the deviations of the voltage levels of the busbars in the grid from the ideal value of 1 p.u. were calculated. These deviations were summed, and the average of 100 different results was determined. Finally, the performance of each algorithm was evaluated based on these results.

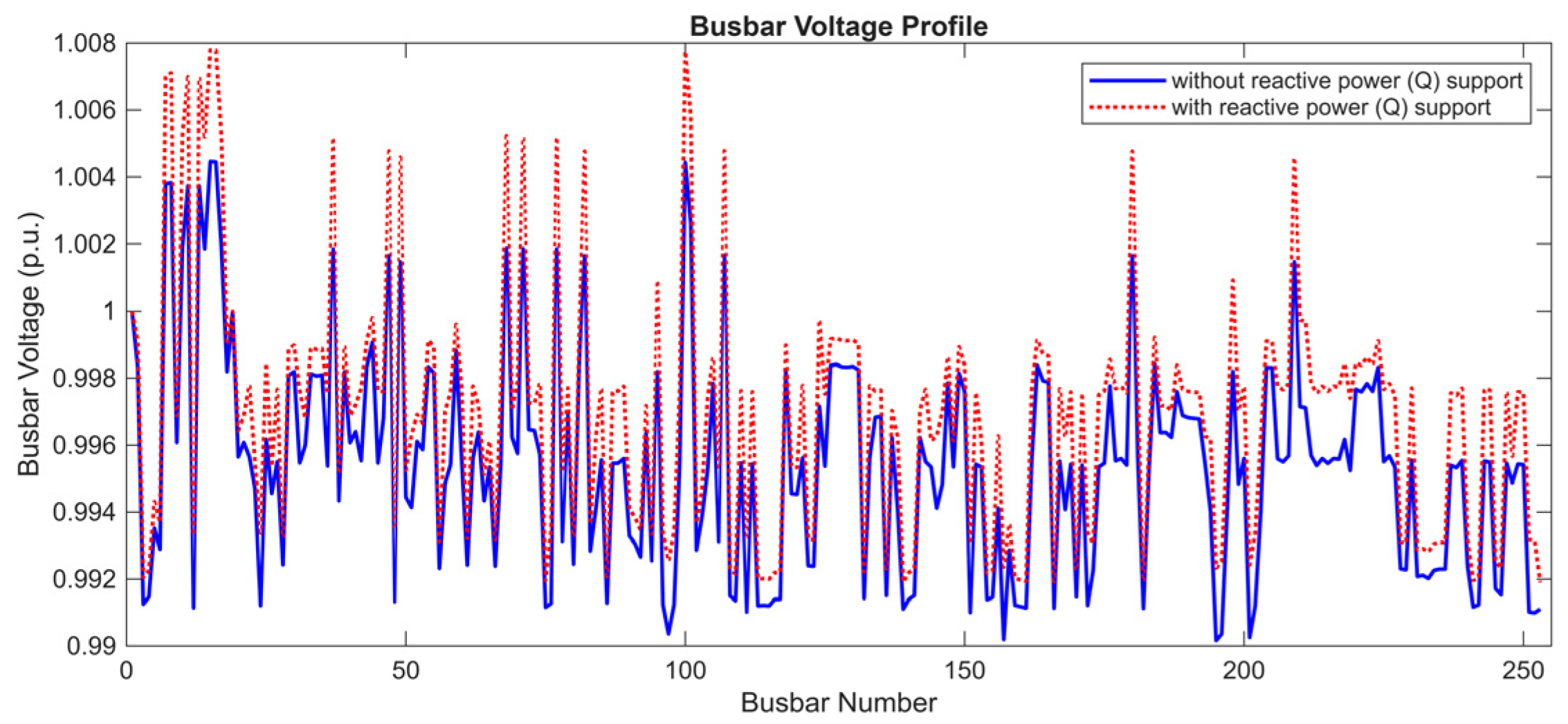

PSO is a population-based meta-heuristic algorithm inspired by collective behavior, such as a flock of birds or a school of fish. The graph of the result obtained with the developed Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm is given in

Figure 9. It shows the changes in the grid voltage profile before and after the application of the PSO Algorithm. The horizontal axis represents the busbars in the grid. The vertical axis represents the deviation of the voltage level of each busbar from the ideal value of 1 p.u.

The blue color represents the voltage deviations before the application of the algorithm, while the red color shows the improved voltage levels after the application of the algorithm and the provision of reactive energy support. The red graph shows that the voltages are closer to the ideal level, indicating that the PSO Algorithm plays an effective role in reducing voltage deviations. The effect of the PSO algorithm on the grid voltage profile is summarized in

Table 4, with the data obtained by running the algorithm for 100 iterations.

These results show that the PSO Algorithm is an effective method for optimizing grid voltage profiles. An average improvement rate of 19.336% demonstrates the overall performance of the algorithm, while the standard deviation value of 0.935% emphasizes the stability and consistency of the results. With its fast convergence and balanced exploration-exploitation structure, the PSO Algorithm proves to be a successful optimization tool for voltage control in distribution networks. Moreover,

Table 5 indicates the amounts of reactive energy supplied and withdrawn from the PV plants.

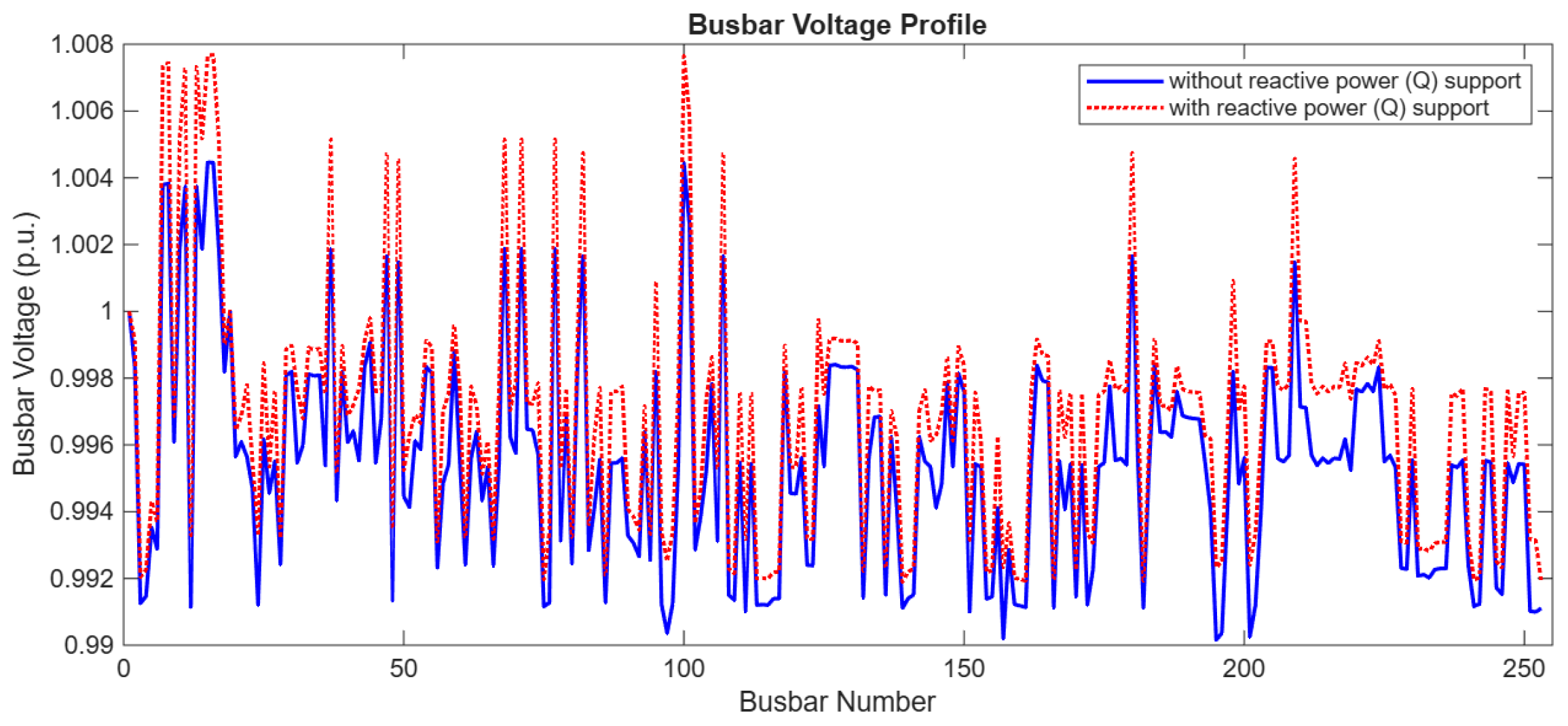

Genetic Algorithm (GA) is a powerful optimization technique inspired by the process of natural selection and evolution.

Figure 10 shows the result obtained using the GA. Here, it shows the changes in the grid voltage profile before and after GA application. The horizontal axis represents the busbars in the grid. The vertical axis shows the deviation of the voltage level of each busbar from the ideal value of 1 p.u.

The blue graph represents the voltage deviations before the application of the algorithm while the red graph represents the improved voltage levels after running the algorithm, which provides reactive energy support. The red graph clearly shows that the voltages are closer to the ideal level (1 p.u.). This shows the effectiveness of GA in reducing voltage deviations. The performance of GA in improving the grid voltage profile is summarized in

Table 6 based on the data obtained by running the algorithm for 100 iterations.

These results show that GA is effective in optimizing grid voltage profiles. An average improvement rate of 19.177% demonstrates the overall performance of the algorithm, while the standard deviation value of 0.961% emphasizes the consistency and stability of the results. This improvement provided by the Genetic Algorithm proves that it is a viable method for voltage control in distribution networks.

Table 7 shows the amounts of reactive energy supplied and withdrawn from PV plants.

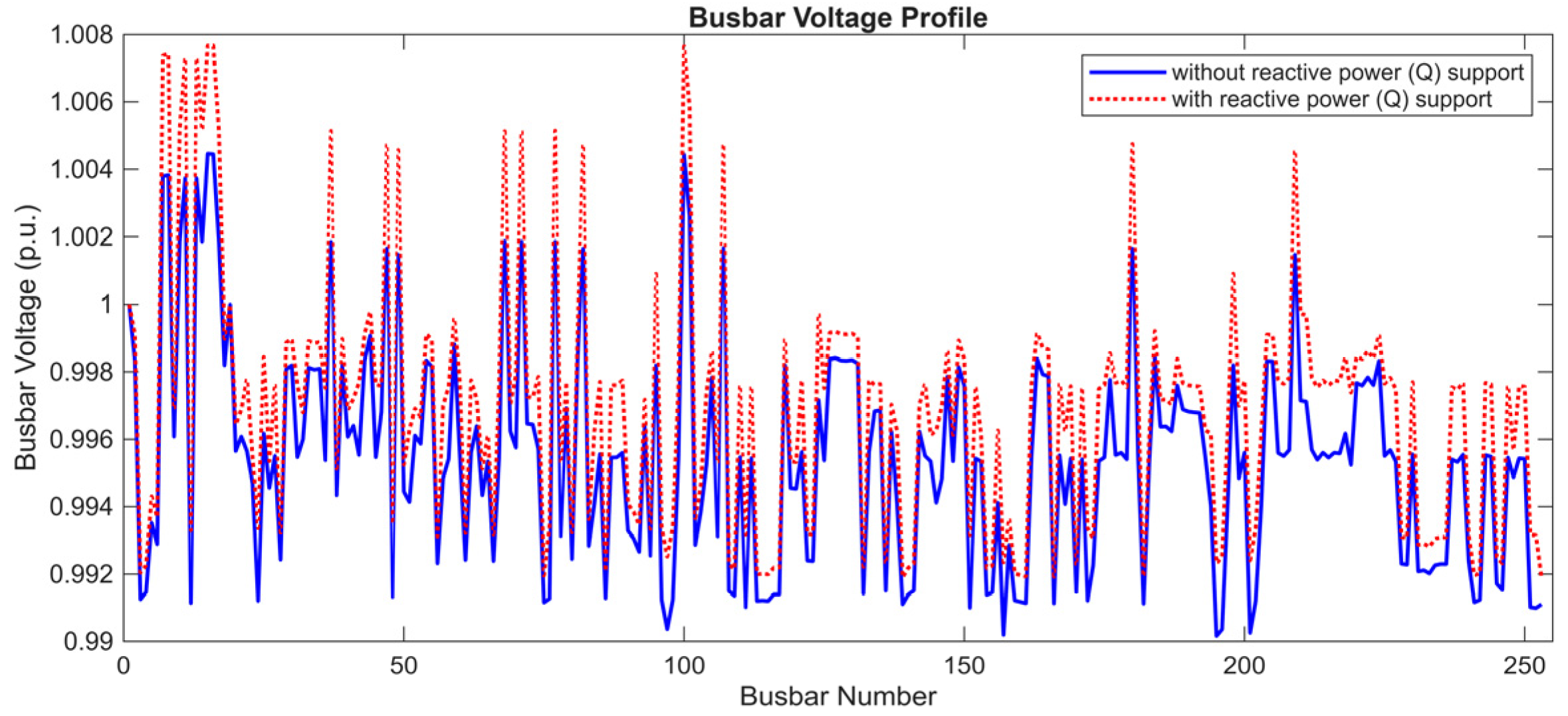

The Jaya algorithm aims to solve optimization problems by improving the quality of a population of potential solutions over iterations. It achieves this by iteratively updating the individuals in the population according to their performance.

Figure 11 shows the results of the algorithm. The figure shows the improvement in the grid voltage profile before and after the implementation of the Jaya algorithm. The horizontal axis represents the busbars in the grid. The vertical axis represents the distance of the voltage level of each busbar from the ideal value of 1 p.u.

The red graph clearly shows that the voltages are closer to the ideal level (1 p.u.), which demonstrates the performance of the Jaya algorithm in reducing voltage deviations. The impact of the Jaya algorithm on the grid voltage profile is summarized in

Table 8 according to the data obtained after running the algorithm for 100 iterations.

These results show that the Jaya algorithm optimizes the grid voltage profiles in an efficient and stable manner. The average improvement rate is about 20%, which indicates the strong performance of the algorithm. Moreover, the low standard deviation value (0.891%) emphasizes the stability and reproducibility of the results obtained. The amounts of reactive energy supplied by and withdrawn from the PV plants are given in

Table 9.

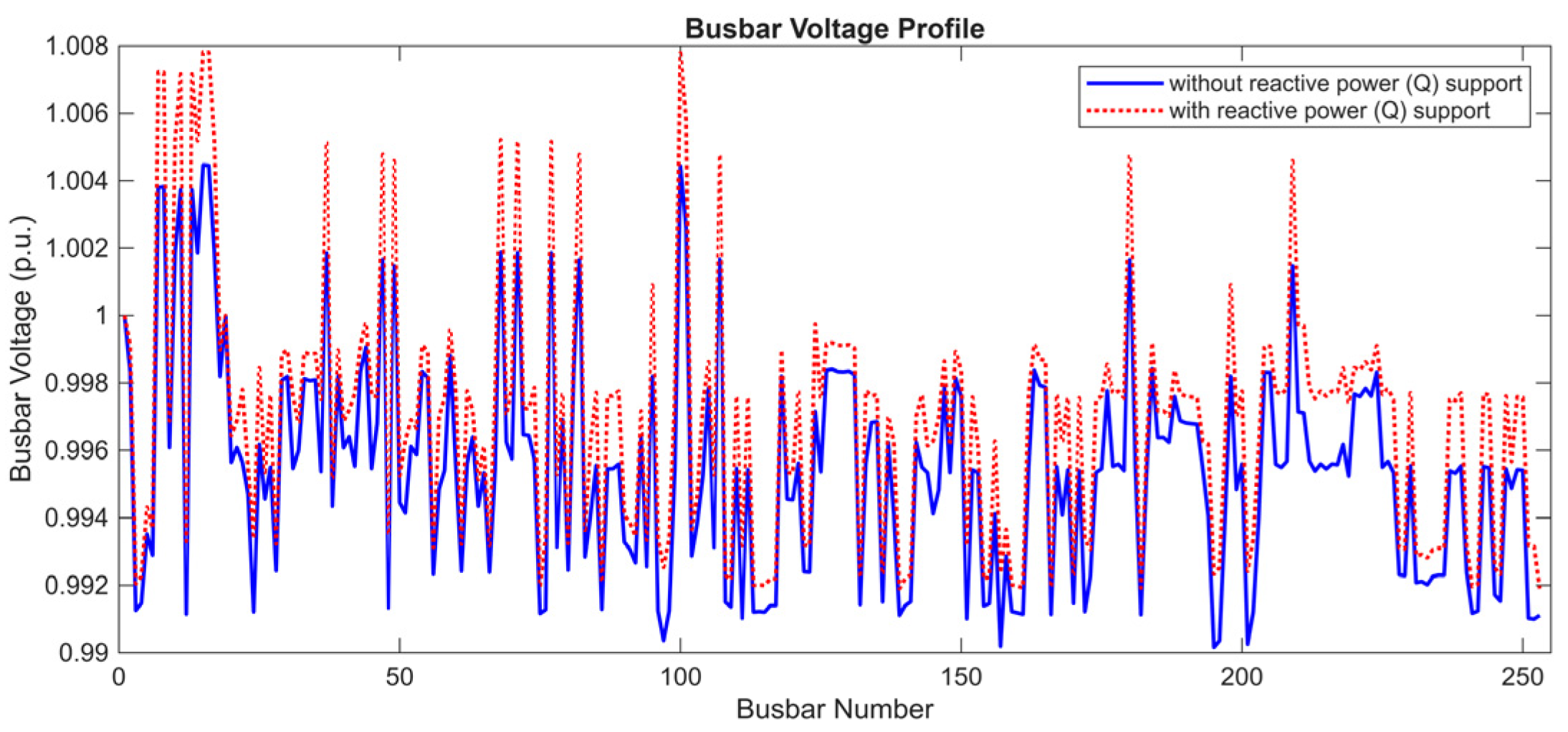

The result of the Firefly Algorithm (FA) is presented in

Figure 12. The figure demonstrates the changes in the grid voltage profile before and after the implementation of the Firefly Algorithm. The horizontal axis represents the busbars in the grid. The vertical axis shows the deviation of the voltage level of each busbar from the ideal value of 1 p.u.

The blue graph represents the voltage deviations before running the algorithm, while the red graph represents the improved voltage levels after the application of the algorithm, which provides reactive energy support. The red graph shows that the voltages are closer to the ideal level, which reveals that the Firefly Algorithm is successful in reducing voltage deviations. The effect of the Firefly Algorithm on the grid voltage profile is summarized in

Table 10 based on the data obtained after running the algorithm for 100 iterations.

These results reveal that the Firefly Algorithm is effective in improving the grid voltage profile. An average improvement rate of 19.250% demonstrates the strong performance of the algorithm, while the low standard deviation value of 0.870% emphasizes the stability and consistency of the obtained results. This capability of the algorithm proves to be an effective tool for optimizing the voltage profile in distribution systems.

Table 11 indicates the amounts of reactive energy supplied by and withdrawn from the PV plants.

In the study, it is observed that Jaya, PSO, GA, and FA are all capable of improving the grid voltage profile by providing optimal reactive power support. After optimization, it is clearly seen that the overall voltage profiles approach the ideal level of 1 p.u. However, there is a limited increase in the voltages on some busbars, mainly due to the relocation of the reactive power source. This causes the voltage to move slightly away from 1 p.u. in the centers connected to or near these PV plants, as the reactive power required by the feeder is taken from PV inverters rather than the substation. As a result, a slight increase in voltage is observed at these substations and feeders.

In the PSO algorithm, fixed learning coefficients (C1 = C2 = 2.0), which are widely recommended in the literature for fast convergence, were employed. The inertia weight was set to W_max = 0.9 and W_min = 0.4 to ensure a balance between exploration and exploitation. Simulations were conducted for a swarm size of 30 particles for 50 iterations. These parameters are based on proven configurations in previous studies and yielded stable and reliable results in our analysis.

For the Genetic Algorithm, the population size was set to 100, with a mating pool of 20 individuals and 80 offspring generated in each generation. The crossover rate was assigned randomly for each cycle, and the mutation rate was kept constant. This structure enabled the algorithm to maintain diversity while effectively steering the population toward the global optimum.

The Jaya algorithm is a parameter-free optimization method that eliminates the need for manual tuning and offers a simple implementation. The algorithm was run for a population size of 25 for 50 iterations. The simulation delivered consistent and effective results.

In the Firefly Algorithm, the attractiveness coefficient (β) was set to 1.0, the light absorption coefficient (γ) to 1.0, and the randomness parameter (α) to 0.5. The algorithm was executed for a population size of 40 for 100 iterations. These values were chosen to ensure both exploration capabilities and convergence performance under varying scenarios.

The parameter values, number of particles, and number of iterations used in the algorithms are given in

Table 12.

Since metaheuristic optimization methods may yield different solutions across independent executions, each algorithm was evaluated over 100 independent runs under identical parameter settings. The mean improvement, best/worst values, and standard deviation are reported in

Table 13 to quantify robustness and uncertainty.

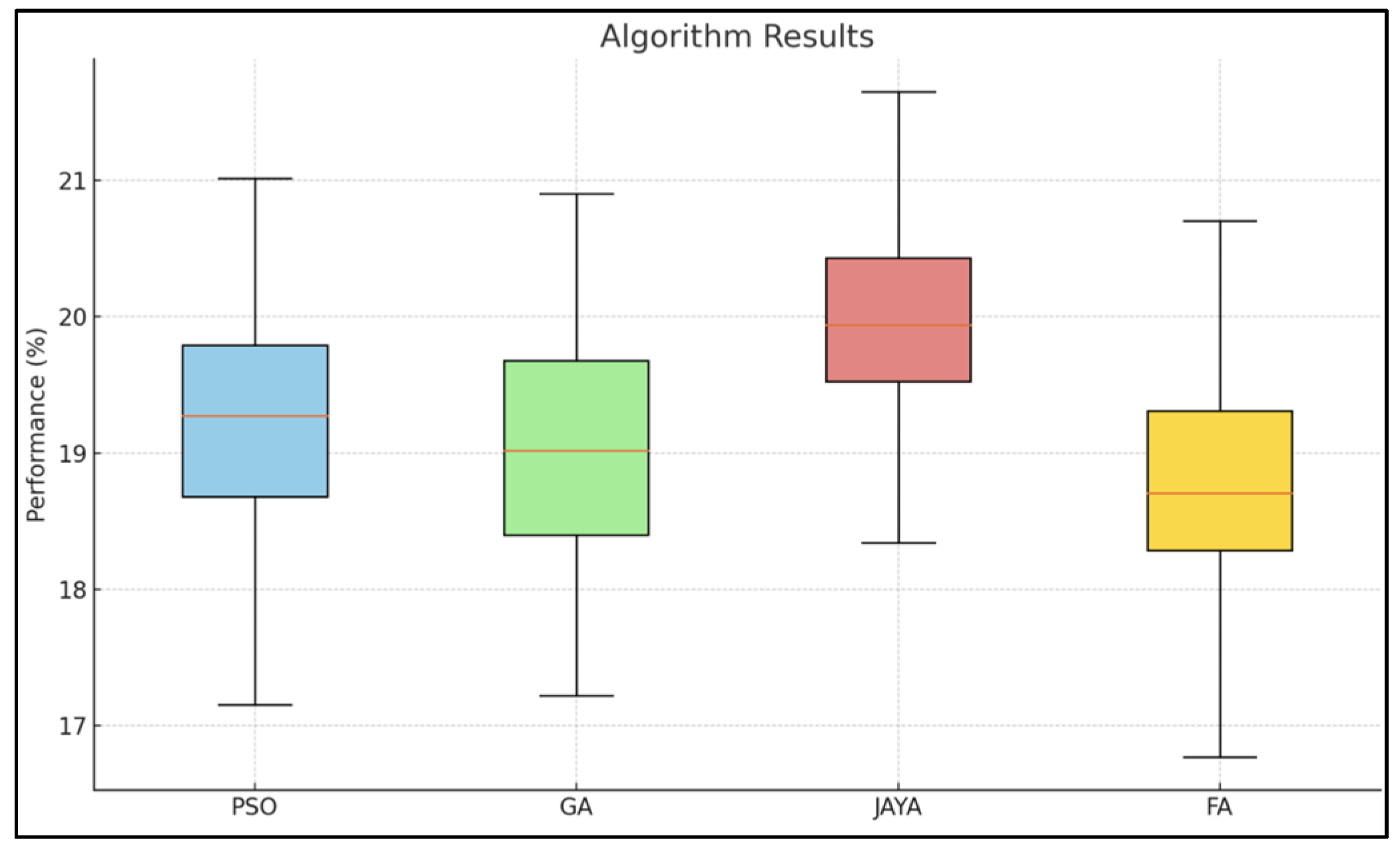

Figure 13 compares the performance of Jaya, PSO, GA, and FA in terms of improvement in the grid voltage profiles. In this figure, the Median is the line in the center of each box, and it represents the median value (midpoint) of the results of that algorithm; the Interquartile Range (IQR) covers the 25th and 75th percentiles of the results. This represents the middle 50% of the distribution of the data. Whisker (extensions) shows the lowest and highest values (with exceptions). X Sign represents the mean value.

It is observed that the Jaya algorithm achieved the best voltage improvement after optimization with 19.919%. The PSO algorithm also showed a similar performance with an improvement of 19.336%, while the FA and GA demonstrated slightly lower improvement rates despite yielding close results (FA = 19.25% and GA = 19.177%). It can be stated that the FA provided more stable and consistent results with the lowest standard deviation value (0.87%).

This evaluation clearly reveals that the Jaya algorithm exhibits superior performance and minimizes voltage deviations more effectively compared to the other algorithms. While the balanced structure of PSO presents a good alternative, the FA and GA contributed to overall stability but with a limited improvement. These results highlight the optimization capabilities of each algorithm from different perspectives.

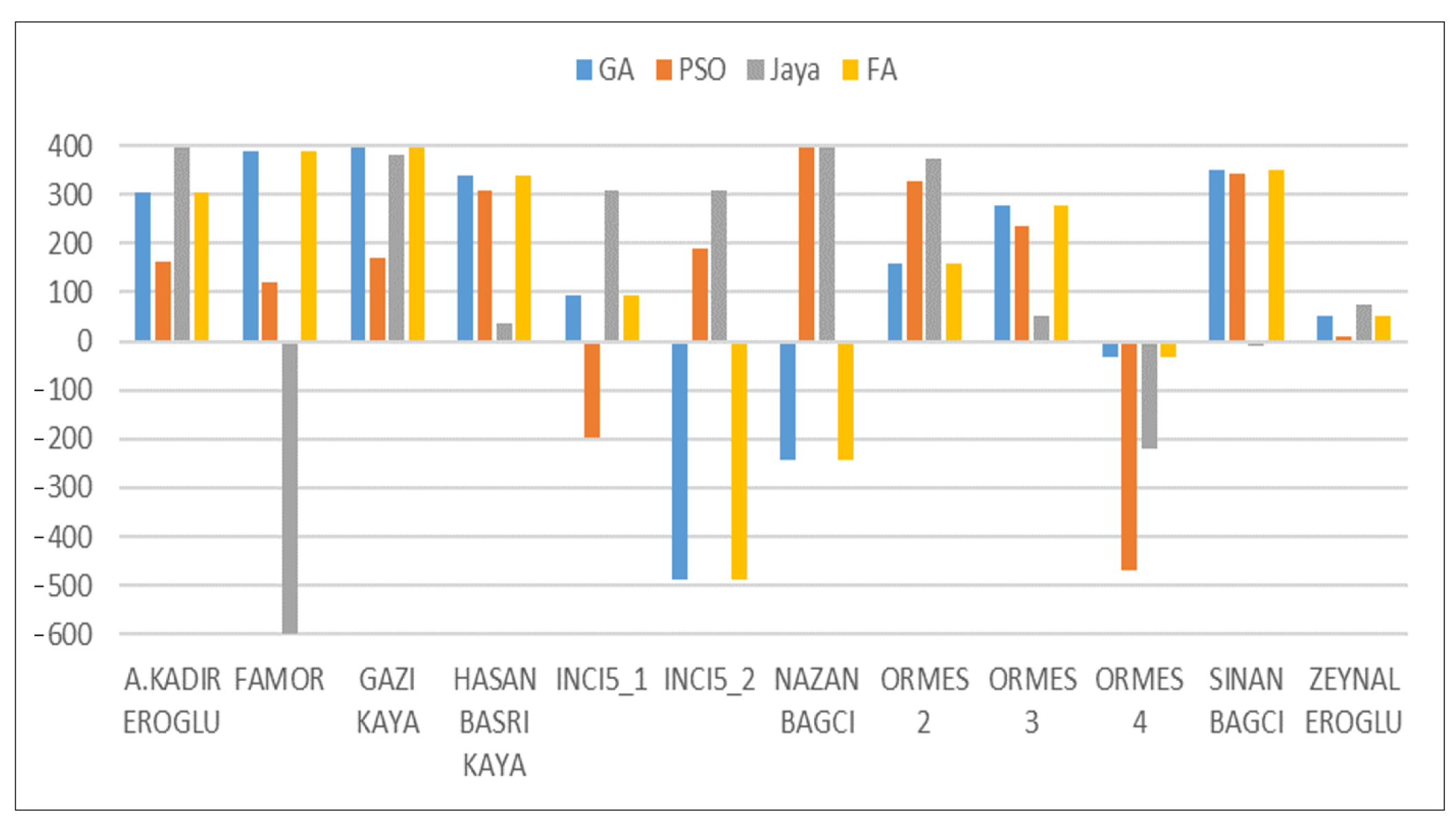

Figure 14 illustrates the reactive power support provided by each algorithm from the PV plants. Positive reactive power values indicate that a voltage drop occurred at the corresponding bus and that the PV plant is attempting to increase the voltage by generating reactive power. Negative reactive power values, on the other hand, indicate that the voltage at the bus is high and that the PV plant is trying to reduce the voltage by absorbing reactive power. Therefore, PV inverters can actively play a role in improving voltage profiles by managing reactive power during their interactions with the grid.