Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal-Free Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

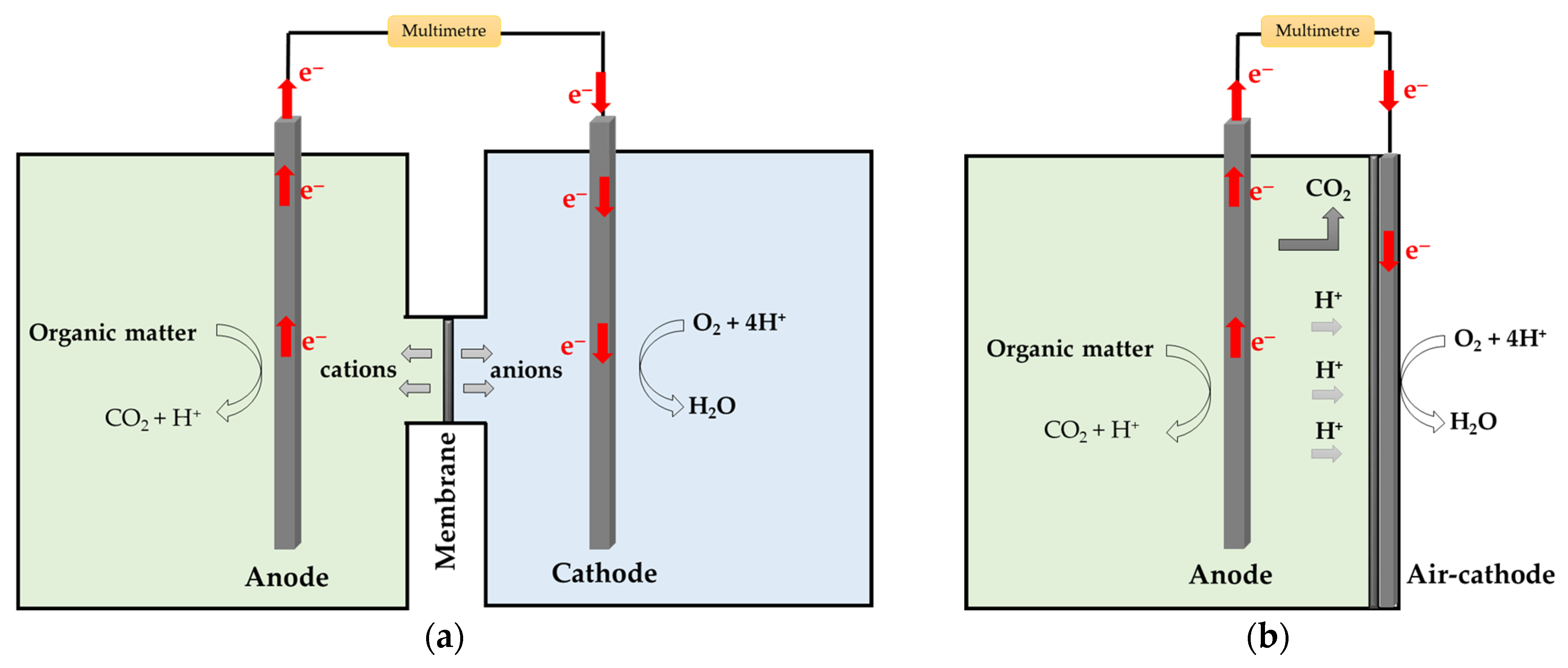

2. MFC Configurations

3. Cathode Materials

3.1. Metal Oxides

3.2. Perovskites

3.3. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Polyoxometalates (POMs)

3.4. Heterojunction Composites

4. ORR Mechanistic Pathways in MFC

5. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MFC | Microbial fuel cells |

| DCMFCs | Dual-chamber MFCs |

| SCMFCs | Single-chamber MFCs |

| ORR | Oxygen reduction reaction |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| CODr | Chemical oxygen demand reduction |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| MOFs | Metal–organic frameworks |

| POMs | Polyoxometalates |

| CN | Nitrogen-modified carbon |

| AC | Activated carbon |

| AAPyr | Aminoantipyrine |

| MPD | Maximum power density |

| OCV | Open circuit voltage |

| RRDE | A rotating ring disk electrode |

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2019 Revision; United Nations: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, A.; Vinestock, T.; Guo, M. Towards Planetary Boundary Sustainability of Food Processing Wastewater, by Resource Recovery & Emission Reduction: A Process System Engineering Perspective. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, C.; Arbizzani, C.; Erable, B.; Ieropoulos, I. Microbial Fuel Cells: From Fundamentals to Applications. A Review. J. Power Sources 2017, 356, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slate, A.J.; Whitehead, K.A.; Brownson, D.A.C.; Banks, C.E. Microbial Fuel Cells: An Overview of Current Technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimnejad, M.; Adhami, A.; Darvari, S.; Zirepour, A.; Oh, S.E. Microbial Fuel Cell as New Technology for Bioelectricity Generation: A Review. Alex. Eng. J. 2015, 54, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Verma, P.; Ray, S. A Comprehensive Review on Bio-Electrochemical Systems for Wastewater Treatment: Process, Electricity Generation and Future Aspect. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, J.V.; Oliveira, V.B.; Simões, M.; Pinto, A.M.F.R. Review on Microbial Fuel Cells Applications, Developments and Costs. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, B.E.; Hamelers, B.; Rozendal, R.; Schröder, U.; Keller, J.; Freguia, S.; Aelterman, P.; Verstraete, W.; Rabaey, K. Microbial Fuel Cells: Methodology and Technology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 5181–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, S.; Huang, L.; Logan, B.E. Scale-up of Membrane-Free Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2008, 179, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, M.; Tian, X.; Tan, C.; Mcdaniel, C.T.; Hassett, D.J.; Gu, T. Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC) Power Performance Improvement through Enhanced Microbial Electrogenicity. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Jain, U.; Chauhan, N. From Waste to Watts-Harnessing the Power of Wastewater to Generate Bioelectricity. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Pazouki, M.; Mohsennia, M. Impact of Modified Electrodes on Boosting Power Density of Microbial Fuel Cell for Effective Domestic Wastewater Treatment: A Case Study of Tehran. Ranliao Huaxue Xuebao J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2017, 45, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erable, B.; Féron, D.; Bergel, A. Microbial Catalysis of the Oxygen Reduction Reaction for Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, H.; Sarapuu, A.; Tammeveski, K. Oxygen Reduction Reaction on Silver Catalysts in Alkaline Media: A Minireview. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.W.; Kalimuthu, P.; Anushya, G.; Chen, S.M.; Ramachandran, R.; Mariyappan, V.; Muthumala, D.C. High-Efficiency of Bi-Functional-Based Perovskite Nanocomposite for Oxygen Evolution and Oxygen Reduction Reaction: An Overview. Materials 2021, 14, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Wang, D.-W. Functional Electrocatalysts Derived from Prussian Blue and Its Analogues for Metal-Air Batteries: Progress and Prospect. Batter. Supercaps 2019, 2, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Sumboja, A.; Wuu, D.; An, T.; Li, B.; Goh, F.W.T.; Hor, T.S.A.; Zong, Y.; Liu, Z. Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Media: From Mechanisms to Recent Advances of Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4643–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seh, Z.W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C.F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K.; Jaramillo, T.F. Combining Theory and Experiment in Electrocatalysis: Insights into Materials Design. Science 2017, 355, eaad499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Kundu, P.P. Recent Advances and Perspectives in Platinum-Free Cathode Catalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustakeem, N. Mustakeem Electrode Materials for Microbial Fuel Cells: Nanomaterial Approach. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2015, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; He, Z. Graphene-Modified Electrodes for Enhancing the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7022–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, T.; Wang, L.; Zhong, J.; Liu, Z. Surface Reorganization on Electrochemically-Induced Zn–Ni–Co Spinel Oxides for Enhanced Oxygen Electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 6554–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Bi, Y.G.; Zhou, S.Q.; Mo, C.H. Transition Metals (Co, Mn, Cu) Based Composites as Catalyst in Microbial Fuel Cells Application: The Effect of Catalyst Composition. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandikes, G.; Peera, S.G.; Singh, L. Perovskite-Based Nanocomposite Electrocatalysts: An Alternative to Platinum ORR Catalyst in Microbial Fuel Cell Cathodes. Energies 2022, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Wei, J.; Mo, R.; Ma, H.; Ai, F. Photocatalytic Microbial Fuel Cells and Performance Applications: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 953434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Logan, B. Continuous Electricity Generation from Domestic Wastewater and Organic Substrates in a Flat Plate Microbial Fuel Cell. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 5809–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, P.; Ala, A.; Nazari, P.; Jalili, B.; Ganji, D.D. A Comprehensive Review of Microbial Fuel Cells Considering Materials, Methods, Structures, and Microorganisms. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luimstra, V.M.; Kennedy, S.J.; Güttler, J.; Wood, S.A.; Williams, D.E.; Packer, M.A. A Cost-Effective Microbial Fuel Cell to Detect and Select for Photosynthetic Electrogenic Activity in Algae and Cyanobacteria. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.K.; Lovley, D.R. Electricity Generation by Direct Oxidation of Glucose in Mediatorless Microbial Fuel Cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1229–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Logan, B.E. Electricity Generation Using an Air-Cathode Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC) in the Absence of a Proton Exchange Membrane. ACS Div. Environ. Chem.-Prepr. Ext. Abstr. 2004, 44, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, B.K.; Mishra, V.; Agrawal, S. Production of Bio-Electricity during Wastewater Treatment Using a Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ramnarayanan, R. Production of Electricity during Wastewater Treatment Using a Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 2281–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Logan, B.E. Increased Performance of Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells Using an Improved Cathode Structure. Electrochem. Commun. 2006, 8, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gu, P.; Liu, J.; Sun, H.; Cai, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zou, J. Navigating the Developments of Air-Cathode Catalysts for Efficient and Sustainable Bio-Energy Production from Wastewater in Microbial Fuel Cells. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 517, 216019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.R.; Jung, S.H.; Regan, J.M.; Logan, B.E. Electricity Generation and Microbial Community Analysis of Alcohol Powered Microbial Fuel Cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2568–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Lee, D.J. Microbial Fuel Cells as Pollutant Treatment Units: Research Updates. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 217, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmuganathan, P.; Rajasulochana, P.; Ramachandra Murthy, A. Factors Affecting the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Khilari, S.; Pradhan, D. Role of Cathode Catalyst in Microbial Fuel Cell. In Microbial Fuel Cell: A Bioelectrochemical System That Converts Waste to Watts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Touach, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Benzaouak, A.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; de Los Rios, A.P.; Labjar, N.; Louki, S.; Mahi, M.E.; Lotfi, E.M. Influence of the Preparation Method of MnO2-Based Cathodes on the Performance of Single-Chamber MFCs Using Wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 171, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Yang, X. Micro-Cu Doped Co3O4 as an Effective Oxygen Reduction Nano-flower-like Catalyst to Enhance the Power Output of Air Cathode Microbial Fuel Cell. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 6080–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, S. α-Fe2O3/Polyaniline Nanocomposites as an Effective Catalyst for Improving the Electrochemical Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 339, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, G.D.; Das, S.; Verma, H.K.; Neethu, B.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Improved Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell by Using Conductive Ink Printed Cathode Containing Co3O4 or Fe3O4. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 310, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, M.; Liu, T.; Liang, P.; Huang, X. Facile Synthesis of Cobalt Oxide as Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 342, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, V.; Rajesh, B.J.; Yogalakshmi, K.N. Synergistic Effect of TiO2 Nanostructured Cathode in Microbial Fuel Cell for Bioelectricity Enhancement. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, G.D.; Noori, T.; Das, I.; Neethu, B.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Mitra, A. Bismuth Doped TiO2 as an Excellent Photocathode Catalyst to Enhance the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 7501–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Yang, B.; Yang, S.; Tong, X.; Wang, M. Cu/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Enhancing Microbial Fuel Cell Performance as Photocathode Catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 430, 132586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. The Potential of Co3O4 Nanoparticles Attached to the Surface of MnO2 Nanorods as Cathode Catalyst for Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Wei, L.; Wang, G.; Shen, J. In-Situ Growing NiCo2O4 Nanoplatelets on Carbon Cloth as Binder-Free Catalyst Air-Cathode for High-Performance Microbial Fuel Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 231, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyaru, S.; Mahalingam, S.; Ahn, Y. A Non-Noble V2O5 Nanorods as an Alternative Cathode Catalyst for Microbial Fuel Cell Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 4974–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garino, N.; Sacco, A.; Castellino, M.; Mun, J.A.; Chiodoni, A.; Agostino, V.; Margaria, V.; Gerosa, M.; Massaglia, G.; Quaglio, M. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide/SnO2 Nanocomposite for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4633–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.; Ho, L.; Guo, K.; Liew, Y.; Aminah, N. Exploring the Potential of Metal Oxides as Cathodic Catalysts in a Double Chambered Microbial Fuel Cell for Phenol Removal and Power Generation. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Pandit, S.; Gupta, A.; Sahni, M.; Rajeev, M.; Fosso-Kankeu, E. Received: Sustainable Mn-doped ZnO Nanoparticles as an Efficient Cathode Catalyst for Enhanced ORR and Photocatalytic Dye Degradation in Microbial Fuel Cells. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-martínez, V.M.; Touati, K.; Salar-garcía, M.J.; Hernández-fernández, F.J. Mixed Transition Metal-Manganese Oxides as Catalysts in MFCs for Bioenergy Generation from Industrial Wastewater. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 151, 107310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.; Mahir, H.; Elhamdouni, Y.; Labjar, N.; El Hamidi, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Kacimi, M.; Liotta, L.F. ZrP2O7 as a Cathodic Material in Single-Chamber MFC for Bioenergy Production. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharti, H.; El, M.; Hitar, H.; Touach, N.; Mostapha, E.; Mohammed, L.; Mahi, E.; Mouhir, L.; Fekhaoui, M.; Benzaouak, A. Generating Sustainable Bioenergy from Wastewater with Ni2V2O7 as a Potential Cathode Catalyst in Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, K.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Huang, Z.; Yan, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Zn-Doped CaFeO3 Perovskite-Derived High Performed Catalyst on Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2021, 489, 229498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Mohsennia, M.; Pazouki, M. Highly Efficient Cathode for the Microbial Fuel Cell Using LaXO3(X = [Co, Mn, Co0.5Mn0.5]) Perovskite Nanoparticles as Electrocatalysts. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, J. Carbon-Supported Perovskite Oxides as Oxygen Reduction Reaction Catalyst in Single Chambered Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, X.; He, H. Preparation and Characteristics of LAXSR1-XCOO3 as Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell. In Particle Science and Engineering, Proceedings of UK–China International Particle Technology Forum IV; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2014; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nandikes, G.; Pathak, P.; Karthikeyan, M. Mesoporous LaFeO3 Perovskite as an Efficient and Cost-Effective Oxygen Reduction Reaction Catalyst in an Air Cathode Microbial Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 52, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Toyir, J.; El Hamdouni, Y.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Labjar, N.; Kacimi, M.; Liotta, L.F. BaTiO3 Functional Perovskite as Photocathode in Microbial Fuel Cells for Energy Production and Wastewater Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; Ríos, A.P.d.L.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Ferroelectric LiTaO3 as Novel Photo-Electrocatalyst in Microbial Fuel Cells Abdellah. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2017, 36, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touach, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.; Salar-García, M.; Benzaouak, A.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; de Ríos, A.P.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E. Particuology On the Use of Ferroelectric Material LiNbO3 as Novel Photocatalyst in Wastewater-Fed Microbial Fuel Cells. Particuology 2017, 34, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.-E.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.; Salar-García, M.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; Ríos, A.d.L.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Ferroelectric Solid Solution Li1−XTa1−XWxO3 as Potential Photocatalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells: Effect of the W Content. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Toyir, J.; El Hamidi, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Kacimi, M.; Liotta, L.F. Bioenergy Generation and Wastewater Purification with Li0.95Ta0.76Nb0.19Mg0.15O3 as New Air-Photocathode for MFCs. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louki, S.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; De Los Ríos, A.P.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Characterization of New Nonstoichiometric Ferroelectric (Li0.95Cu0.15)Ta0.76Nb0.19O3 and Comparative Study With (Li0.95Cu0.15)Ta0.57Nb0.38O3 as Photocatalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2019, 16, 021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, N.-E.; Mazkad, D.; Kharti, H.; Yalcinkaya, F.; Pietrelli, A.; Ferrara, V.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Maximizing Power Generation in Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells: The Role of LiTa0.5Nb0.5O3/g-C3N4 Photocatalyst Nour-Eddine. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2024, 13, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, F.; Kara, K.; Elmazouzi, S.; Lazar, N.; Tajounte, L.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Lotfi, E.M.; Lahmar, A.; Liotta, L.F. Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, T.; Aber, S. Power Generation in a Bio-Photoelectrochemical Cell with NiTiO3 as a Cathodic Photocatalyst. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 895, 115539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Sin, J.; Zeng, H.; Lin, H.; Li, H.; Mohamed, A.R.; Lim, J.W. Ameliorating Cu2+ Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell with Z-Scheme BiFeO3 Decorated on Flower-like ZnO Composite Photocathode. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitar, M.E.H.; Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.-E.; Kharti, H.; Assani, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Sustainable Electricity Generation Using LiTaO3-Modified Mn2+ Ferroelectric Photocathode in Microbial Fuel Cells: Structural Insights and Enhanced Waste Bioconversion. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 837, 141055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Ahmad, A.; Das, S.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Metal Organic Frameworks as Emergent Oxygen-Reducing Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11539–11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Huang, G.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, J. Enhancing Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cell by Cu-Metal Organic Framework@Fe-Metal Organic Framework (Cu-MOF@Fe-MOF) as Cathode Catalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, T.; Ezugwu, C.I.; Wang, Y.; Min, B. Robust Bimetallic Metal-Organic Framework Cathode Catalyst to Boost Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cell. J. Power Sources 2022, 547, 231947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Li, C. Metal-Based Cathode Catalysts for Electrocatalytic ORR in Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yan, R.; Wu, X.; Wan, M.; Yin, B.; Li, S.; Cheng, C.; Thomas, A. Polyoxometalate-Structured Materials: Molecular Fundamentals and Electrocatalytic Roles in Energy Conversions. Adv. Mater. 2004, 36, 2310283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachquer, F.; Oulmekki, A.; Toyir, J. Selective Direct Oxidation of 1-Butanol into Acetal Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Cs5MPW11(H2O)O39 (M=Fe, Co, Cu) Catalysts. Chempluschem 2024, 89, e202300772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachquer, F.; Touach, N.E.; Benzaouak, A.; Oulmekki, A.; Lotfi, E.M.; El Mahi, M.; Toyir, J. Electrocatalytic Performance of Highly Effective Biofuel Cell Using Wastewater Feedstock and Keggin-Type Heteropolyacids-Coated Cathodes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Karami, Z.; Feli, F.; Aber, S. Oxygen Reduction Reaction Enhancement in Microbial Fuel Cell Cathode Using Cesium Phosphomolybdate Electrocatalyst. Fuel 2023, 352, 129040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachquer, F.; Touach, N.-E.; Benzaouak, A.; Oulmekki, A.; Lotfi, E.M.; El Mahi, M.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; Toyir, J. New Application of Polyoxometalate Salts as Cathode Materials in Single Chamber MFC Using Wastewater for Bioenergy Production. Processes 2023, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.; Noori, M.T.; Shaikh, M.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Ananthakrishnan, R. Synthesis and Application of Zirconium Metal−Organic Framework in Microbial Fuel Cells as a Cost-Effective Oxygen Reduction Catalyst with Competitive Performance. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Liu, D.; Li, K.; Yang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. Porous Metal-Organic Framework Cu3(BTC)2 as Catalyst Used in Air-Cathode for High Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q. Simultaneous Sulfamethoxazole Degradation with Electricity Generation by Microbial Fuel Cells Using Ni-MOF-74 as Cathode Catalysts and Quantification of Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Lan, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J. Boosting Oxygen Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cells with Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks-Coated Molybdenum Disulfide as Cathode Catalyst. J. Power Sources 2025, 632, 236386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, M.; Santoro, C.; Serov, A.; Kabir, S.; Artyushkova, K.; Matanovic, I.; Atanassov, P. Air Breathing Cathodes for Microbial Fuel Cell Using Mn-, Fe-, Co- and Ni-Containing Platinum Group Metal-Free Catalysts. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 231, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, K.K.; Kruusenberg, I.; Kibena-Poldsepp, E.; Bhowmick, G.D.; Kook, M.; Tammeveski, K.; Matisen, L.; Merisalu, M.; Sammelselg, V.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; et al. Novel Multi Walled Carbon Nanotube Based Nitrogen Impregnated Co and Fe Cathode Catalysts for Improved Microbial Fuel Cell Performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 23027–23035l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, C.; Shao, C.; Zhuang, S.; Ye, J.; Li, B. Enhancing Oxygen Reduction Reaction by Using Metal-Free Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Black as Cathode Catalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells Treating Wastewater. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingam, S.; Ayyaru, S.; Ahn, Y. Facile One-Pot Microwave Assisted Synthesis of RGO-CuS-ZnS Hybrid Nanocomposite Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Application. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, G.D.; Chakraborty, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Mitra, A. TiO2/Activated Carbon Photo Cathode Catalyst Exposed to Ultraviolet Radiation to Enhance the e Ffi Cacy of Integrated Microbial Fuel Cell-Membrane Bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, S.; Haribabu, K. Bioelectricity Generation in a Microbial Fuel Cell Using Polypyrrole- Molybdenum Oxide Composite as an e Ff Ective Cathode Catalyst. Fuel 2020, 275, 117994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Wang, L.; Waseem, H.; Djellabi, R.; Oladoja, N.A.; Pan, G. FeS@rGO Nanocomposites as Electrocatalysts for Enhanced Chromium Removal and Clean Energy Generation by Microbial Fuel Cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 384, 123335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papiya, F.; Nandy, A.; Mondal, S.; Kundu, P.P. Co/Al2O3-RGO Nanocomposite as Cathode Electrocatalyst for Superior Oxygen Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell Applications: The Effect of Nanocomposite Composition. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 254, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Kundu, P.P. Polyaniline Interweaved Iron Embedded in Urea–Formaldehyde Resin-Based Carbon as a Cost-Effective Catalyst for Power Generation in Microbial Fuel Cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Wei, H.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, T.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, N. ZIF-8-Derived Cu, N Co-Doped Carbon as a Bifunctional Cathode Catalyst for Enhanced Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Guo, R. Fe-N-C-Based Cathode Catalyst Enhances Redox Reaction Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells: Azo Dyes Degradation Accompanied by Electricity Generation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; You, S.; Lin, C.; Cheng, Y. Optimizing Biochar and Conductive Carbon Black Composites as Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cells to Improve Isopropanol Removal and Power Generation. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; En, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Mercado, R.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, S. Cobalt Oxides Nanoparticles Supported on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotubes as High-Efficiency Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cells. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 105, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Kundu, P.P. Magnesium Cobaltite Embedded in Corncob-Derived Nitrogen- Doped Carbon as a Cathode Catalyst for Power Generation in Microbial Fuel Cells. CS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 47633–47649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, N.; Yang, T.; Zhang, T.; Wu, P. Nickel Oxide and Carbon Nanotube Composite (NiO/CNT) as a Novel Cathode Non-Precious Metal Catalyst in Microbial Fuel Cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 72, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Siahrostami, S.; Patel, A.; Nørskov, J.K. Understanding Catalytic Activity Trends in the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2302–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, C.E.; Fabbri, E.; Schmidt, T.J. Perovskite Oxide Based Electrodes for the Oxygen Reduction and Evolution Reactions: The Underlying Mechanism. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 3094–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.N., Jr. Oxygen Reduction Reaction on Smooth Single Crystal Electrodes. In Handbook of Fuel Cells; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gattrell, M.; Macdougall, B. Reaction Mechanisms of the O2 Reduction/Evolution Reaction. In Handbook of Fuel Cells; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.J.; Stamenkovic, V.; Ross, P.N., Jr.; Markovic, N.M. Temperature Dependent Surface Electrochemistry on Pt Single Crystals in Alkaline Electrolyte. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizanac, B.B.; Ross, P.N.; Markovic, N.M. Oxygen Electroreduction on Ag (1 1 1): The PH Effect. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, N.; Mukerjee, S. Alkaline Anion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: Challenges in Electrocatalysis and Interfacial Charge Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 11945–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Yin, G.; Zhang, J. Rotating Ring-Disk Electrode Method; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Catalyst | Matrix | Reactor Type and Scale | Inoculum Source | MPD (mW m−2) | OCV (mV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LaCoO3 | Carbon cloth | DCMFC (350 mL) | Pure culture of Shewanella | 6.99 | 613.84 | [57] |

| LaMnO3 | Carbon cloth | DCMFC (350 mL) | Pure culture of Shewanella | 13.91 | 656.24 | [57] |

| LaCo0.5Mn0.5O3 | Carbon cloth | DCMFC (450 mL) | Pure culture of Shewanella | 8.78 | 634.30 | [57] |

| La0.4Ca0.6Co0.9Fe0.1O3 | Carbon mesh | SCMFC (28 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 405 | 530 | [58] |

| LaFeO3 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (100 mL) | Mature MFC unit | 726.43 | – | [60] |

| Catalyst | Reactor Type and Scale | Inoculum Source | MPD (mW m−2) | OCV (mV) | CODr (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaTiO3 | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 498 | 387 | 90 | [61] |

| Li0.95Ta0.76Nb0.19Mg0.15O3 | SCMFC (250 mL) | Industrial wastewater | 228 | 470 | 95.74 | [65] |

| Li0.95Ta0.57Nb0.38Mg0.15O3 | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 764 | 680 | 75 | [68] |

| Li0.9Mn0.05TaO3 | SCMFC (250 mL) | Industrial wastewater | 370 | 350 | 91 | [71] |

| 3 wt% BiFeO3/ZnO | DCMFC (80 mL) | Sewage wastewater | 1301 | 922 | – | [70] |

| Catalyst | Matrix | Reactor Type and Scale | Inoculum Source | MPD (mW m−2) | OCV (mV) | CODr (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3PMo12O40 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 514 | 638 | 84.66 | [78] |

| H3PW12O40 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 497 | 790 | 73.9 | [78] |

| Cs5PMo11FeO39 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 163.87 | 504 | 83.92 | [80] |

| Cs5PMo11CoO39 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (250 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 119.62 | 470 | 75.9 | [80] |

| Cs3PMo12O40 | Graphite | DCMFC (190 mL) | Activated sludge | 64.73 | 260 | 86.4 | [79] |

| UiO-66 (Zr-MOF) | Carbon felt | SCMFC (150 mL) | MFC anode sludge | 131.2 | 891.1 | 67 | [81] |

| Cu3(BTC)2 | Stainless steel mesh | SCMFC (28 mL) | Domestic wastewater | 1772 | – | – | [82] |

| Ni-MOF-74 | Graphene oxide | SCMFC (28 mL) | Bacterial solution | 446 | 500 | 84 | [83] |

| ZIF-67@MoS2 | Stainless steel mesh | SCMFC (28 mL) | – | 302.5 | 420 | – | [84] |

| Catalyst | Matrix | Reactor Type and Scale | Inoculum Source | MPD (mW m−2) | OCV (mV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoN@C | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (350 mL) | Anodic mixture from dual MF | 1202.3 | 715 | [23] |

| Ppy/MoO2 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (300 mL) | Shewanella putrefaciens | 630 | 671 | [90] |

| FeS@rGO | Graphite felt | DCMFC (140 mL) | MFC anodic effluent | 154 | – | [91] |

| Cu-N/C@Cu-2 | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (28 mL) | Anaerobic sludge | 581 | 703 | [94] |

| Fe-N-C | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (252 mL) | Wastewater sludge | 184 | – | [95] |

| Co/Al2O3-rGO | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (150 mL) | MFC anode consortium | 548.19 | 633 | [92] |

| PANI@Fe/NC | Stainless steel mesh | SCMFC (50 mL) | Activated sludge | 637.53 | 609 | [93] |

| Co/N-CNT | Teflonized carbon cloth | SCMFC (28 mL) | Anaerobic digester sludge | 1260 | – | [97] |

| MgCo2O4/NC-700 | Stainless steel mesh | SCMFC (50 mL) | Activated sludge | 873.81 | 702 | [98] |

| NiO/CNT | Carbon cloth | SCMFC (6.28 mL) | Sludge supernatant | 670 | 772 | [99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lachquer, F.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Toyir, J. Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal-Free Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies. Processes 2026, 14, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030440

Lachquer F, Touach N, Benzaouak A, Toyir J. Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal-Free Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies. Processes. 2026; 14(3):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030440

Chicago/Turabian StyleLachquer, Farah, Noureddine Touach, Abdellah Benzaouak, and Jamil Toyir. 2026. "Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal-Free Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies" Processes 14, no. 3: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030440

APA StyleLachquer, F., Touach, N., Benzaouak, A., & Toyir, J. (2026). Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal-Free Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies. Processes, 14(3), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030440