A Comparative Review of Biomass Conversion to Biodiesel with a Focus on Sunflower Oil: Production Pathways, Sustainability, and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biodiesel Feedstock Classification by Generation

2.1. First Generation

2.1.1. Sunflower Oil

2.1.2. Soybean Oil

2.1.3. Palm Oil

2.2. Second Generation

2.2.1. Jatropha Curcas

2.2.2. Waste Cooking Oil

2.3. Third Generation

2.4. Fourth Generation

2.5. Comparative Summary

2.6. Applications of Biodiesel

2.6.1. Transportation

2.6.2. Power Generation

2.6.3. Heating

2.7. Global Biodiesel Demand

3. Sunflower Oil as a Suitable Biodiesel Feedstock

4. Biodiesel Production Pathways

4.1. Chemical Processes

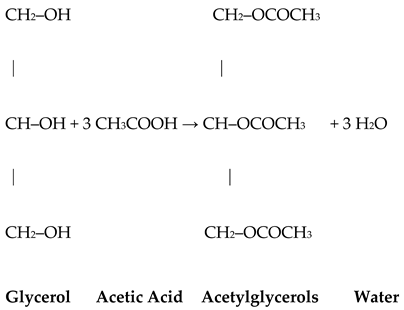

4.1.1. Transesterification Reaction

4.1.2. Supercritical Methanol

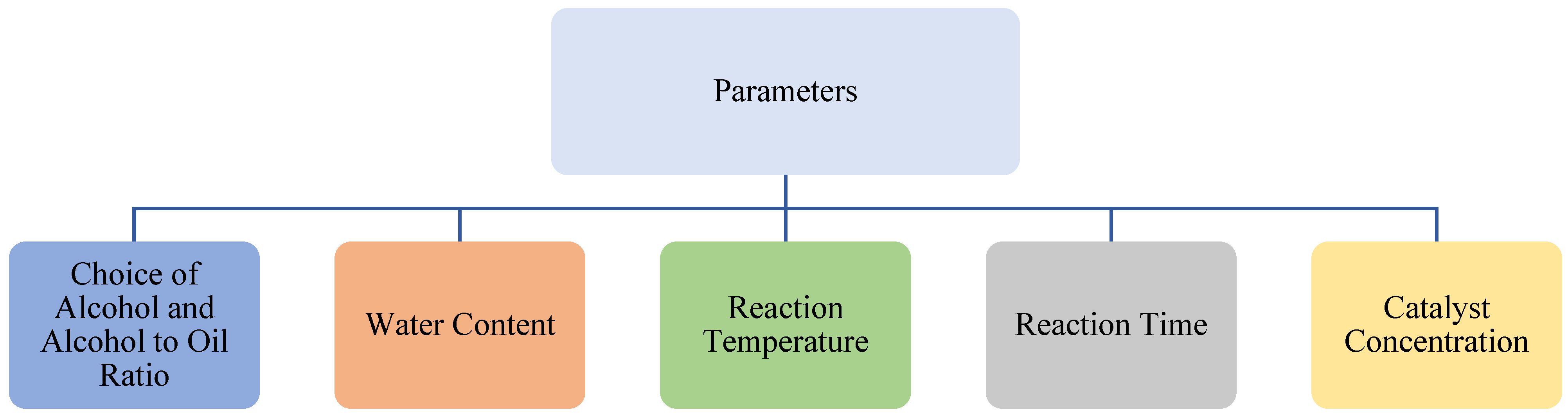

4.2. Parameters Affecting Transesterification Reaction

4.2.1. Choice of Alcohol and Alcohol-to-Oil Ratio

4.2.2. Water Content

4.2.3. Reaction Temperature

4.2.4. Reaction Time

4.2.5. Catalyst Concentration

4.3. Types of Catalysts

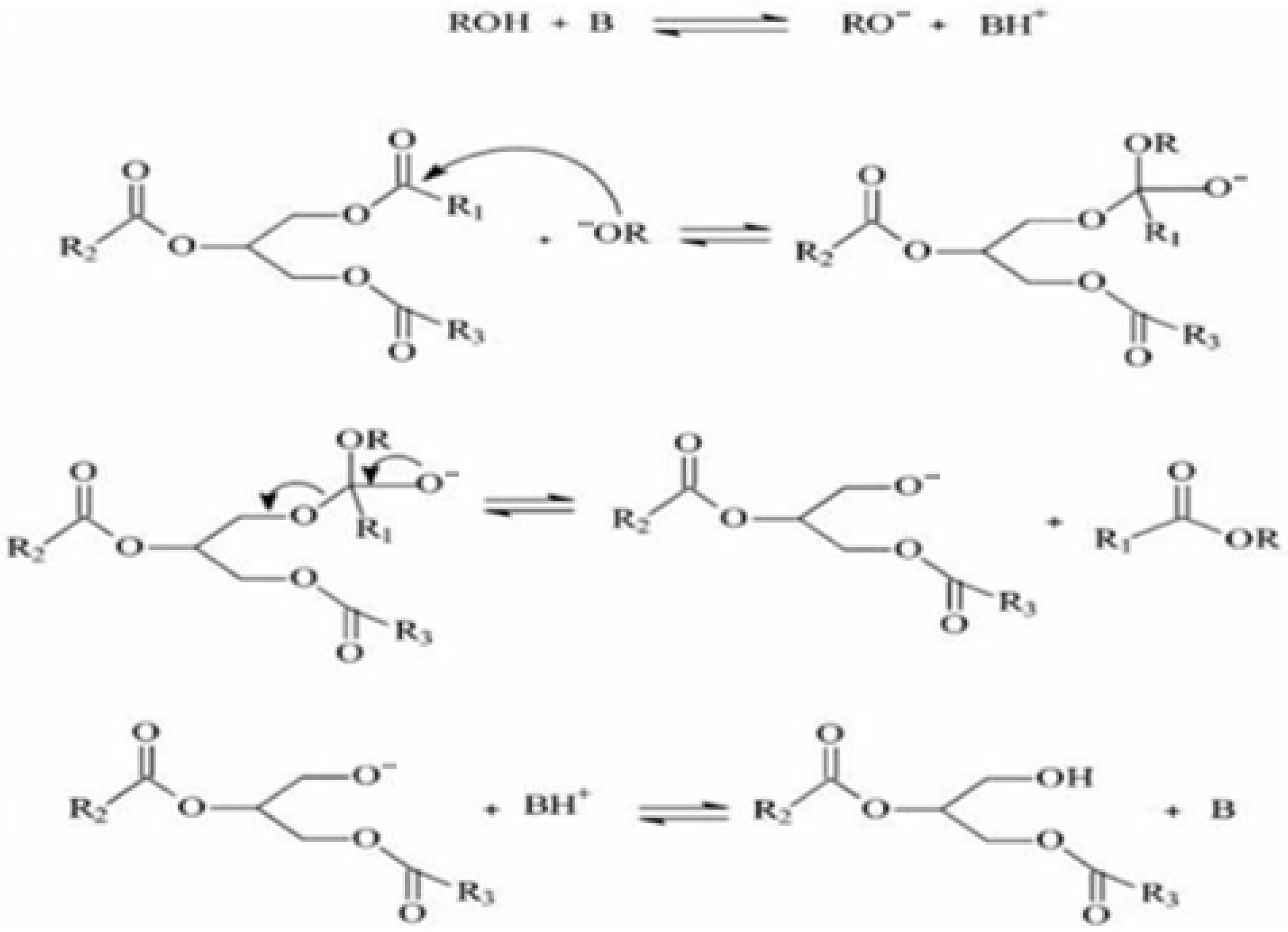

4.3.1. Homogeneous Basic Catalysts

- (1)

- The creation of the active species RO-.

- (2)

- A tetrahedral intermediate is formed due to the nucleophilic attack RO- on a carbonyl group of TG.

- (3)

- The breakdown of the intermediate.

- (4)

- The regeneration of the base.

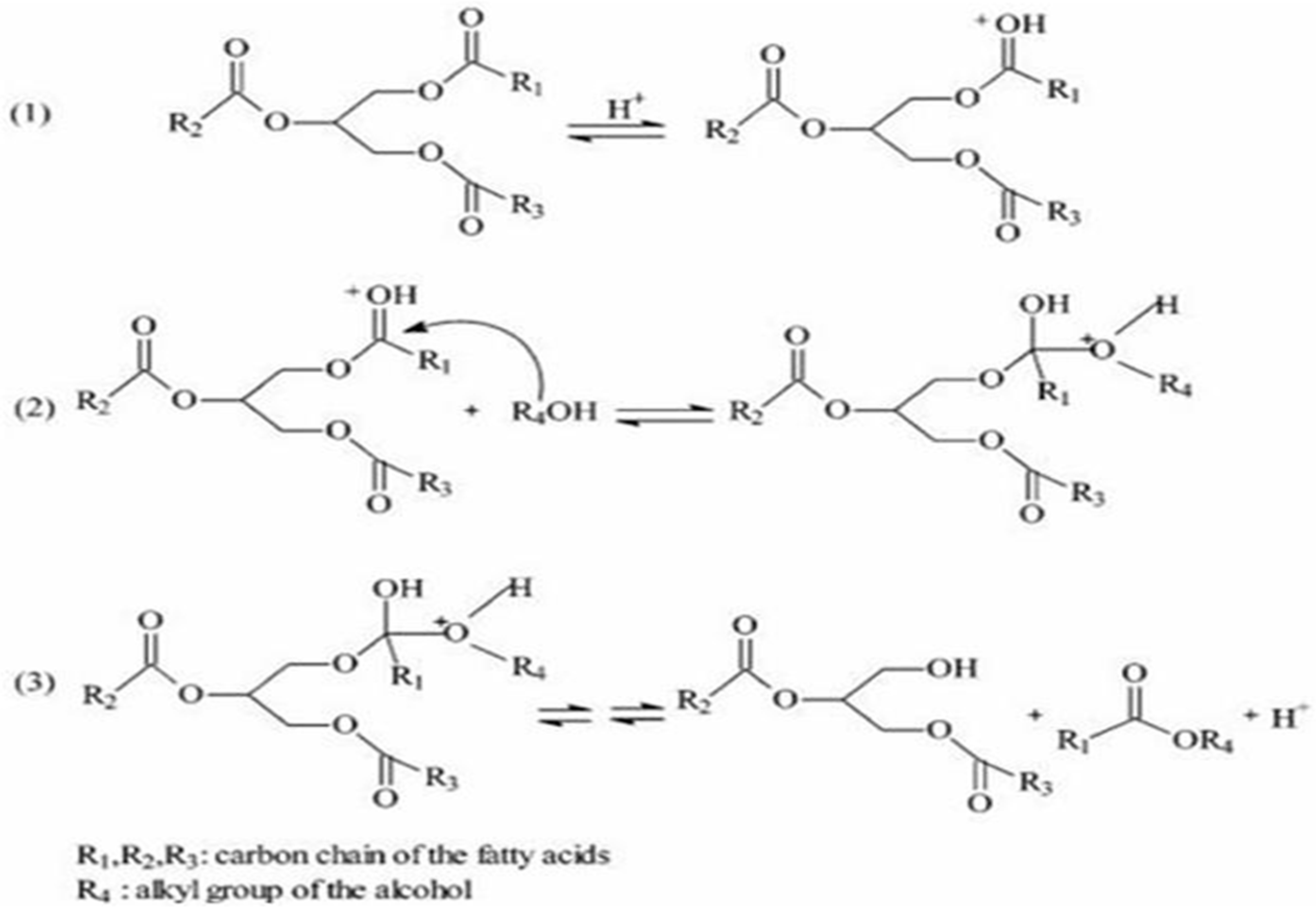

4.3.2. Homogeneous Acidic Catalysts

- (1)

- The acid catalyst protonates the carbonyl group of the triglyceride.

- (2)

- A tetrahedral intermediate is formed by the nucleophilic attack of alcohol.

- (3)

- The intermediate is broken down due to proton migration.

4.3.3. Heterogeneous Catalysts

4.3.4. Enzymatic Catalysts

4.4. Biological Processes

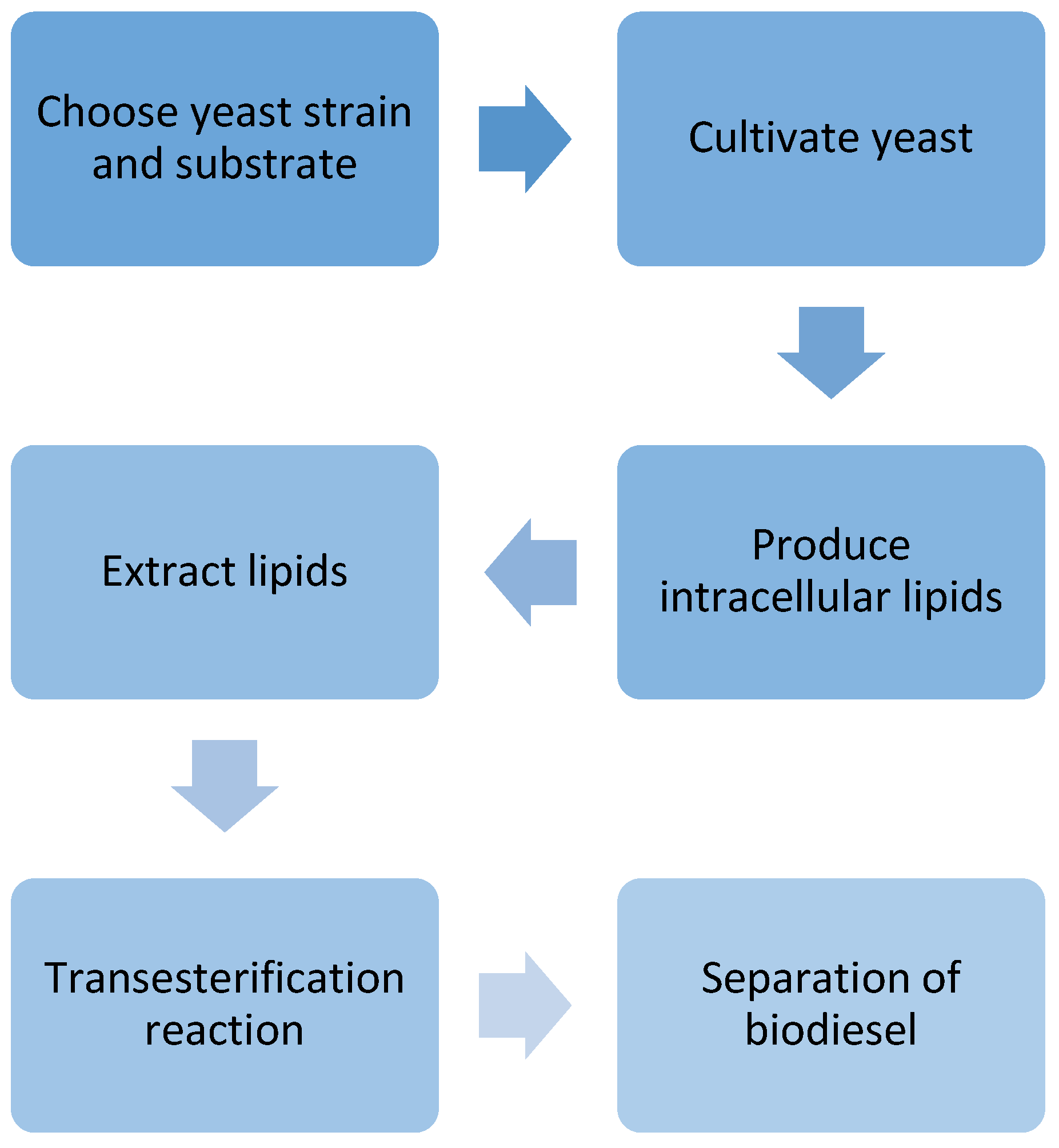

4.4.1. Yeasts

4.4.2. Bacteria

4.5. Comparative Analysis of the Production Pathways

| Production Method | Catalyst Type | Reaction Temp (°C) | Reaction Time (h) | FFA Tolerance | Yield (%) | Separation Ease | Production Cost | Scalability | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Processes | |||||||||

| Alkaline Transesterification | Homogeneous base | 50–65 [1] | 0.5–1.0 [2] | Low (<2%) [53] | 90–98 [11] | Difficult [53] | 0.80–1.10 USD/L [129,130] | High [3] | Soap formation, water-sensitive [53] |

| Acid-Catalyzed Transesterification | Homogeneous acid | 55–80 [1] | 5–10 [2] | High [30] | 80–95 [11] | Difficult [30] | 1.00–1.30 USD/L [30,130] | Medium [30] | Corrosive, slower reaction [30] |

| Emerging Methods | |||||||||

| Heterogeneous Catalysis | Solid catalyst | 60–200 [49] | 2–5 [131] | Medium [49] | 75–95 [11] | Easy [127] | 0.90–1.20 USD/L [96,131] | High [132] | Low waste, recyclable catalysts [127] |

| Supercritical Methanol | No catalyst | 240–400 [82] | <0.5 [82] | High [82] | 90–98 [133] | Easy [133] | 1.30–2.00 USD/L [82,128] | Low–Moderate [133] | High energy input, no waste [128] |

| Enzymatic Transesterification | Lipase enzymes | 30–45 [38] | 8–72 [38] | High [35] | 80–95 [36] | Easy [36] | 1.20–1.80 USD/L [97,101] | Low–Moderate [36] | Biodegradable, green process [134] |

| Biological Processes | |||||||||

| Biological Lipid Production | Yeast/bacteria/algae | 20–37 [134] | Days to weeks [134] | High [134] | 30–70 [134] | Moderate [135] | 2.00–3.50 USD/L [6,134] | Emerging [39] | Circular economy, CO2 use [39] |

4.6. Sustainable Farming Practices

4.7. Land Use and Energy Use

5. Challenges

5.1. Technical Challenges

5.2. Environmental Challenges

5.3. Policy and Regulatory Barriers

5.4. Economic Challenges

6. Sustainability Assessment and SDG Alignment

6.1. Environmental Impact of Conventional Diesel vs. Biodiesel

6.2. Sustainable Feedstock Production and Processing

6.3. Lifecycle Considerations and Resource Efficiency

6.4. Social and Economic Sustainability

6.5. Sustainability Metrics and Certification Frameworks

7. Technological Innovations for Sustainable Biodiesel Production

8. Limitations and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, D.; Sharma, D.; Soni, S.L.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, P.K.; Jhalani, A. A review on feedstocks, production processes, and yield for different generations of biodiesel. Fuel 2020, 262, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, S.N. Biodiesel as a transport fuel, advantages and disadvantages: Review. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2023, 17, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.T.; Hocevar, L.S.; Guarieiro, L.L.N. Biodiesel Technologies: Recent Advances, New Perspectives, and Applications. In Biodiesel Plants—Fueling the Sustainable Outlooks; Zepka, L.Q., Deprá, M.C., Jacob-Lopes, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, J.C.; Mortada, Z.; Rezzoug, S.-A.; Maache-Rezzoug, Z.; Debs, E.; Louka, N. Comparative Review on the Production and Purification of Bioethanol from Biomass: A Focus on Corn. Processes 2024, 12, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentanuhady, J.; Hasan, W.H.; Muflikhun, M.A. Recent Progress on the Implementation of Renewable Biodiesel Fuel for Automotive and Power Plants: Raw Materials Perspective. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5452942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.H.H.; Ong, H.C.; Cheah, M.Y.; Chen, W.-H.; Yu, K.L.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Sustainability of direct biodiesel synthesis from microalgae biomass: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewables 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- THE 17 GOALS. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Kibasa, E.; Vicent, V.; Rweyemamu, L. Valorisation of sunflower press cake with moringa leaves: A novel approach to sustainable food ingredient development. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.K.; Mahajan, A.; Jadhav, S.M.; Kumar, K. Fourth-generation (4G) biodiesel: Paving the way for a greener and sustainable energy future in emerging economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 225, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika; Banga, S.; Pathak, V.V. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review on the application of heterogenous catalysts. Energy Nexus 2023, 10, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiyev, B.; Dukeyeva, A. Influence of Mineral Fertilizers and Methods of Basic Tillage on the Yield and Oil Content of Sunflower. Online J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 23, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, A.S. Community effects associated with sunflower oil production: Systematic review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1379, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, F.; Hikouatcha, P.; Tchoffo, G.; Tédongap, R. Biofuel policies and their ripple effects: An analysis of vegetable oil price dynamics and global consumer responses. Energy Econ. 2023, 128, 107127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santeramo, F.G.; Di Gioia, L.; Lamonaca, E. Price responsiveness of supply and acreage in the EU vegetable oil markets: Policy implications. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Trollman, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Parra-López, C.; Duong, L.; Martindale, W.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Hdaifeh, A.; et al. The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains. Foods 2022, 11, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa, G.V.; Peñaloza, C.A.; Forero, J.D. Combustion and Performance Study of Low-Displacement Compression Ignition Engines Operating with Diesel–Biodiesel Blends. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabaş, H. Determination of Biodiesel Production Volume of Sunflower as the Major Oilseed Crop in Turkey. Black Sea J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 5, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerema, A.; Peeters, A.; Swolfs, S.; Vandevenne, F.; Jacobs, S.; Staes, J.; Meire, P. Soybean Trade: Balancing Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of an Intercontinental Market. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeier, M.; Zhou, L. International Benchmarks for Soybean Production (2022). Available online: https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/resource/2022/03/international-benchmarks-for-soybean-production-2022/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Clemente, T.E.; Cahoon, E.B. Soybean Oil: Genetic Approaches for Modification of Functionality and Total Content. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.K.; Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Malaysian palm oil: Surviving the food versus fuel dispute for a sustainable future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhilef, S.; Siga, S.; Saidur, R. A review on palm oil biodiesel as a source of renewable fuel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentil, J.; Abubakar, S.S.; Obidieh, Y.P.M.; Osei, J.T.; Amuah, E.E.Y.; Fei-Baffoe, B.; Kazapoe, R.W. Sustainable biodiesel production from palm oil mill effluent: Assessing feasibility and environmental impacts. Total. Environ. Eng. 2025, 4, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra-Irujo, G.A.; Aguirrezábal, L.A.N. Sunflower yield and oil quality interactions and variability: Analysis through a simple simulation model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 143, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woittiez, L.S.; Van Wijk, M.T.; Slingerland, M.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Giller, K.E. Yield gaps in oil palm: A quantitative review of contributing factors. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 83, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiya, M.M.K.; Rasul, M.G.; Khan, M.M.K.; Ashwath, N.; Azad, A.K.; Hazrat, M.A. Second Generation Biodiesel: Potential Alternative to-edible Oil-derived Biodiesel. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 1969–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banković-Ilić, I.B.; Stamenković, O.S.; Veljković, V.B. Biodiesel production from non-edible plant oils. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3621–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, J.; Silitonga, A.S.; Tiong, S.K.; Ong, M.Y.; Masudi, A.; Hassan, M.H.; Bin Nur, T.; Nurulita, B.; Sebayang, A.H.; Sebayang, A.R. A Comprehensive exploration of jatropha curcas biodiesel production as a viable alternative feedstock in the fuel industry—Performance evaluation and feasibility analysis. Mech. Eng. Soc. Ind. 2024, 4, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, K.; Dwivedi, A.; Joshipura, M. A review on separation and purification techniques for biodiesel production with special emphasis on Jatropha oil as a feedstock. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 14, e2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N.H.C.; Khairuddin, N.; Siddique, B.M.; Hassan, M.A. Potential of Jatropha curcas L. as Biodiesel Feedstock in Malaysia: A Concise Review. Processes 2020, 8, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, B.-L.; Zhao, X.; Sagisaka, M.; Shibazaki, R. System Approach for Evaluating the Potential Yield and Plantation of Jatropha curcas L. on a Global Scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2204–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpo, S.O.; Edafiadhe, E.D. Unlocking the Power of Waste Cooking Oils for Sustainable Energy Production and Circular Economy: A Review. Abuad J. Eng. Res. Dev. (AJERD) 2024, 7, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Mudin, A.; Jaat, M.; Mustaffa, N.; Manshoor, B.; Fawzi, M.; Razali, M.A.; Ngali, M.Z. Effects of Biodiesel Derived by Waste Cooking Oil on Fuel Consumption and Performance of Diesel Engine. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 554, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, S.; Amin, M.H.M. Fish Bone-Catalyzed Methanolysis of Waste Cooking Oil. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2016, 11, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Miranda, S.M.; Belo, I. Microbial valorization of waste cooking oils for valuable compounds production—A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 2583–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, M. 3rd-Generation Biofuels: Bacteria and Algae as Sustainable Producers and Converters. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation; Chen, W.-Y., Suzuki, T., Lackner, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3173–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, N.; Rao, P.K.; Sarkar, A.; Kubavat, J.; Vadivel, S.; Manwar, N.R.; Paul, B. Advancements in sustainable biodiesel production: A comprehensive review of bio-waste derived catalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 318, 118884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, M.F. Biofuels from Algae for Sustainable Development. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Biofuels in Transport Sector, in Low Carbon Energy Supply. In Green Energy and Technology; Sharma, A., Shukla, A., Aye, L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.M.; Tayeb, A.M.; Abdel-Hamid, S.M.S.; Osman, R.M. Recent advances in transesterification for sustainable biodiesel production, challenges, and prospects: A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 12722–12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Visconte, G.S.; Spicer, A.; Chuck, C.J.; Allen, M.J. The Microalgae Biorefinery: A Perspective on the Current Status and Future Opportunities Using Genetic Modification. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, K.; Belcher, M.S.; Shih, P.M. Defining and engineering bioenergy plant feedstock ideotypes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, B.; Muhammad, S.A.F.S.; Shokravi, Z.; Ismail, S.; Kassim, K.A.; Mahmood, A.N.; Aziz, M.A. Fourth generation biofuel: A review on risks and mitigation strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.H.; Zaine, S.N.A.; Ho, Y.C.; Uemura, Y.; Lam, M.K.; Khoo, K.S.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Cheng, C.K.; Show, P.L.; Lim, J.W. Impact of various microalgal-bacterial populations on municipal wastewater bioremediation and its energy feasibility for lipid-based biofuel production. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 249, 109384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Chen, G.; Cao, X.; Wei, D. Molecular characterization of CO2 sequestration and assimilation in microalgae and its biotechnological applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, N.S.M.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Show, P.L.; Chen, W.; Nguyen, T.H.P. Sustainability of the four generations of biofuels —A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 9266–9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraatkar, A.K.; Ahmadzadeh, H.; Talebi, A.F.; Moheimani, N.R.; McHenry, M.P. Potential use of algae for heavy metal bioremediation, a critical review. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Sabouni, R.; Ahmadipour, M. From waste to fuel: Challenging aspects in sustainable biodiesel production from lignocellulosic biomass feedstocks and role of metal organic framework as innovative heterogeneous catalysts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 206, 117554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigerian Jatropha Curcas Oil Seeds: Prospect for Biodiesel Production in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236160581_Nigerian_Jatropha_Curcas_Oil_Seeds_Prospect_for_Biodiesel_Production_in_Nigeria (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Artificial Seawater Biodesalination and Biodiesel Production Using Some Microalgal Species. Available online: https://ejabf.journals.ekb.eg/article_315215_5c48489e4d6acd00b1d0dc0fcb94e383.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Moriarty, K.; Lewis, J.; Milbrandt, A.; Schwab, A. 2017 Bioenergy Industry Status Report, 2020. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/75776.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Demirbas, A. Importance of biodiesel as transportation fuel. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 4661–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chowdhury, A. An exploration of biodiesel for application in aviation and automobile sector. Energy Nexus 2023, 10, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Da Silva, E.S.; Andersen, S.L.F.; Abrahão, R. Life cycle assessment of the transesterification double step process for biodiesel production from refined soybean oil in Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 11025–11033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werncke, I.; Souza, S.N.M.D.; Bassegio, D.; Secco, D. Comparison of emissions and engine performance of crambe biodiesel and biogas. Eng. Agric. 2023, 43, e20220104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietiedt, G.H.; Schlosser, J.F.; Ribas, R.L.; Frantz, U.G.; Russini, A. Desempenho de motor de injeção direta sob misturas de biodiesel metílico de soja. Cienc. Rural. 2011, 41, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofijur, M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Atabani, A.E.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Mobarak, H.M. Comparative evaluation of performance and emission characteristics of Moringa oleifera and Palm oil based biodiesel in a diesel engine. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 53, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metal, K. Biodiesel: Applications. Kumar Metal Industries. Available online: https://kumarmetal.com/biodiesel-applications-replace-petroleum-based-diesel/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Ebrahimian, E.; Denayer, J.F.M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Karimi, K. Biomethane and biodiesel production from sunflower crop: A biorefinery perspective. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, G.M.; Raina, D.; Narisetty, V.; Kumar, V.; Saran, S.; Pugazhendi, A.; Sindhu, R.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Recent advances in biodiesel production: Challenges and solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunkunle, O.; Ahmed, N.A. A review of global current scenario of biodiesel adoption and combustion in vehicular diesel engines. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 1560–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, I.O.; Edeh, I.; Uyigue, L. A Review on Biodiesel Production. Pet. Chem. Ind. Int. 2023, 6, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biodiesel Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report, 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/biodiesel-market# (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Naylor, R.L.; Higgins, M.M. The rise in global biodiesel production: Implications for food security. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirma, V.; Neverauskienė, L.O.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Danilevičienė, I.; Tamošiūnienė, R. The Impact of Renewable Energy Development on Economic Growth. Energies 2024, 17, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Hoz, J.; Martín, H.; Ballart, J.; Córcoles, F.; Graells, M. Evaluating the new control structure for the promotion of grid connected photovoltaic systems in Spain: Performance analysis of the period 2008–2010. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 19, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. Dependence of biodiesel fuel properties on the structure of fatty acid alkyl esters. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuerta, M.; Armas, O.; Rodriguezfernandez, J. Effect of biodiesel fuels on diesel engine emissions. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, S.K.; Broch, A.; Robbins, C.; Ceniceros, E.; Natarajan, M. Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilorgé, E. Sunflower in the global vegetable oil system: Situation, specificities and perspectives. OCL 2020, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Meunier, F.C. Esterification of free fatty acids in sunflower oil over solid acid catalysts using batch and fixed bed-reactors. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 333, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunyanart, P.; Simasatitkul, L.; Juyploy, P.; Kotluklan, P.; Chanbumrung, J.; Seeyangnok, S. The prediction of biodiesel production yield from transesterification of vegetable oils with machine learning. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurre, S.K.; Yadav, J. A review on bio-based feedstock, synthesis, and chemical modification to enhance tribological properties of biolubricants. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 193, 116122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunflower Seed Production, 1961 to 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/sunflower-seed-production?tab=line&time=earliest..2023#sources-and-processing (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Elgharbawy, A.S.; Sadik, W.A.; Sadek, O.M.; Kasaby, M.A. A Review on Biodiesel Feedstocks and Production Technologies. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2021, 66, 5098–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanakaewsomboon, I.; Moollakorn, A. Soap formation in biodiesel production: Effect of water content on saponification reaction. Int. J. Chem. Environ. Sci. 2021, 2, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-W. Engine Performance of High-Acid Oil-Biodiesel through Supercritical Transesterification. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.T. Supercritical and Superheated Technologies: Future of Biodiesel Production. J. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2015, 5, e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-Y.; Huang, T.-C.; Chen, H.-H. Biodiesel Production Using Supercritical Methanol with Carbon Dioxide and Acetic Acid. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 789594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; Gadalla, M.; Saha, B. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil via supercritical methanol: Optimisation and reactor simulation. Renew. Energy 2018, 124, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, S.; Kusdiana, D. Biodiesel fuel from rapeseed oil as prepared in supercritical methanol. Fuel 2001, 80, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusdiana, D.; Saka, S. Effects of water on biodiesel fuel production by supercritical methanol treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 91, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadbeigi, A.; Mahmoudi, M.; Fereidooni, L.; Akbari, M.; Kasaeian, A. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: A review on production methods, recycling models, materials and catalysts. J. Therm. Eng. 2024, 10, 1362–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chozhavendhan, S.; Singh, M.V.P.; Fransila, B.; Kumar, R.P.; Devi, G.K. A review on influencing parameters of biodiesel production and purification processes. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 1–2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.A. The effects of alcohol to oil molar ratios and the type of alcohol on biodiesel production using transesterification process. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Sharma, M.P. Review of process parameters for biodiesel production from different feedstocks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, M.; Ganapathi, A. Factors Affecting Biodiesel Production. Res. Plant Biol. 2011, 1, 1–5. Available online: https://updatepublishing.com/journal/index.php/ripb/article/view/2566 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Verma, P.; Sharma, M.P.; Dwivedi, G. Impact of alcohol on biodiesel production and properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Aziz, A.R.A.; Sulaiman, N.M.N. The effects of water on biodiesel production and refining technologies: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3456–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istiningrum, R.B.; Aprianto, T.; Pamungkas, F.L.U. Effect of reaction temperature on biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using lipase as biocatalyst. In Proceedings of the International Conference and Workshop on Mathematical Analysis and Its Applications (ICWOMAA 2017), Malang, Indonesia, 2–3 August 2017; p. 020031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodua, S.T.; Boadi, N.O.; Badu, M. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions in Biodiesel Production: The Case of Baobab Seed Oil as Alternative Feedstock. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 1498240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmana, A.D.; Tambun, R.; Haryanto, B.; Alexander, V. Effect of Reaction Time on Biodiesel Production from Palm Fatty Acid Distillate by Using PTSA as a Catalyst. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1003, 012134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlouli, A.; Mahdavian, L. Catalysts used in biodiesel production: A review. Biofuels 2021, 12, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Chauhan, G.; Chaurasia, S.P.; Singh, K. Study of catalytic behavior of KOH as homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2012, 43, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, I.M.R.; Ong, H.C.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Mofijur, M.; Silitonga, A.S.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Ahmad, A. State of the Art of Catalysts for Biodiesel Production. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabal, R. Advancements in catalysts; process intensification, and feedstock utilization for sustainable biodiesel production. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Devlin, G.; Deverell, R.; McDonnell, K. Potential to increase indigenous biodiesel production to help meet 2020 targets—An EU perspective with a focus on Ireland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, A.; Liakouli, N.C.; Fiotaki, C.; Pavlidis, I.V. Comparative Study of Immobilized Biolipasa-R for Second Generation Biodiesel Production from an Acid Oil. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Lohan, P.; Jha, P.N.; Mehrotra, R. Biodiesel production through lipase catalyzed transesterification: An overview. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010, 62, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyinyechukwu, J.C.; Christiana, N.O.; Chukwudi, O.; James, C.O. Lipase in biodiesel production. Afr. J. Biochem. Res. 2018, 12, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komintarachat, C.; Chuepeng, S. Methanol-Based Transesterification Optimization of Waste Used Cooking Oil over Potassium Hydroxide Catalyst. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 7, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohidem, N.A.; Mohamad, M.; Rashid, M.U.; Norizan, M.N.; Hamzah, F.; Mat, H.B. Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilisation Strategies: An Overview of Techniques and Composite Carriers. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, A.; Chi, K.B.; Trunov, D.; Sedlářová, I.; Belluati, A.; Šoóš, M. Effective lipase immobilization on crosslinked functional porous polypyrrole aggregates. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 667, 131362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béligon, V.; Poughon, L.; Christophe, G.; Lebert, A.; Larroche, C.; Fontanille, P. Validation of a predictive model for fed-batch and continuous lipids production processes from acetic acid using the oleaginous yeast Cryptococcus curvatus. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 111, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, S.; He, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Z.; Li, Z. A review of lipid accumulation by oleaginous yeasts: Culture mode. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreti, D.; Kosre, A.; Jadhav, S.K.; Chandrawanshi, N.K. A comprehensive review on oleaginous bacteria: An alternative source for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Solís, A.; Lobato-Calleros, O.; Moreno-Terrazas, R.; Lappe-Oliveras, P.; Neri-Torres, E. Biodiesel Production Processes with Yeast: A Sustainable Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Arora, N.; Sartaj, K.; Pruthi, V.; Pruthi, P.A. Sustainable biodiesel production from oleaginous yeasts utilizing hydrolysates of various non-edible lignocellulosic biomasses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 836–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, N.; Okeke, B.C. Modern Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Candia, D.E.; Pinzi, S.; Redel-Macías, M.D.; Koutinas, A.; Webb, C.; Dorado, M.P. The potential for agro-industrial waste utilization using oleaginous yeast for the production of biodiesel. Fuel 2014, 123, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donot, F.; Fontana, A.; Baccou, J.C.; Strub, C.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Single cell oils (SCOs) from oleaginous yeasts and moulds: Production and genetics. Biomass-Bioenergy 2014, 68, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuez, M.; Mahdy, A.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; González-Fernández, C.; Ballesteros, M. Enzymatic cell disruption of microalgae biomass in biorefinery processes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015, 112, 1955–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.E.; Loera-Corral, O.; Cañizares-Villanueva, R.O.; Aguilar-López, R.; Montes-Horcasitas, M.D.C. A critical review of challenges and advances to produce 2G biodiesel with oleaginous microorganisms and lignocellulose. ChemRxiv, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y. Biodiesels from microbial oils: Opportunity and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzler, S.; Steinbüchel, A. Establishment of Cellobiose Utilization for Lipid Production in Rhodococcus opacus PD630. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3122–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, H.M.; Souto, M.F.; Viale, A.; Pucci, O.H. Biosynthesis of fatty acids and triacylglycerols by 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl pentadecane-grown cells of Nocardia globerula 432. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 200, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arous, F.; Jaouani, A.; Mechichi, T. Oleaginous Microorganisms for Simultaneous Biodiesel Production and Wastewater Treatment. In Microbial Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, S.; Khalid, A.; Mahmood, S.; Anjum, M.; Ahmad, Z. Utilizing oleaginous bacteria and fungi for cleaner energy production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, G.O.; Faba, E.M.S.; Rickert, A.A.; Eimer, G.A. Alternatives to rethink tomorrow: Biodiesel production from residual and non-edible oils using biocatalyst technology. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, R.K.; Srivastava, S.; Thakur, I.S. Extraction of extracellular lipids from chemoautotrophic bacteria Serratia sp. ISTD04 for production of biodiesel. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 165, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simultaneous Utilization of Glucose and Xylose for Lipid Production by Trichosporon cutaneum. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1754-6834-4-25 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Kumar, D.; Singh, B.; Korstad, J. Utilization of lignocellulosic biomass by oleaginous yeast and bacteria for production of biodiesel and renewable diesel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 654–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigie, Y.A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Kasim, N.S.; Diem, Q.-D.; Huynh, L.-H.; Ho, Q.-P.; Truong, C.-T.; Ju, Y.-H. Oil Production from Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g Using Rice Bran Hydrolysate. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 378384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triacylglycerols in Prokaryotic Microorganisms. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-002-1135-0 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Single Cell Oil Production by Gordonia sp. DG Using Agro-Industrial Wastes. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11274-008-9664-z (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Shafie, S.M.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Masjuki, H.H.; Andriyana, A. Current energy usage and sustainable energy in Malaysia: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4370–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Yoo, C.; Jun, S.-Y.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Oh, H.-M. Comparison of several methods for effective lipid extraction from microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S75–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, S.N.; Marchetti, J.M. Economics of biodiesel production: Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 168, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadi, A.A.; Rahmati, S.; Fakhlaei, R.; Barati, B.; Wang, S.; Doherty, W.; Ostrikov, K. Emerging technologies for biodiesel production: Processes, challenges, and opportunities. Biomass-Bioenergy 2022, 163, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, G.; Aiswarya, R. Trends in catalytic production of biodiesel from various feedstocks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Trovão, J.P.F.; Solano, J. Fuzzy logic-model predictive control energy management strategy for a dual-mode locomotive. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 253, 115111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, V.F. Biodiesel production by supercritical methanol transesterification: Process simulation and potential environmental impact assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M.; García, I.L.; Papadaki, A.; Tsouko, E.; Koutinas, A.; Dorado, M.P. Biodiesel production using microbial lipids derived from food waste discarded by catering services. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Du, W.; Liu, D. Perspectives of microbial oils for biodiesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussul, N.; Deininger, K.; Shumilo, L.; Lavreniuk, M.; Ali, D.A.; Nivievskyi, O. Biophysical Impact of Sunflower Crop Rotation on Agricultural Fields. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammary, A.A.G.; Al-Shihmani, L.S.S.; Fernández-Gálvez, J.; Caballero-Calvo, A. Optimizing sustainable agriculture: A comprehensive review of agronomic practices and their impacts on soil attributes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact of Fertilizers on Aquatic Ecosystems and Protection of Water Bodies from Mineral Nutrients. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240641590_Impact_of_fertilizers_on_aquatic_ecosystems_and_protection_of_water_bodies_from_mineral_nutrients (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- SanzRequena, J.F.; Guimaraes, A.C.; Quirós Alpera, S.; Relea Gangas, E.; Hernandez-Navarro, S.; Navas Gracia, L.M.; Martin-Gil, J.; Fresneda Cuesta, H. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the biofuel production process from sunflower oil, rapeseed oil and soybean oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War Influence on Sunflower Seed and Oil Production in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.iitf.lbtu.lv/conference/proceedings2024/Papers/TF084.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Flagella, Z.; Monteleone, M. Perspectives on Sunflower as an Energy Crop. In Energy Crops; Halford, N.G., Karp, A., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A.; Skakun, S.; Becker-Reshef, I.; Kussul, N.; Shelestov, A. Estimation of sunflower planted areas in Ukraine during full-scale Russian invasion: Insights from Sentinel-1 SAR data. Sci. Remote Sens. 2024, 10, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, M. A Time Trend and Persistence Analysis of Sunflower Oil and Olive Oil Prices in the Context of the Russia-Ukraine War. Res. World Agric. Econ. 2024, 5, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, A.; Villalobos, P. Greenhouse gas emissions and energy balance of sunflower biodiesel: Identification of its key factors in the supply chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 73, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, M.; Kaungal, J. The Role of Economic and Social Factors Affecting the Efficiency of Small-Scale Sunflower Oil Production Companies in Tanzania. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2024, 21, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Biodiesel from sunflower oil in supercritical methanol with calcium oxide. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, H.S.; Tortola, D.S.; Reis, É.M.; Silva, J.L.; Taranto, O.P. Transesterification reaction of sunflower oil and ethanol for biodiesel synthesis in microchannel reactor: Experimental and simulation studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, D.L.; Constenla, D.T.; Raab, D. Effect of degumming process on physicochemical properties of sunflower oil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 6, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degumming of Rapeseed and Sunflower Oils. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237723818_Degumming_of_rapeseed_and_sunflower_oils (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Dakeso, T. The Status of Land Degradation Induced by Soil Erosion and Management Options in Duna District, Hadiya Zone, Central Ethiopia. Hydrology 2024, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, E.M.M.; Esteves, V.P.P.; Bungenstab, D.J.; Araújo, O.D.Q.F.; Morgado, C.D.R.V. Greenhouse gas emissions related to biodiesel from traditional soybean farming compared to integrated crop-livestock systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevali, A.; Hooshmandzadeh, N.; Fayyazi, E.; Valipour, M.; Yue, J. Environmental Impacts of Biodiesel Production Cycle from Farm to Manufactory: An Application of Sustainable Systems Engineering. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonza, C.; Nhamo, G. Institutional and regulatory framework for biodiesel production: International perspectives and lessons for South Africa. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.; Anwar, M.N.; Saif, H.; Tahir, E.; Tahir, A.; Rehan, M.; Tanveer, R.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Nizami, A.-S. Policy and regulatory constraints in the biodiesel production and commercialization. In Sustainable Biodiesel; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biodiesel Production: An Overview and Prospects for Sustainable Energy Generation. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372338426_Biodiesel_Production_An_Overview_and_Prospects_for_Sustainable_Energy_Generation (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Mizik, T.; Gyarmati, G. Economic and Sustainability of Biodiesel Production—A Systematic Literature Review. Clean Technol. 2021, 3, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issues in Biodiesel Production: A Review and an Approach for Design of Manufacturing Plant with Cost and Capacity Perspective. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309913053_Issues_in_Biodiesel_Production_A_Review_and_an_Approach_for_Design_of_Manufacturing_Plant_with_Cost_and_Capacity_Perspective (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Malik, M.A.I.; Zeeshan, S.; Khubaib, M.; Ikram, A.; Hussain, F.; Yassin, H.; Qazi, A. A review of major trends, opportunities, and technical challenges in biodiesel production from waste sources. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 23, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, M.; Quintella, C.M.; Ribeiro, E.M.O.; Silva, H.R.G.; Guimarães, A.K. Overview of the challenges in the production of biodiesel. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2015, 5, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroua, M.K.; Cognet, P. Editorial: From Glycerol to Value-Added Products. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Khilji, I.A.; Sirohi, R.; Pandey, A.; Baskar, G.; Satyavolu, J. Maximizing the value of biodiesel industry waste: Exploring recover, recycle, and reuse for sustainable environment. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, C.A.G.; Coronado, C.J.R.; Carvalho, J.A., Jr. Glycerol: Production, consumption, prices, characterization and new trends in combustion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, A.K.; Harikrishna, M.; Mahato, D.L.; Anandamma, U.; Pothu, R.; Sarangi, P.K.; Sahoo, U.K.; Vennu, V.; Boddula, R.; Karuna, M.S. Valorising orange and banana peels: Green catalysts for transesterification and biodiesel production in a circular bioeconomy. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 177, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Rukavishnikov, V.S.; Minaev, K.M. Review of technological progress in carbon dioxide capture, storage, and utilization. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 117, 205070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.B.; Avramović, J.M.; Stamenković, O.S. Biodiesel production by ultrasound-assisted transesterification: State of the art and the perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sundaram, S.; Gnansounou, E.; Larroche, C.; Thakur, I.S. Carbon dioxide capture, storage and production of biofuel and biomaterials by bacteria: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, W.W.S.; Ng, H.K.; Gan, S. Advances in ultrasound-assisted transesterification for biodiesel production. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 100, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chrzanowski, M.; Liu, Y. Ultrasonic-Assisted Transesterification: A Green Miniscale Organic Laboratory Experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O.; Kallon, D.V.V. Application of machine learning technologies in biodiesel production process—A review. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1122638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Bobadilla, M.; Lostado-Lorza, R.; Sabando-Fraile, C.; Íñiguez-Macedo, S. An artificial intelligence approach to model and optimize biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using life cycle assessment and market dynamics analysis. Energy 2024, 307, 132712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feedstock | Yield (MT/ha) | Crop Type | Sustainability Advantages | Sustainability Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palm oil | 3.3 | Perennial | Highest yield per hectare; efficient land productivity [22,23,26] | Deforestation, peatland CO2 release, biodiversity loss [22,23,26] |

| Sunflower | 1–3 | Annual | Adaptable to arid climates; balanced sustainability profile [12,13,25] | Land-intensive; moderate GHG footprint [13,25] |

| Soybean | 3.63 | Annual | Large-scale global availability; established industry [19,20,21] | High deforestation rates in Brazil/Argentina; high water footprint [19,21] |

| Rapeseed | 3 | Annual | Moderate yield; widely cultivated in temperate zones [24,26] | Seasonal variability; limited scalability [24,26] |

| Peanut | 1.8 | Annual | By-product use (dual food and& oil markets) [12,19] | Low yield; not scalable for biodiesel [12,19] |

| Type of Oil | Oil Yield (%) | Density (kg/m3) | Viscosity (mm2/s) | Cetane Number | Pour Point | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunflower oil | 25–55 | 918 | 34.01 | 38.1 | −10.8 | Concerns over food supply [47,50]. |

| Soybean oil | 20 | 916 | 31.83 | 38 | −10.5 | Loss of biodiversity and high water demand [47,49]. |

| Palm oil | 20 | 897 | 40.65 | 41 | 14.3 | Alterations in land use [47,49]. |

| Jatropha Curcas | 35–40 | 916 | 37.28 | 21 | −4 | Increased water demand, especially in dry areas [49,50]. |

| Waste Cooking oil | - | 887 | 4.63 | 59 | 4 | Reduces waste and widely available [47]. |

| Microalgae | 30–40 | 882 | 4.82 | 47 | −10 | Require intensive energy to be cultivated and large amounts of water [47,49,51]. |

| Region | Share of Global Biodiesel Production | Major Oils Used for Biodiesel Production | Key Demand Drivers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | ~30–32% | Rapeseed oil, sunflower oil | Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), decarbonization targets | [7,65] |

| United States | ~18–20% | Soybean oil | Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), tax incentives | [7,65] |

| Indonesia | ~15% | Palm oil | B30 blending mandate, energy security | [65] |

| Brazil | ~10–12% | Soybean oil | National biodiesel blending mandates (B10–B15) | [65] |

| Argentina | ~8–10% | Soybean oil | Export-driven biodiesel market, blending policies | [65] |

| Property | Sunflower Biodiesel (B100) | Petro-Diesel | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cetane Number | 49–55 | 45–50 | [65,66] |

| Kinematic Viscosity (mm2/s) | 4.0–5.5 | 1.9–4.1 | [67] |

| Density @ 15 °C (kg/m3) | 870–890 | 820–845 | [3,65] |

| Flash Point (°C) | 170–190 | 60–80 | [52,66] |

| Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | 37–39 | 42–45 | [65,66] |

| CO Emissions | ↓ 30–50% | Baseline | [69] |

| HC Emissions | ↓ 40–70% | Baseline | [69] |

| NOx Emissions | ↑ 5–15% | Baseline | [67,68] |

| Biodegradability | High (~95%) | Low (~30%) | [52,65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

El Marji, L.; Sharara, M.; El Chakik, D.; Nakad, M.; Assaf, J.C.; Estephane, J. A Comparative Review of Biomass Conversion to Biodiesel with a Focus on Sunflower Oil: Production Pathways, Sustainability, and Challenges. Processes 2026, 14, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030441

El Marji L, Sharara M, El Chakik D, Nakad M, Assaf JC, Estephane J. A Comparative Review of Biomass Conversion to Biodiesel with a Focus on Sunflower Oil: Production Pathways, Sustainability, and Challenges. Processes. 2026; 14(3):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030441

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Marji, Lea, Mohammad Sharara, Dana El Chakik, Mantoura Nakad, Jean Claude Assaf, and Jane Estephane. 2026. "A Comparative Review of Biomass Conversion to Biodiesel with a Focus on Sunflower Oil: Production Pathways, Sustainability, and Challenges" Processes 14, no. 3: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030441

APA StyleEl Marji, L., Sharara, M., El Chakik, D., Nakad, M., Assaf, J. C., & Estephane, J. (2026). A Comparative Review of Biomass Conversion to Biodiesel with a Focus on Sunflower Oil: Production Pathways, Sustainability, and Challenges. Processes, 14(3), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030441