Knowledge-Enhanced Time Series Anomaly Detection for Lithium Battery Cell Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

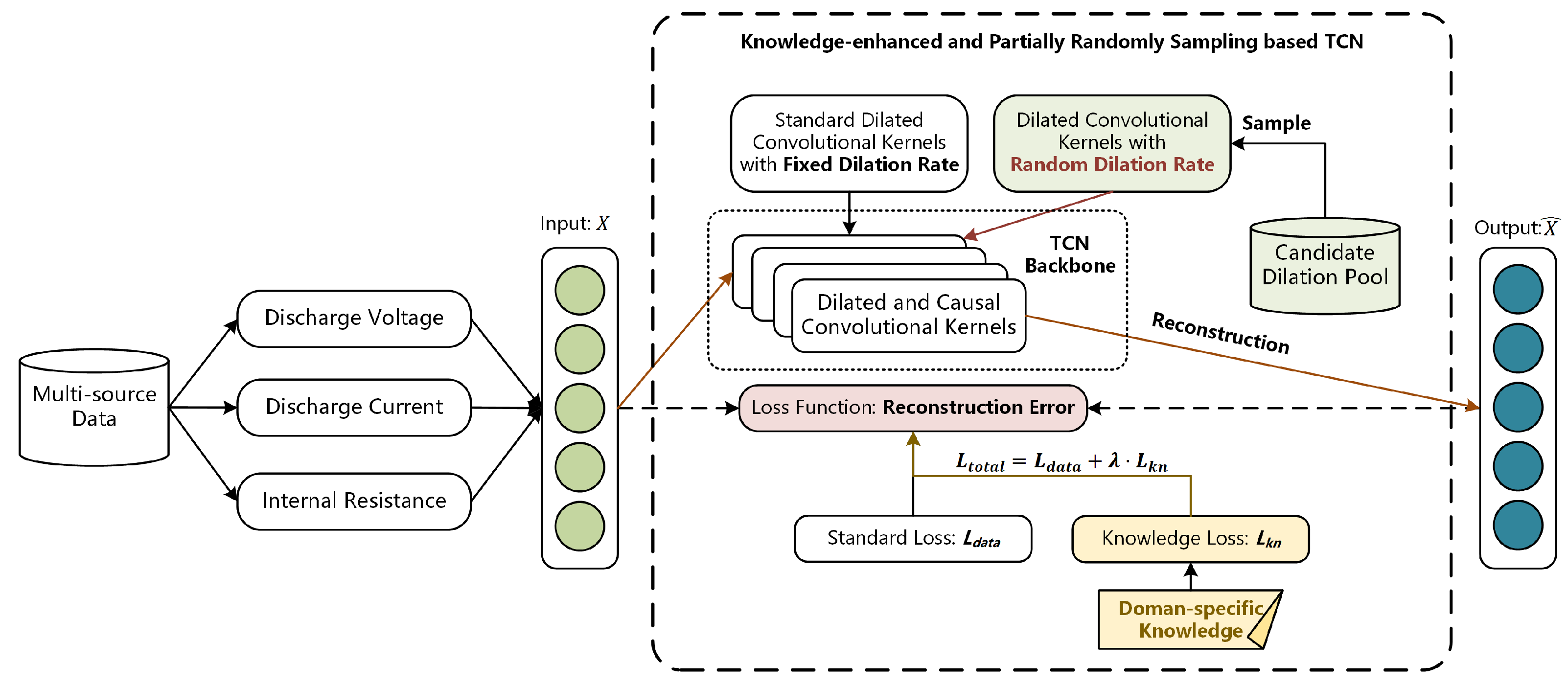

- Development of a TCN-based anomaly detection framework: We introduce a novel time-series anomaly detection framework based on the Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), which effectively handles long-range dependencies and overcomes the issue of blind spots of convolutional kernels by using randomly sampled dilated convolution kernels.

- 2.

- Knowledge-enhanced regularization for improved model interpretability: We propose a knowledge-enhanced approach that encodes manufacturing domain knowledge into the model’s loss function as the regularization terms. This additional knowledge constraint improves model robustness and interpretability, particularly in identifying subtle anomalies that may not be captured by data-driven methods alone.

- 3.

- We validate our method on real-world industrial datasets, demonstrating significant improvements in detection performance over existing baselines.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. TCN and Blind Spot

3.1.1. Temporal Dependency Acquisition

3.1.2. Blind Spot Phenomenon

3.2. Partially Randomly Sampling

3.3. Knowledge-Enhanced Regularization

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Dataset Description

4.2. Experimental Setup

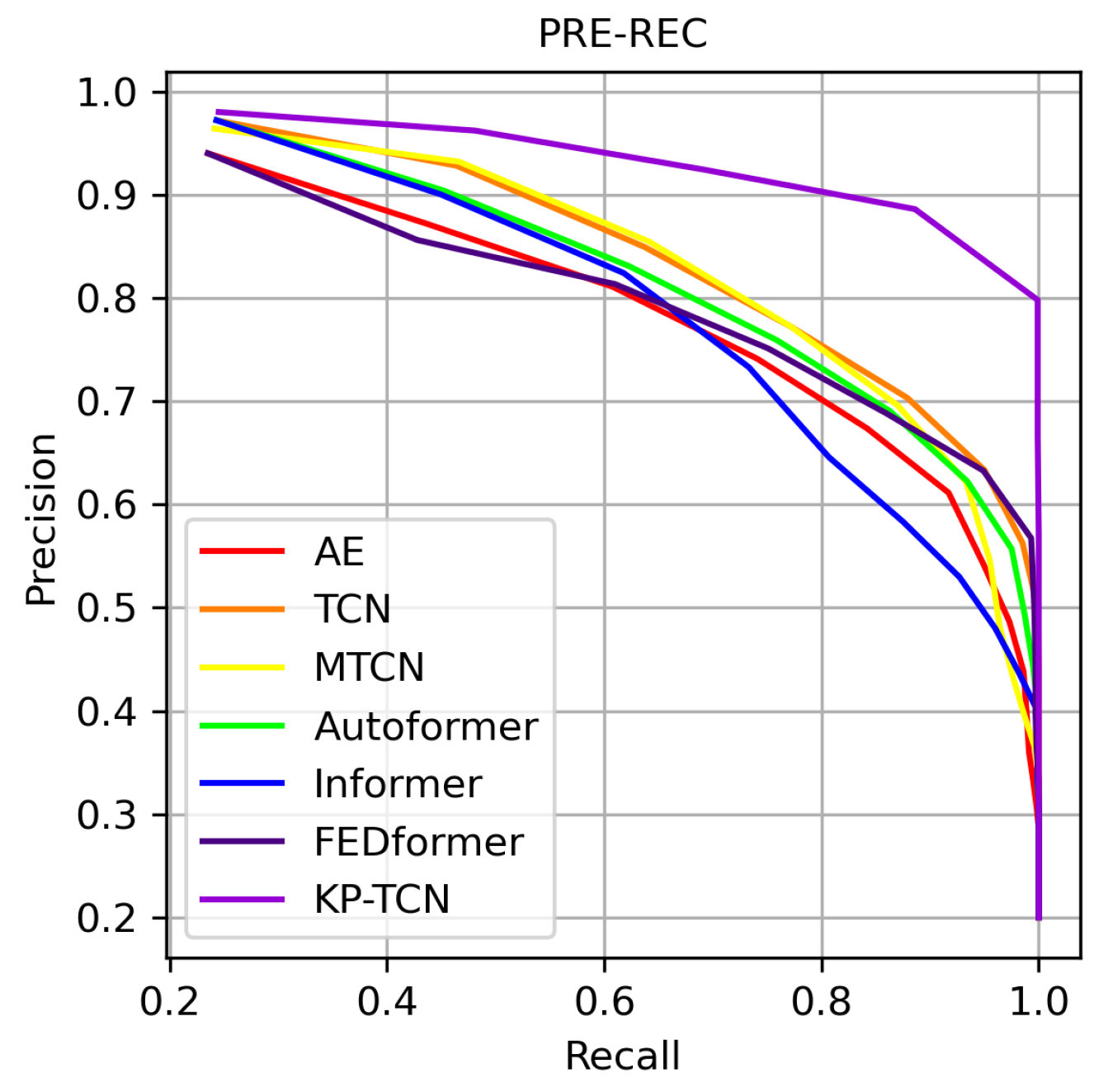

4.3. Main Results

4.3.1. Convergency

4.3.2. Detailed Results

- 1.

- When equals 0.2, the number of samples labeled as anomalies in each detection is 1000 (20% of the 5000-test sample set).

- 2.

- When is less than 0.2, the number of samples labeled as anomalies is smaller than the actual number of anomalies in the test set (1000).

4.4. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- Partially random sampling mechanism: This mechanism effectively avoids the blind spot problem of convolutional kernels, preventing the TCN from missing critical features when capturing data patterns.

- 2.

- Knowledge-enhanced regularization: By leveraging prior knowledge, this component enables the model to learn richer intrinsic patterns from normal samples.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Bai, X.; Liu, C.; Tan, J. A multi-source data feature fusion and expert knowledge integration approach on lithium-ion battery anomaly detection. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2022, 19, 021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Liu, Z.; Ditta, A. Lithium-ion Battery Screening by K-means with Dbscan for Denoising. CMC-Comput. Mater. Cont. 2020, 65, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Kong, X.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Gao, P.; Li, Y.; et al. Detecting the foreign matter defect in lithium-ion batteries based on battery pilot manufacturing line data analyses. Energy 2023, 262, 125502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Mohon, S.; Pisu, P.; Ayalew, B. Sensor fault detection, isolation, and estimation in lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W. A Framework for Anomaly Cell Detection in Energy Storage Systems Based on Daily Operating Voltage and Capacity Increment Curves. Batteries 2025, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Lenz, E.; Gulla, D.; Bazant, M.Z.; Braatz, R.D.; Findeisen, R. Lithium-Ion Battery System Health Monitoring and Fault Analysis from Field Data Using Gaussian Processes. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.19015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Yang, D.; Lyu, C.; Ma, J.; Hinds, G.; Sun, Q.; Du, L.; Wang, L. Multi-sensor multi-mode fault diagnosis for lithium-ion battery packs with time series and discriminative features. Energy 2024, 290, 130151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukerche, A.; Zheng, L.; Alfandi, O. Outlier detection: Methods, models, and classification. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh Darban, Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.; Salehi, M. Deep learning for time series anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidl, S.; Wenig, P.; Papenbrock, T. Anomaly detection in time series: A comprehensive evaluation. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2022, 15, 1779–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Shen, C.; Cao, L.; Hengel, A.V.D. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Pan, X.; Li, N.; He, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, N. GAN-based anomaly detection: A review. Neurocomputing 2022, 493, 497–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, L. Survey of Lithium-Ion Battery Anomaly Detection Methods in Electric Vehicles. In IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Lin, M. Model-based thermal anomaly detection for lithium-ion batteries using multiple-model residual generation. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhu, E. Improved autoencoder for unsupervised anomaly detection. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 7103–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.K.; Su, Z.; Wu, J.; Tan, P.S.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y.H. Anomaly detection of defects on concrete structures with the convolutional autoencoder. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 45, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; He, Z.; Lin, H.; Cai, L.; Cai, H.; Gao, M. Anomaly detection of power battery pack using gated recurrent units based variational autoencoder. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 132, 109903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; Liao, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, L. Data-driven strategy: A robust battery anomaly detection method for short circuit fault based on mixed features and autoencoder. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Lin, S.; Cui, P.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y. adVAE: A self-adversarial variational autoencoder with Gaussian anomaly prior knowledge for anomaly detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 190, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossai, C.I.; Egwutuoha, I.P. Anomaly detection and extra tree regression for assessment of the remaining useful life of lithium-ion battery. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Caserta, Italy, 15–17 April 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1474–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Sun, H.; Takeuchi, M.; Katto, J. Deep convolutional autoencoder-based lossy image compression. In Proceedings of the 2018 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Arbaoui, S.; Samet, A.; Ayadi, A.; Mesbahi, T.; Boné, R. Data-driven strategy for state of health prediction and anomaly detection in lithium-ion batteries. Energy AI 2024, 17, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Xiong, N.N. Anomaly detection based on convolutional recurrent autoencoder for IoT time series. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2020, 52, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, X. Moderntcn: A modern pure convolution structure for general time series analysis. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbert, R.; Odonnat, A.; Feofanov, V.; Virmaux, A.; Paolo, G.; Palpanas, T.; Redko, I. SAMformer: Unlocking the Potential of Transformers in Time Series Forecasting with Sharpness-Aware Minimization and Channel-Wise Attention. In Machine Learning Research, Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 235, pp. 20924–20954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 27268–27286. [Google Scholar]

| Method | AE | TCN | MTCN | Autoformer | Informer | FEDformer | KP-TCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 16.4 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 23.12 | 31.3 | 27.8 | 7.9 |

| = | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | PRE | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.933 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.872 | 0.811 | 0.741 | 0.673 | 0.611 | 0.542 | 0.486 | 0.438 | 0.395 |

| REC | 0.047 | 0.094 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.235 | 0.436 | 0.608 | 0.741 | 0.842 | 0.917 | 0.949 | 0.973 | 0.986 | 0.989 | |

| TCN | PRE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.985 | 0.976 | 0.928 | 0.849 | 0.771 | 0.703 | 0.633 | 0.563 | 0.499 | 0.444 | 0.4 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.197 | 0.244 | 0.464 | 0.637 | 0.771 | 0.879 | 0.95 | 0.985 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 | |

| MTCN | PRE | 1 | 0.99 | 0.973 | 0.97 | 0.964 | 0.932 | 0.855 | 0.772 | 0.696 | 0.622 | 0.546 | 0.482 | 0.434 | 0.395 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.099 | 0.146 | 0.194 | 0.241 | 0.466 | 0.641 | 0.772 | 0.87 | 0.933 | 0.955 | 0.964 | 0.976 | 0.987 | |

| Autoformer | PRE | 1 | 1 | 0.987 | 0.98 | 0.968 | 0.904 | 0.831 | 0.759 | 0.690 | 0.623 | 0.557 | 0.494 | 0.442 | 0.399 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.148 | 0.196 | 0.242 | 0.452 | 0.623 | 0.759 | 0.863 | 0.934 | 0.975 | 0.987 | 0.995 | 0.999 | |

| Informer | PRE | 1 | 1 | 0.993 | 0.985 | 0.972 | 0.9 | 0.824 | 0.733 | 0.646 | 0.583 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.436 | 0.399 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.149 | 0.197 | 0.243 | 0.45 | 0.618 | 0.733 | 0.807 | 0.875 | 0.927 | 0.96 | 0.982 | 0.999 | |

| FEDformer | PRE | 1 | 1 | 0.987 | 0.965 | 0.94 | 0.856 | 0.813 | 0.751 | 0.688 | 0.633 | 0.567 | 0.498 | 0.443 | 0.398 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.148 | 0.193 | 0.235 | 0.428 | 0.61 | 0.751 | 0.86 | 0.949 | 0.993 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.997 | |

| KP-TCN | PRE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.995 | 0.98 | 0.962 | 0.924 | 0.886 | 0.798 | 0.666 | 0.571 | 0.5 | 0.444 | 0.4 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.199 | 0.245 | 0.481 | 0.693 | 0.886 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCN | PRE | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.933 | 0.95 | 0.976 | 0.928 | 0.849 | 0.772 | 0.703 | 0.6333 | 0.5629 | 0.499 |

| REC | 0.047 | 0.094 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.244 | 0.464 | 0.637 | 0.772 | 0.879 | 0.95 | 0.985 | 0.999 | |

| PRS-TCN | PRE | 1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.975 | 0.98 | 0.944 | 0.873 | 0.814 | 0.738 | 0.657 | 0.571 | 0.5 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.098 | 0.147 | 0.195 | 0.245 | 0.472 | 0.655 | 0.814 | 0.922 | 0.986 | 0.999 | 1 | |

| KE-TCN | PRE | 1 | 1 | 0.993 | 0.98 | 0.978 | 0.948 | 0.889 | 0.829 | 0.72 | 0.637 | 0.565 | 0.5 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.149 | 0.196 | 0.244 | 0.474 | 0.667 | 0.829 | 0.901 | 0.956 | 0.989 | 1 | |

| KP-TCN | PRE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.995 | 0.98 | 0.962 | 0.924 | 0.886 | 0.798 | 0.666 | 0.571 | 0.5 |

| REC | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.199 | 0.245 | 0.481 | 0.693 | 0.886 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, J. Knowledge-Enhanced Time Series Anomaly Detection for Lithium Battery Cell Screening. Processes 2026, 14, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020371

Liu Z, Wang Y, He J. Knowledge-Enhanced Time Series Anomaly Detection for Lithium Battery Cell Screening. Processes. 2026; 14(2):371. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020371

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhenjie, Yudong Wang, and Jianjun He. 2026. "Knowledge-Enhanced Time Series Anomaly Detection for Lithium Battery Cell Screening" Processes 14, no. 2: 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020371

APA StyleLiu, Z., Wang, Y., & He, J. (2026). Knowledge-Enhanced Time Series Anomaly Detection for Lithium Battery Cell Screening. Processes, 14(2), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020371