Numerical and Performance Optimization Research on Biphase Transport in PEMFC Flow Channels Based on LBM-VOF

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Reconstruction of Two-Phase Interfaces

2.2. Boundary Conditions and Initial Conditions

2.3. Model Validation

2.4. Grid Independence Validation

3. Results

3.1. Effect of GC Structure on Gas Velocity Distribution

3.2. Effect of GL Structure on Water Management

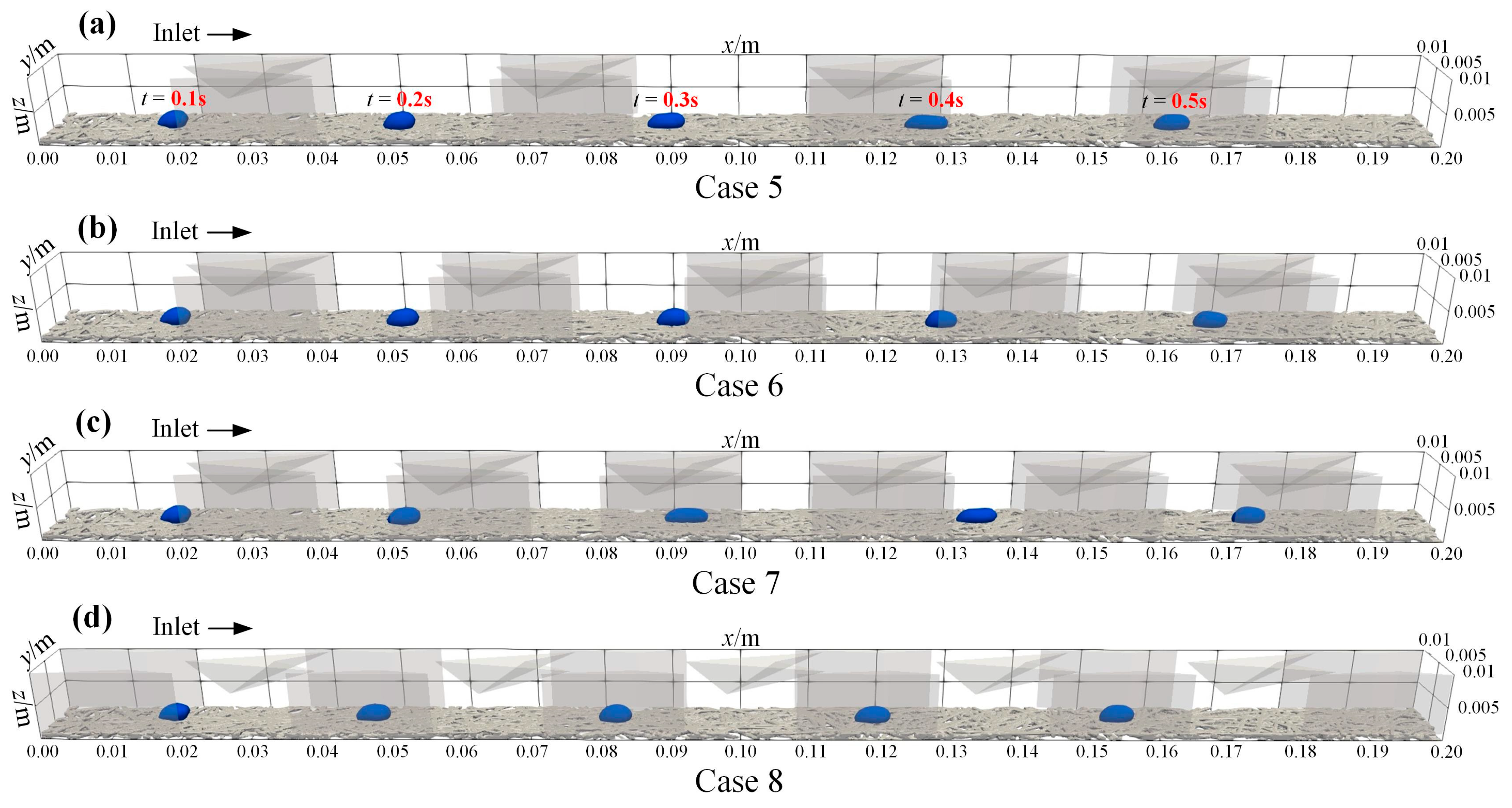

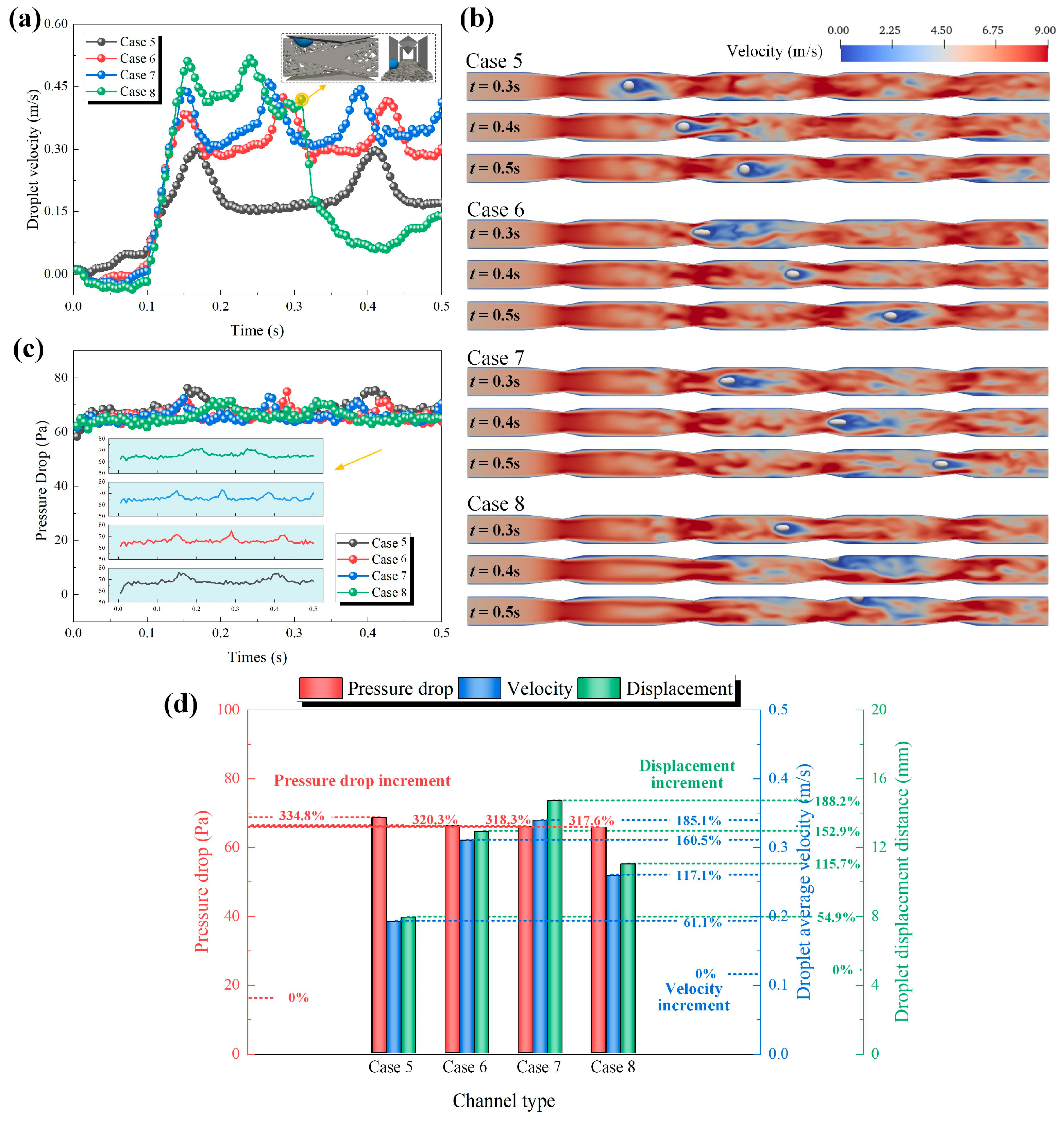

3.3. Effect of Block Spacing on Multiphase Flow in GC

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiao, K.; Xuan, J.; Du, Q.; Bao, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, L.H.; Wang, H.Z.; Hou, Z.J.; et al. Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 2021, 595, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Moon Kim, S.; Sik Kang, Y.; Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Kim, M.; Park, H.; Bang, J.W.; Seo, S.; Suh, K.Y.; et al. Multiplex lithography for multilevel multiscale architectures and its application to polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, D.A.; Neyerlin, K.C.; Ahluwalia, R.K.; Mukundan, R.; More, K.L.; Borup, R.L.; Weber, A.Z.; Myers, D.J.; Kusoglu, A. New roads and challenges for fuel cells in heavy-duty transportation. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Swihart, M.T.; Wu, G. Achievements, challenges and perspectives on cathode catalysts in proton exchange membrane fuel cells for transportation. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Meyer, Q.; Tang, K.; McClure, J.E.; White, R.T.; Kelly, S.T.; Crawford, M.M.; Iacoviello, F.; Brett, D.J.L.; Shearing, P.R.; et al. Large-scale physically accurate modelling of real proton exchange membrane fuel cell with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, A.J.; Gómez, M.A.; Daza, L.; López-Cascales, J.J. Production of gas diffusion layers with cotton fibers for their use in fuel cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Kas, R.; Smith, W.A.; Burdyny, T. Role of the carbon-based gas diffusion layer on flooding in a gas diffusion electrode cell for electrochemical CO2 reduction. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 6, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lin, C.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Wei, G.; Zhang, J. Effect of clamping pressure on liquid-cooled PEMFC stack performance considering inhomogeneous gas diffusion layer compression. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblett, D.; Mularczyk, A.; Niasar, V.; Eller, J.; Holmes, S. Two-phase flow dynamics in a gas diffusion layer-gas channel-microporous layer system. J. Power Sources 2020, 471, 228427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, W.; Bai, Y.F.; Zhao, Y.H.; Liu, Z.A.; Lin, Z.H.; Li, X.Z.; Wang, Y.A.; Tang, Y. Performance enhancement of proton exchange membrane fuel cells with bio-inspired gear-shaped flow channels. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.H.; Jung, S.M.; Park, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.K.; Son, J.; Kim, Y.T. Enhancing durability of automotive fuel cells via selective electrical conductivity induced by tungsten oxide layer coated directly on membrane electrode assembly. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozden, A.; Shahgaldi, S.; Li, X.; Hamdullahpur, F. A review of gas diffusion layers for proton exchange membrane fuel cells—With a focus on characteristics, characterization techniques, materials and designs. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 74, 50–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chang, G.; Fan, R.; Cai, T. Effects of various operating conditions and optimal ionomer-gradient distribution on temperature-driven water transport in cathode catalyst layer of PEMFC. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hou, T.; Jiang, J.; Grigoriev, S.A.; Fan, F.; Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, C. Thermal management of liquid-cooled proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A review. J. Power Sources 2025, 648, 237227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atz, K.; Grisoni, F.; Schneider, G. Geometric deep learning on molecular representations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Tang, M. Study on the characteristics of GDL with different PTFE content and its effect on the performance of PEMFC. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 128, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atyabi, S.A.; Afshari, E.; Wongwises, S.; Yan, W.M.; Hadjadj, A.; Shadloo, M.S. Effects of assembly pressure on PEM fuel cell performance by taking into accounts electrical and thermal contact resistances. Energy 2019, 179, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Fang, L.; Guo, H.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y. A bifunctional liquid fuel cell coupling power generation and V3.5+ electrolytes production for all vanadium flow batteries. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirsath, A.V.; Bonnet, C.; Arora, D.; Raël, S.; Lapicque, F. Characterization of water transport and flooding conditions in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells by electrochemical pressure impedance spectroscopy (EPIS). Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 190, 122767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakni, O.; Kerkoub, Y.; Amrouche, F.; Mohammedi, A.; Ziari, Y.K. CFD investigation of the effect of flow field channel design based on constriction and enlargement configurations on PEMFC performance. Fuel 2024, 357, 129920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, Q.; Yi, Z.; Huang, Y. Numerical investigation on the performance enhancement of PEMFC with gradient sinusoidal-wave fins in cathode channel. Energy 2024, 288, 129894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Yin, Z.; Tan, D. Numerical investigation of mesoscale multiphase mass transport mechanism in fibrous porous media. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2024, 18, 2363246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yang, M.; Sun, C.; Xu, S. Liquid water characteristics in the compressed gradient porosity gas diffusion layer of proton exchange membrane fuel cells using the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Energies 2023, 16, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Sun, C.; Mei, J.; Tang, X.; Hasanien, H.M.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; Song, K. Fuel cell life prediction considering the recovery phenomenon of reversible voltage loss. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gray, K.E. XFEM-based cohesive zone approach for modeling near-wellbore hydraulic fracture complexity. Acta Geotech. 2019, 14, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Li, L.; Tan, Y.F. Energy transfer characteristics of surface vortex heat flow under non-isothermal conditions based on the lattice Boltzmann method. Processes 2026, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.C.; Wan, Q.J.; Tan, D.P. Analytical treatment and experimental investigation of forced displacement responses of cracked fluid-filled thin cylindrical shells. Thin Wall Struct. 2026, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Hang, W.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A novel in-situ sensor calibration method for building thermal systems based on virtual samples and autoencoder. Energy 2024, 297, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, P.; Li, Q.; Zheng, R.; Wu, N.; Bao, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, Q.; Yin, Z. Fluid-induced energy transfer and vibration modes of multiphase mixing in static mixers across flow regime transitions. Chem. Eng. J. 2026, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M.; Song, C.; Yang, X.; Tang, H.P. Enhancing the mechanical behaviors of 18Ni300 steel through microstructural evolution in electron beam powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 4215–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, T.; Yao, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Qi, H.; Tang, H.P. Surface enhancement by micro-arc oxidation induced TiO2 ceramic coating on additive manufacturing Ti-6Al-4V. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 100190, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Anyanwu, I.S.; Niu, Z.; Jiao, D.; Najmi, A.U.H.; Liu, Z.; Jiao, K. Liquid Water Transport Behavior at GDL-Channel Interface of a Wave-Like Channel. Energies 2020, 13, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadrezaei, S.; Siavashi, M.; Asiaei, S. Surface topography effects on dynamic behavior of water droplet over a micro-structured surface using an improved-VOF based lattice Boltzmann method. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias van Montfort, H.P.; Li, M.; Irtem, E.; Abdinejad, M.; Wu, Y.; Pal, S.K.; Sassenburg, M.; Ripepi, D.; Subramaian, S.; Biemolt, J.; et al. Non-invasive current collectors for improved current-density distribution during CO2 electrolysis on super-hydrophobic electrodes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wen, Q.; Ning, F.; Shen, M.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, B.; Pan, S.; Dan, X.; Li, W.; et al. A new integrated GDL with wavy channel and tunneled rib for high power density PEMFC at low back pressure and wide humidity. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2302928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Geng, K.; Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; You, W.; Yan, F.; Guiver, M.D.; Li, N. Fuel cells with an operational range of −20 °C to 200 °C enabled by phosphoric acid-doped intrinsically ultramicroporous membranes. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Liu, L. Lattice Boltzmann simulations of micron-scale drop impact on dry surfaces. J. Comput. Phys. 2010, 229, 8045–8063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Weng, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, P.; Xu, W.; Li, L.; Xu, X.F.; Tan, D. Piezoelectric ultrasonic coupling-based polishing of micro-tapered holes with abrasive flow. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ding, M.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Z. A Novel Singular and Harmonics-to-Noise Ratio Deconvolution for Fault Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3556012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, R.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Xie, Y.; Tan, D.P. Coupled Design of Cathode GC and GDL Microporous Structure for Enhanced Mass Transport and Electrochemical Efficiency in PEMFCs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Type | Block Type | Block Spacing | GDL Surface Wettability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | / | / | 90° |

| Case 2 | FS block × 4 | 2.5 mm | 90° |

| Case 3 | SR block × 4 | 2.5 mm | 90° |

| Case 4 | FS block × 4, SR block × 4 | 2.5 mm | 90° |

| Case 5 | FS block × 4, SR block × 4 | 2.5 mm | 130° |

| Case 6 | FS block × 5, SR block × 5 | 1.5 mm | 130° |

| Case 7 | FS block × 6, SR block × 6 | 1 mm | 130° |

| Case 8 | FS block × 5, SR block × 5(interlacing) | 1.5 mm | 130° |

| Medium | Density (kg/m3) | Kinematic Viscosity (m2/s) | Dynamic Viscosity (Pa·s) | Surface Tension (N·m−1) | Contact Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 998.2 | 1.01 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−3 | 7.3 × 10−2 | 90/130 |

| Air | 1.225 | 1.48 × 10−5 | 1.79 × 10−5 |

| Grid Size | Numerical (°) | Analytical (°) | Bulk Density (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 × 25 × 25 | 77.23° | 80° | −3.47% |

| 1000 × 50 × 50 | 79.22° | −0.97% | |

| 1300 × 65 × 65 | 79.71° | −0.36% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Zheng, R.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Xie, Y.; Tan, D. Numerical and Performance Optimization Research on Biphase Transport in PEMFC Flow Channels Based on LBM-VOF. Processes 2026, 14, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020360

Li Z, Zheng R, Wang C, Li L, Xie Y, Tan D. Numerical and Performance Optimization Research on Biphase Transport in PEMFC Flow Channels Based on LBM-VOF. Processes. 2026; 14(2):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020360

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhe, Runyuan Zheng, Chengyan Wang, Lin Li, Yuanshen Xie, and Dapeng Tan. 2026. "Numerical and Performance Optimization Research on Biphase Transport in PEMFC Flow Channels Based on LBM-VOF" Processes 14, no. 2: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020360

APA StyleLi, Z., Zheng, R., Wang, C., Li, L., Xie, Y., & Tan, D. (2026). Numerical and Performance Optimization Research on Biphase Transport in PEMFC Flow Channels Based on LBM-VOF. Processes, 14(2), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020360