Energy Evolution of Far-Field Surrounding Rock Under True Triaxial Compression Conditions: Taking Fissured Sandstone as an Example

Abstract

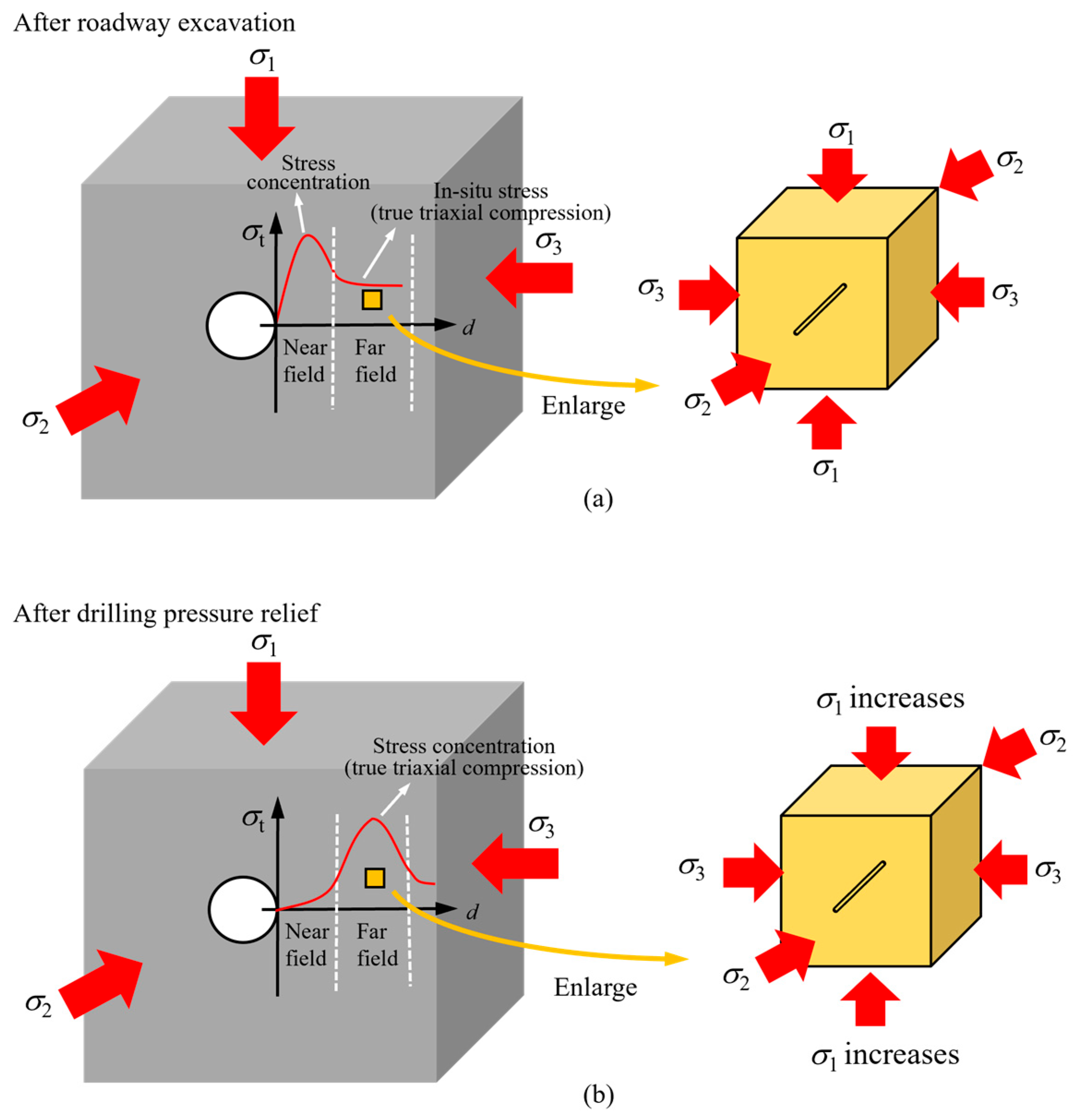

1. Introduction

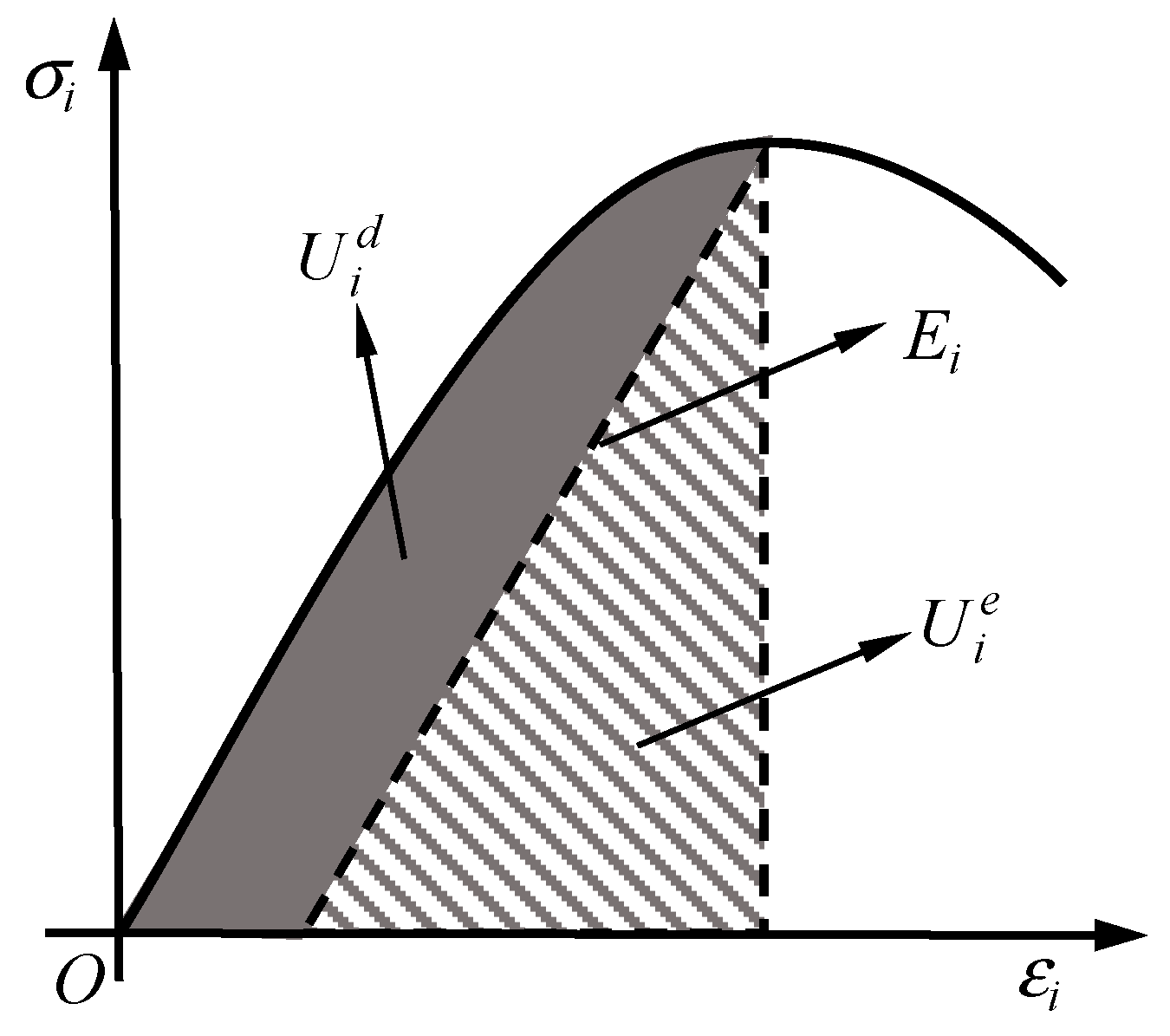

2. Energy Calculation Method

3. Energy Consumption Analysis in the Process of Rock Mass Failure

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Energy Evolution Law of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Fissure Dip Angles

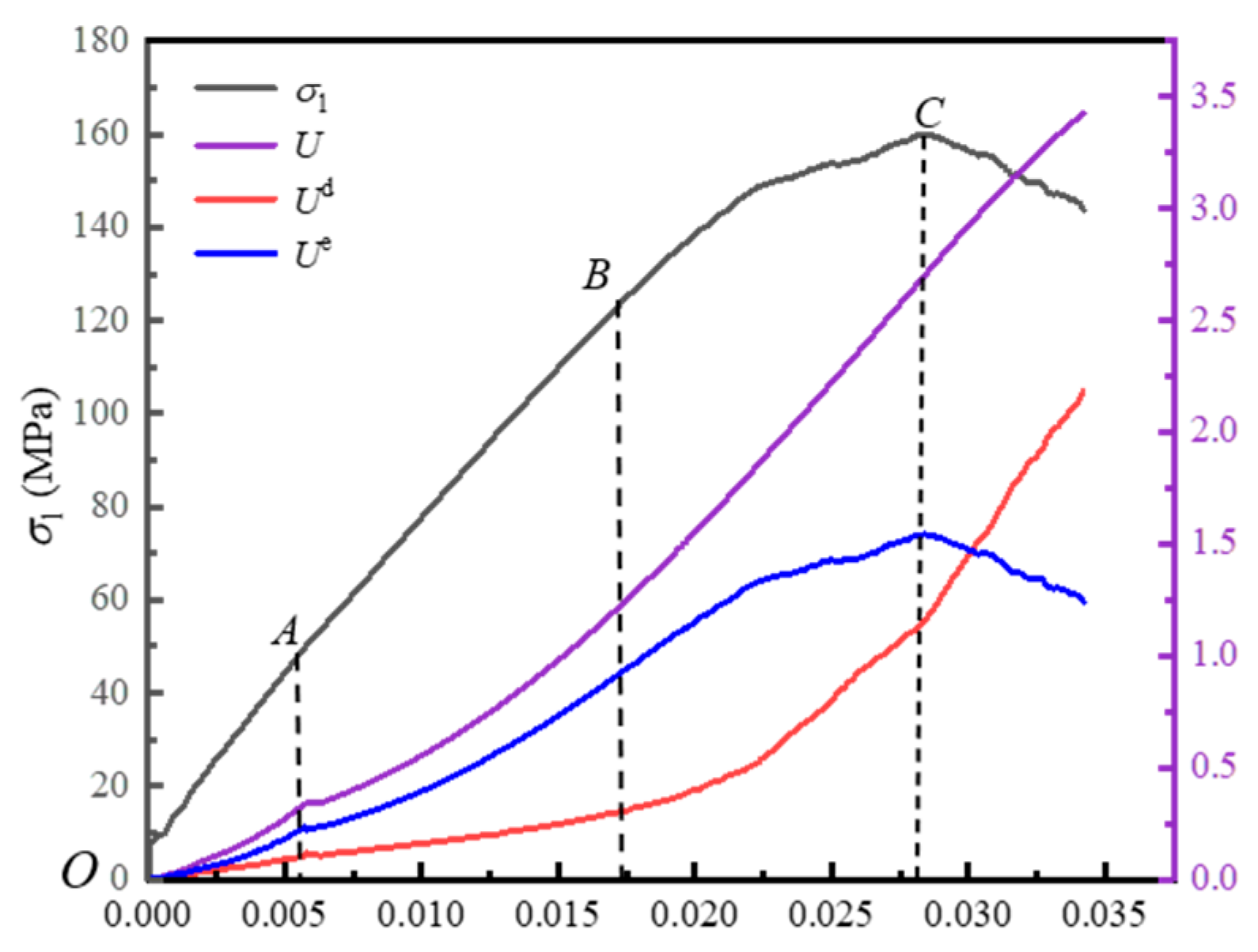

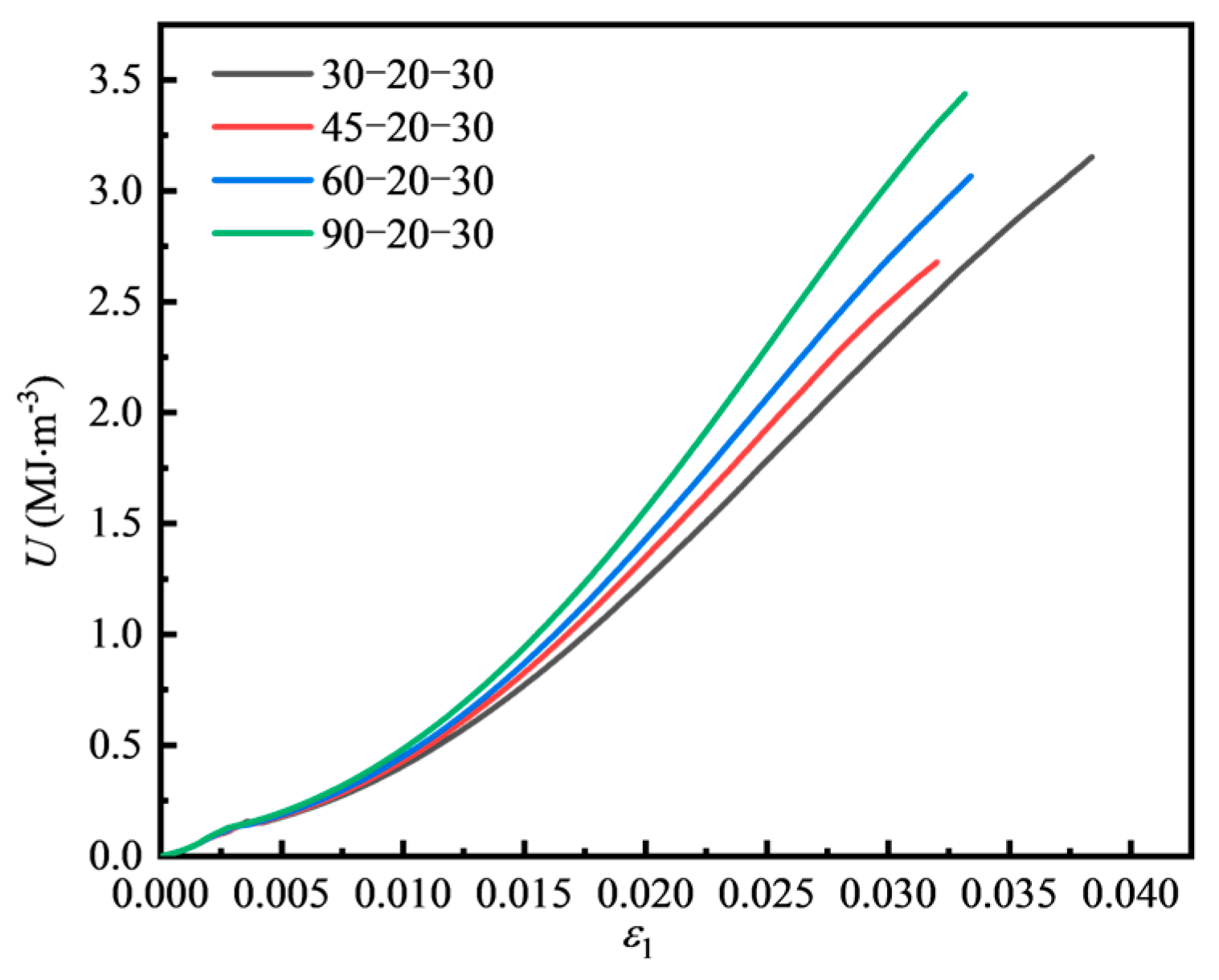

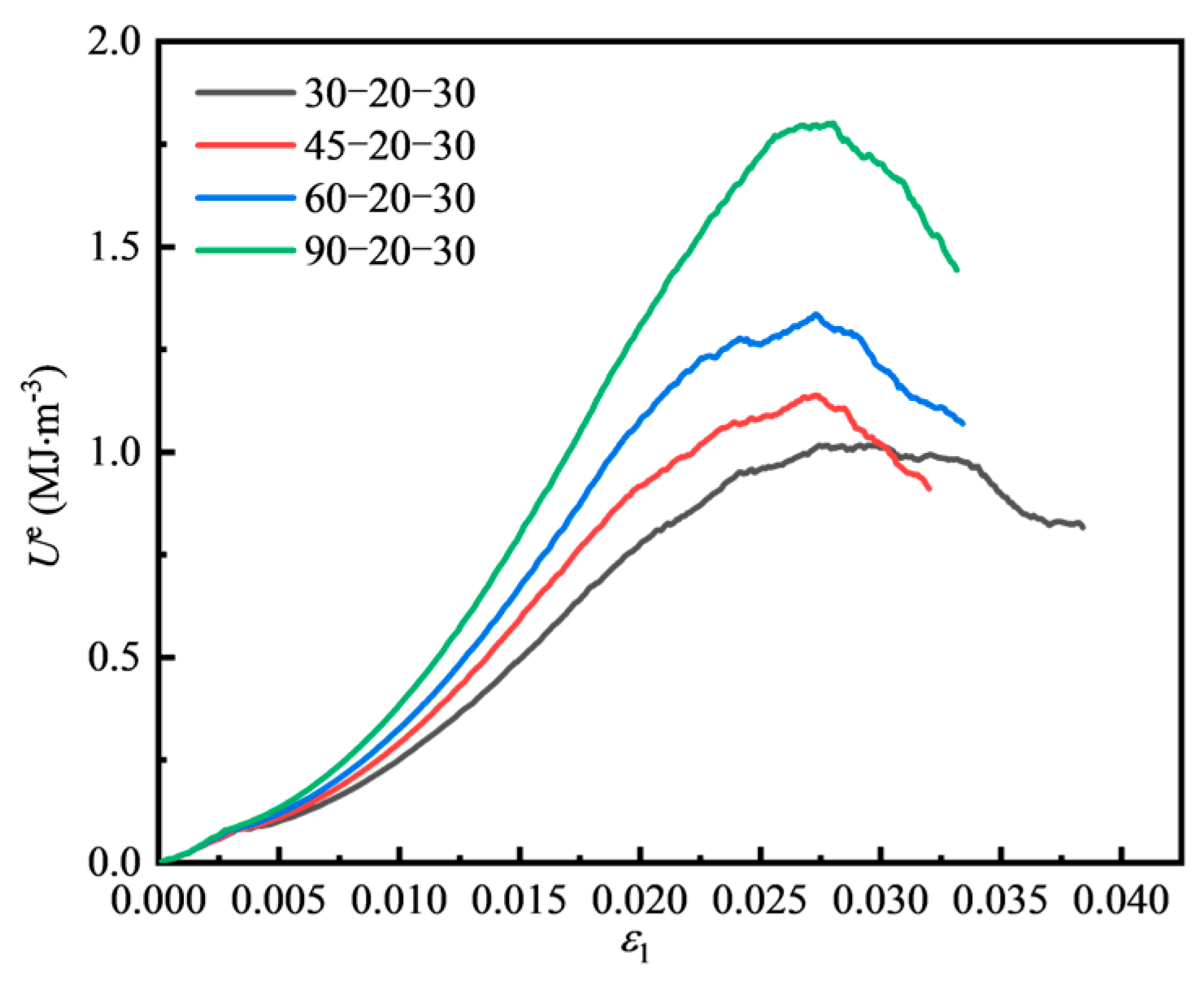

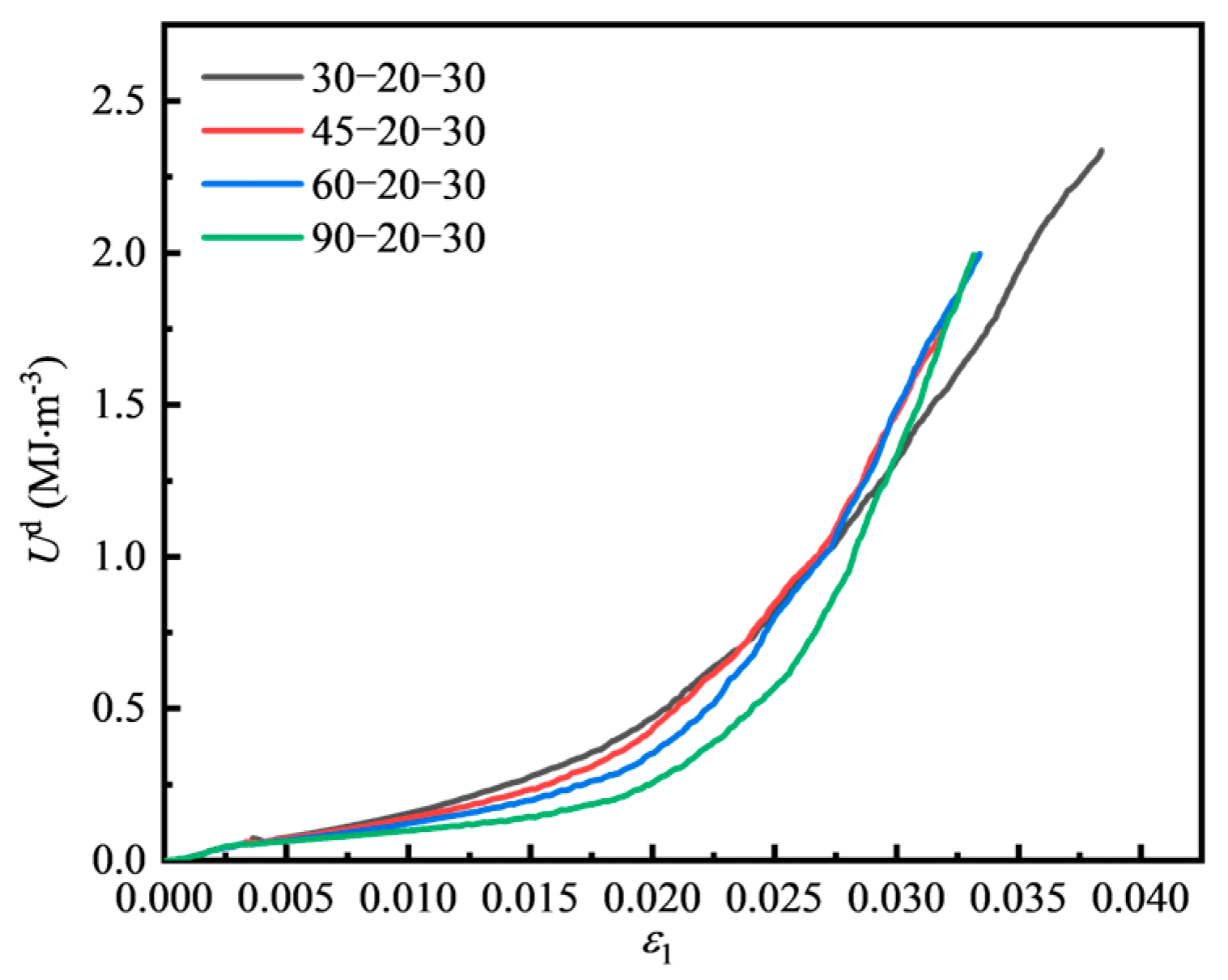

4.1.1. Energy Evolution of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Fissure Dip Angles

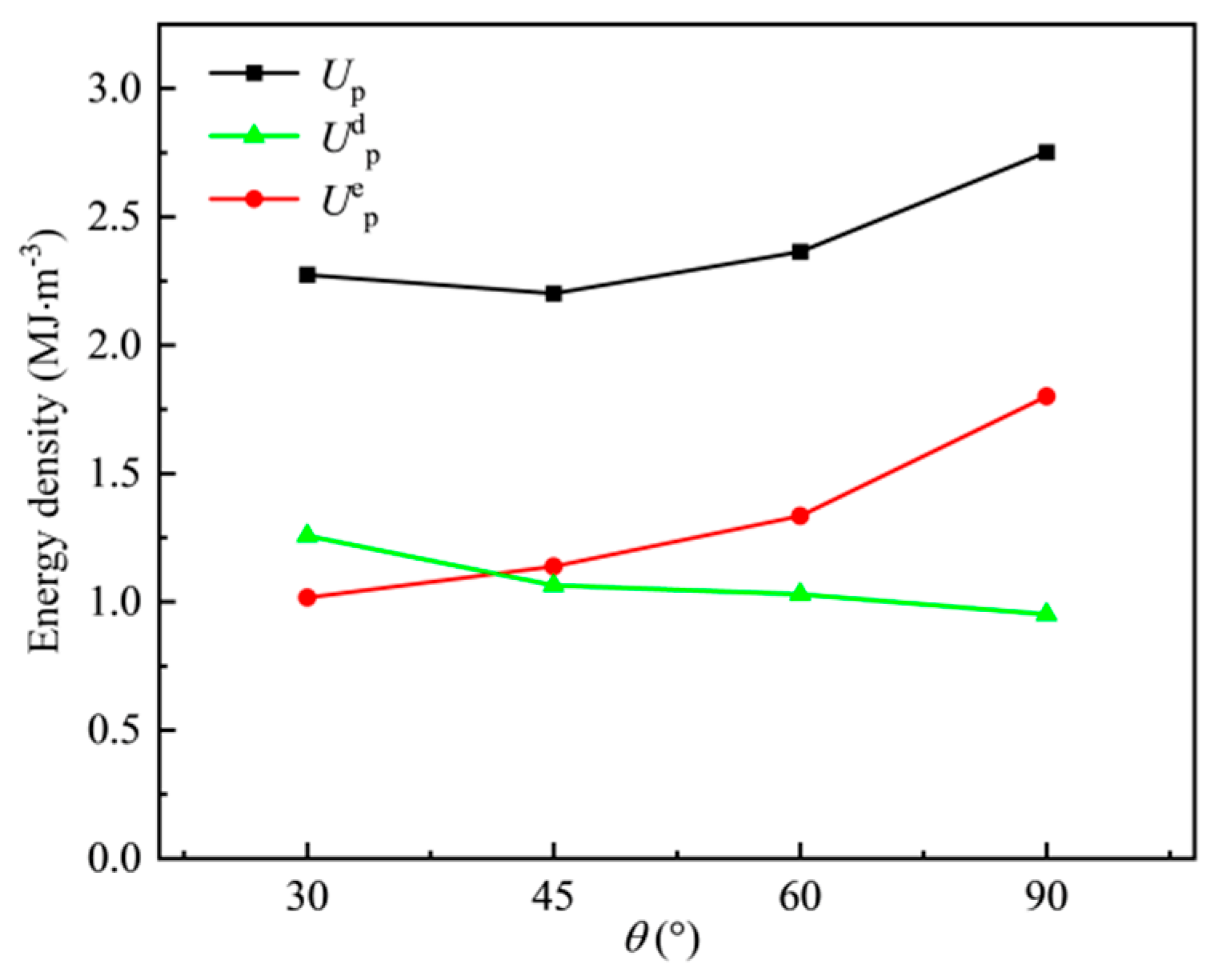

4.1.2. Energy Variation at Peak Strength Under Different Fissure Dip Angles

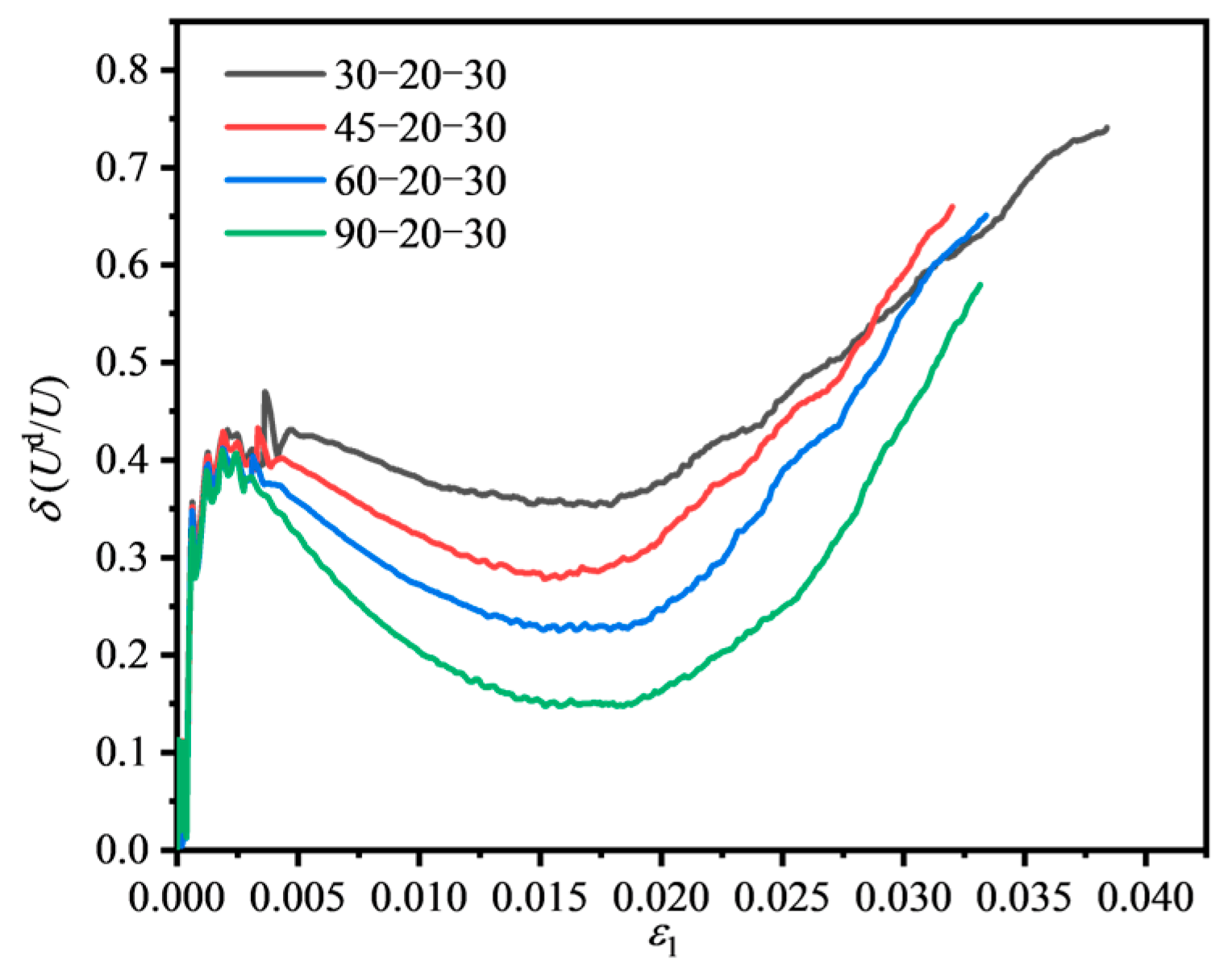

4.1.3. Variation in Dissipated Energy Ratio Under Different Fissure Dip Angles

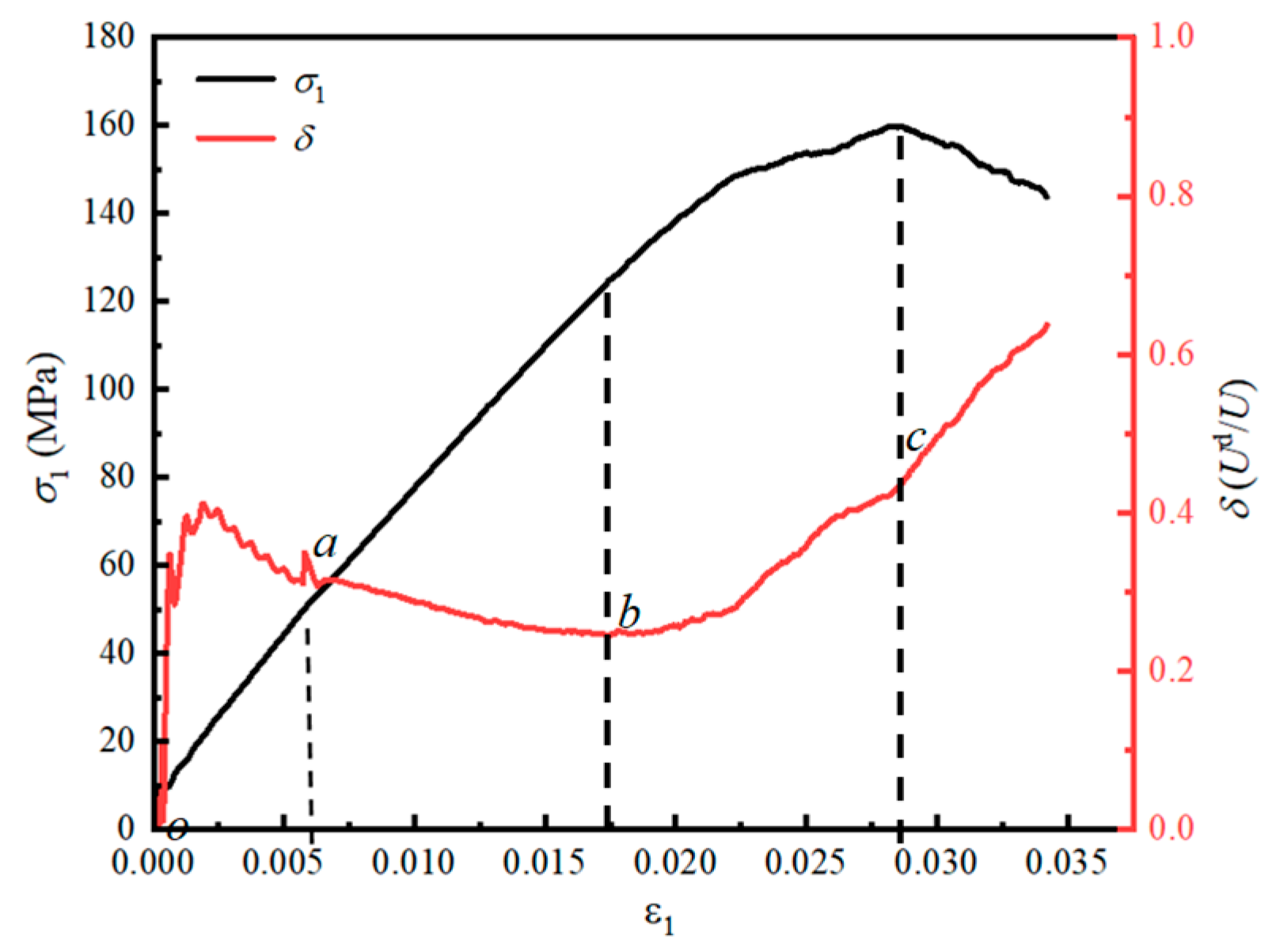

4.2. Energy Evolution Law of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Minimum Principal Stress Conditions

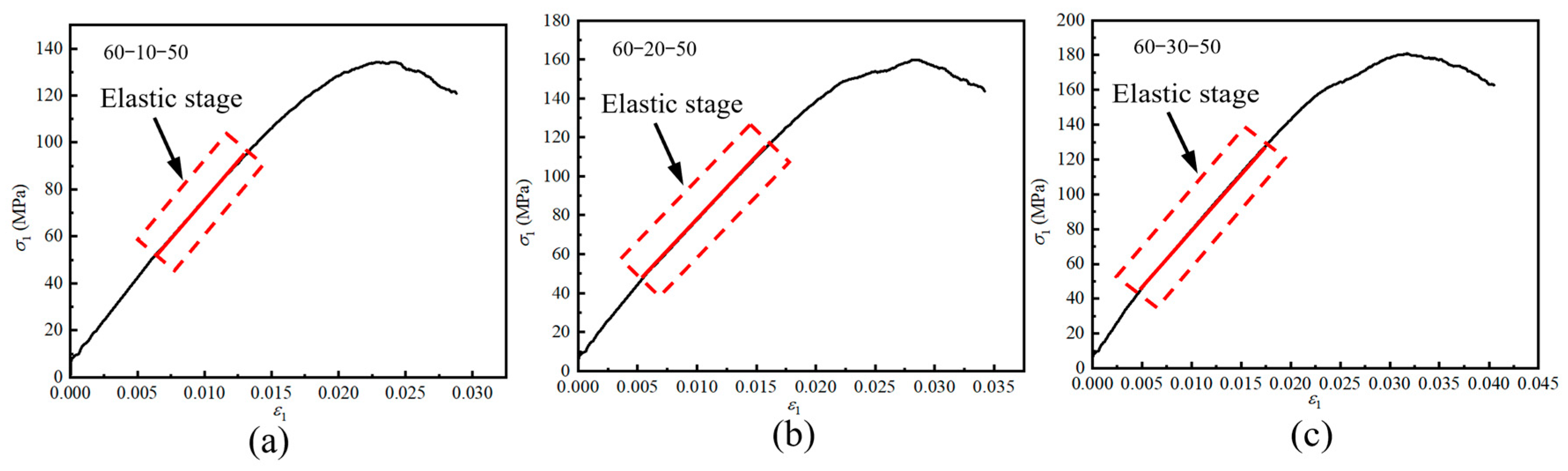

4.2.1. Energy Evolution of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Minimum Principal Stress Conditions

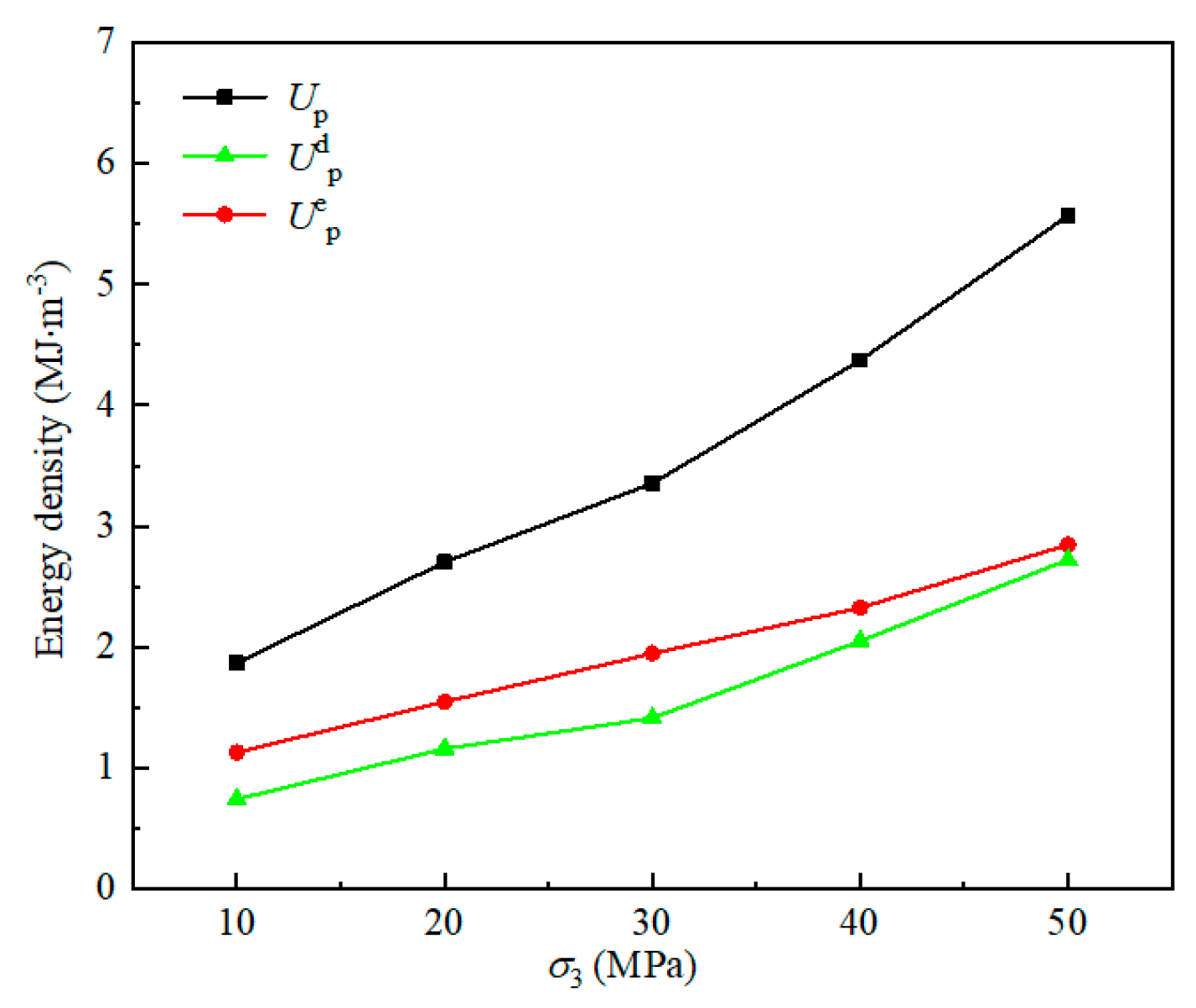

4.2.2. Variation Law of Energy at Peak Strength Under Different Minimum Principal Stress Conditions

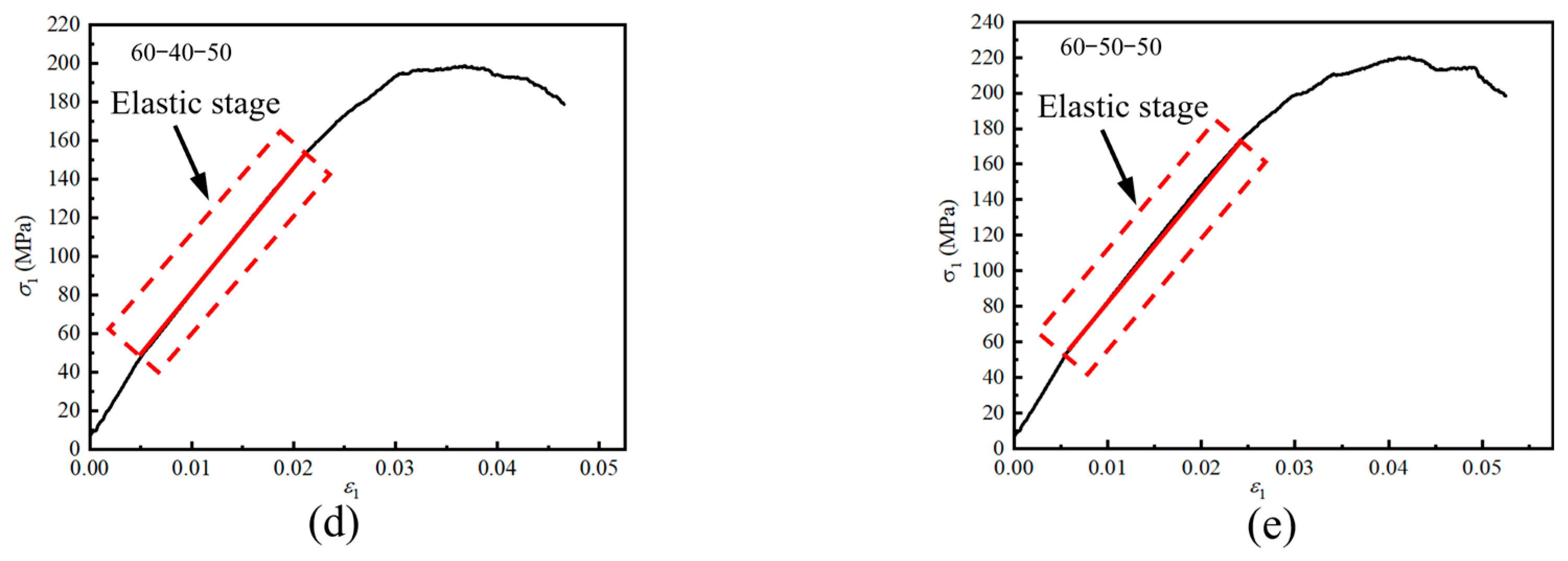

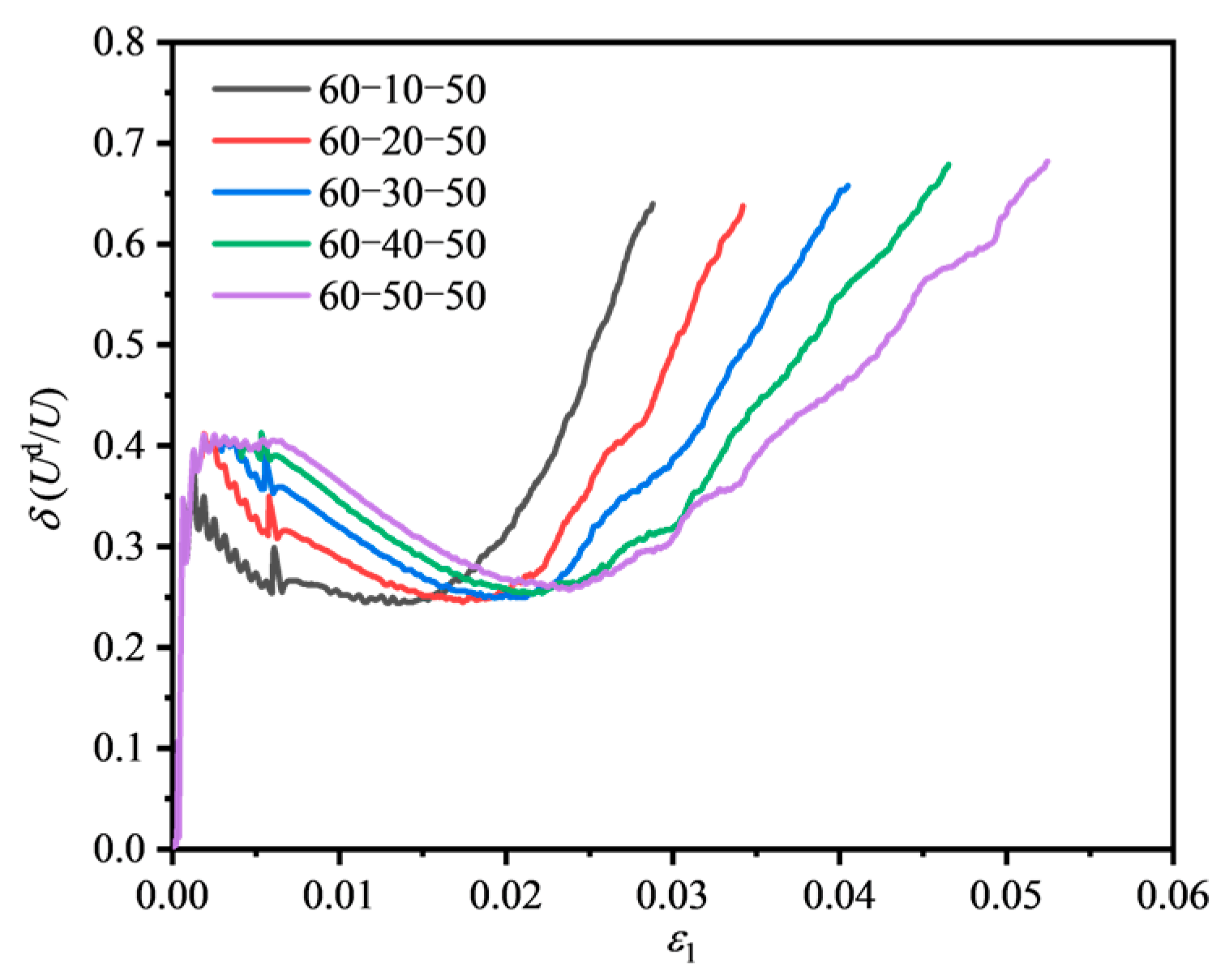

4.2.3. Variation of Dissipated Energy Ratio Under Different Minimum Principal Stress Conditions

4.3. Energy Evolution Law of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Intermediate Principal Stress Conditions

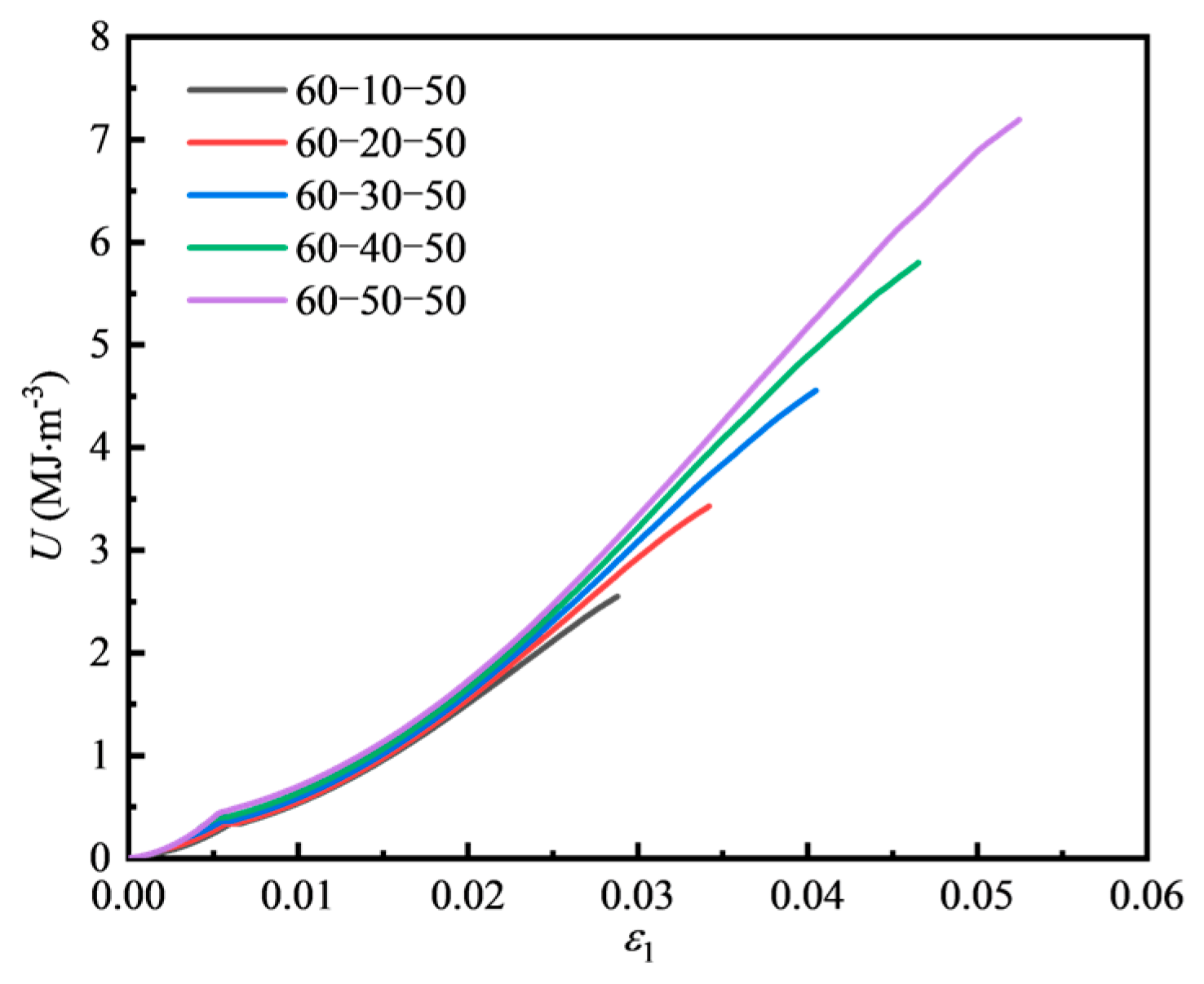

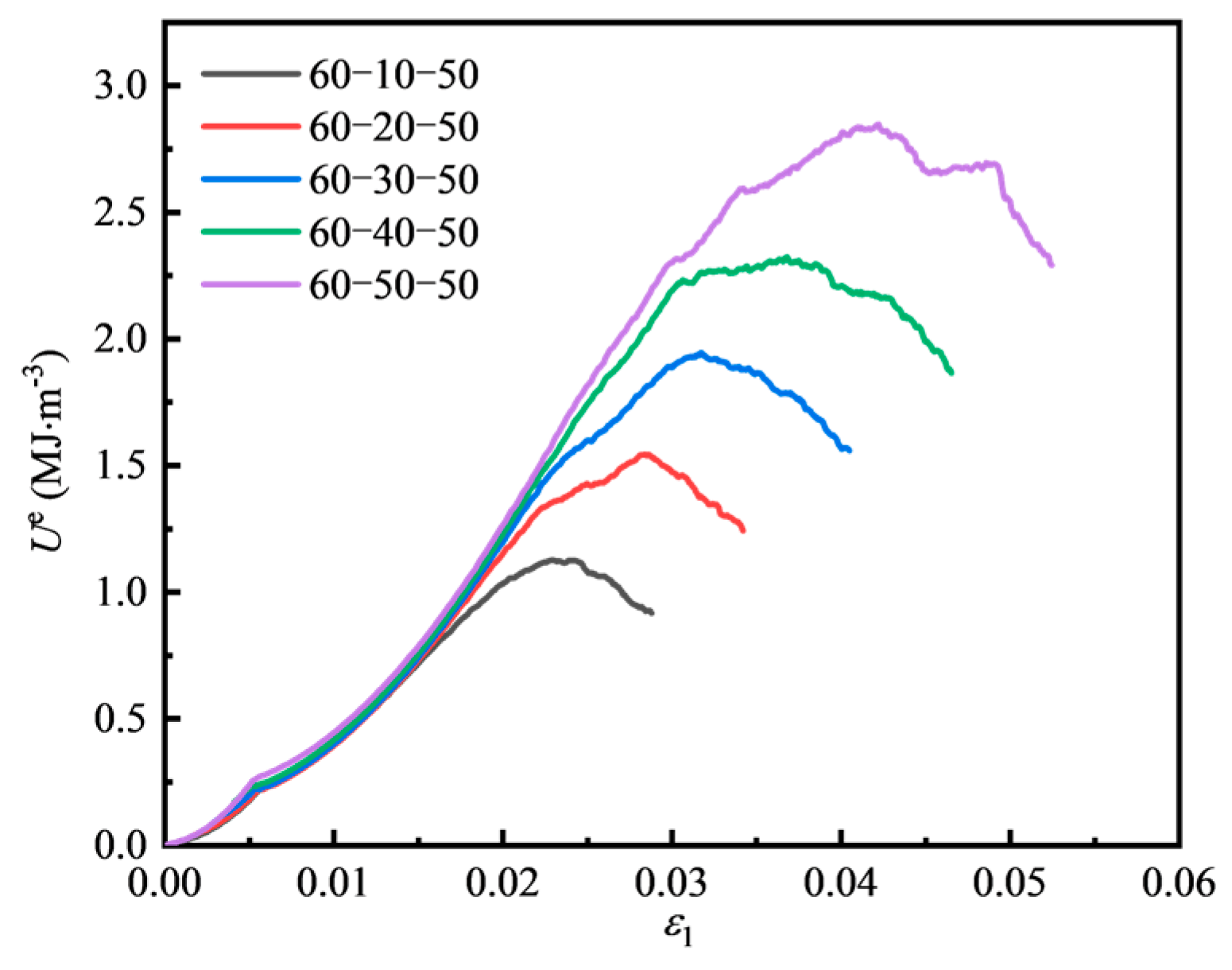

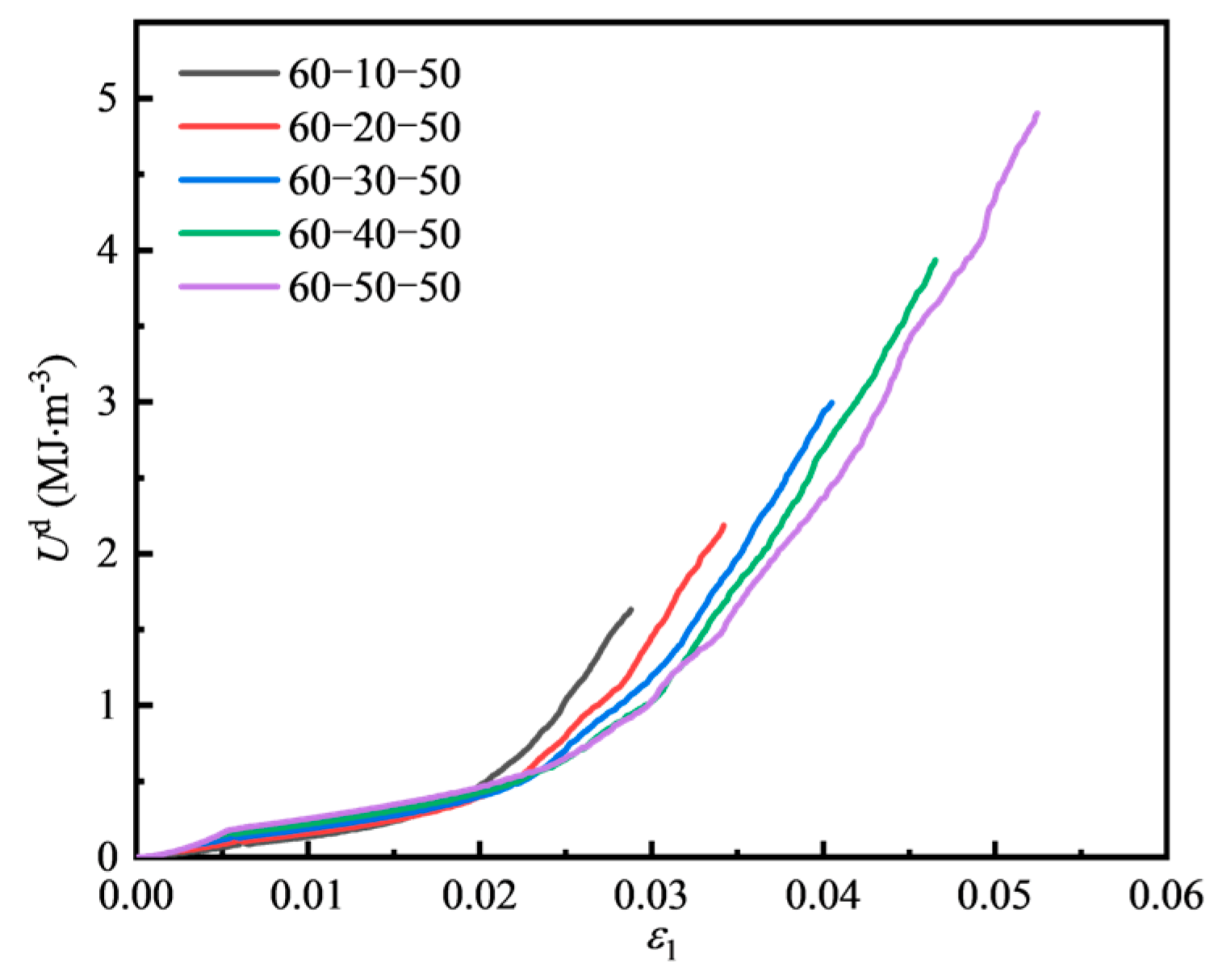

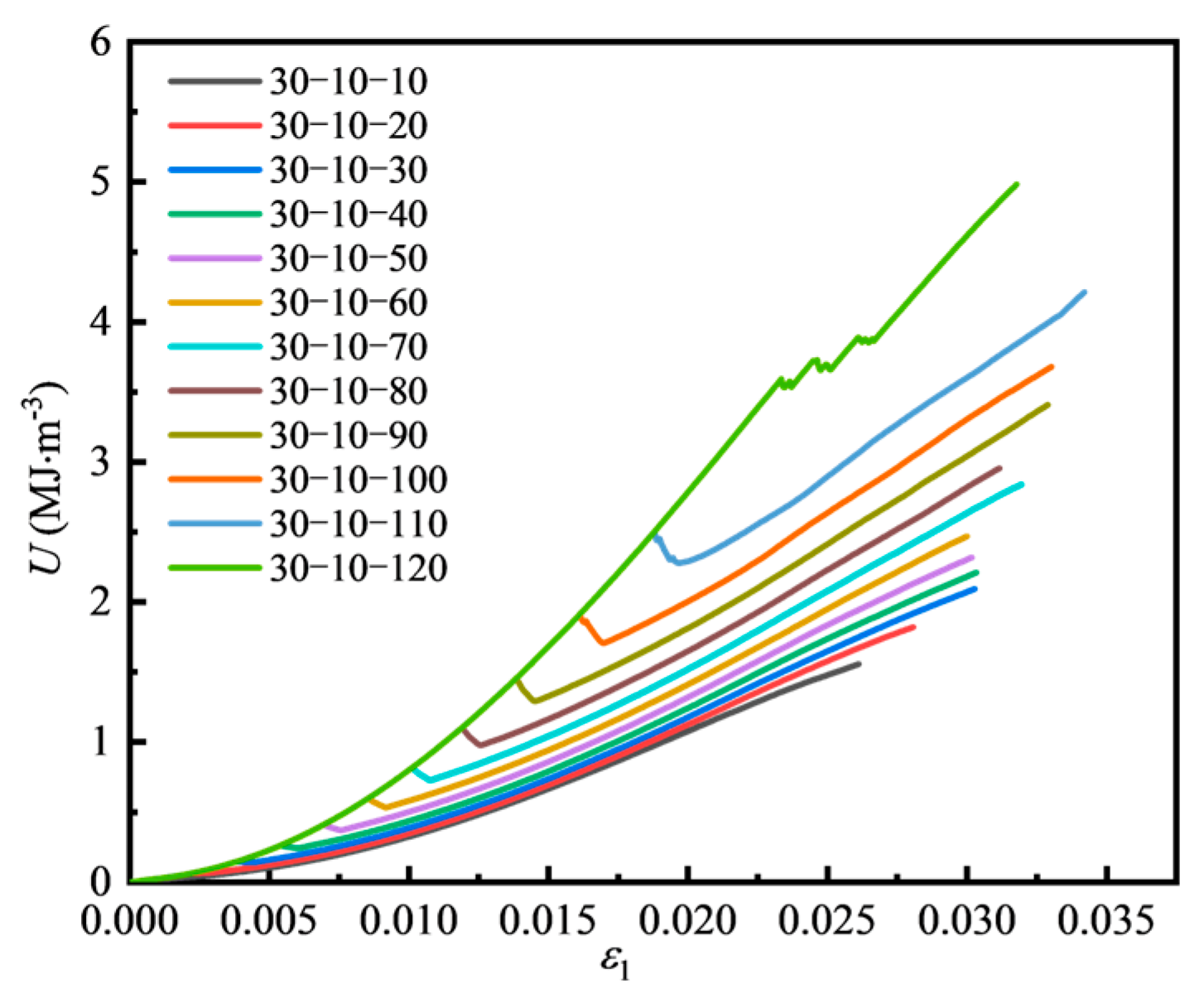

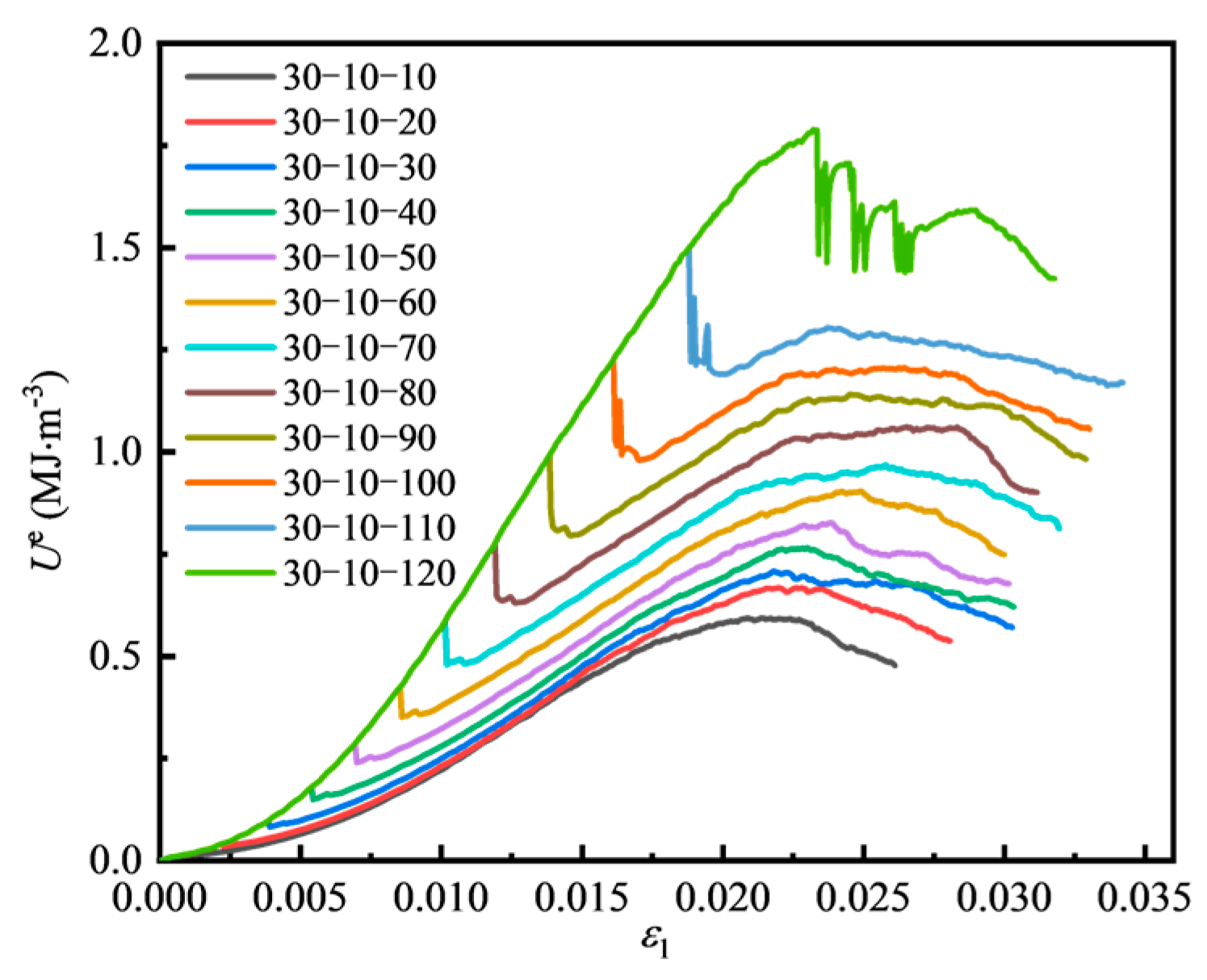

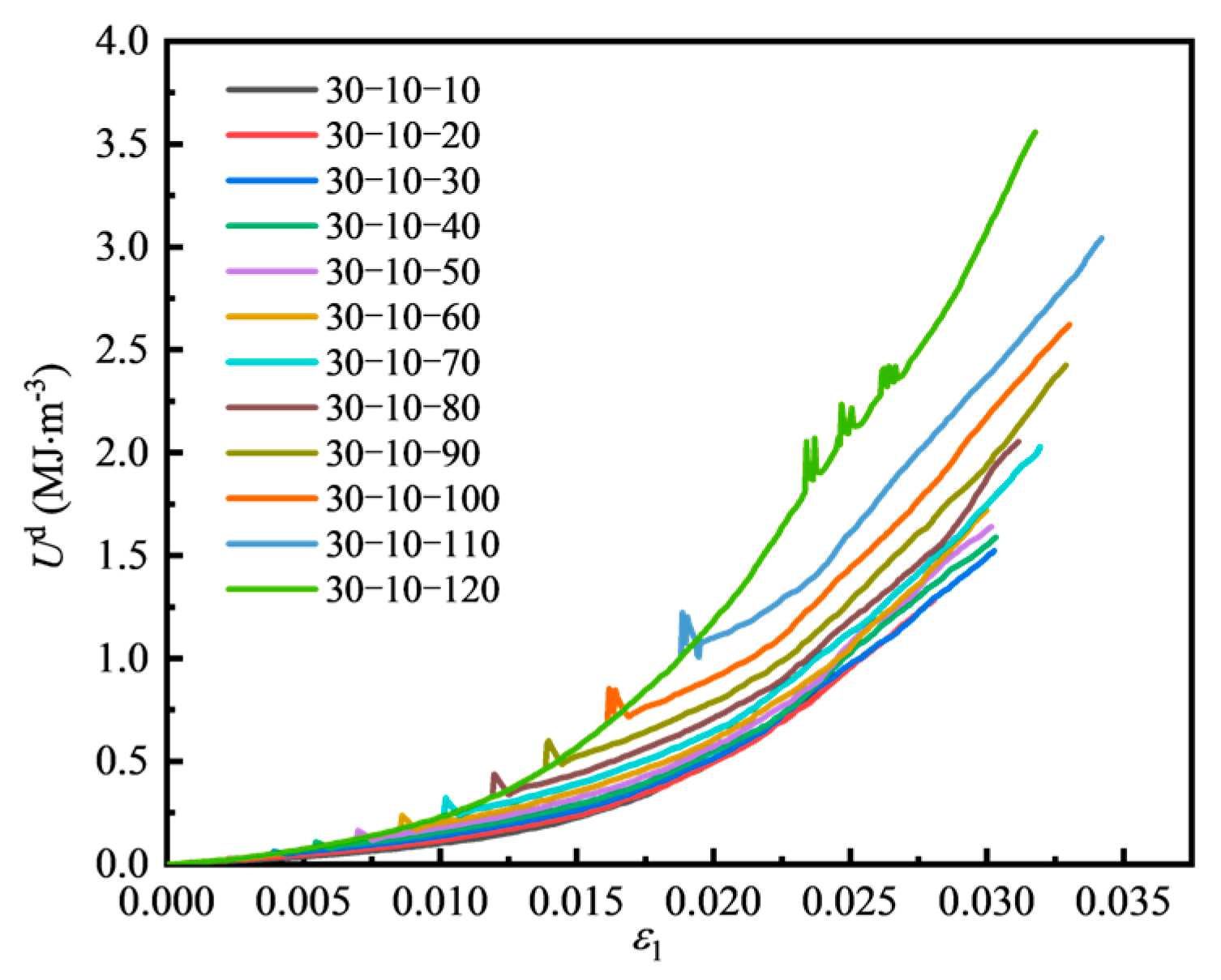

4.3.1. Energy Evolution of Fissured Sandstone Under Different Intermediate Principal Stress Conditions

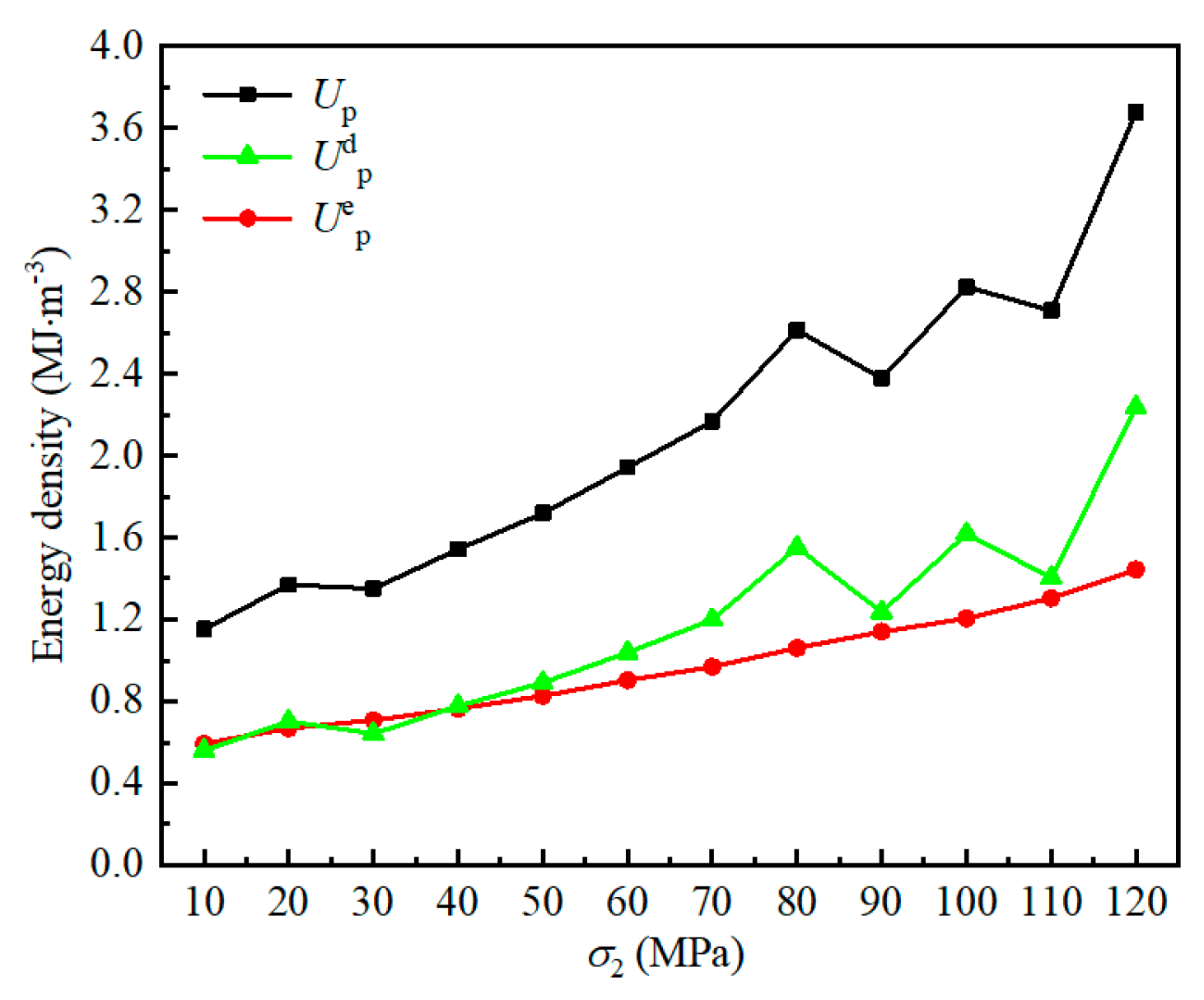

4.3.2. Energy Evolution at Peak Strength Under Different Intermediate Principal Stress Conditions

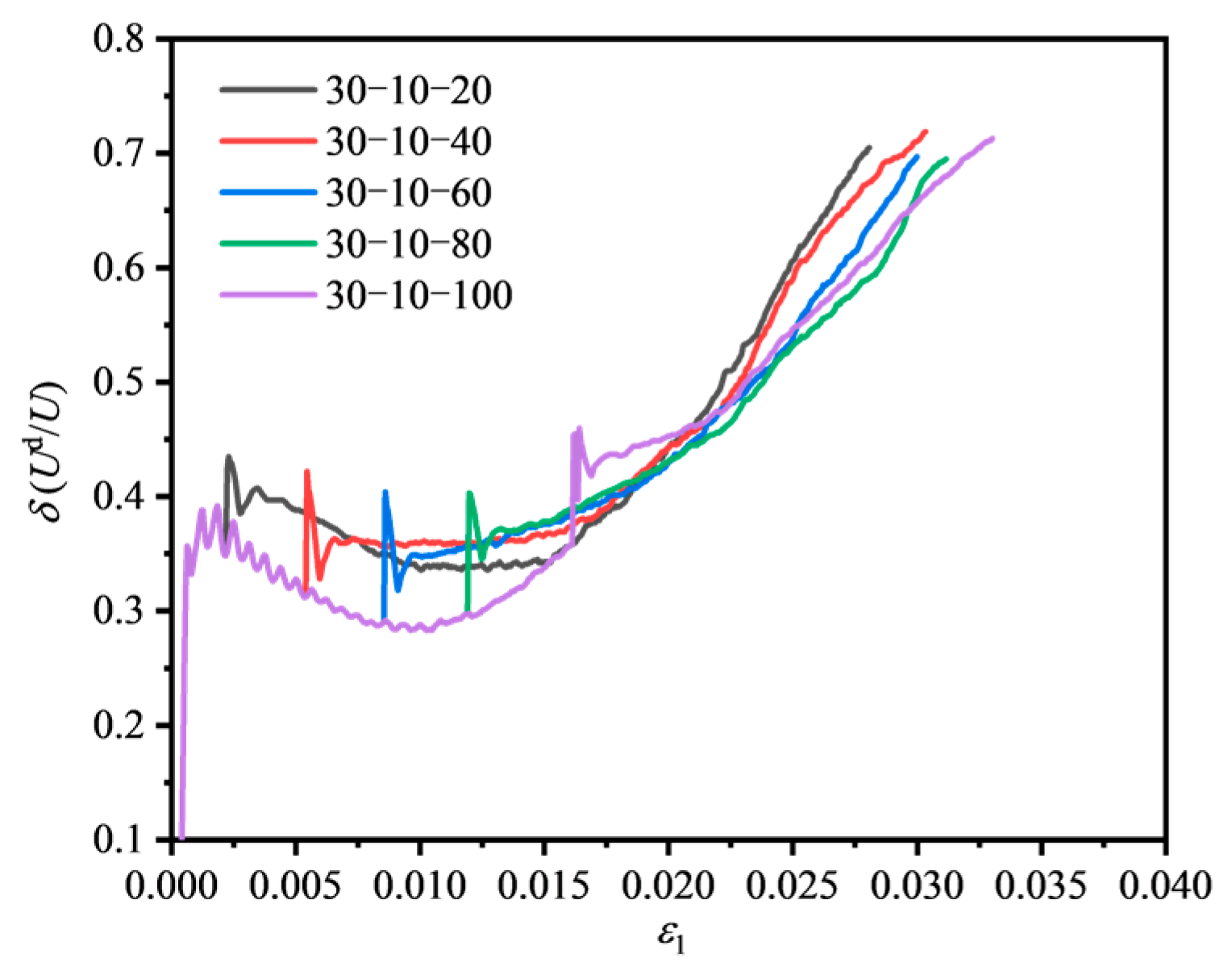

4.3.3. Variation in Dissipated Energy Ratio Under Different Intermediate Principal Stress Conditions

4.4. Energy Storage and Dissipation Analysis of Fissured Sandstone Under True Triaxial Compression

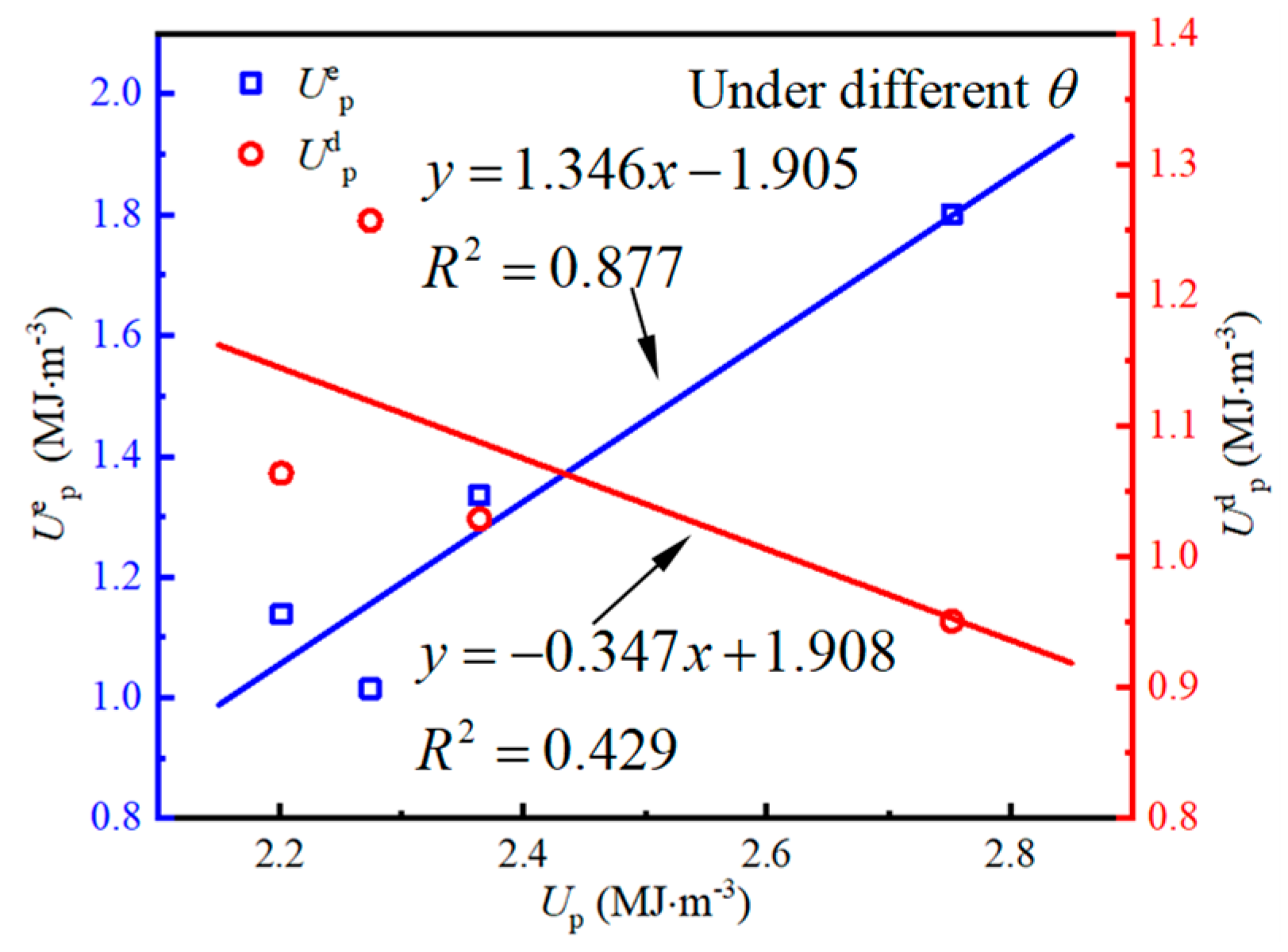

4.4.1. Differing Fissure Dip Angles

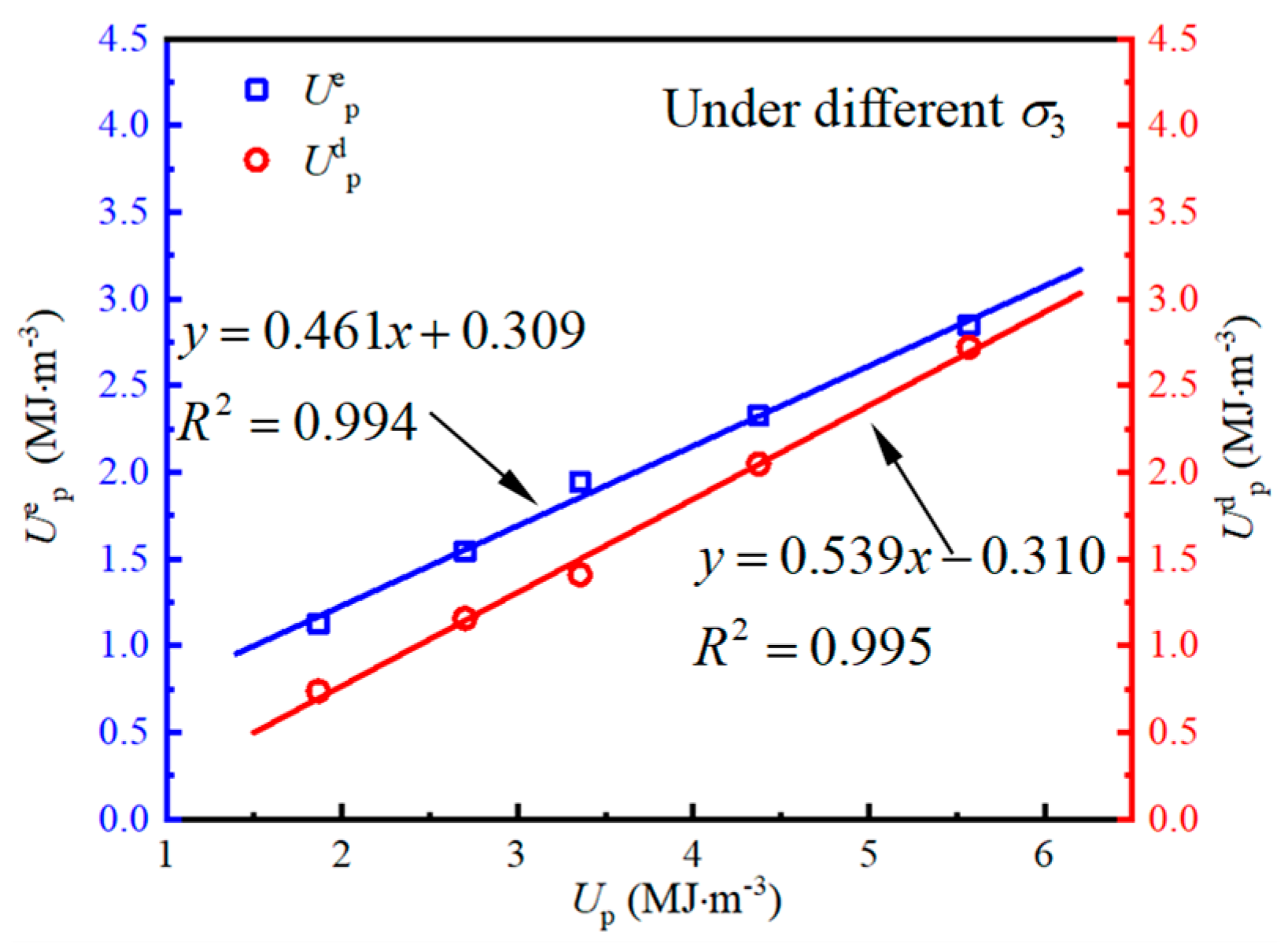

4.4.2. Differing Minimum Principal Stresses

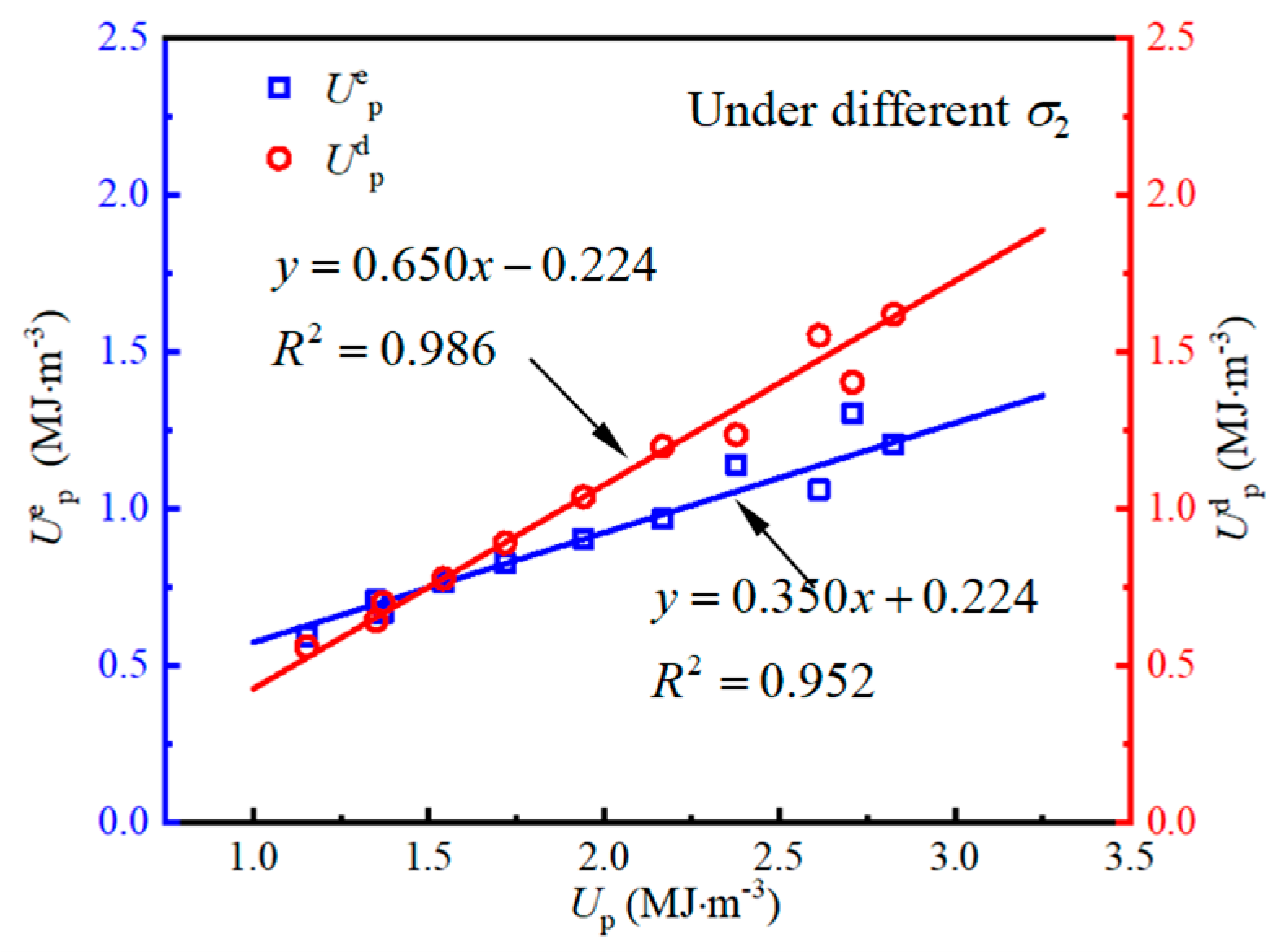

4.4.3. Differing Intermediate Principal Stresses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the initial loading stage and linear elastic stage, most of U in fissured sandstone is stored as Ue, with only a small part being dissipated. In the fluctuating stage, Ud increases faster, while Ue rises more slowly, though it still remains higher than dissipated energy. At the peak strength, Ue reaches its maximum. In the post-peak stage, Ud increases sharply, surpassing Ue, which begins to decline. The dissipated energy ratio first rises, then falls, and rises again as maximum principal strain increases. In the linear elastic stage, δ is low and almost unchanged.

- (2)

- As θ increases, both U and Ud increase with the rise in maximum principal strain, and Ue first increases and then decreases with increasing maximum principal strain. At peak strength, U first decreases and then increases with the increase in θ, while Ue gradually rises, and Ud gradually declines.

- (3)

- As σ3 increases, the curve slope of U changing with maximum principal strain gradually rises, indicating faster energy accumulation. The slope of Ue with maximum principal strain also increases. With the increase in σ3, Ud at the peak strength increases, as it promotes crack propagation and thus leads to greater energy dissipation.

- (4)

- With the increase in σ2, the curve slope of U with the maximum principal strain gradually increases, the curve becomes steeper, and energy accumulation becomes faster. With the increase in the maximum principal strain comes an increase in Ue with different values of σ2. With high σ2, Ud grows more rapidly, indicating faster damage accumulation in the rock mass. As σ2 increases, the Ue at peak strength of fissured sandstone specimens also rises, showing a nearly linear trend.

- (5)

- Under true triaxial compression, the linear correlation between Ue, Ud, and U at peak strength is weak with different values of θ, indicating nonlinear energy storage and dissipation behavior in fissured rock masses. Under different σ2 and σ3, linear correlation coefficients are high, showing a clear linear energy storage and dissipation law in fissured rock mass.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, B.; Kang, H.; Zuo, J.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Cai, M.; Liu, J. Study on damage anisotropy and energy evolution mechanism of jointed rock mass based on energy dissipation theory. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, B.; Cheng, L.; Lin, H.; Hu, B.; Liu, Z. Study on the Energy Evolution and Damage Mechanism of Fractured Rock Mass Under Stress–Seepage Coupling. Processes 2025, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Guo, L.J.; Zuo, J.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, G.F.; Hua, J.W. Discrete element simulations of fracture mechanism and energy evolution characteristics of typical rocks subjected to impact loads. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.P.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.L.; Yang, S.L.; Li, Q.S. Collaborative movement characteristics of overlying rock and loose layer based on block–particle discrete-element simulation method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, A.; Cui, D. Experimental Investigation on the Characteristic Stress and Energy Evolution Law of Carbonaceous Shale: Effects of Dry–Wet Cycles, Confining Pressure, and Fissure Angle. Processes 2025, 13, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.C.; Gong, F.Q.; Wu, W.X.; Wang, W.H. Experimental investigation of the mechanical behaviors and energy evolution characteristics of red sandstone specimens with holes under uniaxial compression. Bull Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 5845–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gao, W.; Hu, C.J.; Chen, X.; Cui, S. Numerical study of related factors affecting mechanical properties of fractured rock mass and its sensitivity analysis. Comput. Part. Mech. 2023, 10, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, W.; Shi, L.; Sun, G. Shear-Induced Anisotropy Analysis of Rock-like Specimens Containing Different Inclination Angles of Non-Persistent Joints. Mathematics 2025, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xu, F.; Bi, Y.; Bi, R.; Guo, Y.; Huo, N. Mechanical and Permeability Characteristics of Gas-Bearing Coal Under Various Bedding Angles. Processes 2025, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Xu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Mei, G. Generating Stochastic Structural Planes Using Statistical Models and Generative Deep Learning Models: A Comparative Investigation. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Qi, X.; Mei, G. A Deep Learning Approach for Stochastic Structural Plane Generation Based on Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. Mathematics 2022, 12, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gao, W.; He, T.Y.; Ge, S.S.; Ma, P.F.; Zhou, C. Study on constitutive model of fractured rock masses by using statistical strength theory. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2025, 48, 8274–8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y. Energy Dissipation of Rock with Different Parallel Flaw Inclinations under Dynamic and Static Combined Loading. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Chen, S.J.; Zhao, X.D.; Li, D.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Cui, J.Q. Effects of external dynamic disturbances and structural plane on rock fracturing around deep underground cavern. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Li, X.B.; Rostami, J.; Li, D.Y. Modeling hard rock failure induced by structural planes around deep circular tunnels. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2019, 205, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.S.; Chen, L.X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.X. Experimental investigation on mechanical, acoustic, and fracture behaviors and the energy evolution of sandstone containing non-penetrating horizontal fissures. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 123, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Yao, Z.S.; Huang, X.W.; Liu, X.H.; Fang, Y.; Xu, Y.J. Mechanical properties and energy evolution of fractured sandstone under cyclic loading. Materials 2022, 15, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.W.; Li, Y.; Hu, H.R.; Luo, Y.F.; Peng, J.J. Effect of Crack Angle on Mechanical Behaviors and Damage Evolution Characteristics of Sandstone Under Uniaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 6567–6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.L.; Cao, T.C.; Sun, F.; Wen, X.X.; Zhang, L. Study on the meso-energy damage evolution mechanism of single-joint sandstone under uniaxial and biaxial compression. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 5245402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Xie, Z.W.; Chen, S.J.; Li, D.Y.; Peng, S.Y.; Zhang, T. True triaxial unloading test on the mechanical behaviors of sandstone: Effects of the intermediate principal stress and structural plane. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 2208–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.J.; Peng, S.Y.; Xie, Z.W.; Zhao, Y.M. Analysis of failure properties of red sandstone with structural plane subjected to true triaxial stress paths. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 310, 110490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.D.; Wang, Z.Q.; Jiang, Z.S.; Xie, S.R.; Li, Z.J.; Ye, Q.C.; Zhu, J.K. Research on J2 evolution law and control under the condition of internal pressure relief in surrounding rock of deep roadway. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.Q.; Zhu, C.; Karakus, M.; He, M.C. Rockburst mitigation mechanisms of pressure relief borehole and rock bolt support: Insights from granite true triaxial unloading rockburst tests. Eng. Geol. 2024, 336, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.W.; Fan, Y.Y.; Su, W.W.; Wang, J.C.; Lan, M.; Lin, Q.B. Optimization of support and relief parameters for deep-buried metal mine roadways. Geofluids 2024, 8816030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, P.F.; Xu, C.B.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.Y. Failure characteristics and pressure relief effectiveness of non-persistent jointed rock mass with holes. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 134, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.Y.; Zuo, Y.J.; Chen, Q.G.; Zheng, L.J.; Rong, P.; Liu, H.; Jin, K.Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Chen, B.; Xing, B. Study on the response characteristics of roadway borehole pressure relief surrounding rock under strike-slip high-stress distribution. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 156, 107808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.T.; Zhang, X.W.; Kong, R.; Wang, G. A novel mogi type true triaxial testing apparatus and its use to obtain complete stress-strain curves of hard rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.P.; Peng, R.D.; Ju, Y. Energy dissipation of rock deformation and fracture. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2004, 23, 3565–3570. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.P.; Ju, Y.; Li, L.Y.; Peng, R.D. Energy mechanism of deformation and failureof rock masses. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2008, 27, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Huang, R.Q.; Zhang, Y.X. Experimental investigations on static loading rate effects on mechanical properties and energy mechanismof coarse crystal grain marble under uniaxialcompression. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.M.; Gao, S.; Wang, Z.Q.; Cong, Y. Analysis of marble failure energy evolution under loading and unloading conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2013, 32, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Zhang, T.; Rostami, J.; Chen, S.J.; Zhao, X.D.; Qiu, J.D. Crack propagation and strength characteristic of sandstone with structural defects under extensive true triaxial tests by using DEM simulation. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 138, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.Q.; Yan, J.Y.; Li, X.B.; Luo, S. A peak-strength strain energy storage index for rock burst proneness of rock materials. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 117, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.Q.; Yan, J.Y.; Luo, S.; Li, X.B. Investigation on the linear energy storage and dissipation laws of rock materials under uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 4237–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Gong, F.Q.; Luo, S. Effects of pre-existing single crack angle on mechanical behaviors and energy storage characteristics of red sandstone under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 113, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Q.; Gong, F.Q.; Luo, S.; Liu, Z.X. Experimental study on energy storage and dissipation characteristics of granite under two-dimensional compression with constant confining pressure. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 848–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Gong, F.Q.; Li, L.L.; Peng, K. Linear energy storage and dissipation laws and damage evolution characteristics of rock under triaxial cyclic compression with different confining pressures. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 2168–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.D.; Huang, R.; Wang, H.W.; Wang, F.; Zhou, C.T. Rate-dependent tensile behaviors of jointed rock masses considering geological conditions using a combined BPM-DFN model: Strength, fragmentation and failure modes. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng 2025, 195, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.T.; Rui, Y.C.; Qiu, J.D.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhou, T.; Long, X.T.; Shan, K. The role of fracture in dynamic tensile responses of fractured rock mass: Insight from a particle-based model. Int. J. Coal. Sci. Techn 2025, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen Number | θ (°) | σ3 (MPa) | σ2 (MPa) | σ1,peak (MPa) | Up (MJ/m3) | Uep (MJ/m3) | Udp (MJ/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-20-30 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 134.263 | 2.274 | 1.017 | 1.257 |

| 45-20-30 | 45 | 20 | 30 | 159.904 | 2.201 | 1.138 | 1.064 |

| 60-20-30 | 60 | 20 | 30 | 181.029 | 2.364 | 1.335 | 1.029 |

| 90-20-30 | 90 | 20 | 30 | 198.727 | 2.752 | 1.801 | 0.951 |

| 60-10-50 | 60 | 10 | 50 | 220.215 | 1.866 | 1.127 | 0.738 |

| 60-20-50 | 60 | 20 | 50 | 97.058 | 2.701 | 1.544 | 1.157 |

| 60-30-50 | 60 | 30 | 50 | 104.108 | 3.355 | 1.945 | 1.410 |

| 60-40-50 | 60 | 40 | 50 | 107.495 | 4.372 | 2.324 | 2.048 |

| 60-50-50 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 111.281 | 5.569 | 2.847 | 2.722 |

| 30-10-10 | 30 | 10 | 10 | 114.355 | 1.153 | 0.594 | 0.560 |

| 30-10-20 | 30 | 10 | 20 | 117.667 | 1.370 | 0.668 | 0.702 |

| 30-10-30 | 30 | 10 | 30 | 119.048 | 1.351 | 0.708 | 0.643 |

| 30-10-40 | 30 | 10 | 40 | 121.804 | 1.543 | 0.765 | 0.778 |

| 30-10-50 | 30 | 10 | 50 | 122.308 | 1.718 | 0.827 | 0.891 |

| 30-10-60 | 30 | 10 | 60 | 120.863 | 1.942 | 0.904 | 1.038 |

| 30-10-70 | 30 | 10 | 70 | 120.620 | 2.167 | 0.968 | 1.199 |

| 30-10-80 | 30 | 10 | 80 | 120.173 | 2.613 | 1.061 | 1.552 |

| 30-10-90 | 30 | 10 | 90 | 130.383 | 2.377 | 1.140 | 1.236 |

| 30-10-100 | 30 | 10 | 100 | 137.548 | 2.825 | 1.206 | 1.619 |

| 30-10-110 | 30 | 10 | 110 | 148.484 | 2.708 | 1.304 | 1.404 |

| 30-10-120 | 30 | 10 | 120 | 171.347 | 3.678 | 1.443 | 2.235 |

| Influencing Factor | Energy Type | Slope | Intercept | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ3 | Uep | 0.461 | 0.309 | 0.994 |

| Udp | 0.539 | −0.310 | 0.995 | |

| σ2 | Uep | 0.350 | 0.224 | 0.952 |

| Udp | 0.650 | −0.224 | 0.986 | |

| θ | Uep | 1.346 | −1.905 | 0.877 |

| Udp | −0.347 | 1.908 | 0.429 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, F.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S. Energy Evolution of Far-Field Surrounding Rock Under True Triaxial Compression Conditions: Taking Fissured Sandstone as an Example. Processes 2026, 14, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020356

Feng F, Li Y, Li C, Qiu J, Zhang T, Chen S. Energy Evolution of Far-Field Surrounding Rock Under True Triaxial Compression Conditions: Taking Fissured Sandstone as an Example. Processes. 2026; 14(2):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020356

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Fan, Yuanpu Li, Chenglin Li, Jiadong Qiu, Tong Zhang, and Shaojie Chen. 2026. "Energy Evolution of Far-Field Surrounding Rock Under True Triaxial Compression Conditions: Taking Fissured Sandstone as an Example" Processes 14, no. 2: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020356

APA StyleFeng, F., Li, Y., Li, C., Qiu, J., Zhang, T., & Chen, S. (2026). Energy Evolution of Far-Field Surrounding Rock Under True Triaxial Compression Conditions: Taking Fissured Sandstone as an Example. Processes, 14(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020356