Acoustic–Electric Conversion Characteristics of a Quadruple Parallel-Cavity Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator (4C–HR TENG)

Abstract

1. Introduction

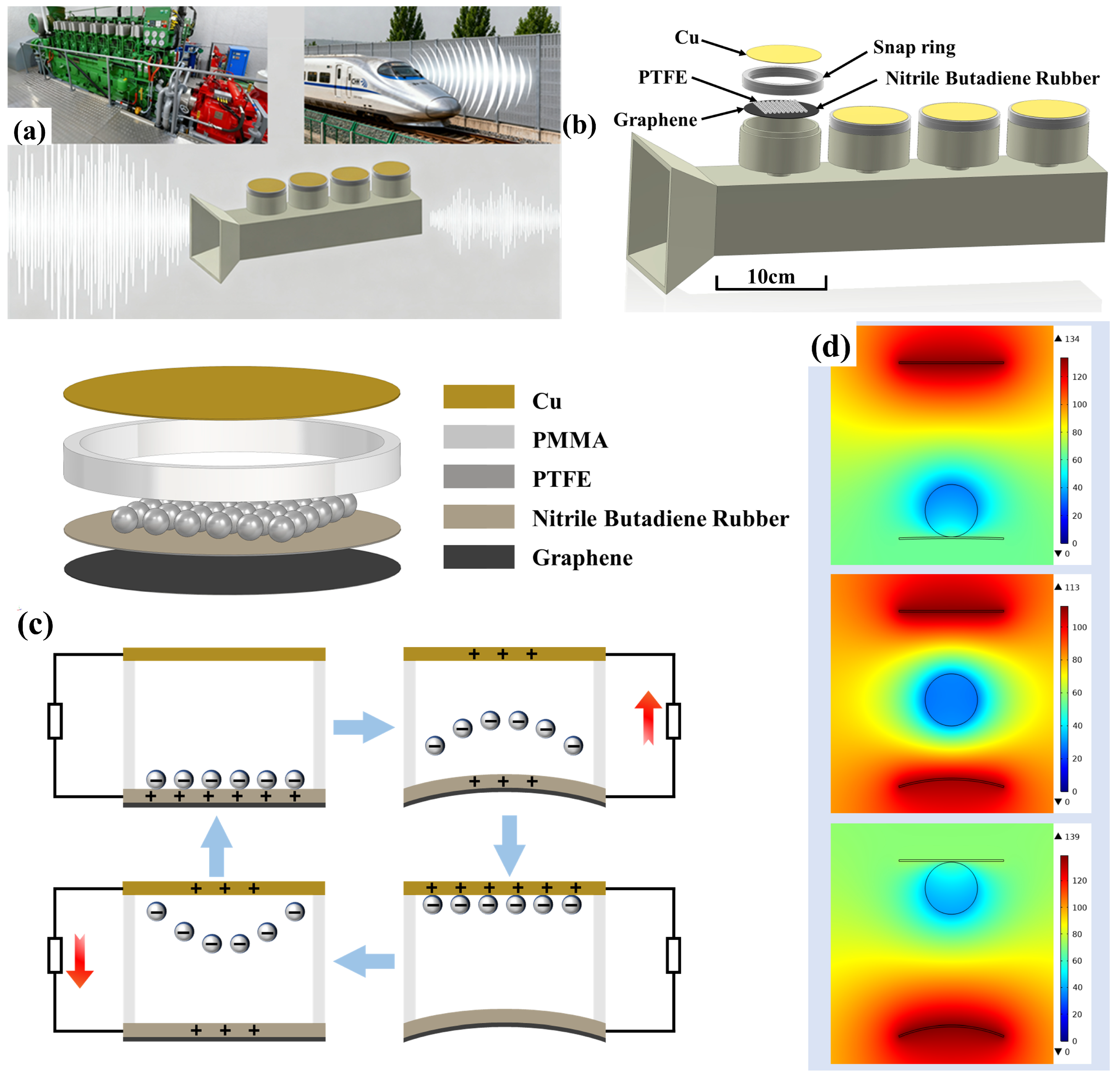

2. Working Principle and Simulation Analysis

2.1. Theoretical Analysis and Output Performance Simulation

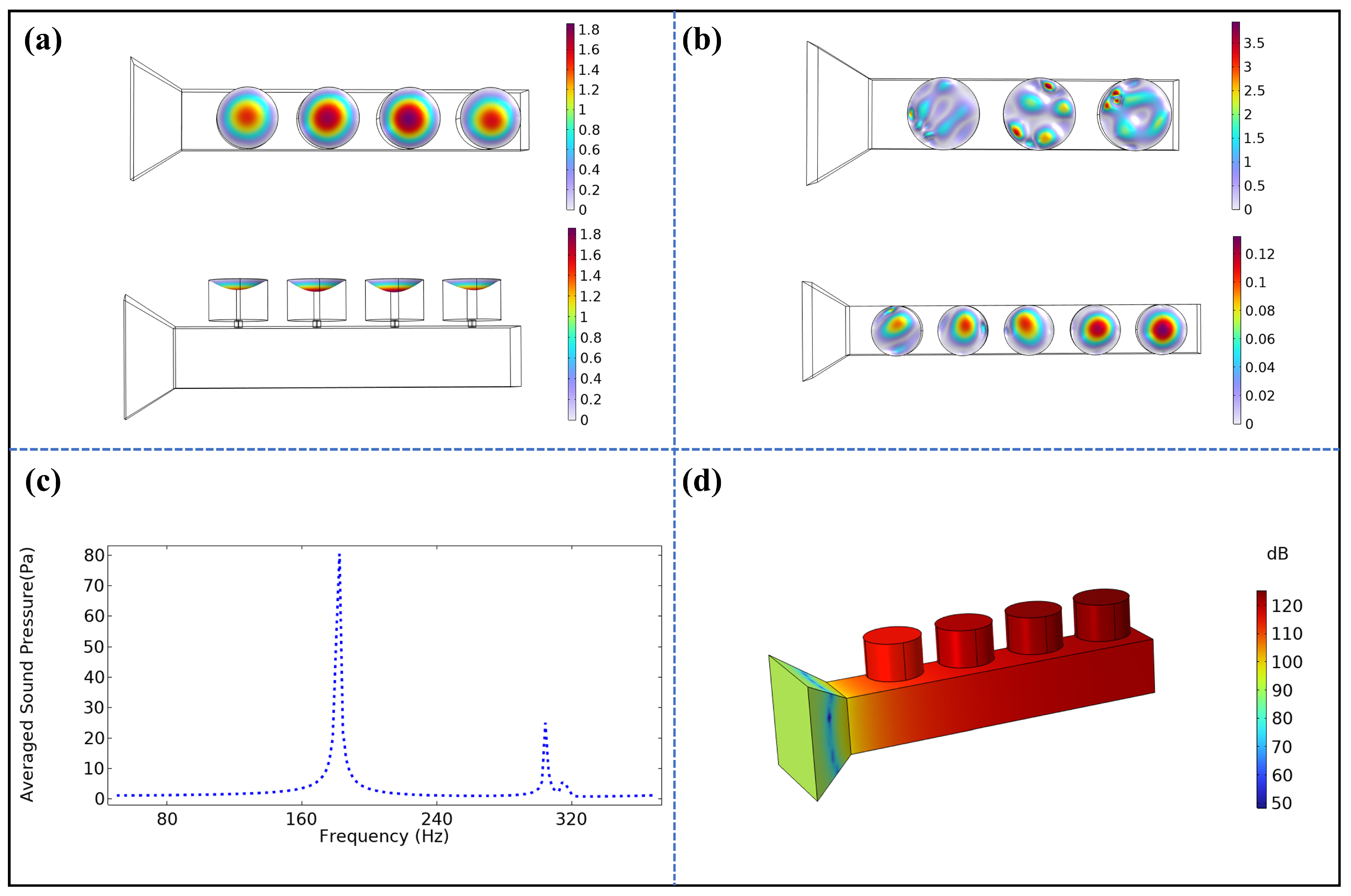

2.2. Model Analysis

2.3. Simulation Analysis of Diaphragm Displacement Characteristics and Acoustic Performance

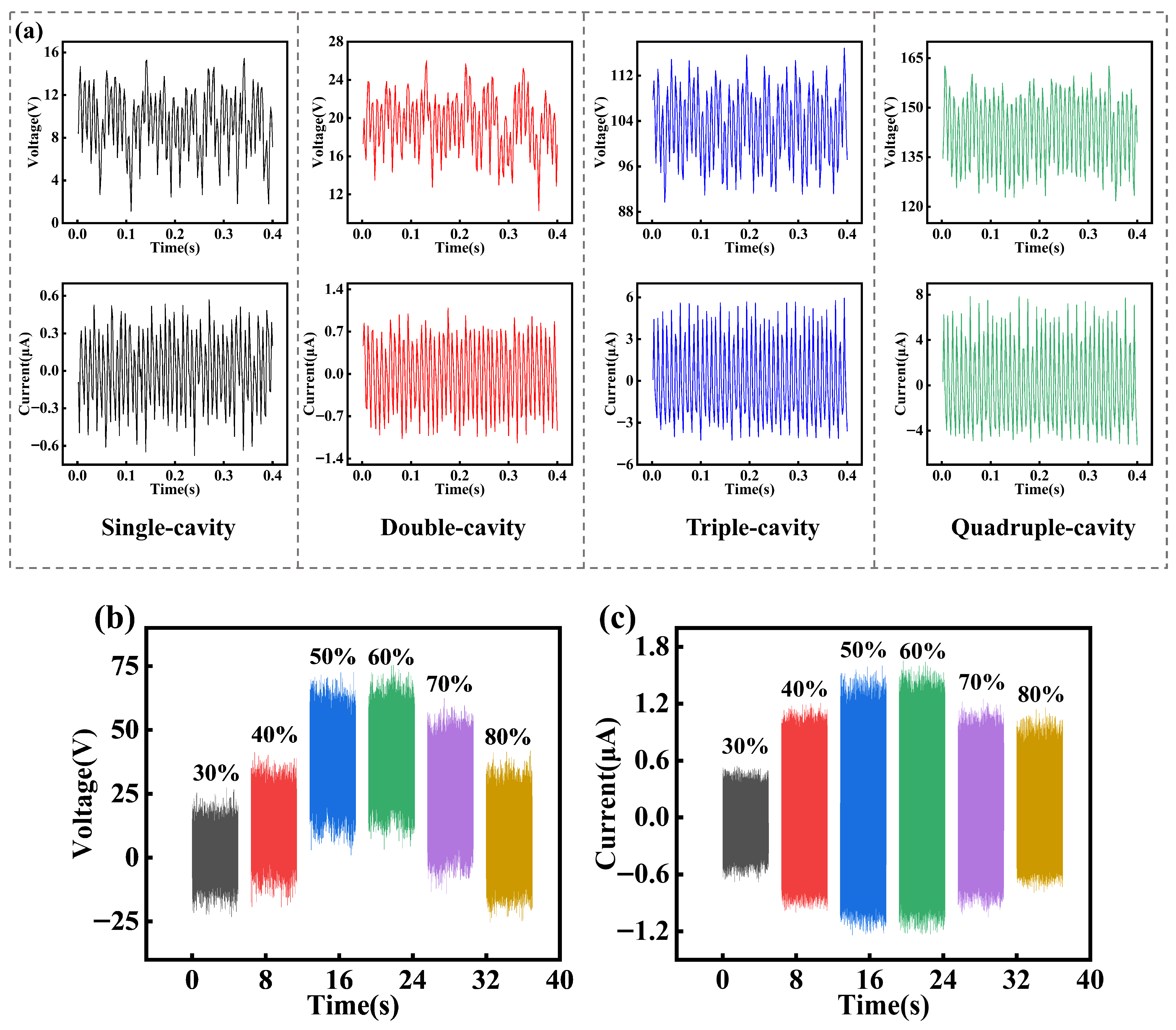

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Filling Ratio

3.2. Height Between the Electrode Plates

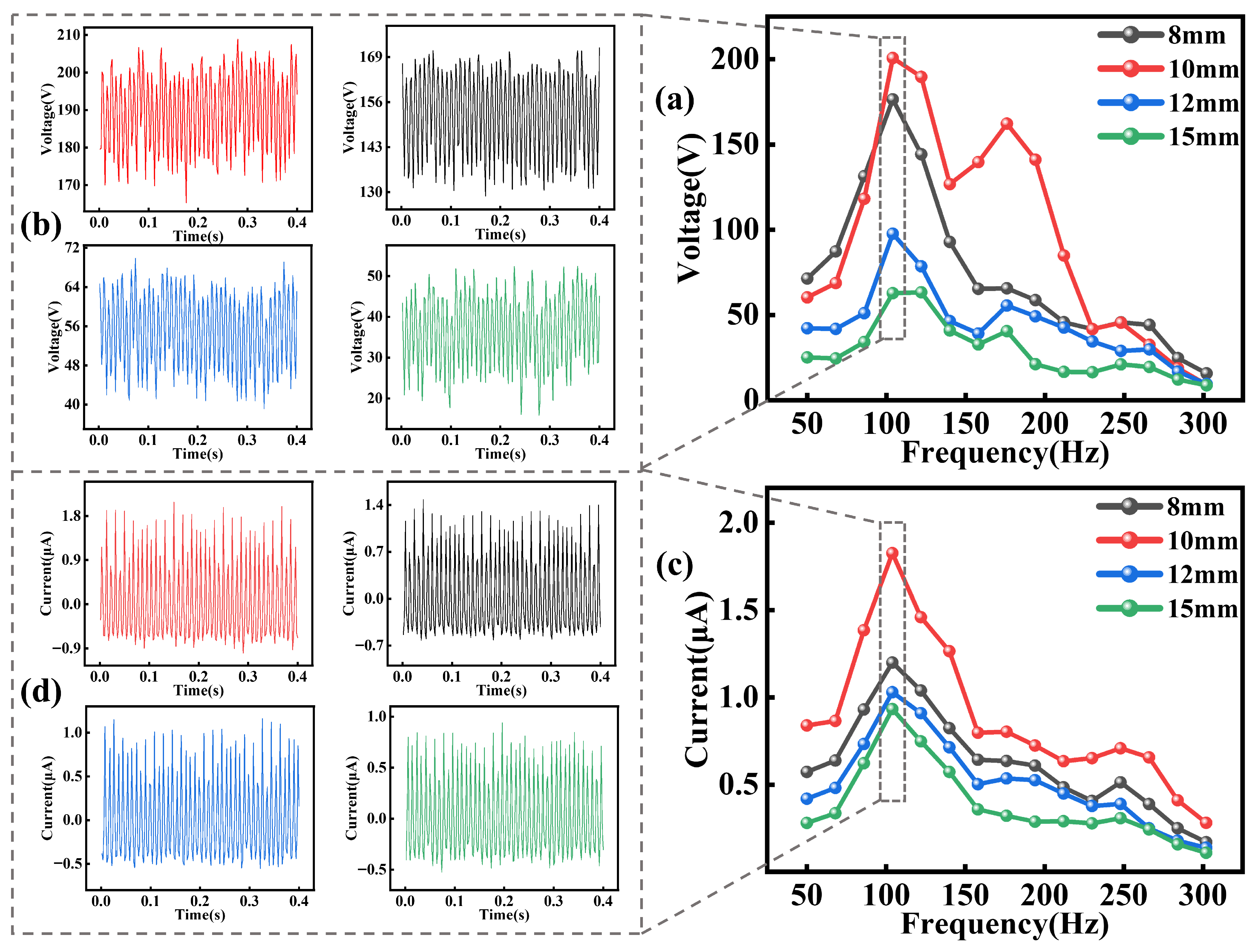

3.3. Influence of Particle Size on the Power Generation Characteristics of the 4C–HR TENG

3.4. Acoustic Source Characteristics of 4C–HR TENG

3.5. Material of the Upper Electrode Plate

3.6. Applications

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Fabrication of the 4C–HR TENG

4.2. Relevant Equipment for the Acoustic–Electric Conversion Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Du, T.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Si, J.; Yu, H.; Yuan, H.; Sun, P.; Xu, M. Research Progress of Acoustic Energy Harvesters Based on Nanogenerators. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 5568046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Lin, L.; Niu, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Self-Powered Trajectory, Velocity, and Acceleration Tracking of a Moving Object/Body using a Triboelectric Sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 7488–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Tee, B.C.K.; Chortos, A.L.; Schwartz, G.; Tse, V.; Lipomi, D.J.; Wong, H.-S.P.; McConnell, M.V.; Bao, Z. Continuous wireless pressure monitoring and mapping with ultra-small passive sensors for health monitoring and critical care. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ouyang, B.; Bowen, C.R.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, Y. One-structure-based multi-effects coupled nanogenerators for flexible and self-powered multi-functional coupled sensor systems. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, F.; Khan, M.U.; Alazzam, A.; Mohammad, B. Harnessing ambient sound: Different approaches to acoustic energy harvesting using triboelectric nanogenerators. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2024, 9, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, K.; Wei, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Enabled Body Sensor Network for Self-Powered Human Heart-Rate Monitoring. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8830–8837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG)—Sparking an Energy and Sensor Revolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2000137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. On the first principle theory of nanogenerators from Maxwell’s equations. Nano Energy 2020, 68, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, V.-L.; Chung, C.-K. Use of Triboelectric Nanogenerators in Advanced Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for High Efficiency in Sustainable Energy Production: A Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, J.; Zi, Y.; Li, X.; Han, C.; Cao, X.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z. High efficient harvesting of underwater ultrasonic wave energy by triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2017, 38, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Guo, L.; Xue, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; He, X.; Dai, G.; Jiang, P.; et al. Quantifying and understanding the triboelectric series of inorganic non-metallic materials. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zuo, X.; Dong, F.; Li, S.; Mtui, A.E.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; et al. A Self-Powered and Highly Accurate Vibration Sensor Based on Bouncing-Ball Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Intelligent Ship Machinery Monitoring. Micromachines 2021, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Qi, Y.; Bu, T.; Li, X.; Liu, G.; Zeng, J.; Fan, B.; Zhang, C. Overview of Advanced Micro-Nano Manufacturing Technologies for Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Nanoenergy Adv. 2022, 2, 316–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, W.; Bamgboje, D.; Guo, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, Z.L. Self-driven power management system for triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Khattak, M.U. Contributed Review: Recent developments in acoustic energy harvesting for autonomous wireless sensor nodes applications. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 021501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.L.; Fernández, F.M. Large-Area Triboelectric Nanogenerator Mass Spectrometry: Expanded Coverage, Double-Bond Pinpointing, and Supercharging. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 31, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Xiong, L. The effect of the electric field on the output performance of triboelectric nanogenerators. J. Comput. Electron. 2020, 19, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jung, I.; Kang, C.-Y. A brief review of sound energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, G.; Yang, W.; Jing, Q.; Bai, P.; Yang, Y.; Hou, T.; Wang, Z.L. Harmonic-Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator as a Sustainable Power Source and a Self-Powered Active Vibration Sensor. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6094–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Lin, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. A high-performance coniform Helmholtz Resonator-based triboelectric nanogenerator for acoustic energy harvesting. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Gupta, S.; Katru, R.; Madathil, N.; Kulandaivel, A.; Kodali, P.; Divi, H.; Borkar, H.; Khanapuram, U.K.; Rajaboina, R.K. From Acoustic to Electric: Advanced Triboelectric Nanogenerators with Fe-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2400796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, L.; Xi, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, M. Research on an Optimized Quarter-Wavelength Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Efficient Low-Frequency Acoustic Energy Harvesting. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Madathil, N.; Rajaboina, R.K.; Borkar, H.; Devarayapalli, K.C.; Mishra, Y.K.; Hajra, S.; Kim, H.J.; Khanapuram, U.K.; Lee, D.S. Functionalized MIL-125(Ti)-based high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators for hygiene monitoring. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 4725–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Wen, Z. Advances in triboelectric nanogenerators in acoustics: Energy harvesting and Sound sensing. Nano Trends 2024, 8, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xiao, X.; Xu, P.; Zhao, T.; Song, L.; Pan, X.; Mi, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.L. Dual-Tube Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Highly Efficient Harvesting of Acoustic Energy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1902824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectrification-based organic film nanogenerator for acoustic energy harvesting and self-powered active acoustic sensing. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanapurarm, U.K.; Rani, G.M.; Panda, S.; Charoonsuk, T.; Mistewicz, K.; Hajra, S.; Kaja, K.R.; Umapathi, R.; Sriphan, S.; Jała, J.; et al. Harvesting Energy from Friction: The Revolutionary Decade of Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Powder Mater. 2025, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology for self-powered systems and as active mechanical and chemical sensors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9533–9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, A.C.; Ding, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator: A Foundation of the Energy for the New Era. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1802906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yuan, M. Acoustic Metamaterial Nanogenerator for Multi-Band Sound Insulation and Acoustic–Electric Conversion. Sensors 2025, 25, 6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Huang, C.; Wang, Z. Acoustic–Electric Conversion Characteristics of a Quadruple Parallel-Cavity Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator (4C–HR TENG). Processes 2026, 14, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020341

Li X, Huang C, Wang Z. Acoustic–Electric Conversion Characteristics of a Quadruple Parallel-Cavity Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator (4C–HR TENG). Processes. 2026; 14(2):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020341

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xinjun, Chaoming Huang, and Zhilin Wang. 2026. "Acoustic–Electric Conversion Characteristics of a Quadruple Parallel-Cavity Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator (4C–HR TENG)" Processes 14, no. 2: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020341

APA StyleLi, X., Huang, C., & Wang, Z. (2026). Acoustic–Electric Conversion Characteristics of a Quadruple Parallel-Cavity Helmholtz Resonator-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator (4C–HR TENG). Processes, 14(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020341