1. Introduction

Methyl oleate is a crucial chemical raw material, appearing as a colorless to pale yellow oily liquid. It exhibits diverse applications and is widely used in chemical engineering, pharmaceutical, food, and other industrial fields [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, methyl oleate can be further subjected to hydrodeoxygenation to produce second-generation biodiesel [

8,

9]. Traditionally, the synthesis of methyl oleate requires concentrated sulfuric acid or p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA) as catalysts. The former exhibits high corrosivity to equipment and poses difficulties in waste liquid treatment [

10], while the latter has a certain solubility in methyl oleate, leading to the generation of more waste liquid and still retaining moderate corrosivity. To address the issues of equipment corrosion and environmental pollution, various novel catalysts have been applied to the synthesis of methyl oleate in recent years, including ion exchange resins [

11,

12], zeolites [

13], heteropolyacids, [

14] metal oxide solid acids [

15], carbon-based solid acids [

16], ionic liquids [

17], deep eutectic solvents [

18], and lipases [

19]. Compared with other catalysts, lipase-catalyzed synthesis of methyl oleate offers distinct advantages, such as mild reaction conditions, low alcohol consumption, high selectivity, and no occurrence of side reactions like saponification [

20,

21].

Enzyme immobilization technology is a biological treatment technique that restricts free enzymes to a specific space or completely fixes them in a carrier matrix, thereby eliminating their free migration ability while maintaining continuous catalytic efficiency and enabling cyclic reuse [

22]. It addresses several critical technical issues of free lipases in industrial applications: for instance, enzyme molecules are prone to conformational changes under extreme pH, high temperature, or organic solvent environments, leading to activity loss; furthermore, free enzymes are difficult to separate and recover from the reaction system, resulting in poor reusability. The embedding method is an immobilization strategy that confines enzyme molecules within a three-dimensional space through grid-like gels or selectively permeable membrane materials. This method offers advantages such as efficient entrapment of enzyme molecules (immobilization efficiency > 90%) and realization of synergistic immobilization of multi-enzyme systems [

23]. In this study, sol–gel immobilized enzymes were prepared using the embedding method [

24,

25].

In this study, the reaction process of methyl oleate synthesis catalyzed by sol–gel immobilized enzyme was investigated in a batch reactor. The effects of catalyst particle diameter, initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol, temperature, and other conditions on the reaction were mainly examined, and the recycling performance of the catalyst was verified. The thermodynamic data of the reaction were obtained via the Van’t Hoff equation, while the kinetic parameters of the reaction were acquired using the pseudo-homogeneous (PH) model.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Materials

Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB, 6 wt %) was supplied by Novozymes, Bagsværd, Denmark. Tetramethoxysilane (TMOS, 98%), methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS, 98%) and polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400, 98%) were purchased from Aladdin Reagents (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Methanol (MeOH, 99.9%) and sodium fluoride (NaF, 98%) were obtained from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Anhydrous ethanol (AHE, 99.7%) was provided by Kaimate (Tianjin) Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Oleic acid (OA, 99%) was supplied by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China, and methyl oleate (MO, 98%) was purchased from Shanghai Haohong Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

Analytical balance (Model FA2004, Shanghai Sunyu Hengping Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), intelligent constant-temperature heating stirrer (Model DF-101S, Henan Yuhua Instrument Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China), low-temperature constant-temperature bath (Model DFY-5/20, Tianjin Kenuo Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), and high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC, Shimadzu LC-20A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS20, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta 450FEG, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), and ultraviolet spectrophotometer (not specified in original text, supplement: Model UV-2550, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) for enzyme activity determination.

2.3. Experimental Procedures

Solution A was prepared by weighing 0.54 g of tetramethoxysilane (TMOS), 1.934 g of methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS), and 3.39 g of methanol (MeOH). Solution B was prepared by weighing 0.014 g of polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG400), 0.49 g of 1 M sodium fluoride (NaF) solution, 1.26 g of deionized water, and 2.246 g of Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB). Both Solution A and Solution B were placed in a cold trap for 1 min. Subsequently, Solution A was poured into Solution B, and the mixture was stirred for 3 min to form a sol–gel solution. Finally, the solution was dried to obtain the sol–gel immobilized enzyme.

This study employs the hydrolysis reaction of p-nitrophenyl palmitate (p-NPP) for the determination of enzyme activity. The reaction equation is as follows:

The absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 410 nm using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer to determine the content of p-nitrophenol (p-NP) in the solution. Under the test conditions, one enzyme activity unit (U) was defined as the amount of CALB required to catalyze the hydrolysis of p-NPP to produce 1 μmol of p-NP per unit time. The enzyme activity per unit mass of the enzyme was denoted as specific activity (U/g).

The reaction was carried out in a solvent-free system using a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask. Oleic acid and methanol were weighed according to a specific molar ratio. A water bath was set to a certain temperature, the weighed raw materials were added, and the mechanical stirrer was adjusted to the corresponding rotation speed to ensure sufficient mixing of the reactants. Samples were taken every 30 min in the early stage of the reaction, and then every 1 h thereafter. The sample solution was diluted with anhydrous ethanol and sent for detection and analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.4. Sample Analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): A 0.1 mL aliquot of the reaction solution was taken and its mass was measured. The reaction solution was dissolved in 20 mL of anhydrous ethanol, and 4 μL of the diluted solution was injected into the HPLC system. A C18 chromatographic column (3.9 × 300 mm, 10 μm) was used, with the column temperature set at 36 °C. Methanol was employed as the mobile phase, the detection wavelength was 243 nm, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. The external standard method was adopted for quantification.

In this study, a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS20) was employed to characterize the types of functional groups in the samples. FT-IR testing distinguishes different chemical bonds based on their distinct vibrational-rotational energy levels within substances. Under the stimulation of infrared light, chemical bonds in the substances transition from the ground state to the excited state, and the functional groups in the samples are identified according to the characteristic absorption peaks at different wavenumbers. Potassium bromide (KBr) pellet method was used for sample preparation. The instrument had a resolution of 0.5 cm−1 and a testing range of 400–4000 cm−1.

The surface morphologies of the immobilized enzyme samples and microreactor coatings prepared in this study were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta 450FEG, FEI). During the test, the samples were first adhered to the surface of conductive tape and then subjected to gold sputtering treatment. The surface morphologies were observed in the secondary electron (SE) mode.

All experiments in this study were performed in triplicate, and the experimental data are presented as “mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD)”.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Evaluation of Sol–Gel Immobilized Enzymes

For enzyme-catalyzed functional components, the stability of enzyme catalytic activity is of great significance. In this chapter, the sol–gel method was adopted for the immobilization of

Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB).

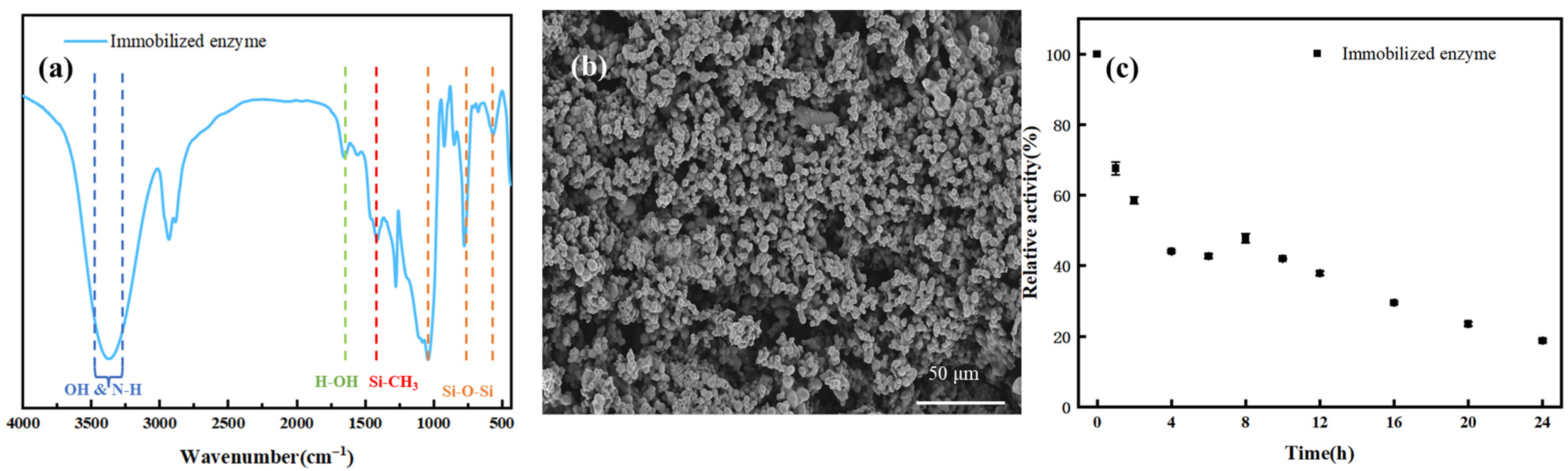

Figure 1a presents the FT-IR spectrum of the immobilized enzyme for functional group characterization. The characteristic peaks at 1037 cm

−1, 777 cm

−1, and 445 cm

−1 confirm the formation of the Si–O–Si network structure. To provide a hydrophobic microenvironment for CALB, methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS) was incorporated into the sol–gel precursors. The stretching vibration at 1277 cm

−1 verifies the presence of Si–CH

3 groups. The bending vibration at 1643 cm

−1 indicates the existence of residual bound water in the immobilized enzyme, corresponding to the residual silanol groups (Si–OH). The broad absorption band between 3500 cm

−1 and 3300 cm

−1 is attributed to the O–H and N–H stretching vibrations. In

Figure 1b, the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image illustrates the microstructure of the immobilized enzyme prepared by the sol–gel method. The dried gel exhibits a porous network structure, which provides channels for the binding of substrates to the active sites of the enzyme. When the incubation time at 333.15 K was 0, the activity of free enzyme for hydrolyzing p-NPP was 152.62 ± 8.46 mU, while the activity of sol–gel immobilized enzyme was 79.54 ± 3.64 mU.

In

Figure 1c, the normalized mean variance of the experimental data is 0.03, indicating a low degree of data dispersion. It can be observed that the activity of the immobilized enzyme gradually stabilized after 4 h of incubation. The main reasons for the decrease in enzyme activity during this stage are the partial denaturation of the enzyme at high temperature and the leaching of some loosely bound enzymes. Eventually, the immobilized enzyme maintained its activity in the buffer solution at 343.15 K for 8 h, with a relative activity of 47.9%. Notably, the relative activity values of the immobilized enzyme at 4, 6, and 8 h of incubation are closely clustered (47.9–62.5%), which can be attributed to two synergistic mechanisms: (1) The initial rapid activity loss within the first 4 h is mainly caused by the leaching of loosely bound enzyme molecules and partial denaturation of surface-exposed active sites. After 4 h, most loosely bound enzymes have been leached, and the remaining enzyme molecules are firmly entrapped in the sol–gel network, reducing further leaching. (2) The hydrophobic microenvironment provided by the Si-CH

3 groups in the sol–gel carrier (verified by FT-IR in

Figure 1a) mitigates the thermal denaturation of CALB. Meanwhile, the porous structure of the carrier (

Figure 1b) maintains the structural stability of the enzyme active center, leading to a slowed activity decay rate and thus clustered relative activity values in the 4–8 h period.

The first-order inactivation kinetic model was employed to describe the enzyme activity decay process. This model is applicable to most enzyme thermal inactivation reactions, with the expression as follows:

wherein, RA: Relative activity of the enzyme at incubation time t(%); RA

0: Initial relative activity (100%); k

d: Inactivation rate constant (h

−1), with smaller values indicating slower enzyme inactivation; t: Incubation time (h).

The half-life (t

1/

2) is defined as the time required for the enzyme activity to decrease to 50% of its initial value, derived from the above model:

Data fitting: Linear fitting was performed on the (t, ln(RA/RA

0)) data within 24 h, yielding the fitting equation:

By fitting the thermal stability data of the immobilized enzyme at 343.15 K using the first-order inactivation kinetic model, the inactivation rate constant (kd) was obtained as 0.058 h−1, thereby calculating a half-life of approximately 11.9 h.

3.2. Effect of Catalyst Particle Size and Stirring Rate on Methyl Oleate Esterification Rate

To obtain intrinsic kinetic data, the esterification rate of methyl oleate should be independent of both the diffusion within the catalyst pores and experimental conditions such as stirring speed. For heterogeneous solid–liquid catalytic systems, there are two types of diffusion limitations: internal diffusion and external diffusion. The former occurs inside the solid catalyst particles, while the latter takes place at the interface between the bulk liquid phase and the catalyst surface. The diameter of catalyst particles has a direct impact on internal diffusion; thus, varying the catalyst particle diameter is the most effective method to investigate the influence of internal diffusion. In this study, the effect of internal diffusion was examined through catalyst particle size screening.

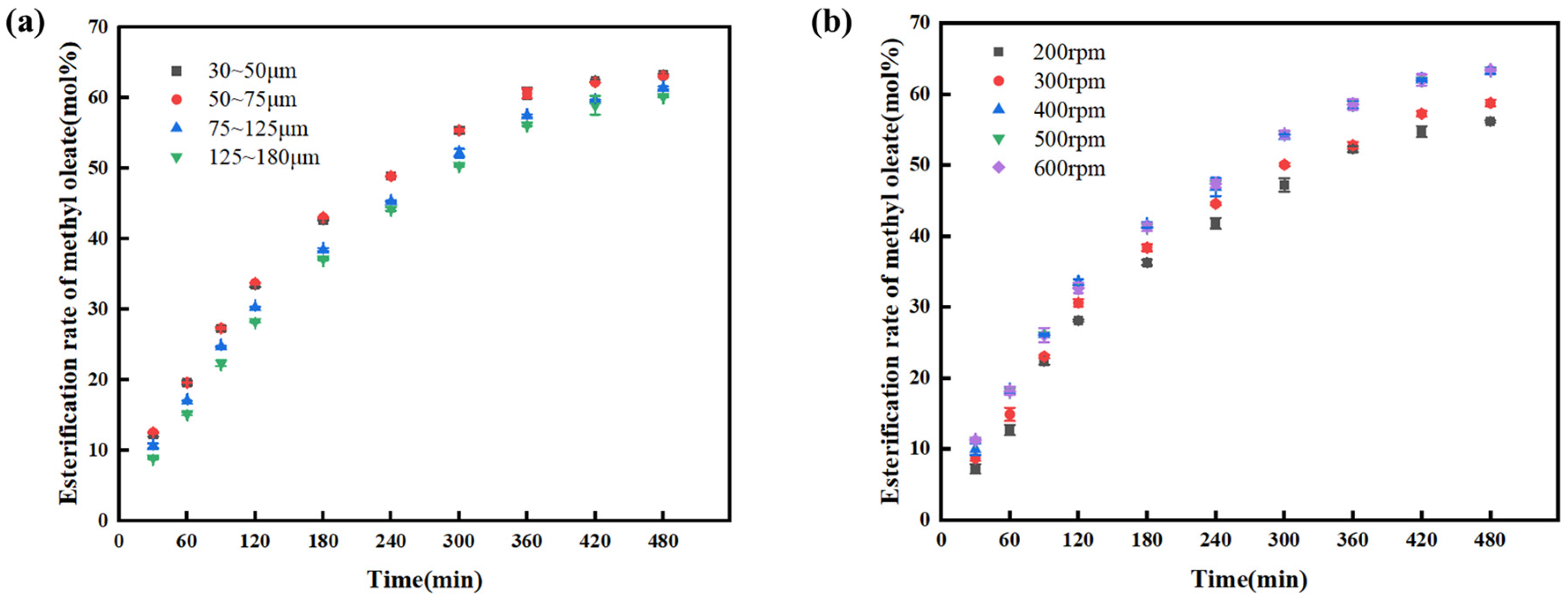

The effect of catalyst diameter on the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol was investigated under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 2a. When the catalyst diameter decreased from 125–180 μm to 50–75 μm, the esterification rate of methyl oleate increased gradually within the same time period. This is because the influence of internal diffusion was gradually weakened with the reduction in catalyst diameter. However, when the catalyst diameter was further decreased, there was no significant change in the esterification rate of methyl oleate—this is attributed to the elimination of internal diffusion when the catalyst diameter was in the range of 50–75 μm. The mechanical strength of the sol–gel carrier is positively correlated with its particle size. Particles with a size of 30–50 μm are finer, and during stirring (400 rpm), interparticle collisions and impeller shear forces will cause damage to the network structure of the carrier, resulting in particle fragmentation and pulverization. These fine particles are prone to suspension in the reaction system; during subsequent filtration and centrifugal separation, it is necessary to reduce the pore size of the filter medium or increase the centrifugal speed, which significantly increases the post-treatment cost, the catalyst diameter was set to 50–75 μm for subsequent experiments.

Equation (5) was used to determine whether the stirring rate met the condition of “just suspending” the catalyst, so as to ensure that there was no concentration gradient between the bulk liquid phase and the catalyst surface.

wherein, N

I is the impeller speed, s

−1; g is the gravitational acceleration, m/s

2; d

I is the impeller diameter, m; ρ

p is the catalyst density, kg/m

3; ρ

liq is the catalyst density, kg/m

3; d

p is the catalyst particle diameter, m; ε

s is the catalyst fraction in the slurry, g/g.

The maximum dosage of methanol was 6.408 g (200 mmol). Therefore, for 11.2984 g (40 mmol) of methanol, when the mass of the catalyst was 6% of the mass of oleic acid, the minimum density at 68 °C was 875 kg/m3, the catalyst fraction εs in the slurry was 0.0309, and the impeller diameter was 4.0 cm. In the sol–gel immobilized enzyme system, silica serves as the core framework component; herein, the solid density of silica (2200 kg/m3) was used as the catalyst density. The calculated minimum stirring speed required to ensure complete suspension of the catalyst (just-suspension speed) was approximately 6.83 s−1, i.e., 410 rpm. Thus, when the stirring speed exceeds 410 rpm, external diffusion can be considered eliminated. In addition to the theoretical criterion, the presence or absence of external diffusion can be directly verified through variable experiments.

The effect of stirring rate on the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol was investigated under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 2b. When the stirring rate increased from 200 rpm to 400 rpm, the esterification rate of methyl oleate increased within the same time period. However, when the stirring rate further increased to 500 rpm and 600 rpm, there was basically no change in the esterification rate of methyl oleate. This is because external diffusion in the system was eliminated when the stirring rate reached 400 rpm [

26]. In contrast, a higher stirring rate would intensify the abrasion between the impeller and the catalyst, which is unfavorable for the reusability of the catalyst. Therefore, the stirring rate was set to 400 rpm for subsequent experiments.

3.3. Effects of Oleic Acid-Methanol Molar Ratio, Catalyst Dosage, and Reaction Temperature on Methyl Oleate Esterification Rate

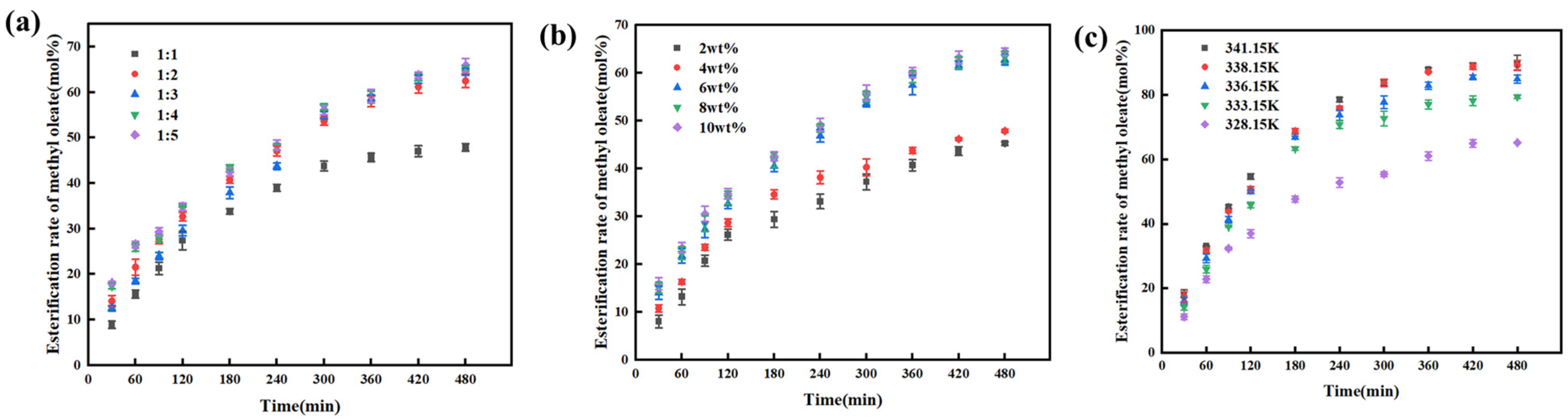

The effect of the initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol on the reaction was investigated under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 3a. When the initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol increased from 1:1 to 1:2, the esterification rate of methyl oleate increased. This is because the increased dosage of methanol enhances the collision frequency between reactant molecules, accelerating the reaction rate and thereby increasing the esterification rate. However, when the molar ratio further increased from 1:2 to 1:3, the esterification rate decreased instead. This is attributed to the fact that methanol also acts as a solvent and exhibits a certain concentration dilution effect, which reduces the concentration of oleic acid and consequently lowers the reaction rate. As a result, the conversion rate of methyl oleate exhibits a maximum value and a minimum value. With a further increase in methanol dosage, the esterification rate of methyl oleate is higher than that at the methanol-to-oleic acid molar ratio of 1:2. This is because the contribution of reaction driving force outweighs the dilution effect at this point. Despite the still low oleic acid concentration, the advantage of excess methanol concentration compensates for the insufficient collision frequency caused by dilution, promoting more oleic acid to convert into products. Thus, the esterification rate rises again and approaches the level observed at the molar ratio of 1:2. Considering the separation issue in post-treatment, an excessive amount of methanol would increase the difficulty of separation. Therefore, the initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol was set to 1:2 in this study.

The effect of catalyst dosage on the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol was investigated under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 3b. Within the same time period, the esterification rate of methyl oleate increased with the increase in catalyst dosage. This is because a higher catalyst dosage provides more active sites for the reaction, leading to a greater number of carbocations generated per unit time and thus a faster reaction rate [

27]. However, when the catalyst dosage increased from 6 wt% to 10 wt%, the improvement in the esterification rate of methyl oleate was not significant. Considering the catalyst utilization efficiency and cost factors, the catalyst dosage was set to 6 wt% in this study and subsequent experiments.

The effect of reaction temperature on the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol was investigated under the same conditions, as shown in

Figure 3c. As the reaction temperature increased from 328.15 K to 341.15 K, the reaction rate accelerated and the esterification rate of methyl oleate increased. However, when the temperature reached 338.15 K, further increasing the reaction temperature resulted in little difference in the esterification rate of methyl oleate—whether within the first two hours or at the equilibrium state. Moreover, the increase in temperature leads to higher energy consumption and potential issues with experimental safety. Therefore, selecting 338.15 K as the reaction temperature is deemed appropriate in this study [

28].

3.4. Reusability of the Catalyst

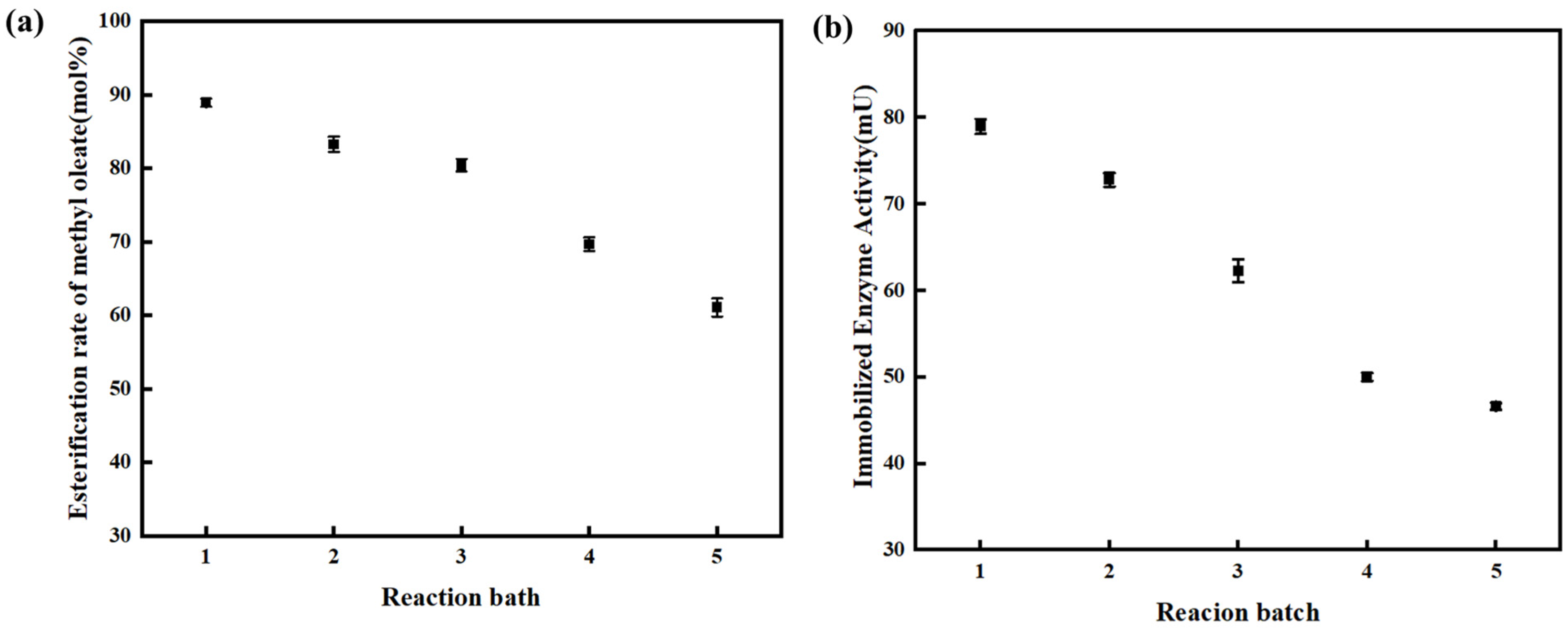

The reusability of the enzyme was investigated under the optimal experimental conditions (Catalyst diameter: 50–75 μm; Stirring rate: 400 rpm; Initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol: 1:2; Enzyme dosage: 6 wt%; Reaction temperature: 338.15 K). As shown in

Figure 4a, after 3 cycles of reuse, there was basically no change in the esterification rate of methyl oleate when the reaction reached equilibrium. However, when the enzyme was reused for the 4th cycle, the esterification rate of methyl oleate gradually decreased. This is because the enzyme detached from the carrier and water accumulated on the carrier surface, leading to a sharp decline in enzyme activity and consequently a decrease in the esterification rate of methyl oleate.

To provide supporting evidence for the enzyme deactivation mechanism, we tested the activity of the immobilized enzyme across multiple reaction batches, and the results are shown in

Figure 4b. As can be seen from the figure, the activity of the immobilized enzyme (unit: mU) shows a gradual downward trend with the increase in reaction batches. The decrease in activity is mainly attributed to the slight loss of enzyme molecules during the separation and recovery process of the immobilized enzyme.

3.5. Study on Chemical Equilibrium

The concentration of each component was measured over time at different temperatures until chemical equilibrium was reached. The calculation formula for the acid dissociation constant K

a of the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol is as follows:

In the equation, k

1 and k

2 are the rate constants for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively, with the unit of L/(mol·min); C represents the concentration of each substance at equilibrium, with the unit of mol/L. The relationship between the equilibrium constant K

a and temperature can be expressed by the Van’t Hoff equation:

In the equation, ΔH is the enthalpy change with the unit of kJ/mol; R is the gas constant, with a value of 8.314 J/(mol·K); and T is the reaction temperature, with the unit of K.

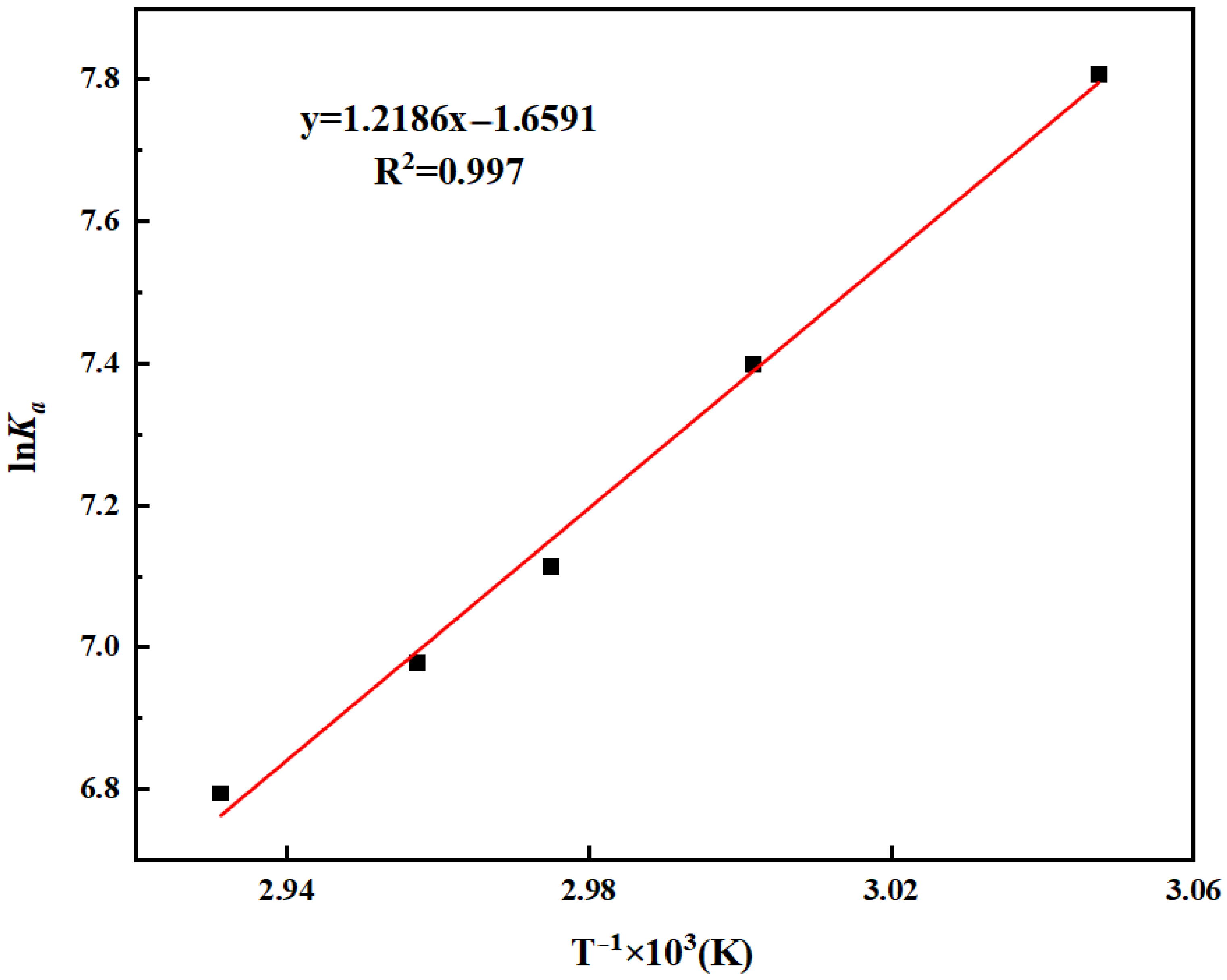

By fitting K

a and temperature T, Δ

rH

θ (standard molar enthalpy change in reaction) can be obtained. The fitting results are shown in Equation (8) and

Figure 5. The calculated enthalpy change is −10.13 kJ/mol, indicating that the esterification reaction between oleic acid and methanol is an exothermic reaction.

3.6. Kinetic Calculation

Mass transfer resistance exerts a significant influence on the reaction; therefore, the effects of internal and external diffusion must be eliminated prior to conducting the kinetic simulation. In this study, the influences of internal and external diffusion have been eliminated, as detailed in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2.

The esterification reaction is a second-order reaction, and this esterification reaction is specifically a reversible second-order reaction [

29]. In the entire reaction system, it can be simplified into the following two reactions:

Since the reactants and products of this reaction affect both the forward reaction rate and the reverse reaction rate, the esterification kinetics of oleic acid and methyl oleate is described using the pseudohomogeneous (PH) [

30,

31,

32] second-order kinetic model as follows:

In Equations (9)–(11), the forward reaction rate constant k

1 and the reverse reaction rate constant k

2 can be obtained using the Arrhenius equation.

In the equations, A

1 and A

2 are the pre-exponential factors for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively, with the unit of L/(mol·min); Ea

1 and Ea

2 are the activation energies for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively, with the unit of kJ/mol. Based on the kinetic model, the forward reaction rate constants at different temperatures were obtained by fitting the experimentally measured data points of each component’s concentration change over time using the nonlinear least squares method. Subsequently, the reverse reaction rate constants at each temperature were calculated using Equation (6), as shown in

Table 1.

The Arrhenius Equations (12) and (13) were linearized as follows:

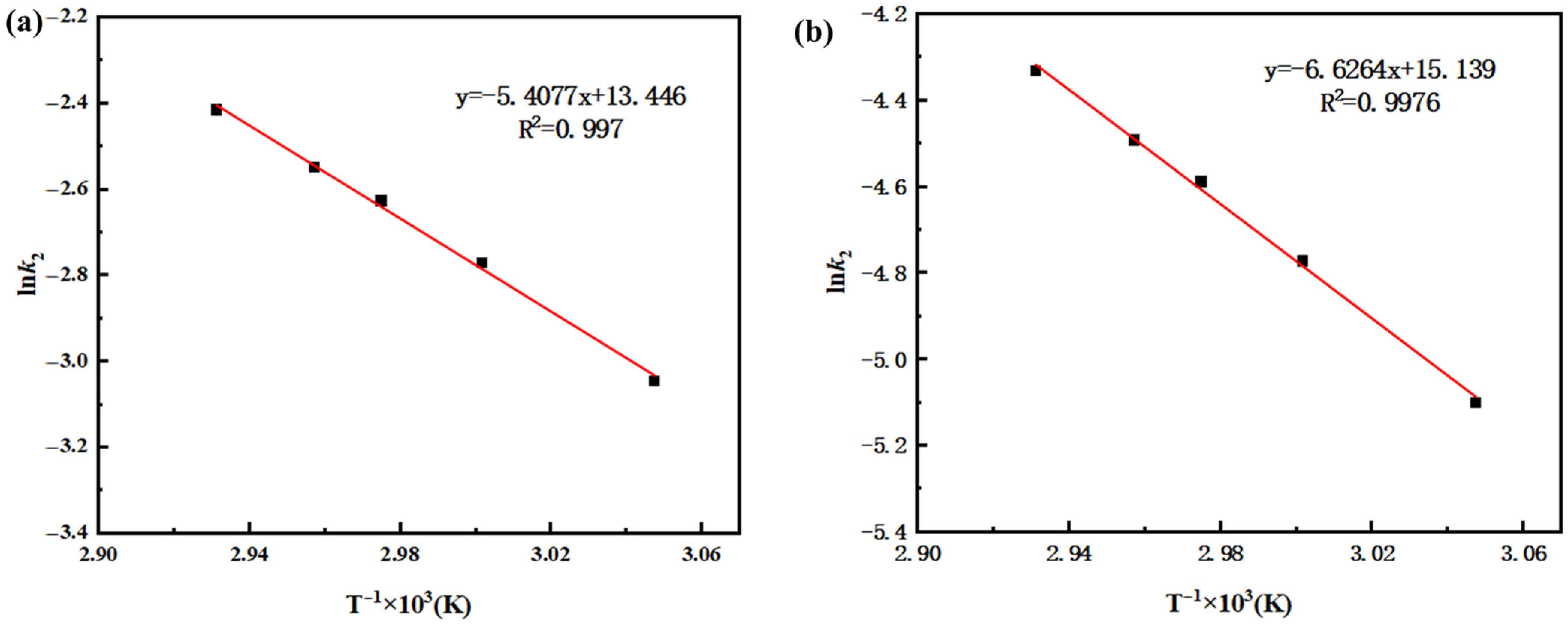

Plots of ln k versus 1/T were made for the forward and reverse reactions. As shown in

Figure 6a,b, the forward and reverse reaction rate constants exhibit a linear relationship with temperature, confirming the applicability of the Arrhenius equation. The value of −Ea./R can be obtained from the slope of the lines, and ln A from the intercepts, thereby allowing the calculation of the activation energies (Ea) and pre-exponential factors (A) for both the forward and reverse reactions. It can be seen from

Figure 6a,b that the fitting lines for the forward and reverse reactions have good correlation, with R

2 (coefficient of determination) greater than 0.99 in both cases. Based on the equations of the fitting lines, the activation energies Ea

1 and Ea

2 were calculated to be 44.96 kJ/mol and 55.09 kJ/mol, respectively, while the pre-exponential factors A

1 and A

2 were 472,125 L/(mol·min) and 187,025 L/(mol·min), respectively.

By substituting the kinetic parameters into Equation (11), the kinetic equation for the esterification of oleic acid with methanol to synthesize methyl oleate is obtained as follows:

Using the thermodynamic relationship between the equilibrium constant and Gibbs free energy:

Taking the standard temperature (298.15 K) as an example (the Ka value at this temperature was obtained by extrapolation using the fitted Van’t Hoff equation). The calculated standard molar Gibbs free energy change is −0.82 kJ/mol.

Based on the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation:

The calculated standard molar entropy change is −31.2 J/(mol·K).

4. Conclusions

In a batch reactor, the esterification reaction of oleic acid with methanol catalyzed by sol–gel immobilized enzyme was investigated. Through the optimization of experimental factors, the optimal reaction conditions were determined as follows: catalyst diameter of 50–75 μm, stirring rate of 400 rpm, initial molar ratio of oleic acid to methanol of 1:2, enzyme dosage of 6 wt%, and reaction temperature of 338.15 K. Under these conditions, the esterification rate of methyl oleate reached 90.01%. The Van’t Hoff equation was used to describe the relationship between the equilibrium constant and temperature, and the calculated enthalpy change (ΔH) was −10.13 kJ/mol. After eliminating the influence of internal and external diffusion on reaction mass transfer, a pseudohomogeneous second-order kinetic model was employed to simulate the kinetic process of the reaction between oleic acid and methanol. This result provides a reference for the scale-up of the reaction process.

The analytical method established in this study provides a universal approach for the process optimization of biocatalytic ester synthesis. Meanwhile, this research still has certain limitations: the long-term cyclic stability of the catalyst needs to be further improved, and future efforts can optimize the interaction between the enzyme and the carrier through carrier modification technology to enhance the long-term service performance of the catalyst. In subsequent studies, based on the kinetic parameters and thermodynamic data obtained in this work, experiments related to continuous-flow reactors are planned to verify the scalability of the reaction process, thereby providing more direct technical support for industrial production.